INDUS VALLEY CIVILIZATION

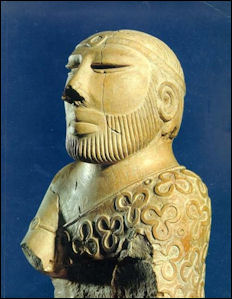

Mohenjo-daro Priest King The Indus Valley civilization is the oldest one known in Asia. Stretching from the Arabian Sea to the Himalayas and from the deserts of India to what is now Iran, it embraced 1,500 or so settlements and covered 280,000 square miles, an area roughly the size of Texas, or twice the size of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. [Source: Mike Edwards, National Geographic, June 2000; Santi Menon, Discover magazine, December 1998]

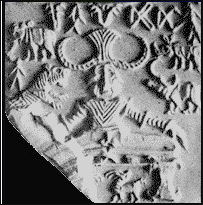

Also known as the Harappan civilization, a name derived from the Indus city of Harappa, the Indus Valley civilization is regarded as one of three early civilisations of the Old World along with Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. At its peak, the civilisation may have had a population of more than 5 million people, making up 10 per cent of the world's population. Among their settlements, researchers have uncovered the world's first known toilets, complex stone weights, drilled gemstone necklaces and exquisitely carved seal stone. Carved on these artefacts is an unusual and complex script, which researchers have still not deciphered.

The Indus Valley civilization was founded roughly around 3000 B.C. and flourished from 2600 to 1900 B.C. Regarded as the world’s oldest advanced civic culture, it is believed to have been a collection of states. Much about it is unknown because the civilization’s written language has not been deciphered and no other culture with written languages described them (there was no mention of them in the Bible or the Vedas, which date back to 1500 B.C.). What is known has been determined from archeological excavations.

The Indus Valley civilization was centered around Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro, two city-state civilizations that emerged around 3300 B.C. and endured until around 1500 B.C. Anthropologists regarded the Indus Valley cultures as one of the world's first civilizations along with Mesopotamia (founded in 3300 B.C), Egypt (founded in 3100 BC), and Yellow River Culture of northern China (founded shortly after 2000 BC). The Indus culture existed at the same time as these other cultures. Although trade existed between them. They appear to have developed independently and didn’t have much influence on one another.

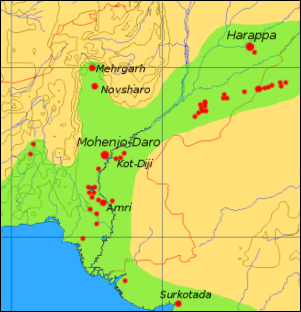

At least three major urban areas were located in the Indus River Valley:Mohenjo-Daro (also spelled Mohenjodaro), Harappa and Dholovira. The Indus Valley civilization was bound together by a common art and written language, and possibly by religion and trade as well. The Indus Valley civilization cities were linked by the Indus river. The Indus River flows south from Karakoram and Himalayan Mountains through present-day Kashmir and Pakistan to the Indian Ocean. In the north it flows along the Pakistan-India border. Although the Indus Valley civilization was scattered over a large area it was not large in terms of population. At its its height it was home to perhaps 400,000 people.

Book: Encyclopedia of Ancient Asian Cultures By Charles Higham

Extent of the Indus Valley Civilization

Besides Mohenjo-daro and Harappa, archaeological explorations reveal that there were a number of other sites in lower and upper Sind (Jhukhardaro, Canhu-daro), South Punjab and Baluchistan (Nal in Kelat State) belonging to the same Chalcolithic culture. Few traces of it have been found in the Gangetic valley, which in later times played an important part in the cultural and political history of India. Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa are now in Pakistan and the principal sites in India include Ropar in Punjab, Lothal in Gujarat and Kalibangan in Rajasthan. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

From the earliest times, the Indus River valley region has been both a transmitter of cultures and a receptacle of different ethnic, linguistic, and religious groups. Indus Valley civilization (known also as Harappan culture) appeared around 2500 B.C. along the Indus River valley in Punjab and Sindh. This civilization, which had a writing system, urban centers, and a diversified social and economic system, was discovered in the 1920s at its two most important sites: Mohenjo-daro, in Sindh near Sukkur, and Harappa, in Punjab south of Lahore. A number of other lesser sites stretching from the Himalayan foothills in Indian Punjab to Gujarat east of the Indus River and to Balochistan to the west have also been discovered and studied. How closely these places were connected to Mohenjo-daro and Harappa is not clearly known, but evidence indicates that there was some link and that the people inhabiting these places were probably related. [Source: Peter Blood, Library of Congress, 1994 *]

Andrew Lawler wrote in Archaeology: “ Over the past few decades, archaeologists working to answer some of these questions have identified several other major urban centers and hundreds of smaller towns and villages that have started to provide a fuller picture of the Indus civilization. It’s now clear that the Indus was not a monolithic state, but a power made up of distinct regions, and that it involved a much larger geographical area than imagined by the 1920s excavators. Covering some 625,000 square miles, the Indus surpassed Egypt and Mesopotamia in size, and may have included as many as a million people, a staggering figure for an agricultural society that depended on the unreliable waters of the Indus River and its tributaries. [Source: Andrew Lawler, Archaeology, January/ February 2013]

Early Indus History

Exactly when and where the Indus Valley civilization began and took root is still a matter of debate. Large and old settlements have been found in the Quetta, Loralai and the Zhob valleys in Baluchistan. Studies of these places seems to indicate that the people that lived in these places were semi-nomadic. The first permanent settlements are found closer to the flood plains of the great Indus River system.

Evidence of agriculture and urbanism dated to 7000 B.C.”older than Mesopotamia — -has been found at a site at Mehrgarth, an ancient settlement between the upland valleys of Baluchistan and the Indus flood plains. The settlement covered six hectares in 7000 B.C. and grew by 6000 B.C. to 12 hectares and had a population of maybe 3,000 people. The people that lived there raised wheat and barely and used domesticated cattle and water buffalo and hunted wild sheep, goats and deer. The dead were ritually buried, curled up on their sides, with some possessions, including turquoise beads from Turkmenistan,

The people of the Indus valley began trading on a wide scale at an early age. In the first known seafaring voyages, which may have taken place as early as 3500 B.C., Mesopotamians traveled across the Persian Gulf between Persia and India. See Indus and Mesopotamian Trade

Around 3500 B.C., permanent settlements began springing up over a wide area of the Indus River System. They are believed to have been settled by nomads that found advantages to living along rivers. The descendants of the Indus people were described in ancient Sanskrit texts as having dark skin. It is believed they spoke a Dravidian language. If this is true then the Indus Valley civilization is the ancestor the Dravidian civilization in southern India.

The earliest Indus settlements were strongly fortified neolithic villages destroyed by conquest. The people that lived here used copper and stamp seals and worshiped mother goddesses and horned deities. Archeologists date different groups and periods from this era based on different types of pottery. The fact that Indus Valley civilization settlements were built on the ruins of settlements of these cultures suggests that Indus Valley culture was imposed on them.

Kot Diji and Precursors of Indus Valley Urbanization

From the beginning of the 4th millennium B.C., the individuality of the early village cultures began to be replaced by a more homogenous style of existence. By the middle of the 3rd millennium, a uniform culture had developed at settlements spread across nearly 500,000 square miles, including parts of Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat, Baluchistan, Sind and the Makran coast. [Source: Indian government Ministry of External Affairs]

Early Indus Valley towns dated 4000–3000 B.C. were farming communities situated in different parts of Baluchistan and Lower Sind . The earliest fortified town to date is found at Rehman Dheri, dated 4000 B.C. in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa close to River Zhob Valley. Other fortified towns found to date are at Amri (3600–3300 B.C.) and Kot Diji in Sindh and at Kalibangan (3000 B.C.), India at the Hakra River.

Kot Diji — on the east bank of the Indus opposite Mohenjo-daro — was the home of a culture that produced well-made pottery and houses built of mud-bricks and stone foundations. Located about 24 kilometers south of Khairpur in the province of Sindh, Pakistan and occupied by 3300 B.C., it is it is considered a forerunner of the Indus Civilization.The Pakistan Department of Archaeology excavated at Kot Diji in 1955 and 1957. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Kot Diji site (3300–2600 B.C.) covers 2.6 hectares and is situated at the foot of the Rohri Hills where a fort (Kot Diji Fort) was built around 1790 by the Talpur dynasty ruler of Upper Sindh. The earliest occupation of this site is termed 'Kot Dijian', which is pre-Harappan, or early formative Harappan. At the earliest layer, Kot Diji I (2605 B.C.), copper and bronze were not used. The houses and fortifications were made from unbaked mud-bricks. Lithic material, such as leaf-shaped chert arrowheads, shows parallels with Mundigak layers II-IV. The pottery seems to anticipate Harappan Ware. Later, bronze was used, but only for personal ornaments. Also, use of the potters wheel was already in evidence.

The Early Harappan phase construction consists of two clearly defined areas. There is a citadel on high ground about 12 meters high, and outer area. The high ground area was for the elites. It was separated by a defensive wall with bastions at regular intervals. This area measures about 500 ft x 350 ft. The Outer area, or the city proper, consisted of houses of mud bricks on stone foundations.

Pottery found from this site has designs with horizontal and wavy lines, or loops and simple triangular patterns. Other objects found are pots, pans, storage jars, toy carts, balls, bangles, beads, terracotta figurines of mother goddess and animals, bronze arrowheads, and well-fashioned stone implements. A particularly interesting find at Kot Diji is a toy cart, which shows that the potter’s wheel permitted the use of wheels for bullock carts.

Glazed steatite beads were produced. There was a clear transition from the earlier Ravi pottery to what is commonly referred to as Kot Diji pottery. Red slip and black painted designs replaced polychrome decorations of the Ravi Phase. Then, there was a gradual transformation into what is commonly referred to as Harappa Phase pottery. Early Indus script may have appeared at Kot Diji on pottery and on a sealing. The use of inscribed seals and the standardization of weights may have occurred during the Kot Diji period. Late Kot-Diji type pots were found as far as Burzahom in Jammu and Kashmir.

There are obvious signs of extensive burns over the entire site, including both the lower habitation area and the high mound (the fortified town), which were also observed at other Early Harappan sites: Period III at Gumla, Period II at Amri, Period I at Naushero. Signs of cleavage were observed at Early Harappan phase Period I at Kalibangan. The cause of the disruptions and/or abandonment of these sites toward the end of the Early Harappan phase remains unexplained.

Indus Valley Civilisation May Be 2,500 Years Older than Thought

Some scholars argue that the Indus Civilization is around 8,000 years old based on pottery and animal bones carbon dated to that time found at Bhirrana, an Indus Valley site. Sarah Griffiths wrote in MailOnline:“A team of researchers from the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), Institute of Archaeology, Deccan College Pune, and IIT Kharagpur, have analysed pottery fragments and animal bones from the Bhirrana in the north of the country using carbon dating methods. ‘Based on radiocarbon ages from different trenches and levels the settlement at Bhirrana has been inferred to be the oldest (more than 9 ka BP) in the Indian sub-continent,’ the experts wrote in Nature’s Scientific Reports journal. [Source: Sarah Griffiths for MailOnline, June 2, 2016]

“They used also used ‘optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) method’ to check the dating and investigate whether the climate changed when the civilisation was thriving, to fill ‘a critical gap in information … [about] the Harappan [Indus Valley] civilisation.’ Anindya Sarkar, a professor at the department of geology and geophysics at IIT Kharagpur, told International Business Times: ‘Our study pushes back the antiquity to as old as 8th millennium before present and will have major implications to the evolution of human settlements in Indian sub-continent.’

Mohenjo-Daro

Mohenjo-Daro (350 miles from Karachi) was the center of an ancient Indus Valley civilization, and perhaps its capital. The largest of several wealthy cities in the Indus Valley, Mohenjo-Daro covered about one square mile, only a small potion of which has been excavated. A man-made, plateau-like hill, known as the citadel, was on one side of the city. About 300 structures have been excavated there.

Mohenjo-Daro means "Mound of the Dead." The plateau-like citadel is believed to be have been the place where the rulers of the kingdom lived. The common people lived in the flatlands. At its height Mohenjo-Daro was home to maybe 80,000 people.

Founded perhaps 6000 years ago, Mohenjo-Daro flourished between 2500 and 2000 B.C. along the irrigated banks of the Indus River when the climate wasn't as harsh as it is today. Only Egypt can lay claim to a civilization that was as old and as large.

Exposing bricks found at Mohenjo-Daro was halted in the 1960s because the bricks began to crumble when exposed to the air. The problem is that the bricks have been soaked in ground water, leaving behind salt. Exposure to the sun and air draws out the moisture, leaving behind the salt, causing the bricks to crumble.

See Separate Article MOHENJO-DARO factsanddetails.com

Harappa

Harappa (127 miles south of Lahore) was another large Indus city. It may have been a twin capital with Mohenjo-Daro. Named after a nearby town and 400 miles from its sister city, Mohenjo-Daro, it extended over an area of 1.25 square kilometers (400 acres) and was home to 20,000 or more people and probably controlled a New-York-size area covering about 50,000 square miles.

Harappa was located along the Rawa River, a tributary of the Indus, in a fertile flood plain. A reliable source of food helped the city take care of its own needs. Its location at the crossroads of important trade routes helped it prosper.

The Indus Valley civilization is sometimes called the Harappan civilization because the first evidence of the Indus culture was found there. Archeologists have found remains of a village dating back to 3300 B.C. at Harappa. Potsherds found there have symbols that are similar to the Indus script. By 2200 B.C. Harappa covered 370 acres and was home to about 80,000 people, making it roughly equivalent on side to Ur in Mesopotamia.

Harappa was discovered in 1921 and Mohenjo-daro was found a year later by Sir John Marshall. The sites have been continually excavated since then. British railroad workers scavenged large numbers of bricks from Harappa in the 1850s for ballast for their new tracks.

See Separate Article GREAT CITIES OF THE INDUS VALLEY CIVILIZATION factsanddetails.com

Dholovira

Dholovira (30 miles from the Pakistan border) is another 5000-year-old city in the desolate Rann area of Kutch in far western India that once stood on an island in a marsh, periodically flooded by the Arabian Sea.

Dholavira was occupied between 2900 and 1500 B.C. with evidence of decline around 2100 B.C. Around 2000 B.C. the site was abandoned and the reinhabited around 1500 B.C. Tokens, seals and figurines that have been unearthed that are like those found at Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa.

Scholars believe that Dholavira may have supplied salt to the Indus area and was once connected to the Arabian Sea by a channel or canal though no evidence of such a waterway has been found. Other large Indus settlements include Lurewala in the central Indus valley, Ganweriawala in the Cholistan desert and Kalibangan and Lothal in India. Some have suggested that this were independent city states. Other have argued they were provincial capitals under Harappa and Mohenjo-daro.

See Separate Article GREAT CITIES OF THE INDUS VALLEY CIVILIZATION factsanddetails.com

Mohenjodaro

Indus Government and Military

Explaining why a lack of grand temples and tombs was a good thing, Kenoyer told Discover, "When you take gold and put it in the ground, it’s bad for the economy. When you waste money on huge monuments instead of shipping, it's bad for the economy. The Indus Valley started out with a very different basis and made South Asia the center of economic interactions in the ancient world."

In may places in modern Pakistan a barter system is used rather than a cash economy. A pot maker might supply farmers for an entire year with pots, urns and cooking vessels. At harvest time he is paid with wheat, which he in turn sells to townspeople. Some scholars suggest a similar system was used in Harappa, which had no currency.

While ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia relied heavily on slaves and forced labor, the Indus Valley civilization appears to have relied more on craftsmen and trade. Standardized weights enabled traders to make fair trades. The weights may have been used by officials to levy taxes.

The Indus people of Mohenja-Daro and Harappan had a system of measurements. They smelted, cast and used copper and bronze. Harappa kilns produced millions of bricks. The Indus people used the wheel for transportation.

Indus pottery was mostly plain with a red slip and painted black decorations. It was not very good in quality and was mass produced. Potters produced vessels with similar designs. They fashioned bowls, pots, urns, cooking vessels and churns with a potter's wheel and packed 200 or so items at a time in kiln fired by animal dung. The vessels are left in the smoldering fire for about three days. Modern potter use the same technique. The Indus people are believed to have turned pottery wheels. No potters wheels have been found but archaeologists believed they were used based on how perfectly rounded their vessels were.

Jim Shaffer of Case Western Reserve told U.S. News and World Report, "In the absence of a political elite, or a standing army, one is left with the symbolic — -a system of beliefs.

Uniform weights found at Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro have been offered as evidence that government used standardized measurements to ensure fair trade and possibly to levy taxes. Some scholars have speculated the entire region may have been rules by one dynasty. See Indus City Gates, Taxes and Trade

No evidence of battles or military damage has been found in the cities. Skeletons show no evidence of violence. So few weapons have been found, some archeologist wonder whether the Indus cultures even had a military. No scenes of battles or prisoners or fighting, like this found in Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt, have been found in the Indus Valley. See City Walls

Indus Trade

Bullock cart with driver The Indus trade network stretched from India to Syria. The Indus people imported raw materials like lapis lazuli from Afghanistan; clam and conch shells from the Arabian Sea; timber from the Himalayas; silver, jade and gold from Central Asia; and tin, copper and green amozite, perhaps from Rajasthan or the Gujarat area of India. Evidence of maritime trade with Mesopotamia (about 1,500 miles form the Indus area) includes ivory, pearls, beads, timber and grain from the Indus area found in Mesopotamian tombs. Similarities between pottery in Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley is further evidence of trade between the two regions.

The presence of a standardized weight and measurement system shows that the trade system was sophisticated, extensive and organized. Certain towns became known for specialized crafts: for example, Lothal for carnelian beads; Balakot for bangles, and the Rohri Hills for flint blades and tools. Some large brick-making and pottery making factories were located in the Cholistan desert. At Shortugai in Afghanistan, the Harappans established a colony to mine lapis lazuli.

Products brought from Mesopotamia, Iran and Central Asia were traded for raw material and precious metals. Based on its location on trade routes, Kenoyer told Discover, Harappa "was a mercantile base for rapid growth and expansion...The way I envision it. If you had entrepreneurial go-get-'em, and you had a new recourse, you could make a million in Harappa." There are number of archeological sites near Karachi that were probably used as ports. See Indus City Gates

There is no so sign of great rulers, large palaces, grand monuments or elaborate tombs. Even so, some scholars believe Dholavivia required a strong ruler to coerce workers to do all the work that was done there.

Andrew Lawler wrote in Archaeology: “At many Indus sites, archaeologists have found mortars and pestles that University of Wisconsin researcher Randall Law determined were made of sandstone from southern Baluchistan to the west and steatite from northern Pakistan or Rajasthan to the east. Agate, a favorite stone for bead-making, was transported from Gujarat to the south. Lead, meanwhile, was brought from Baluchistan and silver from Rajasthan, both of which initially appear to have been prized primarily as makeup. In addition, Mohenjo-Daro was ideally placed to take advantage of the chert—a hard stone that can be used to make sharp blades—that litters the Rohri Hills and the Thar Desert just to the east and was traded all over the Indus region. Pakistani archaeologist Qasid Mallah has recently found hundreds of encampments and settlements that demonstrate that this was a thriving area at the height of the Indus civilization. And, according to New York University archaeologist Rita Wright, chert may have sparked the growth of Mohenjo-Daro as a center of that important network.”

Indus and Mesopotamian Trade

toy cart The Sumerians established trade links with cultures in Anatolia, Syria, Persia and the Indus Valley. Similarities between pottery in Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley indicate that trade probably occurred between the two regions. During the reign of the pharaoh Pepi I (2332 to 2283 B.C.) Egypt traded with Mesopotamian cities as far north as Ebla in Syria near the border of present-day Turkey.

One Mesopotamian text records a court case involving a “Meluhhan,” thought to be the Sumerian word for someone from the Indus, while another mentions a Meluhhan interpreter at a Mesopotamian court.” [Source: Andrew Lawler, Archaeology, January/ February 2013]

The Sumerians traded for gold and silver from Indus Valley, Egypt, Nubia and Turkey; ivory from Africa and the Indus Valley; agate, carnelian, wood from Iran; obsidian and copper from Turkey; diorite, silver and copper from Oman and coast of Arabian Sea; carved beads from the Indus valley; translucent stone from Oran and Turkmenistan; seashell from the Gulf of Oman. Raw blocks of lapis lazuli are thought to have been brought from Afghanistan by donkey and on foot. Tin may have come from as far away as Malaysia but most likely came from Turkey or Europe.

Many goods that traveled through the Persian Gulf went through the island of Bahrain. There was an early Bronze Age trade network between Mesopotamia, Dilmun (Bahrain), Elam (southwestern Iran), Bactria (Afghanistan) and the Indus Valley. Dillum was a city-state on the island of Bahrain thrived from around 3200 B.C. to 1200 B.C. and described in Sumerian literature as the city of the gods. Archeologists have found temples and settlements on Dillum, dated to 2200 B.C. The earliest settlements in the Persian Gulf date back to the 4th millennium B.C. The are usually associated with the Umm an-Nar culture, which was centered in the present-day United Arab Emirates. Little is known about them.

The ancient Magan culture thrived along the coasts of the Persian Gulf during the early Bronze Age (2500-2000 B.C.) in Oman and the United Arab Emirates. Ancient myths from Sumer refer to ships from Magan carrying valued woods, copper and diorite stone. Archeologists refers to people in Magan as the Barbar culture. Based on artifacts found at its archeological site it was involved in trade with Mesopotamia, Iran, Arabia, Afghanistan and the Indus Valley. Objects from the Indus Valley found at Magan sites in Oman include three-sided prism seals and Indus Valley pottery.

Sumerian texts, dated to 2300 B.C., describe Magan ships, with a cargo capacity of 20 tons, sailing up the Gulf of Oman and stopping at Dilum to stock up on fresh water before carrying on to Mesopotamia. The texts also said Magan was south of Sumer and Dillum, was visited by travelers from the Indus Valley, and had high mountains, where diorite, or gabbro, was quarried to use to make black statues.

Book: “Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus” edited by Joan Aruz and Romlad Wallenfels (Metropolitan Museum/ Yale University Press, 2003). It discusses art in Mesopotamia in its own right and as it relates to art in the Mediterranean region, ancient India and along the Silk Road. It has good sections on technologies such as sculpture production and metal making.

Indus Agriculture and Livestock

Agriculture was centered around the Indus and its tributaries, which recedes during the summer, leaving behind rich alluvial soil, which can be cultivated to produce a crop the following spring. The Indus people grew barley, two types of wheat, dates, field peas, cotton, sesamum and mustard. Rice husks have been were found at Lothal and Ragpur.

The existence of such big cities as Mohenjo-daro and Harappa clearly indicates that food must have been available in an ample measure. Perhaps the grains they cultivated were wheat and barley, specimens of which have been found there. It is uncertain whether the plough had replaced the hoe, or the latter was still in use. Scholars believe that in olden times Sind received copious rainfall, and this, as also the presence of a great river, must have made the problem of irrigation easy of solution. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

The Harappans did not attempt to develop irrigation to support agriculture. Instead, they relied on the annual monsoons, which allowed the accumulation of large agricultural surpluses — which, in turn, allowed the creation of cities. [Source: Thomas H. Maugh II, Los Angeles Times, May 28, 2012]

Today, the landscape surrounding Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa is dry and dusty and about the only thing growing there are tamarisk bushes and acacia. But in the time of the Indus Valley civilization there were irrigated fields that produced wheat, barley, peas and sesamum. One of the largest structures at Mohenjo-Daro, a 150 x 75 foot structure, is believed to have been a granary that stored crops from these fields during the winter time.

Archeologists have found bones of cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, water buffalo, hens, elephants and camels — -all of which are believed to be to have been domesticated — -at Indus sites. There were elephants in the Indus area. There is evidence they were hunted for ivory and possibly meat. They may have been domesticated for labor. People in Harappa yoked cattle to plows and carts.

Bones of bull, sheep, pig, buffalo, camel, and elephant have been recovered in old layers while those of the dog and horse, having been found near the surface, may belong to later times. The wild animals familiar to them were rhinoceros, bison, monkey, tiger, bear, hare, which are depicted on seals and copper-tablets. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

End of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro

Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro were abandoned between 1900 and 1700 B.C. Trade and writing stopped. The unicorn symbol and the weight system of measurements disappeared. Nobody is sure exactly why the Indus Valley civilization collapsed but most archeologist speculate it was due to climatic change, flooding, invasion and/or disease.

The Indus Valley civilization probably collapsed at least partly as the result of the changing course of channels of the Indus river, which may have flooded some areas and left others high and dry. This may have disrupted agriculture and trade and brought the entire economy to an untimely end.

Flooding is often mentioned as a cause. Archeologist Jonathan Mark Kenoyer of Wisconsin University told National Geographic, "I think the fluctuations of the Indus had a major impact on Mohenjo-Daro. It whipped back and forth across the plains, causing floods that destroyed the agricultural base of the city. Trade and the economy were disrupted." The same thing may have happened at Harappa. There is some evidence that earthquakes may have shifted the earth’s crust to effectively block the Indus, forcing it to overflow its banks and flood a wide area.

Collapse of the Indus Valley Civilization

The Indus Valley civilization collapsed for unknown reasons some time after 2000 B.C. The possible reasons for the decline of Harappan civilization have long troubled scholars. Invaders from central and western Asia are considered by some historians to have been the "destroyers" of Harappan cities, but this view is open to reinterpretation. More plausible explanations are recurrent floods caused by tectonic earth movement, soil salinity, and desertification.

Archaeologists once believed that civilization began in the subcontinent along the Indus River valley in what is now Pakistan. It is now known that this great civilization covered a much larger area, about as large as modern Europe (minus Russia), extending from northern Pakistan to the Arabian Sea and along the tributaries of the Indus River in western India and Pakistan. Excavated sites such as the cities of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro reveal a well-organized system of town planning based on a rectangular street grid. [Source: Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts, The Art of South, and Southeast Asia, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York]

Andrew Lawler wrote in Archaeology: “Wheeler suggested in the 1940s that several skeletons discovered in an alley were evidence of a massacre, what he claimed to be an invasion of Aryan peoples from the north and west, an event mentioned in later Indian texts. Other scholars believed that a massive Indus flood forced the city’s abandonment. Both of these theories are now out of favor. Archaeologists now think that the city’s decline was more gradual; though whether economic dislocation or political turmoil was the main cause remains uncertain. Climate change may also have been a culprit, but scientists are at odds over whether the region suffered from a drought that might have led Indus urban dwellers to flee to the countryside. [Source: Andrew Lawler, Archaeology, January/ February 2013]

Indus Cities and Aryan Conquest

It was originally thought that Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa and other Indus settlements were conquered by Aryans. The Aryan invasion theory is based on 30 skeletons,, including women and children, found in later period Mohenjo-Daro ruins and descriptions of a "massacre" in the Rig-Veda, the collection of ancient Hindu hymns. The theory goes that the decline of Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa made them vulnerable to an invasion of Aryan "barbarian tribes" from Persia and Afghanistan. Indus technology was far superior to that of Aryans in every way except weapons technology.

Many scholars dismiss this theory because no weapons or evidence of an attack have been found. The skeleton could easily of come from people who died of disease. Moreover dating technology seems to indicate that the city fell into decline long before the Aryans arrived.

In any case as Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro declined, the Aryans "occupied the best land, cleared the forests, built permanent villages, and found a series of petty kingdoms in which they set themselves up as rulers over the region's indigenous inhabitants" (perhaps the source of the Brahma high caste). In some cases, new settlers dismantled Indus buildings and uses the materials to build new buildings.

Climate Change and the End of Indus Valley Civilization

According to PBS: “Climate change is emerging as a primary reason for its gradual demise. Geological evidence shows that the region's climate grew colder and drier, in part perhaps because of a weakened monsoon. By 1800 B.C., the Ghaggar-Hakra River, a river in the region that paralleled the Indus system and that some scholars suggest is the Saraswati, the lost sacred river of Rig Veda, was severely diminished. As a result, cities were abandoned and though some of the population remained, many migrated to more fertile lands in the east around the Ganges and Jumna River. [Source: PBS, The Story of India, pbs.org/thestoryofindia]

The team of researchers from the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), Institute of Archaeology, Deccan College Pune, and IIT Kharagpur wrote in Nature’s Scientific Reports journal: “‘Our study suggests that the climate was probably not the cause of Harappan decline.” While the ancient people relied upon heavy and regular monsoons between 9,000 and 7,000 years ago to water their crops, after this period, evidence at Bhirrana shows people continued to survive despite changing weather patterns. [Source: Sarah Griffiths for MailOnline, June 2, 2016]

“‘Increasing evidences suggest that these people shifted their crop patterns from the large-grained cereals like wheat and barley during the early part of intensified monsoon to drought-resistant species of small millets and rice in the later part of declining monsoon and thereby changed their subsistence strategy.” However, changing the crops they grew and harvested resulted in the ‘de-urbanisation’ of cities and no need for large food storage facilities. Instead, the people swapped to personal storage spaces to look after their families. ‘Because these later crops generally have much lower yield, the organised large storage system of mature Harappan period was abandoned giving rise to smaller more individual household based crop processing and storage system and could act as catalyst for the de-urbanisation of the Harappan civilization rather than an abrupt collapse.”

Migration of Monsoons Created, Then Killed Indus Valley Civilization?

A study co-authored by Dorian Fuller, an archaeologist with University College London, published in 2012 suggests the decline in monsoon rains led to weakened river dynamics, and played a critical role both in the development and the collapse of the Indus culture. The study set out to resolve a long-standing debate over the source and fate of the Sarasvati, the sacred river of Hindu mythology. Over five years an international team combined satellite photos and topographic data to make digital maps of landforms constructed by the Indus and neighbouring rivers. They then probed in the field by drilling, coring, and even manually-dug trenches and samples were tested. [Source: Sarah Griffiths for MailOnline, June 2, 2016]

Thomas H. Maugh II wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “The slow eastward migration of monsoons across the Asian continent initially supported the formation of the Harappan civilization in the Indus valley by allowing production of large agricultural surpluses, then decimated the civilization as water supplies for farming dried up, researchers reported. The results provide the first good explanation for why the Indus valley flourished for two millennia, sprouting large cities and then dwindled away to small villages and isolated farms.[Source: Thomas H. Maugh II, Los Angeles Times, May 28, 2012]

The Harappans did not attempt to develop irrigation to support agriculture. Instead, they relied on the annual monsoons, which allowed the accumulation of large agricultural surpluses — which, in turn, allowed the creation of cities. The new research was performed by a team led by geologist Liviu Giosan of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Woods Hole, Mass., and published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. Working in Pakistan, they used photographs taken by shuttle astronauts and images from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission to prepare maps of land forms in the region, then verified them on the ground using drilling, coring and manually dug trenches.

“Before the region was settled, regular and powerful monsoons flooded the Indus River and its tributaries, moving large amounts of sediment across the plains and cutting deep valleys through the deposits. One of the most striking features the researchers found was a mounded plain, 10 to 20 yards high, more than 60 miles wide and running almost 600 miles along the Indus. The rich silt deposited by the river was perfect for agriculture, the team said.

“By about 5,500 years ago, however, the monsoon area had drifted eastward and the devastating floods along the Indus were replaced by overflows that watered the soil and encouraged agriculture. "The Harappans were an enterprising people taking advantage of a window of opportunity — a kind of 'Goldilocks civilization,'" Giosan said. "As monsoon drying subdued devastating floods, the land nearby the rivers — still fed with water and rich silt — was just right for agriculture."

“But as the monsoons continued their eastward drift, the annual floods became weaker and less regular and the Harappan agriculture could no longer support the large cities. Beginning around 3,900 years ago, communities of farmers followed the monsoons to the East, forming small villages along the river that relied on the local rains. Those rains did not support a large agricultural surplus, Giosan said. The cities died out, the writing was lost, trade halted and the Harappan civilization was no more.

“The team also believes that they have solved another mystery, the fate of the mythical river the Sarasvati. The ancient Indian scriptures called the Veda described the Sarasvati as "surpassing in might and majesty all other waters" and "pure in her course from the mountains to the ocean." Those writings suggest that the Sarasvati was fed by Himalayan glaciers and flowed to the ocean. But the new data indicatethat there was no river during the period fed by glaciers, only those fed by the annual monsoons. If, indeed, there was a Sarasvati, it was a monsoonal river just like the others.”

DNA Study Debunks Aryan Invasion Theory

A study published in September 2019 claimed that Indus Valley people (Harappans) and Vedic people are same, which appears to debunk the Aryan Invasion Theory. Pratul Sharma wrote in The Week: “In a major finding that could impact the understanding of Indian ancestry, the DNA study of a 4500-year-old skeleton found in Rakhigarhi, in Haryana, suggests that modern people in India are likely to have descended from the same population.” This finding “came to light after scientists were able to sequence genome from the skeleton of a woman and study the archaeological evidence found in Rakhigarhi, a village located some 150 kilometers from Delhi. Rakhigarhi is the largest Harappan site in India. [Source: Pratul Sharma, The Week, September 6, 2019]

“The ancient-DNA results completely reject the theory of steppe pastoral or ancient Iranian farmers as source of ancestry to the Harappan population. This research also demolishes the hypothesis about mass human migration during the Harappan time from outside South Asia,” Prof Vasant Shinde, director of the Rakhigarhi project, said.

Shinde said the new breakthrough completely sets aside the Aryan migration or invasion theory. “The skeletal remains found in the upper part of the citadel area of Mohenjodaro belonged to those who died due to floods and not (of those) massacred by the Aryans as hypothesised by Sir Mortimer Wheeler. The Aryan invasion theory is based on very flimsy ground,” Shinde said, adding that the history being taught to us in text books should now be changed.

The DNA revealed that there was no migration or inclusion of any Iran or Central Asian gene into Harappan people. "There is a continuity till the modern times. We are descendants of the Harappans. Even the Vedic culture and (that of) Harappans are same,” Shinde said.

“This research, for the first time, has established the fact that people of Harappan civilisation are the ancestors of most population of South Asia. For the first time, the research indicates movement of people from east to west. The Harappan people's presence is evident at sites like Gonur in Turkmenistan and Shahr-i-Sokhta in Iran. As the Harappans traded with Mesopotamia, Egypt, Persian Gulf and all over South Asia, there are bound to be movements of people resulting into mixed genetic history,” he added.

These revelations assume political significance as there have been demands to rewrite the history books to say that Vedic people were the original inhabitants of the country and they did not come from Central Asia. “Our premise that the Harappans were Vedic people thus received strong corroborative scientific evidence based on ancient DNA studies,” he added.

Another significant claim in the study published in the scientific journal Cell, titled "An Ancient Harappan Genome Lacks Ancestry from Steppe Pastoralists or Iranian Farmers”, is that farming was not brought to South Asia by large-scale movement of people from the Fertile Crescent where farming first arose. Instead, farming started in South Asia by local hunter-gatherers.

As the study results were published, separate statements were issued by Harvard Medical School which had collaborated in the study. "Even though there has been success with studies of ancient-DNA from many other places, the difficult preservation conditions mean that studies in South Asia have been a challenge," says senior author David Reich, a geneticist at Harvard Medical School, the Broad Institute, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

In this study, Reich, along with post-doctoral scientist Vagheesh Narasimhan and Niraj Rai, who established a new ancient-DNA laboratory at the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences in Lucknow, led the preparation of the samples. They screened 61 skeletal samples from a site in Rakhigarhi, the largest city of the Indus valley Civilisation. A single sample showed promise: it contained a very small amount of authentic ancient DNA. The team made over 100 attempts to sequence the sample. Reich says: "While each of the individual data sets did not produce enough DNA, pooling them resulted in sufficient genetic data to learn about population history."

"Ancestry like that in the Indus Valley Civilisation individuals is the primary ancestry source in South Asia today," says Reich. "This finding ties people in South Asia today directly to the Indus Valley Civilisation." The authors of the study, however, have a word of caution. “Analyzing the genome of only one individual limits the conclusions that can be drawn about the entire population of the Indus Valley Civilization.”

After the Indus Valley Civilization

After its disappearance around 1500 B.C. there was a bewildering variety of princely states and kingdoms, small and large, throughout the subcontinent, creating a long history of war and conquest that was punctuated by foreign invasions and the birth of some of the world's largest religions: Buddhism, Jainism, Hinduism, and Sikhism.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Ministry of Tourism, Government of India, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2020