ECONOMIC HISTORY AFTER DENG XIAOPING

Market in Shandong Chinese President Jiang Zemin, a former mayor of Shanghai, played a major role in switching the focal point of China’s economic growth from southern China to the Shanghai area and the Yangtze River Valley.

In a speech that was intended to show his independence Jiang blamed Deng's market reforms for a "crisis of morality" that "engendered social chaos and economic imbalance." Jiang said that what China needed was a dose of "good medicine" — Confucianism. Some of these ideas were not readily welcomed. A popular that circulated around the time of Deng's death went: "Under Mao we go to the countryside/ Under Deng we go into business/ Under Jiang we go out of business.”

Describing China during the early Jiang years, Journalist and China expert James McGregor wrote in the Washington Post, “China is simultaneously experiencing the raw capitalism of the robber baron era of the late 1800s; the speculative financial mania of the 1920s; the rural-to-urban migrations of the 1930s; the emergence of the first-car, first-home, first fashionable-clothes, first college-education, first-family-vacation, middle class consumer boom of the 1050s; and even aspects of the social upheaval similar to the 1960s.”

In the mid-1990s the Chinese economy became overheated. Local official were jailed for approving large projects without central government approval. Price controls were introduced. And thousands of workers were mobilized for emergency projects.

Articles on ECONOMIC HISTORY AND CUSTOMS factsanddetails.com ; Articles on ECONOMICS factsanddetails.com ; HISTORY AFTER MAO factsanddetails.com

Zhu Rongji’s Economic Policies

Zhu Rongji — the Prime Minister of China during the later years of Jiang’s rule — is regarded as the architect of the economic policies that ushered in China’s second wave of growth. He broke down trade barriers, cut runaway inflation, rescued China from the Asian economic crisis in 1997, sold off state enterprises, broke up monopolies, ended state planning, introduced competition and deregulation,. streamlined the bureaucracy and secured China’s membership to the World Trade Organization.

Zhu's tough minded policies included driving the military out of many of its commercial enterprises, reducing the number of easy loans and credits to money-losing state-owned enterprises, introducing a value added tax and diverting tax revenues to the central government. To create jobs he launched a Keynesian public works program.

Zhu goal was to make China a developed country by 2050. Under Zhu. the government continued to run up huge deficits and accumulate bad loans but at same time attracted lots of foreign investment. In 1998, Zhu announced a plan to cut 30 million of the 100 million state workers. These goals were largely met.

Reforming State Enterprises, Privatization and Encouraging Entrepreneurial Spirit

In 1993 the Communist Party announced a "broad program to restructure, sell off or declare the bankruptcy of thousands of state-owned industries whose heavy losses and inefficiency threatened the country's economic expansion. The effort was slowed by fears of worker unrest, the absence of social safety net for the unemployed and a debate within the leadership of the Communist party over how much control the Communist Party should cede over the means of production.

Reforms include forcing business to raise funds from stock and bond issues instead of government handouts and giving shares in enterprises to their workers, and allowing unprofitable companies to go out of business. Between 1989 and 2001, the economic input of state-owned industries shrunk from two thirds to 28 percent.

China privatized tens of thousands of state-owned companies. The effort began in the early 1990s and accelerated in the late 1990s when President Jiang Zemin endorsed the sale of all but the largest state-owned companies. Under the slogan “Grasp the Large, Release the Small” the number of state enterprises fell from 262,000 to 159,000 in 2002. In 2003, the privatization drive was accelerated further when some large state-owned enterprises were put on the block and foreign and private investors were allowed to buy majority stake in them.

Privatization was seen as a way of making the economy more efficient and raising money for social programs. But the process was marred by corruption, insider deals and ruthless selling off assets and laying off workers. Many of the best companies were sold off to well-connected insiders in sweetheart deals. A common strategy among those that emerged very rich was to push the limits of what was acceptable and possibly go beyond it and then ask forgiveness An executive of the Chery car company told The New Yorker, “If you apply in the traditional manner you’ll end up waiting for years. During that time, the opportunity may very well pass you by.”

The government encourages entrepreneurial spirit as way to find jobs for people laid off from state jobs. Tens of thousands of new private and quasi-private enterprises were set up. Many of those who are chasing in on the market economy are street peddlers. Describing what reforms have meant to him, one man told the Washington Post, "It's not like the party” has “done anything for us. It's just that they stopped blocking us." Those who remain loyal two their Marxist values get left behind.

Asia Crisis in 1998 and China

China’s economy shrunk slightly in the early 1990s as a result of the slowing of growth. The effects were relatively minor because the growing economy was still in infancy. If the same thing were to happen with the economy the size it is the consequences could be dire on a global level.

As China was trying to seriously reform the economy, the Asian financial crisis hit. Unemployment rose and Standard and Poor downgraded the long-tern outlook for China. But over all, China emerged from the Asian financial crisis relatively unscathed partly because their currency was not convertible. Beijing didn't devalue the yuan and pegged it against the dollar. For a while black market currency dealers were trading yuan for dollars at 10 percent above the official rate.

China was able to maintain growth rates of 7 to 8 percent during the Asian financial crisis with help from massive infrastructure projects. It was largely resilient to the global slump that took place after the September 11th and the crash of the Internet stocks in the early 2000s and for the most part was able to maintain its high growth rate.

In 1998 China injected $500 billion into its faltering banking sector. In August 1998 when the Hong Kong stock market crashed, the Chinese government intervened by spending $15.1 billion to buy about 7.3 percent of the companies on the blue-chip Han Seng Index. The move fulfilled its intended result, restoring stability to the market. The efforts is seen s a model for the massive bail out of banks in the United States in 2008 except on a much smaller scale.

China recorded growth of 7.3 percent in 2001 despite September 11th, and 8 percent in 2002 and 8.3 percent in 2003, despite the SARS scare, Growth was spurred on by booming exports, continued flow of foreign investment and vigorous domestic consumption

Economic Worries in China

Analysts cited a high investment to GDP ratio as a sign that the economy was overheating. The amount of money floating around encouraged speculation on stocks, money markets and real estate. The real estate markets in Beijing, Shanghai and other places became highly inflated. There were worries that a bubble could burst and the economy could collapse.

Construction and infrastructure projects such as ports, power plants, bridges and subways and investment for such projects was one of the primary reasons for the high growth figures. But the projects were often financed with unrealistically cheap capital and often resulted in unrealistically high capacity. China has relied heavily on the such to produce growth. They make 45 percent fo GDP, compared to 15 percent n the United States and 30 percent in South Korea and Japan. In the 1990s such investments generated 50 cents of growth for very dollar invested bit the 2000s they generated only 20 cents for every one dollar invested.

See Bad Loans, Banks, Business and Trade

The government propped up bankrupt state-run enterprises to prevent unemployment and unrest. It kept money away from the private sector that could use the money more efficiently. Regional authorities approved all kinds of projects, often without Beijing’s approval to keep the economy humming. Expansion, sparked a surge in commodity prices leading to power shortages and transportation bottlenecks.

Capital flight became a problem. Much of the money made by corrupt officials and businessmen with foreign passports gas been squirreled out of the country. By some estimates amount of money flowing out China through capital flight has exceeded the amount of money coming in through foreign investment.

Nike factory in China

The stock markets performed poorly in the early and mid 2000s. The Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets were among the worst performers in and 2004 and 2005 amidst corruption scandals, brokerage firm collapses and incomplete disclosures. The Shanghai stock exchange composite index dropped from 2,218.03 in June 2001 to below 1000 in 2005 while the economy was growing at a break neck pace. The combined capitalization of the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets was less than Toyota, a indication that the markets were not taken seriously by serious investors.

There was a problem with overproduction and too much capacity in the early and mid 2000s raising concerns about deflation. The was some deflation as a glut of televisions, clothes, home appliances and other products caused prices of these items to drop.

Changes and Reforms in the Chinese Economy

In the early 2000s, there were signs that the economic growth might be slowing. Factories have been reporting heavy competition and overproduction, which have caused prices — and in turn wages — to fall. Inflation was hovering around 5 and 6 percent , which was raising concerns. Still growth continued at around 9 percent.

In 2002 entrepreneurs were encouraged to joining the Communist Party. As labor costs and other expenses rose because of wage increases and regulations resulting from environmental and labor concerns and obligation resulting from membership to the WTO many factory owners are taking their businesses to Vietnam or elsewhere.

To stimulate growth, Beijing launched a multi-billion-dollar, Keynsian-style infrastructure building and spending program, including large expenditures for public works projects, issued billions of dollars of bonds, stimulated investments on real estate, automobile manufacturing and power generation. Beijing also took measures to encourage consumer spending.

Disparity of income was seen as a major problem (See Hu Jintao). The five year plan approved in October 2005 was aimed at helping the rural poor and reducing the income gap between the rural poor and the wealthy and spreading economic growth to the interior. Other goal included cutting wasteful government spending, keeping the economy from overheating, restructuring the banking system and reforming the stock market. See Rural Poor.

Reforms launched in early 2006 included the abolition a farm tax that had existed for 2,000 years, doubling the low limit to which income tax kicks in and launching a system of market makers for currency trading and asset-backed and mortgage-backed securities.

Efforts to Cool the Chinese Economy

As 9, 10 and 11 percent growth rates continued year after year concerns arose over the economy overheating In the mid 2000s, Beijing began taking measures to slow economic growth, in part because of fears that depleting energy supplies, inflation, overproduction and real estate and stock market speculation was creating an economic bubble. There are worries the bubble could burst as it did in Japan in the early 1990s and as it did in South Korea and Southeast Asia in th the late 1990s.

Cooling measures have included: 1) raising interest rates; 2) raising the proportion of deposits that banks must hold in reserve; 3) cracking down on wasteful investments by naming and shaming officials that failed to tighten up planning procedures and observe environmental protection criteria; 4) strictly enforcing land use regulations; 5) denying loans from state-owned banks to projects that have not been approved the central government; 6) jailing bank officials who gave out unapproved loans; 7) curbing investments is sectors such as steel and property; and 7) requiring banks to boost their reserves to prevent them wastefully lending out money.

In December 2003, the government announced it was reducing spending on factories and construction and reducing loans to major industries and companies. Spending was increased on infrastructure to help reduce bottlenecks and power shortages. In October 2004, China’s central bank raised interest rates for the first time in nine years — from 5.3 percent to 5.7 percent — in an effort to slow down the economy. The rates were raised again twice in 2006 to 6.12 percent

In 2006, three provincial officials were punished for ignoring calls to slow investment. The officials had approved expensive coal-burning power plants without approval from Beijing. Six workers were killed when part of the plant collapsed as local authorities rushed to finish the plants despite orders to the contrary from Beijing. Their punishment was writing a self criticism.

The goal was to get growth down to 7 percent. Those goals were not met (See Growth Above). The government however was given credit for keeping inflation under control maintain a as growth continued at its blistering rate. Some economists worried that slowing the economy too much might raise unemployment and create social unrest. But if growth occurs too fast China’s could experience an economic collapse — a so-called hard landing — China’s economic is so biog and intertwined with the global economic it would not only cause a crisis in China but create a crisis that would have reverberations throughout the world.

Revaluation of the Yuan

In 2005, China revalued the yuan by 2.1 percent against the U.S. dollar, abandoning the peg against the dollar, and allowing the yuan to float against other currencies such as the yen, dollar and euro, and allowing it to float within 0.3 percent of the dollar a day using “baskets” of foreign currency — a technique mastered by Singapore.

The reevaluation had been anticipated for a long time. It was the first revaluation in 10 years. The adjustment was minor but was regarded as a first step because the yuan was still considered way overvalued. Many regarded the move as more political — to appease critics that had demanded a yuan devaluation — than economic.

The revaluation of the yuan changed the value of the yuan from 8.277 yuan to the dollar to 8.110 yuan to the dollar. The United States had been calling for a revaluation of 10 percent and been threatening to slap a 27.5 percent tax on Chinese imports.

The move was widely received positively around the world. Stock markets around the globe rose. Inventors welcomed the news as a sign of things to come more than on changes brought about the revaluation itself, which were modest.

The impact of the revaluation on the United States was minimal. Prices on Chinese goods were not expected to rise high enough to deter shoppers of do anything the United States’s trade deficit. Analyst said that a revaluation of around 10 percent would be necessary for there to be really significant changes.

A World Bank study has estimate that the value of the yuan will be 5.8 to the dollar in 2010 and 2.8 to the dollar in 2020. As the value of the yuan strengthens Chinese-made gods will be more expensive, Chinese labor costs will be higher and profit margins for foreign companies with facilities in China could shrink. At the same time foreign products will be cheaper in China and there will be more incentive for Chinese to buy them. If costs in China become too high, foreign investors might invest their money in other places were labor is cheap and costs are low.

Responding toe criticism of China’s slow pace of reform and failure to change the value of the yuan, one Chinese official, a deputy governor the Bank of China, at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, told his critics to back off and “clean you own houses first.”

After the Revaluation of the Yuan

The yuan appreciated steadily against the dollar. In the first year after the re-evaluation it had not risen more than 0.15 percent on one day, half the maximum of 0.3 percent, and gained 0.9 after one year. The value of the yuan broke the 8 yuan to a dollar mark in May 2006 and rose to 7.81 per dollar in January 2007, rasing in value by more than 6 percent since July 2005.

Yuan rose 18.5 percent against the dollar between July 2005 and November 2008. Its value increased 6.9 percent against the dollar in the first sixth months of 2008. In April 2008 the yuan rose past 7 to the dollar for the first time since the fixed exchange rate ended in 2006. It broke the 7.5 to the dollar mark in October 2007. The yuan rose around 9 percent in 2007 and 4,4 percent in the first three months of 2008. The exchange rate for the yuan was 7.97 in 2006, 8.19 in 2005, 8.27 in 2002, 2003 and 2004.

The value of the yuan rose in 2006 partly out of the strength of the Chinese economy and partly out calls from Europe and the United States for it to reflect China’s trade surplus. Chinese officials also began have concerns that a low yuan might unleash inflation. The value of the yuan rose further in 2007 as the dollar weakened, Between July 2005 and July 2007, the value of the yuan rose 9 percent against the dollar. Some analysts have predicted the yuan will be traded freely after the 2008 Olympics, a move intended to curb excessive spending and cool the economy.

The yuan is still highly undervalued. This helps create trade surplus by making exports relatively cheap and imports expensive. The United States considered charging China with currency manipulation, undervaluing the yuan by as much as 40 percent, a move that could lead to trade sanctions if the WTO agreed with the charges.

To keep the yuan undervalued China has to buy dollars to prop up the dollar’s value. Buying dollars means exchanging them for Chinese currency and flooding China with yuan, which normally causes inflation which the Chinese government avoids by issuing bonds to take yuan out of circulation, a process the Chinese call “sterilization.” Interest rates are kept artificially low to keep investors from buying Chinese currency. The artificially low interest rates make it impossible for Chinese to control monetary policy. This means that loans to companies does not reflect their real value, which could create a bubble situation.. The United States and other want China to float the yuan.

When ever statistics released that show high growth rates and high trade surpluses for China there is pressure on China raise the value of the yuan, especially from the United States. See U.S. Pressure on the Value of the Yuan, See Macroeconomics

In 2007 the yuan gained more than 5 percent against the dollar and lost more than 5 percent against the Euro. It was valued at 7.42 yuan per dollar in November 2007.

China Becomes a Global Economic Power

Container ship packed with Chinese goods

In the early 2000s, China began emerging as a major global economic power, capable of competing with Japan, the United States and the European Union. Key to their long term strategy has been cementing their power in East Asia and spreading their influences and positioning themselves everywhere else.

In 2004 China became the world’s 4th largest economy. In 2005 The government stopped pegging the currency to the U.S. dollar. A government revision of economic growth figures for 2004 found that earlier estimates had underestimated the service industry economic growth to the tune of $280 billion, or 16.6 percent of GDP or the equivalent of the GDP of a country like Austria or Indonesia. The revision was enough to boost China from the world’s seventh largest economy past Italy, Britain and French to world’s forth largest economy after the United States, Japan and Germany.

The World Bank calculated that China contributed 29 percent to global economic growth in 2001. Demand from China for energy and mineral resources and agricultural products sent oil, iron, steel, cotton and soybean prices to record highs. See Oil, Resources, Agriculture

Chinese companies were involved in series of successful and attempted buyouts of major foreign companies. These included 1) the Lenovo Group’s buyout of the computer business of IBM: 2) Cnooc’s unsuccessful bid to buy Unocal; 3) Haier’s unsuccessful bid to buy Maytag. 4) Nanjing Motor Company’s takeover of MG Rover. The moves brought back memories of Japan buying Rockefeller Center, Universal Studios and Pebble Beach golf club.

The main Shanghai index doubled in 2006 and the value of all Chinese shares reached $1 trillion in January 2007, spurred on by a program to dispose of more $200 billion worth of mostly government-held equities. Mainland investors have pour $1.9 trillion of savings into equities as of 2006 as the Chinese government sold off state holdings.

Growth in China Continues

Growth was 9.1 percent in 2002, 10 percent in 2003,10.1 percent in 2004, 10.2 percent in 2005, 11.1 percent in 2006, 10.7 percent in 2006, 11.4 percent in 2007 and 10.6 percent in first quarter of 2007. Growth was predicted to be 9.6 percent in 2007 and is predicted to be 8.7 percent in 2008.

The growth rates in 2006 and 2007 were the highest since in 1996 and the forth double digit year in a row. The higher than expected figure was attributed to soaring exports, strong retail sales and consumer spending, massive investments in infrastructure, a manufacturing boom , growing affluence and the migration of rural people to the cities.. The growing occurred spite efforts by the Chinese government to cool down the economy. Even when Japan was going through its boom period in the 1980s the growth rate was only 5 percent.

There are few sings of economy slowing down. The average income of urban dwellers nearly doubled between 2001 and 2005. In 2005, China’s top 500 firms recorded a 23 percent rise in profits with particularly high earnings in the petrochemicals, natural gas exploitation, banking ad ferrous metals sectors.

Beijing aimed to slow growth to around 8 percent in 2007 by easing investment growth and reducing China’s trade surplus. It also hope to spread the wealth better by pumping more money into rural development projects and stimulate consumption by investing more in social welfare so that people would feel less need to save. China’s central bank raised borrowing costs six times in 2007 in an effort to slow growth and reduce inflation.

The government is worried about hoarding, speculation and bottlenecks creating inflation. It is trying to reign in the boom in real estate development and bank lend, worried about companies being left with huge debts and creating a bubble. Chinese banks have slowly gotten rid of bad loans. Moody raised China’s debt rating from “stable” to “positive” in July 2006. China remains dependant on borrowing heavily to build new factories and residential housing

In January 2007, Guangzhou became the first Chinese city to reach a per capita income of $10,000, often seen as the threshold for developed status, and considerably more than the $1,740 per capita income of China. Later the figure was lowered to $7,800 per capita because the $10,000 figure only included the city’s 7.5 million residents not the 3.7 migrants that lived there.

Boosting Consumption and Service in China

Beijing is trying to spur domestic consumption, tone down real-estate speculation, and reduce the reliance on exports and investment for growth. It has cut taxes and raised salaries of civil servants to encourage domestic spending and abolished or lowered taxes that affected the poor.

China needs to boost domestic consumption so that it is not vulnerable to disruptions, boycotts, and other problems that occur outside its borders. Prime Minister Wen Jibao said the spurring consumer spending was a national priority in 2006. Retail sales roses 13 percent in 2005 and were expected to rise 13.5 percent in 2006 but Chinese consumers remained frugal and growth was not enough to create jobs at the pace needed ti keep pace with jobs needed.

As of 2006, construction of factories and infrastructure still accounted for 41 percent of GDP and about half the economic growth.

Going hand and hand with this is the need to service industry to create jobs. See Services

Rise of the Chinese Stock Markets

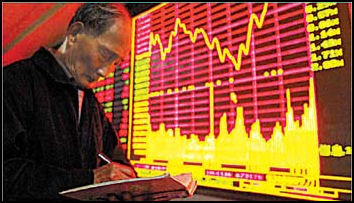

The Shanghai stock market dipped below 1,000 in early 2005 because of scandals, worries and structural problems. False accounting, disappearing IPO money were common and large state-owned companies were allowed to list on the markets without being genuinely private because of the government holding a lot of non-tradable shares. In one poll 90 percent of investors said they had lost money and public confidence was so low many thought of pulling their money out and never investing in the market again.

The Shanghai and Shenzhen markets were valued at around $1.4 trillion in December 2006, compared to $20 trillion on the New York Stock Exchange. Returns from the Shanghai composite index in 2006 were 130 percent, compared to 16.3 percent for the Dow Jones industrial average.

In January 2007 the Shanghai stock market rose to high of 2,933.19 less than two years after it dipped below 1,000. It was surprising that the market was doing so well because serious investors had traditionally distrusted it. The market had been growing steadily since the previous year, in part because of optimism spurred by state-owned companies doing something about shedding their non-tradeable shares.

The key Shanghai index rose 130 percent in 2006 and 70 percent in 2007. Million put their savings in stocks. Some investors doubled their investment in a month. One investor told AP, “I wanted to put all my energy into daily stock trading. The market was making millionaires every day, and I thought this my chance to be a young, wealthy ad successful person.”

The market was pushed up by an estimated 70 million investors’ many of them housewives and middle class, white-collar workers, even framers and laborers, who had invested large chunks of their savings. In Shanghai women at the beauty parlor talk about stocks and Stock Market Today is one of the highest ranked television shows. In Shenzhen, brokers were doing such good business they had computer terminals installed in the stairwells. The shear number of investors help propel the market to new heights.

Fall and Rise of the Chinese Stock Markets

In late February 2007 the Shanghai stock market collapsed, triggering a worldwide decline in stocks, with U.S. stocks having their worst day since September 11th. The free fall began after stocks on the Shanghai exchange hit record high and then slid 8.8 percent. When the market in New York opened stock fell dramatically and continued dropping steadily all day before taking a huge plunge in the late afternoon when computer-driven sell orders kicked in. The Dow fell 547.2 points, or 4.3 percent, to 12,086,06 before recovering in the last hour of trading to close down 416.02, or of 3.29 percent. The Nikkei was down 515 points to 2.85 percent for the day. Around the globe markets in Britain, Hong Kong. Seoul and Australia all fell more than two percent. In Sao Paul the market fell by 6.8 percent.

The sell offs in China were blamed on “ill-founded jitters,” “the immaturity of the market” and threats by the Chinese government to impose more regulations on the stock market and crackdown on illegal trading — not anything substantial in the markets Many saw the global drops simply as corrections that were long overdo and caused as much by concerns over Iran and an economic slowdown in the United States as by anything in China In any case, the event showed that China was becoming more and more a part of the world economy and the behavior of immature investors in China could make waves that could have an impact around the globe.

In January 2006, investors mostly ignored drops of 4.9 percent and 3.7 percent in the Shanghai Composite indexes — which each time recovered to new highs. Days after the February collapse, shares recovered 3.95 percent in Shanghai and Shenzhen. By May 2007 prices were up nearly 50 percent on the Shanghai stock exchange, with the Shanghai Composite index passing the 4,000 point mark for the first time.

In May 2007, for the first time, the volume of trading in the Chinese stock exchanges surpassed the rest of Asia combined — including Japan. The daily purchase of shares on May 9, 2007 on the Shanghai and Shenzhen markets totaled $49 billion. By contrast the volume in Japan was $25.9 billion and $16.5 billion in the rest of Asia, including Hong Kong and Singapore.

In the middle of 2007 Alan Greenspan said that the Chinese stock market was “in for a dramatic correction.” Investor Warren Buffet has said investors in China should be “cautious.” Investors for the most ignored them. By the end of 2007, the Shanghai stock market had gained over 100 percent for the year and stock markets in China had grown 400 percent.

The stock market peaked in mid October 2007, with the key Shanghai composite index reaching 6,124.04. After regulators suspended sales of mutual funds to new subscribers and the market fell, plummeting 50 percent by April 2008 and losing more than $1.7 trillion in market value. The decline was partly due to worries about inflation and shortages at home and concerns about the effects of economic problems in the United States on global markets. Some people saw gains they had made over months and years fall in a matter of weeks.

Keeping the stock markets in China largely off limits foreign investors insulated the markets from the U.S. credit crisis but worries about a U.S. recession and its effect on Chinese exporters took its toll. In April 2008, after the government cut the tax on equity trading, the Shanghai Composite rose 9.6 percent, the largest gain in more than six years.

Rising Inflation in China and Crashing Real Estate Market

Shanghai condominiums

Prices, wages and inflation rose in 2007 and there were concerns that China might begin exporting inflation rather than deflation. The government responded by insuring some prices freezes. It was quite remarkable that China was able to maintain high growths for a s long as did without igniting inflation.

Inflation rose 5.6 percent in July, 6.5 percent in August, 6.2 percent in September, 6.5 percent in October, 6.9 percent in November, 2007 from the same months the previous year, the highest levels in a decade, primarily as the result of higher food prices, particularly for meat. The price for pork rose nearly 50 percent as result of a pig disease. Vegetable and grain prices also rose as a result of crop-damaging floods. The price rises were good news for farmers.

In mid 2007 the price milk rose dramatically and the cost of peanut cooking oil nearly doubled in two months. The price of meat rose so high that many people substituted tofu for it. In October, retail prices rose a record high of 18 percent. In November 2007, the price of diesel and gasoline was raised by almost 10 percent to tackle the problem of fuel shortages resulting from a lack of refining capacity and the steep rise in oil prices. This move came only a two months after prices of oil products were frozen to curb inflation.

Food prices jumped 23.3 percent and inflation reached a 12-year high of 8.7 percent in February 2008 . In January they rose 7.1 percent. In March they rose 8.3 percent. In April they rose 8.5 percent Again high food prices were the main culprit. The jump helps farmers but is particularly hard on poor families that spend half their income on food. Pork price jumped 63,4 percent from February of 2007 while vegetables were up 46 percent.

Inflation ate away at the purchasing power of ordinary Chinese and made saving difficult. The annual inflation rate of 4.6 percent exceeding the one-year bank account deposit rate of 3.87 percent. There were also worries that China might exports its inflation abroad. In response to worries that inflation could get out hand Beijing suddenly tightened its monetary policy and imposed price freezes on cooking oil, flour, rice, noodles, electricity, water and other essentials. There were worries that this move might produce shortages and a black market. The government responded to this by boosting penalties for hoarding and price-fixing up to 1 million yuan ($130,000), ten times the previous penalties. .

In 2007 the housing market in Shenzhen tanked after state-owned banks stopping giving loans and China’s central bank raised interest rates six times and increased reserve requirements eight times as parts of its tight money policy. With a matter weeks apartments went from fetching record prices to be unable to find buyers, forcing real state agents to position themselves on roads and beg people driving to stop and look and their properties.

Chinese Economy in 2008

China weathered the U.S. subprime mortgage crisis better than expected In early 2008, output slowed as a result of a decrease in exports, connected with the subprime mortgage crisis in the United States, and bad weather, namely the devastating ice and snow storms that hit central China.Growth slowed to 10.6 percent in the first quarter of 2008. The trade surplus shrunk in 2008 for the first time in five years. It was affected by rising value of currency and the economic slowdown in the United States.

The Sichuan earthquake in 2008 had a relatively minor affect on the national economy of China. In May 2008, tariffs on some import items such as food and drugs were cut to combat inflation and help victims of the Sichuan earthquake. Growth fell to 10.1 percent in the second quarter of 2008. Some analyst were amazed that the number was as high it was considering the fact that China had experienced a devastating earthquake in May and the global economy was sputtering.

Growth fell to 9 percent in the third quarter of 2008 as export orders shrank and industrial production waned. Growth was affected by the global credit crisis and weakness in the domestic property sector. It was the first time growth fell into single digits in four years. It was difficult to say exactly what the statistics meant because the third quarter included the Beijing Olympics, which ended up slowing growth rather than spurring it as people watched the games on television rather than worked and factories were closed to reduce pollution.

Inflation was 8.6 percent in February 2008, it eased to 7.7 percent in May 2008 and was 7.1 percent in July. Food prices rose less because of price controls. Inflation dropped to a 14-month low of 4.9 percent in August, and fell further to 4.3 percent in September and 4 percent in October and 2.4 percent in November as food and energy costs eased and economic growth slowed.

See Energy Prices

The Olympics tacked on about 2 percent of growth a year onto Beijing’s economy during the seven years before the event, mainly through construction of venues and infrastructure, but didn’t generate that much economic activity nationwide. The Olympics is many ways hurt the economy. Production was down as factories were closed to reduce pollution and some travel sectors fell off. So many condominiums were produced there was a glut, causing real estate prices to fall and units to go unsold. After the Olympics there was not a big lull as work accelerated on high-speed railway between Beijing and Shanghai and preparation picked up for the World Expo in Shanghai and the Asian Games in Guangzhou in 2010.

But still, growth figures weren’t bad. China recorded 6.88 percent growth in final quarter of 2008 and 9 percent growth in for 2008 as a whole.

Image Sources: 1) University of Chicago; 2) University of Washington; 3) NY nerd; 4) China Daily ; 5) New York Times;

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2011