CHINA’S STATE CONTROLLED ECONOMY

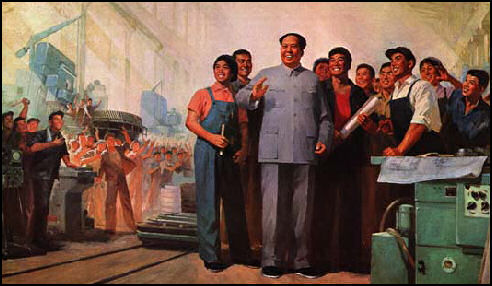

PLA factory John Lee wrote in Newsweek, “The state remains a significant player in the Chinese economy. State businesses receive more than three quarters of the country’s capital. The state owns more than 65 percent of the country’s fixed assets. This means local officials — who make more than three quarters of all state investment decisions — have an overwhelming influence on running these state businesses. They control the dispensation of capital, land, and sometimes even labor. Climbing the greasy ladder of status, power, and wealth within China’s vast political and bureaucratic network depends on results. And results are usually defined by whether the dominant state-controlled sectors in one’s township, city, or county are meeting centrally mandated targets. [Source: John Lee, Newsweek, July 30, 2010, Lee is a foreign-policy research fellow at the center for Independent Studies and a visiting fellow at the Hudson Institute in Washington, D.C. He is the author of “Will China Fail?” ]

The Chinese government controls the majority of large companies in the country. In many fields and industries, resources have been accumulated and controlled by several state-owned, monopolistic enterprises. According to China's Ministry of Finance, assets of all state enterprises in 2008 totaled about $6 trillion, equal to 133 percent of annual economic output that year. By comparison, total assets of the agency that controls government enterprises in France, whose dirigiste policies give it one of the biggest state sectors among major Western economies, were “539 billion ($686 billion) in 2008, about 28 percent of the size of France's economy. [Source: Jason Dean, Andrew Browne and Shai Oster.Wall Street Journal, November 16 2010]

The government's increased involvement in sectors from coal mining to the Internet has spawned the phrase guojin mintui, or "the state advances, the private sector retreats," among market proponents in China. A January 2010 report by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development said China's economy had the least competition of 29 surveyed, including Russia's. Prominent Chinese economist Qian Yingyi has said he worries over what appears to be "a reversal of market-oriented reforms in the last couple of years."

The state’s share of the economy fell from around 80 percent in 1997 to 35 percent in 2006. But this figure is misleading. The state still exerts a strong influence on the economy: it controls at least half of the economy, 70 percent if you include the state-owned companies that operate as private firms. There are no true free markets as the state manipulates the stock market, fixes prices in key industries and staffs banks with Communist Party members who tell the banks who they should lend to and what to invest in.

The Chinese government can manipulate the economy in ways that Western government’s can’t. In 2008, for example, when the housing market was starting to overheat it simply ordered banks to reduce the number of housing loans. When sales slowed too much it offered market incentives like lower taxes on home purchases. The Chinese government also can do things like order large state industries to buy new assets at home and abroad.

The Chinese bureaucracy dislikes the unpredictable nature market economy and does its best to control it by control pricing and production where it can. Rana Foroohar wrote in Newsweek, “China’s faith in its ability to mold markets may derive from the fact that its leaders are mostly engineers, trained to build from a plan. Eight of nine top party officials come from engineering backgrounds, and the practicality of their profession may help explain why they didn’t buy into risky (and Western) financial innovation. These ruling engineers preside over a system that is highly process oriented and obsesses with performance metrics.”

To avoid mistakes made by former Soviet countries China has proceeded cautiously into privatization. I sold off small enterprises with low profit margins and held on to the biggest and most profitable industries and one with the biggest cash flow. Today the state remains in control of natural resources such as oil, gas and coal; the production of steel and other metals; telecommunication, transportation, power generation and the financial system.

Wang Dang, a student leader at Tiananmen square and a Harvard Ph.D., wrote: “Riddled with corruption, the system has benefitted a privileged few, with local party secretaries becoming capitalists overnight and using their political power to accumulate huge sums of money from profits of state-owned enterprises.”

History of the State Controlled Economy Since the Deng Economic Reforms Were Launched

PLA (army) factory in Wuhan The state has always played a big role in China's economy, but for most of the reform era that started in the late 1970s, it retreated as state-owned collective farms were dismantled and inefficient state industrial enterprises closed. Accession to the WTO in 2001 represented a big bet by the leadership on liberalizing markets further. The gamble paid off, with growth rocketing much of the past decade. [Source: Jason Dean, Andrew Browne and Shai Oster.Wall Street Journal, November 16 2010]

But the state is again ascendant. Many analysts say the pace of liberalization has slowed, and point to vast swaths of industry still controlled by state companies and tightly restricted for foreigners. The government owns almost all major banks in China, its three major oil companies, its three telecom carriers and its major media firms.

In February 2011, the Chinese government began demanding that state firms hand over more profits to the government as part of a reform drive shift resources to consumer spending and small businesses.

China’s State Controlled Economy and Government Policy

The government does have powerful levers in its possession to adjust the direction of its economy. For instance, it controls the majority of large companies in the country. As such, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have better access to credit. But for many economists, this is a poor allocation of resources as the more competitive private sector is the main source of employment in China. "We know that the SOEs are a lot more powerful than they used to be," said Richard McGregor, author of "The Party: The Secret World of China's Communist Rulers." [Source: Jason Dean, Andrew Browne and Shai Oster.Wall Street Journal, November 16 2010]

By some estimates China's public procurement totals $1 trillion, or 6.8 trillion yuan, a year — about 20 percent of the total economy. The state's huge role in the economy gives it enormous sway to pursue its policy goals, which are often laid out in voluminous five-year (sometimes 15-year) plans. These relics of the Mao-era command economy are central to the corporate fortunes of Western giants like Caterpillar Inc. and Boeing Co. that rely on the country's market. China is now one of the biggest sources of revenue growth for Caterpillar, and is the biggest buyer of commercial jets outside the U.S., according to Boeing.

One of Beijing's most important goals: wean China off expensive foreign technology. It is a process that began with the "open door" economic policies launched by Deng Xiaoping in 1978 that brought in waves of foreign technology firms. Companies such as Microsoft Corp. and Motorola Inc. set up R&D facilities and helped train a generation of Chinese scientists, engineers and managers.

That process is now in overdrive. In 2006, China's leadership unveiled the "National Medium- and Long-Term Plan for the Development of Science and Technology," a blueprint for turning China into a tech powerhouse by 2020. The plan calls for nearly doubling the share of gross domestic product devoted to research and development, to 2.5 percent from 1.3 percent in 2005.

Most respondents to a Bloomberg poll felt confident of the Chinese government’s ability to fend off demands for greater political liberalization. Just 1 percent expect a political crisis within the next year and 27 percent expect one within the next two to five years. [Source: David J. Lynch, Bloomberg, Business Week January 26, 2011]

Mao at a factory

China as a Giant Corporation

In a review of the book “China’s Megatrends: The Eight Pillars of a New Society” by futurologist John Naisbitt and his wife, William A. Callahan wrote in China Brief: Rather talking about the PRC as a nation-state, many Chinese entrepreneurs’ see China as a corporate enterprise. This formulation caught the Naisbitts’ attention, leading them to conclude that “China has reinvented itself as if it were a huge enterprise.”

This appeal to corporate governance also helps explain the Naisbitt’s idea of vertical democracy: people in corporations don’t have rights, they have tasks; a corporation is not a commonwealth organized for the good of its members — its purpose is profit. As the Naisbitts explain, “survival of the company has to take priority over individuals’ interests and benefits. Those who would prefer to fight against the company’s culture and goals would have to choose: leave or adjust.” Since this is a country we are talking about, I suppose resigning means you leave China, while being fired means you end up in jail.

This shift from the PRC as a nation-state to China as a corporation clarifies how a free-market capitalist like John Naisbitt can so enthusiastically endorse CCP rule: both are pursuing an authoritarian capitalist model of governance, at the expense of democracy and social welfare. [Source: William A. Callahan, China Beat, November 15, 2010, William A. Callahan is Professor of International Politics at the University of Manchester and author of China: The Pessoptimist Nation (Oxford University Press, 2010)]

China’s Central Bank

The Communist Party manages the economy by committee. China’s central bank is not independent but answers to a ruling State Council that juggles the sometimes conflicting priorities of the country’s exporters, state-owned companies, local governments and other factions. [Source: Howard Schneider, Washington Post , April 19 2011]

The absence of a top autonomous central banker — Beijing has no equivalent of the United States Federal Reserve chairman — means no one actually has a hand on key aspects of controlling the economy. Interest rates are set by the government. Banks follow benchmark rates set by the banks. Some analysts believe the Chinese economy, banks, lenders and borrowers all will benefit if interest rates are liberalized and banks are given discretion to set their own rates, working out the risks and profits that can be made themselves.

China’s Authoritarian Model

One major impacts that China has had on the global economy is the spread of the authoritarian model — China’s economic approach of carefully controlled reform, a strategy once described by the late Communist Party patriarch Chen Yun as “crossing the river by feeling for the stones.” (It is wrongly credited to Deng Xiaoping most of the time.)

“The Beijing Consensus” by Stefan Halper of Cambridge is careful analysis of the impact of the Chinese authoritarian model.

The government can do pretty much what it wants to do, There are no real checks on its power. There is no powerful legislature or free press to scrutinize projects and subject them to open debate where many different viewpoints are considered. As long as the government acts in the public interest and is not too consumed by corruption it has a high degree of flexibility and assertiveness not possible in Western democracies.

“The Chinese politicians are able to act on all necessary issues. That gives them a huge advantage compared to the Western economies,” says Henry Littig, who heads his own global investment firm in Cologne, Germany. [Source: David J. Lynch, Bloomberg, Business Week January 26, 2011]

Chinese State-Controlled Companies

The Economist reported: “Since 1993 Beijing has encouraged gaizhi for state-owned enterprises, which means “changing the system”. Between 1995 and 2001 the number of state-owned and state-controlled enterprises fell by nearly two-thirds, from 1.2 million to 468,000, and the proportion of urban workers employed in the state sector fell by nearly half, from 59 percent to 32 percent. Yet gaizhi is not simply a euphemism for “privatisation”; it has also created a variety of public-private hybrids.” [Source: The Economist, September 3, 2011]

At one end of the spectrum are the giant state-controlled enterprises in industries which the government considers “strategic”, such as banking, telecoms or transport. Such firms may have sold minority stakes to private investors, but they operate more or less like government ministries. Examples include China Construction Bank, a huge backer of infrastructure projects, and China Mobile, a big mobile-phone carrier.

Next come the joint ventures between private (often foreign) companies and Chinese state-backed entities. Typically, the foreign firm brings technology and its Chinese partner provides access to the Chinese market. Joint ventures are common in fields such as carmaking, logistics and agriculture.

A third group of firms appears to be fully private, in that the government owns no direct stake in them. Their bosses are not political appointees, and they are rewarded for commercial success rather than meeting political goals. But they are still subject to frequent meddling. If they are favoured, state-controlled banks will provide them with cheap loans and bureaucrats will nobble their foreign competitors. Such meddling is common in areas such as energy and the internet.

A fourth flavour of Chinese firm is fuelled by investment by local government, often through municipally owned venture-capital or private-equity funds. These funds typically back businesses that dabble in clean tech or hire locals.

These firms with their various sorts of state influence have several strengths. They invest patiently, unruffled by the short-term demands of the stockmarket. They help the government pursue its long-term goals, such as finding alternatives to fossil fuels. They build the roads, bridges, dams, ports and railways that China needs to sustain its rapid economic growth.

But statism has big costs, too. The first is corruption. When local bigwigs can award contracts to firms which they themselves control, graft spreads like bird flu. Sometimes well-connected shell firms take a fat cut and then pass the real work on to subcontractors, with scant regard for standards. The second problem is that big state-backed enterprises crowd out small entrepreneurial ones. They gobble up capital that China’s genuinely private firms could use far more efficiently, amassing bad debts that will eventually cause China big trouble. They rig the game in other ways, too, enjoying privileged access to land and permits. Small private firms are often unsure whether what they do is even legal. The rise of local-government venture funds creates yet more opportunities for abuse. Some of these funds will invest wisely, but many will pursue non-commercial goals, from job creation to crony enrichment.

Not so long ago, government-controlled companies were regarded as half-formed creatures destined for full privatization. But a combination of factors — huge savings in the emerging world, oil wealth and a loss of confidence in the free-market model — has led to a resurgence of state capitalism. About a fifth of global stockmarket value now sits in such firms, more than twice the level ten years ago.

State-Owned Enterprises in China

State-run industry concentrated in the industrial heartland in the northeast provinces of Liaoning, Jilin and Heilongjiang and dominated industries such machinery production, transportation, energy and finance. Over the years they have sucked up billions of dollars in subsidies; produced goods nobody wanted; and were kept operating by loans that couldn’t be paid back. They are swamped in debt, surplus labor, inefficient equipment, over-stocked inventories and corrupt, inept management.

State-run industry The were also notoriously unproductive. A state factory worker told National Geographic, "the bosses had nothing to do all day except smoke cigarettes and read newspapers." A manager said that in his company bosses, appointed by the Communist Party, often showed up late wearing shorts and slippers and things that should have taken half a day to do took three days.

The books of state-owned enterprises were often cooked to make the company appear profitable when in actually they were losing heaps. There At one point 50,000 state enterprises sucked up 70 percent of all domestic loans while producing less than 34 percent of industrial output.

In 1978, 78 percent of business were state owned and 22 percent were collectively owned. In 1995, 34 percent of business were state owned, 37 percent were collectively owned, and 29 percent were privately owned. In 1996, an estimated 6,000 state-owned enterprises went bankrupt and the debts of those still in business was 95 percent of their assets.

In 2001, there were still 110,000 state-run enterprises, with 63 percent of them losing money. These factories employed 109 million people. Finally by the mid 2000s, the last unprofitable state-owned businesses were being closed or privatized, with a few state-owned enterprises emerging as solid profitable institutions. By 2006, state-owned enterprises generated only 10 percent of China’s industrial output.

Communist party leaders still want public ownership. They worry that too much privatization will undermines their power. Should let inefficient industries go bankrupt but there are concerns about social unrest if too many people loose their jobs. Fearful of labor unrest and unemployment the government back away from its plan to sell 100,000 state-owned enterprises even though half of them were losing money.

In March 2005, an official announced that the government would stop propping up bankrupt state-run enterprises within four years. He said five provinces or cities — Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang and Fujian — had already done so.

See State Workers, Types of Jobs, Labor

State Capitalism in China: State-Owned Enterprises on the March

The Economist reported: when China joined the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in December 2001, many people hoped that this would curb the power of its state-owned enterprises. Ten years on, they seem stronger than ever. A Congressional report released on October 26th railed against the unfair advantages enjoyed by state-owned firms and lamented that China is giving them “a more prominent role”. [Source: The Economist, November 12, 2011]

Indeed it is. In a new book called “China’s Regulatory State”, Roselyn Hsueh of Temple University documents how, in sectors ranging from telecommunications to textiles, the government has quietly obstructed market forces. It steers cheap credit to local champions. It enforces rules selectively, to keep private-sector rivals in their place. State firms such as China Telecom can dominate local markets without running afoul of antitrust authorities; but when foreigners such as Coca-Cola try to acquire local firms, they can be blocked (though this week China did approve Yum! Brands’ bid to acquire Little Sheep, a Chinese restaurant chain).

In the dozen or so industries it deems most strategic, the government has been forcing consolidation. The resulting behemoths are held by the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC), which is the controlling shareholder of some 120 state-owned firms. In all, SASAC controls $3.7 trillion in assets. The Boston Consulting Group (BCG) calls it “the most powerful entity you never heard of”; though it does not always get its way. Some state-owned firms have powerful friends and are hard to push around.

In some ways, SASAC aims to modernise its enterprises. Peter Williamson of Cambridge’s Judge Business School points approvingly to the steel industry. China was once littered with small, uneconomic steel firms; SASAC has urged them to merge, creating three “emperors” and five “kings”. That, says Mr Williamson, means there are enough steel firms to foster competition at home; yet they are big enough to venture overseas. What the government’s plan lacks, however, is any idea that private steelmakers might compete, in China, with the emperors and kings.

According to the Congressional report, state-owned firms account for two-fifths of China’s non-agricultural GDP. If firms that benefit from state largesse (eg, subsidised credit) are included, that figure rises to half. Genuinely independent firms are starved of formal credit, so they rely on China’s shadow banking system. Fearing a credit bubble, the government is cracking down on this informal system, leaving China’s “bamboo capitalists” bereft.

Those who argue that state-owned firms are modernising point to rising profits and a push to establish boards of directors with independent advisers. Official figures show that profits at the firms controlled by SASAC have increased, to $129 billion last year. But that does not mean that many of these firms are efficient or well-managed. A handful with privileged market access — in telecoms and natural resources — generate more than half of all profits. A 2009 study by the Hong Kong Institute for Monetary Research found that if state-owned firms were to pay a market interest rate, their profits “would be entirely wiped out”.

One reason is that state firms must pursue the state’s aims, which include many things besides making profits. David Michael of BCG observes that the government forces state firms to shoulder all manner of extra costs. For example, when coal prices shot up recently, the country’s energy giants were not allowed to pass the hikes on to consumers. When the China Europe International Business School asked its senior alumni at state-owned firms about their biggest headaches, many grumbled about official meddling.

Still, Mr Michael, who served as one of the only foreigners on China Mobile’s advisory board, believes SASAC deserves some praise. The group runs management-training courses, benchmarks firms against international standards and establishes codes of conduct. Following recent scandals involving Chinese firms overseas, it issued an edict in July restricting the use of derivatives by the main state-owned firms. And SASAC is now pushing the biggest of its charges to appoint boards of directors.

Yet Curtis Milhaupt of Columbia Law School insists that such reforms are “not where the action is”. In a new paper, he examines how exactly China’s big state firms are controlled, and reaches troubling conclusions. Regardless of whether a state-owned firm is listed in New York, has an “independent” board or boasts a market-minded chairman with a Harvard MBA, he finds that the strings always lead back to a core company that is in the tight clutches of SASAC. He thinks genuine market reform will come only when state firms venture abroad en masse and have to adapt to global norms.

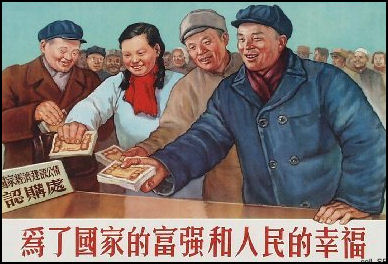

Busy supermarket

Chinese Economic Advances the Result of Individual Enterprise People Rather Than Government Policy

Liu Junning wrote in the Wall Street Journal, “China has indeed made great strides since 1978's "Reform and Opening" in alleviating poverty, opening up to the world, and making slow steps down the road of legal reform. Yet on closer inspection, the most significant transformations from the perspective of boosting prosperity have involved loosening of control over the people, not some alchemy of power and Marxism. [Source: Liu Junning, Wall Street Journal, July 6, 2011]

“This becomes clear in comparing China's economic performance during periods when Beijing has been more closely versus less closely following the Beijing Model. According to MIT economist Yasheng Huang, "[W]hen measured by factors that directly track the living standards of the average Chinese person, China has performed the best when it pursued liberalizing, market-oriented economic reforms, as well as conducted modest political reform, and moved away from statist policies."

In his book, “Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics,” Huang argues that, for all the talk of reform, China underwent “in fact a substantial reversal of reforms” during the nineteen-nineties. GDP growth in the PRC has averaged more than 9 percent since 1989 and reached as high as 14.2 percent in 1992 and 2007, according to the World Bank.

China’s Bamboo Capitalism

The Economist reported: The secret of China’s economic success is often vaguely attributed to “capitalism with Chinese characteristics” — typically taken to mean that bureaucrats with heavy, visible hands have worked much of the magic. That, naturally, is a view that China’s government is happy to encourage. But is it true? Of course, the state’s activity has been vast and important. It has been effective in eradicating physical and technological obstacles: physical, through the construction of roads, power plants and bridges; technical, by facilitating (through means fair and foul) the transfer of foreign intellectual property. Yet China’s vigour owes much to what has been happening from the bottom up as well as from the top down. Just as Germany has its mighty Mittelstand, the backbone of its economy, so China has a multitude of vigorous, (very) private entrepreneurs: a fast-growing thicket of bamboo capitalism. [Source: The Economist, March 10, 2011]

These entrepreneurs often operate outside not only the powerful state-controlled companies, but outside the country’s laws. As a result, their significance cannot be well tracked by the state-generated statistics that serve as a flawed window into China’s economy. But as our briefing shows, they are an astonishing force.

First, there is the scale of their activities. Three decades ago, pretty much all business in China was controlled by one level of the state or another. Now one estimate — and it can only be a stab — puts the share of GDP produced by enterprises that are not majority-owned by the state at 70 percent. Zheng Yumin, the Communist Party secretary for the commerce department of Zhejiang province, told a conference last year that more than 90 percent of China’s 43 million companies were private. The heartland for entrepreneurial clusters is in regions, like Zhejiang, that have been relatively ignored by Beijing’s bureaucrats, but such businesses have now spread far and wide across the country.

Second, there is their dynamism. Qiao Liu and Alan Siu of the University of Hong Kong calculate that the average return on equity of unlisted private firms is fully ten percentage points higher than the modest 4 percent achieved by wholly or partly state-owned enterprises. The number of registered private businesses grew at an average of 30 percent a year in 2000-09. Factories that spring up alongside new roads and railways operate round-the-clock to make whatever nuts and bolts are needed anywhere in the world. The people behind these businesses endlessly adjust what and how they produce in response to extraordinary (often local) competition and fluctuations in demand. Provincial politicians, whose career prospects are tied to growth, often let these outfits operate free not only of direct state management but also from many of the laws tied to land ownership, labor relations, taxation and licensing. Bamboo capitalism lives in a laissez-faire bubble.

Problems with Bamboo Capitalism: a Lack of Clear Rules and an Abuse of This Situation

But this points to a third, more worrying, characteristic of such businesses: their vulnerability. Chinese regulation of its private sector is often referred to as “one eye open, one eye shut”. It is a wonderfully flexible system, but without a consistent rule of law, companies are prey to the predilections of bureaucrats. A crackdown could come at any time. It is also hard for them to mature into more permanent structures.

All this has big implications for China itself and for the wider world. The legal limbo creates ample scope for abuse: limited regard for labor laws, for example, encourages exploitation of workers. Rampant free enterprise also lives uncomfortably alongside the country’s official ideology. So far, China has managed this rather well. But over time, the contradictions between anarchic opportunism and state direction, both vital to China’s rise, will surely result in greater friction. Party conservatives will be tempted to hack away at bamboo capitalism.

It would be much better if they tried instead to provide the entrepreneurs with a proper legal framework. Many entrepreneurs understandably fear such scrutiny: they hate standing out, lest their operations become the focus of an investigation. But without a solid legal basis (including intellectual-property laws), it is very hard to create great enterprises and brands.

The legal uncertainty pushes capital-raising into the shadows, too. The result is a fantastically supple system of financing, but a very costly one. Collateral is suspect and the state-controlled financial system does not reward loan officers for assuming the risks that come with non-state-controlled companies. Instead, money often comes from unofficial sources, at great cost. The so-called Wenzhou rate (after the most famous city for this sort of finance) is said to begin at 18 percent and can even exceed 200 percent. A loan rarely extends beyond two years. Outsiders often marvel at the long-term planning tied to China’s economy, but many of its most dynamic manufacturers are limited to sowing and reaping within an agricultural season.

So bamboo capitalism will have to change. But it is changing China. Competition from private companies has driven up wages and benefits more than any new law — helping to create the consumers China (and its firms) need. And behind numerous new businesses created on a shoestring are former factory employees who have seen the rewards that come from running an assembly line rather than merely working on one. In all these respects the private sector plays a vital role in raising living standards — and moving the Chinese economy towards consumption at home rather than just exports abroad.

The West should be grateful for that. And it should also celebrate bamboo capitalism more broadly. Too many people — not just third-world dictators but Western business tycoons — have fallen for the Beijing consensus, the idea that state-directed capitalism and tight political control are the elixir of growth. In fact China has surged forward mainly where the state has stood back. “Capitalism with Chinese characteristics” works because of the capitalism, not the characteristics.

China’s State Capitalism

Central to China's approach are policies that champion state-owned firms and other so-called national champions, seek aggressively to obtain advanced technology, and manage its exchange rate to benefit exporters. It leverages state control of the financial system to channel low-cost capital to domestic industries — and to resource-rich foreign nations whose oil and minerals China needs to maintain rapid growth. [Source: Jason Dean, Andrew Browne and Shai Oster, Wall Street Journal, November 16 2010]

China's policies are partly a product of its unique status: a developing country that is also a rising superpower. Its leaders don't assume the market is preeminent. Rather, they see state power as essential to maintaining stability and growth, and thereby ensuring continued Communist Party rule.

It's a model with a track record of getting things done, especially at a time when public faith in the efficacy of markets and the competence of politicians is shaken in much of the West. Already the world's biggest exporter, China is on track to pass Japan this year as the second-biggest economy.

China's strategy echoes the policies Japan employed in its economic rise — policies that also rankled the U.S. But China's sheer scale — its population is 10 times Japan's — makes it a more formidable threat. Also, its willingness in recent decades to open some industries to foreign firms makes its market far more important for global business than Japan's ever was, giving Beijing much greater leverage.

China’s State Capitalism Sparks Global Backlash

Charlene Barshefsky, who as U.S. trade representative under President Bill Clinton helped negotiate China's 2001 entry into the World Trade Organization, says the rise of powerful state-led economies like China and Russia is undermining the established post-World War II trading system. When these economies decide that "entire new industries should be created by the government," says Ms. Barshefsky, it tilts the playing field against the private sector. [Source: Jason Dean, Andrew Browne and Shai Oster.Wall Street Journal, November 16 2010]

Western critics say China's practices are a form of mercantilism aimed at piling up wealth by manipulating trade. They point to China's $2.6 trillion in foreign-exchange reserves. The U.S. and the European Union have lodged a series of WTO cases and other trade actions targeting Beijing's policies, and hammer China's refusal to let its currency appreciate more quickly, which they argue fuels global economic imbalances.

Top executives at foreign companies have started griping publicly. In July, Peter Löscher, Siemens AG chief executive, and Jürgen Hambrecht, chairman of chemical company BASF SE, in a public meeting between German industrialists and China's premier, raised concerns about efforts to compel foreign companies to transfer valuable intellectual property in order to gain market access.

Some observers think Beijing's vision is rooted in a desire to avenge China's "century of humiliation" that started with the 19th-century opium wars. Such critics believe that China's focus on "indigenous innovation" — nurturing home-grown technologies — entails appropriating others' technology. China's high-speed trains, for instance, are based on technology introduced to China by German, French and Japanese makers.

"The Chinese have shown that if they have the ability to kill your model and take your profits, they will," says Ian Bremmer, president of New York-based consultancy Eurasia Group. His book, "The End of the Free Market," argues that a rising tide of "state capitalism" led by China threatens to erode the competitive edge of the U.S.

So far, though, multinationals aren't staying away, because China remains a vital source of growth for companies whose domestic markets are saturated.

Chinese leaders have begun to acknowledge the backlash. At the World Economic Forum in Tianjin in September, Premier Wen Jiabao said that the recent debate about China among foreign investors "is not all due to misunderstanding by foreign companies. It's also because our policies were not clear enough." "China is committed to creating an open and fair environment for foreign-invested enterprises," Mr. Wen said.

China’s Capital Controls: Set the Money Free

In March 2012 The Economist reported: Cheap capital has been crucial to China’s rise. The country’s growth has been fuelled by banks sucking up plentiful household savings and pumping them into not-always-deserving industry, including big, state-owned borrowers. There are costs to this approach. The skewed interest rates offered by China’s banks represent a tax on depositors and a subsidy for industry. They distort the economy, suppressing consumption, services and private business in favour of investment, industry and the state. Savers seeking to avoid being fleeced by the country’s banks inflate housing bubbles instead. And controls on capital outflows prevent sound investments abroad, resulting in large and dangerous piles of foreign-currency reserves. [Source: The Economist, March 3, 2012]

Ultimately, putting this right requires China to accept freer movement of capital within its borders, and across them. Yet opening a financial system to the outside world carries dramatic risks — witness the tide of hot money into China’s neighbours that led to the Asian financial crisis at the end of the 1990s. How, then, should China chart a safe course?

One Chinese organisation, at least, has been thinking about just that. The relatively liberal People’s Bank of China (PBOC) has just circulated a study that recommends opening up the financial system, with a ten-year timetable for easing capital restrictions. It would start by encouraging Chinese businesses to buy foreign companies — many of which, the report points out, are going cheap right now. Next would come greater cross-border commercial lending, including loans in Chinese currency. After that, foreigners could invest more freely in Chinese shares, bonds and property. Remaining controls could be lifted at the government’s discretion, with suitable curbs on “speculative” capital flows staying in place indefinitely.

This makes sense — as far as it goes. China’s excess saving is currently funnelled through the central bank into (overpriced) American Treasuries and similar bonds. This appetite for safe securities encouraged Western banks to create synthetic, AAA assets that later turned toxic, with ruinous results. China’s direct investments abroad, in firms and factories, amount to less than Sweden’s. Looser controls would encourage more productive investments that are less likely to unbalance the world economy.

China, unlike many emerging economies, does not need foreigners’ money. Its own people and firms save more than enough. Yet it could use a more cosmopolitan mix of capital. Foreign investors might help finance the parts of China’s economy its banks do not reach, such as entrepreneurial companies. Their presence might also deepen and diversify China’s skittish financial markets. And the yuan will not become a successful international currency — as China’s leaders want — unless foreigners can use it to buy and sell Chinese assets.

For all these reasons, the central bank seems keen for the government to get a move on. But it needs to get the timing right. If China eases capital controls at its border before easing those within the country, there could be a rush for the door as depositors in China’s state-owned banks hurry to put their money in foreign bank accounts or stockmarkets. Unless domestic interest rates are liberalised first, to give savers a reason to keep their money in the Chinese banking system, China’s financial system might fall apart.

The rulers’ inclination is to do nothing. Reform would be risky, and would carry political dangers for a government that fears losing control — especially to foreigners. Yet inaction also poses risks. China’s leaders know that the country needs to keep growing fast to remain politically stable. If it is to do that, capital needs to be more efficiently allocated.

China can minimise the dangers of liberalisation by preparing the path. Thus any scheme to free up the capital account should also liberalise interest rates and the exchange rate, overhaul monetary policy, improve the way Chinese banks are run and supervised, and foster deeper, better-regulated financial markets. Domestic and international liberalisation can complement each other. Foreign competition can force Chinese banks to raise their game. The movement of capital in pursuit of the best returns also prevents domestic interest rates from getting too far out of line. At this stage of its development, China’s financial reforms will work best in tandem. But to prevent bubbles and crashes, capital-account liberalisers should remain in the back seat while the domestic reformers keep pedalling.

World Bank Says China Needs Sweeping Reforms

In February 2012, AP reported: China needs to reduce the dominant role of state companies in its economy and promote free markets to keep growth steady and avoid potential crises, the World Bank and Chinese researchers said Monday. The recommendations, in a report on China's development through to 2030, come amid a debate in the ruling inner circle over the future course of economic reform as a new generation of leaders prepares to take office this year. [Source: Joe McDonald, Associated Press, February 27, 2012]

The emphasis on curbing state industry clashes with Beijing's strategy over the past decade of building government-owned champions in fields from banking to technology and is likely to provoke opposition. "As China's leaders know, the country's current economic growth model is unsustainable," said World Bank president Robert Zoellick at a conference about the report. He said China has reached a "turning point" and needs to "redefine the role of the state."

Its recommendations highlight the fact that after three decades of reforms that allowed Chinese entrepreneurs to become world leaders in export-driven manufacturing, state companies still control domestic industries from steel to airlines to oil to telecommunications. Government companies are supported by low-cost credit from government banks and business groups complain regulators shield them from foreign and private competitors despite Beijing's market-opening pledges.

China's leaders have promised repeatedly to support entrepreneurs who create most of its new jobs and wealth. But most bank lending still goes to state companies and Beijing's huge stimulus in response to the 2008 crisis set back reforms by pouring money into government industry while thousands of private companies went bankrupt.

A summary of the report released by the World Bank recommended an array of politically thorny changes, including forcing state companies to compete with private rivals, basing bank lending on market forces and changing a household registration system that limits the ability of rural migrants to work in cities. Zoellick acknowledged they might face opposition from political factions that benefit from the old system. He said Beijing should make changes gradually to build support from new groups that profit from more open markets.

In a reflection of high-level support, Zoellick said work on the report began 18 months with an endorsement by President Hu Jintao and Vice President Xi Jinping. Xi is due to succeed Hu as China's paramount leader. Vice Premier Li Keqiang, a top economic official, gave "unwavering commitment to this project," Zoellick said.

"There will be many risks and challenges going forward, especially if China is unable to change its current pattern of growth," said Vikram Nehru, a former World Bank chief economist for East Asia and one of the report's lead authors. Nehru cited the need to support an aging population, competition for natural resources and potential environmental damage.

Zoellick contrasted China's ability to make changes with the difficulties faced by crisis-hit Italy and Spain in restructuring their economies amid little or no growth. "What I am picking up from discussions, not only in Beijing but with provincial party secretaries, is a recognition that it is better to undertake structural reforms while the economy is growing," he said.

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2012