CHINA AND THE WORLD

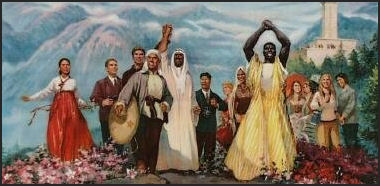

Mao-era foreign friends poster In less than 20 years China is expected to have the largest economy in the world. Once its army is modernized it also has the potential of becoming a military superpower.

Beijing has traditionally made policy decisions based on domestic concerns rather than foreign ones. But in recent years as it stature, wealth and role in the global economy have risen China seems more intent on making decision with foreign policy goals in mind and using its power abroad.

China is not really perceived as international threat namely because its military is not strong enough to project itself outside of China and it has too much to lose economically if it makes trouble abroad. China has said it has no ambitions of taking over territory beyond is borders other than Taiwan — which it regards as within its borders — in part because it has its hands full dealing with problems at home. China also has to deal with the fact that is dependant on the outside world for energy and other resources.

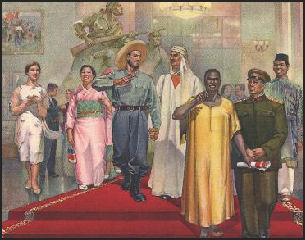

China often tries to ally itself with the developing world and offer itself as an alternative to the West. Under Mao, many poor countries found China to be an inspiration. Today China supports efforts to give developing nations a greater voice in the United Nations. There are some concerns in the West that developing nations may adopt the Chinese model to success — promoting economic growth while clamping down on political freedoms and human rights.

These days China is trying to promote itself as a kinder, gentler nation. In 2004, Hu Jintao introduced the foreign policy ideology “China’s Peaceful Rise” — embracing globalization while avoiding a Cold War-style confrontation with the West. The expression was later modified to “peaceful development” because “rise” was seen as sounding too aggressive.

In economic, political and diplomatic circles, often it seems that China is all anyone wants to talk about. China was at center stage of the Davos World Economic Forum in January 2006. That year more that half of the leaders of the world’s 192 countries visited China.

China is increasingly being seen by the United States and Europe as obstructionist when it comes to issues like global warming and Iran’s nuclear program.

There are virtually no fences along China’s 20,000-kilometer-long border. China has solved border disputes with Russia, Mongolia, Vietnam and Myanmar but has work to do to settle its disputes with India.

China only has extradition policies with 37 countries.

Articles on INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS AND FOREIGN POLICY factsanddetails.com

Views of China Abroad

In a survey by Pew Research Center in 2008, 77 percent of the Chinese asked said they thought that China was generally liked around the world. In a survey by Pew Research Center in 2009, only seven in 23 countries polled had majorities that had favorable impressions of China. Five countries viewed most positively in another survey were: 1) Canada (54 percent); 2) Japan (54 percent); 3) France (50 percent); 4) Britain (45 percent); 5) China (42 percent).

The number of people in Britain, the United States, France, Germany and Spain with a favorably view of China plunged between 2006 and 2008, with the decline as particularly notable, dropping from 60 percent in 2006 to 28 percent in 2008.

In 2007, the percentage of the population in the United States with a favorable opinion was China was 40 percent, compared to 48 percent in Britain, 47 percent in France 39 percent in Spain, 36 percent in Germany, 60 percent in Russia, 36 percent in Japan and 23 percent in Turkey.

China is like an adolescent who took too many steroids, said Liu Kang, a professor of Chinese studies at Duke University. It has suddenly become big, but it finds it hard to coordinate and control its body. To the West, it can look like a monster. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, December 12, 2009]

Kate Merkel-Hess and Jeffrey Wasserstrom wrote in Time: “Some foreigners disparagingly talk about China's flawed "cultural DNA," bequeathed to it, apparently, by a hierarchy-loving, conformity-prizing "Confucian" heritage. But damage is also being done by those within the country who repeat the Chinese leadership's simplistic mantra about China's unwavering love of "Confucian" stability and harmony.” [Source:Kate Merkel-Hess and Jeffrey Wasserstrom, Time , January 1 2011]

History of China’s International Relations

1920s international friendship poster

China has traditionally been very isolationist. For a long time there was a widespread view in China that its culture and society were at such high level there was little the rest of the world had to offer it. In the 19th century and much of the 20th century China portrayed itself as victim of Western, Japanese and American Imperialism. One Mao slog went: “Imperialism will never abandon its intention to destroy us.” Propaganda lines from a newspaper from the 1960s shouted: “American Imperialists get out of South Korea! Get out of Japan! Get out of South Vietnam! Get out of our nation’s territory Taiwan!”See History

Mao had ambitions to expand his revolution abroad. Under his rule, China entered foreign adventures in Korea, Vietnam and Cambodia; clashed over borders with the Soviet Union; cast the United States as a global villain; and launched a number of development projects in Africa and other developing nations. During much of the Maoist era, China’s closest ally was Albania.

Based on Karl Marx's view that the "the proletariat cannot liberate itself without liberating the whole of humankind", Mao's internationalism holds that Chinese people must support anti-oppression movements worldwide. Mao used to organize massive demonstrations at Tiananmen Square and issued statements to show Chinese people's support for "revolutionary" movements across the world. [Source: Asian Times]

Unlike the Soviet Union, China today is no longer in the business of exporting its ideology. Unlike the 19th-century European powers, it is not looking to amass new colonies. Foreign policy under Deng Xiaoping was characterized by the dictums “hide you ambitions and disguise your claws” and “lay low at a time of diversity,” which were taken to mean that China should devote its energy to developing economially and not concern itself with international affairs.

These days China pushes itself more as a responsible even sympathetic “great power.” One reason for China’s new friendly face relates to its position as major economic power and its need for other nations to buys it products and invest money. It widely believed that welcoming China into the community of nations will force it to abide by international standards, rules and laws.

China now has a presence almost everywhere in the world. It has worked trade agreements in Latin America; signed oil deals in Central Asia, the Middle East and Russia; and is engaged in infrastructure projects in Africa. And because China is so big it is involved in economic, social and political sectors that have an impact on the entire global community.

”When China Rules the World: the End of the western World and the Birth of a New Global Order” by Martin Jacques (Penguin Press, 2009)

China, National Humiliation and Foreigners

Suffering and humiliation at the hands of foreigners was a theme in Chinese history in the 19th century and 20th century. In the Opium Wars era, Britain subdued the Chinese population with Indian opium; made tons of money; and took over Chinese territory with humiliating unequal treaties. Later, the Russians and Japanese occupied the industrial north; European nations established "treaty ports" on the Chinese coast to exploit China's resources and labor; and, finally, Japan raped and pillaged China like medieval invaders before and during World War II. The Chinese describe their feelongs with the word “guochi”, or "the national humiliation."

Foreigners were aware of the way China was being exploited. In 1900, the future Russian revolutionary leader, Vladamir Lenin, said, "The European governments have robbed China as ghouls rob copses." A descriptive 1898 French lithograph showed Queen Victoria of Great Britain, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, the Japanese emperor Mutsuhito and Czar Nicholas II all sitting around a giant pizza, inscribed with China, dividing it up with butcher knives.

China expert Orville Schell wrote, “The most critical element in the formation of China’s modern identity has been the legacy of the country’s “humiliation” at the hands of foreigners, beginning with its defeat in the Opium Wars in the 19th-century and the shameful treatment of Chinese immigrants in America. The process was exacerbated by Japan’s successful industrialization, Tokyo’s invasion and occupation of the mainland during World War II, which in many ways was more psychologically devastating than Western interventions because Japan was an Asian power that had succeeded in modernizing, where China had failed.”

See China, National Humiliation and Foreigners in the article THEMES IN CHINESE HISTORY: PATTERNS, IDENTITY AND FOREIGNERS factsanddetails.com

China’s Impact on the World

Some have argued that China’s internal demands and problems are so great that China’s impact on the world and global policy will be limited except where they help solve internal problems’such as procuring natural resources — and China will not be a major foreign policy player like the United States or even Europe until it gets its domestic issues sorted out. If China becomes too absorbed in foreign issues it runs the risk of overextending itself and if it does that it does so at its own peril by risking losing a handle on internal problems. For that reason China must rely and become comfortable with the United States playing the role of global regulator because the U.S. protects interests and markets that China depends on.

China’s influence in the world has the risen as the influence of the United States has shrunk, especially after the U.S. has gotten bogged down in Iraq and lost respect and credibility for the way it handled things over there. In March 2005, a BBC survey found that 48 percent of the people asked in 22 countries had a positive view of China as a global power compared to 38 percent with a positive view of the United States.

Kissinger's On China

Rana Mitter, a professor of the history and politics of modern China at the University of Oxford, wrote in The Guardian: “Former US secretary of state Henry Kissinger's “ On China “ is an unusual and valuable book. Of all the westerners who shaped the post-second world war world — and there is little doubt that he did — he is one of the very few who made the American relationship with China the key axis for his world view. This is all the more remarkable since Kissinger's realpolitik also profoundly shaped American relations with Europe, the Middle East, and south-east Asia. Yet at four decades' distance, it is the approach to China in 1971 and 1972 that stands out as the historically crucial moment.” [Source: Rana Mitter, The Guardian , May 15 2011]

“The book is really two distinct narratives built into one. The first is a long-range sweep through Chinese history, from the very earliest days to the present. For the most part, this is elite history, where statesmen do deals with other statesmen... The historical merges into the personal in the early 1970s, when Kissinger, as national security adviser, becomes a central figure in the narrative during the secret approach to Mao's China. Inevitably, the sections many will turn to first are those where Kissinger reveals the details of his conversations with top Chinese leaders from Mao to Jiang Zemin. The contours of the story are familiar, but the judgments on figures who have passed into history still have freshness because they come from the last surviving top-level figure who was at the 1971 meeting.”

“One aspect of Chinese politics that Kissinger stresses is the tendency of leaders to make statements and let listeners draw their own inferences and that is a technique that he employs throughout the book. He notes that some observers consider Mao's cruelty a price worth paying for the restoration of China as a major power, whereas others believe that his crimes outweigh his contribution.”

“Nixon's role also comes in for scrutiny by his former secretary of state. Despite his fondness for "vagueness and ambiguity", among the 10 presidents whom Kissinger has known, Nixon "had a unique grasp of long-term international trends". It is hard not to see there yet another subtle criticism of more recent administrations which have failed to consider the impact of their policies in the longer term, particularly in the Middle East.”

“The final part of the book has a distinctly elegiac feel, as if Kissinger is worried that the rise of a new assertive nationalism in China along with "yellow peril" populist rhetoric in the US may undo the work that came from that secret visit to Beijing in 1971. His prescription — that the west should hold to its own values on questions of human rights while seeking to understand the historical context in which China has come to prominence — is sensible. But policymakers in Washington and Beijing seem less enthusiastic about nuance than their predecessors. The hints and aphorisms batted between Zhou and Kissinger have given way to a more zero-sum rhetoric.

Henry Kissinger will always remain a controversial historical figure. But this elegantly written and erudite book reminds us that on one of the biggest questions of the post-second world war world his judgment was right, and showed a long-term vision that few politicians of any country could match today. Unless, of course, Hillary Clinton is even now on a secret mission to Tehran.”

Martin Jacques on China

Mao-era foreign friends poster Martin Jacques, author of “When China Rules the World: the End of the Western World and the Birth of a New Global Order” wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Evert since the Nixon-Mao rapprochement ...there has been an overdue belief in the West that eventually China would become like us: that, for example, a market economy would lead to democratization and that a free media was inevitable. This hubristic outlook is deeply flawed.”

“The issue here is much deeper than Western-style democracy, a free media and human rights, China is simply not like the West and never will be. There has been an underlying assumption that the process of modernization would inevitably lead to Westernization; yet modernization is not just markets, competition and technology but history and culture. And Chinese history is very different from that of any Western nation-state....The West’s failure to understand the Chinese has repeatedly undermined its ability to anticipate their behavior.”

“The fundamental reason for our inability to accurately predict China’s future is our failure to understand its past. Although China has described itself as a nation-state for the last century, it is in essence a civilization-state. The longest continually existing polity in the world, it dates to 221 B.C. and the victory of the Qin. Unlike Western nation states, China’s sense of identity comes from its long history as a civilization-state.”

“The Chinese state enjoys a very different kinds of relationship with society compared with the Western state. It enjoys much greater natural authority, legitimacy and respect, even though not a single vote is cast for the government. The reason is that the state is seen by Chinese as the custodian and embodiment of their civilization. The duty of the state therefore lies deep in Chinese history. This is utterly different from how the state is seen in Western societies.”

Jacques wrote in the Times of London, “There are of examples of how China will remain different...Unlike in Europe, the state has never had its powers curbed by competitors, giving it an unrivaled position at the heart of Chinese society; or its highly distinctive position on race, where about 92 percent of the population believe that they are of one race; and the lack of conception of, or respect for, difference that flow from this...The rise of China will transform a world that presently conforms to a Western template.”

Jacques then goes ahead and paints a world in which China is dominant culturally and politically. He visualizes a world in which the yuan and Mandarin will replace the dollar and English as the world’s dominate currency and language; where Confucianism replaces Western philosophies as the underling pining of society; and where Chinese historical events, literature and film become known to everyone.

Jacques later wrote, “China is becoming a global power, while America no longer has the same authority that it used to have...The U.S. has only just begun to wake up to the fact that it is in decline...It is completely unprepared for what this might mean: that it can no loner deal with others in the way that is has, that it can no longer assume a relationship of superiority on its dealings with China , and that it has to seek a new understanding of China rather than expect the latter to continue to play second fiddle...relations between the two could steadily deteriorate with negative implications for the rest of the world.”

Tom Scocca of the Slate wrote in the Book Forum, “Jacques's project is to debunk the notion that economic development leads inexorably to liberal democracy and Westernization. China, Jacques writes, is modernizing on its own terms, following cultural habits and priorities laid down over thousands of years. Western leaders fail to grasp this because the West is unable to reckon with its own decline, which is well under way as China rises. “The most traumatic consequences of this process will be felt by the West because it is the West that will find its historic position being usurped by China,” Jacques writes.” [Source: Tom Scocca, Book Forum, November, 2009]

"China, in this account, is not a mere nation-state, as Europeans understand it, but a “civilization state,” with an abiding and transcendent sense of unity, a shared attitude of racial solidarity, and an overwhelming belief in its cultural superiority. Its imperial habits of power, refreshed by its colossal economic growth, will pull the countries around it back into their ancient role as submissive tributaries."

"His portrait of the workings of the Chinese regime — the way the central government has ceded power and control to its immense provinces — helps explain the country's capacity for absorbing contradictions, from the launch of capitalist development zones through the “two systems” takeover of Hong Kong to the mainland's tolerance of, and growing closeness to, Taiwan. His depiction of China's maneuverings to build a commercial and financial sphere of influence in Asia over the past decade conveys Western fecklessness and complacency."

Critique of Martin Jacques

Tom Scocca of the Slate wrote in Book Forum: “The book was in the works for more than ten years, through a period of almost incomprehensibly sweeping change in China, and it shows a certain strain from the effort of keeping up:Jacques's project is to debunk the notion that economic development leads inexorably to liberal democracy and Westernization — a theory that had a stronger grip on the world's imagination back in the late 1990s, when he started working on the subject.” [Source: Tom Scocca, Book Forum, November, 2009]

“Jacques's insistence that China not be viewed through a Western frame gives some parts of the book a pragmatic clarity...But China's complexity and capacity for paradox also mean that the more Jacques aims for big predictions and sweeping conclusions, the more the particulars get mangled...He swings back and forth between flatly saying China was colonized by the West and flatly saying it wasn't — both of which can be true, but without fuller context the author just seems absent-minded.”

“If anything, Jacques appears well acquainted with China and shows far less familiarity with the US. His account of the fading West seems overly influenced by the experience of his own native waning empire. The West is in thrall to rationality, he writes, and so cannot understand the deeply superstitious Chinese mind. Anyone who has lived in the land of angels, vaccine resisters, and the Prosperity Gospel might suppress a chuckle.”

“Still, all the theorizing, even when it's wrong, can inspire some productive countertheorizing. When Jacques predicts, for instance, that English as a global language may go the way of French and Latin, fading with its speakers' influence, it is one of the many moments where he seems to have forgotten the existence of India. And what if India's linguistic and cultural bonds with Britain and the United States prove to be important in the world to come?”

“But the most important countertheory to consider arises from Jacques's notion of unity as China's defining feature. As he notes, China has spent a great deal of its history disunited, waiting sometimes centuries for the next ruler to come along and pull it together again. This does show China's commitment to unity, but it also shows that the effort of governing a China-size China has historically been as much as any government can handle, and too much for many.”

“For China to conquer the world, the Communist technocrats will need to get past this historical limit — in the face of chronic and worsening drought, possible unrest among the losers in the economic transformation, the poisonous side effects of cramming the entire Industrial Revolution into a few decades, and a troubling surplus of male citizens thanks to the combined effect of sex bias and the one-child policy. These and other problems show no sign of bringing down the Communist regime, but they could certainly keep it busy at home.”

“In his less dramatic moments, Jacques is simply betting that, in the end, the West will become less important than it has previously been, which it will. He envisions a multipolar world to come, in which the old Euro-American “end of history” is reduced to one in a batch of different ways to be modern, and a vigorous, distinctively Chinese version of modernity becomes another.”

China's New Parochialism

Fareed Zakaria wrote: “The CEO of General Electric, Jeff Immelt, told the Financial Times in 2011 that it appeared that China did not want Western companies to succeed in that country anymore; he was voicing the feelings of many foreign CEOs. There is growing evidence in many areas that Beijing is favoring locals over Western companies, even violating the rules of market access and trade. The World Trade Organization ruled recently that China's regulations on foreign movies were a form of illegal protectionism and had to end. So far, Beijing has done nothing to abide by that ruling, though it is likely to expand its quotas to mollify the WTO. [Source: Fareed Zakaria, Fareed Zakaria.com July 14, 2011]

Countries play trade games all the time, but this is different. Over the past few years, a new Chinese parochialism has been gaining strength in the Communist Party. Best symbolized by the senior party leader, Bo Xilai, it includes a romantic revival of Maoism, harking back to a time when the Chinese were more unified and more isolated from the rest of the world. It is a reaction to the rampant marketization and Westernization of China over the past 10 years. Bo, who has organized mass rallies to sing old Maoist songs and routinely quotes Mao aphorisms, might well ascend to the Standing Committee of China's Politburo next year on the strength of this new populism.

After centuries of isolation, China has grown in power and strength because it opened itself to the world, learned from the West and allowed its industries and society to borrow from and compete against the world's best. It allowed for an ongoing modernization of its economic structures and possibly its political institutions as well. Its leaders Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin understood that this openness was key to China's success. A new generation of Chinese leaders might decide they have learned enough and that it is time to turn inward and celebrate China's unique ways. If that happens, the world will confront a very different China over the next few decades.

China and Its Image Abroad

Jeffrey Wasserstrom wrote “Yale Global Online, “China’s re-branding drive has depended on Beijing’s ability to take advantage of distinctively global aspects of the current era. Yet when this re-branding drive stumbles, as it has periodically in the two years since the Olympics, this too is often due to the special nature of the current period of globalization. [Source: Jeffrey Wasserstrom, Yale Global Online, October 10 2010, Wasserstrom is a professor of history at University of California Irvine and the author of “China in the 21st Century: What Everyone Needs to Know? (2011, Oxford University Press)]

The Nobel Peace Prize going to prisoner-of-conscience Liu Xiaobo, someone Beijing lobbied hard to keep from receiving the award, is the latest example of how difficult the Communist Party finds it in these robust global times to call the shots with international bodies. Back to the 2008 Olympics and its symbolism, all did not run smoothly, of course, from the Chinese government’s point of view. There were rough spots in even this most successful to date of all Chinese “soft power” spectacles. For example, the torch relay, the longest and most elaborate in Olympic history, was supposed to be a grand symbol of China’s reengagement with every part of the world.

In the end, though, only some stops outside of China went as planned. Protesters angered by Beijing’s policies toward Tibet and other issues held demonstrations, some rowdy, to mark the torch’s arrival in cities such as Paris. On the whole, though, domestic and foreign media reports tended to line up fairly neatly once the Games began. The main storyline was that, by successfully mounting such a grand show, China demonstrated howdramatically it had changed and that it was again a central player in world affairs.

Such a message was supposed to be carried forward by two subsequent events dubbed “Olympics” of a sort: the prestigious 2009 Frankfurt Book Fair, called an “Olympics for Literature” by Chinese media, and the 2010 Shanghai World Expo, often referred to in China as an “Economic Olympics” or “Olympics of Technology.” If all had gone according to plan, the Frankfurt fair would have generated domestic and international headlines trumpeting the growing profile of Chinese literature and increased respect for China’s cultural traditions.

Things began to go wrong for China a month or so before its October opening, when a seminar linked to the event was scheduled to take place including writers who have drawn Beijing’s ire. Poet and dissident-in-exile Bei Ling was among those invited to take part, and so was Dai Qing, the China-based environmental activist whose writings are banned from publication in the PRC. Beijing expressed displeasure at this lineup and called on German organizers of the session to pull invitations to the writers the government found objectionable. At first, fair representatives did an about-face and sought to placate the Chinese government by revoking the invitations, but in the end, the authors came and spoke. The result was a public-relations disaster, as the big story of the fair became Beijing’s ham-handed efforts to limit freedom of speech in an international venue and bully Germany — undermining in basic ways visions of the PRC 2.0 as a country that has become much less ideologically rigid and a more congenial participant in global affairs than was Mao’s China.

Flash forward one year, and we see a parallel situation — but with a higher profile in the international news. From Beijing’s point of view, October 2010 was supposed to be a month when the news coverage of the PRC dealt with upbeat topics such as China closing in on claiming record visitors for a World’s Fair — a record that currently stands at 64 million and is held by regional rival Japan for the Osaka 1970 Expo. Readers can find those stories about the Shanghai Expo, of course, but almost exclusively in the Chinese press. The biggest story internationally is Liu winning the Nobel Peace Prize, despite or perhaps partially because of Beijing pressuring the Norwegian committee in charge of the award to give it to someone — anyone — else. Beijing has claimed — in venues such as the Global Times, an English language paper linked to the Communist Party — that Liu’s win reflects anti-PRC “prejudice” and “extraordinary terror of China’s rise and the Chinese model” in the West. However well or badly this rhetoric plays to domestic audiences, to most foreigners it comes across as strident and paranoid and does nothing to help brand China as a modern country.

The road from the Opening Ceremonies of August 8, 2008, to this year’s Nobel Peace Prize award has not been smooth for Beijing’s re-branding drive. One common thread in the story of this campaign, though, is that both high points and low points involve global events and new technologies. After all, Liu is in prison not for a paper petition he helped draft and for which he collected signatures from people wielding pens. Rather he was given an 11 year sentence on charges of “subversion” for his role in Charter 08, a bold call for expanded civil liberties intended from the start to be distributed online, via the internet, a new media technology that censors in Beijing work overtime to control, especially at time likes this. Not long ago the same medium was dubbed “God’s gift to China” by an activist and writer once less known but now world famous — Liu Xiaobo.

China’s Increasing Belligerence

China’s hawkish military undid years of careful diplomacy in the last two years as it flexed its muscles in the South China Sea, harassing American naval vessels and alarming neighboring countries.

Many scholars and analysts say that China’s belligerence is the result of weak leadership at the top that has left many foreign policy decisions in the hands of the administration and members of the state security and propaganda arms.

See Japan, South Korea, Vietnam, Spratly Islands

Rana Foroohar, wrote in Time, “When leaders begin blaming "international hostile forces" for problems at home, it's a sure sign they've got trouble. That's exactly what Chinese President Hu Jintao did recently in a speech, published by a Communist Party magazine, in which he accused outsiders of plotting to "westernize and divide China." The hard-line rhetoric is likely aimed at diverting attention from a growing list of internal issues, including income inequality, unemployment and discontent over blatant land and money grabs by self-dealing state officials and developers. [Source: Rana Foroohar, Time, January 16, 2012]

Chinese Approach to Negotiations

Journalist and China expert James McGregor wrote in the Washington Post, “China is about unity, focus and leverage. Chinese officials and business executives are obsessed with a single question: What advantage do I have over you?”

Henry Kissinger wrote in Newsweek, "China' approach to policy is skeptical and prudent...impersonal, patient and aloof; the Middle Kingdom has a horror of appearing supplicant. Where Washington looks to good faith and good will as the lubricant of international relations, Beijing assumes that statesmen have done their homework, and will understand subtle indirections." The Chinese often "indicate a strong preference, not a condition....To the Chinese, Americans appear erratic and somewhat frivolous."

Beijing takes it time making decisions. Kissinger wrote: "The Chinese maneuver to induce their opposition to propose the Chinese preference so that Chinese acquiescence can appear as the granting of a boon to the interlocutor....When faced with what is considered a legacy of colonialism, China is prone to bully in order to demonstrate its imperviousness to pressure. Any hint of condescension or sign that Chinese territorial integrity is nor being taken seriously evokes strong — and to Americans, seeming excessive — reaction."

Many feel the best way to persuade Beijing is through quite, private pressure rather than through public upbraiding and humiliation. One Chinese scholar, who has written extensively about the United States, told Time, "If you treat China as a friend, he will treat you well and will never betray you. Treat him like an enemy and he'll fight back without hesitation."

Welcoming Foreign Leaders to China and Signing Ceremonies

When the leaders of China welcome leaders of other nations to China the visits often include a chat with with Chinese President Hu Jintao in front of a huge Chinese painting inside the Great Hall of the People, a 21 gun salute, a stroll before an honor guard and the signing of several deals. The Great Hall of the People meetings are shown repeatedly on Chinese television to reinforce Hu’s status.

“On his visit to China in 1984 with U.S. President Ronald, James Mann of the Los Angeles Times wrote,”We landed in Beijing, at the old airport, on one of those April days when it rains mud. The sky was a pale yellow-orange. The first stop was Tiananmen Square, where, in front of the Great Hall of the People, Reagan went to welcoming ceremonies: the girls waving bouquets and shouting “Huanying,” the 21-gun salute. Some in the White House press corps made a great deal of this reception, interpreting it as an Important Sign of China’s love for America or for Reagan or as an upturn in Sino-American relations. A day later, a reporter living in Beijing, perhaps from one of the wire services, told me the president of some Non-Superpower nation (was it Lesotho? Lichtenstein? Brunei?) had gotten virtually the identical welcoming ceremony, or a warmer one, in the same place the day before Reagan arrived.” [Source: James Mann, hkej.com, April 30, 2011]

On the deals that are signed, Murray King, managing director for Greater China at APCO Worldwide, a business advisory firm, told the Washington Post it is not unusual for Chinese leaders to race through with signing ceremonies for major business deals around the time of high-level foreign visits — and to have many of the deals never go through. A memorandum of understanding in China "is a first date," King said. "And not all first dates lead to marriage." Andy Klump, managing director of Clean Energy Associates, a solar advisory firm. "Typically, there's always a big bang and a lot of press when these agreements are signed, but they often don't come to fruition." [Source: Andrew Higgins, Washington Post , May 17, 2010]

Muddle Kingdom Has a Serious PR Problem

Isaac Stone Fish wrote in Foreign Policy, “Both domestically and internationally, the Chinese Communist Party has a public-relations problem: Its officials do not know how to communicate with the media. Decision making is highly centralized, and the relatively low-ranking officials tasked with speaking to reporters don't want to offend their superiors by saying the wrong thing. Although Reporters Without Borders ranks China's media as 174th in its latest Press Freedom Index, just slightly better than Iran and worse than Sudan, news is transmitted through Twitter-like micro-blogging services, of which roughly 250 million Chinese use. Though few expect China's stilted state-run media to be crusaders for change, there are more independent newspapers, like the business magazine Caixin and the newspaper the Southern Metropolis Daily, and journalists there increasingly ask difficult questions about everything from pollution cover-ups to low-level official corruption. [Source: Isaac Stone Fish, Foreign Policy, February 8, 2012]

Spokesmen, though, hide from the domestic and international press. [Except for one] all of the half-dozen current and former spokespeople I've met have declined to give me their contact information besides a general office phone number. Wringing a comment from a government ministry more often than not involves the request to fax a list of questions, which are rarely answered. And when poorly trained spokesmen and officials do speak, PR disasters often ensue.

After a high-speed train crashed in Wenzhou last year, killing 40 people, the railway ministry tried to clean up the accident before an official investigation could take place. The railways spokesman claimed, unconvincingly, that this was done to aid rescuers. He told reporters, "Whether you believe it or not, I believe it anyway." The ministry sacked the spokesmen, the fourth ministry official to be fired after the crash, but his remarks only added to public anger and added to grassroots pressure for the government to reform the ministry .

China faces a worse PR problem internationally. After the Nobel Committee awarded imprisoned dissident Liu Xiaobo the Peace Prize in 2010, China's Foreign Ministry spokesman called the decision "blasphemy," a response that immediately fueled comparisons between China's response and that of Nazi Germany, when the Nobel Committee awarded the prize to a German dissident. The Western world perceives the Chinese government as unreasonable toward the Tibetans in part because of its officials' tendency to issue tin-eared statements calling the Dalai Lama names like a "wolf in monk's robes."

Chinese government officials complain of an anti-Chinese bias in Western media , but the foreign journalists whose reporting shapes Chinese perception almost always have a difficult time getting the Chinese government's side of the story. Government officials and spokesmen rarely give interviews. Chinese dissidents are generally far more media savvy. The Dalai Lama has given hundreds of one-on-one interviews to foreign media. So has dissident artist Ai Weiwei. President Hu Jintao has given none. With the exception of Premier Wen Jiabao, for the past few years neither have any of the other members of the Standing Committee of the Politburo, ostensibly the nine most powerful men in the country.

Yiyi Lu, a former Chatham House fellow and expert on Chinese civil society, wrote a paper entitled "Challenges for China's International Communication," due to be published in April. She reports that China's bureaucratic system punish those who make mistakes when talking to journalists but doesn't reward those who say positive things, creating strong disincentive for officials to engage the media. In addition, "spokespersons dare not comment on officials who are more senior than them. Since most spokespersons are middle-ranking officials, it means many topics are off limits," she writes.

Things used to be much worse. One of the Communist Party's founding mandates was to "thoroughly break off connection of any kind with bourgeois intellectuals and similar parties.” and the country was closed to outsiders for much of the Mao years. China first appointed a spokesman for the Foreign Ministry in 1983 who held weekly press conferences but didn't allow questions; the second spokesman appeared in the Taiwan Affairs Office in 2000. After being slow to respond to successive PR disasters, like the SARS outbreak in 2003 and the Tibetan riots in 2008, the government has made it more of a priority to try to present its side of the story to the international media, but has yet to set up a functioning system of spokespeople.

But instead of focusing on domestic accountability or openness, the Chinese government has been investing heavily in the internationalization of its own TV and news stations, to counter what it perceives to be anti-Chinese bias in the Western media. The state broadcaster CCTV yesterday launched a new program in English called CCTV America, which it says will "project China" to the world. The central government has reportedly committed $6 billionto the global expansion of its state run media. But by allowing its spokesman and officials to actually say something and convincingly present their side of the story would go a long way to countering perceived media bias.

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2015