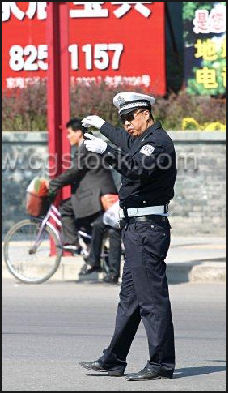

DIFFERENT KINDS OF POLICE IN CHINA

Traffic cop The main national police force in China is the People's Armed Police (PAP). While the People's Army has been reduced in size in recent years the People's Armed Police has been expanded, in many cases with former PLA soldiers, many of them trained in riot control. The rise of the PAP illustrates that the Chinese leadership in many ways is more concerned about domestic security than foreign threats.

The PAP was created in the 1980s to deal with domestic disturbances. It acts as riot police and guards government compounds and foreign embassies. It usually handles border defense but is called in sometimes to back up local police. It recent years it has been put to work suppressing anti-government protest of over land seizures, environmental problems, workers uprisings and other protests. The PAP has developed tactics that have allowed them to defuse tense situations without having to resort to violent crackdowns. Deng Xiaoping pointed out soon after the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown, the PLA and PAP were a "Great Wall of Steel" that safeguarded the CCP’s power and prerogatives.

The Public Security Service (PSB) is both a local police and the Chinese equivalent of the KGB. There are also paramilitary armed police and more than 1 million security guards in China. Police on the mainland and in Hong Kong have worked together to track down kidnap victims and break up a multi-million dollar loan sharking racket.

Quasi parapolice — known as "cheng guan" — operate in many places. Often little more than thugs, they are often hired by officials to help them carry out some unpopular actions such as collecting taxes and fines and ousting peasants from seized land. See Police Abuse Below

The 700,000-member People’s Armed Police is a paramilitary force whose duties include guarding embassies and putting down riots. It is commanded jointly by the Defense and Public Security ministries in close coordination with Communist Party leaders, in particular the leader in charge of security in the Politburo Standing Committee.

In December 2008, the Chinese government announced the creation of a new special unit aimed at cracking down on gun-related crimes and organized crime such as organized prostitution, gambling, drug production and trafficking.

See Separate Articles POLICE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com PROBLEMS WITH THE POLICE AND LAW ENFORCEMENT IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Chengguan

The chengguan (City Urban Administrative and Law Enforcement Bureau, also known as City Urban Administrative Enforcement Bureau in Chinese) have a notorious reputation, with many regarding them as little more than thugs. They are feared and despised for their capricious crackdowns and penchant for violence. They employed to deal with low-level crime and disorder and responsible for cracking down the street vendors, hawkers, and even the shoe shiners in the streets and are known harassing migrant workers, minorities and people they deem as suspicious, and detaining them is they lack the right residency permits.

“Chengguan are the thuggish city management officials who are supposed to keep order on the streets but who often end up abusing citizens, “David Pierson wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Think of them as thuggish meter maids or health inspectors with batons. Hardly a week goes by without a new controversy involving the municipal officers, a rung below the police, beating an unlicensed hawker or smashing a street vendor's stand. [Source: David Pierson, Los Angeles Times, July 07, 2011]

The chengguan have a reputation for brutality, which has made them widely reviled, and they have been involved in several deaths. In 2008, four enforcers beat a man to death after he had used his mobile phone to film a violent confrontation between villagers and officials. In another case, three officers were jailed for stabbing a noodle seller to death in a row over his stall. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, April 23, 2009]

"To many, the officers embody all that is wrong with authority figures in China: impunity, abuse of power and disproportionate targeting of the poor," Pierson wrote. "It's why a kebab cart owner who stabbed two chengguan to death in 2009 after they attacked him was largely heralded online as a vigilante hero. Victims of chengguan violence have included a watermelon peddler who was paralyzed and a construction company boss who was killed after he dared to film the chengguan trying to stop a protest. One chengguan showdown with street vendors set off a three-day riot involving thousands in Xintang that was sparked when chengguan reportedly beat a pregnant roadside stall owner.

Critics have often blamed poor training, pay and prospects for the lack of good recruits. But extracts from The “Practice of City Administrator Law Enforcement” “by the Beijing City Administration Bureau” explicitly advise them on using violence (See Law Enforcement Textbook Below).

plain-clothed police at Wangfujing Street in Beijing

Chengguan Versus Peddlers

David Pierson wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Unpermitted vendors, the primary target of the chengguan, have been omnipresent in China since migrant workers began pouring into cities. Residents turn to the hawkers for quick meals and cheap goods, and the vendors rely on the meager earnings to scratch out a living.In most cases, the chengguan don't appear to invoke their ability to fine and confiscate wares. Instead, most brushes play out like routine games of cat and mouse, with the feline appearing barely enthused. [Source: David Pierson, Los Angeles Times, July 07, 2011]

Such was the case on a recent afternoon in southwest Beijing, where clothing vendors were interrupted by shouts of "Chengguan! Chengguan!" Within seconds, many had packed up their merchandise and fled. One of them wasn't fast enough and was still there when a lanky officer surnamed Yan showed up and patted her on the shoulder."It's better you go home early and hang out with your family," he said. The vendor thanked him and peddled away. Asked why he let her go, Yan said, "I'm also human. It's hot and most of these people have to do this" to make a living. As for the merits of his profession, Yan said, "This is not an easy job. I won't let my son take the same job when he grows up."

Describing a typical incident involving the Chengguan, Sharon Lafraniere wrote in the New York Times, “More than 50 people gathered on a street corner. Officers had confiscated a motorcycle that was being repaired on the sidewalk instead of inside a shop, as regulations require. The bike’s owner was crying foul. A 15-minute standoff ensued before the officers, grim-faced, elbowed their way to their vehicles and sped off with the motorcycle and its owner. Li Xuedong, 40, a coordinator attached to the male squad, remained behind, his white badge flipped over to conceal his name.” he told the New York Times: “Sometimes we fight verbally. Sometimes we fight physically. Most of the time it is the public who starts it.” [Source: Sharon Lafraniere, New York Times, December 1, 2010]

police at Wangfujing Street in Beijing

Sympathy for Chengguan

David Pierson wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “In what might be one of toughest sells of the century in China, some are arguing that the chengguan are unfairly demonized and deserving of a little empathy. An essay spreading on Internet forums and purportedly written by an anonymous chengguan says his profession has been scorned to the point that he can't carry out his work. [Source: David Pierson, Los Angeles Times, July 07, 2011]

"Our job is to deal with society's most vulnerable citizens and squeeze them further; conflict is inevitable," writes the author, who says he earns $185 a month, about the same as a construction worker. But "the vulnerable are not necessarily innocent. The sympathy these illegal vendors get has, to some extent, made the vulnerable privileged while we chengguan have become the humblest of the humble."

The chengguan have faced a difficult task ever since they were established more than a decade ago to streamline the role played by myriad departments in enforcing municipal codes on ever more crowded streets. China Labor Bulletin, a nongovernmental organization based in Hong Kong that is known for its support of factory workers and laborers, issued a translation of the essay and a commentary, reasoning that there would be less conflict if chengguan were better trained and paid. Though the essay could not be verified, the organization noted that its details were consistent with past reports.

"Chengguan have a uniform but no real power," China Labor Bulletin said. "They are supposed to enforce about 300 legal articles and regulations, but are given no specific instruction on how to enforce them. The only sanctions they have are fines and confiscations. However, these are precisely the penalties that are most likely to trigger a violent confrontation because, for impoverished street vendors, a fine or confiscation of their property means a loss of income and in many cases is a direct threat to their livelihood."

Chengguan, Victims of Violence and Efforts to Improve Their Image

David Pierson wrote in the Los Angeles Times Aware of their bad PR, many departments have tried image makeovers by hiring more female officers. Others have opened micro-blog accounts to appear more accessible. And to avoid scuffles, officers in Wuhan resorted to surrounding illegal hawkers and staring at them until they packed up and left (a far less controversial tactic than the directive to "leave no blood on the face, no wounds on the body, and no people in the vicinity, when dealing with suspects" that was advocated in a chengguan training manual that surfaced in 2009). [Source: David Pierson, Los Angeles Times, July 07, 2011]

Among the indignities was watching a colleague getting kicked in the groin by a shopkeeper, having a vendor pretend to lay dead on the ground while his son threatened to post a video, and riding to work in a rickety $300 minivan pulled from the scrap heap.

In some cases, the chengguan are themselves the target of violence and retribution. In July 2011near the city of Wuhan, a chengguan supervisor was bloodied with batons by private security guards after he and fellow officers tried to confiscate chairs and tables blocking traffic. Chengguan in the factory town of Shenzhen were issued armored vests after a colleague was fatally stabbed by a peddler in April.

Jiwei

The top corruption fighter in China the Communist Party’s Central Commission for Disciplinary Inspection (CCDI). In each province, city and county, CCDI at staff at different levels are empowered to investigate corruption cases. For example, a provincial commission can investigate prefecture-level officials, and so on. The CCDI are referred to as jiwei in Putonghua. [Source: Wu Zhong, Asian Times, June 9, 2010]

“Jiwei at all levels are not law-enforcement organs - they are more powerful. A jiwei can summon any party or government official under its jurisdiction for questioning and have him or her immediately put under house arrest for investigation. The process is known as shuan'gui. No time limit is set for shuan'gui - an official can be held for as long as is necessary. When enough evidence is found, the official is handed over to the public prosecutor. Before his conviction in 2008 for graft, former Shanghai party secretary Chen Liangyu was held in shuan'gui for over a year.”

“Shuan'gui is not stipulated in the constitution or any law, and can be authorized without judicial involvement or oversight, leading to criticism from legal experts. But from the CCP's point of view, the party is entitled to whatever steps it needs to keep its own house in order. In China, almost all officials are party members subject to party discipline before they are prosecuted by the law. Also, according to unwritten rules, party members cannot stand trial unless their membership has first been revoked - to save the ruling party embarrassment.”

“The premise that the party polices itself with jiwei seems appropriate for a nation taking on “CCP characteristics”. While official corruption appears rampant in China, without jiwei and unconventional methods, it may have run out of control. There is a saying in Chinese officialdom: “Powerful officials fear nothing but a knock on their doors by jiwei”.”

“In recent years, President Hu Jintao has further expanded the power of jiwei by making their upper-level clearance a prerequisite for an official's promotion. In essence, jiwei now also hold the political careers of party and government officials in their hands.

Fake Jiwei

“This fear of jiwei was recently illustrated by a case in Chongqing, southwest China. The drama unfolded in March while a sweeping crackdown on gangsters and corrupt officials ordered by party secretary Bo Xilai was underway. As reported by the Chongqing Morning News, three men walked into the office of a district bureau director. One of them waved what seemed to be jiwei identification - a tiny booklet with a blue plastic cover, and said, “We were tipped off that you've been taking bribes. Come with us immediately.” [Source: Wu Zhong, Asian Times, June 9, 2010]

“Unnerved, the director hurriedly offered seats and cigarettes to the men, forgetting to check their IDs. But the impatient trio ordered him to leave immediately - and the official obeyed. Two men grabbed his arms and shoved him out of the office building. No one dared intervene. The official was then driven to an unknown location for shuan'gui. Cooperative from the start, the director made a “full confession”, even divulging the pin (personal identification) number of a bank account which had 140,000 yuan (US$20,500) in it. The three men quickly withdrew the funds.”

“The official then told his captors about another bank account with 700,000 yuan in it and the men took him back to his office to retrieve the card. But by now, the official was beginning to suspect something. Since real jiwei would never withdraw money from a suspect's account that could be used as evidence, the official shouted for help in his office. The men were quickly apprehended. It turned out that the fearsome jiwei were three unemployed, uneducated imposters.”

“During their police interrogation, the suspects confessed that they had taken inspiration for the crime and learned to act like real jiwei from anti-graft movies. The crime happened amid Xi's “Strike Hard” crackdown, so the three were quickly prosecuted with the mastermind receiving nine years in jail and the other two seven years each.”

“The Chongqing Morning News article received plenty of attention, and media commentators and netizens began to complain that it had omitted details. Why did the three men choose that particular official? Was it random or did they know something about him? What happened to the official involved?”

Young and Pretty City Wardens in Chengdu

Sharon Lafraniere wrote in the New York Times: “More than one government has tried to brush up the image of China’s urban inspectors. One city mandated that all new recruits have a college degree. Guangdong Province changed the gray-green uniforms to a supposedly more inviting blue. Wuhan, in central China, substituted stare-downs for strong-arming: in 2009, one report stated, 50 officers encircled a wayward snack cart, glowering steadily for a half-hour until the peddler packed up and left.” [Source: Sharon Lafraniere, New York Times, December 1, 2010]

Xindu, an urban district of 680,000 in Chengdu, has chosen to soften its image with 13 women, specifically chosen for their looks, shapeliness and youth. Tania Branigan wrote in The Guardian, “Authorities in Chengdu...have said they will hire only attractive young women for the law enforcement jobs, hoping it will improve their district's image. The Xindu district government's advertisement stipulates that candidates must be female, aged between 18 and 23, over 5ft 2in (1.6m) tall, attractive and with a good temperament. Their contracts will end when they turn 26.” [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, October 28 2010]

The human resources director of the law enforcement bureau in Xindu told The Guardian “their main job is to present a good image so they have to be good looking...And when they get older, they will get married and have children so it will not be convenient for them to do such work. Having them leave at 26 is for their sake." He insisted it was unfair to describe them as "flower vases" — a Chinese idiom for women who are decorative but of little use. "They need a good temper and communication skills as well," he told a Chengdu news website

Lu Ying, former director of the Gender center at Sun Yat-sen University, said it was common for employers to pick out female candidates because they were prettier. "The effect of looks discrimination is much bigger for women than men. What makes it worse is that for women, the job opportunities are less than for men already," she said. "It is a very bad phenomenon. It is much worse when a government body does this because it will set a terrible example." [Source: Sharon Lafraniere, New York Times, December 1, 2010]

Sharon Lafraniere wrote in the New York Times, “After the district advertised for eight new female recruits in October, an editorial in The Beijing Evening News questioned whether the women had actual duties or were simply scenic diversions. The answer appears to be a little of both. “Their image is the important thing,” one unnamed district official told Rednet.com, a quasi-governmental Web site. “First, the candidates’ external qualities will determine if they make the cut, such as height, weight, facial features, etc.” Next comes temperament and “inner qualities.”

Zheng Lihua, the deputy director of the district’s city management bureau, is not eager to endorse that description. But he told New York Times that height requirements were standard in many Chinese job advertisements for both sexes. So is the demand for orderly facial features. Whether that means good-looking is a matter of debate among Chinese. Certainly, the disabled or disfigured need not apply. “We can’t let a lame person or a hunchback come to serve here,” Mr. Zheng said. “His image would not be good.”

Describing the training of the new female recruits, Sharon Lafraniere wrote in the New York Times, “Like an urban drill sergeant, Tang Shenbin paced on a city square, sternly inspecting his nervous charges, issuing soft voice commands with military authority. He wanted the female members of chengguan....to convey a certain impression to a clutch of onlookers... “Stand straight! Look sharp!” Show them, he whispered, “what pretty girls are like!”... Four barely-past-teenage girls in white gloves and identical olive jackets and pants snapped to attention. Four pairs of black pumps lined up ruler-straight. Four prim hats perched perfectly atop hair bound in blue and white striped bows...”Personally, I think they are average-looking,” Mr. Tang said, dismissively. “Models are pretty.” [Source: Sharon Lafraniere, New York Times, December 1, 2010]

Young and Pretty City Chengdu Wardens at Work

Unlike the police, the young girls are wardens’ officers who are authorized only to enforce city ordinances by imposing fines and other administrative penalties. Describing a couple of them at work, Sharon Lafraniere wrote in the New York Times: “Liu Yi, who patrols the Baoguang Square near a monastery, is 22, apple-cheeked with a finely curved mouth. She does not consider the stress on her appearance to be sexist, she said. “Do you think I look sexy in this uniform?” she asked with a wry look. Said her dimpled co-worker, 21-year-old Xu Yang, “Our job is to present the city’s image.” [Source: Sharon Lafraniere, New York Times, December 1, 2010]

“They do not object to their limited tenure either, they said, because they harbor career ambitions greater than simply shooing vendors into the alleyways where they are supposed to confine their business. Every morning, the squad faces off against a dozen or so peddlers who dart around on foot or bicycle, trying to sell as many buns or bowls of tofu as possible before they are run off. “Master Wang, you have to leave. We have told you many times!” said Ms. Xu as one vendor fled on foot, temporarily deserting his bicycle-drawn cart of noodle-fixings.”

The officers describe their duties as more monotonous than strenuous. “It is pretty much the same every day,” said Huang Jing, 20, who studies marketing in her off hours. “Very routine.” One reason is that female officers lack the power of their male counterparts to confiscate vendors’ goods. They can only threaten to report violators to their male supervisors. That tends to shield them from the sudden public displays of animosity against officialdom that are common throughout China...Retirement at age 26 is mandatory. Officials said the job was physically too arduous for women over 25.”

Private Security

Some security guards have a reputation for being thugs and beating up on people that cross them. Many have no training. Some have ties with organized crime groups. Some are members of organization run by local police. Others are used by their employers as heavies to break up protests and collect money that is owed them.

Attention was brought to the private security issue in 2009 when a journalist investigating a tip of a woman’s murder was beat up so badly by security guards he had to be hospitalized. The journalist said he was beaten for more then 10 minutes, resulting in severe neck and abdomen injuries. Photos showed massive bruises on his arms and neck.

Top levels of security guards are known as “bao an”, or those who “preserve the peace.” They are required to undergo 240 hours of training before getting a license.

There are many stories of migrant factory workers being shaken down, beaten and even killed by brutal auxiliary police.

Vigilante Justice in China

Private detectives and independent police often work harder and have better success than the police.. One man dubbed by "Zorro" by the Chinese press wears a uniform even though he is not officially a policeman. He works independently to retrieve women who have kidnaped and sold as wives. He rescued 100 women between 1992 and 2000.

See Wild Yak Brigade, Nature, Tibet.

In affluent cities such as Shenzhen it is becoming increasingly common for rich people worried about kidnaping, robberies and assaults to hire kung fu experts as bodyguards.

“Hei shehui” (“black society thugs”) are hired by police to hand out extralegal punishment. A lawyer who endured a attack by these thugs said 10 men showed up in his office, threw a bag over his head, pushed him into the back of a car and took him to the basement of a house, where he was beaten and shocked with an electric prod for four hours and then driven to a forest and thrown from the car.

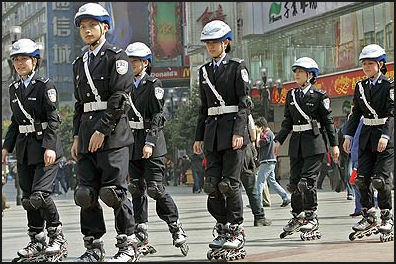

Police on roller blades

Detectives in China

The first detective agencies to open since 1949 opened during the early Deng era in the 1980s. Detective work is a growing business. As of 2004, China has 20,000 private detective agencies. Detectives are mainly involved in chasing owed money and finding lost relatives and friends. Some work for foreign companies, investigating fraud, doing background checks on Chinese partners and even raiding factories that produce counterfeit goods. Others are used to investigate corruption. Officially all detective agencies are illegal. In 2004 there was some discussion of making them legal.

Many detectives are hired to check on spouses and lovers suspected of having affairs. Some of the most well-known ones use trick they learned in the secret police and Hollywood movies such as using networks of informants, laying traps and setting up stakeouts. Some charge as much as $1,000 an hour.

One detective was called in by an American insurance company to investigate families accused of making false claims that members were dead. In some cases the detective solved the case by calling up the suspected family and having the “dead” person come to the phone. One well known detective warns judges that if they don’t accept their evidence he will investigate the judge.

Image Sources: 1, 3) Defense Talk; 2) Cgstock http://www.cgstock.com/china ; 4) Weird News; 5) Blogcadre; 6) Julie Chao ; 7) Xinhua ; others Wikicommons ; deGenerate films

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2012