HUMAN RIGHTS IN CHINA

China has been accused of using torture and arbitrary detention and denying people basic freedoms of speech, press and religion. Suspicion and fear of the government and military run high in China. Human Rights Watch has described China as a “highly repressive” state. Princeton University professor and Nobel laureate Paul Krugman called China a “rogue economic power” for being averse to complying with internationally-accepted rules.

China has been accused of using torture and arbitrary detention and denying people basic freedoms of speech, press and religion. Suspicion and fear of the government and military run high in China. Human Rights Watch has described China as a “highly repressive” state. Princeton University professor and Nobel laureate Paul Krugman called China a “rogue economic power” for being averse to complying with internationally-accepted rules.

In March 2008, the United States State Department removed China from its list of the 10 worst human rights violators. It did so just before the Tibetan uprising. A report said that China’s “overall human rights record remained poor,” the government increasingly harasses people thought to be a threat to the state and abuses found in China included “extrajudicial killings, torture and coerced confessions of prisoners and the use of forced labor.” The State Department didn’t say why China was removed from the list.

In April 2008, Amnesty International issued a statement that China’s human rights abuses were getting worse because of, not despite, the upcoming Olympics in Beijing. If anything the government is cracking down on dissenters harder than ever. A total of 742 people were arrested in 2007 for political crimes like subversion, according the San Francisco-based Dui Hua Foundation. This was the highest number in eight years and more than double the number than in 2005.

In many ways its hard to get a sense of what ordinary Chinese think about human rights issues. The government doesn’t allow polls or surveys on the issue to be taken. One man in Guangzhou told the New York Times, “Everyone here talks about social stability, but its only on the surface. In fact, the things we really feel, we can’t say.”

China human rights policy has been described as a series of freezes and thaws in which the media is muzzled and dissidents are detained during the freeze periods and dissidents are released and the media is given more freedoms in the thaw periods. The thaw periods often occur when China wants to put on a good face for the international community. Western leaders often make strong pronouncements about human rights when they are on their home soil but back off when the visit Beijing and are often most interested in trying to sell Beijing products from their countries

Articles on HUMAN RIGHTS AND DISSIDENTS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Amnesty International amnesty.org ; Human Rights Watch hrw.org ; Chinese Government Position on Human Rights China.org ; United States State Department Report www.state.gov ; Wikipedia List of Chinese Dissidents Wikipedia

U.S. Criticism of China’s Human Rights Policy

worker protest

In it annual human rights report released in April 2011, the U.S. State Department said China's human rights record is on a 'negative trend' with growing restrictions on freedom of speech and “severe repression' in its restive Tibet and Xinjiang regions. The U.S. report also criticized China over a severe crackdown on government critics involved with the so-called “Jasmine revolution.”

"A negative trend in key areas of the country's human rights record continued," the report said. "The government took additional steps to rein in civil society, particularly organizations and individuals involved in rights advocacy and public interest issues, and increased attempts to limit freedom of speech and to control the press, the Internet and Internet access," it said. The report said that Chinese authorities stepped up efforts "to silence political activists and public interest lawyers" last year, including by placing family members under house arrest.

China’s Criticism of the U.S.’s Human Rights Policy

In April 2011 Chinese report that came out in response to a U.S. report criticising China's human rights record the Chinese make note of the bloodshed of U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, reports of waterboarding and other harsh treatment of US enemy combatants, and said the American political system was in thrall to moneyed interests. “The United States has turned a blind eye to its own terrible human rights situation and seldom mentions it,” said the report, which is issued each year to rebut an annual US State Department report on human rights around the world.

The Chinese report sought called on 'the United States to face up to its own human rights issues.” It characterized U.S. society as a place where crime is rampant, police torture prevalent, and gun ownership out of control. 'In the United States, the violation of citizens' civil and political rights by the government is severe,' it said.

China Defends Its Human Rights Record

China takes a lot of heat on international level for its human rights record. Commenting on how much he talked about human rights during a visit to the United States, Chinese Prime Minister Zhu Rongji, said "I practically have blisters in my mouth."

China has been trying to improve its human rights record in recent years. It signed an important human rights treaty in October 1998 and ratified another one in March 2001. In December 2002, China invited United Nations investigators to study torture, religious freedom and arbitrary detention in China.

China’s defense of its human rights record typically involves criticizing the humans rights record of its critics. Zhu Muzhi, the president of the Communist-financed China Society for Human Rights Studies and a "master of the sound bite" according to the New York Times, said, "I certainly think America is not perfect when it comes to human rights. I do not think you have gotten rid of racial discrimination or segregation. the Los Angeles riots are a case in point." He also adds "Tremendous progress has been made in human rights. If you look at China's history, this is the best period in our history."

In a speech in April 2006, Chinese Prime Minister Wen Jiabao defended China’s human rights record saying, “People are enjoying way more freedom and rights in choosing their jobs, moving their homes, traveling to other countries as tourists and choosing their information” and said lifting 200 million out of poverty was “the biggest progress we have made.” As for criticism from the United States, he he accused Americans of turning a blind eye to its “own human rights violations” while “pretending to be the world’s judge of human rights.”

Human rights groups such as Amnesty International are regarded as overly hostile and aggressive by the Chinese government. John Kamm, president of Hong Kong’s American Chamber of Commerce and regional vice president of Occidental Chemical Company, has had great success pressuring the Chinese government to release political prisoners. He has convinced Chinese officials it is in their interest to let the prisoners go to it bolster China’s image abroad. He has said the key to his success has been “being patient, doing your homework and following through.”

The French scholar Francois Julien said that the words liberty, truth and rights are found in the Chinese language but they do not have the same meanings as they do in the West, where they descended from Greek and Christian philosophy. Julain said, “China thinks in terms of situation and process, not of identity and eternity, which are the basis of our idea of truth.” Julain also said the Chinese tend to see things in terms of influence, regulation and accommodation rather than right and wrong.

A foreign ministry spokesman in 2008 said, “I believe everyone knows that Human Rights Watch has some problem with its sight. It is biased. It has some problems with its eyes. It has weakness on seeing things properly.”

Jasmine "Protest" in February 2011 on Wangfujing Street in Beijing

Chinese Constitution and Human Rights

Han Dayuan, dean of Renmin University of China Law School, wrote in Legal Daily: The constitution is the founding law of the state. It carries supreme legal force and occupies the “leading” position in the socialist legal system wherein all laws and regulations should remain in accord with the constitution. This is why the majority of laws all say in their first articles: “This law is enacted in accordance with the constitution.” In his 2004 speech in Beijing commemorating the 50th anniversary of the establishment of the NPC, General Secretary Hu Jintao emphasized that to rule the country in accordance with the law means first ruling the country in accordance with the constitution and that to govern in accordance with the law means first governing in accordance with the constitution. [Source: Han Dayuan, Legal Daily February 15, 2012]

In 2004, China’s constitution was revised and “the state respects and safeguards human rights” was solemnly added to establish a national value system and set a basic standard for all acts of public authority. As a basic law meting out the specifics of the constitution, the Criminal Protection Law) CPL must obey the values of the constitution and give expression in its conception of values to the principles and spirit of the constitution, as well as establish institutions that respect and implement the provisions of the constitution. The relationship between the CPL and human rights is especially close, with the CPL having been called the “defendant’s charter of rights.” It should embody the requirements of the constitution and clearly provide for “protecting human rights.”

After the constitution was revised in 2004, the enactment and revision of laws must fully reflect the principle of protecting human rights.An important function of the CPL is to use procedural [norms] to safeguard the basic rights of specific groups. Generally speaking, in the procedures of the CPL, those who are being prosecuted are clearly in the weaker category. Their human rights are easily infringed upon by the mighty power of state organs, and so they rightly ought to receive fuller protection under the CPL in order to realize the principle of all being equal before the law.

China has already acceded to several international treaties related to criminal justice and has signed the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

Human Rights, Protecting the People and Revising the Criminal Procedure Law

According to a report by the Dui Hua Foundation: “Ever since the full text of a draft of the Criminal Procedure Law (CPL) revision was made public in August 2011, its content has been examined closely and debated vociferously within China. Supporters herald the legislation as a major improvement in the protection of rights, pointing to things like facilitating the work of criminal defense lawyers , formalizing procedures aimed at excluding evidence obtained illegally, and establishing new procedures for juvenile offenders . Critics, on the other hand, have raised concerns that the revision would greatly expand the power of investigators to abuse secret surveillance and to detain people without notifying their family. [Source: The Dui Hua Foundation, February 2012]

More than 80,000 recommendations regarding the draft amended CPL were submitted to the National People’s Congress (NPC) Standing Committee during a one-month period of public consultation that ended September 30. At least some of these suggestions made their way into a second draft that was reviewed by the NPC Standing Committee in late December. In March a final draft of the legislation was reviewed by the nearly 3,000-member NPC, where amendments — such as those pertaining to prohibition on compulsory self-incrimination, and emphasizing the basic principle of protecting human rights — were deliberated. The number of articles that the draft adds or revises makes up around half of the total number of articles in the current CPL.

Most of the discussion surrounding CPL revision concerned specific changes to procedures or measures added to the legislation. But there was also many concerns about changes that haven’t been made. For example, the drafts reviewed by the NPC Standing Committee do not change Article 1, the statement of the legislation’s purpose: “ ”[to protect the people]. Incommentary published in Legal Daily, Han Dayuan recommends changing that purpose to “[to protect human rights]. This change was included in each of the major revision proposals prepared by Chinese legal scholars after CPL revision was first placed on the legislative agenda back in 2003.

Han believes the change would better reflect the spirit of China’s constitution — which was amended in 2004 to affirm the state’s role in respecting and safeguarding human rights — and highlight both domestically and internationally China’s existing achievements and future goals with regard to rights protection and rule-of-law development.

The change is also significant because in the Marxist-Leninist-Maoist political culture of China, all references to “the people” are implicitly exclusive of particular groups, e.g., the exploiting classes, counterrevolutionaries, and “enemies of the people.” Removing this political category from the CPL would imply that the rights and protections granted therein are universal, rather than selective.

Making the protection of human rights the explicit aim of the CPL would thus strike a symbolic blow against the kind of “dual track” criminal justice system that is being fostered in China, one in which procedural protections are extended in the majority of criminal cases but withheld in cases deemed threatening to sociopolitical order.

China’s 2009 Human Rights Plan

In April 2009, China’s cabinet released on Monday what it called the country’s first national human rights action plan, a lengthy document promising better protection of a wide range of civil liberties enshrined in the Constitution but often neglected and sometimes systematically violated. [Source: Keith Bradsher, New York Times, April 14, 2009]

“The two-year plan promises the right to a fair trial, the right to participate in government decisions and the right to learn about and question government policies,” Keith Bradsher wrote in the New York Times. “It calls for measures to discourage torture, such as requiring interrogation rooms to be designed to physically separate interrogators from the accused, and for measures to protect detainees from other abuse, from inadequate sanitation to the denial of medical care. There are also specific protections for children, women, senior citizens, ethnic minorities and people with disabilities.”

“Human rights activists applauded Beijing officials for showing an interest in the issue. But they cautioned that any implementation would require years of work by local, provincial and national government agencies, many of which have shown little interest in initiatives that may limit their power.”

“Jerome Cohen, a New York University law professor who specializes in China’s legal system, said that the action plan was the result of growing worries in the Chinese leadership about public dissatisfaction with security forces and even outright hostility to police officers...The release of the plan by the Information Office of China’s State Council,or cabinet, suggests that the plan is designed partly with public relations in mind, Cohen said. But if widely circulated in China — and the report received considerable attention in the Chinese state-run media on Monday — it could contribute to changes.”

The impetus to create the document came in part from public support for a man who attacked a police station and killed six officers in revenge for what the man described as a beating at the station. The police denied any beating and the man, Yang Jia, who was executed in November 2008. Two days later, the Communist Party Politburo met to discuss ways to improve the public standing of law enforcement officers, part of a continuing effort that helped lead to the plan released Monday, Cohen said.

Xinhua, the official news agency, has said the government has admitted that “China has a long road ahead in its efforts to improve its human rights situation.”

Details of China’s 2009 Human Rights Plan

The 54-page “National Human Rights Action Plan of China 2009-2010 is divided into five sections: 1) Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; 2) Civil and Political Rights; 3) Rights and Interests of Ethnic Minorities, Women, Children, Elderly People and the Disabled; 4) Education in Human Rights; and 5) Performing International Human Rights Duties, and Conducting Exchanges and Cooperation in the Field of International Human Rights.

“The National Human Rights Action Plan of China 2009-2010 emphasizes economic and social rights instead, such as a right of urban and rural residents to a basic standard of living.” [Source: Keith Bradsher, New York Times, April 14, 2009]

“The document does not phase out China’s extensive and controversial system of administrative detention, which gives broad powers to local law enforcement officials, including the ability to send people to prison camps for re-education through labor without a trial. While the document guarantees a wide range of rights to detainees and petitioners, there is no promise to close the unregistered jails set up by municipal and provincial governments to detain petitioners who want to present grievances to higher levels of government.”

“The plan does call for China to go considerably further in areas where it has begun making changes, such as in releasing more information about government decision-making, and to extend to the countryside policies that so far have mainly benefited cities.”

“Governments at town and township levels shall make public the implementation of relevant state policies regarding rural work, their revenue and expenditure and their use of various kinds of special funds, the plan said.”

“While the plan calls for public opinion to play a larger role in decisions, the document does not set out any specific goals for turning China into a democracy in which the people have a say in choosing their country’s leaders.”

Freedom in China

Freedom and human rights for most Chinese has improved. Chinese are able to speak out more freely than they used on a number of issues and are exposed to more information and are more knowledgeable about the world than they use to be. Perceptions on freedom in China have a lot to do with one experiences. An elderly woman who lived through the Japanese occupation and the Mao era told the Washington Post, “I think these days we’re very free. In Mao’s time you just could not say certain things.” She then went on to say there was too much freedom for young people.

An independent historian and former political prisoner said that Tiananmen Square changed things. Before 1959, he said, “If you didn’t pay attention to politics you couldn’t survive.” Afterwards “people all turned to making money, seeking their individual benefits and interests.”

A journalist who was affected deeply by Tiananmen Square told the Washington Post, “I believe that freedom without democracy is fake freedom. There should be free speech, freedom to publish, a right to march, assemble and organize. Although these freedom are in the constitution, they cannot be realized in reality.”

A migrant worker told the Washington Post, “I feel quite free now. The ocean is wide enough for fish to jump and the sky is big enough for birds to fly...freedom is to be free physically. If you haven’t experienced what I have, you don’t know what freedom is.”

A salesman and Communist Party member, “Freedom means people can did whatever they want if only they don’t break the law...If you have a dream and work hard for it, you can get a good life. The country has become better and stronger. This cannot be separated from our individual efforts and striving.”

A university student majoring in French said, “I am not very interested in democracy or something like that. It’s not that I disagree with democracy, it has its advantages. But I think it’s unrealistic for China.” She recognized the progress China had made, saying, “More than ten years ago there would have been no way for me to sit here and discuss such a topic with you.” A first year middle school student, “In my eyes freedom means that parents don’t force me to do something I don’t want to do.”

Charter 08 Parade in Hong Kong

Charter 08

Charter 08 is a pro-democracy manifesto released online in December 2008 that among other things: 1) calls for a new constitution that guarantees human rights and open elections of public officials; 2) brings greater freedoms and democracy in China; 3) getting rid of the subversion laws; and 4) seeks an end to one-party rule.

More than 10,000 people, including some of China’s top intellectuals signed it despite efforts by the government to block it and punish its authors but news black outs and Internet censorship kept most Chinese from becoming aware of it.

Modeled after Czechoslovakia’s Charter 77, which was put together by scholars in that country in 1977, 12 years before the fall of Communism there, Charter 08 calls for a complete overhaul of the Chinese system and the introduction of true freedoms of speech and religion and independent courts. It states: “For China the path that leads out of our current predicament is to divest ourselves of the authoritarian notion of reliance on an “enlightened overlord” or an “honest official” and to instead move toward a system of liberties, democracy and the rule of law.”

Charter 08 also states: “Freedom is at the core of universal human values. Freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, freedom of association, freedom of where to live and the freedoms to strike, to demonstrate and to protest, among others, are the forms that freedom takes. Without freedom China will always remain far from the civilized ideals.”

Charter 08 was sent to people from all walks of life through e-mail mainly by people who supported it sending it to their friends and contacts. One 30-something cosmetology students that signed it told the Washington Post, “I was afraid but I had already signed it hundreds of times in my heart...If me, a little frightened person signed it them maybe others will feel inspired.”

Xiao Qinag, an adjunct professor of journalism at Berkeley, told the Washington Post, “This is the first time that anyone other than the Communist Party has put in written form in a public documents a political vision for China. It’s dangerous to be associated with dissidents so in the past, other ordinary people have not signed such documents. But ths time it was different. It has become a citizens movement.”

The effort was given a severe blow in December 2009, when Liu Xiaobo, one of the drafters of Charter 08, was given an 11-year prison sentence on subversion charges in what see a warning to anyone who dares to challenge the ruling regime.

See Separate Article on Chapter 08

Arbitrary Detainment in China

Amnesty International estimates a half million people are detained without charges in China. According to Amnesty International there are currently about 2,000 people in Chinese jails for political crimes and 230,000 people are in prison or labor camps who have not been charged of a crime. Thousands of Tibetan monks and nuns have been arbitrarily detained. China carried out more arrests and indictments for endangering state security in 2008 and 2009 than it did for the five year period between 2003 and 2007 according to the Dui Hua Foundation.

An unpopular law that allowed police to detain people traveling without resident permits was changed in the mid 2000s after a person detained under the law was beaten to death. The law was widely abused by police who would often detain migrants and hold them until a bribe was paid.

Attention was focused on detainment laws was also raised when the three-year-old daughter of a woman detained for shoplifting starved to death in her apartment while the woman was in prison. Once a man was illegally detained for 10 years because police could not gather enough evidence to convict him in court.

When Beijing is criticized about its detainment rules by the United States, the Chinese point out that hundreds of terrorist suspects have been detained without trial at Guantanamo Bay.

See Separate Article on Secret Detention Powers and Problems with the Chinese Legal System

Black Jails

In 2008, there was report that citizens in the city of Xintain on Shandong Province who tried to petition the government were locked up in mental hospitals to keep them from airing their complaints about local injustices. Some of the detainees were reportedly drugged.

Sometimes petitioners are thrown into “black jails,” illegal detention centers, to shut them up or keep them from filing their petitions. One 59-year-old woman, whose nephew was arrested, told the Los Angeles Times she was nabbed and placed in an isolated stockroom and held for days with about 100 others and finally released with her ailing husband and then abducted again and held for several weeks in a dilapidated private home. [Source: John Glionna, Los Angeles Times, January 2010]

Humans Rights Watch has released a 51-page report on he issue call “An Alleyway in Hell: China’s Abusive Black Jails”. It cites beatings, rapes, intimidation and extortion that have taken places at them. One victim was quote in the report as saying, at the place he was sent there were “locked steel doors ad windows. We never left our rooms to eat. We were given our meals through a small window space.”

Attention to the issue was raised in December 2009 when a guard at a black jail was sentenced to eight years in prison for raping a detained college student. Nicholas Bequelin, a senior Asia researcher at Human Rights Watch, told the Los Angeles Times, “As China tries to build a functioning legal system, this gnawing black hole for human rights grows right there.”

The Communist Party initially denied the jail existed but then acknowledged them in an article in the Outlook, which is owned by the official New China News Agency, saying there were at least 73 black jails in the Beijing area alone and an estimated 10,000 people have been detained in hundred of jails at one time.

According to the Los Angeles Times and Human Rights Watch the jails reportedly came into existence a few years ago after the government abolished another system that allowed officials to jail petitioners they considered a threat. Under the for-profit system private jail operators receive $22 to $44 a day per person, creating an incentive to keep victims imprisoned for long period.

A petitioner who was held for four days in a shed attached to a run-down hotel before he escaped told the Los Angeles Times, “I was held in a small room with the door locked from the outside. There was a big iron gate that cut us off from the outside world. There were guards keeping an eye on us all the time. They didn’t beat us. But I was just given green peppers with rice every day for food.” When confronted by the press the owner of the hotel said he had no knowledge of black jails. “They are help centers to assists petitioners with no transportation to get back to their homes. They’re not jails,” he said.

See Separate Article on Petitioners and Black Jails

Torture in China

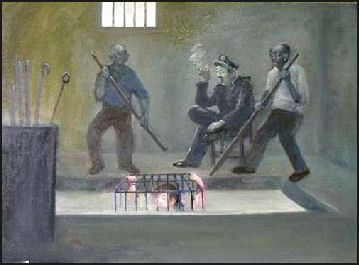

Falun Gong depiction of Chinese torture

According to a 2005 report by Manfred Nowak, the first United Nations human rights investigator to visit China, torture by authorities on detainees is widespread and “a culture of fear” is pervasive. According to the report such abuses can only be eliminated by overhauling criminal laws, giving more power to judges and abolishing labor camps. Nowak complained that there were numerous attempts to “obstruct or restrict” his investigation.

Torture methods used by Chinese authorities, according to the United Nations, have included denying food; using electric shocks, sleep deprivation, burning cigarettes, hoods, and blindfolds; submersing detainees in water or sewage; denying medical treatment, forcing detainees to maintain awkward position for long periods of time; exposing them to extreme heat and cold, and forcing prisoners to squat in a small metal box for days. People sentenced to death or waiting for an appeal are regularly handcuffed and shackled for 24 hours a day and can not eat or use a toilet without the help of other prisoners. Most tortures are designed not to leave any visible marks or scars.

Suspects are routinely tortured to extract forced confessions. According to the United Nations report, “Very often an individual police officer is not instructed to use torture but is under pressure to extract a confession” even though under Chinese law, confessions obtained through torture are inadmissable in court. According to the United Nations study 126 people were killed, including some during police interrogations, in 1993 from torture and 115 on 1994.

In 1998, the government authorized the release of a book called “The Law Against Extorting a Confession by Torture”, which outlined 64 case studies of people being tortured. Victims described in the book were tortured to death using electric cattle prods, drowned in buckets, burned in stoves, hanged and beaten to death.

One tortured prisoner wrote in letter smuggled-out of his labor camp, "On Nov. 8 they begun taking me to the workshop and hanging me from a pillar with my hands cuffed above my head and my feet barely touching the floor, every day for more than 10 hours." "On March 12, they caught me writing a petition about prison conditions. They started beating and kicking me again, and hitting my head with an electric baton." A dissident told the United Nations investigation that he was forced to remain immobile in bed for 85 days with his hands held on the side of his head. If his hands moved while he was sleeping he was woken up and told to resume his assigned position.

Sleep deprivation is a common tactic used by government officials conducting interrogations. One government official told the Daily Yomiuri, “They deprive people of sleep by taking turns to question them. Most people usually give in after three or four days. Police officers can be swayed with connections, but you have to concede defeat if you are arrested by them [government officials].

In December 2003, a man was sentenced to death by China’s highest court even though eight prison guards admitted torturing him to extract a confession. A Chinese legal expert said the decision was made because the government didn’t want a precedent set that confessions could be disallowed if they were extracted by torture.

See Separate Article on Dissidents and Falun Gong on torture some of them underwent

Murderers as Interent Martyrs in China

Stephen Caraher of China Geeks wrote, “Qian Mingqi and Yang Jia are two Chinese men that committed multiple counts of homicide. What Qian Mingqi did could even be considered an attempt at mass murder. Yet both men — murderers — have been embraced, by and large, by the Chinese internet as martyrs. Qian is even being compared to the revolutionary hero Dong Cunrui. Xia Junfeng’s case is a bit different in that his crime was allegedly committed in self-defense, but he too has become a kind of hero. [Source: Stephen Caraher, China Geeks, May 29, 2011]

Most Chinese would, as I would, back away from actually endorsing the final, violent actions of Qian Mingqi or Yang Jia. But the fact that both figures have received such widespread sympathy is evidence that many, perhaps most Chinese people can relate to them and their stories. They may not agree with what Qian did, but they can understand how he got to that point. This is a decidedly bad sign.

After all, what Qian and Yang have in common is a history of mistreatment by the authorities, and when they attempted to redress their grievances through legal channels, they met with resistance, harassment, and ultimately failure. Their turn to violence arose from depression and desperation. Think about what it means that millions of people can relate to that well enough to take the side of mass murderers.

The Qian Mingqi-Dong Cunrui comparison is especially interesting because Dong’s death was (as he shouted before he blew up) “for a New China.” As the story goes, Dong’s sacrifice helped install the current regime. If people see Qian as a new version of Dong, what dream of China was he dying to protect (or project)? Whatever the answer, I feel quite certain it is not the China of Hu Jintao.

Lack of Freedom in China

In China there is no political opposition and there aren’t freedoms of speech, freedom of press. In China there is a saying: “Do what you please as long as you please the Communist Party.”

In the official Communist English-Chinese dictionary "freedom, liberty" is explained with series of definitions: 1) "Citizen of China enjoy freedom of speech, correspondence, the press, assembly, association, procession, demonstration, and freedom of strike; 2) "Bourgeois ideas must not be allowed to spread unchecked”; 3) "The petty [sic] bourgeoisie's individualistic aversion to discipline;" 4) "Liberalism is extremely harmful in a revolutionary collective;" 5) "We can't decode this matter for ourselves; we must ask the leadership for instructions." [Source: "Riding the Iron Rooster" by Paul Theroux]

See 1) Informers and Neighborhood Watch Committees, See Society; 2) Religion and the Chinese Government Freedom, See Religion in China, Religion; 3) Freedom of the Press. See Media, Communications, Internet.

In September 2005, police raided the offices of an American-funded human rights group — the Empowerment and Rights Institute — which had carefully documented complains about problems such as land confiscation and police torture.

Beijing promised to open and improve human rights as it prepared to host the Olympics in 2008. See Media, Internet, Justice System

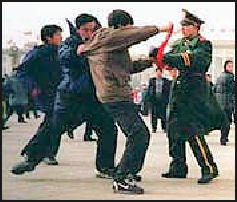

Repression in China

Arrest of Falun Gong members

Perry Link of Princeton University said that Beijing discourages potential opposition by using “an essentially psychological control system that relies primarily on self-censorship.” A common tactic is to accuse a person regarded as a threat, no matter what their true beliefs are, of anti-Chinese, anti-socialist activities in the media and intimidate anybody willing to take his side.

Security forces tap phones, listen in on mobile phone conversations and monitor what people check out on the Internet (See Internet). Being called in “for tea” by the “relevant departments” is Chinese code for being questioned by security police. The use of the word "the enemy" comes from Mao's famous 195 7speech, "On the Correct Handling of Contradictions Among the People", which instructed officials, when dealing with alleged offenders, to distinguish between two types of social contradictions: those "between the enemy and us" and those "among the people". The former were to be handled with the unremitting severity of dictatorship.

Explaining the Chinese concept of "state security" Robin Munro of Human Rights watch/Asia told the New York Times, "We know what China means by state security. It means suppressing perfectly innocent and innocuous dissidents by putting them in prison for 15 years."

Parents involved in illegal political or religious activities are sometimes punished by denying their children birth certificates and documentation so they can enter school. Chinese officials have occasion approved the kidnapping of suspects abroad and brought back to China to be tried in Chinese courts.

The government is afraid of unauthorized activity involving large numbers of people and organized opposition. One very vocal critic of the government that managed to avoid arrest told the New York Times that the secret is knowing where to draw the line. “If you talk every day online and criticize the government they don’t care. because it is just talk. But if you try to organize — even if its just three or four people — that’s what they crackdown on. It’s not speech; its organizing.”

1) Repression Against Catholics and Christians, see Christian, Islam and Jews, Religion; 2) Repression Against Tibetans, See History Under China; Religious Repression, Religion Tibet; 3) Repression in Western China, See Separatism, Terrorism and Human Rights, Xinjiang, Northern and Western China, Minorities.

Banner unfurled at the Great Wall

More Freedom in China

China is freer than it used to be for most Chinese but less free for groups singled out by the government as threats. People can say what they want as long as they do not organize demonstrations or insult top leaders in print. Neighborhood committees have collapsed. Work units only have control over people who work in state-owned industries but less and less people work at these industries and their power over workers has been diminished.

The Chinese people are arguably freer now then they have ever been in their history of a people. Freedoms enjoyed today by hundreds of millions of Chinese that were prohibited in the Mao era include taking vacations, wearing what you want, traveling outside of China, changing jobs, getting divorced, speaking on talk radio, living were the want and voting for local leaders. One teenager at a bowling alley in Shanghai told Newsweek, "We can make money and have fun. We can do whatever we want."

Lawyers and others in China have been increasingly assertive in recent years regarding rights already promised under the Constitution. Journalist are exposing more cases of corruption; historians are investigated “black spots” in history; lawyers are taking on cases involving the rights or workers and migrants; and publishers are publishing book on formally taboo subjects. Foreign pressure has less effect than it used in part because Beijing is very much in control of its own destiny and needs less from West than it used to is less susceptible to Western leverage.

A Chinese professor told Newsweek, "In the old days, if you were overheard saying Chairman Mao looks like an old lady, they would throw you in jail for 17 years. But today, if you are overheard saying [a Chinese leader] looks like an old turtle, nothing will happen to you, unless you say it to the press at Tiananmen Square.” It also not a good idea to express sensitive viewpoints in print. Wang Ruoshui, a democracy advocate and former editor for the People's Daily told the New York Times: “If you want, you can dress like a pirate on the street and you can say anything you like; you can attack...the Communist Party as long as you don't publish you views."

Some Chinese out there appear to crave American-style freedoms. On teacher wrote on his blog: “I have been extremely [hurt] for not being born in a free country such as the United States which respects human rights. [This has led] to my suffering [for] more than 10 years after my graduation [from university] and from the 17 years [of] awful education. I asked god repeatedly: why do you put me in dictatorial and dark China while giving me a soul devoted to freedom and truth?”

One very vocal critic of the government that has managed to avoid arrest told the New York Times that the secret to staying out of jail is knowing where to draw the line. “If you talk every day online and criticize the government they don’t care because it is just talk. But if you try to organize — even if its just three or four people — that’s what the crackdown on. It’s not speech; its organizing.”

Repression's Paradox in China

Lester R. Kurtz wrote in Open Democracy: “From the authoritarian’s perspective, internal dissidents are easy to deal with — put them in jail, have them disappeared, exiled, or executed. The repression of dissidence, however, is always risky and more often than not backfires, fueling more opposition and frequently leading to delegitimation of a regime and even defections from its institutions of power — that is the fundamental paradox of repression. The People’s Republic of China has had pretty good luck with repression, however, more so than most regimes, having successfully crushed a nascent opposition movement in the iconic Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989 even as similar resistance actions fueled uprisings or broad-based movements elsewhere in the world. [Source: Lester R. Kurtz, professor of public sociology at George Mason University, Open Democracy, November 17, 2010]

The negative fallout from that apparent success continues to soil China’s image, however, and influence geopolitics just as it did in 1989. Following the Tiananmen attack on unarmed student protesters, a tsunami of resistance suddenly arose within the Soviet bloc, inspiring protesters and intimidating an embarrassed Mikhail Gorbachev. The Soviet president had been left almost single-handedly flying the communist banner while trying to reinforce legitimacy by championing democratic and economic reforms far beyond anything the Tiananmen students had demanded of their government.

Walls came tumbling down in 1989 — not the Great Wall of China, of course, but the Berlin Wall and other less physical structures of authoritarian control. When East German Chancellor Erich Honecker called for a Tiananmen solution to German dissidence in the fall of 1989, his own security chief rebuffed him. Gorbachev’s foreign minister literally announced that “the Sinatra Doctrine” (“I did it my way”) would be Moscow’s response to the wave of unrest across Eastern Europe in the wake of Tiananmen Square. There would be no Soviet troops backing a crackdown on Soviet bloc insurgents.

From 1989 until today, the line of descent in regimes’response to dissent makes many in the proverbial international community distrust the Chinese government and look for heroes of discontent” such as Liu Xiabao, who has become “perhaps the leading representative of human rights but he also became a universal symbol of human rights."

It will not be easy, of course, for other nations to ignore Chinese threats, and we already see French, British, and other diplomats awkwardly attempting to negotiate away this problem, inconvenient as it is to their desire to placate the new economic superpower. They cannot afford to lose lucrative trading deals with China, where the government still holds the contract-signing pens, though they cannot also embarrass themselves in front of global and domestic human rights advocates.

The problem with repression is that unavoidably it has an audience — that is the point, after all (chicken-slaughtering to scare the monkeys). But, it is one thing to beat your child in the privacy of your home to enforce parental control, where you may well be able to escape the consequences of this abuse, but quite another to do it in the streets in front of a crowd of witnesses (although studies suggest the home remedy is counterproductive as well). When those watching are allies, trading partners, and potential adversaries, the paradox of repression kicks in: it is likely to inspire increased resistance, recruit sympathizers, and weaken the authority of the oppressors.

Many observers and practitioners of nonviolent civil resistance, which is now utilized in movements and campaigns for rights in many countries, believe that China is experiencing a gradually intensifying internal civic struggle in which advocates of greater political as well as social and economic rights are becoming more resilient in the face of authoritarian control. China’s engagement with the world, and its need to foster individual entrepreneurship and local innovation as well as to resolve internal social problems in order to vault itself into global supremacy, is at odds with the suppression of free speech and civic self-organization, which hold public institutions accountable and help correct or mitigate inequalities and injustices that weaken state legitimacy.

Without those brakes on an unresponsive state, government becomes an impediment to achieving the nation’s dreams. Ultimately China’s people are the real repository of those dreams. What they decide to do, when faced with continued repression of speech and organizing, will no doubt determine what kind of political changes lie in store for China.

Image Sources: Human Rights Watch, Falun Gong, Students for a Free Tibet. YouTube

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2012