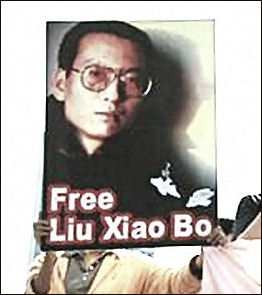

LIU XIAOBO, WINNER OF THE NOBEL PEACE PRIZE IN 2010

Liu Xiaobo — an impassioned literary critic, political essayist and democracy advocate repeatedly jailed by the Chinese government for his writings — is one of China’s most important intellectuals and political activists. Perhaps China’s best known dissident, he helped to draft Charter 08, a manifesto signed by more than 8,000 people calling for modernization and reform, and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010. Liu died in July 2017 of cancer, after being denied of the best medical care available, while y serving an 11-year term on subversion charges in a Chinese jail.

In December 2008, Liu Xiaobo was given an 11-year prison sentence on subversion charges in what was seen as a warning to anyone who dares to challenge the ruling regime. Liu posted essays critical of the Chinese government on the Internet and helped draft the Charter 08 petition calling for a new constitution that guarantees human rights, open elections of public officials, and an end to one-party rule. More than 10,000 people, including some f China’s top intellectuals, signed it but news blackouts and Internet censorship have kept most Chinese from becoming aware of it. One of things that Charter 08 called for was getting rid of the subversion laws that were used to arrest Liu.

“Blacklisted from academia and barred from publishing in China,” the New York Times reported, “Liu has been harassed and detained repeatedly since 1989, when he stepped into the drama playing out on Tiananmen Square by staging a hunger strike and then negotiating the peaceful retreat of student demonstrators as thousands of soldiers stood by with rifles at the ready.” For all these years, Liu Xiaobo has persevered in telling the truth about China and because of this, for the fourth time, he has lost his personal freedom,” his wife, Liu Xia, said.

Liu is a poet and literary critic. His books include “The Fog of Metaphysics”, a review of western philosophies. One of Liu's most scathing essays is "The Philosophy of the Pig," a meditation on how members of the Chinese intelligentsia have sold out, even as far less eminent figures are brave enough to confront the system.

Hannah Beech wrote in Time: “With his unpolished manner and unfashionable wardrobe, Liu has sometimes seemed like the kind of bumpkin who would be entranced by the modern Chinese dream. He has none of the studied élan encountered in overseas intellectual salons. Enter a boisterous restaurant to meet him and it's easy enough to think the skinny guy loitering in the back is an off-duty waiter, not a distinguished scholar.”

Describing Liu in 2007 Evan Osnos wrote in the The New Yorker: “Liu had always been a classic type of the Chinese intellectual class — lean as a greyhound, bespectacled, with a wry sense of humor — but on this December day he looked even gaunter than usual: his belt looked it like was wrapped nearly twice around his waist, and his winter coat drooped. Unlike some Chinese scholars popular in the West, he exuded no aroma of privilege: he had no dual appointments at universities abroad, no obvious awareness that he could be the toast of New York or Berlin, no Davos-worthy polish. Nor did he have the posture of a firebrand. Instead, he struck a technical and unhurried tone as he explained why he had co-authored an open letter that summer, urging Chinese leaders to do more on human rights. He described it not as an act of provocation, but one of duty. [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, October 8, 2010]

Perry Link said, "One reason Liu Xiaobo is admired in his circles is that he won't leave. He wants to stay. He has made a different decision." China has attempted to delete all mention of Liu Xiaobo's works from the public eye while concurrently printing state-backed slurs on his reputation in state media. Government censorship has left Liu's supporters and contemporary human-rights campaigners who speak out against abuses by the party marginalized - and with little choice but to flee, quieten up, or face lengthy jail terms.

Liu Xiaobo’s Early Life and Intellectual Activity

Describing Liu’s early life in the Jianying Zha wrote in The New Yorker,”Liu, who was born in 1955 to provincial intellectual parents, spent his teen-age years in Inner Mongolia, where his father had been sent as part of Mao’s Down to the Countryside movement, and he worked as an unskilled laborer during his early adulthood. After Mao’s death, he went to college at Jilin and did his doctoral work in literature at Beijing Normal University, where he began teaching in 1984. In the mid-eighties, he caused a sensation with scathing critiques of prominent scholars and intellectuals of the previous generation, whose work he dismissed as derivative and mediocre. Some of his more mischievous assertions were made during a 1988 interview with a Hong Kong magazine: “After a hundred years of colonialism, Hong Kong became what we see today. China is so big, of course, that it would take three hundred years of colo- nialism to make it like Hong Kong today.” [Source: Jianying Zha, The New Yorker, November 8, 2010]

Delightedly piling outrage upon outrage, he pronounced Confucius “a mediocre talent,” and called for China to be thoroughly Westernized. He dismissed the writer Gao Xingjian, who went on to win the 2000 Nobel Prize in Literature, as a rank imitator. He claimed that there was “nothing good” to say about mainland Chinese authors, not “because they were not allowed to write but because they cannot write.” For an iconoclast like Liu, cultural critique and political reform were part of the same struggle.

I first met Liu in early 1991, at a small hot-pot dinner celebrating his release from prison, and recall the glee with which he mocked various cultural luminaries. He provoked an argument after he told a fashionable young novelist at the table that the eminent critic who’d discovered and championed him was nothing but an ignorant trend monger. He could be overbearing, and at times unbearable. But his critical lance was accompanied by genuine courage and political conviction.

Liu Xiabao’s Character

Bei Ling, a poet and essayist an old friend of Liu wrote in the Taipei Times, “Liu Xiaobo is very gentle, but he cannot stand any false kindness; he emphasizes individualism, though in daily life he needs his friends very much ... His unique personality highlights exactly the kind of character that is so extremely rare among Chinese intellectuals.” [Source: Bei Ling,, Taipei Times, November 2, 2010]

“I am trying to describe him with simple words, because he is such a man of flesh and blood, a very resolute man; a man of action who is also deeply immersed in thinking. Some people go to jail, and what they leave behind are their deeds and opinions, while their personality and their image become more and more blurred. But he, a man of such strong opinions, has left us so much character and spirit, so many stories — and for me there is also a kind of silent frustration, when I think back to more relaxed times, which makes me not at all relaxed now.” [Ibid]

“This is my friend, my good friend Liu. He is a very fidgety professor, pacing back and forth through a room, cigarette in his mouth, absent-mindedly trying to brush off some dirt from his shirt with one hand, with the most inane expression on his face, asking me the most trivial questions about my daily life. He gets on my nerves, my face may even begin to show it. I am trying to answer him, to somehow enter his system, so I can develop my anxiety within his stammering questions. Or maybe I can change the subject, ask him a few metaphysical questions and make him go on talking till morning.” [Ibid]

“As long as you are with him, you have no rest anyway; you have to travel along the way of his thoughts. He will expound on Kant, and in the next moment he has jumped to Camus. I have often heard him repeat that sentence from The Myth of Sisyphus, where Camus says: “I have never heard of anyone who died for ontology.” He even told me that at his home in Beijing he would recite his favorite classical books from the West to his wife, his son and the walls. He said he had recited A Hundred Years of Solitude three times all the way through, and he can make you believe that he has recited Schopenhauer’s Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung (The World as Will and Representation), also three times.” [Ibid]

“In a nutshell, according to common custom, he had too many faults, but his unique personality highlights exactly the kind of character that is so extremely rare among Chinese intellectuals. He is very gentle, but he cannot stand any false kindness; he emphasizes individualism, though in daily life he needs his friends very much.” [Ibid]

“Actually, he is easy to get along with; he knows how complicated people can be and still keeps yearning for simplicity. He speaks the truth and never tries to gloss over human weakness. His understanding comes close to “the-thing-in-itself,” but he never styles himself as speaker of “the real thing.” The more you get to know him, the more you can sense something like an instinctive breath of fate. [Source: Bei Ling is poet and essayist who divides his time between Germany and Taiwan. He was imprisoned in 2000 in Beijing for trying to publish Tendency, a literary magazine. He founded the Chinese PEN Center (ICPC) in exile]

Liu Before Tiananmen Square

Bei Ling wrote in the Taipei Times, “In the spring of 1988, in this volatile period, I had a strange idea. I wanted to find someone who could “team up for prattling” with him. So I wrote him a note on a piece of paper and gave it to a friend who would visit him that day. I just asked him to come to a certain classroom at the Foreign Languages Institute at Weigongcun, at 2 o’clock on a certain day. “See you there!” That was all. By that time he was already teaching at Beijing Normal University. But he came, riding his bike, at the time I had requested. [Source: Bei Ling,, Taipei Times, November 2, 2010]

“When he saw me, he asked half in jest what kind of holy mission I had in store. I just led him into the room and introduced him to the poet Duo Duo ( and other writer friends waiting there for him. Liu was very surprised, but he understood what I had in mind. We sat down, and Duo Duo began asking questions, with a little assistance from me.” [Ibid]

“From the May Fourth Movement of 1919 we moved on to the European enlightenment; from Kant we leaped to Wang Guowei, the Chinese historian and literary critic at the beginning of the 20th century; from Liu’s take on a series of Western philosophers he moved on to his opinion on a whole bunch of famous Chinese intellectuals. Liu just kept going, one question after the other. This was the time when many books from the West were translated at once.” [Ibid]

We started from socially engaged thinkers like Camus, Sartre and Hannah Arendt, then Liu dissected a few problems in the works of the famous contemporary Chinese philosopher Li Zehou and spoke of the Chinese intellectuals’ split personalities in times of dictatorship. After a few hours like that we had come to face reality; we were overcome with sadness.

“At the time, Liu was called a dark horse; first he startled the established literary world with his critical theory, then he used his thorough knowledge of classical Western philosophy to stir up a Chinese world of thinking that was only just taking form again after the Cultural Revolution. People spoke of the “Liu Xiaobo phenomenon” or the “Liu Xiaobo shock.” At all the private book stands in the capital, Liu’s book A Critique of Choice — Dialogue with Li Zehou was only available at several times the original price, and even then you were made to buy two other slower-selling tomes on top.” [Ibid]

“It was April in New York when he called me. He was determined to return to China within the next two days. In fact, he had already bought a non-refundable ticket where the date could not be changed. I put down the receiver and hurried over to his place. Once I saw him, I said: “Xiaobo, I am proud of you. You go first, I’ll follow you soon.” He showed nothing anymore of the confusion of the days before. With a rare calm, he said, still a little haltingly: “Bei Ling, we ... at this time ... we cannot go on waiting here in New York, isn’t this the moment we kept preparing ourselves for all our lives?” [Ibid]

“In those days we sat in front of the TV night and day, watching thousands and thousands of enthusiastic young students walk in the streets, demonstrating for the future of our republic. They were so sincere. What were we doing, getting excited and crying in New York in front of the TV — we had to go back, to be part of Beijing, together with the students.” [Ibid]

“Finally, he just went, without looking back. He was prepared to go to jail, even prepared to be arrested on arrival at the airport, and he knew how they treated intellectuals in prison. But what we had not expected was that our government would let the army open fire on the students, would let tanks and armored vehicles drive over the bodies of ordinary citizens. Who would have wanted to imagine such cruelty?”

Liu Xiaobo at Tiananmen Square

In 1989 Liu was a visiting scholar at Columbia University in New York. He was in New York Times when the Tiananmen Square demonstrations began. Zha wrote: “For many liberals, it was a stand-up- and-be-counted moment...when he learned of the protests, he promptly gave up the fellowship and flew back.

Liu joined the hunger strikers at Tiananmen square. Despite a reputation as an angry young man in Chinese scholarly circles, he quickly became a leading proponent of nonviolence. As the People's Liberation Army (PLA) began to move on the demonstrators on June 3, Liu tried to prevent bloodshed by negotiating with troops and urging protesters to evacuate Tiananmen Square. “If not for the work of Liu and the others to broker a peaceful withdrawal from the square, Tiananmen Square would have been a field of blood on June 4,” Gao Yu, a veteran journalist who was arrested in the hours before the tanks began moving through the city, told the New York Times.

Jianying Zha wrote in The New Yorker, “His role in Tiananmen wasn’t simply that of a cheerleader or provocateur: he tried to negotiate with the Army for the students’ peaceful withdrawal from the square. And he may be the only Tiananmen leader who published a book exposing the movement’s moral failings, not least his own.... Liu detailed the vanity, self-aggrandize- ment, and factionalism that beset the student activists and their intellectual compadres. He put himself under a harsh light, analyzing his own complex motives: moral passion, opportunism, a yearning for glory and influence.”

Liu Arrested After Tiananmen Square

After the crackdown, he was attacked by both sides: the government sentenced Liu to 20 months in prison, while some democracy activists pilloried him for having deigned to talk to the PLA — even though his bargaining probably saved many lives.

Bei Ling wrote in the Taipei Times, “After June 4, Liu walked out of the apartment of the Australian diplomat and writer Nicholas Jose at the embassy compound in Jianguomenwai. He didn’t want to hide any more. He had survived, but in this time of dying and killing he needed to be together with his students, with the people of Beijing. He certainly had nothing to be ashamed of. When he left New York, I was worried for him. Going back at this time could arouse the suspicions of the government, he could be seen as a “manipulator” on a political agenda. [Source: Bei Ling,, Taipei Times, November 2, 2010]

However, Liu said: “I am going back to take up my responsibility as a university teacher. Everything I have done in the US is public knowledge. In my writings, I have emphasized the need for intellectuals with an independent character, who are not involved in any political organization. I have supported the democratic process and non-violent principles. Besides, my kind of temperament would not be welcome in any political group.” [Ibid]

Bei wrote: “He walked out into the street and was arrested. He had put his actions behind his words. He had written five books and given numerous lectures. He stammered and then kept on talking up a storm; he took sides all right; his combative style would let the objects of his critique feel that he lacked calm and objectivity. His disregard for “face,” his cutting and uncompromising remarks, made people uncomfortable. He didn’t care at all what people said about him.” [Ibid]

Liu Xiaobo’s Later Political Activity

Liu spent 21 months in prison without a trial after the 1989 Tiananmen protests, and three years in a labor camp starting in 1996 for challenging single-party rule, advocating negotiations with the Dalai Lama over Tibet and publicly demanding the release of those still imprisoned for their roles in the Tiananmen Square protests.

Unlike many other dissidents of that era, he chose to stay in China. Liu was sent to a labor camp in 1996, where he spent another three years for his continued criticism of the nation's closed political system.

Liu was fired from his teaching job. He served as president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center, a charity that defends the right to free speech, and wrote provocative essays with titles like “The Chinese Communist Party’s Dictatorial Patriotism” and met with like-minded intellectuals who urge China to embrace democracy without violent upheaval. He called the Communist Party an “empty-eyed, all-ignorant dictatorship.”

According to a profile entitled “Liu Xiaobo: Biographical Sketch” published in China Daily: “Those who are familiar with Liu know he is extreme and arrogant. He took part in founding an illegal organization called Independent Chinese Writer Club to form his own clique and press down on dissenters, thus making many enemies within the “Chinese democracy activists” circle and was sued in the United States for embezzlement. As a result, many Chinese “democracy activists” overseas are not happy with him.

Charter 08 Parade in Hong Kong in 2011

Liu Xiaobo’s at the Time of Charter 08

Describing Liu at the time Charter 08 came out Jianying Zha wrote in The New Yorker, “At a welcome-back dinner that Liu Xiaobo hosted for my brother, Jianguo, who had just served a nine-year term in prison for pro-democracy activism... Liu tamped down Jianguo’s enthusiasm, and later asked me to caution my brother about his exaggerated expectations. He used a classical formula: “Buyao yilan zhongshan xiao! — “Don’t stand on top of a mountain and think that everything is be neath you!” [Source: Jianying Zha, The New Yorker, November 8, 2010]

“Liu, once a firebrand who equated moderation with capitulation and politeness with servility, had matured. Even as he solicited signatures for Charter 08, he was gracious toward those who declined to sign. A Shanghai scholar told me that after he decided not to sign — he didn’t want to jeopardize a scholarship fund that he was setting up — Liu told him that he fully understood and respected his decision.” [Ibid]

Liu, from his radical anti-Communist youth, matured into a champion of non- revolutionary political reform: he continued to be critical of the government but gave it credit for economic reforms and for those instances where it displayed tolerance. “I have no enemy and no hatred,” Liu said at his trial. In an article published in February 2010, he wrote that political reform “should be gradual, peaceful, orderly and controllable,” that “the order of a bad government is better than the chaos of anarchy.” [Ibid]

Liu Xiaobo and Charter 08

Liu was one of the primary authors of Charter 08, a petition demanding that China’s rulers embrace human rights,judicial independence and the kind of political reform that would ultimately end the Communist Party’s monopoly on power. In December 2008, the Charter 08 manifesto was released by Liu and 302 others.

Many of the principals highlighted in Chapter 08 like “freedom of speech, of the press, of assembly, of association, of procession and of demonstration” — in the word of the Nobel Peace Prize committee — are enshrined in China’s constitution.

“I think my open letter is quite mild,” Liu told The New Yorker. “Western countries are asking the Chinese government to fulfill its promises to improve the human-rights situation, but if there’s no voice from inside the country, then the government will say, “It’s only a request from abroad; the domestic population doesn’t demand it.” I want to show that it’s not only the hope of the international community, but also the hope of the Chinese people to improve their human-rights situation.”

Charter 08 has been called the most important political statement since the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests. See Charter 08

Liu and Zhang Zuhua, a political theorist. began drafting Charter 08 in 2006 with about eight other friends. Their inspirations, Zhang told the New York Times were the Magna Carta, the Declaration of Independence, France’s 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and Taiwan’s 1980s democracy movement. [Ibid]

Zuhua is also pressured by the government. He also has a police guard, and a sedan that follows him. He has been warned that he is under investigation and should not make political waves.

Liu Xiaobo’s Arrest

In December 2008, a day before Charter 08 began circulating on the Internet, Liu Xiaobo was taken from his home to a secret location and was not heard from for several months. In June, he was charged with inciting to subvert state power, a charge often used to jail dissidents. A former university literature professor, he spent 20 months in jail for joining the Tiananmen Square demonstrations in 1989 and another three years in “reeducation through labor” for questioning the Communist leadership and calling for a dialogue with Tibet.

After his arrest was locked up in a windowless room about an hour’s drive north of central Beijing. He is denied access to lawyers, to pen and paper and, except for occasional brief visits, to his wife. He is allowed to ask for books. Among those that e has read are the works of Kafka. His wife Liu Xia said he passed his time in detention watching sports — his captors installed a television — and lying in bed, planning his legal defense. [Source: Michael Wines, New York Times, April 30, 2009]

As time went Liu Xiaobo status was elevated to a level above ordinary dissident. He became an international cause with the crackdown on him and his wife became public-relations dilemma for Chinese leaders.

Liu Xiaobo Sentenced to 11 years in Prison

On Christmas day, December 2009, Liu Xiaobo sentenced to 11 years in jail. The date may have been chosen to minimize international attention. Liu told friends that he knew the risk of imprisonment when he drafted Charter 08. The maximum sentence he could have been given was 15 years.

Liu was regarded as China’s leading dissident at the time. His trial lasted three hours, with only 14 minutes allocated to Lui and his lawyers, The 11-year sentence was seen as particularly harsh. Human Rights Watch said it was the longest sentence given for such a crime since the subversion laws were established in 1997. In February 2010, an appeal from Liu Xiaobo against his 11-year sentence was dismissed.

Liu’s wife, Liu Xia and foreign diplomatic observers were not allowed to observe the trial. Authorities used articles he had written as evidence that he sought to subvert the state, according to his younger brother. Amnesty International expressed outrage at the sentence, which it said was the harshest in 35 subversion cases since 2003. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, December 23, 2009]

Liu’s lawyers have expressed frustration with the judicial process, saying for months that they had no access to their client and that they received the indictment less than two weeks ago, leaving little time to prepare a defense. [Ibid]

After Lui’s sentence was given a speech by Vice Minister of Public Security Yang Huanning was published that said threats against the party would not be tolerated and vowed “pre-emptive strikes” against these threats. At the time, Zhang Zuihua, the primary drafter of Chapter 08, was closely watched by police, Signers lost valued research or teaching posts.

Lui’s sentence was largely seen as a signal that Beijing was not keen on ideas of political reforms, human rights and freedom and openness. Liu's supporters initiated a yellow ribbon campaign for his release. “China's Mandela was born this Christmas,” wrote the influential blogger Beichen. The contemporary artist Ai Weiwei was among those who were present at the sentencing. On Twitter he wrote: “This does not mean a meteor has fallen. This is the discovery of a star. Although this is a sentence on Liu Xiaobo alone, it is also a slap on the face for everyone in China.” Salman Rushdie, Umberto Eco and Margaret Atwood are among 300 international writers who have called for the release of Liu. The United States and European Union have also urged Beijing to free Liu. China’s foreign ministry spokeswoman Jiang Yu told reporters that statements from embassies calling for Liu's release were “a grossinterference of China's internal affairs.”

Liu is being kept at Jinhou Prison in Jinzhou, Liaoning Province. He turned 55 there in December 2010. Before he was sentenced to jail he was kept in a Beijing detention center, There have been reports that Liu's prison guards have given him individually prepared meals rather than standard prison meals. “When I was in prison, I was kept in a small pen with a wall. Since leaving prison, I’m simply kept in a bigger pen that has no wall,” he told The New Yorker,

Liu Xia is under house arrest. Her phone and Internet service are blocked.

Liu Xiaobo’s Wife Liu Xia

Liu’s wife Liu Xia lives in the couple’s fifth-floor flat in a west Beijing apartment building. Police have built a guardhouse there for the guards who watch her. Inside, they take notes to record her comings and goings. When she ventures out, a guard picks up the phone. Soon, a sedan with darkened windowscarrying a man with a telephoto-lens camera is trailing her. [Source: Michael Wines, New York Times, April 30, 2009]

Liu Xia told the New York Times she is not active in politics, and does not even use a computer. I take photos, paint paintings, write poems, read books, cook food, she said. And drink. She said she and Zhang meet weekly to play badminton. Their sedans follow them to the game and wait outside the court until they have finished. Then the automobiles follow them home.

Liu Xia has been held incommunicado since October 2010. She has basically been a prisoner, effectively under house arrest, watched by police, without phone or internet access and prohibited from seeing all but a few family members.

Liu Xiaobo Awarded Nobel Peace Prize

Empty Chair at Nobel ceremony In October 2010, Liu Xiaobo was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize on Friday in recognition of his long and nonviolent struggle for fundamental human rights in China. Liu, who was 54 when the honor was announced, is the first Chinese citizen to win the Peace Prize and one of three laureates to have received it while in prison. Given that he has no access to a telephone, it likely that Liu didn’t even he received the award for some time, his wife, Liu Xia, said. Given his detention, it was unclear how he would take possession of the prize, which includes a gold medal, a diploma and the equivalent of $1.46 million. [Source: Andrew Jacobs and Jonathan Ansfield, New York Times, October 8, 2010]

“Thorbjoern Jagland, the chairman of the five-member Nobel committee, said Liu Xiaobo had become the foremost symbol for the human rights struggle in China. While he acknowledged that China had sought to dissuade the committee from making the award to Liu, he underscored that the committee acted independently of the Norwegian government and believed that it was right to criticize big powers. The Norwegian Nobel Committee has long believed that there is a close connection between human rights and peace, he added.”

“In awarding the prize to Liu, the Norwegian Nobel Committee delivered an unmistakable rebuke to Beijing’s authoritarian leaders at a time of growing intolerance for domestic dissent and spreading unease internationally over the muscular diplomacy that has accompanied China’s economic rise, the New York Times reported. “In a move that in retrospect may have been counterproductive, a senior Chinese official recently warned the Norwegian committee’s chairman that giving the prize to Liu would adversely affect relations between the two countries.”

“In their statement in Olso announcing the prize, the committee noted that China, now the world’s second-biggest economy, should be commended for lifting hundreds of millions of people out of poverty and for broadening the scope of political participation. But they chastised the government for ignoring freedoms guaranteed in the Chinese Constitution. In practice, these freedoms have proved to be distinctly curtailed for China’s citizens, the statement said, adding, China’s new status must entail increased responsibility.”

“The prize is an enormous boost for China’s beleaguered reform movement and an affirmation of the two decades Liu has spent advocating peaceful political change in the face of unremitting hostility from the ruling Chinese Communist Party.”

The Nobel committee keeps its deliberations secret, but speculation that Mr. Liu would win was so intense and widespread that one Irish bookmaker refused to take any further bets last week and said it would pay out those who had already wagered on him. Other contenders among a record 237 nominees included human rights advocates and public figures from Afghanistan, Myanmar and Zimbabwe.

Liu Xiaobo and the Nobel Prize

Empty chair protest Liu was the first Chinese to win the Nobel Peace Prize if you don’t count the Dalai Lama. He was nominated for the prize by Vaclav Havel, the dissident playwright and Charter 77 member who became the president of Czechoslovakia.

Liu Xia, Liu’s wife, met with Liu in prison a few days after the Nobel Peace prize was announced apparently so she could inform him that he won the prize, Liu’s mother-in-law told the Hong-Kong-based group Information center for Human Rights. . Liu told his wife Xia: “This prize goes to all those who died on June 4, 1989" — a reference to people who were massacred at Tiananmen square.

Hundreds marched in Hong Kong demanding Liu’s release and criticized the house arrest of Liu’s wife. A letter signed by 15 Nobel laureates — including U.S. President Jimmy Carter, the Dalai lama and South African Archbishop emeritus Desmond Tutu — urged the G-20 to take action to help free Liu. Not on the list were U.S. President Barack Obama and South Africa’s Nelson Mandela. The U.S. House of Representatives approved a resolution with a vote of 402 to 1 calling for Lui to be freed,

After the Nobel Prize was announced the French government immediately urged China to free Liu. In London, Amnesty International said the award can only make a real difference if it prompts more international pressure on China to release Liu, along with the numerous other prisoners of conscience languishing in Chinese jails for exercising their right to freedom of expression.

Chinese Government Reaction to Liu Xiaobo Winning the Nobel Peace Prize

“The Chinese Foreign Ministry reacted angrily to the news, calling it a blasphemy to the Peace Prize and saying it would harm Norwegian-Chinese relations. Liu Xiaobo is a criminal who has been sentenced by Chinese judicial departments for violating Chinese law, it said in a statement.”

News of the award was nowhere to be found on the country’s main Internet portals and a CNN broadcast from Oslo was blacked out throughout the evening.

In September 2010, Geir Lundestad, the director Nobel Peace Prize selection committee said a senior Chinese Official — Deputy Foreign Minister Fu Ying — contacted him and told not to award the peace prize to Liu Xiaobo, saying that if the committee did the decisions could jeopardize relations between Norway and China. [Source: The Observer]

Beijing said Liu was a criminal and giving him the prize was an “obscenity.” The China Daily said the award was “part of a plot to contain China”, The Global Times said, “The awarding of the Nobel Peace Price to “dissident” Liu Xiaobo was nothing more than another expression of this prejudice, and behind it lies an extraordinary terror of China’s rise and the Chinese model.”

Media reports originating in China geared towards the international audience were not only critical of Liu they were are also harshly critical of the Nobel Peace Prize committee, the Nobel Peace Prize itself and anyone who recognized it. At home all information about Liu and the prize were blocked. Internet searches of “Nobel Peace Prize” and “Liu Xiaobo” in China yielded nothing. On he streets of Beijing, Shanghai and other Chinese few people knew who Liu was, had hear of “Chapter 08" or cared much for human rights issues.

When the decision was announced the Global Times said the Nobel Committee had “disgraced itself” and dismissed the prize itself as a “a political tool that serves an anti-Chinese purpose.” An editorial read: “The Nobel Committee once again displayed its arrogance and prejudice against a country that has made he most remarkable economic and social progress in the past three decades.” “Once again” was a reference to the Dalai Lama being awarded the prize in 1989.

January punished Norway even though the Norwegian government has no say in who gets the Nobel Peace Prize, a decision made by the Nobel Peace Committee. Chinese authorities blocked Norwegian officials from visiting Liu’s apartment and canceled several Chinese-Norwegian events. Trips by various Chinese groups to Norway were cancelled. Trips by various Norwegian groups to China were cancelled because their meetings with Chinese officials were cancelled. A Japanese foreign ministry spokesman said, “It is difficult to maintain friendly relations with Norway as in the past.”

Friends of Liu and people that spoken out on his behalf were roughed up, harassed and prevented from leaving their homes. People who signed Charter 08 were confronted by police; a woman demand recognition of the hundred killed at Tiananmen square disappeared academic friends of Liu received threatening phone calls and were kept from attending events. For a length of time outside were unable able to contact Liu’s wife

The Chinese Foreign Ministry described the award as a “political farce” and said it reflected Cold War mentality and infringed upon China's judicial sovereignty. “(It) does not represent the wish of the majority of the people in the world, particularly that of the developing countries,” ministry spokeswoman Jiang Yu said in Beijing.

Nobel Committee’s awarding of the Peace Prize to Liu Xiaobo was clearly taken as an affront to China’s power, elevating the country’s internal dissent to a global level. There is nothing more infuriating to a regime that doesn’t have to answer to its own people than to have friends and outside observers honoring those citizens who speak out. Liu’s crime was to be a key figure in the proclamation of China’s Charter 08 (2008), a call for democratization modeled after Czechoslovakia’s Charter 77, the prelude to the Velvet Revolution that brought down that country’s communist government in 1989.

From the authoritarian’s perspective, internal dissidents are easier to deal with — put them in jail, have them disappeared, exiled, or executed. It is not so easy to silence the prestigious Nobel committee, however, let alone the vague collective referred to as “the international community.” Of course, that is exactly why Professor Liu was awarded the prize; his message was amplified in a way that could not be dismissed back home. In the global village disputes cannot be stopped at national boundaries. Efforts by states to keep dissent cloistered at home almost always fail, and smart resisters court the global press and key transnational allies.

Human Rights Watch’s Minky Worden notes that China’s recent policy for dealing with dissent involves “killing a chicken to scare the monkeys,” in other words, disseminating terror and therefore gaining submission by making an example of someone harshly punished. The sacrificial victim in this case is human rights activist Liu Xiaobo, formerly Beijing Normal University professor of literature, who was jailed in 1989 after supporting the Tiananmen Square students in their protest. In 2008 he joined more than 2,000 Chinese citizens in signing a charter calling for an end to one-party rule and the protection of human rights and democracy in China. He is one of several singled out as an example that dissent is not tolerated, thrown into prison to deter others from similar criminal dissent.

Unusual Opposition to Liu Xiaobo by Chinese Government

Tibetan support for Liu A group of 14 overseas Chinese dissidents, many of them hard-boiled exiles dedicated to overthrowing the Communist Party, called on the Nobel committee to deny the prize to Liu, whom they say would make an unsuitable laureate. In a letter they accused Liu of maligning fellow activists, abandoning persecuted members of the Falun Gong spiritual movement and going soft on China’s leaders. His open praise in the last 20 years for the Chinese Communist Party, which has never stopped trampling on human rights, has been extremely misleading and influential, they wrote. [Source: Andrew Jacobs and Jonathan Ansfield, New York Times, October 6, 2010]

Among the signers were Zhang Guoting, a writer now living in Denmark who spent 22 years in Chinese prison, Bian Hexiang, who describes himself as a New York-based member of the Central Committee of the Chinese Social Democratic Party, and Lu Decheng, who was jailed for throwing paint-filled eggs at the Mao portrait on Tiananmen Square and now lives in Canada. The letter and calls from other detractors have infuriated many rights advocates, inside and outside of China, who say the attack distorts Liu’s record as a longtime proponent of peaceful change. [Ibid]

Whatever the merits of the anti-Liu Xiaobo camp, their very public sentiments provide a window into the state of the overseas Chinese dissidents, a fractured group beset by squabbling and competing claims of anti-authoritarian righteousness.

Ordinary Chinese Response to Liu Xiaobo Being Awarded the Nobel Prize

Hannah Beech wrote in Time: “Soon after imprisoned Chinese scholar Liu Xiaobo won the Nobel Peace Prize on Oct. 8, a joke made the rounds among Chinese Twitter users able to surmount the Great Firewall that normally blocks the site: "I don't know who this Mr. Liu is," went the gag, "but as a Chinese, I'm very happy for a fellow citizen to win the Nobel Prize. He must be one of our great party members, a great official ... and a great leader who does great deeds for his people." [Source: Hannah beech, Time, October 25, 2010]

“It's far from clear how many Chinese even know that Liu has won the Nobel. Beech wrote. “The news wasn't carried on state television. Live feeds of CNN and BBC were cut when Liu's name was announced by the Nobel Committee, and a party in his honor in Beijing was shut down. Although the state-run Xinhua news service posted a story shortly after his win, quoting the Foreign Ministry's denunciation of the prize, few publications ran it. The front page of the next day's edition of the Communist Party?run People's Daily had nothing on the award. Its sister paper, the Global Times, fulminated that "the Nobel Committee once again displayed its arrogance and prejudice against a country that has made the most remarkable economic and social progress in the past three decades."

“Text messages with Liu's name were quickly expunged by censors, and when you input it in major Chinese search engines, the only returns that come up are a few critical domestic stories. Two days after Liu was awarded the Nobel, a student at Tsinghua University in Beijing took an informal poll to find out how widely known the new laureate was. Of 23 students queried, only four acknowledged that they knew who had won the Peace Prize. On Douban, a Chinese website where users discuss films, music and books, one post asking who had heard of "LXB" got some 50 responses. The thread was deleted 16 minutes after it was started. But even in a censored society, word is leaking out. One fruit seller in the southwestern city of Kunming grabbed the hand of a foreigner and asked whether it was true that the Nuobeier, as the prize is known in Mandarin, had been given to a Chinese. "He's in jail," she whispered. "But I think it's very nice that a Chinese received such a big prize."

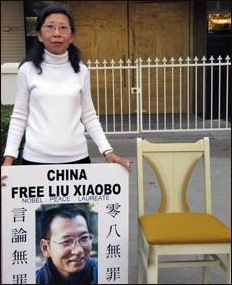

Liu Awarded the Nobel Prize in Absentia

In December 2010, Liu was awarded the Nobel Prize in Oslo. He wasn’t there. China refused to even let his wife attend. Reporting from Oslo, Bjoern H. Amland of Associated Press wrote: “With a large portrait of a smiling Liu Xiaobo hanging front and center, the chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee crossed the dais and gently placed the peace prize diploma and medal on an empty chair. Ambassadors, royalty and other dignitaries rose in a standing ovation....It was the first time in 74 years the prestigious $1.4 million award was not handed over, because Liu is in jail. The last time a Nobel Peace Prize was not handed out was in 1936, when Adolf Hitler prevented German pacifist Carl von Ossietzky from accepting his award. [Source: Bjoern H. Amland, Associated Press, December 2011]

“In China, both CNN and BBC TV channels went black at 8 p.m. local time for nearly an hour, exactly when the Oslo ceremony took place. Security outside Liu's Beijing apartment was heavy and several dozen journalists were herded by police to a cordoned-off area.: In Washington, President Barack Obama said, “Liu Xiaobo is far more deserving of this award than I was.” [Ibid]

In his speech, Norwegian Nobel Committee Chairman Thorbjorn Jagland called for Liu's release, receiving an unusual standing ovation at the international gathering. “He has not done anything wrong. He must be released,” Jagland said. He noted that neither Liu nor his closest relatives were able to attend the ceremony. “This fact alone shows that the award was necessary and appropriate,” Jagland said. He placed Liu's Nobel diploma on the empty chair marking Liu's absence. [Ibid]

Norwegian actress Liv Ullman read Liu's final statement, “I Have No Enemies,” which he delivered in a Chinese court in December 2009 before he was jailed. In the speech, Liu portrays the surprisingly positive and gentle nature of his correctional officer while awaiting trial, which gave him hope for the future. That "personal experience" caused him to "firmly believe that China's political progress will not stop," Ullman read. "I, filled with optimism, look forward to the advent of a future free China," she quoted Liu as saying.

The end of the statement was a love letter to his wife: "I am sentenced to a visible prison," he wrote, "while you are waiting in an invisible one. Your love is sunlight that transcends prison walls and bars, stroking every inch of my skin, warming my every cell, letting me maintain my inner calm, magnanimous and bright, so that every minute in prison is full of meaning. But my love for you is full of guilt and regret, sometimes heavy enough to hobble my steps. I am a hard stone in the wilderness, putting up with the pummeling of raging storms, and too cold for anyone to dare touch. But my love is hard, sharp, and can penetrate any obstacles. Even if I am crushed into powder, I will embrace you with the ashes."

Lynn Chang, a Chinese-American violinist, then performed a haunting Chinese melody, "Colorful Clouds Chasing the Moon" and "Jasmine Flowers." Before the ceremony, 2,000 schoolchildren gathered outside city hall in a display of appreciation for Liu. Some handed letters to Jagland, hoping he could convey their greetings to the jailed laureate. Jagland said awarding the prize to Liu was not “a prize against China,” and he urged Beijing that as a world power it “should become used to being debated and criticized.” Outside Parliament, the Norwegian-Chinese Association held a pro-China rally with a handful of people proclaiming the committee had made a mistake in awarding the prize to Liu.”

Japan, many European Union countries, the United States and at least 46 of the 65 countries with embassies in Oslo the attended ceremony for the Nobel Peace Prize presentation to Liu Xiaobo while 17 countries?including Russia, Pakistan, Iran, Venezuela, Cuba, Sudan Egypt, Vietnam and the Philippines?bowed to Beijing pressure and didn’t attend. About 100 Chinese dissidents in exile and some activists from Hong Kong also attended. Only one of about 140 Chinese activist invited by the Liu’s wife Liu Xia, attend. The one?AIDS activist Wan Yanhai?had fled to the United States. The others were with places under surveillance ir not allowed to leave the country.

Liu’s wife and lawyer Mo Shaoping were prevented from leaving China to attend the Nobel Prize ceremony. Mo was stopped by immigration officials at Beijing airport as he attempted to bard a flight to Europe for the event. Chinese dissident Wan Yanhai, was the only one on a list of 140 activists in China invited by Liu's wife to attend the ceremony. “I believe many people will cry, because everything he has done did not do any harm to the country and the people in the world. He just fulfilled his responsibility,” Wan told AP. “But he suffered a lot of pain for his speeches, journals and advocacy of rights.”

The Nobel Peace prize can be collected only by the laureate or close family members. Cold War dissidents Andrei Sakharov of the Soviet Union and Lech Walesa of Poland were able to have their wives collect the prizes for them. Myanmar democracy activist Aung San Suu Kyi's award was accepted by her 18-year-old son in 1991.

The Chinese created rival award: The Confucius Peace Prize, which comes with a $15,000 check. That episode became a travesty when the recipient of the award?former Taiwanese Vice President Lien Chan?not only didn’t show up to receive the award?given the days before the Peace Prize ceremony in Oslo’she said he knew nothing about it. A young girl accepted the award. It was not known what relation, if any, she had to Lien. Others short-listed for the prize included Bill Gates, Jimmy Carter, Nelson Mandela and the Panchen Lama. Robert Lawrence Kuhn, an investment banker and advisor to the Chinese government called the whole Liu-Peace-prize thing one China’s “worst performance in international statecraft in recent memory.”

"Today in Norway's Oslo, there will be a farce staged: 'The Trial of China'," the Global Times, a Communist Party mouthpiece, said in an editorial. "Recently Western public opinion has not stopped cheering for the Nobel Committee, they are attempting to describe China's 'loss of face' and 'embarrassment'," it said. "No matter how strong the West's opinion, its slap will not be that strong, it will not be able to hoodwink the public."

United Nations Says China’s Jailing of Liu Xiaobo Broke International Law

In August 2011, AFP reported, a United Nations panel has called for the release of jailed Chinese dissident and Nobel Peace prize laureate Liu Xiaobo and his wife, saying their detention breaks international law. The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention criticised Liu's pre-trial detention, saying he was held "incommunicado" and denied access to a lawyer before being sentenced to 11 years in jail in 2009 on charges of subversion.

The UN panel, an independent body made up of human rights experts from five countries, urged Beijing to "take the necessary steps to remedy the situation, which include the immediate release and adequate reparation to Mr Liu Xiaobo"."The government has not shown in this case a justification for the interference with Mr Liu Xiaobo's political free speech," it said in a written opinion dated May 5 and released on Monday by legal rights group Freedom Now. The panel also criticised the house arrest of Liu's wife, Liu Xia, saying she "has the right to be brought promptly before a judge, and the right to legal counsel". She was placed under house arrest after Liu was jailed.

Image Sources: Wiki Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021