CHINESE TELEVISION

Television service is provided by China Central Television (CCTV) in Beijing along with extensive local daily programming and Internet access by viewers to scheduling, reviews, and programming. Television broadcasting in China began in 1958. The first color transmissions were in 1973. In 1978, there were 1 million television sets in China. Today, there are more than 3,000 channels

Television service is provided by China Central Television (CCTV) in Beijing along with extensive local daily programming and Internet access by viewers to scheduling, reviews, and programming. Television broadcasting in China began in 1958. The first color transmissions were in 1973. In 1978, there were 1 million television sets in China. Today, there are more than 3,000 channels

China has the largest number of television viewers in the world — an estimated 95 percent of its 1.4 billion people. This works out to more than two billion eyes.

Changsha is regarded as something of media and cultural center for China. Much of the nation’s animation and television programming is produced there. The immensely popular American-Idol-like “Super Girl” television show was created there.

See Separate Articles TELEVISION AND MEDIA IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HISTORY OF TELEVISION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; GOVERNMENT CONTROL OF TELEVISION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com CCTV (CHINA'S STATE-RUN TV STATION) AND ITS HISTORY, NEWS AND PROGRAMMING factsanddetails.com Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) MCLC ; China Media Project cmp.hku.hk ; China Digital Times chinadigitaltimes.net ; Television Stations chinese-school.netfirms.com ; CCTV english.cctv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Chinese Television Industry” by Michael Keane Amazon.com; “Television Regulation and Media Policy in China”by Yik-Chan Chin Amazon.com; “Two Billion Eyes: The Story of China Central Television” by Ying Zhu Amazon.com; “Playing to the World’s Biggest Audience: The Globalization of Chinese Film and TV” by Michæl Curtin Amazon.com; “TV China” by Ying Zhu and Christopher Berry (2008) Amazon.com; “China's Window on the World — TV News, Social Knowledge and International Spectacles, Tsan-kuo Chang with Jian Wang and Yanru Chen Amazon.com; “Television in Post-Reform China by Ying Zhu, Amazon.com; “The Little Emperors’ New Toys: A Critical Inquiry into Children and Television in China” by Bin Zhao Amazon.com; “China Turned On: Television, Reform and Resistance” by James Lull Amazon.com;

Television in Rural Area in China

Television is popular in the countryside where there is little else to do when people have free time. There, watching television is often a communal activity. If one household doesn’t have a television they can watch shows at their neighbors. Gathering around a single TV set in village to watch a soccer match or popular soap opera has traditionally been a common village activity. By the late 1990s, many people had their own sets. For many Chinese their window to the world was a small black and white television that got two state run channels, later augmented by videos and DVDs.

By the 2000s, televisions became common even in places with unreliable electricity or no electricity at all (they are powered by generators, batteries or car batteries). by this time many villagers had access to satellite television or cable. There were also a lot of villagers who had satellite dishes displayed prominently outside their house but didn’t have them hooked up.

In some cases villagers who made enough from selling cash crops such as coffee or cacao or livestock animals bought a satellite dish for themselves after they saved enough cash. Often an enterprising individual in the village bought a satellite dish and ran cables from the satellite box to his neighbors televisions and charged them a fee. VCRs and DVD players were also common by the early 2000s. DVDs and videos that villagers watched were usually pirated.

Many villagers became addicted to television. Some mud-and-thatch huts lacked furniture but had televisions, which were often turned all day (or whenever programs were being broadcast or electricity is available) and often had ten or fifteen people sitting around it. Studies have shown that people in developing countries that watch a lot of television have less children and buy more consumer goods than those who don't.

Now smart phones are as ubiquitous as televisions in rural areas as well as urban ones are perhaps more people watch TV shows on their phones than on TV.

Satellite and Cable Television in China

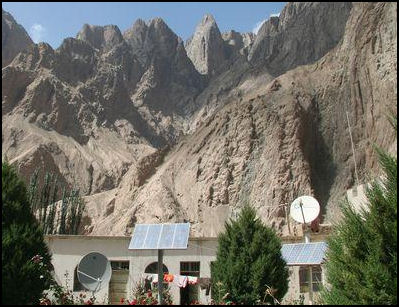

Satellite dishes in Xinjiang

For the most part all television in China is cable. There are no satellite receivers and no aerials. Many Chinese now get dozens or even hundreds of channels on their TVs through cable services. These days many Chinese watch television shows or television-like shows online using streamin services like iqiyi or sohu.com. See Below

Authorities in China initially tried to control the satellite and cable market by requiring all foreign broadcasters to beam through one satellite, the state-owned Sinosat, which receives signals through a ground station and transmits them in-home decoders. This concept didn't work so well. The illegal market for satellite dishes thrived after the effort. Pirates hijacked the signals and sold videos and DVDs of the programs. Falun Gong once hijacked programming on the satellite for an entire week. The decoder boxes themselves were counterfeited.

In August 2005, China announced that it had frozen approvals for foreign satellite broadcasters entering the Chinese market and it would tighten restrictions of foreign television. The move was part of a larger campaign by the government to exert more control on the media and culture industry and “to safeguard national cultural safety.” In 2012, the Chinese government clamped down on light entertainment shows by limiting the number satellite channels allowed to be show.

Satellite dishes brought dozens of channels to even the most remote places. In many cases, the farther one get away from cities the more satellite dishes one sees. In the 2000s, it was common to see advertisements for them in local newspapers. One of the major changes that has accompanied the introduction of electricity to remote areas of China has been the proliferation of satellite television in the same areas.

Video Streaming in China

China is home to the world’s largest online population, with a video-streaming market also among the worlds’ largest. According to data from China Internet Network Information Center, as of March 2020, the number of live-stream users in China was 560 million, an increase of 163 million from the end of 2018, accounting for 62 percent of all online users According to Statista, the value of China’s streaming market reached $177 billion in 2021 and is expected to reach $725 billion in 2025

Leading online video platforms in China in January 2022 (million of monthly unique visitors)

1) iqiyi.com: 168.29168.29

2) qq.com: 157.71157.71

3) youku.com: 139.02139.02

4) sohu.com: 127.96127.96

[Source: Statista]

The online video market in China is highly competitive. The No. 1 position position always come down to a battle between iQiYi, Tencent Video, and Youku. Alibaba’s Youku dominated the online video market for a long time, but its grip has slipped in recent years. Tencent Video was leading the competition in the late 2010s. Tencent Video was the leading online video platform market in the first quarter of 2020, with 900 million average monthly active users and 112 million premium subscriptions. China’s biggest streaming platform in 2022 was iqiyi. Controlled by search engine giant Baidu, it went public on the Nasdaq exchange in March 2018. youku.com, commonly known as the Chinese equivalent of YouTube, is owned by Alibaba' [Source: Tony DeGennaro, Dragon Social, 2020]

See Separate Article Video Streaming Under POPULAR WEBSITES AND INTERNET COMPANIES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Television Production and the Chinese State

Matthias Niedenfuhr wrote in the Political Economy of Communication: “With the move away from a planned economy to a market-oriented economy, the state-dominated Chinese television industry needed to become more profitable. To some degree, China followed the global trend of television production and distribution becoming more and more profit-oriented and less public service-oriented. Production companies and television stations at the central, provincial, and municipal levels used to be fully subsidized but underwent a transition in which subsidies were reduced. Stations were then expected to develop business models with program formats that would generate revenues through t he sale of advertising slots.

This revenue generation can only be achieved by catering to the preferences of the audience since the main currency in this new business model is the value of advertising time-slots, which are directly linked to the ratings of the respective programs. By introducing pay-TV in the form of cable services in place of the formerly free television broadcasts of the early 2000s, it was possible to add yet another revenue stream. On top of the advertising revenues, state-owned television stations could now charge twice for the same product — to the companies that advertise and then the audience. This, however, exacerbates the aforementioned marketization — political control dilemma that the authorities face, since the preferences of the audience had to be taken into greater consideration.

A conflict of interests may arise when the audience prefers content which does not coincide with the preferences of the authorities, i.e., when it favors entertainment over propaganda. While content deemed harmful to society (such as the portrayal of excessive violence, sex and promiscuity, gambling, and other ‘vices’) is targeted by ‘moral guardians’ in many Western countries, in China there is another set of ‘taboo’ subjects — those that threaten the political stability of the one-party-state by questioning the legitimacy of party rule, ev en if obliquely.

“For obvious or sometimes seemingly arbitrary reasons, authorities curb certain formats or ban them altogether. Examples include beauty pageants, talent shows or game shows, or sometimes copies of foreign formats like ‘American Idol’. On the surface, these programs are very much entertainment-oriented and non-political, but the materialistic message in them can be deemed problematic by the media watchdogs. In the latter case, the mere fact that people vote for their favorite candidate in such shows can be categorized as potentially threatening, since people Niedenfuhr 98 thereby become accustomed to voting on a provincial or even national scale — a privilege they are obviously denied in the political sphere (with the limited exception of local elections). [Source: Matthias Niedenfuhr, Political Economy of Communication no. 1, 2013]

Television Advertising in China

TV CTS van Michael Keane wrote: “One of the things I notice about Chinese TV programming is the nature of spot advertising. Whereas in most international television systems commercials are produced by agencies, in the PRC they are often contracted to small companies associated with the producers of programs. [Source: Michael Keane, a Professor of Chinese Media and Communications at Queensland University of Technology, Creative Transformations, June 2013]

“I live in a country where TV commercials exploit humour. Many successful commercials use absurd characters and embarrassing moments. A minority of advertisements are factual endorsements. Humour like creativity, entails bringing together ideas in a surprising way that attracts people’s attention, often releasing endorphins which predispose consumers to remember the name of the product.

“The Chinese word for advertising is guanggao, literally to ‘widely tell’; another synonym is xuanchuan, ‘to declare, pass on’. xuanchuan is also the word for propaganda. In the PRC commercials ‘pass on’ information about new products and their virtues; they ‘tell’ about the effectiveness of products. Commercials show happy families and often recruit celebrities to endorse benefits. In particular, by way of comparison with most international TV markets, irreverent humour is far less evident in TV advertising.

In July 2006 China imposed a ban on television and radio advertising of products that promised breast enhancement, weight loss or increased height. The Beijing news service reported: “Recently some medical organizations have exaggerated the results of treatment provided using experts and previous patients on television commercials to mislead others."

China and the International Television Business

Creative Transformations reported: To understand some of the forces at work in the Chinese television industry “it is worth considering how television content moves across national borders. The television industry has seen three different models of internationalization. The first is licensing of programs, the second model is international co-production, and the third is adaptation of program concepts from one place to another. A fourth model is imminent. [Source: Creative Transformations, May 2014]

“Licensing of programming, the first model, is self-evident. A program is recorded for transmission in the home territory. The program doesn’t change when it is sold, although subtitles can be added for export to new territories. Over the past several decades program distribution has predominantly taken the form of licensing in different territories, a process assisted by regional offices and annual television markets (e.g. MIPCOM). The revenue gained from ancillary markets is significant taking into account that production costs are already covered in the home market. This model of television distribution is dominated by the major studios in Hollywood which send their expensive products into new territories, for example shows like Disney s Lost and ABC’s Desperate Housewives. Yet the downside of this model in territories like China — and other parts of Asia — is the massive loss of revenue through piracy, made even more acute by file sharing technologies.

“The second model, co-production, has attracted a great deal of attention in recent years in China. Co-productions have made headway in China because they offer a way into the market, as long as the necessary conditions are met, for instance, censorship of political ideas and incorporation of Chinese elements. Producers often talk about co-development, referring to the strategy of co-writing stories that will accommodate both parties, although in China this road is littered with failures. Co-productions are more evident in film and documentary than television; they came to prominence internationally in the mid-1990s as a result of economic and technological changes which made ‘runaway productions’ more feasible as well as providing opportunities for less powerful content nations to work together officially.

“Formats are third model. The international trade in television formats took off in the 1990s. The circulation of TV program ideas internationally has facilitated the emergence of new national sources of formats, with format concepts developed in Japan and Korea. Japan’s Iron Chef is a well-known export. In the past two years Korean formats such as Where Are We Going Dad? (baba qu na’er have become very popular in the PRC as have international franchises like The Voice of China, China’s Got Talent and The X Factor China. Chinese television’s acceptance of the rules of the international format trade, however, has taken time to register and as I have discussed elsewhere there have been many recriminations and accusations of foul play.

“The fourth model, which industry analysts now call ‘connected viewing’, is more about distribution than production. Although content is still king, the speakers in the Grand Hyatt Ballroom are the ‘new king kongs.’ These savvy and well-connected entrepreneurs understand there is a massive market for new genres and formats of media among audiences disenchanted with the heavily restricted fare of the traditional broadcasters.

Television Production and Actors in China

On Chinese television one person wrote on the Internet: “Our own actors are not bad. Those responsible for making Chinese TV shows are the directors, screenwriter, editors and people doing the lighting. music, special effects and makeup...are of poor quality in every aspect, and it adds to total trash.”

Television attracts talent because it pays well. But most of the money ends up in the hands of producers and television executives. Performers earn relatively little. Actors on Our Lives, a Chinese version of Friends, got $120 per episode as opposed to $1 million, which is what the American actors on Friends received. If actors become popular they can earn good money through endorsements.

Rachel DeWoskin, a Columbia University who was the lead character in a 1990s show called the Foreign Babes in Beijing when she was 22 years old, at that time was paid $80 an episode, each of which took two to five days to shoot. DeWoskin said she had to show up for work at 6:00 am along with the Chinese actors, who she said were treated badly. "Chinese actors have no leverage," she told the Los Angeles Times. "They live in the studio dorms, eat in the studio cafeteria, wait around on the set for hours...and do not complain. For 750 yuan [$90] 'they own you.'"

See Separate Article CHINESE FILM STUDIOS AND MAKING CHINESE FILMS factsanddetails.com

Ranking of Chinese TV stations on 2005

Chinese Television Stations

Although all television stations are still state-owned, stations owned by provincial governments now compete with one another for ratings, national cable distribution and advertising revenue. The profits from these stations go back to local agencies, so provincial-level officials. [Source: New York Times]

Most Chinese television stations receive only limited financial support from the government and must rely on advertising revenues to survive. Nearly $4 billion was spent on advertising on Chinese television in 1998, an 11 percent increase from 1997. China's huge television market is run by a monopoly that pays very small rights fees.

State-run television in China has become increasingly deregulated in part to attract foreign investors and venture capitalists. In 2004, the State Administration for Radio, Film and Television allowed foreign companies for the first time to take a minor share in Chinese television stations. By 2008 many state-run stations are expected to be effectively independent, relying on advertisers rather than the government for revenues.

Zhu Xudong wrote in Quora, China has one central TV station which is CCTV. Every province and direct-controlled municipality (province) has a TV station, like Zhejiang TV Station. Every city (county) has a TV city, like Hangzhou TV station. Well, Hangzhou is a big city but it's the same with small cities (maybe with a few exceptions in less developed part of China). As far as I know, most towns do not own a TV station. So you would think the number of TV stations should be roughly the same as the number of counties in China which is around 2,800. Wrong! [Source:Zhu Xudong Quora, 2015]

Because there are other types of TV stations, such as Educational TV Station (roughly the same size as above) and other TV stations. These are hard to count because ordinary Chinese people are less familiar with them. However, if you want a number, I found in one article saying there are around 4,000 TV stations in China as of 2007.

TV channel is more difficult to count because different TV station has different numbers of TV channel. CCTV has 45 channels. Zhejiang TV has 14 channels. Hangzhou TV has 7 channels (including one in beta) and some TV stations in small cities only have two or three TV channels. So maybe you could try to do the maths here. It's already getting too difficult for me:)

Popular Television Stations in China

Leading television stations in China in 2020, based on media power score: 1) China Central Television (CCTV): 97.9197.91; 2) Hunan Television: 80.3680.36; 3) Zhejiang Television: 75.1775.17; 4) Shanghai Television: 74.2474.24; 5) Guangdong Television: 73.5973.59; 6) Jiangsu Television: 73.2673.26; 7) Beijing Television: 72.1272.12; 8) Shandong Television: 71.8371.83; 9) Hubei Television: 70.1170.11; 10) Fujian Television: 68.4768.47 [Source: Lai Lin Thomala, Statista, July 16, 2021]

3) Phoenix Satellite Television is a Hong Kong-based Chinese television broadcaster that serves the mainland China, Hong Kong and other areas where Chinese live around the world. Phoenix TV has links to the Chinese military and features many news stories that are not shown in mainland China. It is said its reporters are more gentle than mainland ones. See Phoenix Television Under HISTORY OF TELEVISION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

4) Shanghai Dragon Television (Dragon TV) is a provincial satellite TV station. It launched in October 1998 as "Shanghai Television" (it changed its name in 2003). It is famous for Ultimate Challenge and JinXing Show. The 80’s Talk Show features a funny anchor. Shanghai Oriental Television, a different dtation, began broadcasting in 1993. It features news, sports, education, arts, movies and plays. 5) Jiangsu Satellite Television is a provincial channel based in Nanjing city. It’s most famous program is “If You Are the One“, a weekly variety dating show featuring talented model, unique topic and exquisite packaging. "Strongest Brain" is also popular. 6) Zhejiang Television is a Zhejiang province’s provincial TV channel. The channel became famous for its popular singing contest program “The Voice of China“ (China’s version of "The Voice"). The station has come a long way in recent years. “Running Man” is another popular show.

7). Shenzhen Satellite TV is based in Shenzhen, Guangdong province. The channel broadcasts Chinese music, news and Chinese talk shows. 8) The Travel Channel is China’s national tourism satellite TV channel. It covers travel news, fashion, entertainment and many other fields. The Travel Channel is located in the beautiful Haikou, Hainan Province. 9) Anhui Television is a television network in Hefei, Anhui province. It began broadcasting in 1960. 10) Xing Kong TV is a Mandarin language TV channel with drama series, comedies, variety and talk shows and game shows. Xing Kong is currently available in Mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau and some countries in Southeast Asia. In addition, Dongfang Satellite is also well-known. In every province or city, there are some channels that broadcast shows only people in that province or city can watch

See Separate Article CCTV (CHINA'S STATE-RUN TV STATION) AND ITS HISTORY AND PROGRAMMING factsanddetails.com

Hunan Satellite Television

Hunan Satellite Television is China’s most popular provincial TV station and second most-watched channel after CCTV. Based in in Changsha, Hunan province and launched in 1997, it features a variety of TV shows and series, including game shows, variety shows and dramas. Young people like it because the shows are fun and there is a high standard of quality. The station is famous for its self-produced programs and entertainment shows such as "I Am A Singer", "Where Are We Going, Dad?", “Happy Camp” and "Day Day Up" (“Tiān Tiān Xiàng Shàng”) . and cultivating talent like XieNa, a famous anchor in China. “Super Girls” is its most famous show. Its Jinying Cartoon Satellite TV channel is popular among children. Hunan Television was at the vanguard of China’s TV industry boom in the late 1990s and early 2000s and has been a major presence ever since. The station is also called mango TV because of its logo.

Michael Keane wrote: Hunan Satellite Television is well known for its entertainments formats, in particular the talent show Super Girls, a clone of the Idol format. In an interview with Hunan boss Ouyang Changling it becomes clear that the southern broadcaster is not making as much capital as many observers think. Ouyang is critical of the market in China and the waste of resources due to so many look alike satellite TV channels (STVs); he is critical of Beijing’s administrative heavy hand and the need to get approval for each program. [Source: Michael Keane, Professor of Chinese Media and Communications at Queensland University of Technology, Creative Transformations, January, 2013]

“Ouyang also takes aim at the lack of copyright protection in the TV industry, complaining that Hunan’s formats are rapidly cloned by its competitors. This is somewhat ironic when one realises that Hunan’s own success was built on cloning overseas TV formats. In fact, when I was researching TV formats in China in 2005 I was contacted by a Chinese lawyer for the Dutch company Endemol to seek advice about how to deal with Hunan’s blatant infringing of their IP. According to Hugo de Burgh, Zeng Rong and Chen Siming the tune changed when a delegation of Hunan producers spent time at the BBC a few years ago examining the workings of the TV format business.”

Hunan TV Criticized for Putting Ratings Ahead of Political Responsibility

Hunan TV was slammed by Chinese Communist Party (CCP) authorities for placing too much emphasis on high ratings, lacking a sense of political responsibility, and spending too little effort on CCP construction in rectification notice released by the Communist Party’s Hunan provincial committee after an inspection of Hunan Television from February to April, 2017. [Source: Jiayun Feng, Sup China, September 1, 2017]

The notice read: ““For a long time, some leaders in Hunan TV deeply believed that ‘Entertainment is the foundation of a television station’ and that ‘High ratings are the only criteria on whether a television station is successful or not.’ Some channels have been swinging between social benefits and economic benefits. They have failed to fulfill the mission of being a mouthpiece of the Party.” The notice also asserted that on the surface, the problem with Hunan TV seems to be its loose control of several channels and shows, but in fact it reflects the lack of political sensitivity among the TV Party committee.

According to Sup China: “The notice pointed out several TV shows that it said led “wrong directions of public opinions.” Where Are We Going, Dad? , a popular TV reality show that was cancelled due to a government order after four seasons, is blamed for excessive promotion of the children of celebrities. The notice also admonishes a local news program for covering too much negative news and calls for it to increase positive publicity. It also criticizes some other shows for female guests showing too much skin or for advertising fake products. One person posted online: “Since when did ‘mouthpiece of the Party’ become a good word?” Another said: “Too many Korean pop stars are featured in shows produced by Hunan TV. It’s time for it to make some changes!”

FakeTV Ratings in China

On September 15, Chinese director and screenwriter Jingyu Guo created a furor when he exposed on Weibo the prevalence of fraudulent ratings in China’s TV industry. Sup China reported: “According to Guo, it is common practice for TV producers to “buy” fake ratings. The current rates go for around 900,000 RMB ($131,000) per episode, as he learned last year when he was approached by representatives to bolster the ratings of his show “Mother’s Life” (Niáng Dào). If Guo had agreed to purchase such ratings, his production company would have had to pay 72 million RMB ($10.5 million) for doctored ratings for the entire series. [Source: Pang-Chieh Ho, SupChina, September 25, 2018]

“In recent years, fraudulent ratings has become increasingly prevalent as broadcasters, eager to appease advertisers, have pressured TV producers to buy ratings. Some TV networks, according to Guo, will only agree to air your programs after you’ve spent money to guarantee good ratings. In addition to a desire to lure advertisers with higher ratings, another reason producers may be incentivized by broadcasters to buy fake ratings is the distribution agreements between TV stations and production companies in China. In many of these contracts, broadcasters pay producers a higher sum for the shows if the ratings reach a certain threshold.

“Guo’s post has caught the attention of China’s media regulator. On September 16, the National Radio and Television Administration responded swiftly to Guo’s accusations by promising they would conduct an investigation into this phenomenon, and that it would “deal with this matter seriously.”

Foreign Television Stations in China

Much of southern China — particularly Guangdong and Fujian Provinces — picks up television channels from Hong Kong and Taiwan without cable or satellite dishes. It is estimated that two thirds of the households with televisions in the Guangdong Province receive regular programming from Hong Kong. Many Chinese tune into satellite broadcasts of Star Television from Hong Kong.

Conversely people in Hong Kong and Taiwan can tune into broadcasts of mainland shows. During the stand-off between Taiwan and China before the 1996 Taiwan election China blanketed the airwaves (which can be picked up in Taiwan) with images of the Chinese military exercises.

Most foreign TV shows broadcast in China are from Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea and Thailand. They have to be approved before they are aired and cannot have violent or vulgar content. As of the early 2000s, people in China could pick foreign television channels such the BBC, ESPN, and the Phoenix Chinese Channel. Star TV, owned by Murdoch-owned News Corp., and MTV, owned by Viacom, were broadcast to selected Chinese audiences. Others like CNN and BBC World were broadcast into hotels and residential compounds used foreigners.

In February 2102, China banned foreign television shows during prime time and told local TV stations they could not show too many programs from one region. The State Administration of Radio, Film and Television (SARFT) said that foreign shows could not be aired from 19:30 to 22:00. According to the China Daily newspaper, the "aim is to improve the quality of imported TV programmes". Stations that violate the new rules face "severe punishments", the newspaper reports.[Source: BBC February 14, 2012]

Image Sources: 1) Julie Chao ; 2) Nolls China website, Wiki Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2022