FILM AND THE CHINESE GOVERNMENT

one thing that has been allowed over the years

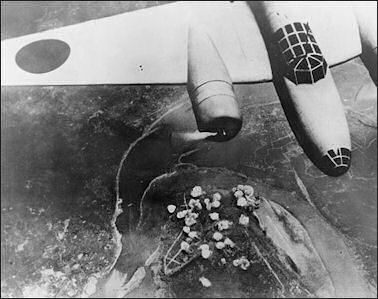

has been films with an anti-Japanese theme China has one of the last remaining Communist film industries. State studios still produce and widely distribute numerous patriotic, propaganda films, known among Chinese film makers as “main melody.” Communist-Party-endorsed films released in the early 2000s included “Mao Zedong in 1925"; “Silent Heroes”, about a couple's selfless struggle against the Kuomitang; “Law as Great as Heaven”, about an courageous policewoman; and “Touching 10,000 Households”, about a responsive government official who helped hundreds of ordinary citizens. By one count more than 20 percent of films, deal with themes linked to the Sino-Japanese war, many made with the aim of strengthening the legitimacy of the Communist government. On the positive side for Japan there are more roles for Japanese actors.

Because of prohibitions, restrictions and meddling, Chinese films are often not very interesting to Chinese let alone an international audience. Chinese movies that have made their way to the West have tended to be martial arts movies or art house films. Chinese directors have managed to produce first rate partly because the government likes to see Chinese directors acclaimed abroad and is afraid of foreign domination in the film industry.

Film scripts must be approved by the China Film Co-production Corporation, the Ministry of Broadcasting, Television and Film and, lastly, by the Ministry of Truth and Propaganda of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. Depending on a number of factors the process can take anywhere from weeks to years. The actual shooting of the film has to follow a strict schedule.

For a long time it seemed that the ultraconservative bureaucrats in cultural ministries seemed be the last holdouts of outdated and unpopular Communist party ideology. Instead of promoting the arts, their aim often times seem to be to kill them, and their methods are often frustrating and arbitrary. Christopher Doyle, a cinematographer that has worked extensively in China, told the Washington Post, "They reinvent the rules every day. The policies shift all the time. It's completely erratic and nobody can trust the government."

The Communist Party has forced people to attend movies. In 2004, entire student bodies of schools of children in the Shenzhen are were forced to see Life Translated, a comedy made by the daughter of high level local party member. The movie was panned by critics. Parents were outraged their children were forced to go.

See Separate Articles: CHINESE FILM factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE FILM INDUSTRY AND MOVIE BUSINESS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE FILM STUDIOS AND MAKING CHINESE FILMS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE-MADE BLOCKBUSTERS AND POPULAR COMMERCIAL MOVIES factsanddetails.com ; WANG JIANLIN AND WANDA: THE BILLIONAIRE AND HIS THEATERS AND FILM PROJECTS factsanddetails.com ANIMATION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HISTORY OF CHINESE ANIMATION AND CLASSIC ANIMATED FILMS factsanddetails.com

Websites: Chinese Film Classics chinesefilmclassics.org ; Senses of Cinema sensesofcinema.com; 100 Films to Understand China radiichina.com. dGenerate Films is a New York-based distribution company that collects post-Sixth Generation independent Chinese cinema dgeneratefilms.com; Internet Movie Database (IMDb) on Chinese Film imdb.com ; Wikipedia List of Chinese Filmmakers Wikipedia ; Shelly Kraicer’s Chinese Cinema site chinesecinemas.org ; Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) Resource List mclc.osu.edu ; Love Asia Film loveasianfilm.com; Wikipedia article on Chinese Cinema Wikipedia ; Film in China (Chinese Government site) china.org.cn ; Directory of Interent Sources newton.uor.edu ; Chinese, Japanese, and Korean CDs and DVDs at Yes Asia yesasia.com and Zoom Movie zoommovie.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Made in Censorship: The Tiananmen Movement in Chinese Literature and Film” by Thomas Chen Amazon.com; “Trickle-Down Censorship: An Outsider's Account of Working Inside China's Censorship Regime” by JFK Miller Amazon.com; “The Contentious Public Sphere: Law, Media, and Authoritarian Rule in China” by Ya-Wen Lei Amazon.com; “We Have Been Harmonized: Life in China's Surveillance State” by Kai Strittmatter, Matthew Waterson, et al. Amazon.com; “Encyclopedia of Chinese Film” by Yingjin Zhang and Zhiwei Xiao Amazon.com; “The Chinese Cinema Book” by Song Hwee Lim and Julian Ward Amazon.com; “The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Cinemas by Carlos Rojas and Eileen Chow Amazon.com; “Chinese National Cinema” by Yingjin Zhang Amazon.com

Government Meddling in Chinese Films

The Eternal Wave Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times, “The government wields a heavy hand over domestic productions and imports, tinkering with scripts, censoring content and barring entire genres. Recent regulations include bans on scenes depicting excessive drinking and smoking and plots that denigrate revolutionary heroes and government officials. Another guideline warned television producers to steer clear of dramas employing time travel. Such shows, the State Administration said, “casually make up myths, have monstrous and weird plots, use absurd tactics, and even promote feudalism, superstition, fatalism and reincarnation.” [Source: Andrew Jacobs New York Times July 17, 2011]

Hong Kong director and producer Manfred Wong told the Shanghai forum that in crime movies made on the mainland all police officers must be portrayed as good guys, while romantic movies cannot show affairs or cohabitation before marriage. Edward Wong New York Times, “The Chinese Communist Party has always viewed film as perhaps the most powerful medium for swaying the opinions of the masses, and used it for decades as a propaganda tool. More recently, the state has identified the film industry as critical for shaping China’s image abroad. Its levers of control within the industry have grown subtler. Directors who produce unauthorized films that overtly challenge the government can face temporary work bans or more serious harassment. But more often, officials rely on the acquiescence of directors who seek to reach a broad audience. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times August 13, 2011]

China does not forbid independent filmmaking, but it does control distribution, so filmmakers who want their work to be widely seen end up submitting themselves to a capricious censorship process. Access to a lucrative domestic market is at stake, and government support can help international sales, so censors have become gatekeepers to money and fame. The drive among prominent directors to expose uncomfortable truths appears to have diminished as the country has grown wealthier. Once-rebellious artists, like the director Zhang Yimou, have been showered with largess after agreeing to work within the system they once disdained.

Chinese Film, Politics and The Internet

Xiang Yong, deputy director of the institute for cultural industries at Peking University, said the government was financing film for political as well as commercial reasons."It is sometimes said that Hollywood is the real foreign ministry of United States, which shows how important the movie industry can be to a country," he said. "China currently has very few high quality films that can make it overseas. So from a cultural perspective, the promotion of the movie industry is an important means of strengthening the 'soft power' of our country."

Qiang Zhongyuan, a director at the Beijing Forbidden City Film Company, noted in 2011 year that government policies have helped moviemakers to more than double the budgets they had two years earlier. "Now we can go for big productions of 30 or 40 million yuan [£3m-£4m]. Some even as much as 100m yuan," he said. "These are the benefits we get from the government's policies, which are aimed at strengthening cultural industries and 'soft power'." [Source: Jonathan Watts and Justin McCurry, The Guardian, December 15, 2011]

Zhang Xianmin. Professor of Beijing Film Academy, wrote: In terms of its influence on the world wide web, Chinese cinema can be said to exert more influence in the international market before finding a place in its domestic market. Majority of international audience is not interested in Chinese cinema. The interest flows in one direction only. Chinese-language netizens are quick to produce subtitles for newly released films; they share these subtitles with others. However, there is not a single influential Chinese film critic in the English-language world, and there is literally no one interested in supplying subtitles for our domestically produced blockbuster “The Founding of a Republic”. In the English-language world, Chinese-language films hardly exist. As for what I said earlier about the relationship between the international and the domestic markets, there are some Chinese viewers who risk climbing over the great firewall of China to watch Chinese-language documentaries that are banned in China.

In 2005, I asserted that Chinese cinema did not have political films but only subservient films and art-house films. If politics are detected in any art-house film, it must have ended up so in secret. At that time, only three to four filmmakers dared to embed explicit political messages in their works. However, the number of people who dare to do the same has increased exponentially over the past few years because of a series of social changes and ironically too, the ever stricter censoring going on in the Internet. After a certain event takes place, videos that document it are edited fast and put on the Internet for immediate viewing (the fastest that I have seen is a next-day release). These videos vary in length. They share a common disregard or disrespect for copyright issues, which are capitalist in nature. They use streaming technology. As compared to the dissemination of their content, their form matters little if anything at all. Their purpose is to have as many people as possible watch them and take immediate actions. These filmmakers do not care if their works are films. Some of the longer videos or feature-length films are produced by professional filmmakers, who do not submit their works to any film festival. They do not need anyone to assess the artistic value of their works. The names of these people are sensitive search words in China. Puzzled readers can try to do a search of them by first climbing over the great firewall of China.

Censorship in China

Shang Gan Ling China has a vast censorship apparatus. Films and television programs are particularly tightly controlled. One film director told the Guardian that

censors demanded 400 changes before they would pass his movie.

Film Bureau at China's State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television (SAPPRFT) is the main regulator and censor of films. In 2010, a total of 526 films it had approved were made. The organization sued to be called the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television, also known as SARFT,

Television shows and films are approved and censored by the various government agencies. Taboo subjects include explicit sex, nudity, graphic violence, gambling, adultery, ghosts and criticism of the Communist party. Sometimes films are cut for the oddest reason. On action movie, for example, had a scene removed in which a policeman is zapped to death by an electric eel in a swimming pool because it depicted a "unrespectable" way to die. Films that please the censors often turn out to be yawners that no one is interested in seeing.

There has traditionally been no rating system. A film made in China has be acceptable to people of all ages, including children. In recent years there has been some discussion about starting a rating system. Theoretically under such a system more sex and violence would shown is films given an dual rating but it is unclear how much.

Films are often censored for showing some of the harsh realities o Chinese life: men gambling in messy rooms, people cleaning their bed pans in the street, The censors feel that this reveals the undeveloped, negative side of China and would be damaging to China’ reputation abroad. Films that deal with contemporary problems such as corruption, land grabs and environmental problems are also sure to get axed.

The Chinese director Jiang Wen said that dealing with censors “is all too much like a Hitchcock thriller. There is terror all around me, but I can’t see what’s going on.” A common ploy used by censors is to tell a director that his film can not be approved and cuts have to be made. But then they refuse to more specific. The producers have to make the changes themselves and bring the film back and go through the same process again.

One critic compared the process of making a film in China to the ancient Chinese torture of "death by a thousand cuts." Many directors refer to the censors as “Edward,” a reference to the film “Edward Scissorhands”. In 1996 and 1997, the process of getting a film approved became tougher, when authorities announced that filmmakers should produce more films than depict socialist ideals and that Communists would keep an even more watchful eye on the Chinese film industry. After the directives were issued the number of Chinese films made was reduced by half.

Most films that are banned are easy to pick up on a pirated video or DVD. In many cases when something is banned or censored it creates a bigger market for it. Chinese, like most people, are often attracted to what is forbidden, and there are plenty of producers of pirated material to fill demand.

Examples of Censorship in China

NRA tank fighting Japanese in 1937 Parts of “Mission Impossible III” had to be cut that showed laundry hung out to dry Scenes from “Cold Mountain” were cut because they were too ‘spicy.” “Rush Hour 3" was banned because of depiction of a Chinese organized crime family. A commercial for an electronic company with Arnold Schwazenegger was banned by government censors because Schwazenegger’s movies were deemed too violent. When the electronic company tries to breach its contract with Schwazenegger, the actors law firm threatened to seize the company assets. The firm settled with Schwazenegger.

In 1995 the film "Relations between Man and Woman", by director Feng Xiaogang, was censored by the Ministry of Radio, Film and Television because it chose sexual promiscuity and drug addictions as subject matter rather than "exemplary communist lifestyle." The screenwriter rewrote the script so it would pass. The showing of “Cape No. 7", a highly successful Taiwanese film, was blocked in mainland China because it portrayed the Japanese before World War II in a positive light.

In 1997, Chinese authorities prevented Zhang Yimou and Zhang Yuan from attending the Cannes Film Festival. Zhang Yuan had his passport seized because his banned-in-China film “East Palace, West Palace” depicted gay life in China. Zhang's comedy, “Keep Cool”, was kept out the Cannes competition because Chinese authorities said the film was not ready, which was not the case according to Zhang's agent. "Eat Palace, West Palace" is gay slang for two public toilets where gays meet on either side of the Forbidden Palace in Beijing. Lou Ye One was banned from making films for five years because he showed his film "Summer Palace" at the Cannes Film Festival without government approval. The film features sexually explicit love scenes set against the Tiananmen Square protests. The Xinhua news agency said the film would be confiscated and money from ticket sales confiscated.

Censorship is easing. now. Films banned six or seven years ago are now allowed t be shown. The film “Troublemakers”, for example, which depicts corruption in rural areas was approved in 2005 after being reject in 2000.

How Chinese Censors Work According to the Global Times

The Global Times is a mouthpiece of the Chinese government. It reported: “Every Thursday afternoon at 1:30, Liu Huizhong arrives at room 301 in the China Film Archive in Beijing. One day at the end of 2015, he was reviewing the digital versions of two old films with two other censors. One was “Taitai Wansui” (“Long Live My Wife”), produced in 1947. Liu gave the film a score of 62. “"I let it pass," he shouted to his colleague a meter away. After being converted to digital formats, old films usually have technical issues such as black spots and light balance. Part of Liu's job is to ensure these have been taken care of. Of course this is only part of his job as a film censor working at the Film Bureau at China's State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television (SAPPRFT). On two other days of the week, he is responsible for reviewing new films.[Source: Global Times, January 21, 2016]

“As a film censor, Liu is in charge of the destiny of movies in the Chinese mainland as any film that wants a spot in mainland theaters needs to pass SAPPRFT review to get a license: the golden "dragon mark" on a red background. The censor team consists of about 50 people, mostly over 50 years old while the youngest member is in his 30s. The 75-year-old Liu is the oldest of them all.

“As part of the review process for new films, a movie will be viewed by five censors, each giving out a score between 1-5 as well as suggestions on any parts of the film that need to be modified. Any members of the team that hold different opinions are allowed to present their case in order to convince others. If a team cannot reach an agreement, another five censors will be called in to review the film until they agree to approve it, disapprove it or send it back with suggestions on what needs to be changed so the film can be approved. "Only a few are either the best or the worst. Most movies end up stuck at this step," Liu said, joking that while other people spend money to see films, he earns money by watching them. Some people see censors as having great control over films in China, but Liu doesn't see himself that way. In his opinion he is just a cog in the machine, with the real power being held by SAPPRFT.

“Liu graduated from the Beijing Film Academy in 1964 and went to Vietnam to work as a war photographer in 1968. After he returned to China, he started working as a photographer and eventually became a director in 1990s, and then even later a producer. After working as a censor for CCTV's movie channel, he began working as a film censor for SAPPRFT in 2008. "To maintain the harmony of the State, you need to guard it," he told Portrait, explaining that this was a mission that didn't have any quantitative criteria, and completely depends on one's judgment. "If you don't pay attention and don't follow the right rules, you may end up making mistakes," Liu said. To sharpen his judgement, he insists on reading newspapers, watching TV and studying politics, but still feels that his understanding of politics is lacking.

“Political sensitivities are very important when reviewing a movie. When reviewing Qichuan Xuxu (Gasp), a 2009 film from director Zheng Zhong, Liu pointed out that the lighting of Tiananmen Square in some scenes made it look gloomy.

“"It looked just like a scene from old society," but the film was supposed to be a contemporary story. Even though the square only appeared in the background of the movie, Liu could not allow it to pass. He pointed out that there were plenty of days when the square could be seen under a bright blue sky with white clouds, so why had the director chosen such a gloomy day? Presenting his worry that it might have some political implications, he convinced the other censors that the tone was too gloomy and that the scene needed to show the prosperity of modern society. The movie was sent back so the studio could make changes.

Chinese Censors Disapproval Process According to the Global Times

According to The Global Times: “Compared to approving or sending a film back for changes, disapproving a movie is actually pretty difficult. "In the past, we either approved or disapproved a film. Now we suggest how things should be changed." Liu doesn't even like to use the word "disapprove" when talking with his colleagues. When he feels a movie shouldn't pass review, he instead says: "I don't think film is very solid, what do you think?" If everyone feels the same way, then the film is disapproved. However, if he is in the minority, he then submits a report with his opinion. "You need to consider the future of the directors, the investment of the producers, the impact on society and the pressure of public opinion." [Source: Global Times, January 21, 2016]

“Usually when a film is disapproved instead of sent back for changes it is not allowed to be resubmitted for review, but that is not always the case. Once a woman in her 50s shot a 90-minute biography which she funded on her own. Liu disapproved the film when he saw it the first time. "There was no story and no technique. It was badly produced." However, apparently the film had "power" and so was resubmitted to the review board eight or nine times - Liu ended up watching it three times. Though the name of the film and the studio kept changing, the film was still disapproved each time. "I can't sympathize too much. If I passed it, audiences would criticize me saying: 'What the hell is this? How did it pass review?'"

“Much is done to keep outside influences from affecting censors. Censors are assigned films randomly and they don't know what they will see ahead of time. Their suggestions are released as the official opinion of SAPPRFT with no information revealing who was involved in order to avoid communication between censors and studios. Sometimes this review process is even used by studios to market a film. Before Jiang Wen's Gone with the Bullets was released, rumors were flying about a certain part of the film being cut. However, as one of the reviewers of the film, Liu said only two things were changed. Liu said that the rumors were actually a form of marketing, because if audiences heard that the movie was something they were not allowed to see, they would become even more curious about it.

Lou Ye Blogs About His Battle with Censors

Lou Ye, regarded as one of the founders of China’s Sixth Generation of Filmmaking, is known for angering Chinese authorities and battling the censors. His movies often address topics the Chinese government is not fond of such as sex and politics and as a result several of his films have been banned. He was once barred form making movies for 10 years. In 2012, he produced the dark melodrama — “Mystery”, a French-Chinese co-production. After he was told to edit two scenes and cancel the co-production agreement without explanation he took unusual move of blogging about the negotiations and interactions with authorities.[Source: Julie Makinen, Los Angeles Times, October 18, 2012]

Julie Makinen wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “"Mystery" looked like a chance for the director come in from the cold. Lou received approval from China's censorship body before screening his movie at the Cannes. After the festival, he registered the $2.6 million noirish tale, made with 20 percent French financial backing, as an official French-Chinese co-production. But weeks before the opening of "Mystery" in Beijing, Chinese authorities told Lou to edit two scenes containing sex and violence. In China friction between filmmakers and government regulators is a regular occurrence, yet often, the difficult back-and-forth takes place behind closed doors. This time, Lou took the fight public, posting documents online and blogging for weeks about each interaction and negotiation with authorities. The skirmish raises unsettling questions about Chinese officials' willingness to scuttle business deals and impose new censorship requirements, even after issuing approvals.

“"Mystery" centers on a wife's discovery of her husband's affairs, and touches on some potentially sensitive subjects like the behavior of police. In his postings on Sina Weibo — the Twitter of China — Lou said officials had asked him to reduce the number of hammer blows in one bludgeoning scene from 13 to 2.“"This is the Chinese way. It's not good, but this is the way," Kristina Larsen, the French producer on "Mystery," said in a phone interview from Paris. "Basically in France, no one wants to go into co-productions with China — you have this different culture, and all the censorship. It's too complicated."

“After two weeks of negotiations, Lou was able to declare a victory of sorts: He agreed only to darken the final three seconds of the bludgeoning sequence. And, to voice his displeasure, he said he would remove his name from the credits on the film — though it still appears on posters and other promotional materials.

How Censorship Prevents Chinese Versions of Kung Fu Panda From Being Made

The East is Red Films in China are expected to maintain certain standards. Men are expected to be handsome and strong. Women have to be graceful and demure. Teachers have to be respected. A central character that is lazy, dirty or has other flaws, even if they are corrected as the film progresses, are not tolerated. A film executive said, “All the censors can think about is how to teach children...And they can’t seem to understands that edgy, hip entertainment can actually result in some pretty effective teaching.”

On the frustration he felt when almost of his scripts for cartoons about the Olympics mascots were rejected, the film director Lu Chuan told the Los Angeles Times, “every character had to be perfect. You couldn’t have violence or blood, which meant no confrontation or drama. It was impossible to create anything. In the end, I didn’t want to waste two years of my life on this propaganda, so I quit.”

The film “Kung Fu Panda” was a big success in China — the most successful animated film of all time there. There was a lot of hand ringing in China over why Hollywood could make a popular film about China’s most famous animal and sport and China couldn’t.

Explaining why Hollywood could make a popular film about China’s most famous animal and sport and China couldn’t, Stan Rosen of East Asian Studies Center at the University of Southern California told the Los Angeles Times, “Given the political overlay, it becomes difficult in China to make movies, if you start off with a fat, lazy panda, a national symbol, someone is bound to come along and say, “We can’t give an image te world ha the China is fat and lazy.”

Loosening of Film Censorship in China

In 2003, the government began looking at film as more of industry and a way to make money than a propaganda device and started allowing banned film makers to make films and streamlined the censorship process, requiring them to submit 1,500 script proposals for approval rather than script itself. Censorship is not what it was. Director Lou Ye was banned from making films for five years beginning in 2006 after he submitted “Summer Palace”, a sexually-explicit drama set during the Tiananmen Square demonstrations, to the Cannes Film Festival before receiving government approval. Despite the ban Lou made “Spring Fever,”, which was screened at Cannes in 2009. The government is increasingly not touching films on previously taboo subject like the Cultural Revolution, Tiananmen Square and the Anti-Rightist campaign of the 1950s. Many intellectuals feel these subjects need to be addressed because people are beginning to forget about them and the younger generation doesn’t even know they happened.

Filmmaker Jia Zhanghe told the New York Times: “The censorship process has changed a lot. I think the biggest change happened in 2004. After 2004, from my own perspective, from the perspective of someone who works in the film industry, there was more discussion in the censorship process. In the past, no one came to talk to us. They would just say “yes” or “no.” No one would listen to the director, no one talked to the director about why he or she made the film or why he or she dealt with the subject in this manner. After 2004, directors began to have the opportunity to discuss and express their own views. After 2004, the range of subjects that directors could make films about also expanded. Of course, it’s not at the point we’d like. But I’ve always believed that we must encourage progress of China’s system. If China makes progress, then we must recognize it. The censorship process has slowly become more relaxed. [Source: Interview with Edward Wong, Sinosphere blog, New York Times, October 18 and 21 2013]

“At the same time, we can’t forget the power of China’s cultural conservatism. It’s not official, it doesn’t come from the government. It comes from the people. For example, “Django Unchained” by Quentin Tarantino. “Django Unchained” was initially approved. It played for one night and then it was halted because there’s a scene in the movie with a naked man. Why did this happen? Because there were some conservative people in the audience who wrote letters and made phone calls to report it. So if we’re looking at what’s blocking the progress of Chinese society, we can’t just look at official controls. It also has to do with the Chinese people themselves.

In 2004, there was a change in that China wanted to develop its film industry. It became more commercialized. The change was very big, because they began to look at films as an industry. Before, films were seen as propaganda tools, just like CCTV or People’s Daily. After 2004, in order to build up the Chinese film industry, officials began to see films not as simply propaganda but as an industry. This change in thinking directly led to the relaxation in policies that came about later.

On his experience with “A Touch of Sin”, which seemed to clear the censors with relative ease but was ultimately blocked from being shown in mainland China, Jia said: “After the film was submitted to the censors, we waited 20 days, and they came back with two pages of orders and suggestions. The screenplay had already been approved before that. There weren’t really any problems with the script. The two pages were for the finished film. I felt like it wasn’t too bad. They are trying to change as well. They waited two to three weeks after the first edit was submitted to the censorship board, and then they came back with the two pages. And then we resubmitted the edited version. We waited for about a week, and it was approved. It was approved before the final list of films selected for the Cannes film festival was released, otherwise it wouldn’t have complied with regulations.

“Regarding the violence, they asked me if I could take out some of the violent scenes, and I wrote back to them saying this is the point of the movie. If I take them out, then I don’t know what we’re discussing [in the film]. They had suggestions, and then they had things I had to do. Like in the scene where they have the welcome ceremony at the airport, there was a reference to something about harmony and they said I had to take this out. I thought this was no loss to my film, so it wasn’t a problem." When asked if he knows who the censors are, Jia said: I do know some of the censors, because some of them are professors or movie critics. Most I don’t know."

2018 Memo on Tighter Regulations on Film and TV Dramas

In 2018, a memo Chinese), obtained and shared by WeChat blogger Xiaode Zhang, allegedly from the government media regulator SAPPRFT, encouraged content that showcases “people’s happiness” and then provided a long list of what wasn’t acceptable. [Source: Jiayun Feng, Sup China, June 12, 2018]

SupChina reported: “Types of content that are discouraged or subject to extra scrutiny include history, the military, and revolution. Creators are forbidden from making “subversive adaptations” of historical events and content should be in line with the official narratives of historical figures. Creators are also advised to focus on lives of average people and avoid broad issues of social order and the national situation.

“Some other regulations include: 1) Don’t glorify the Republic of China, the Beiyang government, and its warlords.2) Coming-of-age stories should avoid romance, crime, and violence. 3) Crime stories need to get approved by the Ministry of Public Security and may not contain too many details about the crime. 4) Celebrities who have been caught in drug or sex scandals should not be featured. 5) Homosexuality is respected, but gay-themed content or gay characters are not allowed. 6) Don’t promote weapons or wars. Don’t depict Western countries as imaginary enemies. 7) Stories can be adapted from games, but game players cannot be main characters. 8) The memo also encourages self-censorship. “To avoid potential risks of being censored, ask friends to review your work first,” it says.

Hollywood and Chinese Censors

Michael Cieply and Brooks Barnes wrote in the New York Times: The lure of access to China’s fast-growing film market is entangling studios and moviemakers with the state censors of a country in which American notions of free expression simply do not apply. Whether studios are seeking to distribute a completed film in China or join with a Chinese company for a co-production shot partly in that country, they have discovered that navigating the murky, often shifting terrain of censorship is part of the process. [Source: Michael Cieply and Brooks Barnes, New York Times, January 14, 2013]

“Billions of dollars ride on whether they get it right. International box-office revenue is the driving force behind many of Hollywood’s biggest films, and often plays a deciding role in whether a movie is made. Studios rely on consultants and past experience — and increasingly on informal advance nods from foreign officials — to help gauge whether a film will pass censorship; if there are problems they can sometimes be addressed through appeal and subsequent negotiations.

“But Paramount Pictures just learned the hard way that some things won’t pass muster — like American fighter pilots in dogfights with MIGs. The studio months ago submitted a new 3-D version of “Top Gun” to Chinese censors. The ensuing silence was finally recognized as rejection. Problems more often affect films that touch the Chinese directly. “Any movie about China made by outsiders is going to be very sensitive,” said Rob Cohen, who directed “The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor,” among the first in a wave of co-productions between American studios — in this case, Universal Pictures — and Chinese companies.

“Hollywood as a whole is shifting toward China-friendly fantasies that will fit comfortably within a revised quota system, which allows more international films to be distributed in China, where 3-D and large-format Imax pictures are particularly favored. At the same time, it is avoiding subject matter and situations that are likely to cause conflict with the roughly three dozen members of a censorship board run by China’s powerful State Administration of Radio, Film and Television, or S.A.R.F.T. In addition, some studios are quietly asking Chinese officials for assurance that planned films, even when they do not have a Chinese theme, will have no major censorship problems.

See Separate Articles FOREIGN FILMS IN CHINA: QUOTAS, MARKETING, SUCCESSES AND COMPETITION CHINESE FILMS ABROAD factsanddetails.com ; HOLLYWOOD AND CHINA: STUDIOS, CENSORS AND POPULAR FILMS factsanddetails.com

How Youku Film Streaming Is Helping China's Filmmakers

In January 2012 The Guardian reported: In a country where what's shown on screen is guarded by the government, online video websites such as Youku and Tudou are revolutionising the way people view film and television. In 2010, the number of Chinese watching video online was 284 million. By the end of 2012 the figure could pass 445 million, according to CMM Intelligence, a Beijing-based market research firm. [Source: The Guardian, January 24, 2012]

"After so many years of economic growth, China is ready for similar growth in entertainment," says Jean Shao, a Youku spokesperson. Though Youku offers a YouTube-style user-generated platform, it's now luring viewers from bland state-controlled television and cinema by importing programmes from the west or creating its own content. "China is an immature market comparatively, so when we prepared to launch Youku Premium [the pay-per-view service Fox is using] we thought it would take a long time to get attention", says Shao. "We were surprised." Launched a year ago, Youku Premium has had over a million transactions, with the number of viewers tripling between the second and third quarters of 2011.

Competition for dominance of the online video market is rife, perhaps unsurprising for an industry where total revenue increased by 139 percent from 2010-2011. The two market leaders Youku.com Inc (who have 25.6 percent of the market) and Tudou Inc (14.5 percent) are currently locked in a court battle accusing the other of pirating content. Squabbles aside, online platforms are opening up opportunities for filmmakers that cinematic release would stifle. "Our biggest priority is to have as many people as possible watch our films", says Xiao Yang, one half of film-making duo the Chopsticks Brothers, whose debut short film Old Boys has been watched by 42 million people. "If Old Boys had only been shown through traditional channels, both budget constraints and the plot would have affected the number of people who saw it. On the internet it came alive."

For film-makers wanting to release in theatres, there are substantial censorship considerations. Last month the state council of legislative affairs drafted three new rules to add to the list of ten cinematic no-nos?, which are designed to "promote the prosperity and development of the film industry and enrich the cultural life of the people" — banning the promotion of drug use, hurting people's religious feelings and "playing up" horror, among others.

"We wanted to make a film that might have challenged censors, and if that was the case we were shutting ourselves off from television and cinema" says Melanie Ansley, producer of Red Light Revolution, a Beijing-based comedy about a cabbie who opens a sex shop — content too racy to pass China's cinema censors. After release on Tudou last week, the Chinese-language film has had over 1.2 million views. "I think the internet offers a place for stuff that takes a little more risk," says Ansley. "Some of the comments from viewers of our film say 'how did this get past the censors? I can't believe that I'm watching this, that this is up on Tudou'. "I don't know what the tipping point is, but thinking practically there will be a day when [the government] will move in", says Ansley. "But when that day is none of us know."

Hollywood has long been eyeing the moneymaking potential of China. In January 2012 month 20th Century Fox found a route in to the world's third largest film market, forging a landmark deal with Youku — to stream 250 films to China's 400 million online video viewers.

Need for Rating System to Ease Censorship

The East is Red According to the New York Times: China does not have a movie ratings system like those in the United States or Europe that would give viewers a chance to judge in advance whether a film is too violent for children or teenagers. It relies instead on the brute force of censorship: movies and television shows either have scenes excised or are banned entirely. “The absence of a ratings system “means the movies on screen need to be suitable for kids — that issue has been debated for years,” said Henry Siling Li, a media specialist at the China Executive Leadership Academy of Pudong, an elite school in the Shanghai area for training rising stars in the Chinese Communist Party. “We have to remove nudity and violence from movies” as long as there is the possibility that children will be in a cinema when a movie is shown, he said. [Source: Gerry Mullany, New York Times, April 11, 2013]

Tania Branigan wrote in The Guardian, Hong Kong director and producer Manfred Wong He argued that mainland film-makers need a ratings system. Some believe the government might relax constraints if age restrictions were introduced. But Li Hongyu, who writes about film for Southern Weekly newspaper, said it was simplistic to suggest a ratings system would result in less censorship. While western ratings systems focus on issues such as violence and pornography, China has much wider concerns about the content of films, he said. "China's control over movies is more detailed. China has a movie censoring committee composed of approximately 30 or so staff whose backgrounds are very diverse, spanning from movie professionals, the Women's Federation, the [Communist] Youth League, teachers, and a religious committee to various governmental administration departments," Li added. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian June 16, 2011]

"The debate about introducing a ratings system has been going on for many years. But it is hard to implement, since if the system is used, it will not be easy to cover the government's other considerations. What if it is concerned about political views?" Official requirements, which concern the moral as well as political qualities of content, can be baffling to outsiders: the head of the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television recently denounced TV time travel dramas for their "frivolous" approach to history.

Film Criticism in China

Film criticism in China, Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “remains a practice stunted by corruption and bribes, state censorship and the culture's emphasis on personal connections, or guanxi, that makes penning negative reviews hard to do. Consumers aren't in the habit of reading reviews, in part because they are attuned to the fact that the government, and filmmakers, work to ensure only articles they endorse see the light of day. As such, the young and tech-savvy are increasingly turning to online forums, where outspoken views are easier to come by. Registered users on Douban, China's largest website devoted to movie, music and book reviews, topped 53 million in 2011.[Source: Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore, Los Angeles Times, March 11, 2012]

"Most Chinese audiences just go the cinema randomly. Few of them read critics before they choose" what to watch, said Li Hongyu, a film reporter for the newspaper Southern Weekly who also pens a weekly movie review column for the Chinese-language edition of Time Out Beijing. Li believes the lack of a robust criticism culture is holding China's film industry back. But there's a lot to change before that can happen, he said.

A Chinese critic living in Denmark founded Cinephilia.net, a website inspired by Rotten Tomatoes that translates Western movie reviews into Mandarin and republishes reviews from Chinese media written by local critics. Above all, the Web provides a platform where cynical "netizens" can give honest opinions about the arts. (Movie fans are by no means alone in this; authors who are heavily censored in print also often find opportunities online. When novelist Murong Xuecun, whose stories often deal with corruption, was barred from giving a speech he had prepared on the absurdity of censorship at a literature award ceremony in 2010, the author published it on his blog instead.)

On Mtime, a major ratings and review website, discussions are candid. "What is missing in Chinese movies compared with imported ones?" asked a group calling itself the "Moviekissers" in 2010. "China is a socialist country. Worship for the superhero or individual hero is not allowed. It has to have a sense of collectivity. Movie heroes such as Batman or Spider-Man will be turned into national leaders in Chinese movies," raged one commentator under the name Booof. A slavish imitation of Hollywood movies, state censorship, commercialism and an emphasis on depicting the "harmonious" society peddled by the government in movies over real social criticism were also cited as flaws.

"For young people, the Internet is the most influential channel [to discuss movies] because anyone can get access to share and spread information," said Ye Xindai, 28, who writes under the pen name Mu Wei Er and is one of China's few recognizable movie critics, with more than 42,000 followers on Douban. Ye makes a living writing freelance for publications ranging from the Southern Metropolis Daily to the Economic Observer.

But the Web is not always free from censorship. When the film "Beginning of the Great Revival" was commissioned to mark the 90th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party last year, Douban and Mtime disabled their star rating system and user reviews. The move was an apparent attempt to squash sardonic comments from Internet users about the historical epic, which was seen as heavily propagandistic. Li believes China's film industry can only mature and improve if a more robust critical culture develops, free from corruption and censorship. "Now there are too few good films in China, and of course it's related to censorship," he said. "If Chinese filmmakers can create more freely there will be more good films. If there are more good films, film critics will be more and more popular. And then more and more people will like the art and will think about the film, rather than just see it as entertainment." "That is the future," he added with a resigned sigh, looking unconvinced that change will come. "It's crazy when China is becoming the biggest film market in the world."

Film Criticism and Discreet Bribes in China

Reporting from Beijing, Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore wrote in the Los Angeles Times: ‘sitting in a trendy cafe in downtown Beijing, he recounts a joke about one particularly hard-to-please former critic. The critic (now a scriptwriter) was known for his scathing reviews of the often poor movies pumped out by the country's film industry. At premieres, the critic, alongside other reporters, would be slipped a hong bao — or red envelope containing cash — by the production company in an attempt to buy a good review. "The joke was like this: The film company told him if you write a film criticism, we'll give you 1,500 renminbi [about $238] — but if you don't write one, we'll give you 3,000," Li said with a despairing chuckle. [Source: Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore, Los Angeles Times, March 11, 2012]

Li says he doesn't accept hong bao. But the pressure hasn't stopped there. Li recalled that in 2003, he wrote up an interview with Wang Xiaoshuai for Southern Weekly whose art-house film "Drifters," about a down-and-out Chinese returnee from the United States, was being screened at the Cannes Film Festival. On press day, the piece was pulled after orders from "up there," Li said, gesturing with one hand toward an unseen entity. Some 40,000 or so papers that had already been printed were pulped. And in 2002, Southern Weekly published a two-page piece inviting cultural critics to comment on Zhang Yimou's hit "Hero" — and many criticized the blockbuster. Li heard later that Zhang "was not happy."

Southern Weekly is known for its daring reporting, like many Chinese newspapers it contains scant movie criticism. Instead, it focuses on film news and big-shot interviews. Most Chinese media organizations do not have a staff movie critic, and many publications that do print reviews use underpaid freelancers, who regularly accept red envelopes of cash from filmmakers, ostensibly to cover expenses.

"It's totally commercialized," said Zhang Ling, a critic completing a doctorate on film at the University of Chicago. Her Chinese-language cinema and culture blog on Chicago, written under the pen name Huang Xiaoxie, has more than 371,000 followers. "Film firms and marketing agencies have started giving out large gifts — so if an envelope contains 1,000 renminbi and you moderately like the movie, you hype it. Right now, Chinese film criticism is controlled by power and money."

The result, as Beijing Film Academy professor Zhang Xianmin pointed out in an influential essay titled "Daytime Booze, Nighttime Party: Thoughts on the Present State of Chinese Cinema," is that "people no longer have faith in film criticism." But a handful of movie enthusiasts, independent filmmakers and writers are campaigning for change. Last year, Jia Zhangke, a leading Chinese director whose film "Still Life" won the Golden Lion at the 2006 Venice Film Festival, declared on China's largest micro-blogging site Sina Weibo that he had raised more than 1 million renminbi to sponsor good film criticism.

Raymond Zhou: Beijing's Answer to Roger Ebert

China Daily film critic Raymond Zhou gained fame by writing Western-style film critiques for Chinese moviegoers and has managed to keep his job and integrity while navigated through the China’s fickle and sometimes hostile state-run film industry. Reporting from Beijing, Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “Raymond Zhou became China's most famous film critic by happenstance. It was 2001, and his work as the editor in chief of a bilingual high-tech website in Silicon Valley had been halved. With extra time on his hands, and unemployment looming, Zhou started writing Western-style movie reviews and sending them back to his home country. The casual, chatty and accessible style — then utterly new to China, where musty academic film criticism was the norm — was a hit. Over the year, Zhou reviewed about 100 new films, from Ridley Scott's "Black Hawk Down" to Steven Spielberg's "A.I." The reviews were published on the Web portal NetEase and Movie View, the most widely distributed film magazine in China. Just a year later, Zhou's reviews were collected into a volume published under the title "Live Reports From Hollywood." [Source: Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore, Los Angeles Times, March 11, 2012]

"I wrote a typical movie review that you would see in the Guardian and the L.A. Times that was why I gained popularity so fast. Nobody had written movie criticism like I did, when I did, in China," said Zhou, who first came to the U.S. in 1986. Today, Zhou is the closest China has to a Roger Ebert-type personality. In addition to his day job as a reporter at the state-run newspaper China Daily in Beijing, he's the author of a series of seminal Chinese books on Hollywood and remains a key contributor for Movie View, where he has been a columnist for more than a decade. Still, there are many things that he cannot — or will not — write, as the risk of isolation from the industry is too great.

"The one compromise I have not made, and I have made a point not to make, is that everything I do write represents my honest opinion. But there are a lot of things I don't write. I don't have the freedom. [It's] like my hands are bound invisibly. If you meet a film director, it's very hard to write a bad review. Chinese society functions on connections."

Zhou said he has felt the constraints of the industry firsthand, largely because of his refusal to accept hong bao. "Zhang Yimou's handler told me [later] that they deliberately excluded me in their press screening for 'A Woman, a Gun and a Noodle Shop,' which later got widely and vehemently panned by critics," Zhou said. "I guess they knew it's a bad movie and there's no chance I would write glowingly about it."

China’s Critics of the Critics

In 2017, Lilian Lin wrote in the Wall Street Journal’s China Real Time: “Amid a surge in film and TV critics working exclusively online, the state-backed China Film Critics Association has named a 19-member committee to guide “the healthy development of online film and TV critics.” The association, comprised primarily of established critics and academics, said it was not trying to censor the work of online colleagues, some of whom have gained large followings. “The new group was empaneled after negative reviews of two new films, “Great Wall” and “See You Tomorrow,” which have powerful Chinese backers. The state-sponsored People’s Daily recently opined in an online edition that “malicious bad reviews” could devastate “the ecosystem for Chinese films.” [Source: Lilian Lin, China Real Time, Wall Street Journal, January 17, 2017]

“In one instance, an online critic who goes by the name “Profaning Film” said “Great Wall” was marred by weak characters, “a bad story and lack for imagination” and that its director was washed up. After the review ran, the state-sponsored China Film News criticized Profaning Film, saying the critic was “treading the bottom.” “Profaning Film has about 960,000 followers on the Twitter-like Weibo platform. Profaning Film did not respond to requests for comment, and the critic’s actual identity could not be determined. “Great Wall” is a China-U.S. co-production whose backers include the state-supported China Film Group, Dalian Wanda Group’s Legendary Entertainment and Le Vision Pictures, a unit of the internet company LeEco.

“People’s Daily and China Film News have also criticized the credibility of online film site Douban.com, after its aggregate of consumer reviews gave “See You Tomorrow” a measly one star out of a possible five. The film was produced by Alibaba Pictures, the film arm of the internet giant Alibaba Group.“A Bei, the founder of Douban.com, said in a response posted onlinethat the company would accept “conducive criticism” and would continue to work on providing fair star ratings.

“Reports of the new critics panel in Chinese news media have led to a backlash on social media, with one commentator saying that it could hinder Chinese film development by shielding it from critiques that could help filmmakers improve their art. “Negative reviews would not hinder films from developing, but not allowing negative reviews would,” said one user on Weibo. In response to the dustup, online film critic Mu Weier resigned from the panel, saying he was tired of being vilified by, well, critics. He apologized to his readers.“Writing film critics should be responsible to no individual or institution,” he said in a statement he posted online.

Image Sources: Wiki Commons, University of Washington; Ohio State University ; Global Times Chinese: photo.huanqiu.com

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021