CHINESE DANCE

Sleeve dance Dance in China appears to have grown out of religious rituals and has a long association with theater and the martial arts. Most forms of traditional dance survive in Chinese opera. Many stylized martial arts movements also feature elements of dance.

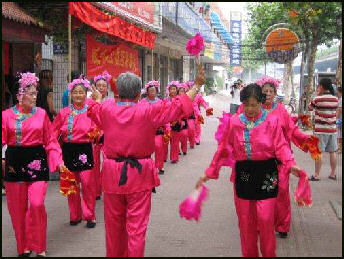

Exercise dancing is a common sight in public squares in Chinese cities when the weather is warm. It is typically done in the morning to fairly loud taped music, often old Maoist-era revolutionary music, or more upbeat techno pop. The participants are usually retired or elderly females although men sometimes join in.

Dr. Emily Wilcox. Associate Professor of Chinese Studies, Director of the Chinese Studies Program, and Chair of the Department of Modern Languages at the University of Michigan, is one of the main experts on Chinese dance. “Revolutionary Bodies: Chinese Dance and the Socialist Legacy” by Emily Wilcox (University of California Press, 2018) is the first English-language, primary-source- based history of concert dance in the People’s Republic of China. Combining over a decade of ethnographic and archival research, Emily Wilcox analyzes major dance works by Chinese choreographers staged over an eighty-year period from 1935 to 2015. Using previously unexamined film footage, photographic documentation, performance programs, and other historical and contemporary sources, Wilcox challenges the commonly accepted view that Soviet-inspired revolutionary ballets are the primary legacy of the socialist era in China’s dance field. The digital edition of this title includes nineteen embedded videos of selected dance works discussed by the author.

See Separate Article MUSIC, OPERA, THEATER AND DANCE factsanddetails.com ; ANCIENT MUSIC IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TRADITIONAL CHINESE MUSIC AND MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS factsanddetails.com ; ETHNIC MINORITY MUSIC FROM CHINA factsanddetails.com ; MAO-ERA. CHINESE REVOLUTIONARY MUSIC factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE OPERA AND THEATER, REGIONAL OPERAS AND SHADOW PUPPET THEATER IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; EARLY HISTORY OF THEATER IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; PEKING OPERA factsanddetails.com ; DECLINE OF CHINESE AND PEKING OPERA AND EFFORTS TO KEEP IT ALIVE factsanddetails.com ; REVOLUTIONARY OPERA AND MAOIST AND COMMINIST THEATER IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The History of Chinese Dance” by Wang Kefen Amazon.com; “Dances of the Chinese Minorities” by Li Beida Amazon.com; “Chinese Dance” by Yuan He Amazon.com; “Chinese Dance: In the Vast Land and Beyond” by Shih-Ming Li Chang, Lynn E. Frederiksen , et al. Amazon.com; “Revolutionary Bodies: Chinese Dance and the Socialist Legacy” by Emily Wilcox Amazon.com; “Red Detachment of Woman: a Modern Revolutionary Dance Drama” Amazon.com “Taking Tiger Mountain by strategy;: A modern revolutionary Peking opera” Amazon.com; ”International Encyclopedia of Dance”, editor Jeane Cohen, six volumes, 3,959 pages, $1,250, Oxford University Press, New York.Chang, Ting-Ting. 2008.Choreographing the Peacock: Gender, Ethnicity, and National Identity in Chinese Ethnic Dance. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Riverside. Wilcox, Emily. 2011. The Dialectics of Virtuosity: Dance in the People’s Republic of China, 1949-2009. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley.Cheng, De-Hai. 2000. The Creation and Evolvement of Chinese Ballet: Ethnic and Esthetic Concerns in Establishing a Chinese Style of Ballet in Taiwan and Mainland China (1954-1994). PhD Dissertation at New York University School of Education

Early History of Chinese Dance

The earliest forms of dance grew out of religious rituals---including exorcism dances performed by shaman and drunken masked dances---and courtship festivals and developed into a forms of entertainment patronized by the court. In ancient texts there are descriptions of troupes of women dancers entertaining guests at official banquets and drinking parties.

Tang-era sleeve dancer

Images of Chinese dancers have been found on 4,500-year-old pottery. The Book of Songs recorded a dance festivals in the Zhou dynasty (1100-221 B.C.). According to Chinese mythology the cultural hero Fu Xo gave humans the fish net and the Harpoon Dance; the god She Nong created agriculture and the Plough Dance; and the Yellow Emperor, the legendary ruler from the 26th century B.C., is honored with Dance of the Cloud Gate. Ancient texts also mention hunting dances and a Constellation Dance, which was performed to seek help from the gods for a good harvest.

In ancient times, dance was regarded as kind of physical exercise that help harmonize the body and the mind. It was incorporated into Confucian rituals and military exercises. One early Confucian dance called the Great Dance of Zhou featured performers with flutes and pheasant feathers. In

Han dynasty (206 B.C.-A.D. 220) dances included a dance with 16 boys acting out chores performed by farmers such reaping, cutting grass and shooing away birds, and a dance with 300 young girls moving around a sacrificial altar. Bas reliefs and rubbings from the period depict dances with weapons, scarves and long sleeves. The movements that were represented are similar to dance moves still performed today.

By the A.D. 6th century pantomime dances were being performed in dynastic courts. Regarded as the precursors of Chinese theater, they blended stories, songs and dances. The performers wore masks or painted their faces. Early pieces from this genre include a performance based on the legend of Prince Lan Ling and a dance hall-style farce about a drunken wastrel called The Swinging Wife.

Later History of Chinese Dance

In the Tang Dynasty dances and music styles from outside of China were incorporated into Chinese dance and Chinese styles were passed onto other parts of the world, particularly Korea and Japan. Hundreds of young men and women were trained in dance and music at a school called the Academy of the Pear Garden. Tang poets wrote of “the dance of the rainbow skirt and feathered jacket” and described how dancer used their long silk sleeves to accentuate their hand movements. This kind of sleeve dancing was also depicted in Buddhist cave art from this period.

After the Tang dynasty the custom of foot binding began to take root. This was a severe blow for women dancers. It is difficult to walk, let alone dance with bound feet. Dances performed in dance theater and Confucian ritual were the preserve of males. Most of the dance in Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties was associated with theater (See Below).

Western-style social dancing was unknown in China until it was introduced by Europeans in the 19th century. In the 1920s taxi-dance halls, where male customers rented female partners, became all the rage in Shanghai and dance hostesses replaced singsong girls as the main public entertainer. Taxi dancing spread to the United States and it was condemned by conservatives. Dance hostesses were treated by police as prostitutes and students at some universities caught dancing faced expulsion. In 1947 dancing was banned with the aim of “increasing production, maintaining social security and quelling the rebellion of the Communists.” The ban was upheld by the Communists when they came to power in 1949

Chinese Dance in the Early Communist and Mao Era

The Chinese celebrated their early victories by dancing the yang ge (See Below) in the streets. Schoolchildren and students performed the dance in long lines in the streets. Yang ge spread rapidly and became associated with the Communist victories. Dance was widely promoted and utilized for propaganda purposes in the 1950s. A typical dance troupe performed a Lotus Dance, a dance infused with Russian folk-style dance steps, a comical lion dance, a trick wrestling bout and a classical sword dance. Such troupes often served to draw a crowds that were then indoctrinated with some kind of Communist message. These troupes also traveled around the world and later incorporated elements of Cambodian, Burmese, Indonesian and Ethiopian dances.

In a review of the book, “Revolutionary Bodies” by Emily Wilcox, Xiaomei Chen wrote: Dai Ailian was a dance icon in the early days of the People Republic (PRC). Born in Trinidad in 1916 and trained in London as a ballet dancer, Dai moved to China in 1941 during the war period as a rising star with a distinctive style that bridged East and West. Her rival was Wu Xiaobang who initially rejected “new yangge,” a folk mode of revolutionary dance, as lowbrow working-class art, favoring instead his Western approach to modern dance with its higher aesthetic values, only to fully embrace the “new Yangge” movement after he arrived in Yan’an — where the Chinese Communists were based — in 1945. Dai Ailian played a key role in bridging the oppositional approaches of native/Yan’an versus Western/elitist through her own theory and practice of a third approach, which drew inspiration from regional rituals and ethnic dances in order to develop a new form of Chinese art. In 1949 Dai was chosen as the president of the All-China Dance Workers Association over Wu, who was male, her senior, and already a CCP member who had promoted the modern dance movement longer than Dai[Source: Xiaomei Chen, University of California, Davis, MCLC Resource Center Publication, June, 2020; Book: “Revolutionary Bodies: Chinese Dance and the Socialist Legacy” by “Emily Wilcox (University of California Press, 2018)]

Yang ge performance

The years from 1950 to 1952 was kind of hashing out period. The mostly Western ballet dance drama as Peace Dove presented an anti-U.S. imperialism story on pointe shoes which was generally negatively received and stirred up a debate on how to use Western ballet to serve revolutionary socialist themes. Ouyang Yuqian, the director of Peace Dove, said the work was “too traditional” and “out of touch with the tastes of contemporary audiences” whose “expectations for art are relatively high” By contrast, though reviewed as lacking in a polished artistic style, the song and dance drama “Braving Wind and Waves to Liberate Hainan” was well-received because of its realistic portrayal.

The golden age of dance of the high socialist period was in the mid and late 1950s. A massive “lotus dance” — which combined yangge and kunqu with other regional dance steps, around a float trumpeting the “success of socialist construction” in the national parade in 1955 celebrating the sixth anniversary of the founding of the PRC. China was in fact both a producer and a receiver of a lively global dance culture during the Cold War era: in the 1950s and early 1960s, the local and national song and dance performers of the PRC toured around sixty countries and won awards in international festivals and competitions. Wilcox argues that some of these dances “formed an important medium for China’s international cultural engagements and national self-projection during the socialist era” and had in turn helped developed “the first golden age of Chinese dance”. As Wilcox points out, the fact that Chinese delegations brought dance performances to countries around the world during this period revises the conventional view of China’s isolation from the Western world.

There were other influences. The lasting impact of the military-themed dances in ethnic minority style can be seen, for example, in Feng Xiaogang’s 2017 film Youth , which featured a popular Mongolian-style dance titled “Women’s Militia of the Grasslands” . The film’s powerful visual representations of the dance as well as the director’s personal memories of the Cultural Revolution and of the 1979 Sino-Vietnamese War best testify to the impact of ethic military-themed dances in socialist experience and postsocialist art. Fully developed dance drama of this period coincided with the mass movement of the Great Leap Forward, which set a new standard for Chinese dance choreography through the use of Chinese dance movements to engage political and social issues. The same period also witnessed the premiers of the first few large-scale dance dramas that combined socialist themes with the hybrid artistic traditions of xiqu, folk culture, ethnic minority dances, and mythical stories from Magic Lotus Lantern , Five Red Clouds , and Dagger Society.

Dance During the Cultural Revolution and Afterwards

Dance in the Cultural Revolution. was labeled as "bourgeois and decadent" and discouraged. Ballet and Western-style dancing were singled out for particularly vitriolic condemnation. Instead people were entertained with “revolutionary ballets” like “The Red Detachment of Women” and “The White Haired Girl”, both put together under the supervision of Jiang Qing, Mao’s wife and Gang of Four member. Nixon was entertained with a performance of The Red Detachment of Women when he made his historic first trip to China. See Revolutionary Opera. Chinese who grew up in the Cultural Revolution do not know how to dance because dancing then was mostly banned. One factory worker told ABC in 1978, "The Chinese need the right to free expression. But the thing we need most, and things I cherish most, is the right to dance." Many national songs and dances are performed by song-and-dance companies. Men in these companies have traditionally worn military uniforms with hats with red stars and women wore Mao suits. Revolutionary dance troupes wore Bermuda shorts, ballet slippers and peaked caps.

In the review of the book, “Revolutionary Bodies”, Xiaomei Chen wrote: During the Cultural Revolution, Western ballet rose to become a dominant form after years of struggling to become an equal partner with the new Chinese dance. Ballets were elevated to the high status of model theatre, while “other dance forms, particularly Chinese dance, were actively suppressed”. [Source: Xiaomei Chen, University of California, Davis, MCLC Resource Center Publication, June, 2020; Book: “Revolutionary Bodies: Chinese Dance and the Socialist Legacy” by “Emily Wilcox (University of California Press, 2018)]

In the review of the book, “Revolutionary Bodies”, Xiaomei Chen wrote: During the Cultural Revolution, Western ballet rose to become a dominant form after years of struggling to become an equal partner with the new Chinese dance. Ballets were elevated to the high status of model theatre, while “other dance forms, particularly Chinese dance, were actively suppressed”. [Source: Xiaomei Chen, University of California, Davis, MCLC Resource Center Publication, June, 2020; Book: “Revolutionary Bodies: Chinese Dance and the Socialist Legacy” by “Emily Wilcox (University of California Press, 2018)]

As result of “mass education before the Cultural Revolution, Chinese dance, especially ethnic minority dances, remained popular during the Cultural Revolution among propaganda teams; Red Guard performances of musical dance epics such as The Military Song of the Red Guards , for example, in fact imitated their predecessor “The East is Red”. Amateur dance performances, if taken into account, indeed demonstrate how successful the PRC dance education had been before the Cultural Revolution. It was thus not uncommon to see amateur propaganda team performers combining aspects of choreographies of the revolutionary model ballets with those of Mongolian, Tibetan, and Korean folk dances.

The early post-Mao period witnessed a return to the tradition of the first seventeen-years of the PRC. In 1979, large-scale dance dramas and performances such as Flowers and Rain on the Silk Road successfully combined the socialist legacy prior to the Cultural Revolution with traditional themes and classical dance from the Tang dynasty, Buddhist frescoes from Dunhuang, and local and regional sound and dance vocabularies. Compared with other genres, such as huaju, xiqu, and fiction, one might argue that dance culture in the early post-Mao period can be seen as an exception in exerting a more lasting impact on the subsequent reform era; innovative dance performances such as Flowers and Rain on the Silk Road, for example, remain popular in the twentieth-first century, with repeated world tours to more than twenty countries.

Wu Shu

Wushu is a modern, dance-like acrobatic form of kung fu. The martial arts featured in teh film “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” are regarded as forms of wushu. Wushu will debut as an Olympic sport in the 2008 Olympic in Beijing but no medals will be awarded.

Wushu as an organized sport has been around for some time. In the Han era the rules of wushu were written down in manuals used to train military conscripts. The first Chinese Olympic team’sent to the 1936 Olympics in Berlin---included a wushu team that performed before Hitler. Seven-year-old Jet Li was a member of a junior wushu team that performed on the White House lawn in front of Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger in 1974.

Unlike kung fu which aims to remain close to its traditional forms, wushu is constantly evolving, and adding new stunts and movements. Advanced moves include running up a wall and flipping backwards, spinning 720 degrees while doing a tornado kick, and performing a twisting butterfly kick, which looks like something performed by an Olympic diver.

Basic wushu emphasizes doing movements and kicks with a straight back and extended arms or from a crouching position, like Jet Li often does, with the right arm and the palm held up. There are basic straight leg kicks, such as the front and side stretching kick and the outside and inside crescent kick. Gifted students began leaning how to do butterfly kicks after around six months or so of training.

Wu means “military” and indicates skill with combat forms and weapons. In the old days it was a form of military training and a kind of calisthenics. Some forms were designed for physical exercise while others helped train men for hand-to-hand combat or fighting with weapons.

Performance Dancing in China

Duhuang dance

The Qianshou Kaunyin (Bodhisattva with a 1,000 Hands) Dance is a showy dance in which a bunch of dancers stand behind each other, so only the person in front is visible to the audience. The dancers move their arms and hands so that it looks like the person in the front has a multitude moving of arms. In recent years the dance has been performed publicly by 21 hearing-impaired Chinese women who move their hands and arms to the rhythm even though they are unable t hear it.

One of the most dramatic forms of Chinese dance is the sleeve or ribbon dance in which a dancer uses long silk sleeves to accentuate her hand and arm movements, whirling then around like banners or ribbons and snapping them like whips. The opening scene of the film “House of Daggers” features Ziyi Zhang repelling an attack of stones and trying to assassinate a leader with a knife hidden in here long sleeves while doing such a dance.

Extra-long sleeves are associated with Confucian moral conduct, which promoted covering the entire body from sunlight. The sleeves are used as both extension of the hands or are thrown back to reveal sensitive and beautiful hand movements of the dancer. A.C. Scott wrote in the “International Encyclopedia of Dance”, “The long white silk cuffs, the “water sleeves,” are “a functional extension of the ordinary sleeves of an actor’s robe, as much as two feet log, and the sweeping pheasant plumes of six to seven feet, worn in pairs and attached to certain headdresses. These are manipulated while being held between the first and middle fingers of each hand.”

Yang Ge and Folk Dancing in China

China's 56 ethnic groups do thousands of folk dances. The Han Chinese alone have 700 different ones. Popular folk dances include the dragon dance, lion dance, yang ge flower-drum dance, rattle stick dance, land boat dance, dragon lantern dance, peace drum dance and stilt dance. There are many variations of each type of major dance. In the case of the dragon dance, there is the dragon lantern dance, cloth dragon dance, straw dragon dance, section dragon dance, stool dragon dance, paper dragon dance, incense burning dragon dance, carp dragon dance, ox-shaped dragon dance and beheaded dragon dance. The Lantern Dance, or Flower Lantern Dance, is popular in southern China and is known by a number of other names. It features circular movements of the arms and hands, undulating body motions and accentuated lower back movements linked to the movements of a dragon. Ethnic Group Dances, See the Different Ethnic Minorities factsanddetails.com

Old people like to do the yang ge (yangge or yangke) a traditional northern Chinese folk dance accompanied by singing, drums and gongs and featuring colorful fans, which are held over the head. Developed as a fertility dance by farmers planting in their rice fields, it was introduced to all parts of China by the People's Liberation Army as part of campaign to its win supporters in World War II and was popular in the 1950s and allowed in the Cultural Revolution. Today it is most often seen in Beijing and other cities in the north.

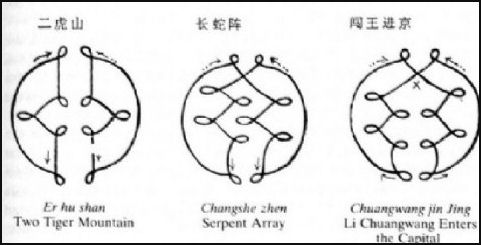

Yang ge patterns

Yang ge is very easy to do. It consists of three quick steps forward, one step backward, pause and repeat, accompanied by hand clapping and swaying movements. In the old days it was performed by male and female dancers facing each other with farm implements such as rakes or hoes, and accompanied by call-and-response singing between the males and females. The dances movement were often sexually suggestive. In World War II, the Communists replaced farm implements with rifles and flags. After the they came to power a number of yang ge troupes were organized and children who showed talent for dancing were recruited and trained for these troupes, which were used to convey political messages to the general public. In many parts of China, yang ge performances were weekly events, with some productions lasting four hours or more.

In the mid 1990s yang ge experienced a dramatic surge un popularity. It became so popular that the government set up regulations prescribing when and where the dance could be performed. One official told the Washington Post, "I don't think the old folks are paying too much attention. They're pretty much doing whatever they please.” The popularity of the dance is attributed to a desire to have fun, nostalgia and desire for good health among the elderly. Many of those who do it say the dance has helped them lose weight and cure their back problems. One woman in her 50s who performs the dance every morning in Ritan Park in Beijing told the Los Angeles Times, “If you are happy, you won’t get sick. Dancing gives me energy.”

Square Dance in China

Square dancing in China refers to dances done in a public square rather than American-style square dancing. Describing some of these dances performed at the Galaxy Awards competition for community art held in Qingdao, Shandong province in 2013, Sun Ye wrote in the China Daily: “With a rattlesnake whip in one hand, use the other to give yourself a tap on the shoulder, then your elbow, wrist, waist, kneecap and instep until you have tapped each joint in your body. It looks like the perfect stretching exercise. Except you are holding a whip decorated with six little coins that give a jaunty jingle with each "swish". It's no surprise this dance has become a popular daily sight at People's Park in Dali, Yunnan province.[Source: Sun Ye, China Daily, November 13, 2013]

The routine is not solely for exercise. The rattlesnake dance, a signature dance of the Bai ethnic group in the area, is an emotional expression of culture. "Listen to the coins, it's how we welcome wealth and happiness. It's our tradition to dance the rattlesnake dance at major festivals and celebrations," explains Yang Zhenyi, 36, who led her group of amateur dancers from Yunnan "The dance at the square we practice daily is easier than the original ones, but it's the same free-spirited and engaging dance that just makes you happier and happier when you tap to the tune," says Yang. "I've only seen the full set of dances in the village where my grandparents lived, but I love it." Yang was raised in the city and is a clerk at the local art museum. Dancing in the square is best accompanied by impromptu Bai ethnic tunes sung a cappella. "Listen to it, we dance to say how lovely we Yunnan 'golden flower' girls are," Yang says.

“Just like the whip dance, the Kazakh traditional dance Karajurha tells the story of how men ride horses and wrestle and how women sew and children play. This traditional dance has also evolved into an engaging square dance and a morning exercise at schools. "We're used to dancing it whenever there is a wedding or happy get- together," says Ersen Heyzat, from the Altay prefecture of the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region. He led his group of dance enthusiasts to the Galaxy Awards. He has also designed a set of school exercises based on Karajurha. "When the tribe still lived on the grassland, it was danced while on a horse. Therefore it's the same tempo as the horses prance," he says. "It's easy as long as you know how to shrug, as most moves are in the upper body," says Heyzat. "For the Karajurha square dance, there is nothing you can't learn in a minute and no standard you can't match." "That's the point of square dancing. It's easy." In Usu in Xinjiang, young and old participate in ethnic square dancing every evening in the summer in several plazas around the city. "We don't wear an owl's feather or ultra-long sleeves (the traditional dance clothes) for daily square dancing," Heyzat says. "But the movements still reflect our moods, that we are very happy with our lives."

Fan dance of lower Yangtze

“Square dancing can be witnessed across the country in the morning and early evening in warm weather, but it is not always welcome. “China News Service reported in August that a group of Chinese immigrants in New York were dancing in public with a stereo that was so loud that it attracted the attention of police. Beijing Youth Daily reported a case in Shandong province where a man fired a gun and unleashed his dogs to dispel a dance group who danced late into the night in early November.

“But square dances, especially those with strong cultural ties, are worthy of public appreciation. "It dates back to the traditional folk dances, it's a natural invention," says Ming Wenjun, vice-president of Beijing Dance Academy. Ming is a specialist in folk dance research and was on the judging panel of the Galaxy Awards. "They start as a ceremony related to the group's belief, cultural lore, and are part of educating the group on manners and behavior," Ming says. "These functions of the dances weaken with urbanization, but the dances remain a very important part of our culture."

“Square dancing cannot be properly categorized because it is a mixture of styles and themes. It's engaging, entertaining and distinctly characteristic of one's cultural upbringing." In the Galaxy Awards “the square dances are representative of a group's cultural identity," Ming says. "You see a soft whip, or a longevity drum, or an umbrella prop, you immediately know the dancer's hometown." "The square dance is fun and easy for the dancers themselves. People become very invested in it," Ming says. “And most importantly, the dance brings the dancers knowledge of themselves. "The moves are the ritual that gives us Chinese the sense of order and human relations," Ming says. "Questions of who we are, and why we Chinese cling to our home, are answered here."

Dragon Dance, Lion Dance and Festival Dances in China

The dragon dance and lion dance are performed during Chinese New Year and the Lantern Festival. The boat dance and donkey dance are performed during Chinese New Year and the Lantern Festival. Boat dancers are women or men disguised as women who wear a boat-shaped prop around their waist that covers their legs with pieces of silk. While singing the dancers imitate boat movements while a boat man follows them. The trotting donkey dance is similar to the boat dance but the story and props are different. The women in this dance wear a donkey prop around their waist and pretend they are carrying a child in their arms. A man follows behind the "donkey" with a whip. The "donkey" sometimes goes fast, sometimes slow and sometimes falls in a pit while the man works up a big sweat wrestling and struggling with the animal.

The dragon dance is one of the most well known Han Chinese dances. By one count there are 700 versions performed throughout China, with specific regions often having their own version. The dragon is an important totemic creature to the Han Chinese. According to legend, the great hero Fu Xi and his sister Nu Wa descended from semi-human creatures with snake bodies. Over time these creatures were given animal legs, a horse mane, a rat tail, deer hooves, dog claws and fish scales and they became the dragon were are familiar with today.

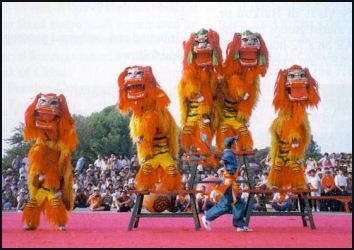

Lion dance

Dragon dances feature huge dragons made of colored paper, cloth, and small battery-lit lanterns shaped like fishes and shrimp strung together with pieces of cloth. To the deafening sounds of gongs and drums the "dragon" dances up and down the streets while strings of firecrackers and fireworks are set off. There are special moves. It is important for dances to be well coordinated. There are professional dragon dancers and dragon dancing competitions.

According to legend the dragon dance was created to honor a doctor who picked a centipede from a dragon's back. The waving movements of the dance show appreciation by the dragon, who controls natural forces that bring about a good harvest. According to the Guinness Book of Records, the world's longest dancing dragon was 5,550 feet from nose to tail. It was made up of 610 people in May 1995.

In the lion dance, two dancers wear a lion costume which works a bit like the horse costumes used in old vaudeville routines. One dancer is the head and forelegs. The other dancer is the tail and hind legs. Together as the "lion" they performs feats like the "playing with water trick" and the "climbing the shed trick."

The lion dance honors a lion who was ordered by the Jade Emperor to remove evil spirits from the world and was later invited to stay in the world to keep them from coming back. The dance often begins with the placing of a drop of chicken blood on the lion mask.

Ballet and Modern Dance in China

The Chinese love ballet. Western classical ballets are performed in the biggest metropolises. Chinese have a special fondness for Swan Lake.It was the first full-length ballet performed after the founding of the People Republic of China (See Swan Lake Acrobatics, Entertainment). A ballet version of Raising the Red Lantern has drawn some attention. Margot Fonteyn started her long dance career in Shanghai, in 1933. A number of Russian dancers taught in China and had great influence there until the 1960s when relations between China and the Soviet Union began falling apart.

Modern dance dramas are created combining Western and Chinese dance techniques. One very influential work in this field has been the Tales of the Silk Road, Silu huayu (Szû-lu hua-yü), which had its premiere by the Gansu Provincial Song and Dance Ensemble in 1976.

Yang ge dancers at a festival

The dance drama is set in Central Asia during the Tang period, in the region of the Silk Road connecting China with Persia and the Mediterranean region. Full use was made of the famous Dunhuang Buddhist cave murals, which are located in Gansu province. By studying the paintings and combining their poses with the Russian ballet technique and Chinese acrobatics, the choreographers created a kind of historical fantasy style which had had a great appeal for audiences, both in China and abroad. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

The semi-historical, fairytale-like glamour aesthetics captured in the Silk Road ballet is regularly employed by grand tourist spectacles, the most prominent of them being the Tang Dynasty Dances performed in Xian, formerly Changan, the old capital of the Tang Dynasty. With its sugar-sweet visualisation and play-back musicians and singers it has served as a model for similar kinds of tourist entertainment throughout the country. **

Chinese have done very well in international ballet competitions. Chinese classical dance and ballet have many similarities and Chinese dance training is in tune with the training required of ballet dancers. Beryl Grey, a British ballerina who was recruited to whip the Beijing Ballet into shape in the 1960s wrote: “I had not expected to see such good limbs and well arched feet. Their backs were unusually supple and their extensions high without any apparent forcing. The oriental fluidity of their arm movements was particularly suited for Swan Lake as were their long slender necks. But I was perhaps most impressed by the dignity and poise, the quiet composure and concentration with which they tackled everything.”

Shen Wei is a highly acclaimed choreographer. Trained in Chinese opera, he was a found member if China's first modern dancer company and now works mostly out New York. Some pieces have featured near nude dances. Other were inspired by the painter Francis Bacon.

Huang Dou Dou is an internationally-known dancer and choreographer. Born in 1977 and based in Shanghai, he is known for creating elegant dances that combine martial-art-like movements with Peking Opera gestures.

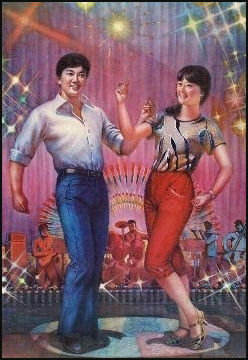

Discos and Ballroom Dancing in China

In the 1990s ballroom dancing was very big. Dozens of couples gather at dawn before work in Shanghai's Peace Park and other parks in China to practice their mambo, tango and cha, cha, cha steps. Most of the dancers were under the age of 25. The activity remains popular. There are over 100 ballroom dance halls in Shanghai. "People say they go to ballroom dancing for their health," American scholar James Farrer told Newsweek. "But it always married people without their spouses."

Ballroom dancing is being offered in schools as a way of combating the rise in obesity among young people. An official in the state sports administration was quoted in Time, saying, ‘students will be grouped together to perform the waltz, and they will change partners regularly...This way the risk of young love will be lowered.”

Discos are becoming increasingly popular in China. Men and women usually don't dance as couples. Friends usually dance in a group. Women often dance together and men sometimes dance with each other. Often you are more likely to see people of the same sex dancing together than people of the opposite sex. Sometimes men even slow dance together.

Image Sources: 1,5) Atlanta Chinese Dance Company; 2) McClung Museum; 3, 7) Princeton University; 4) Wushu Academy; 6) University of Washington; 8) Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html; 9) CNTO; 10) Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021