REVOLUTIONARY OPERA IN CHINA

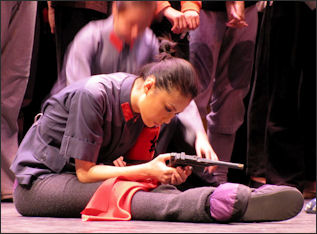

Tiger Mountain Revolutionary Opera Revolutionary Opera — also called model opera — created by Communists, reaching their peak in the Cultural Revolution, gloried farmers, workers and soldiers rather heros from the feudal aristocracy. The plots revolved around class struggle and revolution and had titles like such as “Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy”.

The popular play that many scholars say triggered the entire Cultural Revolution was “The Dismissal of Hai Rui from Office”, a drama by historian Wu Han about an obscure Song dynasty official. The play was widely seen as as a traitorous critique of Mao's dismissal of Peng Dehuai, a military leader who criticized the Great Leap Forward.

Mao’s wife Jiang Qing was put in charge of the arts during the Cultural Revolution. She and her group of loyalist intellectuals and artists controlled everything: film studios, operas, theatrical companies and radio stations. Jiang reviewed more than 1,000 operas and concluded that nearly all of them were unacceptable because they dealt with "emperors, officials, scholars and concubines." She commissioned a series of "revolutionary modern model operas” with heroic figured that displayed socialist virtues. These operas were based on Peking opera but featured Western devises that were deemed appropriate for furthering revolutionary goals.

Jiang Qing decided that eight operas were the only permitted forms of art in China, and they are heavily associated with the ideologically-charged violence of the period. Among the eight operas authorized by Jiang were “The Girl with White Hair” (about a woman who loses her natural coloring because of an evil landowner), “Red Women's Detachment”, and “Songs of the Long March”.

The operas were adapted for symphony orchestras, dance troupes, piano music and even ethnic minority songs. In the 1960s, Chinese teenagers listened to songs form these operas while Americans were listening to the Beatles and the Supremes. Alex Ross wrote in The New Yorker, “Red Detachment of Women” has “a kitschily charming score in a light-classical vein, with an array of native-Chinese sounds.”

Under the Communists the practice of using either all-male or all-female cast was abolished. Even today national troupes "perform paeans to brave soldiers who saved the country from floods." The music also remains alive. Red Rock and Roll is a collection of Cultural revolution songs covered by modern musicians.

See Separate Article MUSIC, OPERA, THEATER AND DANCE factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE OPERA-THEATER AND ITS HISTORY factsanddetails.com; TYPES OF CHINESE THEATER AND REGIONAL OPERA factsanddetails.com; CHINESE AND PEKING OPERA STORIES, PLAYS AND CHARACTERS factsanddetails.com; PEKING OPERA AND ITS HISTORY, MUSIC AND COSTUMES factsanddetails.com PEKING OPERA ACTORS factsanddetails.com; MODERN AND WESTERN THEATER IN CHINAfactsanddetails.com CHINESE DANCE factsanddetails.com ;

Websites and Sources: Chinese Opera Wikipedia article on Chinese Opera Wikipedia ; Beijing Opera Masks PaulNoll.com ;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Mao's Cultural Army: Drama Troupes in China's Rural Revolution” by Brian James DeMare Amazon.com; “Staging Revolution: Artistry and Aesthetics in Model Beijing Opera during the Cultural Revolution” by “Xing Fan Amazon.com; Revolutionary Bodies: Chinese Dance and the Socialist Legacy” by “Emily Wilcox Amazon.com; “A Continuous Revolution: Making Sense of Cultural Revolution Culture” by Barbara Mittler Amazon.com; “Maoist Model Theatre: The Semiotics of Gender and Sexuality in the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976)” by Rosemary A. Roberts Amazon.com; “Red Detachment of Woman: a Modern Revolutionary Dance Drama” Amazon.com “Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy;: A Modern Revolutionary Peking Opera” Amazon.com; “Acting the Right Part: Political Theater and Popular Drama in Contemporary China” by Chen Xiaomei Amazon.com; “Chinese Theater: From Its Origins to the Present Day” by Colin Mackerras Amazon.com; “Chinese Opera: Stories and Images” by Peter Lovrick and Siu Wang-Ngai Amazon.com; “Peking Opera” by Chengbei Xu Amazon.com; “Chinese Opera: The Actor’s Craft” by Siu Wang-Ngai and Peter Lovrick Amazon.com; “Drama Kings: Players and Publics in the Re-creation of Peking Opera, 1870-1937" by Joshua Goldstein Amazon.com; “Listening to Theater: The Aural Dimension of Beijing Opera” by Elizabeth Wichmann Amazon.com;

Theater and the Early Communist Party

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: Leftist ideologies were common among intellectuals in the 1920s and 1930s. Even from its rise in the early 1920s the Communist Party of China realised the value of theater as a weapon for social change. Mao Zedong (Mao Tse-tung) set the guidelines for the Communist theater and proclaimed complete party control over the arts, a policy which reached its nightmarish culmination during the Cultural Revolution in 1966–1976. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

Folk arts were revised to propagate revolutionary ideas. Some of their traditional features were maintained but much was modernised. Traditional opera styles, such as Peking Opera as well the clapper opera and other regional forms, were used as a basis for new dramas on contemporary themes and often aimed as propaganda against the Japanese. **

New Peking operas were created. An acclaimed example is Forced Up Mountain Liang, Bishang Liangshan (Pi-shang Liang-shan), which was based on a historical epic, Outlaws of the Marsh, Shuihu zhuan (Shui-hu chuan). Although it portrayed events in the distant past, it acutely propagated rebellion against the feudal system. It had its premiere in 1945. **

In the same year a new geju or song drama, The White-Haired Girl, Baimao nü (Pai-mao nü) was performed for the first time. Its music was based on traditional folk melodies and it was accompanied by an orchestra which combined Chinese and Western instruments, while its costuming and décor aimed at realism. It was a great success and it was later revised and finally transformed into a revolutionary model ballet. **

Returning Home on a Snowy Night

new Red Detachment of Women Raymond Zhou wrote in the China Daily, “It must have looked like an escape from reality when Wu Zuguang wrote and first presented "Returning Home on a Snowy Night" in 1942. Fires of war were engulfing China, yet not a hint of either the Japanese invasion or Chinese resistance could be detected in the play. This was in the wartime city of Chongqing, where many of the nation's glitterati had found refuge, in contrast to Japanese-occupied Shanghai, where Chinese filmmakers injected innocuous entertainment with somber overtones and subtle allusions to the woes of foreign occupation. [Source: Raymond Zhou, China Daily, December 12, 2012 +]

“However, the story of a Peking Opera star in love with the concubine of an official not only survived, but has turned into a classic with increasing relevance. The craze for pop sensation and the hypocrisy of officialdom have never been truer today even though the romance at the heart of the story is so starry-eyed it borders on unbelievable. Well, it serves well as an antidote of eerie idealism at least. +\

“In contrast with these leading performances, two supporting roles provide comic relief as well as the uglier side of humanity. The butler who latches onto the next powerful person and sells out those who have helped him seem like a reincarnation of Monsieur Thenardier from Les Miserables, born into a Beijing household. The student who gives up everything to hover around the star, ingratiating himself into his circle and believing himself to be an indispensable part of the star ecosystem, is the predecessor of the modern lunatic whose dream is becoming a groupie. There are no sexual innuendos but he is dumb but hilarious. +\

On a 2012 production of "Returning Home on a Snowy Night" at by the National Center for the Performing Arts, Zhou wrote:: The production stands out for its stellar cast, among other things. Feng Yuanzheng, a pillar of versatility and subtlety on the Chinese stage, plays the official, or chief justice, to be specific, who has the sophisticated taste of an opera patron and the ambiguous sexuality of having four wives while chasing a female impersonator. Feng does not go the cheap way of caricature, but imbues the character with complexity. The last scene in which he, as a newly devout Buddhist, sends his butler to bury the homeless person found frozen to death in his ornate yard, without realizing it was the star he once adored and then expelled from the city, has true pathos. The hypocrisy, if it can be so called, is ingrained so deeply in our psyche that it is nothing like that seen in a typical melodrama. [Source: Raymond Zhou, China Daily, December 12, 2012]

“The big surprise is Yu Shaoqun, who plays the 25-year-old opera star who grows up in a humble family and still retains his innocence and sense of justice. Yu, who gained fame by playing the young Mei Lanfang in Chen Kaige's 2009 biopic Forever Enthralled, looks stunning in full Peking Opera regalia. With opera training from a young age, though not Peking Opera and not in female roles, he pulls off the opening scene of the character on stage with strong credibility. The fantasy scene that closes the play, where he does a dance with the older self's corpse in the foreground, again in female garb, elevates the tale of love to a higher plane. +\

Theater and Dance in the Early Maoist Period

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: The early phase of the People’s Republic, starting from its establishment in 1949, was an active time for the arts, as they were employed in the construction of the new society. The social status of theater workers greatly improved, as they had their undeniable role in the class struggle and were no longer regarded merely as prostitutes. The policies that Mao Zedong had formulated earlier became the guidelines for all the arts, and also for the theater, which was particularly appreciated for its educative value. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

new Red Detachment of Women Regional theater forms were reformed, and modern forms, such as huaju or spoken drama and geju or song drama were encouraged, of course, but only if they followed the strict official guidelines. A completely new form of art was created, the full-scale wuju or dance drama, which clearly reflected the close cultural ties between the People’s Republic and the Soviet Union. Committees were set up and festivals held in order to define the exact role of theater and dance in the new society. In 1950 the Ministry of Culture established the Traditional Music Drama Committee to plan a drama reform. It was agreed that even the traditional forms of theater should be reformed so that they promoted patriotism and served Communist ideology and revolutionary heroism. **

In the same year the First Nationwide Spoken Drama Festival made the Soviet influence apparent. Many productions reflected the psycho-realistic acting style, while realistic costumes and sets became the norm. Spoken drama was regarded as a suitable medium with which to portray modern life with its continuous class struggle. In 1952 the First National Music Drama Festival gathered together some 1800 performers from all over the country. **

In his speech in 1956 Mao Zedong launched the famous slogan: “Let a hundred flowers blossom, and a hundred schools of thought contend.” The following so-called “Hundred Flowers Period” was a rather liberal time. In the same year that Mao delivered his speech, the Kun Opera was revived in the famous production of Fifteen Strings of Cash attended by Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai. Next year Lao She’s spoken drama Teahouse, already discussed above, had its premiere. Many music dramas and other spoken dramas were also created. **

The year 1957 also saw the premiere of the first Chinese large-scale dance drama, The Precious Lotus Lamp. It reflects many Western, mainly Soviet, influences. In movement vocabulary the ballet aesthetics were combined with national elements and flavour and pas de deux duos between the male and female leads were created in a similar way as in the Western ballet which was now also being taught in China. Prior to 1963 the official policy was to combine the modern and the traditional and to rewrite traditional works to reflect patriotism and Marxist ideology. Political censorship grew stricter, however, and after 1963 attitudes rapidly changed. Due to the power game manipulated by Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing (Chiang Ch’ing), herself a former actress, all traditional forms of theater were gradually banned. The new guidelines for theater were announced at a festival of modern opera in Peking in 1964. Thereafter, only operas with modern themes were favoured. **

Evolution of Revolutionary Opera

In a book review, Xiaomei Chen wrote: “”Xing Fan’s Staging Revolution” focuses on the complexities of the “revolutionary modern Peking opera” promoted during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), also widely known as “model theatre”, an art form hich “succeeded in expressing the gist of modern revolutionary life through appropriating traditional acting styles despite the “incompatibility between the content of modern stories and the form of traditional jingju” A good example of the evolutionary process can be seen in the “The White-Haired Girl”, which has usually been traced from Yan’an folk opera, to the early 1950s film, to the spoken drama, to the Western ballet versions of the 1960s, and finally to the crowning success of the model ballet during the Cultural Revolution as well as its postsocialist reincarnation as a “red classic.” [Source: Xiaomei Chen, University of California, Davis, MCLC Resource Center Publication, June, 2020; Book:“Staging Revolution: Artistry and Aesthetics in Model Beijing Opera during the Cultural Revolution” by “Xing Fan (Hong Kong University Press, 2018)]

Rather than destroying traditional acting conventions, model jingju (Peking Opera) in fact borrowed “performance techniques from multiple particular role-subcategories and then fused them into the presentation of a character’s inner world, personality and individuality” Fan eloquently demonstrates how the political choices of theatre reform, as seen in model theatre, were “realized through the most rigorously formulated artistic choices and carried out by exceptional performances and entertaining techniques and devices” Dramatic characters in a radical revolutionary era were “brought to life onstage, thus revealing the special features of stage production” and “the artistic components of model jingju”

Debunking the familiar narrative, traditional operatic performances were in fact more popular and more frequently staged in Yan’an — where the Chinese Communist Party was based before it took over China in 1949 — than revolutionary new operas. The period from 1948 to 1956 is characterized as a time when the People’s Republic of China (PRC) tried to reform operatic theatre (xiqu) and experimented with themes and plots, Fan highlights the reform’s failure to meet the demands of opera’s prolific traditions and their ongoing impact on artistry and practice, thereby paradoxically acknowledging the “old theatre’s power, based on its popularity” (29). The xiqu reform caused confusion in its implementation and was also sometimes unable to account for the performance-centered nature of the art.

The mid-1950s experimental production of Three Mountains — originally a Mongolian opera based on a folksong but later adapted as jingju — revealed its producers could not fully integrate traditional Chinese and Western musical instruments into a coherent and overall style of jingju music. Mao’s confirmation of the value of artistic reform and Jiang Qing’s indifference to it foreshadowed the important role jingju was yet to play a decade later during the Cultural Revolution.

from 1956 to 1965, Fan demonstrates how the rising socialist zeal for creating new art followed a path that zigzagged between frustration with the negation of traditional opera arts and frantic re-orientation according to the changing political winds; theatre artists, critics, and cultural bureaucrats adopted various strategies of survival and preservation while creating the best “socialist arts” possible under the circumstances. Her account of the success of the jingju version of The White-Haired Girl not only illustrates the laborious but ingenious efforts to modernize a traditional art form. Describing model jingju as a gradual reform of rather than an abrupt break from tradition, Fan argues that model jingju design “developed elaborate scenery specifically created for each production, and the scenery indicates an overall close-to-realistic style” achieved by collective teams consisting of a chief scene designer and several subordinate designers.

Theater During the Cultural Revolution

Culture in the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) was spearheaded by the infamous Gang of Four, including Mao’s wife Jiang Qing. All traditional forms of theater were prohibited. Model operas deemed politically acceptable pieces were introduced into the oeuvre by Jiang Qing.The Cultural Revolution was a time when anything traditional was under attack and Peking Opera was no exception. Given the subject matter of classical operas, which told stories of emperors, concubines and generals, they were deemed as remnants of a feudal past which had no place in the new communist China. The majority of opera theaters were thus closed, and many famous stars vilified, some even driven to suicide. The performance of traditional pieces was banned and the new model operas introduced in their stead focused exclusively on revolutionary stories exemplifying communist tenets. [Source: Pallavi Aiyar, Asia Times, July 19, 2008]

old Red Detachment of Women Wang Rukun, a senior teacher at the Peking Opera Vocational College, recalls how his training as a young boy at the same school was cut short by the Cultural Revolution. It took nine years to complete a full training regime at the time. Classes took up to 10 to 12 hours a day and all the students boarded in, separated from their parents. Their sole focus was on their art. But after Wang spent only seven years in the school, the Cultural Revolution broke out and all regular opera performances were canceled. His own study of classical works came to an abrupt halt and he began instead to learn the eight model operas authorized by Jiang Qing, spending the next decade performing in the countryside and at factories for audiences of workers and farmers.

Besides the actual model works, huge spectacles combining different forms of the performing arts were also set up. The East is Red, Dongfang hong (Tung-fang hung) was an example of this kind of “revolutionary entertainment” which aimed to illustrate the success story of the revolution. Besides these model works and spectacles very few other works were allowed to be performed. Actors, writers and other theater workers who refused to join the teams, or were otherwise regarded as anti-revolutionaries, were persecuted and many of them died. However, many well-known actors played in the model dramas and their artistic level was the highest during the Cultural Revolution. No wonder that the model dramas are still rather popular today. Together with the model ballets, they are still performed every now and then. They are all available as recordings and even revolutionary opera karaoke was in vogue at the turn of the 21st century. **

Model Operas During the Cultural Revolution

Jian Qing had inspected some 1000 Peking operas and suggested banning most of them. The Communist Party’s literature committees dictated what was allowed to be performed. The eight approved model opera in the Cultural Revolution were not created from scratch during the period but evolved from their original versions as huaju, novel, film, or dance drama (wuju) and were already popular and successful pieces, providing solid groundwork for the model opera adaptations. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

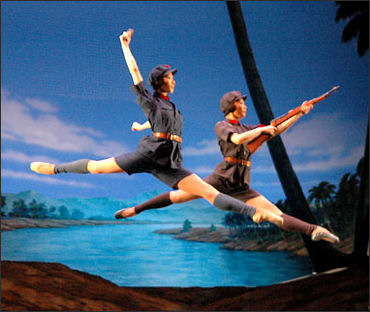

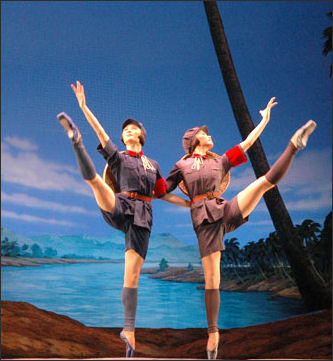

Miettinen wrote: The first model drama was ready to be performed in 1969. The model works came to include eight works altogether, regularly revived by the party committees to reflect the current trends of the party’s policy. They include the above-mentioned five model dramas, one symphony (Yellow River) and two Model Ballets, The Red Detachment of Women, Hongse niangzi jun (Hung-sê niang-tsu( chün) and The White-Haired Girl, which was reformed from an early song drama into a model ballet. Revolutionary ballets make full use of Soviet-style heroic classical ballet with pointe shoes and furious leaps. **

In the huge stage decors, costuming, and in make-up, “heroic realism”, were the only accepted style. The music is a mixture of traditional Chinese and Western music since, according to Jiang Qing, Western music was more suitable to express heroism than Chinese music. Many stage conventions, as well as acrobatics, were retained from the traditional Peking Opera, although in the fighting scenes guns and rifles now replaced the traditional weapons. **

One of the main features of Chinese communist red operas is the incitement to hatred, according to Xing Lu, a scholar of communications at DePaul University who has written a book about rhetoric in the Cultural Revolution. “Hatred permeates every model opera,” she writes. According to her book, the basic message behind these pieces is that those designated as “class enemies,” or “villains,” must be eliminated through violent struggle, so a new society can be established. The plays were meant to foster a “deep hatred for all class enemies and love for the Communist Party,” Lu writes. [Source: Matthew Robertson, The Epoch Times, February 11, 2013]

As for music Barbara Mittler argues that model jingju music “actually perpetuated” the so-called bourgeois individualist music that was a target of the Cultural Revolution and took its “rightful place in a long series of attempted syntheses of foreign and Chinese heritage” in the four areas of orchestra organization , percussive music , instrumental music and vocal-melodic music , for instance, the innovations of both traditional jingju orchestration and Western-style orchestration “demonstrate significant, new dimensions of musical composition”. Conductors of both the jingju orchestra and the general conductor for all orchestras had to develop new skills in accommodating a combined team for its full artistic potential, thus making orchestra conducting a fascinating area for experimentation. [Source: Xiaomei Chen, University of California, Davis, MCLC Resource Center Publication, June, 2020; Book:“Staging Revolution: Artistry and Aesthetics in Model Beijing Opera during the Cultural Revolution” by “Xing Fan (Hong Kong University Press, 2018)]

Jiang Qing and the Creation of Cultural Revolution Operas

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: Jiang Qing interpreted Mao’s teachings extremely rigidly, which led to the politisation of theater to an extent that has never been seen, before or after, in the history of the arts. Five Revolutionary Model Dramas were created by the literary circles led by Jiang Qing. They included Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy, Zhiqu wei Hushan (Chih-ch’ü wei Hu-shan), The Red Lantern Hongdeng ji (Hung-teng chi), Sha Jia Creek Shajia bang, (Sha-chia pang), On the Docks Haigang, (Hai-kang) and Raid on the White Tiger Regiment Qixi Baihu tuan, (Ch’i-hsi Pai-hu t’uan). [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

Jiang Qing formulated new theatrical aesthetics for these model operas. Similarly, as the earlier traditional operas, the model operas were also based on fixed character types. However, the various earlier types, based on their social status and inner qualities, were now replaced with character types based solely on their class background.These rigid stereotypes include two main categories. The revolutionary and thus “good” characters are portrayed as standing in the middle of the stage in heroic, “revolutionary” poses, well lit with pinkish spotlights (red being a positive colour both in the traditional and later in the Communist colour symbolism). The “bad” characters, i.e. the class enemies, are placed at the side of the stage in ugly poses and dimly lit by bluish light (blue often being a negative colour in traditional opera masks). **

In a review of the book, “Staging Revolution” Xiaomei Chen wrote: The belief that the “three prominences” was mostly an invention of Jiang Qing and her associates in creating model theatre” is not totally correct. “It can in fact be traced to Jin Shengtan , whose analysis of Wang Shifu’s Romance of the Western Chamber pointed to “negative characters to set off other regular characters, using other regular characters to enhance major characters, and using major characters to accentuate the central characters,” as Fan describes it. While noting that Jin did not categorize characters into negative and positive, Fan demonstrates how in the process of revising Taking “Tiger Mountain by Strategy”, the theory of the “three prominences” resulted in an increasingly strong focus on Yang Zirong , the principle hero, while gradually reducing the original panoply of colorful negative characters to Vulture and his gang. [Source: Xiaomei Chen, University of California, Davis, MCLC Resource Center Publication, June, 2020; Book:“Staging Revolution: Artistry and Aesthetics in Model Beijing Opera during the Cultural Revolution” by “Xing Fan (Hong Kong University Press, 2018)]

Her table of comparisons of the plot between five different revisions of “Tiger Mountain by Strategy”, from 1958 (borrowing in part from the Beijing People’s Art Theatre’s spoken drama [huaju] production) to the final 1970 model jingju version, supports her argument that not only was the formation of the model jingju a result of a long process of artistic re-creation prior to the PRC period with certain roots in classical drama, but it also “encompasses a search for both revolutionary political content and the highest artistic form possible”.

Jiang Qing’s emphasis on the importance of script writing and revisions and her requirement that “jingju’s characteristics be applied in lyrics, music, movement, and artistic language” provides a more balanced picture of the creation of model theatre as a cultural art form with enduring appeal in contemporary times. Fan gives Jiang Qing due credit as the general director/administrator controlling and contributing to all artistic aspects of model jingju revision; Fan renews attention to Jiang’s role as a theatre artist against the usual depictions of her as a political manipulator and villainous woman who destroyed the jingju tradition. Fan’s account of Jiang’s directive to use conventions while avoiding conventionalization and her exploration of how actors, musicians, script writers, and designers carried it out in the revision process illustrate the importance of a comprehensive study of this artistic practice.

new Red Detachment of Women

Red Detachment of Women

“The Red Detachment of Women” is a 1964 Chinese ballet that glorified violent class struggle before the Communists came to power. One of just eight Party-approved model operas performed during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), it revolves around the heroic defeat and execution of an “evil landlord” by communist partisans in the 1930s. The ballet was derived from the 1961 Chinese film “The Red Detachment of Women” by Xie Jin, produced under the personal direction of Zhou Enlai, on a script by Liang Xin. Performed for U.S. President Richard Nixon on his visit to China in February 1972, the ballet is still performed today the state-run National Ballet of China and was staged at New York’s Lincoln Center in 2015.

The novel by Liang Xin depicts the liberation of a peasant girl in Hainan Island and her rise in the Chinese Communist Party. The novel was based on the true stories of the all-female Special Company of the 2nd Independent Division of Chinese Red Army, first formed in May 1931. The group had over a hundred members. As the communist base in Hainan was destroyed by the nationalists, most of the members of the female detachment survived, partially because they were women and easier to hide among the local populace who were sympathetic to their cause. After the communist victory in China in 1949, the representatives of the surviving members visited to Beijing and were personally praised by Mao Zedong. In 2014, Lu Yexiang, the last member of red detachment of women, died in Qionghai, Hainan. [Source: Wikipedia]

The main characters are 1) Qionghua, the heroic woman fighter: 2) Hong Changqing, the Communist Party representative, and Nan Batian, the evil landlord. Hong Changqing, disguised as an oversea businessman, frees Qionghua, who had been tortured, from Nan Batian. Qionghua states her intention to be a soldier to fight against the feudal landlord. Guiding by Hong Changqing, Qionghua makes her way to the encampment with another young woman, Fu Honglian, who refuses her life as a widow. They are welcomed by the Red Detachment of Women because of their poor backgrounds.

During a reconnaissance mission, Qionghua encounters Nan Batian and fires at him. Batian is wounded but Qionghua's mission is considered a failure. Later, Hong Changqing and Wu Qionghua, disguised as a businessman and his maidservant, enter Nan Batian's fort as spies. In a a battle of Batian's fort, the Red Army successfully occupies the fort with help from Hong Changqing and Wu Qionghua inside and capture Nan Batian alive. However, the crafty Nan Batian escapes through a tunnel. In the following peasant movements, Qionghua takes an active part and she applies to join the Chinese Communist Party.

After making his escape, Nan Batian reports the situation to the government and the Kuomintang assigns a brigade to attack the Red Army in Hainan Island. The Red Army retreats to the mountains. In a battle to cover the retreat, Hong Changqing is wounded and he is captured alive. He refuses to betray his comrades and face his death bravely. Qionghua witnesses Hong’s death, returns to the encampment and becomes the Party representative. She organizes an operation to destroy Nan Batian's forces after the KMT brigade leaves Hainan Island. They successfully occupy Batian's fort again and sentence Nan Batian to the death. Under Qionghua's leadership, the Red Detachment of Women marching onward to a bright future.

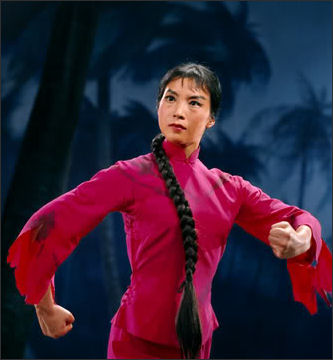

White Haired Girl

“White-Haired Girl” is a famous play and Cultural Revolution revolutionary ballet. Chris Buckley wrote in the New York Times’s Sinosphere: Mao Zedong was said to have been moved to tears when he watched an early performance of “The White-Haired Girl,” an opera created to meet his call for rousing revolutionary art. The opera was first performed in 1945 in Yan’an, the Communists’ revolutionary base in northwestern China, inspired by Mao’sprecepts for revolutionary art and literature delivered at a landmark forum in 1942. [Source: Chris Buckley, Sinosphere, New York Times, November 10, 2015]

““The White-Haired Girl” was also adapted as a ballet during the Cultural Revolution. Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing, a trained actress, sang parts of the opera and, after she amassed power during the Cultural Revolution, oversaw a ballet adaptation as part of the repertoire of revolutionary “model” stage works.

“The White-Haired Girl” is a dramatic story that has endured the shifts in China’s political winds over the decades. Each period since its first performance has brought adaptations, including a well-known film version in 1950 and the later ballets. The swelling, lyrical music absorbs traditional songs and opera from northern China. “The music is so familiar to anyone over, say, 40 or 50,” Paul Clark, a professor at the University of Auckland in New Zealand who has studied Chinese film and culture from the Mao era, Clark said. “The vividness of the imagery of her hair turning white and so on is quite something for Chinese, in particular, who are used to monochromatic hair.”

“Mao arrived late the first time he went to watch the opera, Brian James DeMare, an assistant professor of Chinese history at Tulane University and author of “Mao’s Cultural Army: Drama Troupes in China’s Rural Revolution,” told the New York Times. “Mao was not personally involved in the creation of the show, but must have approved of the show,” he said. “Party leaders did send the creators a note asking for the landlord to be executed at the end.”

White-Haired Girl Story

old Red Detachment of Women Chris Buckley wrote in the New York Times’s Sinosphere: “The story centers on Xi’er, a young peasant woman in a north Chinese village, whose family is persecuted by a brutal landlord who drags her away to serve as his slave and concubine. She eventually escapes to the hills, and for years, she finds shelter in a cave, where her hair turns white, giving rise to the local belief that she is a ghost. Her fiancé, Wang Dachun, who has joined the Communist forces, returns and decides to look for her. He finds her in her cave, and they rejoice in a future together under revolutionary liberation. [Source: Chris Buckley, Sinosphere, New York Times, November 10, 2015]

“In the original version, the heroine becomes pregnant after being raped by the villainous landlord,” DeMare said, “After she realizes she is pregnant, she initially hopes to marry her attacker, but ultimately runs away when she realizes that she is to be sold off.” Later versions were bowdlerized to omit her pregnancy. “By the Cultural Revolution, when a ballet version of the show became a model work, the portrayal of the characters was totally revised,” Mr. DeMare said. “Now the landlord could barely menace the strong peasant characters, robbing the show of the original’s emotional charge.”

The White Haired Girl is based on the legend of a white-haired female immortal. It tells of Yang Bailao, a tenant farmer who shares his life with his daughter Xi’er. The despotic landlord, Huang Shiren, attempts to forcibly take Xi’er for himself. On the eve of the Chinese Spring Festival, Huang forces Yang to sell his daughter as repayment of the debt Yang owes him. Yang drinks bittern and dies. Xi’er is taken by force to Huang’s house and raped by the landlord. [Source: EastSouthWestNorth]

The girl is in love with Dachun, a young farmer in her village, who tries to help her escape but fails. He goes to find the Red Army. Xi’er runs away from Huang’s house and hides herself deep in the mountains. She leads a miserable life, and her hair turns completely white. Two years later, Dachun returns to the village with the army unit he is in. He finds Xi’er and helps her get even with the hated landlord. They marry and lead a happy life after emancipation.

Today there are those that think the White Haired Girl should marry the evil landlord Huang Shiren as sympathy that used to exist for poor and oppressed people in the 1940's has been replaced by blind adoration of money. A student at Central China Normal University said, “If Huang Shiren were alive today, he is definitely somebody with excellent family conditions. He may also have handsome looks combined with elegance and refined taste. If he has money as well, why not marry him? Even if he is a bit older, it does not matter.

One Netizen wrote: “I agree. Never mind teenagers, but people have always yielded to money and power over time. Who isn’t beleaguered by the needs of life? You can’t blame The White Haired Girl for marrying Huang Shiren.” Another said, “Women nowadays want to marry money, and they don’t care who owns that money.”

In an informal Internet poll people were asked: Do you think that the White Haired Girl should marry Huang Shiren? In the poll, 40.6 percent said “Yes” agreeing with the statement — if you are going to marry someone, it should be some rich man?; 39.9 percent said, “No,” agreeing with the statement “your marital choice should not be based solely on money?; and 19.5 percent said “Not sure.”

Taking Tiger Mountain By Strategy

“Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy” is one of the Eight Model Operas. The main storyline of Tiger Mountain follows the revolutionary Yang Zirong who infiltrates an encampment of Nationalist soldiers (inevitably labeled “bandits”) and then springs a bloody ambush. Set in 1946, the communist insurgency was three years away from overthrowing the Nationalist government and seizing power. Brian Eno named one of his albums and the title track on the album "Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy." He claimed to have seen some postcards of a revolutionary Chinese opera in a shop window in the early 1970s when he made the album.

Describing one of the songs from the opera, Matthew Robertson wrote in The Epoch Times, As is typical in these performances, the first part of the song consists of reflections on nature...a few lines about snow, mountains, forests, and courage. At about three minutes into the song the joint aria begins, with the title, “Welcome spring, bringing change to the world.” [Source: Matthew Robertson, The Epoch Times, February 11, 2013]

And then it gets down to business. One singer sings: “The Party gives me wisdom, gives me courage.” He goes on: “To defeat the bandits, I first dress as one.” Another singer then rejoins for the second half of the duet: “Raid the bandits’ lair, absolutely turn it upside down!” A bright red decorative cloth is projected onto the back wall and columns as the camera pans out. Later in the story the communist heroes “destroy the bandits and capture the bandit chieftain Vulture,” according to a synopsis of the original libretto, which was “carefully revised, perfected and polished to the last detail with our great leader Chairman Mao's loving care.”

In 2013 a Canadian performed "Taking Tiger Mountain By Strategy" at CCTV New Year Show, the biggest television event of the year in China. Robertson wrote: "Canadian opera virtuoso, Thomas Glenn and Yu Kuizhi, a well-known Beijing opera singer, co-sung a section from “Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy.” A red opera had not been on the Spring Festival Gala for three decades. “I don’t feel like this piece was chosen to ignite any sort of controversy,” he said. “I think the piece was meant to show an intercontinental friendship... certainly I’m ignorant of any propagandistic aspect.”

Revolutionary Theater After Mao

new Red Detachment of Women

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: The political situation and, consequently, cultural climate changed drastically after Mao Zedong’s death and the fall of the Gang of Four in 1976. In the same year a list of 41 Peking operas was published, which could now be included in the repertory of opera troupes instead of the model dramas and ballets. Gradually, interest in traditional forms of theater was revived and actors and teachers who were disgraced during the Cultural Revolution could return to their work. In this new, more open climate, dramatists and other theater artists have been able to handle the traumatic decades of Chinese history. At the same time, doors have been opened to Western influences including Western plays. Classics like Shakespeare and Moliére as well as more modern classics, such as Brecht and Becket, have been staged regularly. In the mid-1990s Arthur Miller directed his play Death of a Salesman in Peking. **

[Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki **]

In a review of the book, “Red Legacies in China, Xing Fan wrote: “In Chapter 5, “Performing the ‘Red Classics’,” Xiaomei Chen examines the negotiation between presenting the past and serving the present through three grand revolutionary music and dance epics: The East is Red (1964), The Song of the Chinese Revolution (1984), and The Road to Revival (2009). Weaving the three pieces’ political and historical contexts into a comparison of their themes, creative processes, and styles, Chen analyzes a series of ironic paradoxes in the red legacy of the PRC’s state performance culture. [Source: Xing Fan, Review, MCLC Resource Center Publication, March, 2017; Book “Red Legacies in China: Cultural Afterlives of the Communist Revolution” (Harvard University Asia Center, 2016), edited by Jie Li and Enhua Zhang]

Chen notes that a tailored, revised, and “correct” past is presented to legitimize the present, despite China’s shift from socialist revolution in the 1960s to semi-capitalism in the reform era, and then to capitalism in the early twenty-first century. She further examines the historical variations that emerged from an unwavering faith in a massive theatrical form: the cult of Mao, the cult of Deng, and finally the cult of the production director. The chapter also remarks on the advantage of possessing sufficient artistic and financial resources in the constant pursuit of spectacles, which evolve into the visual extravaganzas Chen terms “post-epic theatricality”.

Then there is the kitschy side of the genre. Describing a show for tourists in the “red tourist” town of Yenan, where Mao lived after the Long March, Alice Su wrote in the Los Angeles Times: Stars showered from the ceiling as actors suspended by ropes ran through the air. An unseen man's voice boomed through the theater: "I have followed this red flag, walking thousands of kilometers with the faith of a Communist Party member in my heart!" Here in the hallowed ground of northern Shaanxi province, the Chinese Communist Party's founding myths are on full display. A musical performed twice daily portrays revolutionaries rescuing China from foreign invasion and corruption: Conniving generals coerce Shanghai women dressed like flappers to dance. Communist students are hanged. Trapeze artists in military fatigues flip upside down amid flurries of fake snow. “It is rousing agitprop underscoring a slogan that has saturated the nation in recent years: "Buwang chuxin, laoji shiming" — "Don't forget our original intentions; hold tightly to the mission." [Source: Alice Su, Los Angeles Times, October 22, 2020]

White-Haired Girl Directed by Peng Liyuanm Xi Jinping’s Wife

In the mid 2010s, Peng Liyuan, wife of Chinese leader Xi Jinping, served as artistic director for a new traveling production and revival of The White-Haired Girl. Chris Buckley wrote in the New York Times’s Sinosphere in 2015: The Ministry of Culture said it had revived the story in response to Mr. Xi’s own landmark speech in 2014 on the role of the arts in China, when he demanded politically wholesome art cleansed of decadence. The revival had its premiere in Yan’an in November 2015 and performances are planned in nine additional Chinese cities, culminating in Beijing in mid-December, the Ministry of Culture said in an emailed statement. “This is taking concrete action to implement General Secretary Xi Jinping’s important speech and ‘opinions’ ” on art and literature, the ministry said. “The revival of the opera ‘The White-Haired Girl’ under new conditions, and its widespread dissemination, has major practical significance and far-reaching historical significance.” [Source: Chris Buckley, Sinosphere, New York Times, November 10, 2015]

“The leadership undoubtedly sees it as a classic of the Yan’an repertoire, to remind people of the glories of the Yan’an days,” Mr. Clark said. “The story had “a symbolic value, as representing a time when the Communist Party was pure,” Mr. Clark said. But young audiences were unlikely to flock to it, he predicted. “It’s just an impossible task, given the Internet and everything else,” he said. “It comes across like someone standing in the street in a Yan’an-era uniform.”

If Mr. Xi needs more reason to favor the revival of the opera, there is also the fact that his wife, Peng Liyuan, is an artistic director for the new production, according to the Ministry of Culture. Well before Mr. Xi came to power, Ms. Peng was more famous than he in China as a singer of stirring party and military ballads, and she played the lead role in “The White-Haired Girl” during the 1980s, when she was a performer in a People’s Liberation Army troupe. Ms. Peng is now president of the People’s Liberation Army Academy of Art. “During her busy schedule, Prof. Peng Liyuan on multiple occasions found time to appraise and guide revision of the performance,” the ministry said. “She also gave classes to the main actors, personally giving demonstrations during their rehearsals.”

“For some Chinese, the entanglement of a party leader and his spouse in determining artistic values through a “model opera” is likely to bring disquieting echoes of the past — namely Mao Zedong and Jiang Qing. As a rising official, Mr. Xi was friendly with the writer Li Mantian, who wrote the story that was an inspiration for the opera. “I’ve talked with several artists, and whenever I ask what the most pressing problem in literature and the arts is, they all say one word, ‘shallow,’ ” Mr. Xi said in his talk to artists and writers in 2014. “Some works mock the majestic, warp the classics, subvert history, uglify the masses and heroic figures. Some make no distinction between right and wrong, good and evil.” “The Ministry of Culture said that the latest revival incorporated several new elements. The script was revised at least 10 times, it said — a reflection of the official attention given to the production. The new show features “3D” visual effects, which officials said would add authenticity. It is unclear whether Mr. Xi will attend any of the performances.

Das Kapital for the Chinese Stage

new Red Detachment of Women Director He Nian “ best known for his stage adaptation of a martial-arts spoof — plans to do a stage version of Das Kapital — Karl Marx, dense and heavy tome on the political economy — with inging and dancing and elements from Broadway musicals and Las Vegas shows. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, March 17, 2009]

He told the Wen Hui Bao newspaper, “The particular performance style we choose is not important, but Marx's theories cannot be distorted.” Zhang Jun, an economics professor at Shanghai's prestigious Fudan University, is being drafted in to ensure the production is intellectually rigorous.

He said the play will be set in a company and will document the progress of its workers. In the first half they realize their boss is exploiting them and begin to understand the theory of surplus value. But far from uniting, as Marx enjoined them in the Communist Manifesto, some continue to work as before, some mutiny and others employ collective bargaining.

Das Kapital is not known for having fetching characters or a gripping plot. However it is not the first someone has though of making a play out of it. . A Japanese writer and translator is said to have adapted Das Kapital for the stage in the 1930s, and the result was subsequently translated into Chinese. In the mid 2000s a staging by a German theater group — in which each theater goer was given copy of Volume 23 of the Collected Works of Marx and Engels for each theater-goer — was described by the newspaper Suddeutsche Zeitung as mostly ‘something of a lecture at times dry and boring.”

China’s Entertainment Soldiers

The Atlantic reported: “With all of the chatter surrounding China's "entertainment soldiers," it's worth asking: what are they? In fact, there is no such thing as an "entertainment soldier," at least not in official documents or PLA regulations. Authorities are more likely to refer to such personnel as "literary, art, and sport performers in the army. The word "soldier" is not entirely correct either. In China, both on-duty and reserve soldiers can be categorized into two types : army officers and civil officers. The former are required to undergo military training, and are subject to being sent to the battlefield in wartime. By contrast, the civil officer corps, to which most of the entertainment "soldiers" belong, do not attain any military rank. [Source: Tea Leaf Nation, The Atlantic, August 14, 2013 ]

“The PLA's penchant for cultivating and promoting literature and art work dates as early as 1927. When Chairman Mao was leading his Autumn Harvest Uprising, he ordered, "Putting on art performances is one of the missions for committees of regiments, battalions and companies at each level." A year later, the propaganda team of the Fourth Red Army was established and later admitted as a formal team within the Communist Party's military system. The team was responsible for PLA propaganda, and for providing entertainment such as singing and dancing for soldiers when there was no battle to fight as well as for writing and acting out drama.

“Ever since, the Communist Party has allocated plentiful resources to its "entertainment army" units. During World War II, entertainment soldiers, Regarded as "helpful in boosting morale," were given so much attention that most army units at the regiment level and above had their own drama clubs and art performer troupes. The Party has been a stalwart source of support, but the Chinese public appears to question whether entertainment troupes have outlived their usefulness.

“The PLA has not released details of its military spending, so there are no accurate statistics about PLA entertainment expenditures. The consensus guess is that the current scale of PLA entertainment troupes exceeds 10,000 people while the total cost of keeping the entertainment soldiers and army units of low operational capacity could amount to 10 billion RMB (about US $1.6 billion).

Image Sources: Asia Obscura

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021