HIP HOP IN CHINA

Hip hop is known as “xi ha” in Chinese — as close as the Chinese language can get to pronouncing “hip hop.” The music form is becoming increasingly popular among urban youth and rural youth who have access to it and it draws fairly large crowds to festivals and venues like the Mako, a club in Beijing , where it is performed.

Hip hop in China has been tamed, cleaned and manipulated by government authorities, who give air play to artists that glorify China and celebrate popular tourist attractions rather than mock the police, glamorize gangsta violence and down and dirty sex. Government-authorized hip hop groups release albums that bear stickers that tell fans to share the music with their parents. They also do public service announcements on radio, exhorting people to have pride in the country, respect elders and do their bit to clean up the environment.

Chinese pop music expert Helen Feng told the Six Tone: One change that has occurred in China in the 2010s was the “commercialization of hip-hop. I wouldn’t say it’s the popularization of hip-hop, because hip-hop has been around for quite some time in China. It’s already had its stages of being quite popular, but in those days, it wasn’t exactly digestible for all; it wasn’t exactly cotton candy. It was often very confrontational toward authority, staying primarily within its counterculture kind of world. Now, you can see on the TV program [“The Rap of China”] and everything else that it’s becoming more of a commercial product; it’s become like any other music type, sticking to particular archetypes of what youth is. The messenger has become more important than the message. That’s how commercialization happens: when you’re creating stars rather than messengers. I’m a huge fan of Gil Scott-Heron, who essentially invented hip-hop. That’s an example of the messenger not being as important as the message. For a long time, it was all about the message, but now it’s more about the messenger, more about the pop star. I think in China that’s happened as well, in hip-hop. [Source: Kenrick Davis, Sixth Tone, September 1, 2017]

“Shuo chang” , Chinese word for “rap,” translates to ‘speak sing’ and is a loaded term. Jimmy Wang wrote in the New York Times, “It also describes a contentious subject for musicians, producers and fans in China.Hong Kong, mainland and Taiwanese pop stars who have their own spin on hip-hop dominate the mainstream here. Many tack high-speed raps onto the end of their songs, even ballads, and consider themselves rappers. The blogger Brendan O’Kane said that my impression (possibly wrong) is that people here who are into hip-hop would look upon the use of shuochang as a sign that someone was not part of the scene.” [Source: Jimmy Wang, New York Times, January 23, 2009]

Making Chinese hip-hop is a relatively profitless — and often subversive — activity. Wong said, “But if you want to take the next step to becoming mainstream, you hit a wall. If you aren’t singing their type of stuff or aren’t incredibly rich, they won’t sign you.” Additionally, because of rampant music piracy, the corporate support of artists approved by powerful producers is one of the few ways to generate revenue for musicians here. Because corporate advertisers almost always seek out pop stars who have been given the blessing of producers representing state-run media, the underground music scene has had to live off the enthusiasm of young music aficionados without ever being able to gain backing to spread beyond nightclub walls.

See Separate Articles: MUSIC, OPERA, THEATER AND DANCE factsanddetails.com POP MUSIC IN CHINA: SHANGHAI JAZZ IN THE 1920s TO K-POP IN THE 2020s factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE POP MUSIC INDUSTRY factsanddetails.com BIG CHINESE POP ARTISTS: FAYE WONG, LUHAN AND THE FOUR KINGS OF HONG KONG factsanddetails.com ; ROCK IN CHINA: HISTORY, GROUPS, POLITICS AND FESTIVALS factsanddetails.com ; CUI JIAN: HIS MUSIC, CONCERTS AND TIANANMEN SQUARE factsanddetails.com ; PUNK ROCK AND UNDERGROUND MUSIC SCENE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; WESTERN POP MUSIC IN CHINA: WHAM, BJORK, THE STONES factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: 2009 Wall Street Journal article about Beijing Underground scene online.wsj.com ; ; 2009 New York Times article on Hip Hop nytimes.com Foreign Policy article on Underground bands foreignpolicy.com Chinese Pop Music Inter Asia Pop interasiapop.org; Sinomania, with old postings but still online sinomania.com ; Wikipedia article on C-Pop Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on Cantopop Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on Mandopop Wikipedia ; Chinese, Japanese, and Korean CDs and DVDs at Yes Asia yesasia.com and Zoom Movie zoommovie.com ; Book about Chinese pop music: ”Like a Knife” by Andrew Jones.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS AND MUSIC: “Like a Knife: Ideology and Genre in Contemporary Chinese Popular Music” (Cornell East Asia Series) by Andrew F. Jones Amazon.com; “The Evolution of Chinese Popular Music” by Ya-Hui Cheng Amazon.com ; “Red Rock: The Long, Strange March of Chinese Rock & Roll” by Jonathan Campbell Amazon.com “Beijing Underground: Cracks on a Great Rock Wall” by David James Hoffman Amazon.com; “Cui Jian: Rock and Roll on the New Long March Road” by Cui Jian (CD) Amazon.com “Never Turning Back” by Jian Cui (poetry book) Amazon.com; “Inseparable, the Memoirs of an American and the Story of Chinese Punk Rock” by David O'dell Amazon.com; “Wham! The Edge Of Heaven / Blue (live in China); w/ original Picture Sleeve. by Wham! (Vinyl) Amazon.com; “Rocking China: Music Scenes in Beijing and Beyond” by Andrew David Field Amazon.com; “Music in China: Experiencing Music, Expressing Culture (Includes CD) by Frederick Lau Amazon.com; The Very Best Of Chinese Music by Han Ying, Various Artists, et al Amazon.com; “The Music of China's Ethnic Minorities” by Li Yongxiang Amazon.com; “Music, Cosmology, and the Politics of Harmony in Early China” by Erica Fox Brindley Amazon.com; “Chinese Music and Musical Instruments” by Qiang Xi (Author), Jiandang Niu Amazon.com

History of Hip-Hop in China

According to AFP: Hip hop is still marginal in China’s music scene, dominated by love songs, imported pop and patriotic tunes dating from the era of Mao Zedong. Mainland China’s first major rap collective Yin Tsang released their first album in 2003, shunning politics in favour of goofball intonation and uplifting anthems and their songs still receive regular airings on Chinese radio. [Source: AFP, December 31, 2015]

Yi-Ling Liu wrote in Guernica: The earliest hip-hop music in China emerged as a niche subculture, concentrated in large cosmopolitan centers like Beijing and Shanghai. Over the past decade, the rise of a generation hyper-connected by social media apps like WeChat, QQ Music and Douyin, and with greater spending power and exposure to Western music, has enabled homegrown hip-hop to spread throughout the country. [Source:Yi-Ling Liu, Guernica, August 29, 2018]

Homegrown hip hop was still a new phenomena in China in the 2000s. While American rappers like Eminem and Q-Tip have been popular in China since the 1990s, home-grown rap didn’t start gaining momentum until a decade later. In 2003, Mao’s birthday was celebrated with a CD of Mao slogans shouted out to rap music beats. Among the highlights was a spirited version of the “Two Musts”—“to preserve modesty and prudence” and “to preserve the style of plain living and hard struggle.”

Early rappers had difficulty adapting their tonal language to rap’s rhythms. Some of the biggest promoters of the sound were American English teachers. “The big change was when rappers started writing verse in Chinese, so people could understand,” Zhong Cheng, 27, a member of the group Yin Ts’ang told the New York Times, “Before that, kids listened to hip-hop in English but maybe less than 1 percent could actually begin to understand.” Zhong wa sraised in Canada but born in Beijing, where he returned in 1997.[Source: Jimmy Wang, New York Times, January 23, 2009]

Since the mid 2000s, Chinese hip-hop scene has quickly grown. Hiphop.cn, a Web site listing events and links to songs, started with just a few hundred members in 2007; in 2008 it received millions of views, according to one of the site’s directors. Dozens of hip-hop clubs have opened up in cities across the country, and thousands of raps and music videos by Chinese M.C.’s are spreading over the Internet.

According to The Atlantic: In 2017, the television series Rap of China debuted to 100 million views in the first four hours of its release. Prior to the show, rap had existed in China only in underground circles; it had become mainstream overnight. But its ascendance to the realm of pop culture would have dire consequences for freedom of speech in the country. A year later, as Rap of China headed into its second season, the Chinese government imposed widespread restrictions on the country’s nascent rap scene. It blacklisted 150 rappers. References to hip-hop culture were banned from appearing in all media sources, including television and movies. [Source: The Atlantic, Oct 11, 2019]

Squeaky-Clean, State-Endorsed Chinese Hip Hop Groups

Real gritty, urban hip-hop doesn’t get that much state media exposure. Few hip-hop artists have been on the annual Chinese Lunar New Year gala, which I watched by half a billion people. What often passes for hip hop are high-speed raps tacked onto the end of their songs, even ballads, by Hong Kong, mainland and Taiwanese pop stars who consider themselves rappers.

“Jay Chou, a popular pop singer turned rapper from Taiwan who has been featured in advertisements for Pepsi, Panasonic and China Mobile, is the archetype of a mainstream performer here. Clean-cut and handsome, he appeals to a sense of nationalist pride. His hit song Huo Yuanjia is based on a patriotic Chinese martial artist glorified in Chinese textbooks for traveling the country to challenge foreigners in physical combat.” He is one of the few “hip-hop” that have appeared in the Chinese Lunar New Year gala. [Source: Jimmy Wang, New York Times, January 23, 2009]

Fans of Chou vehemently assert that his music is hip-hop, while denigrating groups like Yin Tsar. “I don’t know what groups like Yin Tsar are trying to do,” Hua Lina, a 35-year-old accountant told the New York Times. “They dress like bums, and sometimes they take off their shirts at performances, screaming like animals. Their lyrics are dirty — why would I want to pay to see that?”

See Luhan and TFBOYS in Separate Article BIG CHINESE POP ARTISTS: FAYE WONG, LUHAN AND THE FOUR KINGS OF HONG KONG factsanddetails.com

Hip-Hop, Self Expression, Social Commentary and Foul Language in China

Chinese hip hop

Many hip hop artist are drawn to music as a means of self-expression, A 24-year-old rapper who calls himself Shung Zi told the China Daily, “Hip-hop is free and I talk about my life, what I think about and what I feel...It seems that I have found a way to express myself and my own character, which I didn’t learn from school. Among the raps he performs with his group Yi He Tuan ( a reference to the Boxer Movement from 1900) are “Telling the Story of Ordinary People”, about his experiences growing up in Beijing hutongs, and “Niu Zi”, a girl he secretly loved.

Shung Zi said, “It’s a fast-moving time and hip-hop music is well-received by listeners. We put Beijing dialect in hip-hop just to make the language and unique local Beijing story heard by more people.”

“Hip-hop is free, like rock “n’ roll — we can talk about our lives, what we’re thinking about, what we feel,” Wang Liang, 25, a popular hip-hop D.J. in China who is known as Wordy, told the New York Times. “The Chinese education system doesn’t encourage you to express your own character. They feed you stale rules developed from books passed down over thousands of years. There’s not much opportunity for personal expression or thought; difference is discouraged.” [Source: Jimmy Wang, New York Times, January 23, 2009]

Some Chinese rappers address what they see as the country’s most glaring injustices. As Wong Li, a 24-year-old from Dongbei, says in one of his freestyle raps: “If you don’t have a nice car or cash/ You won’t get no honeys/ Don’t you know China is only a heaven for rich old men/ You know this world is full of corruption/ Babies die from drinking milk.” Wong often performs in a downtown Beijing nightclub and uses Chinese proverbs in his lyrics to create social commentary. Wong, who became interested in hip-hop when he heard Public Enemy in the mid-‘90s, said rapping helps him deal with bitterness that comes with realizing he is one of the millions left out of China’s economic boom. “All people care about is money,” he said. “If you don’t have money, you’re treated like garbage. And if you’re not local to the city you live in, people discriminate against you; they give you the worst jobs to do.” In the 2009 hit Hello Teacher, Yin Tsar, one of the hip-hop scene’s biggest acts (its name means The Three Shadows) rails against the authority of unfair teachers, and it does so in quite nasty language, It goes: “You say you’re a role model but you spit on the ground outside The only cunting thing you know how to do is phone my father You’re shameless and useless Do whatever you want but don’t touch my CD player You fucking cunt I’ll listen to music in class if I want to. I’ll do my math homework in writing class. I drew a big cock in my copy book, that’s what I think of you.”

In response to the New York Times’s assertion that “many students and working-class Chinese” are rhyming about the “bitterness that comes with realizing — [they are] left out of China’s economic boom.” blogger Brendan O'Kane said: “This is horseshit. The angry Chinese rap I’ve heard is generalized teenage angst with no attempt at social commentary. The most “daring” rap I’ve heard is predicated on schoolboy puns about smoking pot.” O’Kane wrote a typical attempt at social commentary, in this case from the group Yin Tsar goes: “Cabs come in 1.2 kuai and 1.6 kuai prices/ The traffic’s usually not bad, but sometimes there are traffic jams. / You don’t have to worry about restaurants — roast duck and zhajiang noodles/ Or Gui Jie to eat hotpot. There are too many choices, oh my god!” O’Kane said a good example of song with political content is Yin Tsar’s “Beijing Evening News”, which goes: “Big officials and leaders park outside night clubs Girls hiding in the toilet Whiskey and duck neck Models and starlets Sitting in a private room with stupid dicks Cops patrolling, Dongbei pimps Lots of college girls But student IDs get no discount Beijing is building But the people are changing Who is responsible for all of this?” [Source: Brendan O'Kane of bokane.org]

Impact of Government Control on Hip Hop in China

In 2015, a few years after Xi Jinping came to power, China’s Ministry of Culture blacklisted 120 songs — many of them hip hop numbers — for “trumpeting obscenity, violence, crime and harming social morality” and banned some hip hop acts from performing. Yi-Ling Liu of the BBC wrote: “Once, it felt like there was a cacophony of rap voices cutting across different ideologies, geographies and socio-economic classes — creatively competing for the hearts and minds of young Chinese. Chengdu rappers, Chongqing rappers and Changsha rappers. Rappers from the coasts of Guangzhou and the highlands of Gansu. Glitzy, cosmopolitan tunes from Shanghai and scrappy, rural tempos of the Northeastern “hanmai”. Hong Kong rappers, such as Fotan Laiki and Doughboy, spitting rhymes about a hometown in flux. Diaspora rappers like Bohan Phoenix, singing from the cracks of China and the United States. [Source: BBC, Yi-Ling Liu, November 6, 2019]

“Today, the Chinese cipher seems to have ossified into binary themes — love and hate, anti-China vs pro-China, fervent nationalism vs treason to the nation — making it a zero-sum game in which conflict can only be resolved by the defeat of one side by the other. Artists like Wang, Melo and Vava, among so many others, seem have forgotten that the cipher is about competition, but also community, creativity and authenticity.

“Instead of creating a unique sense of self and perspective, they have decided to toe the line, parroting the Chinese authorities’ message. This is not to say that all Chinese pride is uniformly expressed. Rapper GAI leading chants of Long Live the Motherland at the Spring Festival gala sponsored by state media is a very different brand of patriotism from the Higher Brothers’ breakout track Made In China. On one hand, the Higher Brothers’ song — about how Western products are now made in China — is indeed a bold assertion of Chinese pride. But the rappers are not boasting about China’s national sovereignty, replete with a red and yellow flag, but about the “jar of hot sauce so spicy that foreigners start to burn”.

“The lyrics aren’t Mandarin, the language of national television, but Sichuanese, rich with rising and falling tones, which has great lyrical flow. Unlike the knee-jerk nationalism of Melo’s latest Instagram post, this playful, creative, hyperlocal pride is for the spicy food and free-wheeling attitude of its capital, Chengdu.

“Two years ago, I visited Chengdu and sat in the studio of a group of young, aspiring rappers — TSP, from the outskirts of Sichuan; Rainbow and Skinnyoyo, from the flat, central grasslands of Xi’an and Shandong; Kong Kong, from the southern coast of Hong Kong; and Young13DBaby and Fendi Boi, from the northern mountains of Lhasa and Gansu. As we sat together, shaking our heads to one of the group’s latest collaborations, I was struck by how smoothly they had woven together lyrics in Tibetan, Cantonese, Sichuanese, and Mandarin.

“This scene of six boys, from six different regions of a nation of more than one billion, nodding their heads in unison to the beat of the music they had created together on their own, was the closest I have seen the Chinese cipher in its most platonic form — playful, inclusive, malleable — one song yielding the rich plurality of Chinese language and identity.

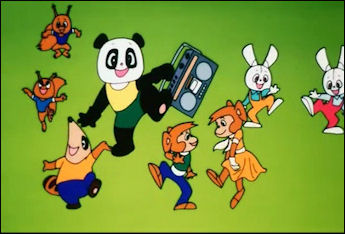

Chinese Propagandists Use Animated Rappers to Convey Their Message

In 2016, Associated Press reported: “What's the world's largest propaganda organ to do when it finds itself struggling to get TV drama-obsessed young Chinese to pay attention to the latest raft of Communist Party slogans? “Standing over a video-editing computer on the third floor of the Xinhua News Agency headquarters, Li Keyong is convinced the answer lies in a cartoon character rapping while performing the 1990s dance move known as "raising the roof." "Look at how we got this bald fat guy and a tiny cute girl singing together," said Li, a deputy director of Xinhua's All-Media Service, as he watched two animated characters promoting President Xi Jinping's "Four Comprehensives" political doctrine with a mix of high-tempo rap and choir singing in what might be called a neo-Communist hip-hopera. "We thought, 'With such an abstract political theme, it's difficult for young people to accept," Li said. "Young people want fun, they want joy." [Source: Associated Press, March 4, 2016]

“The fun and joy that Xinhua is searching for reflects a quandary facing China's leadership: As Xi navigates a difficult phase of his administration, his messaging machine — for decades one of the Communist Party's most crucial levers of power — has been struggling to make itself heard. Carrying echoes of the party-promulgated "Red Songs" that drowned out folk music 50 years ago, the mix of click-baiting animation and old-fashioned propaganda is a reminder that, for all its ambitions of becoming a savvy, media industry leader with global appeal, Xinhua's core mission is to serve as the party's mouthpiece, something Xi reinforced last month in a politically charged newsroom visit.

Xinhua officials spoke about their challenges and argued that it's their delivery, not the party's message, that needs a refresh at a time when Chinese youth are glued to their smartphones watching streaming dramas and game shows. "We used to be number one, the biggest," said Qian Tong, a former diplomatic reporter who, like Li, is a deputy director of Xinhua's All-Media Service, a new newsroom division formed in 2014 to organize the agency's efforts penetrating the online market and manage social media. The Associated Press interviews with Li and Qian were the first with a foreign media outlet about the division's work.

“On a recent morning Li introduced employees mostly in their 20s and plucked from across text, photo and Web departments. One bearded graphic artist worked in Photoshop on the agency's yet-to-be-unveiled mascot, which vaguely resembled a slimmed-down blue Teletubby clutching a microphone. Top Xinhua officials are convinced they struck gold with the videos, Li said. He said his biggest hit, with lyrics like "Repeat after me: four comprehensives, four comprehensives, party-building is the key" has attracted 70 million views and appeared on thousands of online accounts.

“The video has drawn a deluge of responses — not all positive, Li acknowledged. On Xinhua's Weibo account, many found the video catchy while others complained that too much propaganda material had been forced into state media during the Lunar New Year period. One user suggested the lyricist who came up with the line "four, four, four, four, four comprehensives" had obsessive-compulsive disorder, and a propaganda official from China's Inner Mongolia region offered dubious praise, calling the song "bewitching and brainwashing." What pleased him most, Li said, was that final sentiment, when commenters say they could not get the song out of their heads, or that they sometimes found themselves involuntarily humming it.

Chinese Hip Hop Groups in the 2000s

Dragon Tongue is one of the top hip hop labels in China. Among its artist are the Dragon Tongue Squad, Sketch Crime. MC Webber and Kung Fu. When Webber wrote a song condemning people who had grown rich by cheating people authorities asked the rapper to write about something more positive. Kung Fu is perhaps the most government-friendly group. It warns teenagers not to act on impulse.

PTS, a hip hop group from Inner Mongolia, has drawn some attention in Beijing. They rap about the grassland from where they come and mix their local language and Mandarin in their raps. In their rap “Say” they chant “We grow up the arms of the sky. We hear our dignity and dreams deep in our heart. We don’t care about vanities, but making music of our own choice.” Suhe, the 24-year-old front man of PTS, told the China Daily, “Though we live in the remote grasslands, we’ve al grown up watching the same cartoons and TV shows as other Chinese. “We are proud of out language which goes perfectly with the hip-hop beat.”

“The group Yin Ts’ang (its name means hidden), one of the pioneers of Chinese rap, is made up of global nomads: a Beijinger, a Chinese-Canadian and two Americans. The group’s first hit was In Beijing, from the band’s 2003 debut album, “Serve the People” (Scream Records); the title is a twist on an old political slogan. It sets a melody played on a thousand-year-old Chinese fiddle called the Erhu against a hip-hop beat that brings Run D.M.C. to mind. The song, an insider’s look at Beijing’s sights and sounds, took the underground music scene by storm, finding its way into karaoke parlors, the Internet and even the playlist of a radio station in Beijing.” There’s a lot of cats that can rap back home,” said Jeremy Johnston, a member of the group and the son of a United States Air Force captain, told the New York Times. “But there’s not a lot of cats that can rap in Chinese. Johnston moved to Beijing in the late “90s because, he said, it was the thing nobody else was doing. [Source: Jimmy Wang, New York Times, January 23, 2009]

After seven years together, Zhong Cheng, the Canadian in the group and Johnston of Yin Ts’ang still struggled to pay the bills, but they hadn’t stopped making hip-hop, which they produced under their own independent label, YinEnt, in the late 2000s. Explaining how the group got started, Zhing told the New York Times, “When I got here and met Jeremy, we were both so inspired by these people,we were like, “Let’s drop some Chinese rhymes for the locals,” and our Chinese friends were like, “There are no Chinese rhymes!,” and we were like, “That’s crazy!” From that day, we haven’t stopped rhyming.”

Chengdu: Ground Zero for Hip Hop in China?

Chengdu in Sichuan Province is — or was — known for being a major hip hop center in China. Yi-Ling Liu wrote in Guernica: “Chengdu-based groups like the Higher Brothers, Fat Shady, and Ty were the face of a playful, provocative style — influenced by genres like trap — that was all their own. In Chengdu, the rent was cheap, the food was good, and people were open to artists hoping to make a living out of their music.[Source:Yi-Ling Liu, Guernica, August 29, 2018]

“From the outside, Poly Center appears to be one of many dull, nondescript office buildings lining the streets of the Chinese city of Chengdu. But inside, on the twenty-first floor that autumn night in 2016, the air was thick with laughter, strobing multicolored light, and the muscular thud thud thud of the bass was booming from the speakers. Young people leaned against the walls of the cramped corridors, taking hits of laughing gas from candy-colored balloons before diving back into one of three clubs in the vicinity. At the end of the hall was...NASA, Chengdu’s hottest hip-hop club, where an MC freestyled for the sweaty crowd.

“It is no surprise that” Chengdu’s “combination of financial power, creativity, and free-wheeling youth with something to say — three crucial elements to the rise of hip-hop culture in New York City in the 70s, according to Yale professor Nicholas Conway — would enable hip-hop’s rise” there. “Many songs are about money: wanting it, hating it, making a lot of it, throwing it around. The Higher Brothers’ name refers not to drugs but to Haier, China’s largest home appliance manufacturer. A line-up of Higher Brothers song titles reads like a teenage boy’s wishlist: “7/11,” “Black Cab,” “Room Service,” “Chanel,” and “Rich Bitch.” Their breakout track, “Made in China,” is a song about how Western products — chains, gold watches, toothpaste, umbrellas, and now, hip-hop — are made in China.

“The song is a bold assertion of Chinese pride, a comic riff on Western stereotypes of the quiet and inscrutable Oriental. “What are they even saying?” a whiny, American voice asks over a mandolin at the beginning. “Sounds like they’re just saying ching chang chong.” These sentiments bear no resemblance to the knee-jerk dismissal of the West that populates state-run media. The rappers are boasting, not about the nation’s large GDP or hefty set of military arms, but about the “mah-jongg set on the table” and the “jar of hot sauce so spicy foreigners start to burn” that define daily life in Chengdu. The lyrics aren’t in Mandarin, the language of classrooms and national television, but in Sichuanese. Many rappers expressed to me that Sichuanese, rich with rising and falling tones, has better “flow” than Mandarin, and that this allows for greater lyrical experimentation.

““I grew up on Chinese hip-hop, and I never messed with it because it never felt authentic,” said Jaeson Ma, co-founder of the American media company 88Rising, which discovered Higher Brothers. According to Ma, rappers in Asia have tried too hard to imitate what they were seeing in Western music videos instead of than embracing and remaking hip-hop culture as their own. But when Ma heard the Higher Brothers for the first time, he was impressed. “They’re reppin’ the city and the dialect. They had their own personalities and their own style.” Chengdu’s new crop of artists embrace their city and dialect proudly. “We wanted to become city heroes in the same way Drake was for Toronto,” Li Erxin, a member of the newly-formed hip-hop trio ATM, told me. ATM’s breakout song, “Local,” is one of many odes to Chengdu that have been written in the last year, alongside China-born, U.S-educated rapper Bohan Phoenix’s “3 Days in Chengdu,” a 12-minute chronicle of his return to the city.

To read the entire an article check Guernica guernicamag.com or MCLC Resource Center u.osu.edu/mclc

Changsha Hip-Hop

On a performance by C-Block, a popular hip-hop group in Changsha in Hunan Province that rapped in the local Changsha dialect, Tim Jonze wrote in The Guardian:. “The first thing I noticed about C-Block was the crush to get in. Queuing seemed an alien concept and I swiftly found myself being swept towards the doors in a sea of excitable Chinese teenagers. In the midst of this makeshift game of sardines I met Dingding, who spoke excellent English with an old fashioned cockney lilt, and told me — admittedly I’m taking her word for this — that she was Changsha’s first blogger, and the reason why at least half of the audience had come tonight. [Source: Tim Jonze, The Guardian, October 7, 2014]

“Watching C-Block is riotously good fun. Pitched somewhere between a boy band and a rap act, they swing from singing what sound like a rough-edged, East 17-style love songs to rapping over more aggressive, Chief Keef-like beats (perhaps this explains the reason why their fanbase have an equal male/female split, although to be honest both genders actually seemed to prefer the more boy band-orientated numbers). C-Block’s songs, Ren Li had explained beforehand, are about “everyday Changsha life … not wanting to work, or not wanting to be the person other people expect you to be”. Although Li didn’t think the songs have the same sense of emotional depth as some of the best US rap artists.

“What C-Block lacked in substance, though, they made up for in showmanship: throwing out basketballs and fake dollar bills into the crowd, or pulling audience members out of the front row in order to get them to rap on stage. The latter provided my favourite moment of the night, when a bashful young girl was given the mic and announced: “Motherfucker!”

“As I watched the young Chinese crowd waving their dollar bills in the air to the only English-word chorus of the night — “Get money money money! Get money money money!” — I was pretty sure it was a metaphor for something deep and meaningful about China’s increasing financial muscle and the ensuing materialism it generates … but then I thought: if you’re busy constructing metaphors during a C-Block show then you’re probably not doing it right.

IN3

IN3, according to AFP, is “a trio of brash, tattooed rappers who mix the earthy language of Beijing’s streets with classic hip hop beats. They have played packed houses in Beijing for a decade, “IN3 always had a confident swagger, but avoided strictly banned topics such as condemning the Communist Party leadership, preferring to namecheck Nike trainers and PlayStations. For the most part they avoided trouble until 2015 (See Below) and have cited The Clash and Bob Marley as influences. [Source: AFP, December 31, 2015]

“Their best-known song, Beijing Evening News, chronicles the capital’s night life, touching on drunken driving, chasing women and brawls with bar owners. It also contains broadsides against high medicine costs and school fees, heavy traffic and even poorly soundproofed apartment blocks, topics generally acceptable to state censors. “Some sleep in subway underpasses, others eat out on government expenses,” the group chant, obliquely referencing official corruption. Wearing a black baseball cap labelled “Compton” and brown Converse shoes, band member Jia Wei said: “We don't want just to criticise society, we want society to progress. I'm not giving up hip hop,” he said.

“The group saved their harshest rhymes for China's strict education system, which Jia has called the country's biggest problem. It was pilloried in probably their most outspoken track, Hello Teacher, where they threaten to draw sexually explicit doodles in their exercise books, and call on “shameless” instructors to “die quickly”.

Ironically the group was embraced for a while by the Chinese government and emdia. “One band member, Chen Haoran, studied clarinet at China’s prestigious Central Conservatory of Music. When the Olympics arrived in China's capital in 2008, local television filmed the group in the city's ancient hutong alleyways, rapping: “Beijing is your home, even foreigners speak like Beijingers, they will cheer team China on.” The same year they won praise from the state-run press which dubbed them the “bling dynasty's bad boys”. But their flow has been interrupted by ever-tighter limits on expression. Official approval for shows has been harder to come by in recent years, Jia said, while others have been shut down at the last minute.

IN3 Banned and Detained

In 2015, IN3 claimed they were grabbed by plain clothes police and detained for five days without charge as a number of their songs were banned as the Ministry of Culture. AFP reported: “Straight in at number one on the Chinese government’s banned songs chart is IN3 And number two. And three. And so on, down to number 17. The hard knocks came as China's ruling Communist Party tightens regulation of culture under President Xi Jinping, who has called on artists to “serve socialism”. [Source: AFP, December 31, 2015]

“Searching for an alternative venue, IN3 held a gig in Yunnan province, some 3,000 kilometers from Beijing, but just minutes after they landed back in the capital police boarded their flight to handcuff and hood them, Jia said. The band, whose members have previously been open about consuming cannabis, were all held on drug-related charges, Jia said. Beijing has stepped up a campaign against celebrity users which in January 2015 saw Jackie Chan’s son jailed for six months.

“Jia said he was released after a week when police found no evidence he had dealt the drug, but added he believed their music was a factor in the detention, just weeks after the blacklist was released in August. “I think we were taken in because of our songs,” he said. “We were locked into interrogation chairs and they kept the hood on us. They wanted to scare me.” Police did not respond to a request for comment.

“Their new blacklisted status means IN3 are unlikely to grace Beijing’s stages again. “Of course I'm upset. They rap about the kind of stories which happen every day to my friends,” said local fan Amy Wang.“After their release from detention, IN3, travelled to Atlanta in the United States to record at the studios of hip hop legends Outkast.

Higher Brothers, Chengdu’s Premier Rap Group

Higher Brothers is a Chengdu-based hip hop group with four members — Masiwei, DZKnow, Psy.P, and Melo. Emily Hulme wrote in Nylon: “The music of Higher Brothers pulls from a variety of influences: Masiwei cites artists such as 50 Cent, A$AP Rocky, and Migos. Much of the attention they’ve already attracted focuses on their “Chinese trap” style. But there’s definitely a nod to the mid-’90s and early 2000s in their songs like “7-11” — about the convenience store — and “Without You,” both of which feature melodic crooning over loungey loops that are themselves a throwback to ’70s-style R&B and soul. This pastiche may be a reflection of how each of the guys came to hip-hop in the first place. These days in China, using a VPN to access the outside world via the internet is commonplace, but it wasn’t always easy for them to consume foreign culture. Both DZKnow and Melo, separately, remember that their first time hearing rap music was on CCTV-5, which is China’s national sports television channel. (It’d be akin to having your mind blown by new music on ESPN.) “It was over for me,” recalls Melo of the experience. [Source: Emily Hulme, Nylon, August 29, 2017]

The center of the Chengdu scene is the rap crew CDC (also known as the Chengdu Rap House), a collective of the best in local hip-hop talent. This is where the four Higher Brothers met. DZKnow says that he moved from his hometown of Nanjing, on China’s east coast, just to join. “At the time I was a fan of CDC, so I thought Chengdu was a better place for aspiring rappers,” he recalls. Many Chengdu artists — Higher Brothers included — rap in a local dialect which isn’t easily understood even by other Chinese people. Masiwei explains that they were inspired to embrace their local tongue after watching rappers from the Southern U.S. in the Vice documentary “Noisey Atlanta.” “We realized that [using Sichuanese] is an advantage. It’s actually really cool to do it,” he says. As Masiwei notes, there are a lot of words in Sichuanese that have a sound and flavor that just don’t exist in Mandarin. The tones and the cadence are specific to the area, and they have a certain amount of hometown pride in being able to share that with the world. “Local language is the biggest influence [of Chinese culture on our music],” Melo says.

“Each of the individual members of Higher Brothers has been rapping for years. Masiwei says that in high school his mom bought a computer and he would just play around making songs. Similarly, DZKnow started out while holed up at home, recording his own voice over other artists’ beats. Then there were the public rap battles, which in Chengdu were friendly but competitive. “Only the strong survive,” says Melo, who believes the experience motivated him to hone his skills.

Lifestyle of Higher Brothers

Emily Hulme wrote in Nylon: “For Higher Brothers as a unit, things have happened fast. Less than two years ago, Masiwei, Psy.P, and DZKnow rented an apartment together, and brought in their friend Melo. Masiwei says, “We thought, ‘OK, we could make some songs together, make a mixtape, sell the mixtape, then we’ll be able to live off this money.’” Lo and behold, the plan panned out, and they’ve been selling out clubs all over China ever since. It’s gotten to the point where they can now all devote themselves full-time to Higher Brothers, no shitty day jobs required. [Source: Emily Hulme, Nylon, August 29, 2017]

“Melo and Masiwei live with their longtime girlfriends, while DZKnow and Psy.P still live in the group’s recording studio/living space. The tiny bedroom, with two sets of bunk beds, looks more like a large closet by American standards, although this sleeping arrangement would be familiar to anyone who’s lived in a Chinese dorm. “Then we have a cat,” Masiwei says fondly, gesturing to the litter box. The main room is dominated by a giant TV with two PlayStation 4 consoles side by side.

““We don’t really go out to party in Chengdu,” Psy.P says. “We just kind of stay at the studio and play games and stuff.” On the road, they can be a little more wild. But just a little. Outside of China’s first-tier cities, it can be hard to find something that to Westerners would be recognizable as “nightlife.” “I’ve been going on tour with them, too,” Larkin says, “and [sometimes] you show up at the bar and there’s nobody there on, like, a Friday or Saturday night. So you stay 10 minutes and you have one drink and you leave.” Instead, a “crazy night” on tour might be something elemental, such as at a July show in Changsha, where three people ended up fainting from the heat. Or you have instances of petty theft, like in Shanghai, when a fan stole Masiwei’s headband as he was crowd surfing. “The tour manager got super pissed,” Larkin says, “[and] was yelling at the audience.” Alas, the headband was never returned.

“For those who are wondering, Higher Brothers is absolutely not a weed reference. “No!” says Masiwei immediately when asked. When pressed, Larkin adds, “In China, that’s like…not OK.” Instead, it’s a play on the national Chinese electronics brand Haier, whose success the guys wish to emulate. It was a happy coincidence that Haier is a homophone for “higher,” which they’ve taken to mean improving and succeeding. “Go higher and higher,” says Melo when asked about his plans for the future. “Which means getting closer to my goals. I think my perfect song is always the next song.”

Higher Brothers: Seeking Success By Sucking Up to the Government?

Yi-Ling Liu of the BBC wrote: “In 2015, Chinese hip-hop group Higher Brothers learned something the hard way: be very careful when your songs turn political. The source of controversy was an anti-Uber song. “I don’t write political hip-hop,” spat out by the group’s rapper Melo. “But if any politicians try to shut me up, I’ll cut off their heads and lay them at their corpses’ feet. This time it’s Uber that’s investigated. Next time it will be you.” It led to the song being blocked by Chinese censors, and Melo called in for questioning by the local Public Security Bureau. [Source: BBC, Yi-Ling Liu, November 6, 2019]

“Since then, Higher Brothers have garnered widespread success both at home and abroad, partly thanks to landing their first American tour to promote their album Journey To The West. Alongside many of China’s rising crop of hip-hop artists, they’ve stormed onto both the local and global stage — and largely steered clear of politics.

“Until now... as the Hong Kong protests have unfolded, and as geopolitical climes have chilled both at home and abroad, many of China’s rappers have decided to voice their politics. But in stark contrast to the longstanding tradition of counter-culturalism and racial protest that has defined American hip-hop, the politics these rappers are asserting has a distinctly, one-noted nationalist tone. In response to the protests, Melo posted a picture of the Chinese national flag on his social media accounts with the caption: “Once again, I’m proud to be Chinese.” The rapper CD Rev released a diss track titled Hong Kong’s Fall. Jackson Wang, a Hong Kong-born artist, declared on Weibo that he was a “flag bearer determined to side with China”.

“Reactions have been polarised. Wang was accused of being a traitor by pro-democracy activists, then given a supportive pat on the back by Chinese state media In hip-hop parlance, the “cipher” refers to the circle of participants closing around a group of battling rappers flexing their own skills and challenging each other’s ideas to win over an audience. The cipher is about competition, but most crucially, it’s about identity, a chance for the rapper to express where they stand and what they believe in.

“At a moment in history when identifying “Chinese-ness” has never been so vigorously contested — both on a global scale and in people’s personal lives — it is no surprise that China’s rappers are stepping into the cipher. In doing so, they are raising a very basic question about identity: What does it mean to be Chinese?

“Ye Lang Disco” (“Wild Wolf Disco”) — Chinese Dummy Rap

Wujun Ke wrote in the Los Angeles Review of Books: “When a friend introduced me to the Chinese viral hit “Ye Lang Disco” (“Wild Wolf Disco”) in September 2019, I was not sure what the hype was about. Then, like thousands of internet commentators, I fell victim to the earworm. I was captivated by the song’s refreshingly folksy and unassuming sense of humor. Gem , a rapper from Changchun, performed the song in the 2019 season of Rap of China, a popular televised rap competition. Soon after, Gem found breakout success on Tik Tok. [Source: Wujun Ke, China Channel Los Angeles Review of Books, February 28, 2020]

“First released on his 2017 EP Your Uncle , the album title refers to Gem’s public persona of an aging yet cheerful and avuncular man. In October 2019, it was given fresh life when Hong Kong pop idol William Chan Wai-ting covered it in his native Cantonese. A viral sensation, the song has spawned countless covers in various regional dialects, reaction videos, and parodies of the choreography across Chinese social media platforms.

“In interviews, Gem has characterized his sound as “dummy rap” or “comedic rap” .Gem infuses his music with regional references and a self-mockery specific to his native dongbei, the northeastern region of China that includes Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning. The song is a gesture to the social cost of de-industrialization of China’s northeast. Previously a puppet state of the Japanese empire, the Northeast became a stronghold for the communist takeover in 1928 and then a pillar of Soviet-style industrialization in the Mao era. The reform-era has brought the gradual decline and abandonment of the factory ecosystem, resulting in mass layoffs of workers from industries that had once guaranteed lifelong employment and benefits. In an interview with TRILLSXXT, Gem said, “My songs are about the decline of the Northeast and a desire for rebirth. It’s kind of my wish for my hometown.”

“The song features dongbei-specific colloquialisms that toe the line between innovative and outdated. As a top-voted Youtube commenter noted in Chinese, “Tackiness taken to an extreme is paradoxically cool”. While tu literally translates to dirt, it is also a pejorative for tacky, rustic, outdated, and often associated with rural or small-town aesthetics. In the reform era, the Northeast is perceived as having fallen behind the times and as less modern than coastal cities like Shanghai and Hong Kong. The music video begins with a comedic bit where the protagonist says he’s losing signal on his dageda — a clunky, first generation mobile phone. The first iteration of the music video, low-budget and edited by the artist himself, features a series of video-samples of 90’s dance moves and film clips.

“The lyrics takes us back to the 1990s and follows the protagonist — an aging man at the precipice of a midlife crisis — to the disco. He is perhaps 40 or 50 years old, retired from dongbei state enterprises and taking whatever temporary gigs he can find. Narrated from a first-person perspective, he imagines himself as forever young with slicked-back hair and a pager on display:

bb 007 rocking that pompadour and pager, call my Patrick Swayze on the move

dj I’m the first to dance it off in the DBC, I could wear them DJ’s down

gotta hold onto the mink even if it’s 120 degrees

right now y’all move with me

Chinese Mongolian Rap

Reporting from Hohhot, Inner Mongolia, Tom Hancock of AFP wrote: “In a sprawling industrial city in Inner Mongolia, three rappers surround a microphone, dressed in the baseball caps, baggy trousers and branded trainers favoured by hip hop fans the world over. The sparsely populated region in northeastern China counts mining and milk among its main industries, and locals are more familiar with throat-singing than rapping. But members of China's Mongolian ethnic minority, whose ancestors were first united by Genghis Khan, are turning to hip hop to condemn the resources boom they say is wreaking havoc on their traditions and lands -- while avoiding the authorities' attention. [Source: Tom Hancock, AFP, September 20, 2012]

"Herders are bribed with cash, and our land is torn up by machines," the trio, who go by the English name Poorman, rap in their track "Tears". "Brothers and sisters, we need to wake up!" Once an economic backwater, the development of thousands of coal mines to tap Inner Mongolia's vast mineral reserves has made the region one of China's fastest-growing. But while some have prospered from the mining boom, other Mongolians resent being displaced from their land to make room for the mines, which they say scar the steppe and discriminate against them in recruiting. "There are all these songs about the beauty of Inner Mongolia's grasslands, but when people come to visit they realise it's being turned into desert," said band member Sodmuren, 25, who like many Mongolians uses a single name.

The region's rappers adopted the genre a decade ago from their ethnic fellows in neighbouring Mongolia, an independent country which has had a thriving hip hop scene for more 20 years. "Hip hop is the most honest kind of music there is," Sodmuren told AFP in a recording studio in Inner Mongolia's capital, Hohhot, where swathes of newly built concrete apartment blocks stretch into the grassy countryside.

See Separate Article MONGOLIAN HIP HOP, ROCK POP MUSIC AND DANCE factsanddetails.com

Uighur Hip-Hop

Chris Walker and Morgan Hartley wrote in The Atlantic, “In Urumqi’s poorest districts, some Uighur youth have turned to a non-traditional outlet for maintaining cultural pride: hip-hop. Since 2006, this home-grown rap and dance scene has drawn together thousands of Uighur fans across Xinjiang, and has even managed a feat the founders didn’t expect to achieve: attracting Han Chinese fans. Ekrem, aka Zanjir, was the first Uighur rapper and a co-founder of Six City, Urumqi’s most popular rap collective, for which he now serves as producer and business manager. It’s a part-time gig. In his spare time, he moonlights as a software developer, while other members of the collective drive hospital shuttles or work in traditional Uighur dance shows to make ends meet. [Source: Chris Walker and Morgan Hartley, The Atlantic, October 29, 2013]

“In a simple basement studio wedged between tire stores in a Tianshan strip mall, Ekrem and three other Six City MCs crammed around a computer and a single microphone. On a shelf was a stack of records from their idols — American hip-hop stars like Snoop, Eminem, Ice Cube, and 50 Cent. The men would have fit comfortably in urban America: Ekrem wore a black Dodgers cap, while Behtiyar, a fellow member, had slick-backed hair and wings tattooed on his forearms. Eager to show off, one rapper called “MC-5" started to freestyle.

“He was good. Rap in Uighur is fluid and quick, and the vowels come in rapid succession, from the back of the mouth, producing a smooth sound. “Uighur is much better for rap than Mandarin,” Behtiyar explained. “Uighur is phonetic, like English, so it’s easy to make dope rhymes.” By contrast, he said, it is more difficult to sing in Mandarin.

“But even Six City writes half of their lyrics in Chinese. Their reasoning for this is purely pragmatic. According to Ekrem, it makes Six City’s music more accessible to the mass market of Mandarin speakers. “And the Chinese Government censors less when you mix in Chinese lyrics” he said, with a smile. The collective has had to adapt to government pressure in other ways. “There’s a lot of lyrics we can’t express, so we have to be smart” Behtiyar said. Six City steers clear of politics and discrimination, and instead focuses their songs on Uighur pride or problems of drug and gambling addictions in Urumqi’s low-income neighborhoods. It’s an important way to raise awareness about the culture, and “show China that we’re not a bunch of primitives” says Ekrem, referring to a frequent Han stereotype of Uighurs.

See Separate Article UYGHUR CULTURE. LITERATURE, KNIVES AND HIP HOP factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Fan, artist and Chinese rock websites and blogs ; Asia Obscura; YouTube

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021