EARLY CHINESE POTTERY

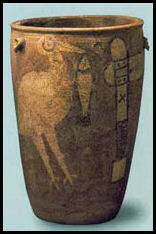

Yangshou vessel, 3300 B.C.Art from the three ancient dynasties---Hsia (2000-1600 B.C.), Shang Dynasty (1766-1122 B.C.) and Zhou Dynasty (1122-221 B.C)---inlcude bronzes, jades, ceramics and textiles with a variety of designs. Some of the earliest art in China features images of dragons and antlered snakes.

The earliest examples of clay pottery found in China date back to 6000 B.C. These clay vessels’some of them with painted flowers, fish, human faces, vaginas and geometric designs---were created by the "Yangshao Culture," (named after village near the confluence of the Yellow, Fen and Wei rivers where the artifacts were found).

Beginning around 3500 B.C., the Lungshnanoid Culture (named after a village in Shandong province where the artifacts were found) produced white pottery and "eggshell-thin" black pottery. Multi-colored and burnished black pottery appeared in Neolithic times in settlements along the upper, middle and lower reaches of the Yellow and Yangtze River.

Advancement in firing techniques lead to new types of pottery such as high-fired stoneware and glazed stoneware developed during the Shang (1766-1122 B.C.), Zhou (1122-221 B.C.), Qin (221-206 B.C.) and Han (206 B.C.” A.D. 220) dynasties.

Good Websites and Sources on Chinese Art: China --Art History Resources art-and-archaeology.com ; Art History Resources on the Web witcombe.sbc.edu ; ;Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) Visual Arts/mclc.osu.edu ; Asian Art.com asianart.com ; China Online Museum chinaonlinemuseum.com ; Qing Art learn.columbia.edu Museums with First Rate Collections of Chinese Art National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw ; Beijing Palace Museum dpm.org.cn ;Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org ; Sackler Museum in Washington asia.si.edu/collections ; Shanghai Museum shanghaimuseum.net

Chinese Painting: University of Washington depts.washington.edu ; Calligraphy : University of Washington depts.washington.edu ; Calligraphy Masters on China Online Museum chinaonlinemuseum.com ; Ceramics : 1) China Museums Online: chinaonlinemuseum.com ; 2) Guide to Chinese Ceramics: Song Dynasty, Minneapolis Institute of Arts; artsmia.org features many examples of different types of ceramic ware produced during the Song dynasty, including ding, qingbai, longquan, jun, guan and cizhou. 3) Making a Cizhou Vessel Princeton University Art Museum artmuseum.princeton.edu. This interactive site shows users seven steps used to create Song- and Yuan-era Cizhou vessels. Crafts : Kites travelchinaguide.com ; Furniture chinatownconnection.com ; Furniture chinese-furniture.com ; Jade: Chinatown Connection chinatownconnection.com ; International Colored Gem Association gemstone.org; Book: “Jade and You” by John Ng.

Early Buddhist Art: Mogao Caves : UNESCO World Heritage Site site: UNESCO ; Digital Dunhuang e-dunhuang.com; Dunhuang Academy, public.dha.ac.cn Longmen Caves: World Heritage Site Sites UNESCO ; UNESCO World Heritage Site List World Heritage Site ; Yungang Grottoes UNESCO World Heritage Site UNESCO

Chinese Culture: China Culture.org chinaculture.org ; China Culture Online chinesecultureonline.com ;Chinatown Connection chinatownconnection.com ; Transnational China Culture Project ruf.rice.edu Book: “The Culture and Civilization”, a massive multi-volume series on Chinese culture (Yale University Press).

Links in this Website: EARLY CHINESE ART Factsanddetails.com/China ; CHINESE ART FROM THE GREAT DYNASTIES Factsanddetails.com/China ; SHANG DYNASTY (2200-1700 B.C.) AND XIA DYNASTY Factsanddetails.com/China ; ZHOU (CHOU) DYNASTY (1100-221 B.C.) Factsanddetails.com/China ; HAN DYNASTY (206 B.C.-A.D. 220) Factsanddetails.com/China ; TANG DYNASTY (A.D. 690-907) Factsanddetails.com/China ; CHINESE JADE Factsanddetails.com/China ; CHINESE CERAMICS AND PORCELAIN Factsanddetails.com/China ; CHINESE PAINTING Factsanddetails.com/China ;CHINESE CALLIGRAPHY Factsanddetails.com/China ; CHINESE CRAFTS Factsanddetails.com/China ; MODERN ART IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; MODERN CHINESE ARTISTS Factsanddetails.com/China ; COLLECTING, LOOTING AND COPYING ART IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Jade: “Jade and You” by John Ng Amazon.com ; “A Companion to Chinese Archaeology” by Anne P. Underhill Amazon.com; “Hongshan Jade: The oldest, most imaginative jades full of mysterious beauty” Kako Crisci Amazon.com ; “Qijia (Jades of the Qijia and related northwestern cultures of early China, ca. 2100-1600 BCE” by Dr. Elizabeth Childs-Johnson and Gu Fang Amazon.com; Ancient Chinese Jade Collection: Chinese Edition. by Henry Liaw and C.F. Zhou Amazon.com ; Bronzes: “Chinese Bronzes” by Christian Deydier Amazon.com; “Chinese Bronze Ware” by Li Song Amazon.com; “A Source Book of Ancient Chinese Bronze Inscriptions” by Constance A Cook (Editor), R Goldin Paul (Editor) Amazon.com ; Art: “The Arts of China” by Michael Sullivan and Shelagh Vainker Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery” by Patricia Bjaaland Welch Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: (World of Art) by Mary Tregear Amazon.com; “Art in China (Oxford History of Art) by Craig Clunas Amazon.com; “Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei” by Wen C. Fong, and James C. Y. Watt Amazon.com ; “The British Museum Book of Chinese Art” by Jessica Rawson, et al Amazon.com ;

China’s Oldest Artworks

Lid from a 4,000-year-old Yangshou pot Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: A tiny 13,500-year-old sculpture crafted from burned bone discovered at the open-air Lingjing site can now lay claim to being the earliest three-dimensional object of art found in East Asia. But what makes something a work of art or someone an artist? “This depends on the concept of art we embrace,” says archaeologist Francesco d’Errico of the University of Bordeaux. “If a carved object can be perceived as beautiful or recognized as the product of high-quality craftsmanship, then the person who produced the figurine should be seen as an accomplished artist.” [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2021]

Measuring only half an inch high, three-quarters of an inch long, and just two-tenths of an inch thick, the bird, a member of the order Passeriformes, or songbirds, was made using six different carving techniques. “We were surprised by how the artist chose the right technique to carve each part and the way in which he or she combined them to achieve their desired goal,” says d’Errico. “This clearly shows repeated observation and long-term apprenticeship with a senior craftsperson.” The artist’s attention to detail was so fine, adds d’Errico, that after finding that the bird was not standing properly, he or she very slightly planed the pedestal to ensure the avian would remain upright.

A painted banner found in the Tomb of the Marquess of Dai, Mawangdui, dated to 160 B.C., is considered the oldest portrait in Chinese history.Madeleine Boucher wrote in the Art Genome Project: “In the early 1970s, archaeologists digging at an ancient grave site in modern-day Hunan province discovered one of the richest treasure-troves of modern history: the tomb of noblewoman Lady Dai, including the perfectly preserved body of the lady herself. The painted silk funeral banner, which lay on the innermost of her nested coffins, contains what is considered to be the earliest portrait in Chinese history. The map-like composition is divided into three spaces: the underworld, the world of the living, and a heaven-like world of the immortals. At center, Lady Dai stands surrounded by family members and attendants, while below relatives give Lady Dai her funeral feast and offer sacrifices to help her soul find the realm of the immortals. This underworld of the tomb, symbolized by giant serpents, is where her body soul (corporeal soul) dwells while her spirit soul ascends to the realm of the immortals above. The insight the banner provides into how the afterlife was structured in early Chinese beliefs makes it as valuable to history as it is beautiful. [Source: Madeleine Boucher, the Art Genome Project, June 24, 2014]

Early Chinese Ceramics

Chinese ceramics is famous for its exquisite forms, shapes, finishes and delicate use of color. Early in China’s history it was raised above utilitarianism to a fine art. Great works of art were patronized by the imperial court and the upper classes and sought after outside of China in Europe and other places.

A fine white pottery was made during the Shang Dynasty. Many vessels were similar in size and shape to bronze vessels made during the same period. Scholars believe the bronze vessels were likely copies of ceramic vessels.

Many great works of pottery and ceramic art came from the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.” A.D. 220). Lovely vessels and objects were buried with dead and have been excavated by archeologists and looters. The first use of glazes on Chinese pottery dates back to this period. Beautiful figures, particularly of animals, were created during Six Dynasties period (A.D. 220-587).

See Separate Articles: CHINESE CERAMICS factsanddetails.com PORCELAIN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CELADONS factsanddetails.com ; JIANGDEZHEN AND ITS PORCELAIN, KILNS AND GLAZING AND PAINTING TECNIQUES factsanddetails.com ; HAN DYNASTY ART: BRONZE MIRRORS, JADE SUITS AND TOMB FIGURES factsanddetails.com TANG HORSES AND TANG ERA SCULPTURE AND CERAMICS factsanddetails.com ;

Neolithic Chinese Jade Pieces and Circular Jades

Liang-gu culture jade tablet,

3300 2000 BC In the Neolithic period (5000-2000 B.C.), priests and military men used jade pieces in the worship of deities and ancestors. The most common ornaments---round pi discs and square ts'ung tubes---symbolized the round heaven and the square earth. Jade ornaments in ancient China were used as authority objects and emblems of power.

Ancient Chinese believed that their ancestors originated with God and communicated through supernatural beings and symbols, whose images were placed on jade ornaments. Ancient shaman most likely used jade ornaments with divine markings to command mystical forces and communicate with gods and ancestors. Jade was also used in ancient burial ceremonies.

In ancient times jade was wedged or cracked from a stone and most likely shaped by artisans using grind stones. Metal tools had not yet been invented. It took a considerable amount of time to shape, polish and engrave the elaborate pieces displayed in museums. Most are though to have been created for royalty or nobility.

Circular jades were fairly common in the Neolithic period. Although they were usually discs with a hole in the middle there were pronounced regional differences. Northern jades from the Hongshan culture (4000-3000 B.C) were transparent green in color, thin on the outer and inner edges, and decorated with images of interlocking clouds and linked circular shapes. Northern jades pieces were mainly worn as ornaments.

Southern circular jades from the lower-Yangtze Liang-chu culture (3200-2300 B.C.) were mostly green and often dotted with white spots. Used primarily as ritual objects, these circular jades were about 20 centimeters in diameter with a central hole drilled from both sides. Raised edges lined the central hole, while the outer edges were flat and circular. The small arc-curves sometimes seen on the surface are remnants of the cutting and carving process.

Southern circular jades from the lower-Yangtze Liang-chu culture (3200-2300 B.C.) were mostly green and often dotted with white spots. Used primarily as ritual objects, these circular jades were about 20 centimeters in diameter with a central hole drilled from both sides. Raised edges lined the central hole, while the outer edges were flat and circular. The small arc-curves sometimes seen on the surface are remnants of the cutting and carving process.

Northwestern circular jades from the Lungshan culture (2500-2000 B.C.) and Shensi and Kansu Qichian culture (2000-1600 B.C.) have a surface with straight lines and a central hole drilled from one side with an angled wall and an upper rim larger than the lower rim. Eastern jades from the lower Yellow River Ta-wen-kou culture (4300-2300 B.C.) were mostly small sized objects influenced by northern and southern styles.

See Separate Articles: JADE AND CHINA: OBJECTS, SOURCES, MINING, ARTISTRY AND SPIRITUALITY factsanddetails.com JADE: SOURCES, MINERAL COMPOSITION, COLOR AND BUSINESS factsanddetails.com ; EARLY CHINESE JADE CIVILIZATIONS factsanddetails.com ; HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JADE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Shang and Zhou Circular Jades

Shang Dynasty (1700-1100 B.C.) circular jades are generally similar to northwestern circular jades. Later Shang pieces featured raised inner rims and thin outer edges, sets of carved concentric circles and images of curling dragons, fish, tigers and birds. During the Zhou Dynasty (1100-221 B.C.) jade pendants were very popular and the level of their craftsmanship was unmatched in any future period.

During the Shang and Zhou dynasties jade objects were important objects in ceremonies and rituals. In the Western Zhou period (1100-700 B.C.) the type and number of circular jades used in ceremonies represented a person's social status. Circular jades from this period were often cut into symmetrical pieces to form sets of two or three pieces.

Circular jades made during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States period (722-221 B.C.) were smaller than those from the Shang and early Zhou periods. They contained carved images of curling chih dragons, grain seeds, and cloud patterns. During this period circular jades were commonly worn by people. Materials other than jade, such as agate and glass were used to make "jade" ornaments.

Jade Suits and Pieces from Han Dynasties

During the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-220 A.D.), the imperial family held jade in great esteem. While alive they wore jade pendants and ingested jade powder. When they died were covered and stuffed with jade. Banners and tomb tiles were imprinted the round pi disk, which was believed to assist the deceased reach the next world quicker.

In the Han period, jade objects were believed to possess auspicious meaning, their uses and functions multiplied. Circular jades---often containing images of twin-bodied animals, mask patterns, grain seeds, rush mat designs, curling chih dragons, and round tipped nipples---decorate buildings. Engraved dragon and phoenix patterns were popular in the Han imperial court.

The greatest expressions of the quest for immortality were the jade suits that appeared around the 2nd century B.C. About 40 of these jade suits have been unearthed. The jade suit of the 2nd century B.C. Prince Liu Sheng unearthed near Chengdu, Sichuan province was made of 2,498 jade plates sewn together with silk and gold wire. Liu Shen was buried with his consort who was equally well clad in a jade suit. Sufficient room was made for the prince's pot belly.

Jade suits were believed to slow decomposition and effectively preserve the body after death. A jade suit unearth in Jiangxi Province was made of roughly 4,000 translucent pieces of jade held together with gold wire. Designed to form fit and cover the body, it has the shape of a robot from a 1950s B science fiction movie.

Jade suit of Liu Sheng 113 B.C.

Chinese Ritual Bronzes

Some of the oldest works of art from China are bronze vessels. The oldest ones date back to the Xia dynasty (2200 to 1766 B.C), when the legendary Yellow Emperor is said to have cast nine bronze tripods to symbolize the nine provinces in his empire.

Most ritual bronze vessels date back to the Shang Dynasty and the Zhou Dynasty (1122-221 B.C). These bronze vessels included elaborately-decorated caldrons, wine jars and water vessels that were used to offer food and drink to spirits, gods and deceased ancestors in political and spiritual ceremonies and rituals. Shang ritual vessels including ding caldrons, used to ritually prepare food for royal ancestors; Lei, large elaborately decorated vessels used to store wine; and yu basins, which may have been used to boil water or steam food.

Bronze vessels symbolized rank and often contained references to ancient imperial ethos, culture and music. One of the National Palace Museum's most prized bronze pieces is a yu wine container from the 11th century B.C. Another beautiful bronze piece is an 8th century B.C. water vessel, used for ritual offerings, with animal-shaped handles and legs in the form of human figures. Scholars believe the bronze vessels were likely copies of ceramic vessels. A fine white pottery was made during the Shang Dynasty. Many ceramic vessels were similar in size and shape to bronze vessels made during the same period.

Bronze vessels often bore inscriptions that said “This container has been made to commemorate--- so and so and were often given as presents to officials from leaders as rewards. Many ancient bronzes were removed from China, especially in the early 20th century, and few have been given back or carefully studied.

Bronze vessels and figures were generally made using the lost wax casting technique, which worked as follows: 1) A form was made of wax molded around a piece of clay. 2) The form was enclosed in a clay mold with pins used to stabilize the form. 3) The mold was fired in a kiln. The mold hardened into a ceramic and the wax burned and melted leaving behind a cavity in the shape of the original form. 4) Metal was poured into the cavity of the mold. A metal sculpture was created and removed by breaking the clay when it was sufficiently cool.

See Separate Articles: BRONZE ART IN ANCIENT CHINA: RITUAL VESSELS AND HOW THEY WERE CAST factsanddetails.com XIA DYNASTY (2200-1700 B.C.): factsanddetails.com ; SHANG DYNASTY ART, BRONZE, JADE AND TECHNOLOGY factsanddetails.com ; ZHOU DYNASTY (1046-256 B.C) ART: BRONZE, JADE AND LACQUER factsanddetails.com ; HAN DYNASTY ART: BRONZE MIRRORS, JADE SUITS AND TOMB FIGURES factsanddetails.com

Shang Bronze Decorations and Figures

Shang ritual bronze

Most Shang vessels were decorated with taotie, face-like symbols with “eyes” composed of swirling lines. These designs have been used by archeologists to determine the spread of Shang culture. At the bottom of one yu basin is an arrangement of flower stems encircled by dragon heads with holes from which steam escaped from the vessel.

Three-legged bronze vessels from the 12th century B.C. contain images of bears, wolves and tigers. Soldiers from this period wore bronze chest plates engraved with attacking leopards with huge claws, birds with wolf ears and eagle beaks, hawks grabbing bear cubs, tigers leaping on antelopes, and dragons

Other interesting bronze art from the Shang Dynasty includes bronze masks that look like bizarre Halloween masks and may have been used by shamans; and a slender nine-foot-high-tall figure with stylized shamanist-style head and enormous hands that once held an elephant tusk.

Shang bronzes fetch high prices at international art auctions and are sought after by looters. A 12th century B.C. Shang owl was sold for around $3 million at an auction in 2000.

Ancient Chinese Sculpture

According to the Shanghai Museum: Chinese sculpture can be traced back to prehistoric stone carving and pottery making. Carvings we might describe as sculpture were produced in large numbers in the Shang and Zhou periods (18th- 3rd century B.C.), but figural sculpture became an important art form only in the Qin and Han dynasties (221 B.C.-A.D 220). The representative works of this period are terra-cotta warriors from the mausoleum complex of the First Emperor of Qin, stone statues from noble and royal tombs of the Han period, and pottery figures showing scenes of daily life, also for tombs. The pottery figures of the Western Han period (2nd-1st century B.C.) have a simple, idealized beauty; those of the Eastern Han period (1st — 2nd century A.D.) show a more realistic style, with lively facial expressions and gestures. Figures of animals have the same liveliness. [Source: Shanghai Museum]

Figurine Playing Lute dates to the Date: Eastern Han (A.D. 25-220) period and is 76 centimeters tall. “This pottery figurine from Sichuan is red in color due to the local soil. The head and body were molded separately and joined at the neck. Eastern Han pottery figurines always wear a smile, whether figurines playing the zither or the flute, or laboring or cooking. The figurine is simple in shape, retaining the primitive and original features with a rough and heavy feeling. The vivid and lively appearance of the figurine fully reflects the relaxed and pleasant mood and expression of the player who was immersed in the melody.

Two Pottery standing female figures from the Western Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-A.D. 24) show a subtlety and elegance that was characteristic of the period. One figure is making an obeisant gesture by cupping one hand in the other next to long hanging sleeves, looking almost like a bird of paradise during a courtship dance. The other is in the middle of a dancing movement with one hand raised , her long sleeves hanging over her shoulder. The carving is very simple, highlighting the dress and posture of the figures.

Early Chinese Buddhist Art and Sculpture

Beginning in the first century A.D., in the Eastern Han period, Buddhism and Buddhist art came to China from India. Buddhist sculpture developed quickly in China. At first in mimicked styles from India but soon acquired a character of its own. The Northern and Southern Dynasties period (A.D. 221-618) witnessed major developments in Buddhist sculpture, as can be seen today in the cave temples of Dunhuang, Maiji Mountain, Yungang, and Longmen. According to the Shanghai Museum: Though fine Buddhist sculptures of stone and gilt bronze survive from other places as well, these cave temples are particularly important to the history of Chinese sculpture because they were carved over a long period of time, making them a record of the sculptural styles of successive periods. Sculptures made in the time of the Northern Wei dynasty (A.D. 386-535) have a graceful linear style that resulted from combining a traditional Chinese sculptural style with influences from India and Central Asia. In the latter half of the sixth century, however, under the Northern Qi and Sui dynasties. Indian influence receded and a very expressive local style arose. [Source: Shanghai Museum]

Denise Leidy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: ““Buddhism may have been known in China as early as the second century B.C., and centers with foreign monks, who served as teachers and translators, were established in China by the second century A.D. Early representations of Buddhas are sometimes found in tombs dating to the second and third century; however, there is little evidence for widespread production and use of images until the fourth century, when a divided China, particularly the north, was often under the control of non–Han Chinese individuals from Central Asia. In addition to freestanding sculptures, numerous images were also carved in cave-temples at sites such as Dunhuang, Yungang, and Longmen. Also found in India and Central Asia, these man-made cave-temples range from simple chambers to enormous complexes that include living quarters for monks and visitors. [Source:Denise Leidy, Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

relief from Yungang Caves

“The period from the fourth to the tenth century was marked by the development and flowering of Chinese traditions such as Pure Land, which focuses on the Buddha Amitabha and the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, and Chan (or Zen). Pure Land practices stress devotion and faith as a means to enlightenment, while Chan features meditation and mindfulness during daily activities; both traditions are also prevalent in Korea and Japan. In addition, after the eight century, new Indic and Central Asian practices were also found in China. These included devotion to the celestial Buddha Vairocana, new and powerful manifestations of bodhisattvas such as Avalokiteshvara, and the use of cosmic diagrams such as mandalas. Many of these practices (best known today in some Japanese traditions and in Tibet) were intended to protect the nation and offer tangible benefits, such as health and wealth, to the ruling elite. Others involved complex rituals and forms of devotion designed for advanced practitioners.\^/

“Chinese Buddhist sculpture frequently illustrates interchanges between China and other Buddhist centers. Works with powerful physiques and thin clothing derive from Indian prototypes, while sculptures that feature thin bodies with thick clothing evince a Chinese idiom. Many mix these visual traditions. After the eleventh and twelfth centuries, when Buddhism disappeared from India, China and related centers in Korea and Japan, as well as those in the Himalayas, served as focal points for the continuing development of practices and imagery.

See Separate Articles: BUDDHIST ART IN CHINA: PAINTINGS, SCULPTURES AND GIANT STATUES factsanddetails.com ; BUDDHIST CAVE ART IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Mogao Caves

Mogao Grottoes---also known as Thousand Buddha Caves---is a massive group of caves filled with Buddhist statues and imagery that were first used in the A.D. 4th century. Carved into a cliff on the eastern side of Singing Sand Mountain and stretching for more than a mile, the grottoes are one of the largest treasure house of grotto art in China and the world.

Mural of Avolokitesvara at Mogao Caves All together there are 750 caves (492 with art work) on five levels, 45,000 square meters of murals, more than 2000 painted clay figures and five wooden structures. The grottoes contain Buddha statues and lovely paintings of paradise, "asparas" (angels) and the patrons who commissioned the paintings. The oldest cave dates back to the 4th century. The largest cave is 130 feet high. It houses a 100-foot-tall Buddha statue installed during the Tang Dynasty (A.D. 618-906). Many caves are so small they can only can accommodate a few people at a time. The smallest cave is only a foot high.

Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “Within the caves, the monochrome lifelessness of the desert gave way to an exuberance of color and movement. Thousands of Buddhas in every hue radiated across the grotto walls, their robes glinting with imported gold. Apsaras (heavenly nymphs) and celestial musicians floated across the ceilings in gauzy blue gowns of lapis lazuli, almost too delicate to have been painted by human hands. Alongside the airy depictions of nirvana were earthier details familiar to any Silk Road traveler: Central Asian merchants with long noses and floppy hats, wizened Indian monks in white robes, Chinese peasants working the land. In the oldest dated cave, from A.D. 538, are depictions of bandits bandits that had been captured, blinded, and ultimately converted to Buddhism. [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, June 2010]

Carved out between the fourth and 14th centuries, the grottoes, with their paper-thin skin of painted brilliance, have survived the ravages of war and pillage, nature and neglect. Half buried in sand for centuries, this isolated sliver of conglomerate rock is now recognized as one of the greatest repositories of Buddhist art in the world. The caves, however, are more than a monument to faith. Their murals, sculptures, and scrolls also offer an unparalleled glimpse into the multicultural society that thrived for a thousand years along the once mighty corridor between East and West.

See Separate Article MOGAO CAVES: ITS HISTORY AND CAVE ART factsanddetails.com

Ancient Chinese Tomb Art, Sculpture and Mingqi (Burial Figures)

In ancient times people believed that the souls of the dead lived after death in another world, where they needed all the same things that people need when they were alive. Living animals and people were often slaughtered and buried with people of high status. During the Zhou Dynasty (1122-221 B.C), the custom of killing living beings was replaced with practice of burying people with pottery or wooden burial figures.

By the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-220 A.D.), it was common for emperors and other noblemen to decorate their tombs with pottery replicas of warriors, concubines, servants, horses, domestic animals, trees, plants, furniture, models of towers, granaries, mortars and pestles, stoves and toilets, and almost everything found in the real world so the deceased would have everything he needed in the next world.

Heather Colburn Clydesdale wrote: “ Burial figurines of graceful dancers, mystical beasts, and everyday objects reveal both how people in early China approached death and how they lived. Since people viewed the afterlife as an extension of worldly life, these figurines, called mingqi or "spirit utensils," disclose details of routine existence and provide insights into belief systems over a thousand-year period. Mingqi were popularized during the formative Han dynasty (206 B.C.–220 A.D.) and endured through the turbulent Six Dynasties period (221–589) and the later reunification of China in the Sui (589–618) and Tang (618–906) dynasties.[Source: Heather Colburn Clydesdale, Independent Scholar Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

Some extraordinarily beautiful sculptures were found in tombs from the state of Chu, which flourished between the 8th and 3rd centuries B.C. in a remote part of China. The Chu produced stylized lacquered deer antlers and a bronze figure with a bird body and serpentine neck. Chu art has brought attention to the fact that non-mainstream and fringe cultures produce art that was a just as beautiful as the art produced by the main Chinese dynasties.

Mingqi in the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.–220 A.D.)

Manjusri Debates

Vimalakirti at Mogao Caves Heather Colburn Clydesdale wrote: “Earthenware mingqi are today the most visible legacy from the Han dynasty due to their durability and number. Although most mingqi were mass produced using molds, they are remarkably animated. Dogs, their ears perked and noses all but twitching, stand alert. Dancers are frozen in mid-step, the alignment of bodies and sweep of sleeves transcending their suspended state to imply the flow of choreography. Drummers succumb to the rhythm of their instruments, kicking up their toes and laughing with joy. This delightful naturalism was central to the figures' purpose of providing the deceased with entertainment, service, and guardianship. [Source: Heather Colburn Clydesdale, Independent Scholar Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“Meanwhile, mingqi in the form of buildings and tools provided staples and comforts for the deceased in the tomb. Entire farms complete with granaries, wells, and watchtowers were recreated in miniature. Details like wooden brackets and tile roofs were loyally reproduced, as were regional differences in building styles, ranging from tall towers in the north, courtyard structures in the south, and houses perched on stilts in marshy areas. Since most of their above-ground counterparts were made of wood and have long since disintegrated, mingqi preserve information about architecture in Han China.\^/

“Mingqi worked in concert with other tomb objects and architecture to support a larger funerary agenda, the goal of which was to comfort and satisfy the deceased, who was believed to have two souls: the po, which resided underground with the body, and the hun. While the hun could ascend to the skies, funerary rituals sometimes sought to reunite it with the po in the safer realm of the tomb. Here, valuables such as bronzes, lacquers, and silks, frequently decorated with Daoist imagery, surrounded the coffin. Around the turn of the millennium, Han tomb architectural styles morphed from pits into multichambered underground dwellings, often with elaborate carvings and wall paintings. Constructed of brick and featuring vaulted ceilings, these tombs were aligned along north-south axes and tied to above-ground stone shrines. Many shrines in turn were covered with low-relief carvings depicting paradises and stories underscoring Confucian virtues like filial piety and loyalty.\^/

“In the first century A.D., the site of ritual offerings for the deceased transferred from the shrine to the tomb itself, and people erected large stone statuary of officials and animals along a "spirit path" leading up to the tomb mound. The shrines and spirit paths became an important way for the living to proclaim the deceased family member's and their own commitment to Confucian values. Ultimately, funerary objects such as mingqi worked in concert with other funerary objects, tomb architecture, shrines, and spirit-road sculptures to achieve a goal that exceeded the well-being of the family. According to Confucian doctrine, when every person performed their prescribed social role to perfection, the cosmos would achieve harmony. By ensuring the well-being of the dead, the living promoted accord in the celestial realm and in their own terrestrial existence.\^/

Mingqi in the Six Dynasties (221–589)

Heather Colburn Clydesdale wrote: “The symbiotic relationship between individual and state, as well as between life and afterlife, meant that tombs underwent dramatic changes after the Han's central authority weakened and ultimately collapsed in 220 A.D. The period of disunion that followed, known as the Six Dynasties (220–589), saw an immediate reaction against ornate tombs, which were considered emblematic of excesses responsible for the downfall of the Han. Even imperial tombs were spare, reflecting ideology as well as economic realities in unstable times. The overall number of mingqi, as well as their quality, declined in the early Six Dynasties. [Source: Heather Colburn Clydesdale, Independent Scholar Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“In southern China, people turned to Daoism, and mingqi, as well as above-ground sculptures, became ever more infused with animal iconography and energized with dynamic lines. The north of China was eventually united by nomadic Tuoba invaders who founded the Northern Wei dynasty (386–534) and established a measure of stability. Their rule fostered both preservation, seen in Han tomb styles and funerary practices, as well as innovation, seen in new types of mingqi such as human-faced guardian animals called zhenmushou, human guardians, and increasing numbers of pack animals and military figures.\^/

Mingqi in the Sui (589–618) and Tang (618–906) Dynasties

Heather Colburn Clydesdale wrote: “When China was unified again, first briefly under the Sui and then under the long and prosperous Tang, mingqi truly resurged as a part of elaborate tombs. Tang mingqi integrated the guardian figures and pack animals of the Northern and Southern Dynasties, but also incorporated the many international influences that were popular during this time of stability and expansion. As in the Han dynasty, Tang mingqi frequently take the form of musicians, dancers, and servants in clay, but are ornamented with sancai (three-color) glaze, an artistic influence that was transmitted from Central Asia along the Silk Road. Foreigners were also frequently depicted, reflecting a cosmopolitan society that embraced exchanges with other groups and cultures. [Source: Heather Colburn Clydesdale, Independent Scholar, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“As in the Han dynasty, Tang mingqi were part of a complex tomb program, often with stone statuary lining a spirit road. However, their function was firmly rooted in consolidating power in the earthly world. Important funerals were sponsored by the state and were a way for the imperial government to strengthen ties with influential Chinese families and even solidify loyalty with foreign emissaries and the governments they represented. As in the Han dynasty, Tang mingqi and the larger program of funerary practices reflected ties among the living.

See Shang Burial Practices, Han Tombs, Xian, Terra-Cotta Army, Ancient Music

Image Sources: Palace Museum, Taipei; Metropolitan Museum of Art; Ohio State University, Mogao Caves Wiki Commons

Text Sources: Palace Museum, Taipei, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021