CHINESE CALLIGRAPHY

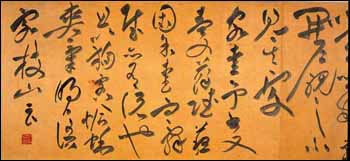

Cursive script

Calligraphy is a system of aesthetic Chinese writing expressed through a variety of brush movements and compositions of dots and strokes. Described as the art of writing and largely unintelligible to Westerners, calligraphy is regarded by Chinese as "the supreme art form” higher than painting and sculpture and more able to express lofty thoughts and feelings than words. Fusing poetry, literature and painting into one art form, calligraphy was considered so important that ancient scholars could not pass their examinations unless they were masters at it. Good calligraphy possesses rhythm, emotion, aesthetic, beauty, spirituality and, perhaps most importantly, the character of the calligrapher. One ancient Chinese historian wrote: "calligraphy is like images without form, music without sound."

Most of works by famous calligraphers displayed in museums come from the eastern Jin dynasty, Tang, Song, Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties. Describing the work of calligrapher Zhao Mengli the New York Times art critic Holland Carter wrote, the script ‘seems to have an aural dimension, like a dramatic reading. So expressive are the linear twists and turns of the brush. The pressure and weights of the ink, the sartorial; punctuations, that you can practically hear his voice.”

From an early age Chinese children are taught that calligraphy and beautiful handwriting are reflections of their character and personality. Rendered in quick fluid strokes calligraphy is more concerned with flow and feeling than skill and precision and is supposed to come straight from the heart. The characters themselves are a kind of poetry. To produce great works calligraphers must tap into the forces of “qi", which Taoists believe permeate nature and the universe.

Water calligraphy is a poetic activity that you can observe in many Chinese parks: Artists use a large brush to write Chinese characters using water instead of ink. Minutes after the characters are written, they disappear. Media Artist Nicholas Hanna built a tricycle that writes Chinese characters on the ground as it moves. [Source: Jeremy Goldkorn, Danwei.com, September 23, 2011]

See Separate Articles: HISTORY OF CHINESE CALLIGRAPHY factsanddetails.com ; TANG AND SONG DYNASTY CALLIGRAPHY factsanddetails.com ; YUAN ART, PAINTING AND CALLIGRAPHY factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PAINTING: THEMES, STYLES, AIMS AND IDEAS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PAINTING FORMATS AND MATERIALS: INK, SEALS, HANDSCROLLS, ALBUM LEAVES AND FANS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE ART: IDEAS, APPROACHES AND SYMBOLS factsanddetails.com ; ART FROM CHINA'S GREAT DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com ;

Websites and Sources on Chinese Painting and Calligraphy: China Online Museum chinaonlinemuseum.com ; Painting, University of Washington depts.washington.edu ; Calligraphy, University of Washington depts.washington.edu ; Websites and Sources on Chinese Art: China -Art History Resources art-and-archaeology.com ; Art History Resources on the Web witcombe.sbc.edu ; ;Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) Visual Arts/mclc.osu.edu ; Asian Art.com asianart.com ; China Online Museum chinaonlinemuseum.com ; Qing Art learn.columbia.edu Museums with First Rate Collections of Chinese Art National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw ; Beijing Palace Museum dpm.org.cn ;Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org ; Sackler Museum in Washington asia.si.edu/collections ; Shanghai Museum shanghaimuseum.net

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Chinese Script: History, Characters, Calligraphy Illustrated Edition” by Thomas O. Höllmann. Maximiliane Donicht Amazon.com; “Masters on Masterpieces of Chinese Calligraphy” by Wen Shi, Zhi Shi, Bian Ji, Bu Bian Amazon.com “Masterpieces of Chinese Calligraphy in the National Palace Museum” by National Palace Museum Amazon.com; Amazon.com; “Chinese Brushwork in Calligraphy and Painting: Its History, Aesthetics, and Techniques” by Kwo Da-Wei Amazon.com; Art; “The Arts of China” by Michael Sullivan and Shelagh Vainker Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery” by Patricia Bjaaland Welch Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: (World of Art) by Mary Tregear Amazon.com; “Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei” by Wen C. Fong, and James C. Y. Watt Amazon.com ; “The British Museum Book of Chinese Art” by Jessica Rawson, et al Amazon.com; “Art in China (Oxford History of Art) by Craig Clunas Amazon.com

Importance of Calligraphy to the Chinese

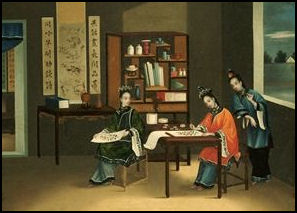

Calligrapher at work

In China, writing is considered the highest art form, and calligraphy is said to be the deepest expression of a person's character. Excelling at calligraphy, was regarded as an important component of being a scholar-gentleman and literati in the imperial period. Not only have professional calligraphers and artists practiced it but also political leaders and other prominent persons are often asked to inscribe their characters on important public events. Good calligraphy is still universally admired. [Source: Stevan Harrell, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia - Eurasia / China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “In China, the style in which an individual writes has long been believed to communicate something essential about his or her personality, intellect, and abilities. Even today it is a common presumption that one can "read" the identity of the person through his or her handwriting. The European term calligraphy means "beautiful writing," and reflects an interest in ornamenting words on the page; most European calligraphy is highly stylized, regular, and decorated with flourishes, which in themselves are lacking in personal expression. Calligraphy in the West was always considered a minor art and tended to curb spontaneity, producing fairly static forms. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

“In China, however, this was far from the case; the most widely practiced writing styles favored spontaneity, and the brush was thought to act like a seismograph in recording the movements of arm, wrist, and hand. East Asian calligraphy was established as a "high art" form well before the Tang dynasty. It has continuously enjoyed a high status among the arts ever since, and is practiced today by many people, including every school-aged child.

Importance of Calligraphy in Chinese Art

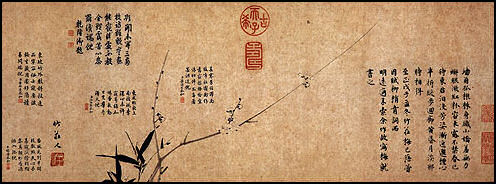

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: Calligraphy, the art of writing, is also one of the most distinctive and highly regarded aesthetic features of Chinese cultural spheres. Written characters in various seal, clerical, cursive, running, and standard script forms not only serve the practical function of conveying information and emotions, they also lend themselves to visual manipulation into aesthetically pleasing forms. In calligraphy and painting, the brush serves as a tool for both, and when painting alone is insufficient to convey ideas, it can also be used to add inscriptions or poetry. In fact, the appearance of poetry as calligraphy on a painting represents these “Three Perfections” combined into a single work. Likewise, painting based on poetry yields great lyrical content without having to add a single character. Thus, the Three Perfections, in addition to the art of seal carving seen as impressions in red, make Chinese painting and calligraphy stand out among art forms in the world in both form and spirit. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei]

Dawn Delbanco of Columbia University wrote: “Calligraphy was the visual art form prized above all others in traditional China. The genres of painting and calligraphy emerged simultaneously, sharing identical tools—namely, brush and ink. Yet calligraphy was revered as a fine art long before painting; indeed, it was not until the Song dynasty, when painting became closely allied with calligraphy in aim, form, and technique, that painting shed its status as mere craft and joined the higher ranks of the fine arts. [Source: Dawn Delbanco, Department of Art History and Archaeology, Columbia University Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“The elevated status of calligraphy reflects the importance of the word in China. This was a culture devoted to the power of the word. From the beginning, emperors asserted their authority for posterity as well as for the present by engraving their own pronouncements on mountain sides and on stone steles erected at outdoor sites. In pre-modern China, scholars, whose main currency was the written word, came to assume the dominant positions in government, society, and culture.\^/

“But in addition to the central role played by the written word in traditional Chinese culture, what makes the written language distinctive is its visual form. Learning how to read and write Chinese is difficult because there is no alphabet or phonetic system. Each written Chinese word is represented by its own unique symbol, a kind of abstract diagram known as a "character," and so each word must be learned separately through a laborious process of writing and rewriting the character till it has been memorized. To read a newspaper requires a knowledge of around 3,000 characters; a well-educated person is familiar with about 5,000 characters; a professor with perhaps 8,000. More than 50,000 characters exist in all, the great majority never to be used.\^/

“Yet the limitation of the written Chinese language is also its strength. Unlike written words formed from alphabets, Chinese characters convey more than phonetic sound or semantic meaning. Traditional writings about calligraphy suggest that written words play multiple roles: not only does a character denote specific meanings, but its very form should reveal itself to be a moral exemplar, as well as a manifestation of the energy of the human body and the vitality of nature itself.\^/

Chinese Calligraphy: Recognized by UNESCO and Bankers

Chinese Calligraphy was inscribed in 2009 on the UNESCO List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. According to UNESCO: Chinese calligraphy has always been more than simply a tool for communication, incorporating as it does the element of artistry for which the practice is still valued in an age of ballpoint pens and computers. Indeed, calligraphy is no longer the basic tool of intellectuals and officials but has become the preserve of professional artisans and amateur enthusiasts. [Source: UNESCO]

Whether they are recording information or simply creating beautiful forms, calligraphers’ brushes are used to ink five different styles of script, known as ‘seal’, ‘official’, ‘cursive’, ‘running’ and ‘regular’. The art may appear on any writing surface — even the rocky walls of cliffs — but it is especially common on letters, scrolls, works of literature and fan coverings. Today, in addition to traditional master-apprentice instruction, calligraphy is also taught at school. Many ceremonies that mark national celebrations and religious rituals incorporate the practice and calligraphy has itself proved influential on modern art, architecture and design. In its distinctive Chinese form, calligraphy offers an important channel for the appreciation of traditional culture and for arts education. It is also a source of pride and pleasure for the Chinese people and embodies important aspects of the country’s intellectual and artistic heritage.

Tang Shuangning, president of EverbrightBank, a fast-growing lender that recently applied for a stock marketlisting, has suggested that managing a bank in China is no more complicated than executing a fine work of calligraphy. “Approaching a piece of white paper to write calligraphy is like mapping out a strategy in China's economy,” Tang told Reuters, “The lines of your writing are where you want to lead the money flow. And it all depends on how you make use of your potential power.” Describing a a meeting of master calligrapher Simon Rabinovitch of Reuters wrote: “In a smoky hotel room in Beijing's old imperial center, he gathered together a small group of top officials and scholars. They talked in hushed tones...the assembled few discussed...Tang's calligraphy, of course. One after the other, over the course of four hours, they admired, praised and critiqued his handiwork, the swirling black brush strokes on white scrolls.” Book: “Brushes with Power” by Richard Curt Kraus is about elite calligraphy

Five Basic Calligraphy Scripts

There are basically five categories of calligraphy: seal, clerical, cursive, standard, and running. All five categories are still used today. Dawn Delbanco of Columbia University wrote: “The Chinese written language began to develop more than 3,000 years ago and eventually evolved into five basic script types, all of which are still in use today. The earliest writing took the form of pictograms and ideographs that were incised onto the surfaces of jades and oracle bones, or cast into the surface of ritual bronze vessels. Then, as the written language began to take standardized form, it evolved into "seal" script, so named because it remained the script type used on personal seals. By the later Han dynasty (2nd century A.D.), a new regularized form of script known as lishu or "clerical" script, used by government clerks, appeared. It was also in the Han that the flexible hair brush came into regular use, its supple tip producing effects, such as the final wavelike diagonal strokes of some characters, that were not attainable in incised characters. [Source: Dawn Delbanco, Department of Art History and Archaeology, Columbia University Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“Increasingly cursive forms of writing, known as "running" script (xingshu) and "cursive" script (caoshu), also developed around this time, both as a natural evolution and a response to the aesthetic potential of brush and ink. In these scripts, individual characters are written in abbreviated form. At their most cursive, two or more characters may be linked together, written in a single flourish of the brush. As the individual brushstrokes of clerical script were inflected with the more fluid and asymmetrical features of cursive script, a final script type, known as "standard" script (kaishu), evolved. In this elegant form of writing, each brushstroke is clearly articulated through a complex series of brush movements. These kinaesthetic brushstrokes are then integrated into a dynamically balanced, self-contained whole.\^/

Over the centuries, calligraphers were free to write in any of the five script styles, depending on the text's function. Beginning by emulating the styles of earlier masters, later writers sought to transform their models to achieve their own personal manner (2000.345.1,2). The calligraphic tradition remains alive today in the work of many contemporary Chinese artists.\^/

Development of the Main Chinese Calligraphy Script Types

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Written records hold a significant place in China's history. The earliest surviving examples, from the Shang capital of Anyang, date to the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries B.C.. These oracle bone records were divination results inscribed on turtle shells and shoulder blades of oxen. Since Shang times Chinese has been written not with an alphabet-based script of the sort we are used to, but one with a symbol ("character") for each word. Many characters are made up of components, some of which can also stand on their own. Often characters can be broken down into two major parts, one which indicates the general meaning of the word, and one which indicates the sound. Each character is formed by a set number of marks, or strokes, made by the brush in a certain order. Simple and complicated characters alike follow the same rules of execution: the order of strokes is completed from left to right and from top to bottom; components that enclose other elements are "closed" after the inner ones are completed. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

“Before the invention of paper, documents were written in vertical columns on strips of bamboo. The strips were then bound together with string. Many different types of regional scripts developed during the Warring States Period as the need for written records increased in state offices that were not centrally controlled. The Qin and Han periods were important for the standardization of script types.

“The seal script, also called smaller seal, is one of the last descendants of the ancient script types used in oracle bone and bronze inscriptions. Clerical script developed from the small seal script in the first century B.C., but its peak period of usage was during the Eastern Han (A.D. 25-220). This script is also referred to by the term "breaking wave," which refers to the outward flaring shape of the right and left downward slanting strokes. (Look for the word that means "big" in the example at left).

“In Chinese writings about calligraphy, much attention is paid to the beginnings and ends of strokes and whether the tip of the brush is visible or not. The expression "hiding the head" refers to the way the calligrapher makes the brush double back on the initial stroke to conceal the entry point where brush first meets paper, while "exposing the tail" refers to the way the calligrapher allows the tip of the brush to show, giving the stroke a pointed end.

“In later periods, cursive script was exploited for its expressive, aesthetic potential. From the fourth century onward, cursive was the vehicle in which a master calligrapher could express his or her individuality. It was also used for personal correspondence and non-official writings. Not everyone was in favor of the abbreviated forms of cursive script; one of the earliest texts about calligraphy still extant from the Han period is a fervent diatribe against the widespread use of draft cursive.

“Regular or standard script was the last of the four major types to develop at the end of the Han dynasty. Execution of regular script involves techniques of brush manipulation that were adapted from the other script types. These include an increase in brush movement, hesitations and changes of brush direction as well as variations in the pressure exerted on the brush tip and the speed with which individual strokes were written. Regular script was considered the most legible and convenient form of handwriting.

Cursive Calligraphy

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Cursive (also known as "grass") script (ts'ao shu) is the most abbreviated and fluid form of Chinese calligraphy. In the third century B.C., the custom of recording private and public items became increasingly common. If documents had continued to be transcribed in the formal and complex seal and clerical scripts, considerable delay would have ensued. Consequently, Chinese writing became increasingly simplified. Characters written quickly were known as draft cursive (chang-ts'ao), which was practiced through the years and matured by the time of the Eastern Han (20-220). The characters in draft cursive appear individually and preserve the upward movement at the tips of the horizontal strokes in clerical script. After eliminating this feature from the brushwork, characters became connected together and the brushstrokes even further abbreviated and spirited, creating what is known as "modern cursive." [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

This form became popular from the Eastern Jin (317-420), and its functional purpose was elevated to an art form by the most representative artists at this early stage; Wang Xizhi (303-361) and Wang Xianzhi (344-388), father and son (also known as the Two Wangs). In the Liang (502-557) and early Tang dynasty (618-907), Wang Xizhi became venerated as the "Sage of Calligraphy." By the High Tang (8th century), modern cursive became freer, developing into what is known as "wild cursive." Chang Hsu (fl. ca. 700-750) was recognized for the great variety in his wild cursive. It is said that when he got drunk, he let the brush fly and ink dance with freedom and abandon, hence his nickname "Madman Chang." Slightly later, the monk Huai-su (725-785) became renowned for his particularly wild and expressive style. "Autobiography," his masterpiece in the National Palace Museum collection, had a great influence on generations of calligraphers to come.

“The Four Masters of the Northern Song (Cai Xiang [1012-1067], Su Shih [1036-1101], Huang Tingjian [1045-1105], and Mi Fu [1051-1107]) all excelled at semi-cursive (hsing-ts'ao) and running (hsing) script. After Huang Tingjian saw Huai-su's "Autobiography" in his later years, his cursive script witnessed a major change as he established a highly personal style of semi-cursive script. In the early Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), calligraphy was influenced by the trend of revivalism. Artists such as Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322) and Hsien-yu Shu (1257-1302) advocated a return to the earlier styles of the Wei and Chin, taking the form practiced in the Chin and Tang dynasties as the standard of aesthetic beauty. The long-neglected form of draft cursive was revived at the time and became popular in the late Yuan and early Ming dynasty (1368-1644).

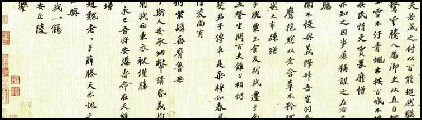

Running Script

According to an exhibition of calligraphy by Dr. Sze Chi-Ching: Running script had already been formed in the late Eastern Han dynasty, reaching its prime in the Eastern Jin dynasty. Its style moderates between regular script and cursive script: it is more free-flowing than the orderly regular script while more easily recognized than the spontaneous cursive script. It was thus widely used. Although running script runs in unrestrained manner, excelling in the writing of this script was not easy. Good practice of regular script is a pre-requisite for fine writing in running script. [Source: Run Run Shaw Library, Chinese Civilization Centre, City University of Hong Kong]

Wang Xizhi is the most representative personae for the prime age of running script. “His Preface to the Orchid Pavilion” has been commonly recognized as the prime running script among all. Running script was also common in the Tang dynasty. Yan’s Lament for a Nephew has been commented on as the piece of running second to the Preface to the Orchid Pavilion. For the calligraphy of the Song dynasty, running script made a great achievement. The four major masters of the Song dynasty: Su Shi (1037-1101), Huang Tingjian, Mi Fu and Cai Xiang (1012-1067) were experts at running script. Among calligraphers of the Yuan dynasty, Zhao Mengfu was expert at running script. Some people say that he embodies the essence of calligraphy of earlier generations, particularly benefiting from the father-and-son of Wang Xizhi, influencing the calligraphy circle of the time. Most calligraphers of Ming dynasty were good at running script, including Wen Zhengming and Dong Qichang. Running script of the Qing dynasty was strongly influenced by Zhao Mengfu and Dong Qichang, producing “pavilion form.” In post-Emperor Qianglong’s time, many steles were unearthed. Since then, calligraphy changed its course, for example, Zheng Xie (1693-1766) built in the component of a seal script in running script and modeled a new style. Liu Yong (1720-1804) modeled after Zhao Mengfu and Dong Qichang in an early stage and immersed himself in stele carving in a later stage.

“Clear Day after Brief Snow Model Calligraphy” is one of the representative pieces of running script by Wang Xizhi. It is a short piece written in running-regular script. In terms of use of the brush, round and circular brush strokes dominate. Sharpness was not evident in the dots, strokes, ticks and hooks. The combination of structures stands firm and balanced. An introverted sense and simplicity is aired in delicate postures. A classical and noble air runs through the entire structure.

Chinese Painting and Calligraphy

In imperial times, painting and calligraphy were the most highly appreciated arts in court circles and were produced almost exclusively by amateurs--aristocrats and scholar-officials--who alone had the leisure to perfect the technique and sensibility necessary for great brushwork. Calligraphy was thought to be the highest and purest form of painting. The implements were the brush pen, made of animal hair, and black inks made from pine soot and animal glue. In ancient times, writing, as well as painting, was done on silk. But after the invention of paper in the first century A.D., silk was gradually replaced by the new and cheaper material. Original writings by famous calligraphers have been greatly valued throughout China's history and are mounted on scrolls and hung on walls in the same way that paintings are. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Painting in the traditional style involves essentially the same techniques as calligraphy and is done with a brush dipped in black or colored ink; oils are not used. As with calligraphy, the most popular materials on which paintings are made are paper and silk. The finished work is then mounted on scrolls, which can be hung or rolled up. Traditional painting also is done in albums and on walls, lacquerwork, and other media. * Maxwell Hearn of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The discipline” of painting this kind of mastery requires derives from the practice of calligraphy. Traditionally, every literate person in China learned as a child to write by copying the standard forms of Chinese ideographs. The student was gradually exposed to different stylistic interpretations of these characters. He copied the great calligraphers' manuscripts, which were often preserved on carved stones so that rubbings could be made. He was also exposed to the way in which the forms of the ideographs had evolved. Over time, the practitioner evolved his own personal style, one that was a distillation and reinterpretation of earlier models. [Source: Maxwell Hearn, Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art \^/]

Chinese ideographs evolved from “their earliest appearance on bronzes, stones, and bones about 1300 B.C. (known today as "seal" script, after its use on the red seals of ownership); their gradual regularization, culminating with the bureaucratic proliferation of documents by government clerks during the second century A.D. ("clerical" script); their artful simplification into abbreviated forms ("running" and "cursive" scripts); and the fusion of these form-types into "standard" script, in which the individually articulated brushstrokes that make up each character are integrated into a dynamically balanced whole...The practice of calligraphy became high art with the innovations of Wang Xizhi in the fourth century.

Beginning in the Tang dynasty (A.D. 618-907), the primary subject matter of painting was the landscape, known as shanshui (mountain-water) painting. In these landscapes, usually monochromatic and sparse, the purpose was not to reproduce exactly the appearance of nature but rather to grasp an emotion or atmosphere so as to catch the "rhythm" of nature. In Song dynasty (960-1279) times, landscapes of more subtle expression appeared; immeasurable distances were conveyed through the use of blurred outlines, mountain contours disappearing into the mist, and impressionistic treatment of natural phenomena. Emphasis was placed on the spiritual qualities of the painting and on the ability of the artist to reveal the inner harmony of man and nature, as perceived according to Taoist and Buddhist concepts. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Beginning in the thirteenth century, there developed a tradition of painting simple subjects--a branch with fruit, a few flowers, or one or two horses. Narrative painting, with a wider color range and a much busier composition than the Song painting, was immensely popular at the time of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). *

During the Ming period, the first books illustrated with colored woodcuts appeared. As the techniques of color printing were perfected, illustrated manuals on the art of painting began to be published. Jieziyuan Huazhuan (Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden), a five-volume work first published in 1679, has been in use as a technical textbook for artists and students ever since. *

Calligraphy and Painting Tools

The tools and brush techniques for painting and calligraphy are virtually the same and calligraphy and painting are often considered sister arts. The traditional tools of the calligrapher and the painter are a brush, ink and an inkstone (used to mix the ink). The Chinese writing brush has a unique structure that allows it to hold ink in a reservoir (the solid black area inside the brush) between layers of animal hairs, which are wrapped successively around a long, central core of bristles. The hairs themselves are highly flexible and responsive to slight changes in pressure and movement of the hand. Chinese calligraphers and painters both used brushes whose unique versatility was the result of a tapered tip, composed of careful groupings of animal hairs. Chinese calligraphers prized bamboo brushes tipped with hair from the thick autumn coats of martens.

Many brushstrokes depict things found in nature such as a "rolling wave," "leaping dragon," "playful butterfly," "dewdrop about to fall," or "startled snake slithering through the grass." Natural terms such as "flesh," "muscle" and "blood" are used to describe the art of calligraphy itself. Blood, for example, is a term used to describe the quality of the ink. Calligrapher’s paper is still made by hand in some places by smoothing oatmeal-like pulp made of inner tree bark and rice and pressing and drying it.

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”, published in in 1894: “The Chinese pride themselves upon being a literary nation, in fact the literary nation of the world. Pens, paper, ink, and ink-slabs are called the"four precious things," and their presence constitutes a “literary apartment." It is remarkable that not one of these four indispensable articles is carried about the person. They are by no means sure to be at hand when wanted, and all four of them are utterly useless without a fifth substance, to wit, water, which is required for rubbing up the ink. The pen cannot be used without considerable previous manipulation to soften its delicate hairs, it is very liable to be injured by inexpert "handling, and lasts but a Comparatively short time. The Chinese have no substitute for the pen, such as lead pencils, nor if they had them, would they be able to keep them in repair, since they have no pen-knives, and no pockets in which to carry them. We have previously endeavoured, in speaking of the economy of the Chinese, to do justice to their great skill in accomplishing excellent results with very inadequate means, but it is not the less true that such labour saving devices as are so constantly met in Western lands, are unknown in China. [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894]

Works of calligraphy and paintings were generally not painted on canvas like Western painting. They appear as murals, wall paintings, album leaf paintings, hanging scrolls and handscrolls. Hanging scrolls are hung on walls as interior adornments; handscrolls are unrolled on table tops; and album leaf paintings are small paintings of various shapes collected in book-like albums with "butterfly mounting," "thatched window mounting" and “accordion mounting."

Painting, Calligraphy and Poetry

Unlike artists in the West who were either skilled craftsmen paid by the hour or professional artists who were commissioned to produce unique works of art, Chinese artists were often amateur scholar gentlemen "following revered ancients in harmony with forces of nature." Calligraphy and painting were seen as scholarly pursuits of the educated classes, and in most cases the great masters of Chinese art distinguished themselves first as government officials, scholars and poets and were usually skilled calligraphers. Sculpture, which involved physical labor and was not a task performed by gentlemen, never was considered a fine art in China.

Poetry is much more fully integrated into painting and calligraphy in Chinese art than it is into painting and writing in Western art. There are two words used to describe what a painter does: “Hua hua" means "to paint a picture" and “xie hua" means "to write a picture." Many artists prefer the latter.

Poetry, painting and calligraphy were known as the "Three Perfections." Poems are often the subjects of painting. Painters were often inspired by poetry and tried to create works with a poetic, lyrical quality.

Recalling a series of twelve poems by Su Shih (1036-1101) that inspired him, the great master painter Shih T'ao (1641-1717) wrote: "This album had been on my desk for a year and never once did I touch it. One day, when a snow storm was blowing outside, I thought of Tung-p'o's poems describing twelve scenes and became so inspired that I took up my brush and started painting each of the scenes in the poems. At the top of each picture I copied the original poem. When I chant them the spirit that gave them life emerges spontaneously from paintings." [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

When a painting did not fully convey the artist feelings, the artist sometimes turned to calligraphy to convey his feelings more deeply. Describing the link between writing and painting, the artist-poet Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322) wrote:

“Do the rocks in flying-white, the trees in ancient seal script

And render bamboo as if writing in clerical characters:

Only if one is truly able to comprehend this, will he realize

That calligraphy and painting are essentially the same.”

Other times the message of the calligraphy was more mundane. An inscription on the side of “Sheep and Goat” by Zhao Mengfu read: "I have painted horses before, but have never painted sheep, so when Zhongxin requested a painting, I playfully drew these for him from life. Though I can not get close to the ancient masters, I have managed somewhat to capture their essential spirit”.

Rubbings and Learning and Transmitting Calligraphy

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Even before printing was invented in China, the Chinese devised other ways of preserving and transmitting texts. Hand copies were indispensable for passing on texts and provided ample opportunity for calligraphy practice. A tracing copy could be made by tracing the outlines of each character onto paper that was specially treated to make it highly transparent; after the outlines were drawn, the characters were inked in. The more skilled calligraphers made free-hand copies, keeping the original close at hand as they wrote. Original calligraphy, even from the most famous hands, often did not survive because of the fragility of the silk or paper it was written on. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington]

“Many of the examples of well-known calligraphers were collected soon after they were written and painstakingly inscribed in stone. Copies of these engravings could then be used as study guides. They were highly valued as being as close to the original ink-on-paper version as it was possible to get. Examples of this are rubbings, which are easy to distinguish from handwritten copies, as the characters in a rubbing appear in white on a black ink background.” To do this”evenly moistened paper is applied to the clean surface of the engraved stone tablet and pushed into the incised areas, first with a brush and then with a mallet and piece of felt. An ink-filled cotton pad is used to daub ink onto the surface of the paper, turning it black where it contacts the uncarved flat surface underneath. When the paper is fully inked and the details of all the brushwork are visible on the surface, the imprint is pulled from the surface of the stone.

To learn calligraphy, students begin by copying the handwriting of famous masters, using copybooks of rubbings or, if possible, original examples. The mature calligrapher, having learned the various styles of many famous calligraphers over decades of study and practice, develops a signature style of his or her own, usually based on or influenced by a calligraphic master of the past.

Ideals and Goals of Chinese Calligraphy

Consider two Tang-dynasty texts that describe calligraphy in human terms, both physical and moral. Here, the properly written character assumes the identity of a Confucian sage, strong in backbone, but spare in flesh: 1) "[A written character should stand] balanced on all four sides . . . Leaning or standing upright like a proper gentleman, the upper half [of the character] sits comfortably, while the bottom half supports it." (From an anonymous essay, Tang dynasty). 2) "Calligraphy by those good in brush strength has much bone; that by those not good in brush strength has much flesh. Calligraphy that has much bone but slight flesh is called sinew-writing; that with much flesh but slight bone is called ink-pig. Calligraphy with much strength and rich in sinew is of sagelike quality; that with neither strength nor sinew is sick. Every writer proceeds in accordance with the manifestation of his digestion and respiration of energy." (From Bizhentu, 7th century). [Source: Dawn Delbanco, Department of Art History and Archaeology, Columbia University Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

Other writings on calligraphy use nature metaphors to express the sense of wonder, the elemental power, conveyed by written words: 1) "[When viewing calligraphy,] I have seen the wonder of a drop of dew glistening from a dangling needle, a shower of rock hailing down in a raging thunder, a flock of geese gliding [in the sky], frantic beasts stampeding in terror, a phoenix dancing, a startled snake slithering away in fright. (Sun Guoting, 7th century). 2) A dragon leaping at the Gate of Heaven. (Description of the calligraphy of Wang Xizhi by Emperor Wu [r. 502-49]). \^/

And so, despite its abstract appearance, calligraphy is not an abstract form. Chinese characters are dynamic, closely bound to the forces of nature and the kinesthetic energies of the human body. But these energies are contained within a balanced framework—supported by a strong skeletal structure—whose equilibrium suggests moral rectitude, indeed, that of the writer himself.\^/

Beauty, Control and Morality of Calligraphy

From their inception there has been a link between Chinese writing and art that does not have a counterpart in the West. Calligraphy has given Chinese poems, essays, letters and even official government documents a beauty that transcends the contents of what was written. There is no fixed relationship between the written Chinese language and the aesthetic beauty of calligraphy, but what is written with calligraphy does have meaning---and this relationship between the aesthetics of writing and meaning of the words is unique to Chinese calligraphy.

Standard (regular) script

The beauty of calligraphy is often described with imagery from nature. Sun Kuo-t'ing wrote in the “Manual of Calligraphy”, calligraphy can be "heavy like piled-up clouds, light like the wings of a cicada." If one leaves the writing alone "it flows like a stream, stop it and a mountain sits in majestic serenity." Sun Kuo-t'ing also compared calligraphy to human images calling it “a lovely maiden adorning her hair with flowers," with "full veins and flesh brimming with beauty."

Some have compared calligraphy to music in terms of the speed and rhythms of the movements and the fluidity of the characters. Zong Baihua wrote in “Aesthetics of Chinese Calligraphy”: "Variations in density of composition, light and heavy strokes, slow and fast brushwork all affect form and content. It is like picking out notes from the myriad sounds of nature in musical or artistic creations, developing laws of combining those notes, and using variations in volume, pitch, rhythm, and melody to express images in nature and society and the feelings in one's heart."

As is true with painting, one of the goals of calligraphy is to develop a calm mind, a cultivated memory. The characters, like objects of a painting, express reverence for nature and project a metaphor for the nobility of man.

Dawn Delbanco of Columbia University wrote: ““Expressive as calligraphy is, it is also an art of control. A counterbalance of order and dynamism is manifested in all aspects of Chinese writing. In traditional Chinese texts, words are arranged in vertical columns that are read from right to left. Traditional texts have no punctuation; nor are proper nouns visually distinguishable from other words. The orderly arrangement of characters is inherent in each individual character as well. One does not write characters in haphazard fashion: an established stroke order ensures that a character is written exactly the same way each time. This not only makes the formidable task of memorization easier, but ensures that each character will be written with a sense of balance and proportion, and that one is able to write with an uninterrupted flow and rhythm. The calligrapher and the dancer have much in common: each must learn choreographed movements; each must maintain compositional order. But once the rules have been observed, each may break free within certain boundaries to express a personal vitality. [Source: Dawn Delbanco, Department of Art History and Archaeology, Columbia University Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

Brushwork in Chinese Calligraphy

Dawn Delbanco of Columbia University wrote: “How can a simple character convey” so much? “The use of brush and ink has much to do with it. The seeming simplicity of the tools is belied by the complexity of effects. A multiplicity of effect is produced in part by varying the consistency and amount of ink carried by the brush. Black ink is formed into solid sticks or cakes that are ground in water on a stone surface to produce a liquid. The calligrapher can control the thickness of the ink by varying both the amount of water and the solid ink that is ground. Once he starts writing, by loading the brush sometimes with more ink, sometimes with less, by allowing the ink to almost run out before dipping the brush in the ink again, he creates characters that resemble a shower of rock here, the wonder of a drop of dew there. [Source: Dawn Delbanco, Department of Art History and Archaeology, Columbia University Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

Plum and Bamboo by Wu Zhen

The brush, above all, contributes to the myriad possibilities. Unlike a rigid instrument such as a stylus or a ballpoint pen, a flexible hair brush allows not only for variations in the width of strokes, but, depending on whether one uses the tip or side of the brush, one can create either two-dimensional or three-dimensional effects. And depending on the speed with which one wields the brush and the amount of pressure exerted on the writing surface, one can create a great variety of effects: rapid strokes bring a leaping dragon to life; deliberate strokes convey the upright posture of a proper gentleman.\^/

The brush becomes an extension of the writer's arm, indeed, his entire body. But the physical gestures produced by the wielding of the brush reveal much more than physical motion; they reveal much of the writer himself-his impulsiveness, restraint, elegance, rebelliousness Abstract as it appears, calligraphy more readily conveys emotion and something of the individual artist than all the other Chinese visual arts except for landscape painting, which became closely allied with calligraphy. It is no wonder that twentieth-century American Abstract Expressionists felt a kinship to Chinese calligraphers.\^/

Fan Calligraphy

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Fans were a common means of cooling off in the past, and their surfaces were often decorated with painting and/or calligraphy, becoming one of the unique art formats for painting in ancient China. As part of the social interaction among Chinese scholars was the reciprocal giving of fans as well as cooperative production of painting and calligraphy on their surfaces, fans became an intricate part of the elegant pastimes in scholarly life. In earlier periods, painters and calligraphers mainly used the silk surface of round fans, but by the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), after the folding fan became popular, the paper surface of this format became an alternative for painting and calligraphy. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“The folding fan, when extended, forms an arched shape. As the name suggests, it can be folded into a compact form. Said to have originally derived from tribute gifts sent from Korea and Japan, it became popular in China at least by the Northern Song period (960-1126). Even then, one can find precedents of fan surfaces decorated with painting and calligraphy. Becoming a favorite medium for scholar painters and calligraphers wielding the brush, this art form flourished approximately in the period of the Four Great Masters of the Ming dynasty — Shen Chou, Wen Cheng-ming, Tang Yin, and Qiu Ying, who helped foster the trend of painting and calligraphy on folding fans. In the Ming dynasty, there were even shops that produced folding fans and specially made fan paper for sale. Without the slats inserted between the front and back pieces of paper, it made them convenient for writing and mounting, hence the name “surfaces of convenience”. Mounting into the album leaf format allows them also to be conveniently collected and appreciated as well.

“Round fans (known in Chinese as “wan-shan” or “t’uan-shan”) are not usually circular in form, but actually more squarish with rounded corners. With short handles, they were often used in the palaces of ancient times and hence known as “palace fans”. Round fans also have a uniquely decorative function, in which various grades of silk textile were specifically chosen and then adorned with calligraphed poetry or a small painting to enhance their aesthetic quality.

Record Prices for Traditional Chinese Art and Calligraphy in 2010

At the 2010, spring sales draw a number of ancient Chinese paintings and calligraphy works were sold for record prices. Several pieces fetched more than 100 million yuan ($18 million) each at sales hosted by domestic auction giants Beijing Poly, China Guardian and Beijing Hanhai, with one reaching 436.8 million yuan ($63.8 million). Apart from the astronomically-high sales, a large number of works went for around the 20-million-yuan ($2.94 million) mark. [Source: Wu Ziru, Global Times, June 2, 2010]

“This is an all-ascending market that you could have hardly imagined before,” Zhao Li, professor at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, told the Global Times. “Collectors and investors just keep bidding, as long as there is a rare piece.” “It used to be beyond our imagination that a piece of Chinese work, no matter how precious it is, could be sold for hundreds of millions of yuan,” commented Hu Jiaojiao, vice director of China Guardian. “Things are changing so fast today. Now we are confident that the market is sound and healthy, with so many collectors interested in classic paintings and calligraphic works.”

Hand scroll Dizhuming by poet and calligrapher Huang Tingjian from the Song Dynasty (960-1279) was one of the most hotly pursued items. It finally sold for 436.8 million yuan at Poly's spring sales to an undisclosed buyer, the price far beyond the expectations from both the auction house and collectors alike.

The sale set a new record for any genre of Chinese work - from antiques to contemporary pieces, almost doubling the previous high of 230 million yuan ($34 million) for a piece of blue and white porcelain from the Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368), which sold at Christie's in London five years ago.

The 15-meter-long calligraphic hand scroll, Dizhuming, was completed in 1095. The original length of the hand scroll was 8.24 meters, but was then extended to 15 meters over the span of 800 years as its collectors, including prominent ancient Chinese scholars and royal court officials, added additional inscriptions to the piece.

Six Chinese classic paintings and calligraphic works each selling for over 100 million yuan. Temple in Mountains in Autumn, a landscape painting by Yuan Dynasty artist Wang Meng was sold for 136.64 million yuan ($20.1 million). Hand scroll painting Mount Yandang by Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) painter Qian Weicheng went under the hammer for 129.92 million yuan ($20 million), five times its former record price of 24.08 million yuan ($3.5 million) at China Guardian's 2007 spring auctions.

Not only people from auction houses, but also many experts see the record-breaking prices as a good thing for the Chinese art market, saying there is still a large gap to be filled in terms of catching up with the international scene.

More and more wealthy people are turning to buying artwork as they think about how to spend their money, according to art market expert Zhao Li. “Ancient Chinese works are their favorite because of their scarcity, plus, the value would be steady compared with contemporary ones.”

Image Sources: 1,8) Palace Museum Taipei; 2) All Posters.com, Search Chinese Art; 3, 5) Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html ; 4) University of Washington; 6, 7) Metropolitan Museum of Art

Text Sources: Palace Museum, Taipei, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021