AI WEI WEI

Ai Weiwei is an internationally known sculptor, filmmaker, architect and performance artist. The son of one China’s greatest modern artists and poets, Ai Qing, Ai Weiwei is regarded as a conceptualist who specializes in works that stir up controversy and confronts viewers and authorities. He has disassembled antique furniture to make them unusable and had himself photographed destroying a 2000-year-old Han Dynasty vase. On the fifth anniversary of Tiananmen Square he photographed a young woman standing in front of the Mao portrait on the square, provocatively slipping up her skirt. That young woman was his wife, the artist Lu Qing.

Ai was leader in the revolutionary Stars Group of the late 1970s and the idea man behind the iconic Bird's Nest Olympic stadium. He helped design the stadium for the 2008 Olympics, then renounced his role after concluding that Chinese leaders had politicized the games. His blog is visited by 10,000 people a day and his architectural firm, Fake Design, is working on 50 projects. Over $4 million was spent on a performance piece in which 1,001 Chinese citizens were placed in the middle of Kassel, Germany, all wearing clothes deigned by Ai.

Ai Wei Wei was described by The New Yorker as a “fitfully, brilliant conceptualist in many mediums." He is known for creating works of art that refashion old objects and break down conventions. Many of his piece have power and venom and confront the Chinese government. Among these is a work shown at the Shanghai Biennial called “Fuck Off.” A favorite among art collectors who often pay sizeable sums for his works at auction, he has a highest international profile as an artist, dissident and critic of the Chinese government.

“Ai Weiwei is perhaps China’s most famous living artist and its most vociferous domestic critic, titles of a sort this committed iconoclast disdains,” Michael Wines wrote in the New York Times. — Artistically, he can do almost anything he wishes, like personally shipping16 40-foot containers, including 9,000 custom-made children’s backpacks, from Beijing for his recent exhibition in Munich.” In 2011 Ai was ranked No. 13 in Art Review magazine’s list of the 100 most powerful figures in art. [Source: Michael Wines, New York Times, November 27, 2009]

The Chinese poet Bei Ling wrote in the South China Morning, “Ai has two historic achievements: he is the most well-known and internationally influential Chinese artist and he is the most well-known protester and opposition force in mainland politics. In these dark days, he has become a mythical figure, riding forth, naked on his trusted grass mud horse...Ai's blog was visited 3.5 million times before it was closed. It was an important sign civil society was growing in the mainland. Ai kept up his dialogue with internet users on Twitter: @aiww had 70,000 followers. Ai enlightened their civil conscience and revealed to them a dark side of one-party rule. [Source: Bei Ling, South China Morning Post Magazine August 28, 2011, Translation by Jacqueline and Martin Winter ]

See Separate Articles: 20TH CENTURY CHINESE ARTISTS: QI BAISHI ZHANG, DAQIAN AND OTHERS factsanddetails.com ; MAO ERA ART factsanddetails.com ; MODERN ART IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE MODERN ARTISTS: CAI GUO-QIANG, ZENG FANZHI, WANG GUANGYI AND OTHERS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE SHOCK ART, BODY PARTS, PHOTOGRAPHERS AND VIDEO AND GRAFFITI ARTISTS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE ART MARKET: COLLECTORS, AUCTIONS, HISTORY, PROFITS AND BRIBERY factsanddetails.com ; FORGING, BREAKING AND COPYING CHINESE ART factsanddetails.com ; HIGH PRICES PAID FOR CHINESE ART factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Art Scene China Art Scene China ; Artron en.artron.net ; Saatchi Gallery saatchi-gallery.co.uk ; Graphic Arts washington.edu ; Yishu Journal yishujournal.com ; Asia Society asiasociety.org ; Art in Beijing Factory 798 in Beijing Wikipedia Wikipedia; Communist China Posters Landsberger Posters ; More Posters chinaposters.org ; More Posters still Ann Tompkins and Lincoln Cushing Collection ; Chinese Modern Artists Cai Guo Qiang.com caiguoqiang.com Guggenheim Show guggenheim.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Zhang Xiaogang Saatchi Gallery saatchi-gallery.co.uk Wikipedia article ; Wikipedia ; Various works artnet.de ; Yue Minjun Works artnet.com Book: “Ai Weiwei’s Blog: Writings, Interviews, and Digital Rants (2006-2009)”, edited and translated by Lee Ambrozy (MIT Press, 2009). Film: Alison Klayman has followed Ai Wei Wei with a camera for several years across several continents. Her inside account of Ai’s life tonight was featured on the PBS series “Frontline. The piece, “Who’s Afraid of Ai Weiwei,” is adapted from her upcoming documentary “Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry.”

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Art of Contemporary China” by Jiang Jiehong Amazon.com; The Art of Modern China by Julia F. Andrews and Kuiyi Shen Amazon.com; “A Modern History of China's Art Market” by Kejia Wu Amazon.com; “Modern Art for a Modern China” by Yiyan Wang | Amazon.com; “From Mao's Art Soldier to Xi’s Cartoonist: Political Cartoons” by Shaomin Li Amazon.com; “Chinese Propaganda Posters” by Anchee Min and Stefan R. Landsberger Amazon.com; “Cultural Revolution and Revolutionary Culture” by Alessandro Russo Amazon.com; “The Art of Resistance: Painting by Candlelight in Mao's China” by Shelley Drake Hawks Amazon.com; “Art Mao: The Big Little Red Book of Maoist Art Since 1949" by Pia Copper and Francesca Dal Lago Amazon.com; “Mao Zedong’s “Talks at the Yan’an Conference on Literature and Ar

Ai Weiwei’s Father

“Ai Weiwei’s father, Ai Qing, was both an artist and one of China’s most revered contemporary poets, who as a young man studied Baudelaire and Mayakovski in Paris. When he returned to Shanghai in 1932, the ruling Kuomintang party jailed and tortured him, calling him a leftist. It was right: in 1941, Ai Qing joined the Communist Party.”[Source: Michael Wines, New York Times, November 27, 2009]

Ai Qing was born with the name Jiang Zhenghan. After his he was jailed and tortured by the Nationalist Party (KMT) in the 1930s for his left-wing literary views, he continued to write but found so execrable the fact that he and the leader of the KMT, Chiang Kai-shek (Jiang Jieshi) had the same surname that he created in protest an alternative pronounced "Ai." Ai Qing, who was denounced during the Anti-Rightist Movement in the late 1950s. When Ai Weiwei he was two, his father was banished to the remote western region of Xinjiang. “But 17 years later, in the infancy of Mao’s new People’s Republic, Ai Qing ran afoul of the Communist Party for subtly criticizing its suppression of free speech. The party exiled him, first to Manchuria, then to remotest northwest China; Siberia, essentially. There he and his family lived in a hut dug into the ground. His job for the next 16 years was to clean out the village’s public toilets.” He was 60 years old. He had never done physical work in his life and he had to start doing it, his son said. Every night, he comes home very, very dirty. But he says, “For 60 years, I don’t know who cleans my toilets. So now I do something for them.” That’s something I learned from him. He became very powerful in terms of his thinking. He made the toilet so clean, he would see it as a work of art.”

“The family returned to Beijing in 1976, with the end of the Cultural Revolution. In 1985, the elder Ai, now rehabilitated, would receive a literary award from President François Mitterrand of France. His son, on the other hand, could hardly wait to flee China.” In the mid 2000s, Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao quoted a famous Chinese poem by Ai Qing: “If you ask me what happiness means, I tell you to ask a meadow in bloom, or a river that’s no longer frozen.”

Ai Weiwei’s Life

comforever Ai was born in Beijing in 1957. He has had a turbulent relationship with authorities in China ever since the age of 10, when his family was exiled to Xinjiang labor camp, after his father, once Mao’s favorite poet, was labeled “an enemy of the people” and banished, along with his family, to forced to do menial labor and clean latrines for his political views, first at farms in Heilongjiang Province and later in camps in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. Ai Weiwei grew up in the camps. He had to help his father clean public toilets every day for five years. He has claimed he did not brush his teeth before he turned 17. In 1978, after the Cultural Revolution, Ai enrolled in the Beijing Film Academy.

Holland Cotter wrote in the New York Times, “Ai remembers that time and its hardships. He also remembers his father’s unshattered utopian ideals. His own political coming of age coincided with the family’s return to Beijing in 1976, at a period of relative liberalism, putting him in touch with a nascent democracy movement.” [Source: Holland Cotter, New York Times, April 5, 2011]

Ai graduated from the Beijing Film Academy in 1978, but he learned and developed his artistic talents in the United States. He left for the United States in 1981 and remained there for more than a decade in the eighties and early nineties and still has an apartment here. In New York Ai became familiar with contemporary art, resulting in an expansion of his artistic activities to include sculpture and photography. Ai said, he was in the city’s art scene, not of it. He held temporary jobs and moved 10 times, throwing out his canvases each time for lack of storage room.” Cotter wrote he had no American career to speak of — New York wasn’t looking at contemporary Chinese art in the 1980s — but he circulated widely in the downtown art world and learned a lot. [Sources: Ibid, Michael Wines, New York Times, November 27, 2009]

“When his father fell ill in 1993, he agonized over returning to his homeland, which harbored such painful memories. But after 1989, and the silencing of protesters at Tiananmen Square, he had decided that the world became different. And so he returned to China in 1993, reckoning that one day he might face something like his father’s fate.” "In Beijing he helped spearhead new, radical, often conceptually based underground movements,” Cotter wrote. “And with his big-picture view of international art and his fluent English, he was a primary spokesman for new Chinese art and a link between Chinese artists and a developing audience of Western collectors, curators and critics.”

The Chinese writer Ma Jian, author of “Beijing Coma” wrote in an article published by Project Syndicate: “Ai’s Shanghai workshop used to be a salon for Chinese artists, including the film directors Chen Kaige and Jiang Wen. But Ai never allowed himself to be hired as an official regime hack. Instead, he remained an outspoken, independent man, ready to speak and take action whenever art and ideals confronted repression and cruelty.

Ai Weiwei’s Naked Photographs in New York

Bowl Pearls In 1981, he quit and flew to New York, in the United States. He enrolled in language courses in Philadelphia and California but didn't like the schools and would not graduate. Nonetheless, in 1983, Ai won a scholarship to Parsons School of Design in New York. After a year, he failed an art-history test because, it was said, he had skipped too many classes. After the school had stopped his scholarship, Ai became an illegal alien. He lived in the East Village for 10 years, along with poets and musicians, punks, Buddhists and Hindus, junkies and thieves, at the mouth of a smoking volcano, as he called it. [Source: Bei Ling, South China Morning Post Magazine August 28, 2011, Translation by Jacqueline and Martin Winter ]

The Chinese poet Bei Ling wrote in the South China Morning,” In October 1988, I arrived in New York for the first time. Poet and painter Yan Li, a member of the Beijing artist group The Stars, took me to meet Ai. He had wild hair, a Chinese army coat and was already gaining weight. Whenever he met someone new, a shy smile creased his face. He even blushed a little. Then he would say, in the most natural voice: "Let's get naked together! This is New York." To be photographed naked or half-naked is part of Ai's character, and a trait of his artistic career. He began to take nude pictures of himself and others in the mid-1980s, in his basement apartment and on the streets of New York's East Village. It was fun; it was a kind of catharsis, and developed into a deliberate show of scorn, a physical confrontation with state power.

I had just arrived and was completely dazzled by this chaotic city. Yes, I was a rebel at heart, but I wasn't ready for a nude photo. He saw that I was bewildered, smiled his mischievous smile and said again: "How about a picture? Let's take our clothes off together!" After hanging out with him on the streets for a while, I was quickly persuaded to do it. But then I sobered up, so to speak, and reneged. If I had had the misfortune of staying at his place for a few days, like many of my friends, I wouldn't have been able to escape his camera.

When Ai felt bored, he took photos of himself in the mirror. That was the beginning of his craving for "the naked". But what he really enjoyed was taking the pictures in the street, where it was forbidden. He would look around for police and if they weren't watching, he pulled down his trousers, took a shot of himself, got dressed again and disappeared. In Ai's basement I saw dozens of photos of naked artists and friends, many of them pictured with Ai. The best one was from 1986: Ai and Yan in the square in front of the World Trade Centre, on what today is known as Ground Zero. Two skinny naked young men laughing merrily into the camera.

In May 2009, Ai told mainland magazine Southern Weekend: "Yan Li wanted to take a photo of us there; that was too boring for me. I said let's get naked and then take a picture. He hesitated, but he felt that his figure was better than mine, so he did it. This was great. There we were in the sun, nobody else around. That was a time without emperors."

Ai Weiwei’s Life in New York

documenta Bei Ling wrote in the South China Morning, “Ai's apartment was also an underground shop for second-hand cameras. He always had dozens of cameras lying around, bought on the cheap from fences and thieves. He became adept at repairing them and would sell them on.” [Source: Bei Ling, South China Morning Post Magazine August 28, 2011, Translation by Jacqueline and Martin Winter ]

After the 1989 massacre in Beijing, I stayed in the US as a kind of literature refugee. I had an invitation from Brown University. I became a resident writer there, with a monthly stipend of US$1,500. I had won the lottery, so to speak, and Ai got wind of this. Whenever I was in Manhattan, he would want me to come to his famous basement. Once, as soon as I was inside, he led me to a bed covered with cameras and introduced me to all kinds of features on every one of them. He was determined to share my fortune and I was overwhelmed by his mercurial effort, so I pulled out more than US$400 for one of his cameras. As soon as Ai pocketed the money, he was so happy he took me to Chinatown for dinner. The camera didn't have extra lenses, and I never used it. It got lost somewhere in those restless years.

He was boundless and carefree. Those 10 years in New York were, in his own words, "a time when I opened my eyes in the morning and didn't know what I would do the whole day". Every day, Ai would leave his 800 sq ft basement, for which he paid US$700 rent, and climb up to the surface world, with all its serious business, to create the excitement and adventure he craved. You'd always bump into him in the early 90s, with his typical north China face and his already chubby figure wrapped in an army coat. I suspected he wore nothing under that coat. Maybe he had picked up this habit in his youth, in the Gobi Desert.

By the late 80s, Ai's rebellious character had been revealed. He was always looking for trouble. In those years, there were countless demonstrations on the streets of New York and Ai took part in every one. There were the Chinese demonstrations in 1989, but Ai also participated in demonstrations against the Gulf war (1990-1991), against police brutality and in support of homosexuals, the homeless and vagabonds.

One time he was in a demonstration that left the East Village and went into Greenwich Village, where the demonstrators were not familiar with the streets. He was cornered by the police, his camera smashed and he was thrown rather far. Ai was also threatened by police with film cameras - they came very close until the lens almost touched his face. Plain-clothes policemen would walk up to him, smiling, and give him a push, or a shove. These experiences proved valuable for him in his encounters with mainland security officials. His fearlessness in his homeland comes from his experiences in New York.

"To be threatened can get you hooked," Ai told Southern Weekend. "When state power concentrates its affections on you, you feel important." Experiences in New York — made me understand the power structure; the relationship between the government, or the people in power, and the ordinary people. It is a society that propagates freedom and democracy but, actually, power is the same wherever you go. It is completely the same."

Ai Weiwei, Allen Ginsberg, Practical Jokes and Blackjack

The Chinese poet Bei Ling wrote in the South China Morning,”At that time, Ginsberg also lived in the East Village. He always carried a little camera, which must have been expensive, but didn't look like much. He would wander around the streets and subway stops, always taking shots. I often ran into Ginsberg in the East Village, he would always keep babbling at me while he photographed everybody; he was hooked alright. Ai and Ginsberg were very close. [Source: Bei Ling, South China Morning Post Magazine August 28, 2011, Translation by Jacqueline and Martin Winter ]

Ai was also close to African-Americans and street artists. He was always up for practical jokes. The famous Chinese director Feng Xiaogang was in New York in the early 90s doing a television series called Beijingers in New York. Feng wrote about his assistant director, Ai: "He picked up two different things which had nothing to do with each other, joined them together and had them bring forth something new."

For example, he put a basketball into a bag and threw it from a tall building, just to watch people stop in their tracks and wonder what it was. Another time he bought an LP record from the Cultural Revolution: a collection of Mao Zedong's most famous essays, including, among others, the one about the old man who moved a mountain and the one on Norman Bethune, the Canadian doctor who became a hero in the mainland. They were recited by a China Central Television announcer with oratorical perfection. Ai found a record player and an amplifier, and treated the whole Village to an impromptu Maoist street oration.

Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times: “According to an article published on blackjackchamp.com, a Web site that reports on the casino industry Mr. Ai was well known among blackjack players in the United States when he lived in New York from 1981 to 1993, making frequent trips to Atlantic City. Playing blackjack was his main source of income for many years. According to blackjackchamp.com, Mr. Ai was a rated blackjack player, and so casinos gave him free suites, limos and dinners. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, April 13, 2011]

A veteran blackjack player named Vinnie told the Web site about his first meeting with Mr. Ai in Atlantic City: “I was playing and losing bad, and then this Asian guy with a beard right out of the kung fu movies, playing next to me, starts telling me when to hit, split or stay.” The Web site reported that after Ai was arrested in April 2011 some “casino insiders” were thinking of holding a series of fund-raising blackjack and poker tournaments to lobby the United States government to impose trade restrictions on China unless Mr. Ai is released.

Ai Weiwei’s Personality and Character

Bed Ai has been described as charismatic, larger-than-life, intense, gentle and affable.” “At 52, — Wines wrote. “Ai, a beefy, bearded man with an air of almost monastic composure, is an international figure in the art world, successful beyond what anyone might have predicted even a decade ago. He is a celebrated architect, a co-designer of Beijing’s landmark Bird’s Nest Olympic stadium, an installation artist and a documentary filmmaker with a 100-member staff.” [Source: Michael Wines, New York Times, November 27, 2009]

Nicholas Logsdail, director of the Lisson Gallery in London, which did an exhibition of his work, wrote in The Guardian: “I've met him on a number of occasions over the last couple of years. When we were preparing for the show, I found him to be highly practical and thoroughly professional. He is a serious man of few words but he has an ironic sense of humor. He's also a big guy, physically, with a barrel chest and a commanding presence. [Source: Nicholas Logsdail, The Guardian, May 8, 2011]

We had some very interesting conversations about the time he spent living in New York in considerable hardship. He was an exile, partly by choice, partly out of necessity because of his family's political problems in China. It was a gestation period, a time of growth. He was taking stock of the bigger world and putting his house in order, as an artist and an intellectual.”

“He may not think of himself as an intellectual, but I would certainly describe him as one. Although he can be irrational himself, he despises irrationality and tries to give a clear and logical approach to the issues that are important to him. He's committed and idealistic, and unaccepting of injustice to the point of self-denial allowing himself to get into this position is surely a form of self-denial.”

The Chinese poet Bei Ling wrote in the South China Morning,” Ai Weiwei is a big, brawny hulk of an artist who has given his weight as 280 pounds (127kg). He has a tiger's back and a bear's waist, with a bearded face that shows he's from the north. His good-natured smile hides a certain scorn. He is not loquacious but when he speaks, his words are sharp and to the point. He has a vast knowledge of political reality in the mainland. [Source: Bei Ling, South China Morning Post Magazine August 28, 2011, Translation by Jacqueline and Martin Winter ]

“When discussing Ai, you have to begin with his innate wildness... Ai doesn't like to have conversations with serious or boring people. As soon as he encounters serious talk, he becomes uncomfortable, so he has to do something absurd, any kind of practical joke, to turn a boring situation into something funny. He has always thought there are too many serious people in this world, keeping up appearances. So he has to try to make people laugh, show them the naked truth.”

Ai Weiwei Art Career

Chairs Art critic Holland Cotter wrote in the New York Times: “From a Western perspective, Mr. Ai’s career fits a familiar profile. We tend to like our contemporary Chinese artists to come across as aesthetic tradition-busters. In this regard Mr. Ai has not disappointed. In the 1990s he painted Coca-Cola logos on ancient Chinese pots and broke up classical Chinese furniture.”[Source: Holland Cotter, New York Times, April 5, 2011]

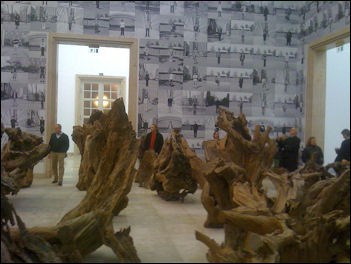

“But gradually such Duchampian moves have given way to large-scale, socially critical projects. For a conceptual piece called “Fairytale” at the 200 7Documenta in Kassel, Germany, he placed 1,001 antique Chinese chairs, available for use, throughout the exhibition. He built an outdoor structure from 1,001 doors salvaged from Ming and Qing houses that had been eliminated by rampant development in Chinese cities. Through the Internet he recruited 1,001 Chinese citizen-volunteers to come to Kassel to live for the duration of the show.”

“In short, he brought a sense of China that was at once inviting, puzzling and pathetic. The chairs were nice to sit in. It was hard to know what to make of the mini-army of temporary residents, who seemed equally uncertain of why they were there. The structure built from old doors finally just collapsed. Over all, “Fairytale” was not a winning picture of his homeland.”

“As an international celebrity he was still a feather in China’s cap at a time when the country was making an all-out effort to become a major cultural presence prior to the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics. With this in mind the Chinese government asked Mr. Ai to collaborate with the Swiss architectural firm Herzog & de Meuron on the design for the Olympic stadium, known the Bird’s Nest. He did so. The result was a triumph.”

“Through all of this, his own work, which came to include sculpture, photography, performance and architecture, fit no definable mode. It was his personal presence as impresario, entrepreneur and social commentator that gave it unity. And increasingly it was the critical commentary that stood out, became a form of performance art, carefully choreographed in all its moves. And those moves were toward ever greater risk.”

“His attacks on political authority grew sharper, more persistent, more amplified. The noble Confucian model of the morally grounded intellectual speaking truth to power in a single dramatic confrontation was called on so often as to become, seemingly by intention, an unnoble and relentless insistence. And as a result, whatever immunity from reprisal he might once have enjoyed was soon gone.”

Ai Weiwei’s Art

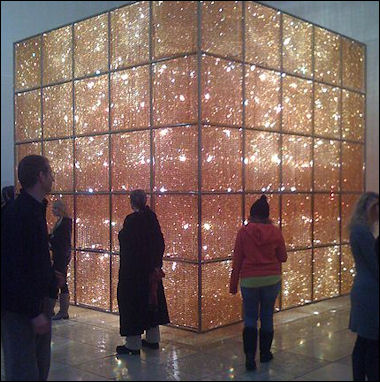

Cube Light Mr Ai is famous in artistic circles for performance pieces that explored the dizzying change of contemporary China and for irreverent, avant garde works such as a photo series that shows him giving the middle finger to landmarks such as Tiananmen Square and the Forbidden City in Beijing, the White House in Washington, and the Eiffel Tower in Paris.

Nicholas Logsdail, director of the Lisson Gallery in London, which did an exhibition of his work, wrote in The Guardian: “In my opinion, Ai Weiwei is one of the major artists of the early 21st century... He's not just the most important Chinese artist of his generation but a truly international figure... His work is a very interesting blend of traditionalism and liberalism, with a revolutionary bent. He has an outspoken nature, which is what has got him into trouble, but my reading is that his primary impulse is less to overturn society than to improve it. He is unwilling to keep quiet in the face of ignorance and prejudice and he speaks out against injustice wherever he finds it.”

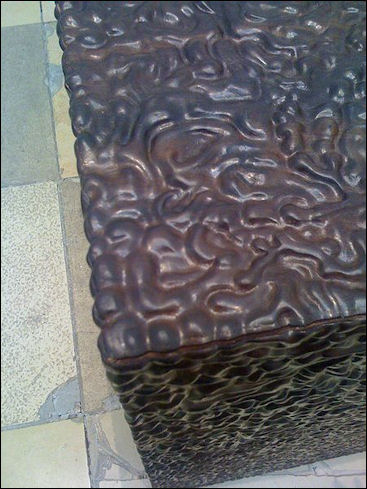

Michael Wines wrote in the New York Times, “In one of his early acclaimed works, a series of three photographs called Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, he dispassionately shatters a priceless ancient Chinese vase, striking a theme — destruction and recreation — that runs through much of his art. Other works employ Ming and Qin period urns, furniture and architecture, assembled into haunting new creations, or painted over, Warhol-style, with the Coca-Cola logo, or speared by wooden beams. [Source: Michael Wines, New York Times, November 27, 2009]

Ai served as the artistic consultant on the Beijing National Stadium for the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Ai now regrets participating in the"Bird's Nest" project. "The Beijing Olympics have oppressed the life of the general public with the latest technologies and a security apparatus of 700,000 guards. It was merely a stage for a political party [the Chinese Communist Party] to advertise its glory to the world," he said. "I became disenchanted [over the project] because I realized I was used by the government to spread their patriotic education. Since the Olympics, I haven't looked at [the stadium]," he said.

In Munich, Ai exhibited a work called So Sorry addressed to the government’s near-silence on schoolchildren who died in the Sichuan Earthquake. Describing by the New York Times as his — most arresting work of art to date — it comprises 9,000 children’s backpacks, covering one exterior wall of the Haus der Kunst museum . Against a blue background, colored bags form the Chinese characters for the message, ‘she lived happily on this earth for seven years,” a quotation from a mother of one earthquake victim.

Ai and Art with the Naked Body

The Chinese poet Bei Ling wrote in the South China Morning, “Ai is an energetic and prolific concept artist. The word "concept" includes for him his own concept of society, of the world in general. In his 10 years as an illegal alien in New York, he spent a lot of time in museums and galleries. He always walked everywhere, so he would pass 40 to 50 blocks walking to the Museum of Modern Art or the Metropolitan Museum, for example. He often talked about his enthusiasm for Andy Warhol. Ai may be one of the very few people who have thoroughly digested and understood Warhol. But he goes further than the pop-art pioneer, because he uses concepts to challenge state power. [Source: Bei Ling, South China Morning Post Magazine August 28, 2011, Translation by Jacqueline and Martin Winter ]

Ai remains preoccupied with the naked body. After he returned to the mainland, in 1993, his nude performance pieces gradually acquired levels of metaphor and satire. There is a famous photograph from Tiananmen Square, taken on June 4, 1994, the fifth anniversary of the massacre. With the skills he had learned in New York, Ai and his girlfriend, Lu Qing, were able to move through rows of police and plain-clothes detectives, to the middle of the square, opposite the portrait of Mao. Lu, who became Ai's wife, positioned herself in front of a fence, with Mao's face between her and another woman. Ai's camera captured the moment she raised her skirt and revealed her underwear, with one of her feet drawn up, as in a dancing pose. The challenge to the authorities is obvious when you see the picture but there's hardly anything illegal in it. The photo was published in underground art publications throughout the rest of the 90s.

After 2000, in the age of the digital camera, Ai became more forthright when photographing his own body. His pictures became more vulgar, flouting aesthetic standards and feelings of shame. In September 2008, he took shots of his bulging belly and posted them on his blog. These images were meant to be shocking and make the observer reflect on ugliness. The burning cigarette in his navel certainly looked vulgar enough. But there was no hidden intention to be discerned behind the vulgarity. All you can see is a shameless ageing man, who has never changed the naughty ways that have always been natural to him.

The peak of Ai's nude online presence was reached with a series of photos of himself alone or in a group, each with characteristic titles. In May 2009, Ai took five pictures. One of the pictures' titles could be translated as "the grass mud horse blocking the centre", another one as "flying high, don't forget to hide the central authority".

"Hiding" and "blocking the centre of power" are puns, because "hiding" and "blocking" sound like "party" in Chinese, and "the party centre" always means the Communist Party's Central Committee. "Flying high, don't forget the party centre" and "flying high, don't forget to hide the central authority" sound exactly the same (tengfei bu wang dang zhongyang; "flying high" is a phrase often used in state propaganda to celebrate economic or political successes). The phrase "grass mud horse" is another pun, being phonetically similar to "f*** your mother"

Ai Weiwei’s One Tiger, Eight Breasts

Dust to Dust Bei Ling wrote in the South China Morning, “On April 3, Ai was seized by security agents at Beijing airport (SEHK: 0694), as he was about to board a plane to Hong Kong. After he disappeared into incarceration, internet users, including government-paid agents (the "50-cent crew") searched frantically for nude pictures of Ai. One series of images became widely known under the online moniker "One Tiger, Eight Breasts". Many interpretations of these images have been offered. [Source: Bei Ling, South China Morning Post Magazine August 28, 2011, Translation by Jacqueline and Martin Winter ]

The classic interpretation of the group image runs like this: Ai sits in command at the centre. His manner is straightforward, but almost accidentally his hands cover the vital parts, which evokes an illusion to the Central Committee. Ai's hands rest on his left knee, indicating a resolute leftist stance.

The long-haired young woman on the left of the picture sits with her legs crossed on a backless chair. She symbolises the intellectual, since she has her own position and posture, but she has no backing and cannot be relied on. She's playing with her hair while her body is inclined towards the party centre, which means whatever intellectuals are playing at, they will always be dragged away by the government.

The woman on the right (Ye Haiyan, an activist from Wuhan, Hubei province) has a well-rounded figure and wears a jade pendant and a watch, so she's the bourgeoisie; she has a position, which can be relied on. Her hands are kept at her right side, hinting at her rightist standpoint. In the composition of the whole picture, there is an obvious distance between the party centre and the bourgeoisie. They are on polite and formal terms. The figures of the bourgeoisie and the party centre can be seen in other pictures, with different postures, meaning they have secret dealings.

The short-haired woman in the centre, sharing a seat with Ai, doesn't have her own position to sit on, so she must have been standing and smiling politely before she was pulled in and made to rest with the Central Committee. She is the media, kept in her place by the party. Finally, the girl at the back having to hide all the way behind the chairs is a migrant labourer and therefore in a classless position. It's all in the eye of the beholder, whether you see moral turpitude, a romantic situation or a tableau of political hints. This picture continues the style of Ai's other nude art projects. There is a natural and carefree attitude in the poses and expressions of the models. The pictures are not indecent - and the interpretation above does seem to be rather far-fetched, on the whole.

Who’s Afraid of Ai Weiwei Ai Weiwei’s Films

Bei Ling wrote in the South China Morning,” Who is afraid of Ai Weiwei” Ai has many names. "Wei" is a basic character, one of the 12 earthly branches used for time-keeping; commonly, "wei" means "not yet". The family name Ai is also a simple character, a name Weiwei's father, Ai Qing, chose for himself at the beginning of his artistic career. To confuse government-paid internet agents, Ai has used the Chinese characters for "ai" and "wei" in many combinations. The most common abbreviation in roman letters is aiww, as used for his Twitter account. Who is afraid of Ai Weiwei” Well, one thing is clear: Ai himself acted as if he feared nothing and no one. [Source: Bei Ling, South China Morning Post Magazine August 28, 2011, Translation by Jacqueline and Martin Winter ]

Sunflower at the Tate Ai does not just like to get naked by himself or with friends, he has also helped to lay bare "China", from the Central Committee to regional administrations. His approach is different from the serious mien of the traditional dissident intellectual. He has his own brand of indignation, mixed with an easy humour, to face the violence of state power.

Ai knew prison was waiting for him, that he could even lose his life. "Who says I am not afraid? I am very much afraid, but if I stop and do nothing, it would feel even more terrible," he told me in 2009, at the opening of an exhibition of his in Munich, Germany. Ai had a bandage on his head after having had emergency surgery as a result of a beating he'd received from police in Chengdu, Sichuan province.

Ai's 40-odd collaborators have a strong team spirit. In 2009, artist Yang Licai, who worked at Ai's studio, told Taiwan's China Times: "Ai Weiwei is not just one man on a quest. There is a band of fellow Don Quixotes riding along with him, and behind every one of them is a very dedicated crew. And behind all of them are untold and unseen masses of people. They have no other common goal than to lead a decent life."

Ai Weiwei’s film “Disturbing the Peacea” is a god example of his irreverent and aggressive filmmaking, especially when dealing with the police. The question of “respect” comes up in discussion of the film. Some audience asked whether he was disrespectful to the police and forcing the camera into people’s faces; others commented on the various ways the film camera might have intervened into the interactions captured on the screen, whether filmmaking spurred violence and confrontation at times, while repressing them at other times.

Ai Wei Wei’s Tate Gallery Instillation

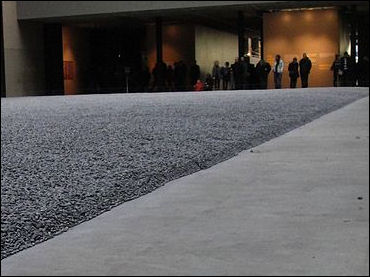

The Tate Modern gallery in London hosted Ai's huge installation "Sunflower Seeds" made up 100 million hand-crafted porcelain seeds placed on the floor in the cavernous Turbine Hall. The sunflower seeds exhibition was enthusiastically received by critics, but ran into controversy when visitors were barred from walking on them because of the ceramic dust thrown up.

On the piece,Salman Rushdie wrote in New York Times, “The great Turbine Hall at London’s Tate Modern, a former power station, is a notoriously difficult space for an artist to fill with authority. Its immensity can dwarf the imaginations of all but a select tribe of modern artists who understand the mysteries of scale. Last October the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei covered the floor with his "Sunflower Seeds": 100 million tiny porcelain objects, each handmade by a master craftsman, no two identical. The installation was a carpet of life, multitudinous, inexplicable and, in the best Surrealist sense, strange. The seeds were intended to be walked on, but further strangeness followed. It was discovered that when trampled they gave off a fine dust that could damage the lungs. These symbolic representations of life could, it appeared, be dangerous to the living. The exhibition was cordoned off and visitors had to walk carefully around the perimeter. [Source: Salman Rushdie, New York Times, April 19, 2011]

The Chinese writer Ma Jian, author of “Beijing Coma” wrote in an article published by Project Syndicate: “China's people, Ai's installation seems to imply, are like the millions of seeds spread across the Tate's gargantuan entrance hall. No one cares whether they are humiliated or crushed under foot (as the seeds were allowed to be at the exhibition's opening). Unfortunately, Ai has become one of the seeds, his freedom crushed by the heel of an inhuman state. “

Ai Wei Wei’s New York Chinese Zodiac

Sunflower at the Tate In May 2011 an outdoor sculptural piece by Ai called “Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads” was installed at the Pulitzer Fountain outside the Plaza Hotel in Manhattan. Holland Cotter wrote in the New York Times, “To most New Yorkers the dozen large cast-bronze animal heads, corresponding to the signs Chinese zodiac, will be simply winsome, or maybe a little freaky. To anyone knowing the historical reference behind these images, they’ll be explosive. [Source:Holland Cotter, New York Times, April 5, 2011]

“They are based on a set of similar sculptures that once adorned a fountain at the 18th-century imperial Summer Palace called Yuanming Yuan near Beijing. In 1860 French and British soldiers occupying China torched the palace and carried off the zodiac heads, an act which to this day evokes popular outrage in China as an example of colonialist humiliation and of everything hateful about the West.”

“Getting all the heads back — only some have been returned — has become an impassioned nationalist mission. When two were offered for sale at Christie’s in 2009 as part of the Yves Saint Laurent estate, there were protest demonstrations — almost never allowed in any other context — across China.”

Mark Singer wrote in The New Yorker: Ai’s first public art commission in New York is a reinterpretation of a seventeenth-century water clock — a dozen bronze animal heads representing figures of the Chinese zodiac, to be situated within the Pulitzer Fountain across from the Plaza Hotel. On a return visit to New York in 2008, Ai’s friend Larry Warsh arranged a meeting with Adrian Benepe, the Parks Commissioner. The particulars emerged in February, 2009, when Warsh showed up at the studio the morning that the artist’s son, Ai Lao, was born. [Source: Mark Singer, The New Yorker, April 18, 2011]

“For someone who has words for everything, he had no words,” Warsh recalled. “We went right away to the hospital, and he showed me the baby. That was very moving. I’m a big baby fan. Then we went back to the studio and started discussing public sculpture and what would make sense for New York City. An art historian was with us. An auction of the Yves Saint Laurent estate was taking place around the same time at Christie’s in Paris. The zodiac clock had been installed in the Old Summer Palace, in Beijing, which was looted by the French and British in 1860. Two of the animal heads eventually wound up with Saint Laurent. Since these had been stolen, there was a huge controversy. Anyway, as we sat in the studio, Weiwei had this “Aha!” moment. He would create full-size bronze derivations of all twelve of the animal heads.”

Ai Weiwei’s Political Activities

These days Ai is known as much for his politics as his art. He often makes statements like; “Freedom of expression is absolutely the most important thing for society. We don't have it in China. Internet and blogging were the only possibility for us to express ourselves. Now it is more restricted than ever. Michael Wines wrote in the New York Times, “Ai seems to be alternately tolerated and hectored by higher-ups. He was allowed to fly to Munich last year to stage a major exhibit that excoriated the government’s handling of children’s deaths in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. Yet months before, he was so severely beaten by police in Chengdu...that he needed cranial surgery to drain blood from his brain.”

Ai calls the government unimaginative, prevaricating, suspicious of its own people and utterly focused on self-preservation. He told the New York Times, “They don’t believe in liberty. They don’t believe in China before the Communists, he said. There is only one simple, clear task: to protect their control, to maintain their governing. Which is such a pity.” China’s nationalists often accuse him of shilling for the West. [Source: Michael Wines, New York Times, November 27, 2009]

Ai disavowed his role in designing the Bird’s Nest, saying the government had transformed the Olympics into a patriotic celebration instead of using them to create a more open society. He said the Olympics are a fake smile hiding China's deep troubles. He beat film-maker Martin Scorsese to a boycott and says he will not attend the opening ceremony. Instead, this summer Ai is heading a 100-strong team of architects building 100 eco-efficient houses in 100 days in Inner Mongolia.

Ai was said that he views his conflict with government officials over the Communist Party’s authoritarian rule as performance art. For many years many felt his politics and his in-your-face attacks of China’s leaders were suicidal and were amazed and what he seems to get away with. In 2010 he made a documentary on the story of Feng Zhengzu, the Chinese human rights activist who spent more than three months living in Narita airport, in Tokyo, after being denied re-entry to China eight times following a trip to see his sister in Japan. Ai said officials had told him the Shanghai government was "frustrated" about documentaries he had made. on sensitive incidents in the city.

Wei Wei’s blog assembled a list of the names of children that died in poorly-built schools in the Sichuan earthquake. After the quake, Ai used the Internet to assemble scores of volunteers who combed the disaster area, compiling a list of dead children, organized by age and school. All of them belonged to about 20 schools, whose buildings collapsed. Within a month after the earthquake he had gathered 5,010 names and drew enough attention to goad the government into compiling its own list and launch an investigation into shoddy school construction. Holland Cotter wrote in the New York Times, “As China’s official news channels broadcast upbeat videos of earthquake rescue operations, Mr. Ai was in Sichuan making his own films of the destruction, talking with distraught parents of dead or missing children and using his widely read daily blog to accuse the Sichuan officials of financial corruption that resulted in structurally faulty schools. His accusations of a cover-up extended to the highest levels in Beijing.

Ai Weiwei’s Pays for his Political Activities

Wei Wei’s blog with the Sichuan earthquake victim list was closed down on the anniversary of Tiananmen Square’s anniversary which he said was absurd because he was in the United States in 1989 and played no part in the Tiananmen protests. “Other blogs about issues political and otherwise have also been shut down. Someone has installed two video cameras outside his studio. The police are said to be scrutinizing his finances, an ominous development in a state where other political critics have been prosecuted for what appear to be concocted fiscal misdeeds.”

Ai’s friends and family have also been harassed and abused. On his blog he has posted details of altercations with state security officers who he said have started to follow him and intimidate those around him. Four plain-clothes officers interrogated his 76-year-old mother, he said. Another associate was woken at 4am and questioned for hours. [Source: The Guardian]

In his last newspaper interview before his arrest in April 2011 published in Munich's Süeddeutsche Zeitung, Ai Weiwei reflected on his work in the wake of the disappearance of many of his friends and acquaintances, whose "offenses" were those of questioning, speaking or writing. With friends like Tan Zuoren (who assisted him in collecting the names of the nearly 5,000 children whose deaths were allegedly caused by official corruption responsible for the collapse of schools in the 2008 earthquake) and others already apprehended or incarcerated, he worried that he might be next, saying that in a recent interrogation, police suggested that he "go abroad" to continue his career. When asked about his own well-being, he expressed concern about the latest campaign against free expression. He spoke with anguish about recurring nightmares of incarceration in which tourists blankly walked around the spectacle as though it was an exhibit. "They saw everything but didn't care — they simply acted as though this was quite normal — we live in a world of madness." [Source: Lionel M. Jensen, Asia Sentinel, History News Network, April 14, 2011]

Ai has never done anything illegal, said his lawyer and friend, Liu Xiaoyuan. But if he continues on his current path, getting involved in some very high-profile cases, I will get worried. Some government departments are already very annoyed about him. [Wines, Op. Cit]

Authorities Demolish Ai Weiwei’s Shanghai Studio

Ai has greatly angered officials in Shanghai for taking up two causes. Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times. “The first cause was that of Yang Jia, a Beijing resident who murdered six policemen in a Shanghai police station after being arrested and beaten for riding an unlicensed bicycle. Mr. Yang became a hero among many Chinese, and was later executed. The second cause was the Kafkaesque case of Feng Zhenghu, a lawyer and activist who spent more than three months in Tokyo’s Narita Airport after Shanghai officials denied him entry to the country. Mr. Ai had made a documentary about Mr. Feng’s predicament.” [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, January 12, 2011]

One Ton of Ebony Ai has juggled a prominent international art career with colorful campaigns against government censorship and political restrictions, often using the Internet. He has also demanded democracy for China, criticized government corruption for playing a role in the deaths of schoolchildren in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake and stridently supported Liu Xiaobo, a political prisoner who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize last year. Ai launched a “citizen’s” probe into a Shanghai fire that killed 58 people November 2010. According to AP, “He took to Twitter, prolifically tweeting not only his social criticism but his everyday doings, attracting more than 70,000 followers, even though Twitter is blocked by China’s internet filtering.

In January 2011, the new Shanghai studio designed by Ai Weiwei said a neighboring studio he had designed for a friend were completely razed at the order of government officials, apparently for having been erected without necessary planning permission . The studio was built in a developing art colony on the outskirts of Shanghai. It took two years to build, drawing luminaries from around the world, and one day to tear down. “Everything is gone,” Ai told the New York Times, “It’s all black now. They finished the job at 9 o’clock last night.” Ai had known about the order to destroy the studios for several months but was shocked to discover that workers had started the job so soon. The official demolition notice said Ai, who also has a studio in Beijing, where he is based, had not applied in advance for a project planning licence, but the artist says authorities told him they had arranged the necessary papers. Asked why the Shanghai authorities' stance had changed, Ai said: "We asked the same question. I can't tell. All the people we asked in government said 'You should know.' [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, January 12, 2011]

Ai Weiwei’s Detention

Ai Weiwei's commap In April 2011, Ai Weiwei was arrested by security agents at Beijing’s international airport as he was about to board a plane to Hong Kong. and was detained and held incommunicado for some time. Police searched his studio on the northern outskirts of Beijing, seizing computers, his Beijing lawyer Pu Zhiqiang said. "They had a search order, but they didn't say what crime he had been accused of," he said. An assistant at his studio, who asked not to be named, said she was one of eight people questioned by police Sunday, with the artist's wife and driver later also detained. Everyone apart from Ai was subsequently released, and his studio was open again. [Source: Reuters, April 4, 2011]

A few days later it was announced that Ai was under police investigation for suspected economic crimes. There were also allusions to him practicing bigamy and spreading pornography on the Internet. The Xinhua news agency said in a one-paragraph dispatch that police were investigating Ai — in accordance with the law.” At that point Ai’s wife, Lu Qing said that she still had no official confirmation from police about the investigation, and that she also had no news about where her husband was being detained. “I am waiting for news,” an emotional Lu said in a halting voice. “I so far have no information from the authorities about the fate of Ai Weiwei.”

Ai was taken from the airport by plainclothes officers on April 3, they covered his head with a black hood, put him in a car and drove him to a secret, secluded location, the source said, where he was held for two weeks, The 54-year-old was later moved to another location where two officers watched him round the clock, their faces often inches from his, even monitoring him as he slept and insisting he put his hands on top of the blanket. Ai was told that he was being put under "residential surveillance." He asked whether he could have access to a lawyer or whether his family knew of his whereabouts, and police officers told him that could take up to six months. Ai’s wife Lu Qing wrote: After he was taken away by public security organs, they demanded he sign a notice about “living under surveillance” before they brought him to a secret place in the outskirts of Beijing. [Source: Reuters]

During his detention, Ai was fed well and allowed long walks, the source said. When his wife saw him she said he had looked mentally conflicted and tense despite appearing to be in good physical health and receiving treatment for diabetes and high blood pressure. Reuters reported, “Ai endured intense psychological pressure during 81 days in secretive detention and still faces the threat of prison for alleged subversion, a source familiar with the events told Reuters. In the first broad account of Ai's treatment in detention since he was released in June, the source, who declined to be identified fearing retribution, said the 54-year-old artist was interrogated more than 50 times by police, while he was held in two secret locations. [Source: Reuters Life!, Sui-Lee Wee, August 10, 2011]

After 81 days in detention, Ai was released. He looked considerably thinner after getting out. Upon returning home, Ai thanked reporters for their concern and then did something almost unimaginable “he refused to say anything more. “I can’t talk about the case,” he said, speaking outside his home, his generous girth visibly diminished by the months in custody. “I can’t say anything.” He then politely asked the nearly two dozen journalists to leave him in peace.

Ai Weiwei Given a $2.4 Million Tax Bill

Rooted Upon On the day he was released, police officers told him he "could still be sentenced to 10 years," a source said, adding that Ai had to sign a contract stating that he would agree to the terms of his release before he could be released. Under the terms of his release Ai had to periodically report to police and was not allowed to travel abroad without official permission. Foreign Ministry spokesman, Hong Lei, said the conditions of his release applied only to his freedom of movement “he needs permission to leave Beijing “and any potential inference with the continuing investigation. “China is a country under the rule of law,” Mr. Hong said.

In November 2011, Ai Weiwei was told by the Chinese government he had to pay 15 million yuan ($2.4 million) for alleged tax evasion. Ai agonized over whether to pay the bill and tacitly admit guilt, or to fight the charge and possibly risk detention again. "I’m still very hesitant about it," Ai said in an interview. "Last night, I said: “Come on, I’m not going to pay anything.” Even if I got all the money and support from the public, police told me just yesterday: “Well, it’s good, you still have the intention to pay. If you pay, that means you admit the crime,”" Ai said. "It will justify the way they’ve arrested me. By myself, in my heart, I won’t pay a penny." [Source: Reuters, November 8, 2011]

In November 2011, Ai made a 970,000 ($1.3 million) payment to the bank account of the Chinese tax authorities. On why he paid Ai told Der Spiegel, “I can tell you a lot about the pressure from the tax bureau and the police department on me. They really, really wanted us to pay. They tried to push us hard. They said: Pay something, you should understand. But they did not tell me what I should understand. They said: If you don't pay, we will bring your case to the public security office, and then you will be facing criminal charges. By law you have to pay first, and then you can make an appeal. [Source: Der Spiegel Online, November 24, 2011]

Ai said authorities had not shown him evidence of the alleged tax evasion and had told the manager and accountant of Beijing Fake Cultural Development Ltd, which is the company accused of evading taxes, not to meet him. On whether he has seen any proof of his alleged tax evasion, Ai told der Spiegel,”No, and it is ridiculous. The only reason why they put me in jail is my involvement in politics, my criticism of the authorities. Later the excuse for my detention became my "tax problem."

Ai Weiwei Moves to Berlin; His Beijing Studio Demolished

Protesters and Ai look-a-like After his Shanghai studio was demolished in 2011 and his 81-day detention for alleged tax evasion, Ai had his passport confiscated for four years of de facto house arrest. In 2015, the artist moved to Berlin. On why he carried out his struggle against the Chinese Communist Party, Ai told der Spiegel, “Whenever there is injustice, there is tension. But in China it is very hard to release your anger unless you burn yourself or you jump from a bridge. In a society where there is no freedom of the press, it is difficult for victims to be noticed. [Source: Der Spiegel Online, November 24, 2011]

In 2018, Ai Weiwei’s Beijing studio was demolished by Chinese authorities without warning. The rental contract on the studio expired several months before. Naomi Rea wrote in Artnet News: “The 61-year-old artist revealed the news on Instagram, writing, “Today, they started to demolish my studio ‘zuo you’ in Beijing with no precaution.” The expansive space in the ZuoYou (Left Right) Art District, a former car part factory that the artist describes as an “East German style socialist factory building,” has served as the artist’s main studio since 2006. “Farewell,” Ai wrote on Instagram. [Source: Naomi Rea Artnet News, August 6, 2018]

The latest attack on his studio is not believed to be motivated by political retaliation, but rather a broader wave of gentrification and redevelopment. “Compared to a society which has never established trust in the social order, a trust in the rule of law, or a trust in any kind of unity in defending the rights of its people, what has been lost at my studio is insignificant, and I don’t even care,” Ai told NPR. “There are profoundly deeper and wider ruins in this deteriorating society where the human condition has never been respected.”

On his definition of art, Ai told Der Spiegel, “My definition of art has always been the same. It is about freedom of expression, a new way of communication. It is never about exhibiting in museums or about hanging it on the wall. Art should live in the heart of the people. Ordinary people should have the same ability to understand art as anybody else. I don't think art is elite or mysterious. I don't think anybody can separate art from politics. The intention to separate art from politics is itself a very political intention. I definitely know people who are shameless enough to give up basic values. I see this kind of art, and when I see it I feel ashamed. In China they treat art as some form of decoration, a self-indulgence. It is pretending to be art. It looks like art. It sells like art. But it is really a piece of shit.

Image Sources: Wiki commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021