CHINESE ART IN THE LATE 19TH AND EARLY 20TH CENTURIES

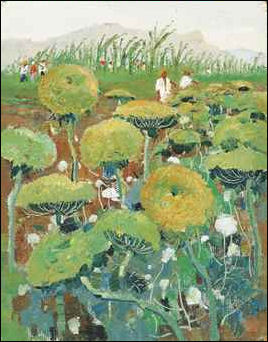

work by Wu Guanzhong

Beginning with the New Culture Movement, Chinese artists started to adopt Western techniques. It also was during this time that oil painting was introduced to China. After this, Chinese painters pursued a mix of traditional literati styles, adaptations of Western oils and other styles and systematization of folk styles. According to the Shanghai Museum:“ Since the beginning of the 20th century, Chinese painting has gradually lost the vitality. Based on traditional Chinese painting, a group of painters with revolutionary spirit absorbed skills from folk art tradition to set up a new style of painting. Others promoted Chinese painting by learning Western painting skills. They attempted to explore a new style by means of mixing Chinese and Western skills in composition, design and color. [Source: Shanghai Museum, shanghaimuseum.net]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “In the late Qing dynasty and early Republican period (late 19th to early 20th century), a surge in Western trends combined with an increase in the publication of ancient artworks were intricately related to the spirit of the times and would have a major impact on the history of Chinese painting and calligraphy both in terms of essence and expression. No longer would Chinese art follow the same patterns of development. Not only did the art of this period diverge from traditions prior to the Jiaqing and Daoguang periods (first half of the 19th century), it would emerge into an era of great revival and prosperity. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“An overview of modern Chinese painting on the mainland can generally be divided into three major systems: Northern China, Eastern China, and Southern China. Artists who took Peiping (Beijing) in the north as their home, such as Qi Huang (Baishi, 1863-1957) and P’u Ju (Hsin-yu, 1896-1963), followed more traditional paths of simplicity and elegance in their works but also formed styles of their own. Such artists as Zhao Zhiqian (1829-1884), Wu Changshi (1844-1927), and Zeng Xi (1861-1930) flourished in prosperous Shanghai, combining the lines of bronze and stone inscriptions with dense ink and colors, forming loose and rich brush manners associated with the Shanghai School. Later artists, including Xu Beihong (1895-1953) and Fu Baoshi (1904-1965), often combined elements of Chinese and Western art, creating novel approaches that innovatively knead native and foreign painting techniques together. As for Canton (Guangzhou) in the south, the seat of the Republican revolution, such Qing artists as Ju Chao (1811-1865) and his cousin formed novel methods of water and powder infusion. In the early Republican era, the artists Gao Jianfu (1879-1951), Gao Qifeng (1889-1936), and Chen Shuren (1884-1948) were three masters who had studied in Japan, developing a new aesthetic of ink and color in the Lingnan School, which has had a major influence even up to the present day. The artist Gu Gin did wonderful abstract-like geometric pieces like “A Deer Crying”.

“Calligraphy from the middle Qing onwards saw the gradual rise of the Stele School, in which adherents followed the Northern Stele School with vigorous and upright brushwork. Deng Shiru (1743-1805), Ruan Yuan (1764-1849), Bao Shichen (1775-1855), Yang Yisun (1813-1881), Zhao Zhiqian, and Weng Tonghe (1830-1904) are all examples of artists in this field. Early after the establishment of the Republic in 1911, examples of oracle bone as well as bronze and stone script emerged in increasing numbers, the influence of ancient scripts becoming further evident in the calligraphy of this period. Though it was an era of great turmoil, there were still figures with lofty ideals who took time out of their duty to country and delved into calligraphy, instilling their art with great heroic spirit. They included Yu Youren (1879-1964) and Tan Yankai (1880-1930), whose achievements far surpassed those of many of their contemporaries.

In the early years of the People's Republic, artists were encouraged to employ socialist realism. Some Soviet socialist realism was imported without modification, and painters were assigned subjects and expected to mass-produce paintings. During the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 70s, art schools were closed, and publication of art journals and major art exhibitions ceased. Nevertheless, amateur art continued to flourish throughout this period. Following the Cultural Revolution, art schools and professional organizations were reinstated. Exchanges were set up with groups of foreign artists, and Chinese artists began to experiment with new subjects and techniques.

See Separate Articles: MAO ERA ART factsanddetails.com ; MODERN ART IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE MODERN ARTISTS: CAI GUO-QIANG, ZENG FANZHI, WANG GUANGYI AND OTHERS factsanddetails.com ; AI WEI WEI: HIS LIFE, ART AND POLITICAL ACTIVITIES factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE SHOCK ART, BODY PARTS, PHOTOGRAPHERS AND VIDEO AND GRAFFITI ARTISTS factsanddetails.com ; LOOTING CHINESE ART AND ARTIFACTS AND TRYING TO GET THEM BACK factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE ART MARKET: COLLECTORS, AUCTIONS, HISTORY, PROFITS AND BRIBERY factsanddetails.com ; FORGING, BREAKING AND COPYING CHINESE ART factsanddetails.com ; HIGH PRICES PAID FOR CHINESE ART factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Art Scene China Art Scene China ; Artron en.artron.net ; Saatchi Gallery saatchi-gallery.co.uk ; Graphic Arts washington.edu ; Yishu Journal yishujournal.com ; Asia Society asiasociety.org ; Art in Beijing Factory 798 in Beijing Wikipedia Wikipedia; Communist China Posters Landsberger Posters ; More Posters chinaposters.org ; More Posters still Ann Tompkins and Lincoln Cushing Collection ; Chinese Modern Artists Cai Guo Qiang.com caiguoqiang.com Guggenheim Show guggenheim.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Zhang Xiaogang Saatchi Gallery saatchi-gallery.co.uk Wikipedia article ; Wikipedia ; Various works artnet.de ; Yue Minjun Works artnet.com Book: “A Century in Crisis: Modernity and Tradition in the Art of Twentieth-Century China”, Andrews, Julia F., and Kuiyi Shen (Guggenheim Museum, 1998)

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Chinese Painting” by James Cahill (Rizzoli 1985) Amazon.com; “Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting” by Richard M. Barnhart, et al. (Yale University Press, 1997); Amazon.com; “How to Read Chinese Paintings” by Maxwell K. Hearn (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008) Amazon.com; “Chinese Brushwork in Calligraphy and Painting: Its History, Aesthetics, and Techniques” by Kwo Da-Wei Amazon.com; Art; “The Arts of China” by Michael Sullivan and Shelagh Vainker Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery” by Patricia Bjaaland Welch Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: (World of Art) by Mary Tregear Amazon.com; “Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei” by Wen C. Fong, and James C. Y. Watt Amazon.com ; “The British Museum Book of Chinese Art” by Jessica Rawson, et al Amazon.com; “Art in China (Oxford History of Art) by Craig Clunas Amazon.com

Traditional Chinese Painting in the Twentieth Century

Nude model and students at the

Shanghai Institute in the 1920sAccording to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “ The first decades of the twentieth century marked the end of the insular, tradition-bound Qing empire (1644–1911) and the forceful entry of China into the modern age. Foreign influences, largely restricted to a handful of ports and missionary initiatives during much of the nineteenth century, now flooded into China in an irresistible tide. Indeed, the massive influx of Western ideas and products constituted the most important factor defining China's culture during the twentieth century. [Source: Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“China's defeat in the first Sino-Japanese War (1894–95) spurred a movement for reform among members of the scholarly class with the ideal of marrying "Chinese essential principles with Western practical knowledge." During its final years, the Qing dynasty did launch a number of initiatives aimed at modernization, but its efforts were too feeble and too late. Advocates for radical change, particularly the revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen (1866–1925), were able to capitalize upon growing dissatisfaction with Manchu rule to topple the Qing dynasty. The founding of the Republic of China in 1912 brought about an end to two millennia of imperial rule. During the next two decades, the young republic struggled to consolidate its power: initially by uniting central military and political leadership after the misguided attempt by Yuan Shikai (1859–1916), the first president, to establish himself as emperor; and second by bringing together China's diverse regions, after wresting control over certain areas from local warlords. In the arts, a schism developed between conservatives and innovators, between artists seeking to preserve their heritage in the face of rapid Westernization by following earlier precedents and those who advocated the reform of Chinese art through the adoption of foreign media and techniques.\^/

“As exemplified by Fu Baoshi (1904–1965) and Chang Dai-chein (1899–1983), both of whom studied in Japan and traveled abroad late in their lives, some influential artists created hybrid styles that reflected a cosmopolitan attitude toward art and a willingness to modify inherited traditions through the incorporation of foreign idioms and techniques. Zhang, who became a leading connoisseur and collector, based his diverse painting styles on the firsthand study of early masterpieces, while Fu, an academic, learned about earlier works from reproductions and copies.\^/

Zhang Daqian (Chang Dai-chein)

Zhang Daqian (Chang Dai-chein) (Zhang Daqian, Chang Dai-she, 1899-1983) is generally recognized as China's greatest 20th century painter. Born in Sichuan and regarded as a non-conformist, who worked briefly as a private calligrapher for a bandit, he mastered nearly all China styles and produced 30,000 paintings. He lived many years in South America and kept a pet gibbon. Chang was an expert forger who sold thousands of paintings attributed to classic painters.

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Chang Dai-chien (original name Yuan, sobriquet Daqian [Dai-chien] jushi), a native of Neijiang in Sichuan, was gifted in the arts of poetry and prose, painting, and calligraphy. He learned painting from his mother as a youth and also became a student of Li Ruiqing and Zeng Xi and was especially famous for his painting, in which he began by learning the tradition of copying. He went to Gansu in the 1940s and copied wall paintings at the Dunhuang grottoes. His art making rapid advances as a result. He left mainland China in 1949 and lived in such places as Argentina, Brazil and California before finally settling down at the Abode of Maya on the outskirts of Taipei in 1977.

Zhang was gifted at both the "fine line" as well as "sketching ideas" manners. He also enjoyed traveling, transforming scenery into majestic views in his paintings. He reached beyond the foundation of traditional techniques to develop a new field of splashed ink and flung colors, becoming representative of innovation in modern Chinese painting.

Among Zhang's most famous paintings are the Tang-style “Horse and Groom”, “Opera Character” (known for its expressive brush strokes), “Tibetan Women with Mastiff and Puppy “(inspired by Qin Xian), and “Clear Morning Over Lakes and Mountains” (a forgery of a 10th century painting that was sold as an original to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts).

“Copy of a Northern Wei Painting of Sumagadhi at Dunhuang Mogao Grotto 257 by “Zhang Dai-chien is an ink and colors on paper handscroll, measuring 62 x 591.7 centimeters. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “This painting, done in 1943. It is a copy from the latter half of the story of Sumagadhi on the northern wall of Mogao Cave 257. A famous painting of the Northern Wei dynasty, it depicts the lady Sumagadhi of the Sravasti kingdom burning incense to invite the Buddha to preach for a gathering of disciples. Arriving in the sky, the Buddha converted other believers through the power of the Dharma. The coloring is opulent and the rhythm undulating to make for a precise composition full of action, and some of the retouching lines are still clearly evident.

“Panoramic View of the Suao-Hualien Roadway” was done in 1965 when Zhang was 67. After Zhang Dai-chien had traveled between Suao and Hualien in Taiwan, he revisited memories of that trip to capture the misty rain-filled scenery in this painting. “Ink Lotuses” is an ink on paper framed painting, measuring 65.6 x 161.1 centimeters. Done at the age of 65 it features a bold "sketching ideas" style to render overlapping lotus blossoms and leaves. The trajectory of the brushwork is exceptionally rich with ink that flows with great moisture and harmony.

Zhang Daqian: the Great Copier

Zhang Daqian, took pleasure in fooling the experts. “Zhang Daqian felt he was an equal to the old masters,” Maxwell K. Hearn, chairman of the Asian art department at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, told the New York Times. “And so the true test was whether he could copy them.[Source: David Barboza, Graham Bowley and Amanda Cox, New York Times, October 28, 2013]

David Barboza, Graham Bowley and Amanda Cox wrote in the New York Times: “One story that illustrates Mr. Zhang’s playful approach to copying concerns his 1967 trip to review an exhibition of the works of Shitao, a 17th-century painter, at the University of Michigan Museum of Art. His tour guides were proud to show him the works of such a famous painter, who had died more than two centuries earlier. So they were surprised when Mr. Zhang began to laugh and point to various works on the wall, saying: “I did that! And that.” “That is how Zhang Daqian talked,” said Marshall Wu, a retired professor at the University of Michigan who first met Mr. Zhang in the 1960s. “You never really knew if he was serious or kidding. But he did a lot of Shitao forgeries.”

“Mr. Zhang’s work now serves as a model for a painter in Beijing, Liang Zhaojin, who studied with the master and now works in his own classical style that is based on that tradition. “I am honoring Master Zhang,” he said, “by inheriting and promoting his style.”

Zhang Daqian Tops 2011 World Art Sales, a Painting Sells for $35 Million

Zhang Daqian was the best-selling artist at auction in 2011, global market monitor Artprice told AFP, while Spanish great Pablo Picasso dropped out of the top three.Chinese artists dominate the top end of the art market. Zhang's compatriot Qi Bashi was the second top seller and six Chinese artists in all were in the top ten, while Chinese art accounts for 40 percent of sales by value. [Source: AFP, February 23, 2012]

"China, which has held the top spot in art auctions since 2010, took two of its star artists to the head of the annual table in 2011," said Thierry Ehrmann, chairman and founder of Paris-based Artprice. The third place in the Artprice table was taken by American pop art master Andy Warhol, knocking Picasso -- who died in 1973 and has been the bestseller in 13 of the past 14 years -- back into fourth place.

Zhang was not only top in sales but, according to Artprice, he had the best annual haul of any artist ever with 1,371 pieces going for a total of $554.53 million (418 million euros). Qi, who lived between 1864 and 1957, came in behind, netting art investors $510.57 million and Warhol hit $325.88 million.

In 2016, a painting by Zhang Daqian sold for nearly $35 million at an auction in Hong Kong. Farah Master and Stefanie McIntyre of Reuters wrote: “The two-meter (6.5 feet) long scroll inkbrush painting "Peach Blossom Spring" more than tripled its expected price at a spring Sotheby's sale to fetch US$34.91 million, including the buyer's premium. Kevin Ching, chief executive of Sotheby's Asia, said the 1982 work was monumental and deserved the valuation. "The colors are absolutely vibrant, and (it is) ... probably one of the two or three most important works available now in private hands," Ching told reporters. [Source: Farah Master and Stefanie McIntyre, Reuters, Apr 5, 2016]

The work is an impressionistic landscape of peach blossoms and towering turquoise mountains with a poetic inscription“Bidders battled in a packed room before the hammer came down after a tense 50 minutes, making it one of the longest auctions seen by Sotheby's in recent years. It was the most expensive Chinese painting sold at Sotheby's in Hong Kong. “The winning bid was placed by the Long Museum in Shanghai, founded by Chinese tycoon Liu Yiqian and his wife, Wang Wei, who have over the past few years bought some of the world's most expensive Chinese and Western artworks including Modigliani's 1917 "Nu couché" (Reclining Nude) for $170.4 million.

Wu Guanzhong

Wu Guanzhong (1919-2010), a master of modern Chinese painting, is regarded as one of the most important figures of 20th-century Chinese art. His landscapes, which combine Western oil painting and Chinese ink, techniques, are prized by collectors. Influenced by Post-Impressionist art, he painted a variety of subjects, including architecture, plants, animals, people and landscapes. Although many of his early works were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution he was prolific enough that many of his paintings remain. His abstract landscapes still generate a lot of attention today.

Wu Guanzhong was born in 1919 in Jiangsu Province. He studied at the École Nationale Supérieur des Beaux-arts in Paris on scholarship. While some of his contemporaries chose to stay in the West, Wu returned to China to teach at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing and other institutions. He was sent to a labor camp during the upheaval of the Cultural Revolution, and did not hold his first solo show until he was 59.[Source: Joyce Hor-Chung Lau, New York Times, June 27, 2010]

“Water Village in Jiangnan” is considered Wu Guanzhong’s masterpiece: Among his other famous works are “Ancient City of Jiaohe” and “Winter Sun”. In 2007, his “Ancient City of Jiaohe“ sold for about $5 million at the time, in Beijing. It was painted during a trip Wu took to the Xinjiang region of China. In December, his The Great Falls of Tanzania sold for around $4 million, also in Beijing. Wu died in June 2010. He was active to the end. The South China Morning Post reported that he created four last works the year he died.

Wu had an impact on the way the Western art world viewed Chinese painting. In 1992, he was the first living Chinese artist to have a solo exhibition at the British Museum in London. In 1991, France made him an officer of l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. In 2002, he was the first Chinese artist to be awarded the Médaille des Arts et Lettres by the Académie des Beaux-Arts de l’Institut de France.

Qi Baishi

Qi Baishi (1864-1957) is regarded as one of the greatest contemporary painters in China. He was influenced by Western styles but is considered by some to be the last great traditional painter of China. He painted a variety of subjects and was praised for the “freshness and spontaneity that he brought to the familiar genres of birds and flowers, insects and grasses, hermit-scholars and landscapes”. In 1953, four years before his death, Qi Baishi was elected president of the Association of Chinese Artists. In 2008 a crater on Mercury was named after him. “Eagle Standing on Pine Tree” is regarded as Qi Baishi’s masterpiece. Among his other famous paintings are “Shrimp” and “Plum Blossom.”

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Qi Baishi (original name Chunzhi, later changed to Huang) went by the style name Pingsheng and the sobriquets Baishi, Jieshanweng, and Jiping. A native of Xiangtan in Hunan who resided most of his life in Beijing, he excelled at painting landscapes, figures, and flowers-and-insects, and he was also a gifted calligrapher and seal-carver. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

David Barboza, Graham Bowley and Amanda Cox wrote in the New York Times: ““Qi Baishi was a master of the ordinary. Born in 1864 into a peasant family, herded cows and worked as a carpenter’s apprentice before taking up painting at 27. Fame came a few decades later, after he moved to Beijing and adopted a fluid, almost calligraphylike style, using an ink wash. He specialized in vivid landscapes and portraits of nature, documenting begonias, dragonflies, grasshoppers, frogs, chickens, crabs and shrimp, lots of shrimp.

“Scholars say he was prolific and estimate he produced between 10,000 and 15,000 works in his lifetime. Of those, about 3,000 are in the collections of major museums and some are assumed to have been destroyed during the Japanese invasion in the 1930s or during the Cultural Revolution, when Red Guards looted and occupied his family’s home.

In the summer of 1957, with his health deteriorating, the painter went into the studio of his traditional courtyard residence in Beijing, dabbed his brush in ink and created a portrait of a flower, a long-stemmed raspberry-and-yellow peony. Three months later, he was dead, at 93. “That was the last work he completed,” said his grandson Qi Bingyi, who keeps the painting locked in a safe at his home in Beijing. “I have it right here. Do you want to see it?” he said before unrolling the work for visitors last month.

“Squash Vines of Abundant Growth” by Qi Baishi is an ink and colors on paper hanging scroll, measuring 99 x 33.4 centimeters, at the National Palace Museum, Taipei. According to the museum: “This painting combines the methods of outlines filled with colors and "boneless" washes to depict hanging squash with long and entangled vines. The ink tones are exceptionally moist and fluid, much in a manner similar to that of gyrating "wild cursive script calligraphy. The title of the painting comes from the "Daya" section of the ancient Book of Songs. The squash, with its many seeds and vines that keep growing, has traditionally served as a blessing for many descendants and prosperity. Qi Baishi in his signature dated the work to the "yiwei" year (1945) and, according to his inscription, did in fact paint it to congratulate a friend on the birth of a son.

“Lychees” is another Qi Baishi painting at the National Palace Museum, Taipei. “This work, donated by Mr. Lin Tsung-i to the National Palace Museum, shows a rattan basket filled with luscious and colorful lychee fruit, which has attracted a rat to come and steal one. The bright red color of the lychees contrasts with the jet-black fur of the rat, creating for an appealing arrangement. The simple and bold manner of "sketching ideas" shown here was popular in Chinese painting during the first half of the twentieth century.

Two Qi Baishi Works Sell for Over US$215 Million

Qi Baishi, “Twelve Landscape Screens” (1925) is the most expensive Chinese painting ever sold at auction as of 2020. It was was sold for US$140.8 million at Poly Auction, Beijing in December 2017. Mia Forbes wrote in thecollector.com: The work is a series of ink landscapes Mia Forbes wrote in thecollector.com: “The twelve screens, which show distinct yet cohesive landscapes, uniform in size and style but different in precise subject matter, epitomize the Chinese interpretation of beauty. Accompanied by intricate calligraphy, Wu’s paintings embody the power of nature while conjuring a feeling of tranquility. He produced only one other work of this sort, another set of twelve landscape screens made for a Sichuan military commander seven years later, making this version even more valuable. [Source: Mia Forbes thecollector.com, January 2, 2021]

In May 2011, Qi Baishi’s painting “Eagle Standing on Pine Tree”sold for $65.5 million..T he Global Times reported: “An ink-wash painting by Chinese painting master Qi Baishi was sold for 425.5 million yuan ($65.5 million) during the Guardian Spring Auction at the Beijing International Hotel Convention Center. The auction started with a price of 88 million yuan ($13.5 million) and was sealed with the record price for modern and contemporary Chinese art work after more than 30 minutes of bidding. As one of the largest paintings in Qi's oeuvre, it measures 100 centimeters by 266 centimeters, with the calligraphy couplet engraved within measuring 65.8 centimeters by 264.5 centimeters. The couplet reads "A Long Life, A Peaceful World." Another piece of Qi's work was also sold for 80 million yuan ($12.3 million) at the auction. [Source: Global Times, May 23, 2011]

Qi Baishi’s “Eagle Standing On Pine Tree” (1946) was 6th most expensive work of Chinese art ever purchased as of 2020. It was bought by Hunan TV & Broadcast Intermediary Co and sold by Chinese billionaire investor and art collector, Liu Yiqian. The purchase set off a controversy. After the gavel came down the top bidder refused to pay on the grounds that the painting was a fake. Mia Forbes wrote in thecollector.com: “As well as causing chaos for China Guardian, on whose website no trace of the painting can now be found, the controversy highlighted the ongoing problem with forgery in the emergent Chinese market.The issue is exacerbated in the case of Qi Baishi by the fact that he is thought to have produced between 8,000 and 15,000 individual works during his busy career. [Source:Mia Forbes thecollector.com, January 2, 2021]

Qi Baishi: Primary Target of Chinese Forgers

David Barboza, Graham Bowley and Amanda Cox wrote in the New York Times: “When the hammer came down at an evening auction during China Guardian’s spring sale in May 2011, “Eagle Standing on a Pine Tree,” a 1946 ink painting by Qi Baishi, one of China’s 20th-century masters, had drawn a startling price: $65.4 million. No Chinese painting had ever fetched so much at auction, and, by the end of the year, the sale appeared to have global implications, helping China surpass the United States as the world’s biggest art and auction market. “But two years after the auction, Qi Baishi’s masterpiece is still languishing in a warehouse in Beijing. The winning bidder has refused to pay for the piece since doubts were raised about its authenticity. [Source: David Barboza, Graham Bowley and Amanda Cox, New York Times, October 28, 2013]

“Death, however, seems to have done little to curb Qi Baishi’s productivity, according to auction records and interviews with experts and his family. They indicate that rising values and his popularity as one of China’s greatest modern painters have led to a flood of fake Qi Baishis on the market. Liu Xilin, editor of “The Complete Works of Qi Baishi at the Beijing Fine Arts Academy,” said about half the Qi Baishi works that come up for auction in China are fake. “I can see that by just looking at their catalogs.”

“In the past 20 years, works attributed to Qi Baishi have been put up for auction more than 27,000 times in China. In one sign of the mania, 5,600 works attributed to Qi Baishi came on the market in 2011, up from 381 works in 2000. Auction records, though, show that more than 18,000 distinctive works by Qi Baishi have been offered for sale since 1993, an impossible number, if the expert estimates are right.

“In a study this year, Artron said many of China’s leading modern artists are being counterfeited, but none more so than Qi Baishi. Arnold Chang, who ran Sotheby’s Chinese painting division in the 1980s, is equally emphatic. “There is no doubt,” he said, “that there are far more works ascribed to Qi Baishi in the market than he could have possibly painted, even with an assembly line of assistants — which he supposedly had.”

“Just about every major city in China has an art dealer who claims access to high-quality Qi Baishi fakes. They are often sold as reproductions, as are many of the elaborate counterfeits created here, but experts say many of them invariably end up at auction, rebranded as the real thing. Qi Baishi’s own family, some of them painters, aggressively promote themselves as descendants of the famous artist in order to sell their works, done in his style. “Some distant relatives can’t even draw very well, and they go out and claim they are Qi Baishi’s family,” said Qi Binghui, a granddaughter of the artist, who is based in Beijing. “If you’re going to do something in your grandfather’s name, at least live up to his standard.”

“Family members say they have been pressed to authenticate fakes, to pose for photos with pieces that might go to auction and even to mass-produce famous works by Qi Baishi. “I can tell you I was once asked to go to Thailand to justify a batch of 20 fake paintings claimed to be my grandfather’s,” Qi Binghui said. “That person was trying to sell those fake paintings in Thailand, and he wanted me to assure the buyers that they were real.”

“Concern over fake Qi Baishis is now a challenge for auction houses. China Guardian, the big auction house, says it has an enviable record of spotting fakes, and most experts agree that its reputation stands above all others. But in the spring of 2011, China Guardian marketed “Eagle Standing on a Pine Tree” as the classic masterpiece the painter had created decades earlier to honor the birthday of Chiang Kai-shek, then president.

“The work was put up for sale by Liu Yiqian, a former taxi driver turned wealthy financier, who has become one of China’s largest art collectors. He sold it as a set with a calligraphic couplet Qi Baishi wrote to accompany the painting, and the auction house estimated it could bring in as much as $20 million. On a cool evening in May, bidding on the work went back and forth for more than 30 minutes as a collector in the room jousted with someone calling in bids by telephone. When the hammer fell at a record $65.4 million, the room burst into applause. The euphoria did not last long, though. An art critic, Mou Jianping, soon suggested that the work might be fake, and the bidder decided not to pay. Two years later, the buyer has effectively defaulted on the item. Mr. Liu declined to comment on the failed sale.

Pan Tianshou

Pan Tianshou (1897–1971) was a master Chinese painter and an influential educator. His “View From The Peak” (1963) was sold for US$41 million at the at China Guardian 2018 Autumn Auctions. The work displays the painter’s skill with brush and ink. According to the China Daily: After the Song Dynasty (960-1279), traditional Chinese painting gradually lost its robust and fresh features. Pan’s strokes however, absorbed the vigor of the ink painting of the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279) and the robustness of the Zhe School of that time while discarding their bluntness, thinness and rigidity. Pan developed a unique style that aimed at vigor and robustness. No theorist or painter has ever come up with such artistic ideas, and therefore Pan is distinct from not only ancient, but also modern artists. [Source: China Daily, December 5, 2017]

Pan was born in Zhejiang province, and later took up positions as president of the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts (now the China Academy of Art), vice-president of the China Artists Association and vice-president of the Xiling Seal Engravers Society. Pan believed that "those Chinese painters, who simply imitate works of ancient people those in the past without the slightest hint of innovation to bring glory on their ancestors, are purely silly descendants." All great accomplished painters in history broke through the set patterns of their predecessors and made innovations their responsibility. “Pan absorbed the strengths of other Chinese painters. He harnessed the essence of all these masters and established a style of his own, surpassing his predecessors.

Pan's style is robust, majestic, extraordinary and peculiar, with a magnificent and beautiful inner strength that triggers soul-stirring results. He said, “Each painter has a different style and it is the difference that makes art." The formation of a unique style, "first requires a national style, which differs from that of Western paintings; secondly, it needs new creation and a difference from predecessors; and thirdly, it should stand the judgment of the society and the test of history."

Pan visited Yandang Mountain several times between 1955 and 1963. Its deep ravines and beetling cliffs and wild flowers offered him "supreme rough sketches" and Pan composed some of his pinnacle works based on the landscape of Yandang Mountain. “Pan once said, "Wild flowers, masses of weeds and clustered bamboos in the ravines of remote mountains, tall or short, intertwined or disappeared, have a natural and wild quality, a fresh and elegant aesthetic conception, a gorgeous and non-secular character, which are all beyond imagination when compared to flowers in greenhouses."

For Pan, Yandang Mountain was not only a painting subject, but also a place of spiritual significance. From the ravines enveloping each other on Yandang Mountain, he learned the beauty of arranging mountains, waters and flowers in an irregular way; from bluffs and cool waterfalls, as well as strange rocks and trees, he absorbed the solidity and firmness in brushwork and modeling.

Pan was a firm carrier of cultural heritage was also a great innovator. He incorporated landscape techniques into the panoramic view of birds-and-flowers, and vibrant mountain flowers into the near landscape, for the creation of the momentous and magnificent format. "For all my life I have been a teacher, and painting is just an avocation," Pan said. In 1928, he was appointed professor of traditional Chinese painting at the National Academy of Art (today the China Academy of Art), and he stayed with this institution for the rest of his life.

Late 19th and Early 20th Century Artists in Northern China

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: ““The development of art in Northern China radiated from its center at Beijing. As the capital of the country in the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties for more than 600 years, Beijing had long served as a magnet for painters and calligraphers. With their pronounced quintessential shades of wealth and power, they gradually became known as the "Capital School." Art circles in Beijing mainly emphasized drawing sustenance from the long and rich history of tradition while also seeking a deeper sense of personal artistic language and quality. As a result, works by painters of the Capital School almost always preserve the essential spirit of traditional painting. Artists who belonged to this group included Qi Baishi (Huang, 1863-1957), Chen Shizeng (1876-1923), Jin Cheng (1878-1926), Yu Fei’an (1888-1959), P’u Hsin-yu (Ju, 1896-1963), and Wang Xuetao (1903-1982). [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Yu Fei'an (also known as Yu Zhao) was a Manchu who hailed from Penglai in Shandong but lived for some time in Beiping (Beijing). He once served as an instructor at the Chinese painting research institute attached to the Exhibition Office of Ancient Artifacts. In calligraphy, he excelled at "slender gold" script and did paintings of bird-and-flower as well as animal subjects in fine lines deriving from the manner of Song dynasty artists to create a pure and untrammeled style. “Landscape” is an ink and light colors on paper hanging scroll, measuring 70 x 44 centimeters. “Yu's inscription on this painting, done in 1948, indicates that he had recently imitated a handscroll entitled "Boat Returning on a Snowy River" by Emperor Huizong of the Song dynasty. Consequently, the mountain forms and arrangement seen here derive from the middle of that handscroll but with some adaptations to suit the hanging scroll composition. The brushwork is sharp and beautiful, the hues pure and cool, making the viewer feel the penetrating cold of the scenery.

Jin Cheng (1877-1926, style name Gongbei, sobriquet Beilou), a native of Wuxing in Zhejiang, studied law in England and also conducted a survey of Western art. In the early Republican era he served as Secretariat at the State Council and was responsible for the preparatory council for the display of artifacts from the imperial collection. He also established the Chinese Painting Research Association. Good at painting landscape and flower subjects, he likewise excelled at imitating the ancients. His work “Birds and Flowers” depicts the luxuriant shade of paulownia trees, their cones similar to small bells drooping downwards. Below the trees are Chinese rose in full bloom. A pair of mynah birds is bringing food to feed their young as they shuttle back and forth. The entire work is done in bright yet warm colors neatly arranged with light shining amongst them.

Ch'i Pai-shih (1863-1957, original name Huang, style name P'ing-sheng, and sobriquet Pai-shih) was a native of Hsiang-t'an in Hunan province. He excelled at painting landscapes, figures, and flowers-and-insects, and he was also a gifted calligrapher and seal-carver. His work “Crabs” is an ink on paper hanging scroll, measuring 102.2 x 34.1 centimeters. “Using simple brushwork in this painting, Ch'i Pai-shih was able to accurately grasp the spirit and movement of crabs. Their shells were generalized into three lines without subtracting from the appearance, the subjects in Ch'i's painting far exceeding what can be defined with a fine brush. Ch'i Pai-shih had no equal either then or before when it came to painting crabs. In addition to his personal innovation, he was able to observe and sketch them faithfully so that he could capture their every movement and appearance on paper.

Late 19th and Early 20th Century Artists in Eastern China

The east coast area of China includes Shanghai, and culturally-rick Suzhou city and Jiangsu and Zhejiang Provincees. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Art circles in Shanghai reflected a mix of Chinese and foreign cultural elements, creating extremely lively and pluralistic directions. Such famed artists as Pu Hua (1830-1911), Ren Yi (Bonian, 1840-1896), Wu Changshi (1844-1927), Huang Binhong (1865-1955), Lu Fengzi (1886-1959), Xu Beihong (1895-1953), Chang Dai-chien (1899-1983), and Fu Baoshi (1904-1965) each followed different paths of "deriving from antiquity and creating innovation" or "drawing from the West to embellish native [styles]" as they forged new and unprecedented styles for the times. In terms of calligraphy, the revered Stele School was the orthodox manner, in which artists grasped the brush to make bold and powerful strokes while combining elements of bronze and stone scripts as well as seal carving. Representative artists in this respect included Wu Xizai (1799-1870), Zhao Zhiqian (1829-1884), and Wu Changshi. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Wu Changshi (1844-1927), original name Jun; style names Changshi and Cangshi; sobriquets Foulu and Kutie; also known as Pohe, Laofou, and Dalong), a native of Anji in Zhejiang, was more commonly known by his style name after the age of seventy. At 29, Wu learned poetry and prose, calligraphy, and seal carving from Yang Xian and later became a leader figure in the Shanghai School.. When he was fifty, he began tracing back to the painting styles of Zhao Zhiqian, the Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou, Shitao, Bada shanren, Chen Chun, and Xu Wei, also using the lines from Bronze and Stele calligraphy in painting. “Red and White Chrysanthemums” by Wu is an ink and colors on paper hanging scroll, measuring 134 x 41 centimeters. “In this work, his use of brush and ink is strong and upright, possessing a heavy and dignified manner. The colors are strong as well, being filled with spirit. The white chrysanthemums were done in outlines, the red ones rendered in the "boneless" method of washes. The leaf veins resemble the careful strokes of ancient seal script, each one done with a centered brush that fuses calligraphy and painting into a natural combination.

Fu Pao-shih (1904-1965), a native of Hsin-yu in Jiangxi province, originally went by the names Chang-sheng and Jui-lin and had the sobriquet Po-shih-chai chu-jen. As a youth he studied in Japan and graduated from the Tokyo Imperial Fine Arts School. Specializing in landscape and figure painting, he synthesized Chinese and Western techniques while also studying from nature. Advocating innovation, he became one of the masters of modern Chinese painting. “A Sense of Snow “ by Fu is an Ink and light colors on paper hanging scroll, measuring 89.7 x 57.2 centimeters. “This work depicts three figures walking through mountain scenery in the snow. The painting is done in spirited brushwork, both moist and dry. The moist ink of the foreground trees and rocks creates a dramatic contrast against the blank areas of the peaks representing snow, heightening the sense of cold. The casual yet mature brushwork is also abbreviated and remote.

Ren Yi (1840-1895, style name Xiaolou and later changed to Bonian), a native of Shanyin in Zhejiang, did figure and bird-and-flower paintings in imitation of the Song dynasty double-outline technique, to which he added bright and beautiful colors. He began learning to paint from his father, Ren Hesheng, and later received instruction from Ren Xiong and Ren Xun, and excelled at painting figural and bird-and-flower subjects with lush colors and lively forms. He resided for a long time in Shanghai selling paintings and became praised by contemporaries as leader of the Shanghai School. “Flowers” by Ren is a framed ink and colors on silk leaf, measuring 26 x 26 centimeters. It “depicts the poise of plantain lily using the double-outline method. The green stalks are rendered with round and forceful brushwork, while the garden rock features sharp "nail-head" strokes. The petals are lightly washed with white, and golden outlines faintly visible express a sense of exceptional refinement. Despite the small size of this work, it conveys quite well the rich arrangement and layering of blossoms, rocks, and grasses in this garden setting. The plantain lily is known in Chinese as the "jade hairpin flower," in reference to the jade hairpins worn by ladies in ancient times and serving as a metaphor for noble virtue.

Late 19th and Early 20th Century Artists in Southern China

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The most revolutionary advances in the artistic developments of Southern China during modern times took place with the "Three Masters of Lingnan" — Gao Jianfu (1879-1951), Gao Qifeng (1889-1933), and Chen Shuren (1884-1948). These three masters initially inherited the styles of the famous masters Ju Chao (1811-1865) and Ju Lian (1828-1904) of the "Geshan School" in Guangzhou. Later traveling to Japan, they not only learned from nature in terms of technique but also paid special attention to the formation of washes and atmosphere to create a new visual aesthetic full of romanticism and lyricism. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Lin Feng-mien (1900-1991, originally named Feng-ming) was a native of Mei-hsien, Guangdong province. In 1920, he went to France to study painting and later promoted the fusion of Chinese and Western art, becoming one of the leading masters in modern Chinese art. “Lady and Lotus Blossoms” is a framed ink and colors on paper, measuring 66.4 x 66.7 centimeters. It depicts a lady in ancient dress. The artist first used brushstrokes to outline the forms and then a collage method of washes for the figure's flesh. The robes and background were both done with large patches of color washes, much like watercolor painting. The background is particularly decorative, clearly influenced by the style of Henri Matisse but still retaining a strong overall effect of traditional Chinese aesthetics.

Lin Fengmian (1900-1991, original name Lin Fengming), a native of Meixian in Guangdong, once studied in France. After returning to China, he first taught at the Beijing National Academy of the Arts and then the Hangzhou National Art College. Lin advocated reform in Chinese painting by fusing Chinese and Western methods, borrowing from the styles of Impressionism and Fauvism as well as formal elements from traditional Chinese painting and folk art, including relief brick sculptures and painted porcelains. He eventually refined them to create an extremely rich and personal artistic language. “Nude Woman” is a square painting by Lin that depicts a kneeling nude model. The lines are simple and fluent, with the background curtain rendered in large swaths formed by an ink-laden brush. In the boldness is a sense of elegant beauty that gives the subject a sense of freshness and appeal.

Late 19th and Early 20th Century Artists Who Moved to Taiwan

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “After 1949, following the retreat of the Nationalist government to Taiwan, a number of major painters and calligraphers from the mainland made their way to the island. Bringing with them styles and techniques from China, they without a doubt injected new substance to the development of the arts in Taiwan. Furthermore, Taiwan's unique geography and climate also gave new inspiration for change in the art of this generation of painters and calligraphers. Among the most famous of these are the "Three Masters from Across the Strait" — P’u Hsin-yu (Ju, 1896-1963), Huang Chun-pi (1898-1991), and Chang Dai-chien (1899-1983). Close examination of the differences between their early and later styles clearly reveals the close relationship between art and their time and place of activity. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Fu Chuan-fu (1910-2007, original name Baoqing, style name Jueweng, sobriquet Xinxiang shizhu), a native of Hangzhou in Zhejiang, came to Taiwan in 1949. Sketching the scenery of Taiwan from life, he developed the method of "fissure texturing" for painting rocks, "dot staining" for waves, and "wash staining" for seas of clouds. He actively employed traditional methods of brush and ink to pioneer a modern style of his own. “Tracing the Source of Niagara Falls” is a framed ink and colors on paper painting, measuring 44 x 88 centimeters. “Fu was famous for his "Two Perfections of Clouds and Waters." This work, donated to the National Palace Museum by the brothers Fu Li-sheng and Fu Tung-sheng, was done in 1980 based on a sketch that he had previously made on a trip to Niagara Falls, which straddles the United States and Canada. The composition here depicts a foreground cliff with rapids extending into the middleground to create an effect of half solid and half void. The brushwork is likewise succinct yet quite bold.

P'u Ju (1896-1963, style name Xinyu [Hsin-yu], self-styled "Recluse of West Mountain") was a native of Wanping in Hebei (modern Beijing). A descendant from the Qing imperial family, he was the grandson of Yixin, Prince Gong. P'u Ju moved to Taiwan in 1949 and taught at the fine arts department in National Taiwan Normal University. He excelled at the "Three Perfections" of poetry, calligraphy, and painting. “Fish, Shrimp, and Other Aquatic Creatures” is an ink and colors on paper album leaf, measuring 28 x 38 centimeters. It was done in 1962 at the age of 67 by traditional count. Composed of twelve leaves, the creatures in this album, including fish, shrimp, crabs, and shellfish, are all done in fine brushwork, the forms realistic and spirited with light and elegant colors. Each leaf also has an inscription, an ode to lodging the artist's ideas, or a record of the creature depicted, allowing the viewer to realize P'u Ju's depth of learning in addition to appreciating these works of art.

Jin Cheng (1878-1926, style name Gongbei; sobriquets Beilou and Ouhu) was born into a well-to-do family in Wuxing, exhibiting a keen interest in art since childhood. He later went to England and studied law, returning to China and serving as a legislator as he settled down in Beijing. In 1920, with Chen Hengke and others, he co-founded the Chinese Painting Research Institute to promote traditional painting. He excelled at painting landscapes and flowers, being especially gifted at copying artworks. His landscape painting first followed the styles of such painting schools in the capital associated with the Qing dynasty artists Wang Yuanqi and Wang Hui, later turning to styles of the Song and Yuan dynasties. “Landscape” is an ink on paper horizontal scroll, measuring 46.2 x 94.2 centimeters. “According to the poem inscribed on this painting, its style derives from that of Li Cheng (919-967). The work depicts layers of mountains with peaks and ridges undulating through the scenery. The brushwork is fine and the atmosphere solemn, the use of brush and ink expressing the desolate scenery of an autumn day. The painting was done in 1924.

Xiao Xun (1883?-1944, style name Qianzhong, sobriquet Dalong shanqiao), a native of Huaining in Anhui, co-founded in Bejing with Jin Cheng and others the Chinese Painting Research Institute in 1920 and also taught at the Beiping Art School. In early years he learned painting from Jiang Yun and also studied by copying the works of the Four Wangs of the Early Qing, especially those of Wang Hui. Later Xiao turned to study the style of another Qing artist, Gong Xian, creating a unique style with great variety to his brush methods. He achieved renown in Beijing painting circles for his landscape painting, becoming known with Xiao Junxian and Hu Peiheng as the "Two Xiaos and One Hu." “Joyous Record at Mt. Song” is an ink and colors on paper hanging scroll, measuring 129.7 x 63.7 centimeters. “This hanging scroll, done in 1926, depicts a lofty scholar leisurely studying in a small hut by a mountain stream. Next to the building stand hoary pines surrounded by trees and rocks. In the distance are lofty mountains enveloped in clouds and mists, where a waterfall emerges from the heights. The mountainous force appears in layers, and the composition is rich and dynamic, the coloring strong and hoary in layers clearly defined.

Pu Ru (1896-1963, also known by his style name Xinyu; sobriquet Xishan yishi) was the grandson of Yixin, Prince Gong, of the former Qing dynasty. He delved into poetry, history, painting and calligraphy since childhood. When in Beijing, he devoted himself to the study of painting, beginning with copying ancient artworks. He achieved outstanding results to create a manner of his own, being praised as the "head of the orthodox school in the blue-and-green Northern School landscape tradition in Chinese painting" and renowned along with Chang Dai-chien as "Chang of the South and Pu of the North." He later moved to Taiwan and became one of the most important masters of its Chinese painting in modern times. “Prolonged Years” is an ink and colors on paper hanging scroll, measuring 99.2 x 32.1 centimeters. “The composition of this painting is layered and complex with a mountain stream coursing through lofty and undulating peaks. The trees are lush with a winding path leading to seclusion. The coloring is warm and elegant, the brush manner beautiful and tactful, exhibiting a grand and imposing manner. With the inscription mentioning the southern mountains of immortality and the verdant age of pines, this work was done as a birthday blessing for General Ho Ying-chin (1890-1987) on his sixtieth birthday.

Ma Jin (1900-1970, style name Boyi; sobriquets Zhanru and Yunhu), a native of Beijing, joined the Chinese Painting Research Institute in 1920 and studied under Jin Cheng, copying from a wide range of ancient paintings. Fusing "fine-line" and "sketching-ideas" manners, he especially excelled at painting horses, following the style of Lang Shining (Giuseppe Castiglione; 1688-1766). He also was gifted at bird-and-flower painting, being likewise good at calligraphy and seal carving. He was active in Beijing painting circles. “Antelope Standing under Shady Pines” is an ink and colors on paper hanging scroll, measuring 151.2 x 81.1 centimeters. It “depicts an antelope standing beneath two lofty pines, the compositional arrangement and coloring completely following Giuseppe Castiglione's "Antelope with Pines and Rock" in the collection of the Beijing Palace Museum. The fine and realistic painting style accord with the original in every detail, so much that they are nearly indistinguishable and thus making this a great testimony to Ma Jin’s superlative effort at studying the painting style of Castiglione. It is also an early work by Ma, being done in 1923.

Chen Nian (1876-1970, style name Banding, which he went by; also style named Jingshan), a native of Shaoxing in Zhejiang, lived in his early years in Shanghai and was highly regarded by Wu Changshi, who personally instructed him in the "six methods" of Chinese painting and the essentials of seal carving. In middle years, Chen went to Beijing and taught at the Beiping Art School. He was good at landscape and figure painting, being also gifted at "sketching-ideas" flowers. At first he studied the styles of Ren Bonian and Wu Changshi, later turning to Ming and Qing dynasty painters, such as Xu Wei and Chen Chun. Chen Nian's brushwork is mellow and his coloring archaic yet elegant. He also enjoyed seal carving, following the master Wu Changshi and being able to achieve much of his spirit. “Narcissi, Plum Blossoms, and Rocks” is an ink and colors on paper hanging scroll, measuring 137.8 x 69.2 centimeters. This painting, done in 1961, is a rendering in "sketching ideas" that depicts a combination of plum blossoms, lake rocks, and narcissi, having much of the pure charm, serene elegance, and lofty fragrance associated with scenery of the Chinese New Year and late winter. It is also a harmonious combination of the beauty of poetry, calligraphy, painting, and seal carving.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021