MAO-ERA ART

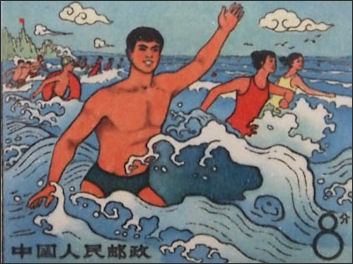

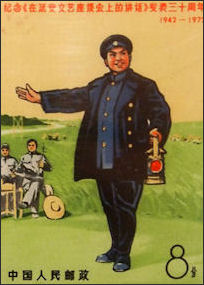

Swimming stamp (1976), Swimming was Mao's favorite sportIn the early years of the People's Republic, artists were encouraged to employ socialist realism (See Below) . Some Soviet socialist realism was imported without modification, and painters were assigned subjects and expected to mass-produce paintings. This regimen was considerably relaxed in 1953, and after the Hundred Flowers Campaign of 1956-57, traditional Chinese painting experienced a significant revival. Along with these developments in professional art circles, there was a proliferation of peasant art depicting everyday life in the rural areas on wall murals and in open-air painting exhibitions.

Communists art was supposed to represent and express the goals and needs of “The People” but mainly it to represented and expressed the goals and needs of the Chinese Communist Party. Some Chinese artists, especially those who complied with waht was expected of them, received money and support from the government. Communist attempts to institute Stalinist-style Socialist Realism in arts and literature have been largely abandoned by serious artists since the end of the Mao period in the 1970s. Classic paintings often have seals and writing on them, sometimes by the artist and sometimes by a scholar-official from a later era. Communist politicians continued this practice. Many paintings contain the writing of Chairman Mao. [Source: Eleanor Stanford, “Countries and Their Cultures”, Gale Group Inc., 2001; Stevan Harrell, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia - Eurasia / China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “With the founding of the People’s Republic of China on October 1, 1949, cultural activities came under the control of the state. Seeking to reform traditional painting to make it "serve the people," the Communist government mandated that artists pursue a "revolutionary realism" that would celebrate the heroism of the common people or convey the majesty of the motherland. Taking the Socialist Realism of the Soviet Union as orthodoxy, Chinese painters found a model among their own countrymen—emulating the Western-derived academic realism of Xu Beihong (1895–1953). Painting from life rather than copying ancient masterpieces became the principal source of inspiration for most artists. But excessive bureaucratic oversight and the shifting demands of politics often had a detrimental effect. The Communist party's effort to encourage plurality and free expression under the Hundred Flowers Movement of 1956–57, for example, was soon cut short by the antirightist purge of 1957; while the Great Leap Forward, of 1958–62, and the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution of 1966–76, although intended to bring society into conformance with the party's progressive ideals, actually led to the persecution of many well-known artists and had a stultifying impact on creativity.\^/ [Source: Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

During the Cultural Revolution, art schools were closed, and publication of art journals and major art exhibitions ceased. Nevertheless, amateur art continued to flourish throughout this period. Following the Cultural Revolution, art schools and professional organizations were reinstated. Exchanges were set up with groups of foreign artists, and Chinese artists began to experiment with new subjects and techniques.

A woman named Men Sonfzhen made a career of airbrushing out comrades who fell out of favor from Communist party photographs and taking grainy black and white photographs of Communist leaders such as Mao Zedong and retouching and painting them into heroic color portraits. "We never asked question," she told Newsweek. "We just did what we were ordered to do...We were under lots of pressure."

In 2016, a “Red Classic” ink-and-color landscape by Li Keran (1907-89) was sold for $13 million at a Beijing auction. Lin Qi wrote in in the China Daily: The painting, titled Shaoshan Mountain, the Sacred Land of Revolution, topped a sale of modern Chinese ink and water paintings staged by the Beijing Council International Auction. The 1-meter-long painting was created in 1971 and portrays a scene from the mountainous Shaoshan, in Hunan province, where the late Chairman Mao Zedong was born and spent his childhood. At the center of the painting, Li drew Mao's former residence, which attracts groups of visitors who raise red flags high into the sky. [Source: China Daily, June 8, 2016]

See Separate Articles: CULTURE UNDER THE COMMUNISTS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; 20TH CENTURY CHINESE ARTISTS: QI BAISHI ZHANG, DAQIAN AND OTHERS factsanddetails.com ; MODERN ART IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE MODERN ARTISTS: CAI GUO-QIANG, ZENG FANZHI, WANG GUANGYI AND OTHERS factsanddetails.com ; AI WEI WEI: HIS LIFE, ART AND POLITICAL ACTIVITIES factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE SHOCK ART, BODY PARTS, PHOTOGRAPHERS AND VIDEO AND GRAFFITI ARTISTS factsanddetails.com ; LOOTING CHINESE ART AND ARTIFACTS AND TRYING TO GET THEM BACK factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE ART MARKET: COLLECTORS, AUCTIONS, HISTORY, PROFITS AND BRIBERY factsanddetails.com ; FORGING, BREAKING AND COPYING CHINESE ART factsanddetails.com ; HIGH PRICES PAID FOR CHINESE ART factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Art Scene China Art Scene China ; Artron en.artron.net ; Saatchi Gallery saatchi-gallery.co.uk ; Graphic Arts washington.edu ; Yishu Journal yishujournal.com ; Asia Society asiasociety.org ; Art in Beijing Factory 798 in Beijing Wikipedia Wikipedia; Communist China Posters Landsberger Posters ; More Posters chinaposters.org ; More Posters still Ann Tompkins and Lincoln Cushing Collection ; Chinese Modern Artists Cai Guo Qiang.com caiguoqiang.com Guggenheim Show guggenheim.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Zhang Xiaogang Saatchi Gallery saatchi-gallery.co.uk Wikipedia article ; Wikipedia ; Various works artnet.de ; Yue Minjun Works artnet.com

Communist China Posters Landsberger Posters ; More Posters chinaposters.org ; More Posters still Ann Tompkins and Lincoln Cushing Collection

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Chinese Propaganda Posters” by Anchee Min and Stefan R. Landsberger Amazon.com; “Cultural Revolution and Revolutionary Culture” by Alessandro Russo Amazon.com; “The Art of Resistance: Painting by Candlelight in Mao's China” by Shelley Drake Hawks Amazon.com; “Art Mao: The Big Little Red Book of Maoist Art Since 1949" by Pia Copper and Francesca Dal Lago Amazon.com; “The Art of Modern China” by Julia F. Andrews and Kuiyi Shen Amazon.com; “From Mao's Art Soldier to Xi’s Cartoonist: Political Cartoons” by Shaomin Li Amazon.com “Mao Zedong’s “Talks at the Yan’an Conference on Literature and Art”: A Translation of the 1943 Text with Commentary” (Michigan Monographs in Chinese Studies) by Bonnie S. McDougall and Zedong Mao Amazon.com

Socialist Realism

During his rule Stalin sanctioned a form of state art officially known as Socialist Realism. "Geared to a naive, not to say brutish mass public barely literate in artistic matters," wrote TIME art critic Robert Hughes, “Soviet Socialist realism was the most coarsely idealistic kind of art ever foisted on a modern audience."

Social Realism has been defined as "concrete representation of reality in its revolutionary development...in accordance with...ideological training of workers on the spirit of Socialism." It appeared on paintings hoisted in public and on posters splashed all over cities Subjects in the works including spirited workers, heroic soldiers, uplifting leaders. Posters of "shock workers" (people who worked tirelessly for Socialism) show handsome, muscular men with smile son their faces performing some kind of menial chore in front of glistening factories.

Approved Soviet-era culture was dominated by Socialist Realism. One man who lived through the Stalin era told the New York Times, "Art back then was only a reflection of beautiful dream—not of the slave labor of collective farmers or those who dug the canals, mines and built factories than in the long destroyed or Russian land."

See Separate Article SOVIET-ERA ART factsanddetails.com

Chinese Social Realism

In the 1950s, the Soviet art education system was officially taken as the model for art academies in China, and Socialist Realism was chosen as the preferred artistic style. Artists were put to use in the Land Reform campaign, which lead to their ideological transformation and produced guohua (traditional Chinese painting) that aimed to serve the needs of the people in a socialist society. The close connection between art and the reeducation of the artist is evidenced by the 23,000 kilometers sketching tour taken by the Jiangsu Provincial Paining Academy in 1960. Paintings exhibited by members of the Academy in 1958 had been judged too removed from the lived experience of what they were depicting, so the long sketching tour was undertaken to increase the painters’ lived experience of the new China outside the Academy. [Source: Sonja Kelley Dissertation Reviews, February 9, 2016; a review of “Drawing from Life: Mass Sketching and the Formation of Socialist Realist Guohua in the Early People’s Republic of China (1949-1965), by Christine I. Ho]

Social Realism dominated the Mao era and the Cultural Revolution. It appeared on paintings hoisted in public squares and on posters splashed all over cities and villages. Social Realism has been defined as "concrete representation of reality in its revolutionary development...in accordance with...ideological training of workers on the spirit of Socialism." Subjects in the works including spirited workers, heroic soldiers, uplifting leaders. Posters of "shock workers" (people who worked tirelessly for Socialism) showed handsome, muscular men with smiles on their faces performing some kind of menial chore in front of glistening factories.

TIME art critic Robert Hughes wrote: ‘socialist realism was the most coarsely idealistic kind of art ever foisted on a modern audience." It was "geared to a naive, not to say brutish mass public barely literate in artistic matters.” One man who lived through the tough times in the 1940s and 50s told the New York Times, "Art back then was only a reflection of beautiful dream---not of the slave labor of collective farmers or those who dug the canals, mines and built factories.”

A typical Social Realism painting from the Cultural Revolution shows Red Guards on horseback looking across a plain in Inner Mongolia as workers labor to build an aqueduct and miners set off sparks in a black shaft.Social Realism kitsch is very much in demand today. An auction house in Beijing has sold masterpieces of the genre like “People's Apples” for $17,000 and “Chairman Mao is the Red Sun in the Heart of the Revolution” for $37,000. Posters of the latter used to hang on hundreds of factory walls and appeared on millions of postage stamps.

Mao Portraits and Sculptures

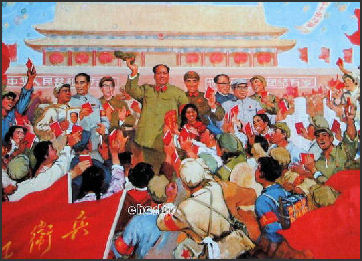

Art in the Mao era was dominated by Mao portraits and propaganda posters showing a smiling Mao standing before happy peasants and factory workers. One painter told the Los Angeles Times, “Mao’s face must be painted extra red to show his robust spirit. It can not be too yellow, which would seem sickly, like he hadn’t eaten for days. You could be accused of being a counterrevolutionary.”

Painters of Mao portraits and other Communist art were not allowed to put their names in their works. A painter of Mao portraits told the Los Angeles Times, “We were told not to think of ourselves as artists. That’s a stinky idea of the bourgeoisie. We are “art workers.”

Mao portrait painters often created their works from simple black and white photographs of Mao. During the Mao era they were kept busy around the clock with orders from all over China. When the Deng reforms kicked they often went weeks without anything to do and made ends meet by doing advertising work.

Mao's portrait hung in practically every shop, every house and every major public area in China. According to one government statistic there were 700 million portraits of Chairman Mao hanging on Chinese walls at the time of his death in 1976. That number was close to the population of China at the time of Mao's death.

Most Mao statues feature the leader waving to the people or standing impressively dressed in an overcoat. Other poses are relatively rare.

Mao Portrait in Tiananmen Square

The portrait of Mao that hangs over Tiananmen Square stands nearly three stories high and is regarded as more than a painting. It is considered a representation Mao himself and an object of adoration and worship. The portrait first hung in 1949 showed Mao wearing an octagonal army hat and course uniform. The next year he appeared without the hat in a Mao jacket. The image today is basically unchanged from the one in 1950. In May 2007, a 35-year-old unemployed man from Xinjiang hurled a burning object at the portrait and damaged it. Authorities cleared Tiananmen Square and the man was arrested.

Exposure to weather damages the Tiananman Square Mao portrait. Every year, usually in the middle of the night in late September, the portrait is taken down and replaced. Two paintings are used. The one that is taken down is fixed up or painted over in a workshop in a quiet corner of the Forbidden City, encased in metal for protection and prepared for the next year. The name of the painter who makes the portrait is a carefully guarded secrecy.

The spirit of Mao era art remains alive among some artists working today. The sculptor Wang Wenhai wants to glorify the Long March with a 426-foot-tall statue of Mao in Yenan, the final destination of the Long March, and place 25,000 small statues of Mao along the 6,000-mile Long March route. The performance artist Qin Ga is retracing the Long Match route with a map of the route tatooed on his back.

Red Art Collections and Exhibitions

Liu Debao is known in China as "The Red Collector". His private collection of materials from the Mao era (1949-1976) includes thousands of posters, films, newspapers and other media materials. Liu has a strong revolutionary and patriotic lineage. His mother was an anti-Japanese guerilla fighter. Born in 1951, he was 15 when the Cultural Revolution broke out, and became a Red Guard. He has been collecting since 1968 and sometimes present some of collection at film festivals.

In the summer of 2011,to mark the 90th anniversary of the Communist Party of China, there were three red art exhibitions running simultaneously at Beijing's major museums: the National Museum of China, the National Art Museum of China and the Military Museum of the Chinese People's Revolution. "We are trying to turn a politically charged art exhibition into a visual feast that is also thought-provoking,"National Art Museum director Fan Di'an said [Source: Zhu Linyong, China Daily July 2, 2011]

The National Art Museum teamed up with more than 10 provincial and municipal museums and galleries to stage Glorious Path, Grand Picture, a comprehensive art show featuring more than 300 ink works, oil paintings, watercolors, sculptures, woodblock prints, New Year pictures and picture-story books created between 1938 and 2011. Divided into three parts, the exhibition illustrates: 1) the rise of the Communist Party of China (CPC) between 1921 and 1949, 2) the trying and eventful years between 1949 and 1978, and 3) the new era since China's opening-up and reform spearheaded by CPC leaders, such as Deng Xiaoping.

To mark the 90th anniversary of the Communist Party of China over 1,000 artists from across the country were recruited to make new works inspired by China’s revolutionary period in a Ministry-of-Culture-sponsored program valued at about 100 million yuan ($15.47 million), according to the Ministry of Culture. Many artists have paid visits to sites associated with the CPC's early history to gain inspiration. They included Jinggang Mountain in Jiangxi province, where Mao Zedong formed the Red Army; and Xibaipo in Hebei province, where CPC leaders, such as Mao and Zhu De, guided the People's Liberation Army in major battles against the Kuomintang army from 1947 to 1949. "It's like a pilgrimage to the mecca of Chinese revolution," recalls Li Qingke, an artist from Sichuan province who visited a string of revolutionary sites in Hunan province before creating his ink work Long March. "Through field study, I have readjusted my viewpoint of Chinese revolutionary history and feel connected to its traditions," he said.

Red Art from the Period of Rise of the Communist Party of China between 1921 and 1949

penetrate the countryside Among the best-known works from rise of the Communist Party of China (CPC) between 1921 and 1949 are Autumn Harvest Uprising, Torches in Yan'an, marble relief pieces for the Monument to People's Heroes, the best-selling picture-story book Red Ribbon on the Earth, stone sculpture Hard Times and ink portrait Premier Zhou Enlai and the People. [Source: Zhu Linyong, China Daily July 2, 2011]

Other eye-catching showpieces include oil portraits of American journalist Edgar Snow (1905-1972), who made the earliest exclusive interview of Chinese leader Mao Zedong in 1936; Canadian Norman Bethune (1890-1939) who fought against Japanese invaders along with the Eighth Route Army in North China; and a woodblock print that depicts illiterate peasants in Yan'an, Shaanxi province, attending a democratic election using beans as votes.

“The New Woodcut Movement of the 1930s and 40s was begun by the writer and scholar Lu Xun. Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Although initially trained as a doctor, Lu Xun came to believe that the plight of the Chinese masses could be improved only through the widespread dissemination of socially aware art and literature. In the woodblock print, especially as developed by the German Expressionists, Lu Xun saw an effective tool for exposing the social ills of China. Artists influenced by Lu Xun focused on the inequities suffered by the lower classes. Due in part to this redirection in subject matter, the woodcut medium was perceived to be Western and modern although woodblock printing had been invented in China and had been widely used since the Tang dynasty. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

“From the time of the May Fourth protests in 1919, Japan was seen as the greatest threat to China's sovereignty. By the 1930s Japan had taken over most of Manchuria and set up a puppet state there. In 1932 the Japanese attacked Shanghai directly to retaliate against anti-Japanese protests. Anger at Japanese aggression heightened Chinese nationalism. In the woodcuts of this period patriotic young artists called for resistance to the invaders and criticized the Nationalist government for not taking decisive action.

“Although Lu Xun was never an official member of the Communist Party, his emphasis on the exploitation of peasants and the working class fit well with the revolutionary message of the CCP. In 1937, after Lu Xun's death, the Lu Xun Academy of Arts was established at the Communist base of Yan’an to instruct artists in the art of propaganda. Woodblock prints were particularly suited for this purpose because they were relatively cheap and easy to copy. By the 1940s there were artists traveling through the countryside distributing prints with ideological messages.

“Committed to a more egalitarian social and economic order, Mao Zedong and other leaders of the Communist Party set about fashioning a new China, one that would empower peasants and workers and limit the influence of landlords, capitalists, intellectuals, and foreigners. Spreading these ideas was the mission of the propaganda departments and teams. Political posters, reproduced from paintings, woodcuts, and other media, were displayed prominently in classrooms, offices, and homes. The artists who produced these works had to follow the guidelines set by Mao Zedong at the 1942 Yanan Forum for Literature and Art. Art was to serve politics and further the revolutionary cause. Toward that end, it must be appealing and accessible to the masses. Artists, previously fairly independent from politics, were now a key component in the revolutionary machine. “Cultural workers” were sent out to villages and factories to study folk art and learn from real life. In addition, workers and peasants were encouraged to attend art schools and create artwork of their own.

Red Art from the Revolutionary Period Between 1949 and 1978

Subjects of works from the Revolutionary Period Between 1949 and 1978 include CPC founders, such as Li Dazhao, Mao Zedong, Zhu De and Zhou Enlai, war heroes and heroines, and ordinary Chinese who fought for freedom and democracy in the first half of the 20th century. Portrayals of revolutionary figures are often larger than life and look like gods instead of humans. They are rendered with exaggerated bright red tones to express their enthusiasm for revolution and hopes for a better society. [Source: Zhu Linyong, China Daily July 2, 2011]

Some artists were forced to change the original versions of their works for political reasons. In 1953, master oil painter Dong Xiwen (1932-1973) created a grand work depicting the moment when Mao Zedong declared the founding of the People's Republic on Oct 1, 1949, on the Tian'anmen Rostrum. He was told to erase former Chinese leader Gao Gang from the painting in 1954 and to take out former Chinese leader Liu Shaoqi from the work in 1972, during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). The work regained its original look only in 1979 when CPC leaders led Chinese people into a new era of opening-up and reform, and began taking a more liberal and tolerant approach to artistic creations.

"These red art classics have become an integral part of our history and are sources of strength and inspiration for people today," says Wang Yanni, daughter of master painter Wang Shikuo (1911-1973). In her view, the older generations of artists, including her father, "were expressing in their works their heartfelt appreciation and admiration of the New China led by the CPC".

To create the critically acclaimed Blood Stained Clothes - a huge pencil drawing that depicts a scene during the land reform process in the 1940s - her father made countless field research trips to rural areas. He produced 370,000 sketches of peasants from 1950 to 1953. The hardworking artist died of a heart attack when doing a sketch of a peasant in 1973, in Gongxian county, Henan province. The sketch was for an oil version of his masterpiece Blood Stained Clothes, commissioned in 1972 by the National Museum of Chinese Revolutionary History (now known as the National Museum of China).

In a review of “The Making and Remaking of China’s “Red Classics”, Yizhong Gu wrote: In chapter 5, Kuiyi Shen examines the incorporation of revolutionary themes into China’s indigenous form of painting, guohua . Fifteen exquisitely printed color inserts of guohua allow Shen to deftly guide readers through his analysis of each painting’s composition and texture while providing relevant details of the painters’ lives and perspectives. Shen concludes that revolutionary content gave rise to creativity for these enthusiastic socialist painters, who “successfully created a new kind of art,” the “new guohua,” whose aesthetic vocabulary still dominated the Chinese art world in the 1980s and 1990s. [Source: Book:“The Making and Remaking of China’s “Red Classics: Politics, Aesthetics and Mass Culture” edited by Rosemary Roberts and Li Li (Hong Kong University Press, 2018; [Source: Yizhong Gu, University of Washington, MCLC Resource Center Publication, May, 2018)

Maoist Art in the 1950s and 60s

“The Rent Collection Courtyard” was a revolutionary landmark Chinese installation work. In 1965, a group of sculptors from the Sichuan Institute of Fine Arts created 114 life-size clay figures depicting starving peasant farmers bringing their rent to a tyrannical feudal landlord’s residence, a trenchant Communist critique of practices of serfdom and servitude in imperial China. After the groundbreaking installation at a landlord’s former residence in China, the figures were reproduced in a unique maquette (scale model) which belongs to USC Pacific Asia Museum. [Source: “The Changing Exhibition Galleries: South Gallery Asia Pacific Museum University of Southern California September 26, 2014 through February 22, 2015]

In a review of the book “Visual Culture in Contemporary China: Paradigms and Shifts” by Xiaobing Tang, Wendy Larson wrote: “One idea Tang attacks is the common notion that culture is determined by politics, arguing that it is more revealing to see politics as a response to cultural issues. His primary point — that the socialist revolution aimed at substantial and profound cultural transformation — is important, and often is overlooked as the excesses of ideology take center stage. The first step in cultural change is the transformation of the artist through his or her own efforts, as woodcut artist Jiang Feng reported at the All-China Congress of Literary and Art Workers in 1949. This realigning of subjectivity was aimed at learning how to value and create art for the majority of people rather than for aesthetic connoisseurs, and involved the negotiation between revolutionary ideas and indigenous practices. One important movement revolved around the popular nianhua, or New Year’s prints, which melded art and politics. A robust conversation about the value and decline of woodcut prints, led by printmaker Li Qun and others, faulted the field for not keeping up with society, duplicating Western forms, and failing to create a unique Chinese character. [Source: Wendy Larson, University of Oregon, MCLC Resource Center, August, 2016. Book: “Visual Culture in Contemporary China: Paradigms and Shifts” by Xiaobing Tang. (Cambridge University Press, 2015)]

Overall, the early 1950s was characterized by passionate intellectual argumentation about the way to bring a socialist vision to visual arts, and about the relationship between art and life. One fascinating controversy focused on Liang Yongtai’s 1954 woodcut print Where No One Has Been Before. In a heavily romanticized rendition, Liang depicted the K-shaped Faux Namti Bridge, which was built by the French Batignolles Construction Company in 1908. The gorge in Liang’s print is full of wildlife and lush plants growing in an alluring valley, which Li Hua criticized as a failure to follow the principles of socialist realism. Others disagreed, pointing to the need for a range of visions.

“Chapter 2 emphasizes painting, with an extended analysis of Wang Shikuo’s The Bloodstained Shirt (1959), a detailed charcoal sketch that was a study for an oil painting. The drawing evokes the new and powerful subject position for Chinese peasants, who took on a heroic role in the collective struggle on land reform. Tang does an excellent job teasing out the complexity of the painting, skillfully weaving in and out of the social debates of the times. The piece revolves around the passionate public “speaking bitterness,” in which peasants were encouraged to speak out about their suffering and fear under the violence and power of landlords. As Tang explains, this act was crucial in the formation of a new symbolic order in which peasants became the agents of history. The need to produce a moving but unambiguous depiction brought some anxiety to the painter, who termed his methodology gaikuo, or the inducing and summarizing of the specific characteristics of an event or phenomenon. The centering of the bloody shirt in the middle of the painting provided forensic evidence of the landlord’s ruthlessness. Before completing the painting in 1959, Wang created a number of studies that considered options for all parts of the work, carefully considering the possibilities and their significance. Many of these fascinating drawings are included as images in the book. The notion of the typical character — developed in the Soviet Union and influential in Chinese literature from the 1930s on — for Wang was a powerful concept that helped him create lifelike characters. Again, the crux of the socialist vision was to bring historical agency to those to whom it had been denied.

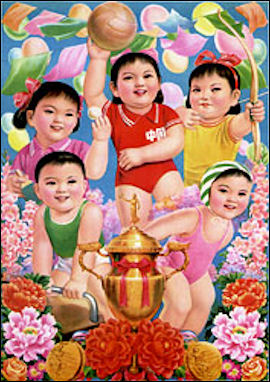

Mao-Era Posters

A typical Mao-era poster was titled "Every Generation Is Red." Perhaps because of the importance of children for the future of the socialist state, they were often pictured in political posters. The typical oil painting was entitled "Chairman Mao Has Come to Our Factory." Slogan hung from the roofs of shops read "March Down Chairman Mao's Revolutionary Road."

In a review of the book “Red Legacies in China, Xing Fan wrote: “In Chapter 3, “Ambiguities of Address,” Harriet Evans challenges the reader to see beyond the face value of propaganda posters. She points to negotiated readings to account for the enduring appeal of Cultural Revolution posters, arguing that the appeal and understanding of these posters are far from consistent or unitary across time and place. [Source: Book “Red Legacies in China: Cultural Afterlives of the Communist Revolution” (Harvard University Asia Center, 2016), edited by Jie Li and Enhua Zhang. Xing Fan, Review, MCLC Resource Center Publication, March, 2017]

Evans presents the perplexing picture from four perspectives: poster imagery which — whether or not featuring Mao’s iconic figure — evokes different emotions and motivations from readers in different times; the fluid relationship between posters and their painters (involving, among other aspects, personal interests, private fantasies, artistic skills, and aesthetic choices); images of women that give rise to a variety of readings in different genders and generations; and the re-reproduction of Cultural Revolution posters, with their various themes appealing to diverse viewers in different temporalities, intricately associated with contemporary consumers’ ever-changing, mixed feelings regarding the past, the present, and the future. [Source: Book “Red Legacies in China: Cultural Afterlives of the Communist Revolution” (Harvard University Asia Center, 2016), edited by Jie Li and Enhua Zhang. Xing Fan, Review, MCLC Resource Center Publication, March, 2017]

Big Characters Posters (Dazibao) and Cultural Revolution Art

Big Characters Posters were used in the Cultural Revolution to publicize events, express views and carry out debates. It can be argued that the Cultural Revolution began with them. On May 25, 1966, according to Associated Press, "Big character" posters denouncing all those who would oppose Mao and his revolution begin appearing, opening the flood gates to mass political movements at college campuses throughout the country. Soon after, classes in schools nationwide are suspended indefinitely. \^

On an exhibition of such posters at Harvard, Michael Szonyi of Harvard’s Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies wrote: During the Cultural Revolution “big character posters” (dazibao ), were large, hand-written signs pasted on walls throughout China. Their content criticized local officials, colleagues, teachers, bosses, co-workers, former friends—virtually no one was exempt—for a wide-range of supposed political transgressions in what often became a cycle of high-stakes political attacks and counter-attacks.

“Despite the important role dazibao played in the visual and political landscape of the Cultural Revolution – as well as the subsequent Democracy Wall movement – they were never intended to be permanent, and so the vast majority were destroyed or simply decayed. Many China scholars, even experts on the period, have never had the chance to view dazibao up close. The creation of huge numbers of dazibao at this particular moment in China’s history can also be understood as an aesthetic or artistic phenomenon. Though only a scintilla of these works survive, dazibao occupy an important position in Chinese art history. Their reflection of the previous artistic tradition and their continuing inspiration for contemporary artists makes them perhaps as valuable to the art historian as to the student of politics.”

See Separate Article CULTURAL REVOLUTION CULTURE: OPERAS, MANGOES AND THE LITTLE RED BOOK factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: 1) Mao and pre-Mao images: University of Washington

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021