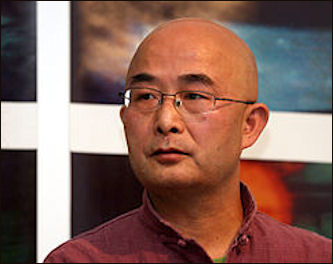

LIAO YIWU

Liao Yiwu is an outspoken writer, poet, , novelist, oral historian, and musician who went to prison for four years after writing a strongly-worded poem called “Massacre” about the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown. [Source: Keith Bradsher, New York Times, May 9, 2011]

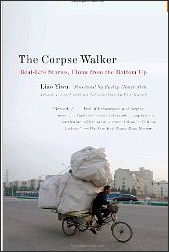

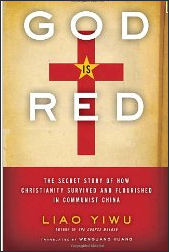

Liao (pronounced lee-YOW) remains one of China's most outspoken writers. Banned in mainland China, his works have been published abroad in translation, including “The Corpse Walker: Real Life Stories, China from the Bottom Up” (2008), which has received overwhelmingly positive reviews and describes people at the margins of life in China, including a professional funeral mourner and a grave robber, and “For a Song and a Hundred Songs: A Poet’s Journey Through a Chinese Prison (2013)”, about his four years in Chinese prisons. His work is especially popular in Germany, where he lives. Liao went on a U.S. book tour to promote his new book, “God is Red: The Secret Story of How Christianity Survived in the Communist China” (2011). Liao received a Freedom to Write Award from the Independent Chinese PEN Centre in 2007. While he was in China he was constantly harassed by the Chinese government.

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Times, “For years, Liao’s work, which draws on extensive interviews with ordinary Chinese, has been banned by the authorities for its provocative revelations about everyday life. In early July, amid a worsening atmosphere for artists and intellectuals critical of the Chinese government, Liao fled to Germany via a small border crossing to Vietnam in Yunnan province. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Times August 15, 2011]

Liao first came to prominence in 1989 when he recorded an extended stream-of-consciousness protest poem called “Massacre” about the Tiananmen Square crackdown. He was subsequently arrested and spent four years in prison, where he met the series of outcasts and misfits who became the protagonists of his first book on China’s underclass. Written in the form of questions and answers, these stories became symbolic vignettes about people from a range of offbeat and unusual professions or situations. Some of them were translated in The Paris Review in 2005, and they were collected and expanded in the 2008 book “The Corpse Walker: Real Life Stories, China From the Bottom Up”.

Liao is renowned for his straightforward approach to his subjects, his quiet humour and courage. The novelist Salman Rushdie called him one of "the few people who are the real writers" around the world. At a PEN gathering in New York Liao played traditional Chinese instruments and gave an intense recitation of "Massacre." [Source: AFP, South China Morning Post September 14, 2011]

See Separate Articles: CULTURE AND LITERATURE factsanddetails.com; CONTEMPORARY CHINESE LITERATURE factsanddetails.com ; JIN YONG AND CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FICTION factsanddetails.com ; LITERATURE AND WRITERS DURING THE MAO ERA factsanddetails.com CULTURAL REVOLUTION FILM AND BOOKS factsanddetails.com ; ACCLAIMED MODERN CHINESE WRITERS factsanddetails.com ; MO YAN: CHINA'S NOBEL-PRIZE-WINNING AUTHOR factsanddetails.com YU HUA factsanddetails.com ; YAN LIANKE factsanddetails.com ; WANG MENG factsanddetails.com ; POPULAR MODERN CHINESE WRITERS factsanddetails.com ; POPULAR AND ACCLAIMED BOOKS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SCIENCE FICTION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE SCIENCE FICTION WRITERS factsanddetails.com ; MODERN POETRY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; WRITERS OF CHINESE DESCENT: AMY TAM, HA JIN, YIYUN LI AND GAO XINGJIAN factsanddetails.com ; PUBLISHING TRENDS AND MODERN BOOK MARKET IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; INTERNET LITERATURE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; POPULAR WESTERN BOOKS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; WESTERN BOOKS ABOUT CHINA factsanddetails.com ;

Modern Chinese Writers and Literature: MCLC Resource Center mclc.osu.edu ; Modern Chinese literature in translation Paper Republic paper-republic.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Corpse Walker: Real Life Stories: China From the Bottom Up” by Liao Yiwu Amazon.com; “Bullets and Opium: Real-Life Stories of China After the Tiananmen Square Massacre by Liao Yiwu, Francois Chau, et al. Amazon.com; “God Is Red: The Secret Story of How Christianity Survived and Flourished in Communist China” by Liao Yiwu and Wen Huang Amazon.com; “For a Song and a Hundred Songs: A Poet's Journey through a Chinese Prison” by Liao Yiwu and Wenguang Huang Amazon.com; “Wuhan: A Documentary Novel” by Liao Yiwu and Michael M Day Amazon.com; Amazon.com

Liao Yiwu’s Life

Howard W. French wrote in The Nation: “Liao Yiwu was born in Sichuan Province in 1958. At the outset of the Cultural Revolution, in 1966, his late father, a small landlord, was jailed as a “class enemy.” In fact, the family had been targeted for persecution since 1959 when his mother, a music teacher, was fired from her primary school job for “bourgeois thinking.” After being caught trading ration coupons for food, Liao's mother ran away with her son and a younger sister to Chengdu, Sichuan's big provincial capital, where they lived a precarious life without a residence permit. Liao left home two years later, at age 10, hoping to find his father and eventually making a living through a succession of small hard-knock jobs, hauling rocks or rolling cigarettes. In the early 1970s, his father was released from jail and allowed to teach at a rural middle school. Schools had been closed throughout the country amid the political chaos, and Liao, already in his early teens, went to primary school in the same town where his father worked.” [Source: Howard W. French, The Nation, August 4, 2008]

Liao told an audience in Taiwan: “My father made me stand on a table when I was small, and recite ancient classical Chinese. I could only climb down after I was able to recite the whole thing by heart. I was only 3 or four years old, maybe. I hated my father.”This is how Liao Yiwu began to talk to the students and teachers of National Ch'engkung University in Tainan, after he played a wooden flute, a very basic instrument he had learned in prison. Very basic sounds, mute and suppressed at times. Loss and regret. No uplifting fable. “I am not going to tell you very much about the time when I went into prison. You would have no way to understand everything. I was like any young person. I didn't want to listen to anybody from older generations. And I had gone through the Cultural Revolution, when my parents couldn't take care of me. For me, classical Chinese belonged into the rubbish bin, along with many other things. My father was 84 years old when he died?, Liao Yiwu said. Or was it 88 years? Only a few hours of dialogue and open exchange between father and son, in all those years.

Ian Buruma wrote in The New Yorker: Liao “led a rather dissolute life, wandering from place to place as a “well-dressed hypocrite, a poet who portrayed himself as a positive role model but all the while breathed in women like I was breathing air, seeking shelter and warmth in random sex.” Like many Chinese who grew up during the Cultural Revolution, Liao was more or less self-educated in literature, although he received a grounding in the Chinese classics from his father, a schoolteacher. His memoir is sprinkled with the names of Western writers — Orwell, Kundera, Proust — some of whose works penetrated even the prison walls in Chongqing. Among them, amazingly, was Orwell’s “Nineteen Eighty-Four.” In Liao’s words, “On the page was an imaginary prison, while all around me was the real thing.” [Source: Ian Buruma, The New Yorker, July 1, 2013]

In 1982 Liao's first poem, “Dawn,” appeared in Xing Xing, an influential poetry journal, winning him wide attention. By 1988 Liao had just turned 30, and his poems had already won him a national reputation, along with twenty poetry prizes and awards. When the Chinese army violently put down the student-led protests at Tiananmen Square, Liao wrote an epic poem, which he titled “Massacre.” Knowing it could not be published in the country, he recorded it on cassette, giving a tape to a friend and allowing it to be copied and passed along from person to person. Word of the poem spread fast, leading to the author's arrest, and in March 1990 Liao was imprisoned and spent the next four years locked up.” See Prison Book Below

Christen Cornell wrote in ArtSpace China," Given his reputation as a political dissident, it would be fair to imagine Liao Yiwu as a terribly earnest person. If he is this, it doesn’t come across in a first meeting...More than anything, Liao made us laugh with his dry irreverence, and a tendency to see life as a series of terrific stories. Even the sinister seemed darkly amusing in Liao’s hands, as if life were a perverse comedy choreographed by money and power." [Source: Christen Cornell ArtSpace China, November 29, 2011]

Liao Yiwu’s Life After Prison

In the years after I came out of prison I had no way to make a living. I had to find a way to get by, so I started to play music for small change. I played in bars for two years or more — pop, folk, love songs, easy listening. There’d usually be a few set songs that the boss would get you to play and then the rest was up to the audience and their requests. I played the Chinese flute, the xiao, and sometimes sang. Sometimes I used the xiao to turn folk into rock and roll. [Source: Christen Cornell ArtSpace China, November 29, 2011]

I remember some pretty funny things from that time. Like during the wee hours, maybe 3am or 4am, there would usually be some people left in the bar: depressed people, those with broken hearts, alcoholics with no home to go to. They’d all hang around the bar, drinking, drinking, drinking. And that was when I’d usually start to make some money. The bar would be almost empty — just two or three sad sacks with their drinks — but the sound of the xiao was so melancholy it made these people think of their boyfriend or whoever? They’d call you over to play and I’d put on a real show of sympathising with them. In those days a song might normally get 10 kuai, but at that hour I could get 30 kuai! [laughs]

This was in the 1990s, after I got out of prison. In Chengdu, mostly, sometimes Beijing. I was just floating around, spending my time with people on the fringes of society. If I made enough money one night I might not work for the next two or three; I’d only go back to play again when I’d run out of money. In those days I was just living in the moment, never thinking about my next step. I never saved any money. Eventually, though, I decided I should pick up my old professional writing again, that I should publish and sell some books. All I knew was the stories of these underground people, and the people I had met in prison, so I started to recall them and write them down.

Liao Yiwu’s Efforts to Get Out of China

In April and May 2011 Liao was refused permission to visit literary festivals in New York and Australia and was the subject of a protest led by Salman Rushdie, criticized the travel prohibition as, “an extremely unfortunate statement on the part of Chinese authorities about its willingness to engage in free and open cultural exchange.” Liao had earlier been denied permission to visit Germany but was eventually allowed to go. After that run in he said, “I never considered myself to be a political dissident.” [Source: Keith Bradsher, New York Times, May 9, 2011]

Liao said that he had been denied permission 14 times to leave China from 1999 until last autumn, when he received permission to travel to Germany after literary acclaim for “The Corpse Walker”. “While I was in Germany, my friends suggested that I stay in Germany and not return to China with all the restrictions, but I told them I wanted to return to China since I write about China,” he told the New York Times, expressing no regrets about this decision.

The dissident writer Liao Yiwu wrote in the New York Times, “Yunnan Province, in southwestern China, has long been the exit point for Chinese who yearn for a new life outside the country. There, one can sneak out of China by land, passing through pristine forests, or one can go by water, floating all the way down the Lancang River until it becomes the Mekong, which meanders into Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam.[Source: Liao Yiwu, New York Times, September 1, 2011, Liao Yiwu is the author of “God Is Red” and “The Corpse Walker.” This essay was translated by Wen Huang from the Chinese.]

So each time I set foot there, in a land where red soil gleams in the sun, I turned restless; my imagination ran wild. After all, having been imprisoned for four years after I wrote a poem that condemned the Chinese government’s brutal suppression of student protesters in 1989, I had been denied permission to leave China 16 times. I felt very tempted. It doesn’t matter if you have a passport or visa. All that counts is the amount of cash in your pocket. You toss your cellphone, cut off communications with the outside world and sneak into a village, where you can easily locate a peasant or a smuggler willing to help you. After settling on the right price, you are led out of China on a secret path that lies beyond the knowledge of humans and ghosts.

Until earlier this year, I had resisted the urge to escape. Instead, I chose to stay in China, continuing to document the lives of those occupying the bottom rung of society. Then, democratic protests swept across the Arab world, and posts began appearing on the Internet calling for similar street protests in China. In February and March, there were peaceful gatherings at busy commercial and tourist centers in dozens of cities every Sunday afternoon. The government panicked, staging a concerted show of force nationwide. Soldiers changed into civilian clothes and patrolled the streets with guns, arresting anyone they deemed suspicious.

In March, my police handlers stationed themselves outside my apartment to monitor my daily activities. “Publishing in the West is a violation of Chinese law,” they told me. “The prison memoir tarnishes the reputation of China’s prison system and “God Is Red” distorts the party’s policy on religion and promotes underground churches.” If I refused to cancel my contract with Western publishers, they said, I’d face legal consequences.

Then an invitation from Salman Rushdie arrived, asking me to attend the PEN World Voices Festival in New York. I immediately contacted the local authorities to apply for permission to leave China, and booked my plane ticket. However, the day before my scheduled departure, a police officer called me to “have tea,” informing me that my request had been denied. If I insisted on going to the airport, the officer told me, they would make me disappear, just like Ai Weiwei.

For a writer, especially one who aspires to bear witness to what is happening in China, freedom of speech and publication mean more than life itself. My good friend, the Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo, has paid a hefty price for his writings and political activism. I did not want to follow his path. I had no intention of going back to prison. I was also unwilling to be treated as a ‘symbol of freedom” by people outside the tall prison walls.

Liao Yiwu Finally Gets Out of China

In July 2011 — after seventeen unsuccessful attempts to leave China — Liao Yiwu secretly emigrated to Germany. Liao said, "Only by escaping this colossal and invisible prison called China could I write and publish freely. I have the responsibility to let the world know about the real China hidden behind the illusion of an economic boom — a China indifferent to ordinary people’s simmering resentment. [Source: Liao Yiwu, New York Times, September 1, 2011, Liao Yiwu is the author of “God Is Red” and “The Corpse Walker.” This essay was translated by Wen Huang from the Chinese.]

“I kept my plan to myself. I didn’t follow my usual routine of asking my police handlers for permission. Instead, I packed some clothes, my Chinese flute, a Tibetan singing bowl and two of my prized books, “The Records of the Grand Historian” and the “I Ching.” Then I left home while the police were not watching, and traveled to Yunnan. Even though it was sweltering there, I felt like a rat in winter, lying still to save my energy. I spent most of my time with street people. I knew that if I dug around, I could eventually find an exit.”

“With my passport and valid visas from Germany, the United States and Vietnam, I began to move. I shut off my cellphone after making brief contacts with my friends in the West, who had collaborated on the plan. Several days later, I reached a small border town, where I could see Vietnam across a fast-flowing river. My local helper said I could pay someone to secretly ferry me across, but I declined. I had a valid passport. I chose to leave through the border checkpoint on the bridge.”

Before the escape, my helper had put me up at a hotel near the border. Amid intermittent showers, I floated in and out of dreams and awoke nervously to the sound of a knock on the door, only to see a prostitute shivering in the rain and asking for shelter. Although sympathetic, I was in no position to help.”

At 10 a.m. on July 2, I walked 100 yards to the border post, fully prepared for the worst, but a miracle occurred. The officer checked my papers, stared at me momentarily and then stamped my passport. Without stopping, I traveled to Hanoi and boarded a flight to Poland and then to Germany. As I walked out of Tegel airport in Berlin on the morning of July 6, my German editor, Peter Sillem, greeted me. “My God, my God,” he exclaimed. He was deeply moved and could not believe that I was actually in Germany. Outside the airport, the air was fresh and I felt free.

After I settled in, I called my family and girlfriend, who were questioned by the authorities. News about my escape spread fast. A painter friend told me that he had gone to visit Ai Weiwei, who is still closely watched. When my friend mentioned that I had mysteriously landed in Germany, Old Ai’s eyes widened. He howled with disbelief, “Really? Really? Really??

When people asked him how he fled from China "It was very simple", Liao Yiwu said. "I went to Yunnan province, bordering Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar and Tibet. I had made lots of interviews there many years before, with people at the bottom of society. You turn off your mobile. You could also bring extra mobile phones. You get lost in small towns. And then one day I was across the border in Vietnam, very wobbly on my legs. There was a small train, like in China at the beginning of the 1980s. I knew such trains from drifting around China when I was young. In Vietnam, I was afraid of a lot of things, getting on the train, of simple things to eat. But I could communicate by writing numbers on a piece of paper. 500, wrote the innkeeper. 100, I wrote below. And so on. Finally I was in Hanoi, in a simple inn. And then I went on-line and contacted my friends and family in China. When I got on the plane to Poland, I was still afraid. The year before, military police in full military gear had come and taken me out of the plane in Chengdu. But then I realized, although this was a Socialist country, I was in the capital of another country, not in China. And the plane took off."

Liao Yiwu After Leaving China

On leaving China, Liao told the New York Times, “I never said I wanted to go into exile or flee. It’s just because if I didn’t my books wouldn’t get published. I guess I won’t go back for a while. I’m doing publicity for the prison book now, then I’ll go to the US for my Christianity book. Then Taiwan for the Chinese edition of the prison book. Then back to Germany, where I have a one-year DAAD fellowship in Berlin. So when that’s all over, I’ll see if they haven’t forgotten me. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Times August 15, 2011]

Liao told the New York Times he left China without telling his closest relatives his mother, brother and sister. He said he couldn’t tell them. “I was the only one who knew...Slowly they’ll understand. For example, if I’m arrested they have to deliver food to me in prison — it’s a burden for them [laughing]. All those trips to the prison [laughs]. I’ve spared them those trips.” Does your mother understand what you do, your writing? She does, but she wishes I wasn’t mixed up in politics. But I’m not. I’m not interested in politics. I’m not like Liu Xiaobo. I didn’t write a Charter 08 I did sign it. The police asked me why I signed it and I said I don’t know, I just felt like it.

Liao told The New Yorker, “In 2012, the leadership will change in Beijing, and I’m looking forward to a new government with the hope that I may then go back to China...It was like magic that I was able to get out, and such wonderful magic that I even got an exit stamp in my passport.” So he is not a refugee. “Never, I’m excited about political developments in China, and looking forward to a Jasmine Revolution. I am quite sure that Hu Jintao may be a refugee some day, but not Liao Yiwu.” [Source: Philip Gourevitch, The New Yorker, July 6, 2011]

At a PEN gathering in New York Liao played traditional Chinese instruments and gave an intense recitation of "Massacre." During his three days in New York, Liao said he had been stunned to find a huge immigrant Chinese community in Flushing, an area of Queens. "I’ve never seen so many Chinese," he said to laughter, before describing how he ran into "swindlers" trying to sell fake phones. "It feels like that’s going to be China without communism," he said to more laughter. [Source: AFP, South China Morning Post September 14, 2011]

On Liao’s life in 2013, Elaine Sciolino wrote in the New York Times: He is “at work on his next book, a history of his extended family. He writes in long spurts at night in a modest garden apartment he owns in the comfortable Westend neighborhood of Berlin. It is furnished with a bed, a table, a cooking pot and a teakettle. He confesses that he took German lessons for three months but has given them up and that he spends much of his spare time socializing with other Chinese exiles. On the difference between German prostitutes and Chinese prostitutes, Liao Yiwu said, “The Germans are more polite. If you don’t want to, they leave you alone. In China, several will fight over you. He keeps in touch with his mother and others in China through Skype. Divorced from his Chinese wife, he has spent less than two months with his daughter, now in her 20s. [Source: Elaine Sciolino, New York Times, April 9, 2013]

Liao Yiwu, Politics and Liu Xiaobo

Ian Buruma wrote in The New Yorker:“Liao was not a political activist, or, strictly speaking, a dissident, and his resistance had a spontaneous quality. Politics didn’t interest him much, even during the nineteen-eighties, when many young Chinese thought of little else. Unlike his friend Liu Xiaobo, a Nobel Prize-winning critic and a writer with strong political convictions, Liao never wished to stick his neck out. He describes himself as an artist who simply wanted to be free to write in any way he liked. As recently as 2011, he told the journalist Ian Johnson, “I don’t want to break their laws. I am not interested in them and wish they weren’t interested in me.” But, in 1989, he put himself “on a self-destructive path” by performing his poem in bars and dance clubs, howling and chanting in the traditional manner of Chinese mourning. A recording of the poem was distributed informally, and a film, entitled “Requiem,” was made of his recitation by a group of sympathetic artists and friends. None, according to Liao, could be classified as “dissidents” or “democracy fighters.” But they were all arrested, their work confiscated, and thus “the Public Security Bureau destroyed a vibrant underground literary community in Sichuan.” [Source: Ian Buruma, The New Yorker, July 1, 2013]

“Liao’s time in prison didn’t turn him into an activist, either. He was approached at one point by a fellow-“89er,” who planned to start an organization of political prisoners. Liao refused to take part, and explained the reason for his having written “Massacre” in the first place. He “was compelled to protest,” he said, because “the state ideology conflicted violently with the poet’s right of free expression.” To this, he added in his memoir, “I never intended to be a hero, but in a country where insanity ruled, I had to take a stand. ‘Massacre’ was my art and my art was my protest.”

Liao told Artspace China: A lot of people when they come out of prison decide that they want to start afresh, but I wasn’t like that. After I came out of prison I was just floating. I was friends with Liu Xiaobo. We were extremely old friends — in the 1980s we worked together on some literature projects. He used to write literature, I wrote poetry. These days his wife is also writing poetry — but we all knew each other from that time. So I was writing, and I was playing music, but at the same time Liu Xiaobo was constantly asking me to sign his various petitions, and I signed them out of friendship. He’d send me these petitions by fax and I’d sign them and send them back. The faxes were so blurry sometimes I didn’t even know what I was signing! The police would come asking whether or not I’d done these things. [laughs] And each time they’d detain me for 10-20 days. They’d take me to a guesthouse and ask what I’d been involved in, but most of the time I couldn’t remember. [laughs] They’d often pull out the petitions I’d signed and read them out to me, like an official proclamation. [laughs] [Source: Christen Cornell ArtSpace China, November 29, 2011]

On whether his main drive was political, Liao said, “Other people probably think it was political, but I don’t see it like that at all. I just see it as common sense. I was only saying what everybody already knows. As far as I’m concerned common sense shouldn’t be considered political. If you are afraid to say something then that is political, or you find it difficult to explain something, it might be because it has some political dimension or there’s some kind of pressure on you. And if you find yourself in that situation then you’re not a pure artist. A real artist says what he feels.

When I first started writing about these marginal people it never occurred to me that it would become a problem. I was just writing about suffering and shamelessness, the suffering and shamelessness of Chinese people. When The Corpse Walker was published, it did very well. It was published in more than forty countries — everyone made a big a big fuss and thought it was amazing that someone was writing these stories down. Not long after though: disaster! [laughs] It came from every angle. The government apparatus came bearing down on me, someone who’d never really even thought about politics. Without my ever meaning them to, the stories I’d been working on had become a political act.

Liao Yiwu’s on Writing and Reportage

Liao Yiwu old the New York Times, “The 1980s were a golden age for Chinese thought and literature. Then came 1989. Then came the reforms and the economic growth. No one thought the Communists would be so tough and strong. It’s caused all these waves of immigration. After they took over there was a big wave of immigration as people fled. Then after 1989 there was another wave of about 100,000 who left. Now there’s a new wave of people leaving, even though the economy is so good. At least among many artistic people it’s like this. You can’t do anything meaningful in China. If you return you have three choices: flee, sit in prison or shut up. I had to flee. Liu Xiaobo and Ai Weiwei weren’t able to flee but I was. It’s probably because I interviewed a lot of these underclass people so I understand how the police think. That allowed me to figure a way out. I have contacts in the underground. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Times August 15, 2011]

I’d like to publish in China but since 2001 I haven’t been able to. In the 1990s it was difficult but then after 2001 nothing at all. There is a lot of illegal, underground publishing. Most is related to sex. A friend told me I’ve got some good news for you: your book on the underclass is competing with the sex books! That was funny. But the two books coming this year are the ones I most value. They are the most personal and have moved me the most. Liao told the New York Times authorities told him “two books of yours can’t be published overseas.” One is the prison book. The other is the God book. They said both are unacceptable. So I talked with them and asked why. They asked me to sign a paper [promising not to publish]. They said these were “illegal cultural products.” They said these two books disclosed secrets.

Liao told writers at a PEN meeting in New York, AFP reported, "I first started wanting to tell stories when I was in prisons. I was locked up with unique people," he said, including traffickers, murderers and thieves. "Gradually my brain was turning into a tape recorder...When I was first locked up I was a political prisoner. I didn’t think I had anything in common," he said, speaking through a translator. ..I felt like my brain was exploding. I couldn’t even take their stories any more. But it was like the only path for them: they wanted to tell their stories to me and they wanted to tell me before they were executed...All the people I have interviewed, they have no interest in politics, but they want the freedom to express themselves." [Source: AFP, South China Morning Post September 14, 2011]

When asked if he recorded the interviews, Liao told the New York Times, “In some of the other books, no. But in this case God is Red I did. But when I write down their answers I try to make it sound as good as possible. I’m a writer so I want to use all my skill to write their stories.” On remembering material for the prison book he said, “I had a copy of [the classic Chinese novel] Romance of the Three Kingdoms and made tiny notes that I put in the book. It was really difficult, but in this way I was able to recover a lot of memories. These books are different. God is Red was difficult because I had to walk a lot of roads and eat a lot of bitterness, but I was glad to be able to write it. They were moving stories. But the prison book was difficult to write. It was painful. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Times August 15, 2011]

On being a oral historian, Liao told ArtSpace China, “I see myself as a tape recorder of contemporary history. My head is like an old-fashioned tape recorder. Some of the old recordings, I erase; some I keep. I’ve written about so many different kinds of people at the bottom of Chinese society: those who’ve been wronged by the court system and are appealing their cases; those affected by the Tiananmen Massacre; people in underground religions; landlords who suffered during land reform. I’ve written about all these different kinds of people. I’ve written out more than 300 stories, so my head has turned into a recording device. [Source: Christen Cornell ArtSpace China, November 29, 2011]

Of course, I think a lot about how to retell the stories I’ve heard. If you’re a tape recorder you have to let these people speak for the whole afternoon, but most of what they say is not important. It’s up to you to isolate their main meaning, to find their essence — the value in their story. This is the job of a writer. If you have three people working on the one story it will be unreadable. I'd say I'm a “documentary writer?.

Liao Yiwu and Corpse Walker

Liao Yiwu is best-known for his book "The Corpse Walker", a colourful collection of interviews with oddballs, crooks, hustlers, toilet-attendants, ex-landlords, so-called rightists, garbage-collectors, and a variety of others whose voices are rarely heard in mainstream Chinese history. First published in Taiwan in 2001, and later in a variety of languages, The Corpse Walker quickly became a bestseller in the West, its success fanned along by the news of the book’s banning in China and Liao’s uncomfortable political position back home. [Source: Christen Cornell ArtSpace China, November 29, 2011]

Among those whose stories are told are “a safecracker who escapes from prison by swimming through a cesspool, hides in a morgue to escape arrest and later takes refuge in an army bus; a peasant who fancies himself emperor; and the “corpse walkers” of the title, who face mob justice for their role in carrying out an obscure rite for the deceased wife of a former Nationalist officer.” [Source: “The Corpse Walker: Real-Life Stories, China From the Bottom Up” by Liao Yiwu reviewed by Howard W. French, The Nation, August 4, 2008]

Howard W. French wrote in The Nation: “If the author's sensitivity for injustice, a consistent focus of his writing, springs from the treatment of his parents that he witnessed as a child, much of his technique, including a finely honed sense of voice and dialogue, was forged in prison, where he shared cells with hardened criminals, eccentrics and outcasts from China's socialist order. In The Corpse Walker Liao's interviews are presented in standard question-and-answer format, a method that would seem to leave little room for style, but the effect of reading them is almost akin to that of reading the work of a skilled short-story writer, one with a talent for getting out of the way and letting the yarn unravel, as if all on its own. Part of this stems, undoubtedly, from what might be called remarkable people skills--the ability to sidle up to someone and get a sympathetic current flowing, without the subject ever the wiser that he is being pumped.”

“Read four or five of these interviews, though--there is little chance of stopping there--and something powerful begins to happen. Doubts about the plausibility of this or that detail begin to morph into doubts of an altogether different kind, ones that seem close to the heart of the author's project. And these big new doubts go to the very nature of the China that we think we have known.”

Book: “The Corpse Walker: Real-Life Stories, China From the Bottom Up” by Liao Yiwu

Prison Justice in China According to a Yiao Yiwu Interviewee

Tian Zhiguang, a man who was been arrested for supposedly robbing graves, told Liao Yiwu in the book “The Corpse Walker: Real-Life Stories, China From the Bottom Up” : “From the unexpected discovery of fortune to our sudden arrest, everything happened so fast,” Tian said, explaining how the discovery of antique gold coins buried beneath his house led to his arrest on a false pretense. Police dismissed his explanation with a laugh and carted him off to jail, where the inmates initially took Tian for the leader of a grave-robbing “triad,” or gang, and treated him with respect. Weeks later, when they learned he was an ordinary inmate, he was given a belated initiation, which consisted of vicious beatings while being forced to hoist a fully laden prison cell chamber pot on his head.” [Source: “The Corpse Walker: Real-Life Stories, China From the Bottom Up” by Liao Yiwu, reviewed by Howard W. French, The Nation, August 4, 2008]

“Two weeks after his initiation, Tian is offered a chance at redemption through the detention center's “Confession Leads to Leniency” campaign. Three hundred inmates from nine cells are called into the courtyard to appear before local police and Communist Party leaders, who repeat over and over that “confessions will lead to reduced sentences.” Later, the bullying overlord among the inmates urges him to recant. “Those officials out there are all liars. Under normal circumstances, they trick you into confessing, promising you the reward of a reduced sentence. Once you tell everything, they never keep their promise. You probably end up with a bullet in your head. However, this campaign is different. The media has written about it. If those officials renege on their promises, they will lose face and credibility.”

“Throughout his ordeal, Tian has remained scrupulous, and he responds by saying what he has told the authorities from the start: “I don't really have anything to confess.” The boss of the cellblock, sensing a chance to win points, orders his underlings to rough up Tian in order to change his mind. “The cell was like a classroom and every 'student' was asked to write a paper,” Tian relates. “Your confession needs to be sensational,” the boss tells them. “Don't try to simplify and whitewash. The more serious your crimes are, the better it makes me look.”

Liao Yiwu’s Prison Book

Liao’s prison memoir, “For a Song and a Hundred Songs: A Poet’s Journey Through a Chinese Prison” was published in 2013 but was banned in China. It was a best seller and prizewinner in Germany; won critical acclaim in France and has been translated into Czech, Italian, Polish, Portuguese, Spanish and Swedish. The English-language version was published by New Harvest. [Source: Elaine Sciolino, New York Times, April 9, 2013]

Elaine Sciolino wrote in the New York Times: Liao “began his memoir in 1990 on the backs of envelopes and scraps of paper his family smuggled into prison. He managed to sneak out his manuscript when he was released. But twice it was confiscated, and he had to reconstruct it from memory both times. The title refers to an incident in prison when he broke the rules by singing; as punishment, he was ordered to sing 100 songs. When his voice gave out, he was tortured with electric shocks from a baton inserted into his anus. “I felt like a duck whose feathers were being stripped,” he writes.

“In the book he describes the rigid hierarchy the prisoners created for themselves. At the top was a chief with enforcers, a housekeeper and cabinet members; at the bottom were several groups of “slaves,” including “hot water thieves” who brought the upper classes hot water and gave massages; “laundry thieves,” who washed clothes and crushed fleas in the bedding; and young, handsome “entertainment thieves” who sang, danced and performed skits and sex acts with the leaders. As a political prisoner, Mr. Liao was fortunate to be placed in the “middle class,” a status that came with certain privileges — he could bring his meals back to the cell and eat at his own pace, for example — and that spared him some of the abuse suffered by the underclasses.

“Early on the chief gave him a long menu of “dishes” of torture, to choose what to be served if he disobeyed an order. Among them were “Sichuan-style smoked duck” (the enforcer burns the inmate’s pubic hair and penis tip); “noodles in a clear broth” (the inmate eats a soup of toilet paper and urine); and “naked sculpture” (the inmate stands naked and strikes different poses ordered by the chief).

“Mr. Liao’s most terrible prison memory was not of torture, deprivation or even watching fellow inmates sent for execution. It was of a failed suicide attempt. Handcuffed, bound with ropes and subjected to electric shocks, he decided to kill himself. He hurled his body forward, hitting his head into a wall. “All the prisoners accused me of faking it, of being a good actor,” he said during the interview. “Nobody believed I wanted to die. I was angry — terribly, terribly angry. Nobody cared.”

“Along the way Mr. Liao learned survival skills. A fellow prisoner taught him to stand on his head as a form of exercise and relaxation. Another, a Buddhist monk in his 80s, taught him to play the xiao, an ancient, flutelike instrument. Another made writing pens from bits of bamboo and wood. Another, a Bible-reading inmate, looked out for him and gave him wisdom.Even now, he experiences a recurring nightmare. “I am flying and I see people on the ground with guns and knives running after me,” he said. “But I am a bird without legs, and when I can’t fly anymore, I fall to the ground. The people come nearer and nearer, and as soon as they are about to attack, I wake up filled with terror.”

Philip Gourevitch of The New Yorker wrote, The German edition of Liao’s prison memoir—“The Witness of the 4th of June” — runs to five hundred pages, and was supposed to appear in April. But after the Chinese police threatened him, it was postponed until June, and then postponed again, and the Taiwanese edition (the first Chinese edition), was also postponed. In this way, the publication of the book recalled Liao’s ordeal in writing it, for he wrote it three times: the first manuscript was confiscated in the nineteen-nineties during a police search of his home, so he rewrote it, and that manuscript was taken from him by the police in 2001. When he finished the manuscript for the third time last year, he got it out of the country to safety, and today when he followed it, his German publisher, Peter Sillem of Fischer Verlag, told me that it will be published in August. [Source:Philip Gourevitch, The New Yorker, July 6, 2011]

Liao Yiwu on Prison Torture and Suicide

Liao told the New York Times, “The prison book is pretty cruel. I was serving time in Chongqing. At one point they tortured me so much I smashed my head against the wall to try to kill myself. I passed out and then over the next few days the non-political prisoners came by and said, “Hey buddy, if you really want to kill yourself that’s a stupid way to do it. A better way is like this: you find a nail sticking out of the wall and smash your temple against it. It’s much more effective, believe us.” So this book is maybe more cruel than the others. The authorities said to me: “If you publish this book we’ll send you back to Chongqing.” There’s no way I’m going back there. That’s too terrifying. They said we don’t care about the Mao era. You can write about that. The 50s and 60s are okay. Liao told the PEN gathering in New York he was known to other prisoners as "the big lunatic" for his defiant gestures. When a thief on death row asked him to organise for him "the same memorial service as accorded to a senior Chinese leader, Liao obliged, writing a eulogy that got him sent into solitary confinement as a punishment for 23 days. "That’s why they called me the lunatic." [Source: AFP, South China Morning Post September 14, 2011; [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Times August 15, 2011]

Ian Buruma wrote in The New Yorker:“At the Chongqing Municipal Public Security Bureau Investigation Center, for example, also known as the Song Mountain Investigation Center, the cell bosses devised an exotic menu of torments. A few samples: 1) Sichuan-style Smoked Duck: The enforcer burns the inmate’s pubic hair, pulls back his foreskin and blackens the head of the penis with fire. Or: 2) Noodles in a Clear Broth: Strings of toilet papers are soaked in a bowl of urine, and the inmate is forced to eat the toilet paper and drink the urine. Or: 3) Turtle Shell and Pork Skin Soup: The enforcer smacks the inmate’s knee caps until they are bruised and swollen like turtle shells. Walking is impossible. [Source: Ian Buruma, The New Yorker, July 1, 2013]

“There are other tortures, too, meted out in a more improvised manner. Liao Yiwu, in his extraordinary prison memoir, “For a Song and a Hundred Songs” (translated from the Chinese by Wenguang Huang; New Harvest), describes the case of a schizophrenic woodcutter who had axed his own wife, because she was so emaciated that he took her for a bundle of wood. The cell boss spikes the woodcutter’s broth with a laxative, and then refuses to let him use the communal toilet bucket, with the result that the desperate man shits all over a fellow-inmate. As a punishment for this disgusting transgression, his face is smashed into a basin. The guards, assuming that he has tried to commit suicide, a prison offense, then work him over with a stun baton.”

Liao “is ruthlessly candid about his weaknesses, and his fears. There is nothing especially heroic about him. Watching the guards in combat training on his first day in prison, he “shuddered like a nervous rat.” Forced to sing songs over and over again with a parched throat in the freezing cold to entertain the guards, he is beaten with an electric baton. When he cannot go on any longer, he is stripped and wrestled to the ground: “I could feel the baton on my butthole, but I refused to surrender. The tip of the baton entered me. I screamed and then whimpered in pain like a dog.” Liao tried to commit suicide twice, once by bashing his head against the wall. This elicited ridicule from his cellmates, who accused him of playacting, something they thought typical of a bookish poet. If he had really wanted to smash his skull, he should have made sure to use the wall edge.

Liao Yiwu on Writing in Prison and Having His Work Confiscated

On how he dealt with having his manuscripts confiscated, Liao Yiwu told New Yorker writer Jiayang Fan: When the book was first confiscated, I experienced a kind of total devastation. At that time I was also put under unofficial house arrest for more than 20 days. I was scared. I didn’t know what they would do. But, fortunately, I’d written the draft in very tiny script, like an ant would. They probably needed a microscope to read it clearly. The second time, when it was confiscated again, I was a little more numb to the experience. And by the third time, I had a computer. With a computer, you can have a lot of back-ups. So my writing process took me from the age of da Vinci to the computer age. [Source:Jiayang Fan, Asian American Writers Workshop, January 28, 2014]

“Each time that I was forced to start from the beginning, I thought, “Last time I wrote it better than this time!” But you know, that’s not necessarily the case. I always thought, “How is it that the more I write, the shorter it gets?” The first time, I wrote more than 300,000 characters. The second time, it was only 200,000. The third time, it dropped another 20,000 characters. I thought, “I’ve definitely forgotten a bunch of the details.” But there were also some surprises. For example, I’d think, “Oh I don’t think I included this example last time.” But it’s true with this as it is with women: always more beautiful in your memory.

On writing in prison, Liao said: “From the moment I was detained I only had one chance a month to write a letter. So I couldn’t write much, just some short poetry. Then I was sentenced and transferred to the re-education through labor prison. In the re-education through labor prison, I wrote some novels. After I got out, it was very strange because I’d been able to take out the drafts I’d written in prison. I’d hidden them early. But this draft, because I was writing it all the time, was discovered a lot. It was pretty much a joke.

Liao Yiwu’s Christian Book

Liao’s recent book, God is Red, is another collection of interviews, this time with elderly Chinese Christians whose faith has brought them into conflict with the state. “God is Red: The Secret Story of How Christianity Survived and Flourished in Communist China” tells the story of Christian persecution in the early Communist era, mostly in minority areas of Yunnan province. He has also written that has just been published in Germany to wide acclaim. His fourth book, on China’s new underclass, has yet to be published. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Times August 15, 2011]

On why he wrote about Christians, Liao told the New York Times, “I’m the kind of person who doesn’t have a definite plan. I had this opportunity to meet the Christians and it moved me so I did it. I was in Yunnan trying to interview the last landlords of China, the ones who were persecuted in the early communist years. I met some people who told me about these Christians. I went to meet them. It was a really poor place. Unbelievably poor. No electricity, no roads, no telephone. We walked four or five hours to get to one village. But I thought this was so unbelievable. You’d get to a village and there’d be a church.

Westerners had been there before, a century earlier, and built these churches. It was remarkable. They worked in these villages until 1949 when the Communists took over. The foreigners were expelled and a lot of the Christians killed. The stories are unbelievably cruel. In one case the father was executed and left on the side of the road. The family wasn’t allowed to pick up the corpse. When I heard this I cried.

Liao said that while he is not a Christian, he admires their determination and faith. Like other forms of self expression, all religions are permitted on one condition: "First you have to believe in the Communist Party". "If you are willing to pursue your freedom, seek out your freedom, then you could be in trouble," he said. [Source: AFP, South China Morning Post September 14, 2011]

Liao Yiwu on Christians in China

When asked where his interest in Christianity came from, Liao said, “It began when I met a doctor who was working in the remote areas of Yunnan, moving from village to village. This man had originally been the vice-director of a hospital in the city. Later, he’d gone for a promotion and had been told that if he wanted to become the actual hospital director he’d have to become a member of the Chinese Communist Party. Until that point the hospital hadn’t known the doctor was a Christian, but when they asked him to join the Party he refused. He said: I already have my faith. I have faith in God, so I can’t have a second faith in the Party. After this he left the hospital and moved to the countryside to treat people there. This man was an amazing person. The first time I met him was in a very basic room where he was giving an old lady cataract surgery. These two people were holding two torches, and that’s how they were working. Almost in darkness, using torches to conduct cataract surgery! [Source: Christen Cornell ArtSpace China, November 29, 2011]

Later, he told me that he knew a lot of Christians who had been wronged, and asked if I wanted to go with him to meet some of these people and hear their stories. Of course I was interested, so I went with him. I interviewed many elderly Christians, heard many stories, and their stories were extremely moving. The people in these stories weren’t like those in conventional Christian church groups. Some of these Christians had been killed for their beliefs, some had been imprisoned for years.

There was this one man called Wang Zeming, he was considered to be the most compassionate, to have the greatest faith of all Christians of the last century. He’d been officially recognised in a church in some English city. His story was during the Cultural Revolution; he’d been told to dance the patriotic “Mao Dance” but he’d refused. He said, publicly, there is no way that I can dance the Mao Dance, and there is no way I can declare my loyalty to Mao, because I already have faith in God. He said that publicly.

Of course he was immediately arrested, and for four years they tried to change his views. They tried to brainwash him, but they couldn’t do it. In the end they asked him: Are you going to change your views? Will you declare your faith in Mao? And again, he said: I believe in God, so I can’t believe in Mao. They took him to a denunciation meeting where there were more than a million people. And shot him dead.

I think that faith is an incredibly powerful thing, regardless of what religion you find it in. I'm not Christian but I'm interested in belief, especially the kind you find in very common people, in poor people. I think this is an extraordinary thing. At first I was thinking that if faith was this powerful it could inspire and motivate so many people, but later I became extremely disappointed in other Christians, in Christian groups in the cities and elsewhere. They were already a long way from the original essence of their religion. I discussed this in America too, the corruption of church institutions. They’ve turned God into something for their own purposes.

The churches of the countryside and the cities are totally different. Those in the countryside are very poor, and the people in them too. For them, religion is an essential part of their daily lives, it brings them together and inspires compassion. I think that religion is purest in the most remote places. These people only have God, nothing else. That is a real faith. The Christians in the city are different.

Image Sources: Amazon, Wiki Commons, Human Rights in China, Laogai Museum

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021