YU HUA ON CENSORSHIP IN CHINA

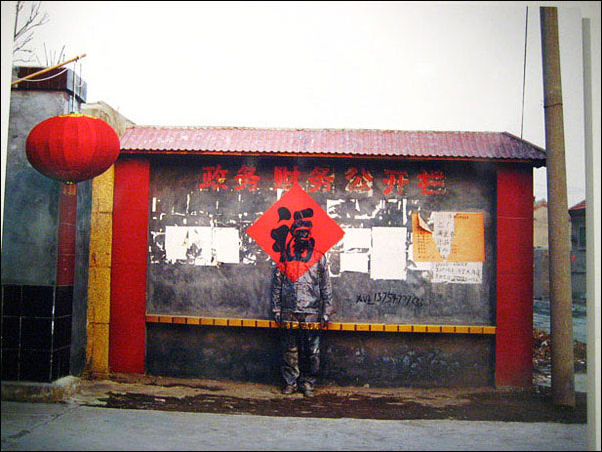

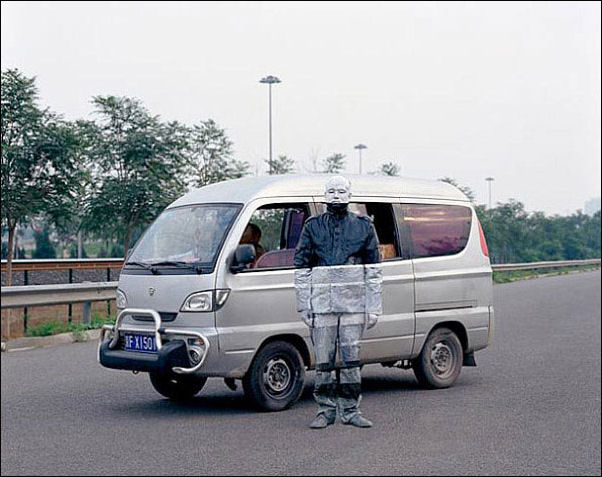

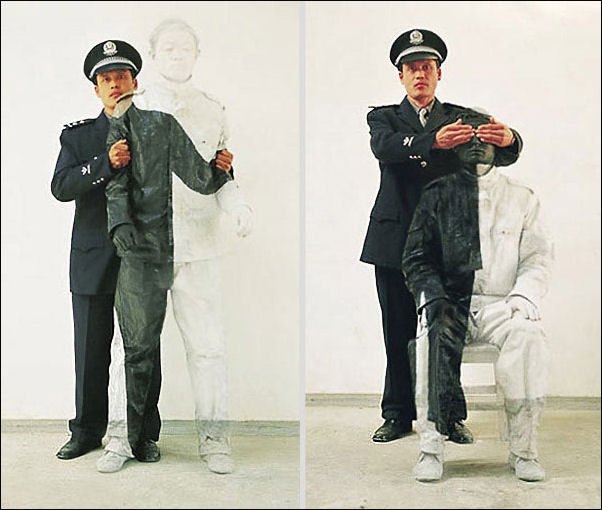

Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist The famed and popular Chinese writer Yu Hua wrote in the New York Times: Censorship in China conjures the image of rigid, unsmiling authority, but that disapproving scowl can give way to a different expression — and not always a consistent one. A film, for example, might be banned for 20 years, while the novel on which it is based sells briskly throughout that same period. This might seem puzzling, but the reason is simple. China has more than 500 publishing houses, each with its own editor in chief (and de facto censor); if a book is rejected by one publisher there’s still a chance another will take it. In contrast, films are not released until officials in the state cinema bureau in Beijing are satisfied, and once a film is banned it has no hope of being screened. [Source: Yu Hua, New York Times, February 28, 2013]

“When it comes to censorship in China, the primary factors are often economic, not political. Publishing houses that were once government financed have operated as commercial enterprises for years now. Editors are under pressure to make the biggest profit they can. Even if a book carries some political risks, a daring editor will take the gamble if there’s a chance it will be a best seller.

“To be sure, there are some limits in book publishing — the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 are taboo, for example — but fewer than in film. That’s because film censors, unlike book publishers, don’t have to worry about making profits. Each script is scrutinized, and only after it’s approved can filming commence. Review of the finished product is even more exacting. Even if they were to reject every project that comes their way, it wouldn’t affect their salaries, so they are not prepared to take on the least political risk. That’s why the Cultural Revolution and other sensitive topics are regularly discussed in print but remain off-limits on film. If you go to a cinema, all you’ll see, basically, are martial-arts films, palace dramas, love stories and comedies — and a few American movies.

“Television censorship is a bit less strict. Programming directors decide what gets broadcast, but the propaganda ministry often demands changes. China Central Television, the state broadcaster, is the most carefully monitored; regional stations have more leeway. News programming undergoes the strictest censorship, while other programs — particularly sports — have more freedom.

“Newspaper censorship is also relatively more relaxed than film censorship, but stricter than book censorship. Stricter because the Communist Party puts more stress on control of the press (“journalism is the Party’s mouthpiece,” the saying goes). More relaxed because the press has to make its way in the marketplace. Newspapers need circulation and advertising revenue, so they publish lots of stories about social problems and injustices, because that’s what readers want. When newspapers got government subsidies, they were politically and economically beholden. Now their subservience can’t be counted on. As the economic base crumbles, the superstructure threatens to collapse.

“The newspaper Southern Weekend, based in Guangdong Province, for years published exposés on corruption and malfeasance, becoming one of China’s most popular news outlets. Shrewdly, it focused its muckraking on other provinces, with the result that local censors often cut it slack. Papers elsewhere began to take their lead from Southern Weekend, dispatching investigative reporters far afield while carrying upbeat news about the situation close to home.

“The highly publicized demonstrations in January over censorship of Southern Weekend were a rarity: a “mass incident” (as China calls such protests) over the media. A propaganda chief who’d parachuted in from Beijing had meddled so crudely with a routine editorial that he triggered a revolt among editors and reporters. Other newspapers lent support to the protesters, while on the Internet the outrage was even stronger. Soon it was all hushed up. The paper has continued to publish. The authorities offered vague commitments of gentler censorship, but have quietly begun retaliating against those who took a stand. The government won in the end, but its censorship had encountered — for the first time in decades — head-on resistance from a press that has become far less docile.

“On Weibo, a kind of Chinese Twitter, I recently made a joking comparison between media censorship and the pervasive threat of contaminated food, a constant source of worry: “There’s no end to these food scares,” a friend sighed. “Is there any hope of a solution?” “Oh, all we need is for food inspections to be as forceful as film censorship,” I told him breezily. “With all that faultfinding and nit-picking, food-safety issues will be resolved in no time.” More than 12,000 readers reposted this. One wrote: I know what we should do. Let’s have those in charge of film, newspaper and book censorship take over food safety, and have those responsible for food safety censor films, papers and books. That way we’ll have food safety — and freedom of expression as well!

See Separate Articles: CULTURE AND LITERATURE factsanddetails.com; CHINESE CULTURE AND PERFORMING ARTS factsanddetails.com ; INTELLECTUALS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CULTURE UNDER THE COMMUNISTS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CULTURAL REFORM IN CHINA AND CRACKDOWNS UNDER XI XINPING factsanddetails.com ; ART AND CRAFTS factsanddetails.com; MUSIC, OPERA, THEATER AND DANCE factsanddetails.com; FILM AND ACTORS factsanddetails.com; TELEVISION AND MEDIA factsanddetails.com; INTERNET AND COMMUNICATIONS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Chinese Culture: China Culture.org chinaculture.org ; China Culture Online chinesecultureonline.com ;Chinatown Connection chinatownconnection.com ; Transnational China Culture Project ruf.rice.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Trickle-Down Censorship: An Outsider's Account of Working Inside China's Censorship Regime” by JFK Miller Amazon.com; “Censored: Distraction and Diversion Inside China's Great Firewall” by Margaret E. Roberts Amazon.com; “The Contentious Public Sphere: Law, Media, and Authoritarian Rule in China” by Ya-Wen Lei Amazon.com; “We Have Been Harmonized: Life in China's Surveillance State” by Kai Strittmatter, Matthew Waterson, et al. Amazon.com; “Made in Censorship: The Tiananmen Movement in Chinese Literature and Film” by Thomas Chen Amazon.com

History of Censorship in China

Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist

preparing for a piece Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times, “Chinese rulers have long had a complicated relationship with books, promoting ones that enshrine official thought and history while banning or destroying others. Qin Shihuang, ancient China’s unifier, burned books and buried scholars alive. In the 18th century, the Qianlong Emperor purged thousands of texts and their authors for treasonous ideas while assembling a vast imperial collection to be printed. Mao Zedong and his comrades were no different. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, November 6, 2011]

On the 19th century Chinese government Censorate, Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”: “Here is a considerable body of men, who are supposed to be acting in the interests of their own ideals, and who, whenever they see any irregularity in any official, nay in the Son of Heaven himself, are supposed to make it known to the. Emperor, who (like all other officers) is thus in the presence of a chronic Day-of-Judgment, to which he is himself amenable, albeit he is himself the sole judge of every case. The antecedent probabilities of the Chinese social structure would seem to be against the invention of any such tribunal as the Censorate, as well as against its efficient action, when it is constructed. Yet there can be no doubt from the little that is allowed to filter through the opaque medium of the Peking Gazette, that these officers do really brave a great amount of obloquy in some cases, and sometimes appear to delight in giving as much offence to all concerned as possible. But this after all may be nothing but a kind of give-and-take arrangement, subject to the laws which are seen to govern the most ordinary Chinese transactions. [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894. Smith (1845 -1932) was an American missionary who spent 54 years in China. In the 1920s, “Chinese Characteristics” was still the most widely read book on China among foreign residents there. He spent much of his time in Pangzhuang, a village in Shandong.]

Evan Osnos wrote in the New York Times:“For most of Chinese history, readers had limited access to books from abroad. In the 1960s and ’70s, when foreign literature was officially restricted to party elites, students circulated handwritten, string-bound copies of J.D. Salinger, Arthur Conan Doyle and many others. But in the past three decades, rules have relaxed somewhat and sales of foreign writers have ballooned, thanks to Chinese consumers who are ravenous for new information about themselves and the world. [Source: Evan Osnos, New York Times, May 2, 2014]

Wong wrote: As intellectual discourse began to flower again in the 1980s, writers like Yu Hua, Mo Yan, and Su Tong cast a critical eye on Chinese history and rural society. Wang Shuo wrote urban “hooligan” literature. But it was the spread of the Internet in the late 1990s that really opened the floodgates. Younger writers went online to tell tales of boom-era China. One Web site, Rongshuxia, was particularly influential, carrying novels by Annie Baobei, Ning Caishen and Li Xunhuan (the pen name of Lu Jinbo, now a prominent publisher who supports Mr. Murong). In recent years, the Internet has popularized genre fiction, and bookstores here now stock the whole gamut: science fiction and fantasy, horror, detective, teenage romance and, most lucrative of all, children’s stories.

Censorship in Chinese Literature

Dissident writers that are well-known outside of China and have large numbers of readers abroad are largely; unknown in China. If they are known they have little sympathy. In February 2007, China prevented 20 China writers from attending an international conference in Hong Kong.

China has a vast censorship apparatus.The Chinese Press and Publications Administration is the official watch dog and censor of the publishing industry. Even though many kinds of books have to be approved by the agency, these days so many books are being published it can't keep track of them all. Still in late 2006 it banned eight books — including a novel about a man who lived through the Communist Revolution and the Great Leap Forward and a book about Peking Opera stars — and threatened publishing houses with severe penalties if they published works the government didn’t like.

Writers often write keeping in mind how the censors will react, Some write two parallel versions of their work: one for the censors and one themselves or the foreign market. A writer whose book was banned told the New York Times, “Nothing is communicated formally to the writer. Nothing is committed to paper. It’s all done in a secretive way, through oral communications. In my case I found out about my book’s banning on the Internet.” When asked how he knew for sure his book had been banned, the writer said, “Many thing in China can’t be verified, but they are carried out very clearly in reality.”

“Writers have to ensure that they do not broach sensitive topics, or only tackle them obliquely. The internet and rampant piracy means many banned books do not stay unread for long. Yet the threat of a book being shut out of the main domestic market means authors have to step carefully if they want to make a living from their art, even if the censorship system today is not the terrifying beast it was during the hardline Maoist era.” [Source: Ben Blanchard, South China Morning Post, Reuters, May 4, 2009]

“Wang Gang, the quick-witted, urbane author of the Chinese best-seller English, a semi-autobiographical novel about growing up in Xinjiang during the Cultural Revolution, admits he had to self-censor his book to get it passed by the authorities.” Generally speaking, there is freedom, but there are things I did not write about,” Wang says at the launch of the English-language translation of his book. “For example, I did not mention the missionary background of the English teacher [in the novel] nor ethnic problems in Xinjiang. I feel regret about that." On how he was able to write so candidly about a period all but removed from government-vetted history texts, Wang said "Officials don't read any more,” he says. “That's how this book had a chance to come out.”

Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist

and his take on censorship

Film and Television Censorship in China

Films and television programs are particularly tightly controlled. One film director told the Guardian that censors demanded 400 changes before they would pass his movie. State Administration of Radio, Film and Television, also known as SARFT, is the main regulator and censor of films. In 2010, a total of 526 films it had approved were made.

Television shows and films are approved and censored by the various government agencies. Taboo subjects include explicit sex, nudity, graphic violence, gambling, adultery, ghosts and criticism of the Communist party. Sometimes films are cut for the oddest reason. On action movie, for example, had a scene removed in which a policeman is zapped to death by an electric eel in a swimming pool because it depicted a "unrespectable" way to die. Films that please the censors often turn out to be yawners that no one is interested in seeing.

There has traditionally been no rating system. A film made in China has be acceptable to people of all ages, including children. In recent years there has been some discussion about starting a rating system. Theoretically under such a system more sex and violence would shown is films given an dual rating but it is unclear how much.

See Separate Article FILM, CENSORSHIP, CRITICISM AND THE CHINESE GOVERNMENT factsanddetails.com

Censorship Process in China

On why his reformist magazine? Annals of the Yellow Emperor” seems to enjoy more leeway than other Chinese publications, Yang Jisheng told the New York Review of Books, Because we know the boundaries. We don’t touch current leaders. And issues that are extremely sensitive, like 6-4 [the June 4th Tiananmen Square massacre], we don’t talk about. The Tibet issue, Xinjiang, we don’t write about them. Current issues related to Hu Jintao, Jiang Zemin and their family members” corruption, we don’t talk about. If we talk just about the past, the pressure is smaller.

Describing how the censorship process works, Internet writer Murong Xuecun said in a speech at the Foreign Correspondents Club in Hong Kong: “My new book tells the story of my time spent undercover inside an illegal pyramid-sales organization. It included this phrase: “This group, mostly made up of people from Henan, was called the “Henan network.”“ To the editor, this harmless sentence aroused safety issues because the phrase “Henan people” carries an air of regional discrimination. He suggested that we rework the phrase as: “They were all Henan peasants, and so this network was called the Henan network, and was made up of mostly Henan people.” I asked him why. He said that by changing “people” to “peasants,” more sophisticated Henan people would not feel slighted.[Source: Murong Xuecun, International Herald Tribune, February 23, 2011]

“I tried to bargain with him: “In my original version there were two sentences, it would be too wordy if there were three. Why don’t we cut the first one?” He thought about it for ages and then agreed, and so we arrived at the final version: “This group, called the “Henan network,” was made up mostly of Henan people.” In the end, all that changed was the word order. As you may have guessed, this editor didn’t just cut a few words like “Henan people,” but also many sentences, paragraphs and even whole sections and chapters.”

“From my many years” experience in writing and publishing, I could compile a Sensitive Words Glossary, in which you would certainly find the words ‘system,” “law,” “government,” as well as a large number of other nouns, several verbs, quite a few adjectives, and even a few special numbers. The glossary would also include all names of religions, all names of important people, all countries, including of course China, and also the phrase “Chinese people.”“

“In many places in my new book, “Chinese people” was changed to ‘some people,” or even “a small number of people.” If I critiqued some part of traditional Chinese culture, the editor would change it to “the bureaucratic culture of ancient China.” If I brought up anything contemporary, he would ask me instead to refer to Zhu Yuanzhang, the founder of the Ming Dynasty, or Wu Zetian, a notorious Tang dynasty empress, or Europe of the Middle Ages. Readers of my book may think I’m mad. Obviously I’m writing about contemporary things so why am I repeatedly criticizing Empress Wu” Well, the reader may be right: At this time, in this place, Chinese writing exhibits symptoms of a mental disorder. I am not a Chinese writer so much as a person with a mental disorder.”

“Unfortunately, I have dedicated great effort to the task of compiling this Sensitive Words Glossary, and I have mastered my filtering skills. When I wrote my latest book, I knew which words had to be cut, and I accepted the cutting as if that was the way it should be. In fact, I will often take it on myself to save time and cut a few words. This is castrated writing. I am a proactive eunuch, I castrate myself even before the surgeon raises his scalpel. Our language has been cut into two parts: one safe, and the other risky. Some words are revolutionary, and others are reactionary; some words we may use, and others belong to our enemies.”

“The most unfortunate thing is that despite my experience, I still don’t always know which words are legal and which illegal, and as a result I often unknowingly commit a “word crime.” When I stand at a podium to receive a prize, I feel uncomfortable calling myself a writer — I am merely a word criminal.... This is our great language, the language of the philosopher Zhuangzi and the poets Li Bai and Su Dongpo and the grand historian Sima Qian. Maybe our grandchildren and the children of our grandchildren will rediscover many beautiful words and phrases that no longer exist. But sadly, even now, we continue to arrogantly proclaim that our language is on the rise.”

Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist

Government Control of Publishing in China

Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times, “More books are being printed now than at any time since the Communist Party took power in 1949. In 2010, about 328,000 titles were published, more than double the number in 2001, according to official statistics.But the government still wields important instruments of control. The agency overseeing the industry, the General Administration of Press and Publication, has not allowed real growth in the houses officially allowed to publish books. Last year, there were 581 such houses, just 19 more than in 2001. All are state-owned, and the government is moving to consolidate them. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, November 6, 2011]

Those numbers do not capture an important phenomenon: Market demand has led to a boom in private houses. To publish, they must either form joint ventures with the state-owned houses or, more often, buy from them International Standard Book Numbers codes, one for each title. On paper, this practice is illegal, but the authorities turned a blind eye to it for years. A tightening could be in the works — this year, officials have said they prefer that the private houses enter into joint ventures, which would mean more oversight and would help push state-owned enterprises toward the market.

As for censorship, chief editors act as the ultimate gatekeepers. They know they could lose their jobs if published material raises the ire of officials. Nonfiction books on special topics like the military or religion go through additional vetting by the relevant ministries. In the industry, “there is a shadow over the hearts of everyone,” said Mr. Lu, the publisher. In June 2011, officials made an example of Zhuhai Publishing House, a small state-owned company, by abruptly shutting it down. Zhuhai had published a memoir by Jimmy Lai, a Hong Kong newspaper publisher reviled by some Chinese leaders.

Self Censorship and Writing in China

Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times, “Writers looking to avoid these difficulties end up doing the government’s job for it. Mr. Murong said he had abandoned two novels-in-progress that he suspected would never get published. One was called “The Counterrevolutionary.” [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, November 6, 2011]

“The worst effect of the censorship is the psychological impact on writers,” Mr. Murong said. “When I was working on my first book, I didn’t care whether it would be published, so I wrote whatever I wanted. Now, after I have published a few books, I can clearly feel the impact of censorship when I write. For example, I’ll think of a sentence, and then realize that it will for sure get deleted. Then I won’t even write it down. This self-censoring is the worst.”

Mr. Murong argued with Mr. Lu when they were completing plans in 2008 to publish “Dancing Through Red Dust,” about the corrupt legal system. Mr. Lu, who had bought an ISBN code from Zhuhai Publishing House, told Mr. Murong that he wanted to limit the print run because the book was too sordid. In an interview, Mr. Lu said Mr. Murong was “the best writer under the age of 40,” but added that “Murong has one problem: his writings are too dark.” “He’s a loner nihilist who believes in nothing,” Mr. Lu said.

Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist

On Self-Censorship By Ai Weiwei

In an e-mail to Huffington Post, during his own struggles with authorities and censors, the famed Chinese modern artist Ai Weiwei wrote, “Censorship in China is enforced 24 hours a day, and operates in every channel of communication. Its impact resounds in all forms of individual expression related to the public, be it a publication, an art show, or a website. For over 60 years, policies of censorship have been a pervasive part of society throughout the nation. [Source: Mallika Rao,Huffington Post, June 19, 2014]

“Within a month, my name has been omitted from two exhibitions in China. Most recently, the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art (UCCA) in Beijing was showing three of my pieces in an exhibition commemorating an old friend and colleague, but were afraid to mention my name and my relationship with the institution that my friend and I built together — the first Chinese contemporary art institution ever created.

“When these incidents are observed as part of a bigger picture, the severity of the issue can be clearly understood. This strict censorship of information and expression affects not only myself, but the artist community and the whole of society. For mixed reasons, institutions are self-censoring in order to survive, some even to reap benefits.

“In a conversation with Philip Tinari, director of the UCCA, he mentioned “threats” from above that led to the omission of my name in the exhibition. In China, party policies may not affect you as an individual, but work through your organization, your landlord, your relatives and your associates. Even if you act independently, the power influences those around you.

“Intimidation is the most efficient tool for those in power to scare away people’s sense of independence. Not only can they successfully expunge ideas from the public sphere and purge those who dare to express these ideas and attitudes, they can also brainwash anyone who simply wants to function as a part of society. In order to gain financial and personal security, people need to conform to behavioral standards without asking any questions or attempting to tell right from wrong. Censorship is a system that creates absolute power and paralyses society, removing the people’s courage to make judgments or bear social responsibility.

“Censorship and self-censorship act together in this society to ensure that independent thinking and creativity cannot exist without bowing to authority. More often than not, self-censoring and the so-called threats related to it, are based on a memory or a vague sense of danger, and not necessarily a direct instruction from high officials. The Chinese saying sha ji jing hou puts it succinctly: killing the chicken to scare the monkey. Punishing an individual as an example to others again incites this policy of intimidation that can resound for lifetimes and even generations.

“Unlike most parts of the world, China’s internet is based on local area networks (LAN), but even this limited information flow is already making the authorities extremely nervous. Not only does online censorship go against the essential character of the Internet, it has already led to many arrests and sentences in persecution of freedom of expression. As a result, self-censorship is on the rise, while the demand for freedom grows at an equally rapid pace. These are parallel challenges facing us in the materialistic world in which we live.

Imprecise Boundaries and Unpredictability of Chinese Censorship

Evan Osnos, the author of a couple of books about China, wrote in the New York Times: “Living and writing in Beijing from 2005 to 2013, I found that the precise boundaries of the censored world were difficult to map. Though some rules leak to the public — last month, the State Council Information Office advised all websites to “find and remove the video titled ‘Actual Footage of Chengdu Police Surrounding and Beating Homeowners Who Were Defending Their Rights”’ — most of the censored world is populated by unmentionable names and untellable stories, defined by rules that are themselves secret. [Source: Evan Osnos, New York Times, May 2, 2014]

“The Central Propaganda Department, the highest-ranking agency responsible for “thought work,” does not report on its activities; it is so averse to attention that its headquarters, on the Avenue of Eternal Peace, have no address or sign. To quantify one realm of Chinese censorship, researchers at Carnegie Mellon University, in 2012, studied messages on Sina Weibo, the social media site. They found that more than 16 percent of all posts were deleted because of the content.

“Some taboos were foreseeable; the publisher worried about a mention of Mao’s Great Leap Forward, because that project resulted in a famine that killed between 30 and 45 million people. Other problems were subtler; since the party credits its economic success to Deng Xiaoping, I was advised not to lavish too much praise on the contributions of his peers. Judging by the notes, the censor seemed to grow exasperated: “Chapter 14: The whole chapter is about Chen Guangcheng.” (I write about Mr. Chen, a blind lawyer now in exile in the United States, as an example of Chinese determination to defy the circumstances of birth.)

“In some cases, the censors’ requirements startled me: The former politician Bo Xilai, a one-time rising star now serving a life sentence for corruption, was convicted in a trial covered by state television, so why is discussion of him sensitive? The problem, it seemed, is how it can be mentioned, and how much. When an official version of history has been written, an unofficial version becomes unwelcome.

Chinese Writers Persecuted by the Communist Government

Except for Liu Xiabao, the jailed Nobel laureate, most Chinese writers who cross the authorities suffer in relative anonymity. Their works are banned, employment opportunities dry up and their daily movements are constrained by security officials who prevent them from leading normal lives. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times July 23, 2011]

Jiao Guobiao, a Beijing journalism professor who lost his job after writing a critique of the Communist Party, offered a precise tally of the restrictions on his movements. In 2010, he said, he was confined to his home for 249 days. On other days, he was required to receive permission to meet with friends. “On the days I could go out, I had the feeling I was being followed,” he said.

In 2010, Cui Weiping, a poet and film scholar, Cui was prevented from going abroad to attend a film conference in the United States; the nonfiction writer Liao Yiwu was pulled off a plane that was to take him to a literary festival in Germany. After 17 failed attempts to leave China, Mr. Liao surprised the authorities this month by secretly making his way to Germany, via Vietnam and Poland, and declaring himself an exile.

Dai Qing, a journalist who wrote scathingly about the environmental impacts of the massive Three Gorges Dam, has described the indignities of having her phone calls monitored. Once when she was invited to a meeting with writers at the American embassy, a security official — tipped off by monitoring her phone calls” arrived in her living room with a warning that disobedience would lead to even more draconian surveillance “including a carload of police parked outside her Beijing home day and night. “That’s just trouble for everyone,” she said the official told her apologetically.

Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist

Tiananmen Square on May 35th

Yu Hua, author of the novel “Brothers” wrote in the New York Times, “You might think May 35th is an imaginary date, but in China it’s a real one. Here, where references to June 4 “the date of the Tiananmen incident of 1989 “are banned from the Internet, people use "May 35th" to circumvent censorship and commemorate the events of that day." When "I visited Taiwan, where my book “China in Ten Words” had just been released. "Why can’t this book be published in mainland China," I was asked, "when your fiction can?" That’s the difference between fiction and nonfiction: Although both books are about contemporary China, Brothers touches on things obliquely and so slips through the net, whereas China in Ten Words, by straight talking, goes beyond the pale."Brothers does a May 35th," I explained, "and China in Ten Words is more like June 4th." To express oneself in May 35th terms is standard practice these days" in China, where there are hundreds of million of Internet and cell phone users. "It’s a big job to keep all these onliners in line, and the government’s most effective control mechanism is to designate certain words as unacceptable and simply prohibit their use on the Internet. [Source: Yu Hua, New York Times, June 24, 2011]

"I once tried to post online a literary essay of mine. Though it made no reference whatsoever to politics, an error message kept popping up. Innocently, I assumed I must have miswritten a character or two, and marveled that technology could detect typos so easily. But after careful proofreading and revision of the odd phrase here and there, that frosty error message continued to appear. Finally I realized that the text had violated several taboos. Though widely scattered in different paragraphs, the offending words left the automated censors with little doubt that I was indulging in political dissent. We have no way of knowing how many words have been blacklisted, or which once-banned words can now be used. Sometimes you can manage to avoid all the taboos and post your opinion, but if it is couched in too explicit an idiom, it will get deleted almost right away.

"So we adapt. With the Chinese government so bent on promoting a "harmonious society," Internet users slyly tailor the phrase for their own purposes. If someone writes, "Be careful you don’t get harmonized," what they mean is "Be careful you don’t get shut down" or "Be careful you don’t get arrested." Harmonize has to be the word most thoroughly imbued with the May 35th spirit. Officials are aware, of course, of its barbed meaning on the Internet, but they can hardly ban it, because to do so would be to outlaw the "harmonious society" they are plugging. Harmony has been hijacked by the public.

Such is China’s Internet politics. Practically everyone has mastered the art of May 35th expression, and I myself am no slouch. I’ve had a go at broaching freedom-of-expression issues. I once posted an article referring to a talk I gave in Munich. The post said: "I was asked: “Is there freedom of expression in China?” “Of course there is,” I replied. “In any country,” I went on, “freedom of expression is relative. In Germany you can curse the chancellor, but you wouldn’t dare curse your neighbor. In China we can’t curse our premier, but we’re free to curse the guy next door.” "

On the concentration of power in China, I wrote: "In Taiwan I told a reporter, “You need to wear gloves when you shake hands with politicians here, because they are always out canvassing and shaking hands with people. You don’t need gloves on the mainland, because our politicians never have to press the flesh. You won’t find many germs on their fingers." Since the first remark seems to emphasize that everything is relative and the other appears to focus on matters of hygiene, both were posted on the Internet without incident. My readers know what I’m getting at.

Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist

I have always written much as I please in the May 35th mode, and for that I have the fictional form to thank, since fiction is not overtly political and by its nature lends itself to May 35th turns of phrase. Writing in the June 4th mode, as I did in China in Ten Words, was a departure from my normal practice. The question asked most often in Taiwan was, "If you had an 11th word to describe China, what would it be?" "Freedom," I answered. What I meant by that, of course, was not the familiar June 4th sort of freedom, but this more recondite May 35th kind.

Image Sources: Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist, Global Times Chinese: photo.huanqiu.com

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021