WANG MENG

at Frankfurt in 2009 Wang Meng is perhaps the most famous living writer in China, with his own personal struggles echoing those of his homeland. He was born in Beijing in 1934. During his middle school years, he was introduced to communist ideology and in 1949 officially joined the Communist Youth League. His first novella, “A Young Man Comes to the Organizational Department,” (1956) was criticized for harboring bourgeois sentiments. This could have easily ended his career or worse, but Chairman Mao intervened, praising the book.[Source: Jianying Zha, The New Yorker, November 8, 2010]

In 1963, after falling out with the Mao regime Wang was sent to Xinjiang Province to be "reformed" through labor. It was largely during this period of hardship and time spent among local Uighurs that he accrued much of the experience that would later become the material for some of his best short stories and novels. Wang served as China's Minister of Culture from 1986 to 1989. Jianying Zha wrote in The New Yorker that at seventy-six he was a ‘short, trim man with black-rimmed glasses and a full head of salt-and-pepper hair.”

“Zhebian Fengjing, a novel that Wang Meng first began writing during his time in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region's rural areas during 1960s and 1970s and finished in 2013 at age 80, won Wang his first Mao Dun prize in 2015. [Source: Global Times, August 16, 2015],

See Separate Articles: CULTURE AND LITERATURE factsanddetails.com; CONTEMPORARY CHINESE LITERATURE factsanddetails.com ; JIN YONG AND CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FICTION factsanddetails.com ; LITERATURE AND WRITERS DURING THE MAO ERA factsanddetails.com CULTURAL REVOLUTION FILM AND BOOKS factsanddetails.com ; ACCLAIMED MODERN CHINESE WRITERS factsanddetails.com ; MO YAN: CHINA'S NOBEL-PRIZE-WINNING AUTHOR factsanddetails.com YU HUA factsanddetails.com ; LIAO YIWU factsanddetails.com ; YAN LIANKE factsanddetails.com ; POPULAR MODERN CHINESE WRITERS factsanddetails.com ; POPULAR AND ACCLAIMED BOOKS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SCIENCE FICTION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE SCIENCE FICTION WRITERS factsanddetails.com ; MODERN POETRY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; WRITERS OF CHINESE DESCENT: AMY TAM, HA JIN, YIYUN LI AND GAO XINGJIAN factsanddetails.com ; PUBLISHING TRENDS AND MODERN BOOK MARKET IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; INTERNET LITERATURE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; POPULAR WESTERN BOOKS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; WESTERN BOOKS ABOUT CHINA factsanddetails.com ;

Modern Chinese Writers and Literature: MCLC Resource Center mclc.osu.edu ; Modern Chinese literature in translation Paper Republic paper-republic.org

Wang Meng’s Early Life

“Wang Meng was born in 1934, in Beijing, to parents who had arrived from a rural backwater in Hebei province, Jianying Zha wrote in The New Yorker. “When he was three, the Japanese invaded China and occupied the city, and Wang remembers having to bow to the bayonet-wielding Japanese guards at the city gates. His father, who had studied in Beijing and Japan, was enamored of all things modern and Western. A college teacher and a dreamy idealist, he was prone to grand speeches yet was incompetent in practical matters or office politics. As his career foundered, his large family struggled with debt and hunger. The household wasn’t exactly tranquil: during fights, Wang Meng’s widowed aunt would pour a pot of hot green-bean soup onto his father, and his father would get drunk and pull down his pants to embarrass the women.”

“Wang was a brilliant student, who won essay and debate competitions, along with tuition waivers. His teachers loved him. But secretly he was reading leftist books and becoming enthralled by radical ideas. His early political inclinations, he joked later, were revealed in a third-grade poem: If I were a tiger, I would devour rich people.”

Wang Meng in the Early Mao Years

‘soon, Communists recruited him, and he set to work as a middle-school agitator,” Jianying Zha wrote in The New Yorker. “He was barely fourteen when the Party accepted him as a full-fledged member. A year later, the Party took over China. “From this day on, the Chinese people have stood up!” Mao Zedong declared in Tiananmen Square as the nation rejoiced in October of 1949.The euphoria of the first days of the People’s Republic is among the dearest of Wang’s memories. He was elated by the passionate rallies, the parades, the comradely meetings and songs. He marvelled at how, within a week, Beijing cleaned up its gigantic garbage dump, a notorious problem in the old capital. The revolution, he believed, had swept away the degenerate old way of life that trapped his parents and kept China backward.” [Source: Jianying Zha, The New Yorker, November 8, 2010]

“Wang, still in his teens, was assigned to a district branch of the Communist Youth League. Always drawn to literature, he spent a full year working on a novel?a lyrical portrait of a group of radicalized teen-agers, romance mixing with innocent passion for the revolution’that ended up stuck with editors amid rounds of revision. But his first novella, “A Young Man Comes to the Organizational Department,” caused an uproar when it was published, in 1956, with its unflattering portrayal of Party officials. In the newspapers, apparatchiks accused Wang of harboring unhealthy skepticism and bourgeois sentiments. Given the temper of the time, Wang’s budding career could easily have been destroyed.”

Then something extraordinary happened: Chairman Mao learned of the controversy and intervened. At a Central Party Committee meeting, Mao praised Wang’s novella as a work “against bureaucracy.” Mao had always worried about the erosion of revolutionary fervor by bureaucratization. “I don’t know Wang Meng, but his critics don’t convince me,” Mao said about the obscure twenty-two-year- old. “Bureaucracy doesn’t exist in Bejing? I support anti-bureaucracy. Wang Meng has literary talent.”

Mao’s words bestowed not only the highest political protection’the attacks ceased---but also instant fame. Wang’s luck had turned, it seemed. Soon he was married, to Cui Ruifang, a young woman he had met through Youth League work and had courted with passionate love letters. She was a year older than him, and had great faith in his literary abilities.

Anti-Rightist Movement

Wang Meng Labeled a Rightist

“The political reprieve was short-lived,” Jianying Zha wrote in The New Yorker. “A few months later, Mao launched the Anti-Rightist campaign. In the ensuing frenzy, half a million people were denounced and sent to labor camps. Wang proved too minor a figure to be worthy of the Chairman’s continued attention. Stripped of his Party membership, he was sent to a mountainous farm outside Beijing. There, for the next four years, he did menial labor during the day and participated in ‘self-criticism meetings” in the evenings.” [Source: Jianying Zha, The New Yorker, November 8, 2010]

“Most of the “Rightists” were, like him, true believers and Party loyalists, and their ordeal drove many to depression, divorce, and suicide. Wang underwent a period of crushing self-doubt. He convinced himself that he deserved this retribution for the privileges he had enjoyed, and worked assiduously to redeem himself through hard labor. Carrying rocks and planting trees, he wrote later, improved his health, which had been delicate since childhood.”

“In 1962, Wang was allowed to move back to the city and to Cui. He and his wife both got teaching jobs, and, for the first time, they and their two young sons (occasional visits home had been permitted during the exile) were able to live together, albeit in a one-room apartment. Still, Wang longed for a writing career and literary recognition. He had published very little, and his fiction was criticized as overly intellectual. He knew nothing about workers and peasants, deemed to be the only worthy subject for “new literature.” Meanwhile, Mao, having broken with the Soviet Union, was constantly fingering traitors within the Party. The political climate was again becoming fraught.”

Wang Meng in Xinjiang

Xinjiang book “In the fall of 1963, Wang applied for a transfer to the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region, an area in the far west populated mostly by Chinese Muslims,” Jianying Zha wrote in The New Yorker. “He was answering the Party’s call for writers to “delve deep into the grass roots,” but the transfer would also remove him from the turbulent political center. That winter, the Wang family packed their few belongings and boarded a westbound train for the ninety-hour ride. “How long do you think we’ll be there?” Cui asked as the train pulled out of Beijing. “A few years,” Wang replied. “At the most, five years.” Their stay on the western frontier lasted sixteen years. [Source: Jianying Zha, The New Yorker, November 8, 2010]

“Xinjiang suited Wang. He marvelled at the region’s beauty: magnificent snow-capped mountains, rocky deserts, towering poplars, lakes that seemed as blue as the sky. He was charmed by the Uighurs’ approach to life---by the way peasant families grew roses even when they didn’t have enough to eat. He relished the flatbread and lamb that dominated local cuisine, was moved by the melancholy Uighur songs, and was enchanted by the ‘symphonic music” of their language. When he discovered that he was the subject of a fengsha---an official ban on a person and his work (the term literally means “seal off to kill”)---he put his energies into learning Uighur, which was rare for a Han, and won him great affection among the villagers. A daughter was born; Cui and Wang named her for Yining, the Uighur town where they lived.”

“Wang’s stories about Uighur life, a series of Chekhov-like tales written in simple, realist language, are among the most moving of his fictional works. Without narrative indulgence, they show an attentiveness to the details of ordinary life, the moody beauty of nature; the tone is of gentle comedy and black humor amid disaster. Reading them, you could feel Wang’s genuine respect for a culture and a people.”

“In 1966, Mao launched the Cultural Revolution. In Beijing and other big cities, the Red Guards ransacked homes, burned books, and beat up teachers, sometimes torturing and killing them. In Yining, Wang burned all his personal correspondence. But geography did help insulate him; the campaign had lost much of its severity by the time it reached the remote border town, and Wang was protected by his Uighur friends. An elderly peasant who sheltered him said, “Don’t worry, Old Wang, any country needs three kinds of men: the king, the courtesan, and the poet. Sooner or later, you will return to your post as a poet.”“

Wang Meng Wins Acclaim After Mao Era

“With the death of Mao, in 1976, the Cultural Revolution came to an end,” Jianying Zha wrote in The New Yorker. “Though the political climate remained uncertain, Wang began to write and circulate his stories, taking care to avoid anything politically risky. One afternoon in 1978, he was making dumplings at home when he saw his wife rushing home through the rain, waving a copy of People’s Literature, which had just arrived in the mail. “Your story is in it!” she yelled as she came inside. Wang grabbed the copy with his flour-stained hands: it was the foremost literary journal in China.” [Source: Jianying Zha, The New Yorker, November 8, 2010]

“In less than a year, Wang had regained his Party membership, and, after a quarter century of limbo, his first novel was published, to acclaim. (Later, it was the basis of a popular movie.) Then came an order of transfer from the Beijing Writers’ Association. In June, 1979, the Wangs boarded an eastbound train. A throng of Uighur and Han friends came to the station to say goodbye. When the train started moving, Cui buried her face in her hands and wept.”

“Wang received a monthly salary and subsidized housing from the writers’association. All he had to do was keep writing and publishing. The family moved into a hundred-square-foot room in a noisy building, with a washroom in the hallway and a loudspeaker blaring outside in the evenings. In the sweltering summer heat, he would strip off his shirt and, wearing only a pair of shorts, produce page after page.”

“After decades of repression, the hunger for new writing in China was tremendous. Literary journals thrived. In 1980, People’s Literature had a circulation of 1.5 million; other major literary magazines enjoyed readerships almost as robust. Wang struck a chord with his deftly turned portraits of innocents and true believers struggling to survive in a dark time. He was also becoming a savvy cultural official. A quick-witted speaker with impressive rhetorical and political skills, Wang was elected to the governing board of the Chinese Writers’Association. He pushed for more liberal policies but maintained a warm, deferential relationship with senior Party leaders. In 1985, he was elected to the Communist Party’s Central Committee.”

“Years later, when someone remarked that Wang was “a nice guy but had no achievements as a minister,” he protested, “But I lifted the ban on night clubs!” Wang was a decidedly liberal minister. He pushed for greater openness and pluralism in the arts, brought Western artists like Luciano Pavarotti and Plácido Domingo to perform in China. Yet the ferment of the late nineteen- eighties made such gestures seem pallid. Wenhua “red culture fever”---was taking hold. “Emancipating the mind” was a Party slogan at the time, but younger writers and critics took the notion much farther than officialdom ever contemplated. They had little time for Wang’s cautious meliorism. The moment belonged to the likes of Liu Xiaobo.”

Wang Meng, Servant of the State

The Tiananmen Square demonstrations filled Wang with dread. “At one point,” Jianying Zha wrote in The New Yorker, “he spent seven hours talking down his twenty-year-old daughter, after which he accompanied her to her university, and waited outside the campus gate until she persuaded her class not to join the demonstrations. While he was abroad with a delegation in Europe and Egypt, the situation rapidly deteriorated. On June 4th, the nineteen-eighties---idealistic, naïve, fragile---came to a crashing end as the tanks arrived in Tiananmen Square.” [Source: Jianying Zha, The New Yorker, November 8, 2010]

“In the post-Tiananmen years, Wang was the subject of investigations; some of his former colleagues, including his vice-ministers, distanced themselves from him. Conservative publications denounced him. With Wang newly vulnerable, hardliners pushed the idea that his “Tough Porridge” was actually a veiled attack on Deng Xiaoping, who, ostensibly retired, was still the supreme power at the time.”

After Wang gave a public lecture at the Frankfurt International Book Fair on October 18, 2009 he was asked to describe the state of literature in his country. He said, “Chinese literature is developing very quickly, and so is the readers’taste,” he said, in bland, diplomatic language. “Chinese literature is at its best of times. . . . One can say China is a big literary nation.” His remarks were greeted with derision on the Chinese Internet. The popular blogger Li Chengpeng called Wang a liar and a toady: most literary publications in China, he said, “are full of falsity and perversity, with many writers taking money from the state and creating junk and gibberish. . . . Wang Meng’s way of thinking is that of the eminent men in all fields: as long as it’s large, plentiful, and junky, everything Chinese . . . is at the best of times.” Within days, the blog post had received more than a hundred and fifty thousand hits and thousands of reader comments.

Jianying Zha wrote in The New Yorker, “The denunciations were reminiscent of a controversy that beset Wang in the early nineteen-nineties. In 1994, a young Nanjing critic named Wang Binbin published an article entitled “The Too-Clever Chinese Writer.” Many Chinese writers, Wang Binbin contended, had well-developed survival skills but lacked the courage to tell the truth when it was dangerous to do so. One of his examples was Wang Meng. Wang responded with a couple of essays, insisting that the young critic was going after famous people chiefly in order to make his name.“

Wang Meng Attacks Liu Xiaobo

Liu Xiaobo Zha wrote: “But Wang Meng’s contemptuous tone grated, especially when he attacked the literature professor turned human-rights activist Liu Xiaobo. Liu, the recipient of this year’s Nobel Peace Prize, was a brave activist during the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, and was imprisoned for a year and a half afterward. In Chinese cultural life, it was one of those moments of almost tectonic slippage, in which a fault line becomes a chasm. Wang could be caricatured as a court poet, and nothing more; his antagonist, Liu, as a passive martyr, and nothing more. The stark contrast provided blinding clarity, with an emphasis on blinding; it was false to both. Tells about Wang’s youth and childhood and his involvement in the Communist Party during the early years of the People’s Republic.” [Source: Jianying Zha, The New Yorker, November 8, 2010]

In his essay, Wang viciously mocked Liu: “About ten years ago, a black horse appeared on the literary scene; he struck a majestic posture, as though he commanded the wind and clouds and could easily force ten thousand troops to retreat; he talked the grand talk of someone who considered himself original and everyone and everything else beneath him. . . . His self-trumpeting and self-aggrandizement, his yelling and selling, have been mocked in private, but have also attracted some attention. He was even cheered on by a few youngsters who have always resented the famous and the eminent but were born too late to get a chance to put the tall paper hats on those heads and parade them at the street rallies.”

Zha wrote: “The superior tone was chilling. How could Wang, with all his privileges, attack a political prisoner who was unable to speak publicly? Many felt that Wang had sunk to character assassination. “Among young people, Wang Meng is finished,” a Beijing friend told me. Wang’s reputation among liberal intellectuals never fully recovered...Some still finds the assault unforgivable. In his mind, Wang’s act was luojing xiashi: “dropping a stone over someone’s head after he falls into a well.”

Books by Wang Meng

Wang Meng has published over 60 books since 1955, in nearly every genre, including six novels, ten short-story collections, as well as other works of poetry, prose, critical essays, criticism, reviews, lectures, autobiography, and even translations of some John Cheever stories. His works have been translated and published in 21 different languages. [Source: Jianying Zha, The New Yorker, November 8, 2010]

Wang’s his first novella, “A Young Man Comes to the Organizational Department“, caused an uproar when it was published, in 1956. The story, set in a district Party office, depicts an idealistic young cadreman much like Wang himself clashing with a range of senior Party officials, variously jaded, savvy, and corrupt. At a time when literature served essentially as Party propaganda, the unflattering portrayal of Party officials was unusual.

Wang’s second novel, “Huodong Bian Renxing“ (the title refers to a Japanese toy that changes shape when you play with it), was published. Widely considered his best novel, it was set in nineteen-forties Beijing and based on Wang’s own childhood experiences, painting a bleak picture of life in “old China.” The book depicts two parents trapped in an unhappy marriage, and their son’s mounting belief in revolution. The year after its publication, Wang became China’s cultural minister.

“Tough Porridge“ (1989) won China’s top literary prize for short fiction. Zha wrote: “It’s about a large family that has always eaten rice porridge and pickled vegetables for breakfast. The grandfather, a revered but open-minded patriarch, offers to relinquish his authority over the menu to others. When the family’s retainer of four decades takes charge, she starts skimping on ingredients and, with the money she saves, buying the grandfather ginseng royal jelly for his health. Soon, the trendy grandson is serving an all-Western breakfast, to which some family members secretly add Chinese spices, causing digestive woes. Various other reforms are attempted, including democratic voting. People start eating separately. A great-grandson goes off to work at a joint-venture company. The intellectual son and his wife move abroad. Eventually, though, they all return to the porridge breakfast, so plain and so soothing.” It was written around the time of Tiananmen Square when calls for political reform made Wang worry another Cultural Revolution might break out.

“Wang’s stories about Uighur life, a series of Chekhov-like tales written in simple, realist language, are among the most moving of his fictional works. Without narrative indulgence, they show an attentiveness to the details of ordinary life, the moody beauty of nature; the tone is of gentle comedy and black humor amid disaster. Reading them, you could feel Wang’s genuine respect for a culture and a people.”

His stories from his Xinjiang years---like the one about the time he and a Uighur friend sat by the highway and shared a bottle of liquor, drinking from a bicyclebell cup---are warm, self-deprecating, nostalgic. The message was about ethnic harmony and Han-Uighur friendship.

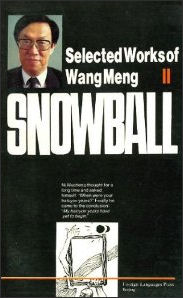

Books by Wang Meng available in English: 1) “100 Glimpses into China: Short Stories from China“ by Wang Meng, Feng Jicai, Wang Zengqi and others, translated by Xu Yihe and Daniel J. Meissner (Beijing, Foreign Languages Press, 1989); 2) “Alienation“, translated by Nance T. Lin and Tong Qi Lin (Hong Kong: Joint Publishing Co., 1993); 3) “Bolshevik Salute: A Modernist Chinese Novel“, translated by Wendy Larson (Seattle, University of Washington Press, 1989) 4) “Prize-winning Stories from China, 1978-1979“ by Liu Xinwu, Wang Meng, and others (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1981); 5) “Snowball“, translated by Cathy Silber and Deirdre Huang (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1989); 6) “The Butterfly and Other Stories“ intro. by Rui An (Beijing: Chinese Literature,1983); 7) “The Strain of Meeting, translated by Denis C. Mair (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1989); and 8) “The Stubborn Porridge and Other Stories “, translated by Zhu Hong (Schriftsteller).

Image Sources: Amazon, Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: The New Yorker, Global Times

Last updated November 2021