WRITERS OF CHINESE DESCENT BASED OUTSIDE CHINA

Maxine Hong Kingston is a Chinese- American born in 1940 in California. Her “The Woman Warrior” won the National Book Critics Award for Nonfiction in 1976. Good modern books non-Chinese of Chinese descent about China include “Spring Moon” by Betty Bao Lord, the wife of a former American ambassador to China and “Wild Swans” by Jung Chang. The Last Communist Virgin” by Wang Ping is a fine collection of stories that offer insight into Chinese culture and are well written and intriguing as stories. Wang grew up in China and has been based in New York and Minnesota.

In 2008, a Chinese writer won the Akutagawa Prize, Japan’s highest literary award,. Harbin-born Yang Yi, the award winner, come to Japan in the 1980s and has lived there ever since. Her Japanese-language novel “Toki ga Nijimu Asa” (“Morning when Time Blurs”) is about a student idealistic student during the time of Tiananmen Square.

Modern Chinese Writers and Literature: MCLC Resource Center mclc.osu.edu ; Modern Chinese literature in translation Paper Republic paper-republic.org ; Wang Shou Wikipedia article on Wang Shou Wikipedia ; Shanghai Baby Book Reporter Review bookreporter.com ; Gao Xingjian Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Nobel Prize site nobelprize.org ; BBC Report bbc.co.uk ; Ha Jin Random House randomhouse.com ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Book Browse bookbrowse.com ; Book Reporter bookreporter.com ; Amy Tan Amy Tam.net amytan.net ; Academy of Achievement biography achievement.org ; Anniina’s Amy Tam Page luminarium.org ;

See Separate Articles: CULTURE AND LITERATURE factsanddetails.com; CONTEMPORARY CHINESE LITERATURE factsanddetails.com ; JIN YONG AND CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FICTION factsanddetails.com ; LITERATURE AND WRITERS DURING THE MAO ERA factsanddetails.com CULTURAL REVOLUTION FILM AND BOOKS factsanddetails.com ; ACCLAIMED MODERN CHINESE WRITERS factsanddetails.com ; MO YAN: CHINA'S NOBEL-PRIZE-WINNING AUTHOR factsanddetails.com YU HUA factsanddetails.com ; LIAO YIWU factsanddetails.com ; YAN LIANKE factsanddetails.com ; WANG MENG factsanddetails.com ; POPULAR MODERN CHINESE WRITERS factsanddetails.com ; POPULAR AND ACCLAIMED BOOKS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SCIENCE FICTION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE SCIENCE FICTION WRITERS factsanddetails.com ; MODERN POETRY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; PUBLISHING TRENDS AND MODERN BOOK MARKET IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; INTERNET LITERATURE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; POPULAR WESTERN BOOKS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; WESTERN BOOKS ABOUT CHINA factsanddetails.com ;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Joy Luck Club” by Amy Tan Amazon.com; “The Kitchen God's Wife” by Amy Tan Amazon.com; “Soul Mountain” by Gao Xingjian Amazon.com; “Waiting” by Ha Jin Amazon.com; “A Thousand Years of Good Prayers: Stories” by Yiyun Li Amazon.com; “The Vagrants” by Yiyun Li Amazon.com;

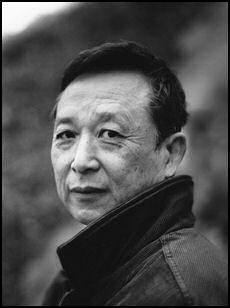

Nobel-Prize-Winner Gao Xingjian

The Paris-based playwright and novelist Gao Xingjian won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2000. It was the first Nobel literature prize for a someone born in China. Only a few intellectuals knew who he was before he won the prize. Only after he won were his works translated into English. In China he is mostly ignored. The government regards him as French. Even after he won the prize he remained unknown to most ordinary Chinese.

The New York Times described Gao as "a small, tidy figure with crinkly smiling eyes." Gao said the Nobel prize was "something that falls on you from the sky like a miracle. It's a total surprise...While this prize guarantees my independence. I don’t think it will make my work better-known in China."

Gao was born in eastern Jiangxi Province in 1940, while bombs were exploding during the Japanese occupation of China. At the age of 15 he had a dream that dramatically changed him. He told the Observer, "I was sleeping with a marble woman. She was beautiful and cold — a statue that had fallen into the grass, and I was lost in an exuberant freedom. It was that freedom, which we call decadent, that brought me to France.”

Gao was born in eastern Jiangxi Province in 1940, while bombs were exploding during the Japanese occupation of China. At the age of 15 he had a dream that dramatically changed him. He told the Observer, "I was sleeping with a marble woman. She was beautiful and cold — a statue that had fallen into the grass, and I was lost in an exuberant freedom. It was that freedom, which we call decadent, that brought me to France.”

During the Great Leap Forward in the 1960s his mother drowned after being sent to the countryside to do forced labor. Gao began writing seriously around that time. His works angered the Communist. During the Cultural Revolution his wife denounced him and he was forced to burn "kilos and kilos" of his works out of worry about being imprisoned. He did hard labor in the fields for six years.

Gao was allowed to write again in 1979 but not for long. In 1983 his play “Bus Stop” was condemned, and after that he was continuously hounded and harassed. After the publication of “Fugitives”, a play set against the backdrop of Tiananmen Square, he was declared a persona nongrata and his work was banned.

Gao Xingjian, France and China

In 1987, Gao left China for Paris and has lived in exile in France ever since. "I love Paris," he said. "It's the best city in the world for artists." After the Tiananmen Square crackdown in 1989, his apartment was seized by authorities. He became a French citizen in 1998. He never returned to mainland China.

At the time he won the Nobel prize, Gao lived in a two-room apartment on the 19th floor of an apartment block in Bagnoley, a tough suburb east of Paris. He said he spends 16 hours a day writing and painting. He enjoys listening to Mozart and Messiaen. He doesn't associate much with the Chinese community in France On his profession, he said, "Writing eases my suffering...Writing is my way of reaffirming my own existence."

Beijing criticized Gao’s Nobel Prize, saying it was given for "ulterior political motives." It said Gao’s writing is “very, very average.” After winning the Nobel Prize, Gao made visits to Taiwan and Hong Kong,.

Gao avoids talking about politics and has never been very political anyway. The Chinese government reportedly doesn't like him because of his lack patriotism and his focus on ordinary people. He does occasionally offer his opinion on Chinese society. He told an Australian newspaper, “Chinese people are too confined by their own culture. As far as I’m concerned, Chinese culture in general is meaningless...Too much emphasis on identity can become talk without real meaning and it can easily lead to nationalism. There is only identity that is beyond doubt and that is that you are an individual.”

Gao avoids talking about politics and has never been very political anyway. The Chinese government reportedly doesn't like him because of his lack patriotism and his focus on ordinary people. He does occasionally offer his opinion on Chinese society. He told an Australian newspaper, “Chinese people are too confined by their own culture. As far as I’m concerned, Chinese culture in general is meaningless...Too much emphasis on identity can become talk without real meaning and it can easily lead to nationalism. There is only identity that is beyond doubt and that is that you are an individual.”

On his relationship with the Beijing government Gao told the New York Times in 2012: “I have no interest in that. I’ve been away from mainland China for 24 years. China is far away from my real life. My contribution to Chinese literature is finished. Now I live in the West and my concern is Europe, which is undergoing a crisis.” He also dismissed his usual tag of writer-in-exile. “I’m lucky to have had three lives: The first was in China; the second in exile; and the third in France,” he said. “I am a French writer with a French passport. I am a citizen of the world. For me, national borders are meaningless.” [Source: Joyce Hor-chung Lau, New York Times, March 1, 2012]

Gao Xingjian's Works

Early in his life Gao was influenced by playwrights like Samuel Beckett and Antonin Artaud and the surrealist Eugene Ionesco. In awarding him the Nobel Prize The Swedish Academy said he produced "an oeuvre of universal validity, bitter insight and linguistic ingenuity" and explores "the struggle of the individual to survive the history of the masses."

Joyce Hor-chung Lau wrote in the New York Times: Gao’s plays include “Absolute Signal,” “Bus Stop” and “Wild Man.” “Of Mountains and Seas” is an irreverent retelling of ‘shanhaijing,” an ancient text that includes the classic Chinese creation myth. Nu Wa, a wailing banshee of a goddess, expels the first humans from her bowels. They are a dirty, noisy, vulgar lot, dressed in rough canvas clothes, with distorted masks held over their faces. They fight and dance and copulate, to bear even more dusty offspring. Local viewers would recognize elements from Chinese mythology: The handsome Yi the Archer shoots down 9 of the 10 suns scorching the earth. His wife, the lovely Chang E, wishes for immortality and rises up to the moon, in a legend still celebrated during the Mid-Autumn Festival. There is a universality to the symbolism: the flawed woman eating the forbidden fruit, the punishing deluge cleansing the bickering mortals below, a god who becomes a civilization’s first emperor. [Source: Joyce Hor-chung Lau, New York Times, March 1, 2012]

Gao receives Nobel prize

“Bus Stop” (1983) has been described as a "kind of Zen theater of the absurd." It was condemned by the Communists as "pernicious.” “Fugitives” is his most overtly political play. It is set during Tiananmen Square. The short stories “The Temple” and “The Accident” were published in the New Yorker. The former is a sweet story about the innocent happiness of Chinese newlyweds. The former describes the reaction by bystanders to a man killed when a bus hits his bicycle.

The novel “Soul Mountain” (1989) is regarded as Gao's masterpiece. The Swedish Academy called it "one of those singular literary creations that seems impossible not to compare with anything but themselves." Its name is inspired by a 10-month walking tour Gao took along the Yangtze River.

Much of the appeal of the work is lost in translation. After reading the first translation released in the United States, Paul Gray wrote in Time, "Reading “Soul Mountain” in this version is a frustrating experience chiefly because of the sense that there must be more to it than this...It is in a strange and often irksome form of English. Run on sentences sprawl...Gao...is regarded as a master of the Chinese language. Perhaps that skill cannot be completely conveyed in a translation, but a better use of English might have helped." One sentence goes: "I hadn't originally intended to do any reading, what if I did read one book more or one book less, whether I read or not wouldn't make a difference, I'd be waiting to get cremated." There are also sentences like "Many pretty young girls have also suicided."

Wolfgang Kubin, the respected Sinologist and professor at the University of Bonn, wrote. “I have never read deeper condemnation of a Chinese writer than that of Gao Xingjian in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, first in 2000 and then last year. But, I have to confess, I'd prefer dying to writing Soul Mountain and winning the Nobel Prize for Literature for it, as the novel is a real shame.”

Amy Tam

Amy Tan is a San-Francisco-based Chinese-American writer who bestsellers about life in China and life for Chinese -Americans in the United States. Her books — “The Joy Luck Club” (1989), “The Kitchen God's Wife” (1991), “The Hundred Secret Senses” (1995), “The Bonesetter's Wife” (2001), “Opposite of Fate” — often explore the relationships between Chinese-born mothers and their yuppie Chinese-American daughters and mystical aspects of Chinese culture. “The Joy Luck Club” was made into a 1993 film directed by Wayne Wang.

Tan was born in Oakland, California in 1952 to Chinese-born parents. When she was 15, her father and 16-year-old brother died within six months of each other, both of brain tumors. After this she said her mother held a knife to her throat "to kill me first and then kill herself." Her mother’s experience with tragedy was even more direct. In addition to losing her husband and son, she lost her mother (Amy’s grandmother), who committed suicide by swallowing a bottle of opium after she had been raped and forced to be the concubine for a rich man. .

Tan’s fiction and her life often seems centered around the relationship between mother and daughter. Tan’s real life mother, Daisy, grew very morbid about the tragedies that happened to her and was shy about expressing her feelings to her daughter. When Tan was six, her mother dragged here to the funeral of one of her playmates and pointing at the body said, “This what will happen to you if you don’t listen to your mother.” Daisy died in 1999 at te age of 83.

Amy Tam’s Parents and Half Sisters in China

Kenan Christiansen wrote in New York Times: “In 1949, Amy Tan’s mother boarded one of the last ships heading from Shanghai to San Francisco before “China became Red China and the bamboo curtain descended.” There, her mother reunited with her husband and the couple relocated to Oakland, where a couple of years later she was born. As a child, she knew little more about China than an “American pastiche of stereotypes,” and that some of her family had been lucky enough to make it out, while others had not. For years she organized her thinking around those divisions, until revelations about her family and the country her parents fled broke them down. [Source: Kenan Christiansen, New York Times, January 24, 2014]

Amy Tan and her mother

Tam told the New York Times: My parents considered themselves lucky that they were able to leave before 1949. Other family members were not quite as lucky and wound up in Formosa — that’s what we called Taiwan in those days. They sent us letters that described hard work and lack of proper food, hygiene and clothing. In their photos, they looked weathered and shiny with sweat. We received no letters from China and prayed for those silent ones whose whereabouts were unknown. If America was heaven, Formosa would be limbo, and China would be hell. [Source: Kenan Christiansen, New York Times, January 24, 2014]

When I was 16, after my father died, my mother told me that she had been married to another man in Shanghai before she met my father. I could hardly comprehend this stunning news, when she added she also had three daughters in China. She did not explain why they were in China, whereas she was in California. Years later she would only say that her previous husband had been a bad man. If I pressed her she would have said that I did not understand because I was an American. That was her typical lament when I did not seem to appreciate the tragedies of her life, like the suicide of her mother, which left her alone — abandoned, really — at the age of 9. She showed me their photos. The middle daughter, Jindo, was beautiful. She resembled my mother. She also fit the stereotype of peasants I had imagined in childhood. She wore a conical hat and farmer’s clothing, and she was standing next to a rice field. That could have been my life.

“In 1979, after a 30-year separation, my mother went to visit her three daughters. Jindo lived in a village of rice farmers. She had married a barefoot doctor, and they and several comrades served my mother a modest feast in a shack whose walls were lined with newspaper to keep out the cold.

Amy Tam and China

Tan’s novel “The Valley of Amazement” (2014) about how her relationship with China changed over time. Kenan Christiansen wrote in New York Times: “. As a child, Tam knew little more about China than an “American pastiche of stereotypes,” and that some of her family had been lucky enough to make it out, while others had not. For years she organized her thinking around those divisions, until revelations about her family and the country her parents fled broke them down. [Source: Kenan Christiansen, New York Times, January 24, 2014]

Tam told the New York Times: Growing up in the 1950s and 1960s, I thought of China as a prison that everyone wanted to escape.” “After he mother told her about her half-sisters in China, Tam said: “China was no longer an invisible jail. I now imagined myself living there, wearing a conical hat and writing letters late at night to my mother, in beautiful Chinese calligraphy like that of my newfound sisters. “I dream every day you will return,” Jindo had written her. “When you do, my happiness will be restored.”

On her first visit to China, Tam said: “In 1987, my mother, husband and I went together. We stepped out of the plane into an airport painted toothpaste green. I had assumed I would blend in with the masses. Instead, I was surrounded by locals who gawked at me and made open comments about my outlandish purple clothing.

“These days, I go about once a year. The most gleamingly modern airports I’ve been to are in China. The coolest and most technologically challenging hotel I’ve ever stayed in is in China. The most tricked-out hair salon I’ve been to is in China. The worst pollution I’ve endured is in China. I keep going back for more of the most. Not everyone wants to escape anymore. In fact, it is more often the case that Chinese students go to the U.S. to study and return to start companies and make millions.

On how China has changed, Tam said, “I look at China not as a land of burdens and debt but the land of origin that gave our family its improbable history. I once traveled with Jindo on a long ferry ride to a mansion, the one on the island near Shanghai, where my mother grew up, where Jindo also grew up. I listened to her stories about working in the rice fields, where she wore the conical hat and danced and yelled as she pulled leeches off her calves. She eventually told me what happened to her after our mother left, about the abuse she suffered at the hands of her father’s concubine. As Jindo re-enacted the past, she flung her arms and beat her chest, and it must have appeared that we were having a violent argument.

““It was not right,” she said repeatedly, and she meant what her stepmother did to her, and also what her father did to our mother, and what my mother did in choosing to be with a lover rather than with her three daughters, and then in marrying that lover and having three children by him, one of them a daughter, who was sitting next to her, listening to her cry.

Bonesetter's Daughter Opera

“The Bonesetter’s Daughter“, Amy Tan’s best-selling 2001, shifts from modern-day San Francisco to China and Hong Kong in the 1930s and “40s, and from this world to the next, as it tells the story of three generations of women: Precious Auntie, who lived and died in old China; her daughter, LuLing, a Chinese immigrant facing life’s twilight in San Francisco; and Ruth, LuLing’s American-born daughter, with whom she has long had a challenging relationship. The women are descendants of a Chinese bonesetter who healed patients with a secret ingredient that has bound the family together for a thousand years: dragon bones.

In The Bonesetter’s Daughter dragon bones symbolize the genetic links and secret histories that bind the three women, even offering a cure of a sorts when the secrets involving the bones are revealed. The idea to turn this multilayered novel into an opera did not come from its author.

An opera based on “The Bonesetter’s Daughter“, with music by composer Stewart Wallace and a libretto written by Tan, was staged by the San Francisco Opera and Chorus with an eclectic mix of talent, including acrobats, dancers and traditional opera performers from China and a strong cast of singers and musicians from China. [Source:Sheila Melvin, New York Times, August 28, 2008]

Ha Jin

Ha Jin (born 1956) is an American-based Chinese writer born in Liaoning, China. He won the PEN/Hemingway prize in 1996 for his first English language collection of stories “Ocean of Words”; received the Flannery O’Conner award in 1996 for his second collection of stories “Under the Red Flag” in 1996; won the National Book Award for his English language novel, “Waiting”; and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 2005 with third novel “War Trash”.

John Updike wrote in the New Yorker, “His prize-winning command of English has few precedents, notably Conrad and Nabokov, but neither made the leap out if a language as remote from the Indo-European group, in grammar and vocabulary in scriptural practices and literary tradition, as Mandarin."

Ha Jin was born in 1956 to a pair of military doctors. He volunteered for the PLA at age 14 and served 5½ years near the northeast border with Russia. He began taking a keen interest in reading in the Cultural Revolution when the only book that was available was “The Little Red Book”. At Heilongjiang University in Harbin he was assigned English as a major even though it was his last choice, After receiving a master’s degree in American literature from Shandong University he came to the United States to do graduate work at Brandeis University.

Ha Jin moved to the United States in the mid-1980s. His plan to return to China and become a poet and translator were squashed by Tiananmen Square in 1989. In 1993 Ha Jin was hired as an instructor in poetry at Emory University. He is now a professor at Boston College. Although he writes beautifully he still has trouble with spoken English. His style has been called “deadpan hyperrealsim.”

Ha Jin's Books

“Waiting” is Ha Jin’s first English-language novel. It is about a doctor who waits 18 years to get a divorce so he can marry the woman he loves. Much of it set during the Cultural Revolution. Critics have compared the book with works by Russian masters like Gogol and Chekhov. “Waiting” was attacked in the Chinese media and Ha was accused of being anti-Chinese. The book was finally published in China in 2002.

Updike wrote, “”Waiting” is impeccably written, in a sober prose that does nothing to call attention to itself and yet capably delivers images, characters, sensation, feelings, and even, in a basically oppressive static situation, bits of comedy and glimpses of natural beauty...not a word of Ha Jin’s hard-won English seems out of place or wasted.”

Other books by Ha Jin include his second novel “The Crazed” (2002). “War Trash” is about the horrors of a Korean prison camp. “A Free Life” (2007) was his first novel set in the United States. The New York Review of Books called it “a high achievement indeed.” The Los Angeles Times Book Review described it as “achingly beautiful.” The Washington Post said the novel was “too long” and “lacked momentum.”

Yiyun Li

Yiyun Li, like Ha Jin, is a Chinese writer who writes in English for an American audience. Born in Beijing in 1972, she came to the United States in 1996 to study immunology in Iowa and began writing to improve her language skills and later turned to writing stories as a means of expression.

Li has been hailed as one of the finest writers of short fiction. Her stories and essays have been widely published. Her debut collection, “A Thousand Years of Good Prayers” (2005) won the Frank O'Connor International Short Story Award, PEN/Hemingway Award, “Guardian’First Book Award and California Book Award for first fiction. It was also shortlisted for Kiriyama Prize and Orange Prize for New Writers. She was selected by “Granta” as one of the 21 Best Young American Novelists under 35. Her first novel, “The Vagrants”, was published in 2009, to great acclaim. She teaches at the University of California and was a 2010 recipient of a MacArthur “genius grant” fellowship.

Yiyun’s success not only brought her notoriety and money but also helped her secure a green card, which she desperately wanted after her application for one based on “extraordinary ability” was rejected. She s now an assistant professor at the University of California in Davis. She told Newsweek, “I just can’t live in China. Not because I don’t love my country. I just can’t write in China. I can’t explain it. Its like, no matter how much you love your mother, you have to live anyway.”

Vagrants and Other Works by Yiyun Li

Yiyun Li's 2005 debut story collection A Thousand Years of Good Prayers earned her comparisons with Chekhov and Alice Munro. In 2010 she released a story collection called “Golden Boy, Emerald Girl“.

“The Vagrants“ (Random House, 2009) is thought-provoking novel about two women in modern China. Set in China in the 1970s and early 1980, it follows a bunch of misfits as they try to get ahead and eek out an existence in the weird and grim transition from Maoism to capitalism. To get ahead the characters turn to crime and betrayal. For entertainment they attend public executions. The kind of sentiments and drives hat propel heroes forward in Hollywood films only lands them in trouble in this books. On how to how to succeed in such a world a father tells his 7-year-old son: “If your heart is hard enough to eat your mother and your wife, nothing can beat you in life.”

The main character, 19-year-old Bashii, spends his time searching riverbanks for infants and falls in love with a 12-year-old after educating himself about female anatomy from a corpse he found. Other characters included a child who betrays his father and a television announcer willing to sacrifice his family for his ideals.

Guardian Review of The Vagrants

The Vagrants is set in China in China in the late 1970s when the Democracy Wall Movement rocked Beijing. It “draws heavily on the art of the short story as it follows a disparate group of citizens of the industrial town of Muddy River over three months in 1979. It is three years since the death of Mao, and in the capital there are glimmers of hope for those who dream of greater freedom - a democratic wall has been erected, where people can express their views of the Party without fear of reprisals. But in Muddy River, provincial officials are nervous that rumors from the capital will lead to unrest.” [Source: Stephanie Merritt, The Guardian, February 15, 2009]

Based on real events, Li's story begins on the day of a public execution. A young woman, Gu Shan, a convicted counter-revolutionary, is to be shot for criticising the party in her prison journals. Among the crowd gathered to witness the denunciation ceremony are a number of characters whose fates are bound with invisible threads. They include Nini, a deformed girl, and Kai, a model citizen who has made an advantageous marriage to a high-ranking official, but yearns to break the bounds of her stiflingly correct life.

After the ceremony, Nini witnesses the prisoner rushed from the stadium and bundled into an ambulance, but it is Kai who learns that her former classmate's execution was expedited so that Shan's kidneys could be transplanted to a party official. Inspired by reports of the democratic wall, Kai organizes a peaceful protest, demanding an investigation into the execution.

After the ceremony, Nini witnesses the prisoner rushed from the stadium and bundled into an ambulance, but it is Kai who learns that her former classmate's execution was expedited so that Shan's kidneys could be transplanted to a party official. Inspired by reports of the democratic wall, Kai organizes a peaceful protest, demanding an investigation into the execution.

These are the bones of the novel, but its course is as meandering as the Muddy River itself; through small details, Li creates an unsparing picture of life under a totalitarian regime. Poverty, hunger and fear are the forces that shape these lives; school choirs sing songs such as “Without the Communist Party We Do Not Have a Life”, but people live in a state of mistrust and a mother's best advice to her son is: “Always follow what's been taught and you won't make a mistake.”

It is not giving too much away to reveal that Kai has misread the mood of the country. The novel's ending is truly chilling and carries echoes of other, similar stories, as neighbors rush to spill names to the secret police in the hope of saving themselves.

Because The Vagrants is a series of linked vignettes rather than a linear narrative, some patience is required of the reader. Although Li has a story-writer's talent for endowing characters with a full life in a few paragraphs, some remain tantalisingly sketchy. But The Vagrants is an important novel, a requiem for forgotten victims and a careful, honest portrait of what China has been, even as it emerges from the shadow of those years.

Image Sources: University of Washington, Ohio State University, Amazon.com, Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html , Wikipedia, Achievement.org, Landberger posters

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021