SERIOUS MODERN CHINESE WRITERS

Mo Yan won the 2012 Nobel Prize for literature. He wrote “Red Sorghum”, which was made into a famous movie by Zhang Yimou (See Film), and “Big Breasts & Wide Hips”, both of which have been translated into English by Howard Goldplatt. Mo Yan was born in 1955 in a peasant family in northern China and is known for his colorful imagery, magical realism style and historical references. See Separate Article MO YAN: CHINA'S NOBEL-PRIZE-WINNING AUTHOR factsanddetails.com ;

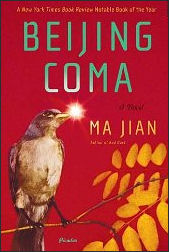

Noteworthy modern activist writers include Ma Jian, known for speaking up and offering an independent, critical voice; Liu Xiaobo, a Nobel Peace Price jailed for many years for his Tiananmen Square and pro-democracy activism; and the Tibetan writer Woeser and her Chinese husband Wang Lixiong. “Zhang Xianliang was known for breaking the Chinese taboo on sex in literature with his works after the Cultural Revolution. Good modern books about China include “Chinese Lives” by Zhan Xinxin and “Life and Death in Shanghai” by Nin Cheng (about the struggle to survive in the Cultural Revolution).

Of writers active today, the biggest names, such as Yu Hua and Su Tong, are “60-hou”, or “post-60ers — who were born in the 1960s but “mostly achieved fame while in their 30s.” Another batch of writers favored by the mainstream media are the “80-hou”, especially Han Han and Guo Jingming. [Source: Raymond Zhou, China Daily, February 21, 2008]

Yan Lianke is one of China’s most popular novelists and a former propaganda writer for the PLA. Among his books are “Enjoyment”, about Chinese officials who buy Lenin’s copse from Russia and bring it to their hometown as a tourist attraction and “Save the People”, about a woman who gets off sexually when her lover rips of passage of “The Little Red Book” and breaks her husbands Mao icons.

Most of the winners of the Mao Dun and Xu Lun Literature Awards. China's two main literary prizes, have not been translated to English and if they have the translating often takes place some time after the awards have been given. The five winners of the 9th Mao Dun Literature Prize in 2015 were Ge Fei (Jiangnan Trilogy), Wang Meng (Zhebian Fengjing), Li Peifu (Shengming Ce), Jin Yucheng (Fan Hua) and Su Tong (Huangque Ji) took home prizes this year.Among the five winning works, Jin's Fan Hua (Blooming Flower), written in the Shanghai dialect, has been regarded as a "black horse" in literature circles since its publication in 2012. [Source: Global Times, August 16, 2015],

See Separate Articles: CULTURE AND LITERATURE factsanddetails.com; CONTEMPORARY CHINESE LITERATURE factsanddetails.com ; JIN YONG AND CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FICTION factsanddetails.com ; LITERATURE AND WRITERS DURING THE MAO ERA factsanddetails.com CULTURAL REVOLUTION FILM AND BOOKS factsanddetails.com ; MO YAN: CHINA'S NOBEL-PRIZE-WINNING AUTHOR factsanddetails.com YU HUA factsanddetails.com ; LIAO YIWU factsanddetails.com ; YAN LIANKE factsanddetails.com ; WANG MENG factsanddetails.com ; POPULAR MODERN CHINESE WRITERS factsanddetails.com ; POPULAR AND ACCLAIMED BOOKS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SCIENCE FICTION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE SCIENCE FICTION WRITERS factsanddetails.com ; MODERN POETRY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; WRITERS OF CHINESE DESCENT: AMY TAM, HA JIN, YIYUN LI AND GAO XINGJIAN factsanddetails.com ; PUBLISHING TRENDS AND MODERN BOOK MARKET IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; INTERNET LITERATURE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; POPULAR WESTERN BOOKS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; WESTERN BOOKS ABOUT CHINA factsanddetails.com ;

Modern Chinese Writers and Literature: MCLC Resource Center mclc.osu.edu ; Modern Chinese literature in translation Paper Republic paper-republic.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS AND FILMS: “Raise the Red Lantern: Three Novellas” by Su Tong Amazon.com; “Raise The Red Lantern” (the Film) Directed by: Zhang Yimou Amazon.com; “The Boat to Redemption: A Novel” by Su Tong and Howard Goldblatt Amazon.com; “Golden Age: A Novel” by Wang Xiaobo, Brian Nishii, et al. Amazon.com; “Pleasure of Thinking: Essays” by Wang Xiaobo, Yan Yan - Translated by, et al. Amazon.com; “Red Dust: A Path Through China” by Ma Jian Amazon.com; “China Dream” by Ma Jian, David Shih, et al. Amazon.com; “Beijing Coma: A Novel” by Ma Jian and Flora Drew Amazon.com

Su Tong: Author of Raise the Red Lantern

Su Tong is known for dark, provocative works which have been popular but have sometimes put him at odds with the authorities. His most famous work is the novella “Wives and Concubines” (1989), which was adapted into the art-house favorite and Oscar-nominated film, “Raise the Red Lantern” by Chinese director Zhang Yimou. He has written six novels including “Rice” and “My Life as Emperor”. The latter offers insight into ruthless Imperial power in all its bloody glory. Several of his books have been translated into English by Howard Goldplatt.

Su Tong burst onto the Chinese literary scene in the mid-eighties. Since then, his prolific and provocative work — seven novels, a dozen novellas, over 120 short stories, with translations available in a dozen languages. He won the 2009 Man Asian Literary Prize for his novel “The Boat to Redemption”. His 1992 novels “Rice” and “My Life as Emperor” already evidence the turn toward realism and portentous history often noted in post-[Tiananmen] Massacre works by Yu Hua (author of “To Live”). Su's “Tattoo: Three Novellas”, translated by Josh Stenberg, was published by Merwin Asia in 2012.

“In the academic circle, Su is regarded as one of the contemporary “avant-garde writers” together with Hong Feng, Yu Hua, Ma Yuan, Ge Fei and others. Their works appeared in the 1980s challenging readers with breakthroughs in the form of narration. Critics say these writers have been experimenting with new ideas and some of their works are now being considered classics.” [Source: Liu Jun, China Daily, November 17 2009]

Su is known as a writer who deals sympathetically with women and their feelings. Some of works also contain a fair amount of violence and abuse. When questioned about the violence in his works, Su said he often asks himself the same question. But he argues that what matters is how people deal with the violent legacy of bygone times. “I won't write a novel based on violence. But when I try to capture the bloody smell of iron typical of that time, I shall never avoid it,” Su told the China Daily.

“Raise the Red Lantern” is about the unhappy, rich man’s third wife who is preyed upon by the man’s previous wives. The lantern in the title refers to the lantern that is hung identifying the wife the master wants to sleep with. The 1991 film directed Zhang Yimou, with Gong Li, won the Silver Lion Award at the Venice Film Festival and was nominated for an Academy Award for best foreign film. Spielberg called “Raise the Red Lantern” Zhang’s magnus opus.

Su Tong’s Life

Su Tong was born in 1963, graduated from Beijing Normal University and now is based in Nanjing. Both of Su's parents come from a small island in the Yangtze River and Su was born and grew up by the river in Suzhou, Jiangsu province. It was long a dream of his to write a novel themed on the river.[Source: Liu Jun, China Daily, November 17 2009]

"Su often compares his memories to a box of jewelry, in which lies a bullet. This was inspired by his frightened mother picking up the then 3-year-old Su and taking him to another room when a bullet hit the family's door, close to where Su was sleeping. Su later learned during in the chaotic period leading up to the Cultural Revolution an armed mob had seized a tower across the river and was shooting from it randomly.”This is my first memory, a memory about society and life, a memory that hints at my future in literature,” Su said.” Su became an avid reader at 9, when nephritis confined him to bed. The newspapers pasted on the wall and ceiling were his first teachers, until his elder sister found banned foreign literature from friends and trash tips.” In the 1980s Su studied literature at Beijing Normal University, at a time when writers were seen as heroes.”

“His first novelette was published in 1983, but it wasn't until four years later that his literary career took off. Su wrote about a mulberry garden, based on his early memories, but the draft was turned down by a number of publishers until an editor went to the restroom with a pile of papers to pass the time and spotted his talent. “It was only 5,000 words, but it was a very bright spot. I discovered only then that novel-writing can be relevant to the heart and soul,” Su said.” Su now lives in Nanjing, about 160 kilometers from Shanghai.

Su Tong wins Man Asian Prize for The Boat to Redemption”

At the age of 46 Su Tong won the Man Asian Literary Prize in 2009 for “The Boat of Redemption”, a novel by Su Tong about a disgraced Chinese Communist Party official who is exiled with his son after a false claim is exposed. Set during the Cultural Revolution, “The Boat to Redemption” is about a womanizing Party official who castrates himself after being banished to a river barge with his young son just after the tumultuous Cultural Revolution. Its title, in Chinese, He An, means “river and shore”, representing the worlds of two different types of people — those who live on steady ground are politically reliable; those who live on boats are “exiles” or politically questionable.

“The panel of three judges, including Indian writer Pankaj Mishra and Irish writer Colm Toibin, described Su's novel as a picaresque, political fable as well as “a parable about the journeys we take in our lives, the distance between the boat of our desires and the dry land of our achievement.” On be awarded the prize, Su said, ‘so it's important to me because I'm a writer who is not famous for winning prizes. I'm more famous for not winning prizes.” [Source: James Pomfret, Reuters, November, 16 2009] The Man Asian Literary prize, the regional equivalent of the Man Booker prize. It aims to recognize the region's top writers and give them a platform to reach a broader, international audience. It is awarded annually to a work not yet published into English, with the inaugural prize in 2007 won by China's Jiang Rong for “Wolf Totem.”

Su told the China Daily, “I'm not sure if The Boat to Redemption can help overseas readers know more about China. It's just a novel centering on the fate of people caught in an absurd time...A nation must have the courage to face its own history, whether it's glorious or shameful, beautiful or gray. Misunderstandings often come from hiding and evasion.” The action takes place in a small town in eastern China where former town head, Ku Wenxuan, takes his teenage son into self-imposed “exile”, while his wife and others denounce him and doubt if he is the real descendant of a revolutionary mother.” [Source: Liu Jun, China Daily, November 17 2009]

“The legendary young woman died while smuggling pistols to Communist fighters. Her infant was tossed into the river but a giant carp carried it to an old fisherman. Years later, the fisherman identified Ku in the orphanage, because he had a fish-like birthmark on his bottom. Ironically, almost every man in town has a fish birthmark.” Su's portrayal of the protagonist turns surreal as Ku's quest for redemption becomes extreme, from self-castration to suicide. The story concludes with Ku's son finding a fish at the place where Ku threw himself into the river, carrying his mother's tombstone.” The story is told through the eyes of Ku Wenxuan's son, whose tension with his father drives the story and whose journeys between the boat and shore bring to life an absurd period of Chinese history.”

Writing Boat of Redemption

“I'm very sensitive to the word 'river'. Sometimes I get startled at the word, as if a fire was lit in my heart,” he said in a speech at Peking University in September. Su was concerned that his passion for literature would dim with age and promised himself that he would fulfill his dream of writing about the river before he turned 40. However, it wasn't until 2006 when he took his daughter to visit their old home in Suzhou that he was inspired to start writing. They stood on a bridge littered with rubbish and a fleet of barges sailed by. “I hadn't seen the barges for years. When they went by my mind suddenly lit up. I realized that the story of the river should take place on a boat.” Though he has never lived on a boat, Su is fascinated by boat life, its colorful and earthy expressions. Su depicts sailors as more lenient and uninhibited than bank dwellers.” [Source: Liu Jun, China Daily, November 17 2009]

‘Su Tong must have been born to write, says his friend Wang Gan, who waited seven years to edit his “best work” — The Boat to Redemption. The novel carries all the iconic ‘Su's images and symbols” — river, childhood, death and castration, which appeared in his former works, Wang says in an e-mail interview. The two first met in 1986 and later worked for a literary magazine in the same office.” Wang was hugely relieved and ecstatic when Su called him in 2007 to say that he had begun work on the “real thing”. Half a year later, Wang heard that Su had to throw away some 100,000 words and start from the scratch all over again. Su later told reporters that he was living in a self-imposed confinement for three months in a “quiet and solemn” place in Leipzig, Germany, where the only sound he heard was that of birds' twittering. However, he just couldn't get the right feel.” When Su finally sent him the novel in December 2008, Wang devoured the first two chapters, but then slowed down. “I didn't want to finish the pleasure of reading too quickly. I savored it little by little like a child licking a lollypop. ‘su has surpassed himself again. His novel announces the end of the 'avant-garde literature' era.”

Excerpt from The Boat to Redemption" “Most people live on dry land, in houses. But my father and I live on a barge. Nothing surprising about that, since we are boat people; the terra firma does not belong to us. Everyone knows that the Sunnyside Fleet plies the waters of the Golden Sparrow River all year round, so life for Father and me hardly differs from that of fish: Whether heading upriver or down, most of our time is spent on the water. It's been eleven years. I'm still young and strong, but my father, a rash and careless man, is sinking inexorably into the realm of the aged.” ” [Source: China Daily, November 17 2009]

“Ever since the autumn he has been exhibiting strange symptoms, some age-related, some not. The pupils of his eyes are shrinking and becoming increasingly cloudy — sort of fish-like. He hardly ever sleeps any more; from morning to night he observes life on the shore through fish eyes filled with dejection, occasionally managing to doze a bit in the early morning hours, as he fills the cabin with a faint fishy odor, the earthy smell of a carp, at times especially heavy — even worse, I think, than a dead fish on a line. Sighs of torment escape from his mouth one minute and transparent bubbles merrily appear the next. I've noticed spots on the backs of his hands and along his spine; a few are brown or dark red, but most glisten like silver, and it's these that are beginning to worry me. I can't help thinking that my father will soon grow scales on his body. He has lived an extraordinary life, and I'm afraid he's on the verge of turning into a fish.”

“Anyone who lives on the banks of the Golden Sparrow River is familiar with the martyr Deng Shaoxiang. Hers is a name that appeals to all, refined or common, a stirring musical note in the region's revolutionary history. My father's fate is tied up with the ghost of Deng Shaoxiang. For Ku Wenxuan, my father, was once Deng Shaoxiang's son. Please note that I said 'once'. I had no choice, I had to say it, however inconsequential a word it might seem to you. You see, it is the key to unlocking the story of my father's life.”

Wang Xiaobo

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books: “And who was Wang Xiaobo, the author? He was not part of the state writers’ association and hadn’t published fiction before. But after its publication in Taiwan, The Golden Age was soon published in China and became an immediate success. Wang followed it with a torrent of novellas and essays. He was especially popular with college students, who admired his cynicism, irony, humor — and of course the sex. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, October 26, 2017]

“Just five years later, in 1997, Wang died of a heart attack at the age of forty- four. Few remarked on his passing. Most in China’s literary scene saw him as little more than an untrained writer who had become famous thanks to bawdy, coarse works. Abroad, almost none of his writing had been translated. He seemed destined to be little more than one of the many writers whose works are reduced to fodder for doctoral students researching an era’s zeitgeist.

“In the twenty years since Wang’s death, however, something remarkable has happened. In the West he remains virtually unknown; a single volume of his novellas has been translated into English. But Chinese readers and critics around the world now widely regard Wang as one of the most important modern Chinese authors. He is now included in every major anthology of recent Chinese fiction, and his essays are considered crucial to understanding China’s recent past. The Shanghai- based critic and literature professor Huang Ping told me that Wang now rivals the World War II — era Hong Kong writer Zhang Ailing (better known abroad as Eileen Chang) as the most popular modern Chinese author.

“Wang had no sense of this in his lifetime, according to Li Yinhe, his wife. “There weren’t too many literature reviews of his works in the mainstream, ” she said. “People just began to pay attention to his works and essays. We had no idea of his sales.” Huang has a slightly contrarian explanation of Wang’s popularity. While government critics see him as a libertarian, he can also be read as someone whose irony and sarcasm exonerates middleclass Chinese from responsibility for social problems. Huang said that “instead of explaining how to overcome the issues, [Wang] tells you by his ironic tone that the issues have nothing to do with you.” And yet his books don’t read as if he were a practitioner of what Perry Link calls “daft hilarity” — a use of humor to avoid social criticism. In his fiction, the system and the officials are clearly misguided. His essays are also sharply critical of issues like nationalism. His support for marginalized members of society is now common among Chinese intellectuals in the post- Tiananmen era.

Wang Xiaobo’s Life

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books: ““Wang Xiaobo was born in Beijing in 1952, the fourth of five children; his father, the logician Wang Fangming, was a university professor. That year, the elder Wang had been labeled a class enemy and purged from the Communist Party. The newborn’s name, Xiaobo, or “small wave, ” reflected the family’s hope that their political trouble would be minor. It wasn’t, and people like Wang Fangming were rehabilitated only after Mao died in 1976.

“In his memoirs, Wang’s elder brother, Wang Xiaoping, said their mother was so distraught at her husband’s political problems that she spent her pregnancy weeping. She was unable to breastfeed, and Wang Xiaobo grew up with rickets. He had a slightly bulging skull and a barrel chest, as well as bones so soft that he would entertain his four siblings by yanking his legs behind his head and pulling himself along the floor on his stomach like a crab. His one privilege was sweetened calcium pills, which he ate by the handful while his siblings watched enviously.

“Despite the family’s misfortunes, Wang grew up intellectually privileged. His father had a wide collection of foreign literature in translation. In school, Wang would stare at the wall and ignore his teachers, but at home he devoured works by Shakespeare, Ovid, Boccaccio, and especially Mark Twain. His brother estimated that Xiaobo could read one hundred pages an hour, even of difficult works by Marx, Hegel, or classical Chinese writers.

“When Wang Xiaobo was fourteen, Mao launched the Cultural Revolution, hoping to purge the Party of his enemies and return the revolution to a purer state. After that quickly descended into chaos, Mao ordered young people to go down to the countryside to learn from the peasants. Even though weak, Wang volunteered to go to Yunnan, spurred by romantic fantasies of the border region. He was fifteen when he arrived, and he wrote endlessly while there. He would get up in the middle of the night to scribble with a blue pen on a mirror, cleaning it and then writing again. He dreamed of being a writer and rehearsed his stories over and over again. When he returned to Beijing in 1972 he kept writing but didn’t publish. He worked in a factory for six years, and when universities reopened he got a degree and taught in a high school. All along he stayed silent until one day he couldn’t.

“I met Wang in 1996. At our first meeting, in a hotel near his apartment, he showed up disheveled, wearing a Hawaiian shirt that made him look like a Hong Kong businessman on a weekend fling. He had a big sideways grin and a mop of hair combed over rakishly. He talked garrulously for a couple of hours, and later we went home to meet his wife and play with his computer. He was also an early user of the Internet and spoke up online for disadvantaged groups — then an unusual position but now common among public figures such as the filmmaker Jia Zhangke, the writer Liao Yiwu, and the novelist Yan Lianke.

Wang Xiaobo and Li Yinhe

“In 1980, Wang married, Li Yinhe, a sociologist who later became renowned as China’s leading sex expert.In 1982, the couple moved to the US where Li pursued her doctoral degree at the University of Pittsburgh in sociology, before returning home to join the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), the country’s top research center. [Source: Echo Huang, : Quartz, September 24, 2017]

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books: Li said that they had had a similar upbringing. Both came from educated families, and both had secretly read novels like The Catcher in the Rye. While in the United States in the 1980s, Wang had read Michel Foucault and his ideas about the human body, but she felt he was more influenced by Bertrand Russell and ideas of personal freedom. “The person he liked to cite the most was Russell, the most basic and earliest kind of liberalism, ” she said. “I think he had started reading these books in his childhood.” [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, October 26, 2017]

The two met in 1979 and married the next year. Li was part of a new generation of sociologists trained after the ban on the discipline had been lifted. In the Mao era, sociology had been seen as superfluous because Marxism was supposed to be able to explain all social phenomena. Supported by China’s pioneering sociologist Fei Xiaotong, Li studied at the University of Pittsburgh from 1982 to 1988. Wang accompanied her for the final four years and studiedwith the Chinese- American historian Cho- yun Hsu.

After Li received her Ph.D., the couple returned to China and collaborated on a groundbreaking study, Their World: A Study of the Male Homosexual Community in China. Li eventually took a position at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, and Wang taught history and sociology at Renmin and Peking universities.

Wang’s Writings

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books: “ “The 1989 student movement came and went, ending on June 4 with the Tiananmen massacre. Still, Wang did not publish. “On the night of June 4, we were actually in Xidan [the intersection in Beijing near the worst killings], ” Li said. The couple watched the protesters, hoping they would succeed where their generation had failed. “Wang Xiaobo hid behind a concrete traffic island at a corner of the street to take photos, ” she told me. “We thought at the time that we should just let the young people do it.” [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, October 26, 2017]

“Staying silent became the theme of Wang’s most famous essay, “The Silent Majority.” He describes how during the Mao era people were silenced by the ubiquity of the great leader: his thoughts, his ideas, and his words rained down on people day and night. Later, that left a scar, which for Wang meant that he “could not trust those who belonged to the societies of speech.” The struggle to find a voice became a personal quest and an allegory for the whole nation’s trauma during the Mao era.

“This is what drew Wang to homosexuals in China. Disadvantaged groups were silent groups. They had been deprived of a voice, and society ignored them, sometimes even denying their existence. Then Wang had an epiphany — that all of Chinese society was voiceless: Later, I had another sudden realization: that I belonged to the greatest disadvantaged group in history, the silent majority. These people keep silent for any number of reasons, some because they lack the ability or the opportunity to speak, others because they are hiding something, and still others because they feel, for whatever reason, a certain distaste for the world of speech. I am one of these last groups and, as one of them, I have a duty to speak of what I have seen and heard.

“Only three short works, including The Golden Age and the story “2015” from The Silver Age, are in print in English, published in one volume with the silly title Wang in Love and Bondage. 3 The cover is a disaster, showing a drawing, reminiscent of a 1940s American crime novel, of a man and woman in a cheap hotel room after a tryst. Two other essays are available online, but about 90 percent of his work is untranslated — a strange oversight when publishers are often searching (seemingly desperately, given what sometimes gets translated) to find Chinese voices to explain the country’s rise.

Golden Age

The Golden Age is Wang’s most celebrated work. Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books: “Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books: “In 1992 Wang finished The Golden Age, which he had been working on since returning from Yunnan in 1972. Unsure how to publish it, he sent a copy to Professor Hsu in Pittsburgh. Hsu sent it to United Daily News, a prominent Chinese- language newspaper in Taiwan that sponsored a literary prize. Wang won and entered what he called a “yammering madhouse” — the world of speech.

“Wang was the second son in his family, or er — number two — a name he gave most of his heroes: Wang Er. In The Golden Age, Wang Er is a twentyone- year- old sent to Yunnan, where he meets Chen Qingyang, a twentysix- year- old doctor whose husband has been in prison for a year. Gossips accuse Chen of being “damaged goods” — of having cheated on her husband with Wang — and she asks him to vouch for the fact that they haven’t slept together. Parodying the logical formulas of Wang Xiaobo’s father, Wang Er tells Chen:

We would have to prove two things first before our innocence could be established: 1. Chen Qingyang was a virgin; 2. Castrated at birth, I was unable to have sex. These two things would be hard to prove, so we couldn’t prove our innocence. I preferred to prove our guilt. “Eventually the couple have an affair and retreat to the mountains. They are later rounded up and “struggled against” — put on a stage and forced to reenact their sins. But instead of humiliation, Chen feels only that this is an acting challenge. And when they are forced to confess their sins in writing, both tell the most absurd stories of their sexploits, seeing the punishment as a literary exercise. When freed of this state bullying, the couple make love in their room — a true emotional act that the party couldn’t control.

“The experience makes Wang Er realize that society is nothing more than a series of power relationships. In the village, he notes, locals didn’t just castrate bulls, they also hammered their testicles into a pulp to make sure the bulls got the message. After that, he says, even the feistiest bull was a docile beast of burden. Only much later did I realize that life is a slow process of being hammered. People grow old day after day, their desire disappears little by little, and finally they become like those hammered bulls.

“This message of control is reflected in Wang’s other fictional works. As part of The Trilogy of the Ages, The Golden Age is a novella sandwiched between The Bronze Age, a series of curious stories set in the Tang dynasty (one of which has been recently translated by Eric Abrahamsen as “Mister Lover” ) and The Silver Age, a series of futuristic dystopian stories in which social control is nearly perfected. This makes the Cultural Revolution merely a variation of the suffering that humans have endured in societies throughout the ages. Wang also set down his ideas in two collections of essays published in his lifetime: My Spiritual Homeland and The Silent Majority. Many of the pieces originally appeared in the edgy magazines and newspapers that used to exist in southern China and which over the past decade or so have been hammered into docility.

Ma Jian

Ma Jian is a Chinese writer who was present at the Tiananmen Square protests and now lives in self-imposed exile in London. According to Deutsche Welle: “Ma Jian was born in Qingdao, Shandong Province, East China in 1953. He lived and worked as a writer, photographer and painter in Beijing, then later in Hong Kong, before moving to London in 1999. A political dissident then and an outspoken critic of Communist China ever since, his award-winning literary works of his travels through China and Tibet lent voice to his country's "lost generation."

His most famous book, "Beijing Coma," was published in 2008 and likewise garnered numerous awards. For his book "The Dark Road," published in 2013, which explores China's one-child policy, he traveled extensively through the country's remote interior. “His political activism and demand for free speech have landed him in prison and prompted the ban of his books for the past 30 years in China. They have, however, been translated into numerous languages and have been published in Chinese in Hong Kong and Taiwan. [Source:Deutsche Welle, October 18, 2017]

Mike Ives wrote in the New York Times: Ma was born in the eastern coastal city of Qingdao in 1953, four years after the Chinese Communist revolution of 1949. He initially worked as a manual laborer and a performer in a propaganda theater troupe, and moved to Beijing in the late 1970s to become a painter and photojournalist. “His literary career began when he set off on a three-year journey across China, and later mined his experiences for “Stick Out Your Tongue,” a novella that documents a Chinese drifter’s journey through Tibet. Mr. Ma said the government placed a blanket ban on his work soon after that book was published, and later barred him from visiting the mainland. [Source: Mike Ives, New York Times, December 14, 2018]

In the mid-1980s, divorced from his first wife and abandoned by his girlfriend, Ma Jian left his home with a camera, notebook and copy of Walt Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass” and embarked on a three-year journey around China, getting by on odd jobs and the kindness of friends and strangers. Ma in China. The description of his travels became “Red Dust”, a book described by Pankaj Mishra in The New Yorker as “the most vivid description of the Chinese people freshly liberated from Maoism, picking their way through a transformed moral landscape in which extreme poverty and repression coexist with alluring new possibilities of self invention.” The book ‘seethes with the fraught humanity of a people lurching between credulousness and opportunism, deprivation and semi-bourgeois respectability.”

Beijing Coma and Ma Jian’s Books

“Beijing Coma” by Ma Jian (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2008) is the story of a man who lies in a coma after being shot by stray bullet during the Tiananmen Square massacre. It explores the divisions that existed within the protesters as well as the forces that drove them and features flashbacks to events before the massacre. The narrator describes the changes that occur across China as he lies in a coma. Tash Aw wrote in The Guardian: The brilliance of his 2008 masterpiece, “Beijing Coma,” was already anticipated in “Red Dust”, his atmospheric travel memoir, which recounted the young intellectual's spiritual and political escape from the capital to the west of China in the 1980s. Subsequent fiction such as “The Noodle Maker” and “Stick Out Your” Tongue developed a style that blended internal landscapes with flashes of magic realism and surreal comedy. [Source: Tash Aw, The Guardian, May 2, 2013]

Sam Sacks wrote in the London Review of Books:“In the early 1980s, Ma was one of the ‘questionable youths’ in Beijing’s bohemian underground of independent artists’ collectives and literary journals. His house, he writes in the travel memoir Red Dust (2001), was a meeting place for ‘writers, painters, poets, dissidents and hangers-on’. When he turned thirty, fed up with his job as a photographer for China’s trade unions and suspected by his employers of ‘spiritual pollution’, he travelled to the Tibetan plateau, and when he came back published “Stick Out Your Tongue”, an avant-garde novella comprised of a sequence of bleakly naturalistic sketches. In his Tiananmen Square novel Beijing Coma (2008) he speaks of the reprisals against his book as a turning point: [Source: Sam Sacks, London Review of Books, September 26, 2013]

“A few days after the People’s Literature magazine published “Stick Out Your Tongue”, the Central Propaganda Department denounced it as nihilistic and decadent, and ordered all copies to be destroyed, then proceeded to launch a national campaign against bourgeois liberalism. The hardliners in the party were fighting back. They wanted a more open economy, but not the demands for political and cultural freedoms that it inspired. The brief period of tolerance had come to an end. It felt as though China had been put back ten years. “Stick Out Your Tongue is still very much Ma’s best book. Though his travels began as a naive, Kerouac-like quest for enlightenment, he found that most Tibetans treated him with contempt or indifference. Tibet in the novel is barren and impoverished; its inhabitants sullenly resist Chinese occupation by clinging to ancient practices. The narrator is both aloof and complicit. He alternates between being guiltily appalled by the tales he recounts and luridly voyeuristic whenever women and sex are involved. In a chapter called ‘The Woman and the Blue Sky’, he witnesses the ritual flaying of the corpse of a woman who died during childbirth. With an unnerving mixture of fascination and disgust, he takes part in the ceremony: “The morning sun flooded the burial site with light. The younger brother shooed away the approaching vultures with pieces of Myima’s body. I picked up the axe, grabbed a severed hand, ran the blade down the palm and threw a thumb to the vultures. The younger brother smiled, took the hand from me and placed it on a rock, then pounded the remaining four fingers flat and threw them to the birds.”

“The Noodle Maker, from 1991, is a satire of contemporary Chinese mores that makes a motto of one character’s assertion that ‘the absurd is more real than life itself.’ Broadly in the vein of works by Eastern Bloc dissidents like Josef Skvorecky and Vladimir Voinovich, it tells of a man who’s found success as a professional blood donor and a three-legged dog that sententiously lectures humans on their bestial behaviour, among other absurd figures. Because its arguments tend to be veiled behind caricature, it’s the sort of book that China often allows to be published. (Zhu Wen’s I Love Dollars, just as smutty and caustic a satire, was a runaway hit on the mainland in the 1990s.) Ma in fact submitted The Noodle Maker for publication in China, using a pseudonym. The censors edited it and it was accepted for publication but then the authorities discovered that Ma was the author and had it pulped. China’s censors have refined their measures in recent decades, keeping the rules usefully ambiguous and preferring to wield the soft power of editorial negotiation rather than resort to headline-grabbing arrests or expulsions. Had Ma’s work not first appeared during a particularly reactionary period it’s likely he would have been allowed to publish for a Chinese readership, and his fiction might look much more like that of Zhu Wen and Mo Yan — writers he has criticised for failing to show solidarity with exiled or imprisoned intellectuals.

“Beijing Coma, unlike The Noodle Maker, seems to have been written for an exclusively Western audience. Although it contains a touch of fantasy — it’s told from the point of view of a man who fell into a coma after being shot in the head during the Tiananmen Square protests — the novel is a rather plodding work of documentary realism. The characters speak in history lessons and the story walks step by step from the coalescence of dissident groups in the 1980s to the Tiananmen massacres and finally to the devastating government backlash that followed the uprising (Ma even works in the persecution of the Falun Gong). There was never any chance that the book would make it into print in China outside the black market — even if Ma were not banned, depictions of Tiananmen Square remain strictly off limits — and this is very much the point. Ma organised demonstrations when the book was published outside China and wrote editorials designed to cause maximum embarrassment while the country was on a charm offensive before the 2008 Olympics. He had embraced the role of the protest novelist, in which writing and public dissent serve the same end.

Ma Jian’s The Dark Road

Tash Aw wrote in The Guardian: “The Dark Road” is an angrier, more openly confrontational novel than its predecessors. Set in the river towns and vast waste sites that line the banks of the Yangtze in Guangdong province, it tackles the grim issue of forced abortions and sterilisations with a prolonged and unflinching gaze. The novel's ill-fated heroine, Meili, is born into a simple peasant family and, typically of uneducated girls of her background, marries while still in her teens before giving birth to her one authorised child, a girl, Nannan. But her schoolteacher husband, Kongzi, is a direct descendant of Confucius, whose nickname he shares, and he is desperate to produce a male heir to continue his family's distinguished line. Meili falls pregnant again, with spectacularly bad timing: family planning officers are roaming the countryside implementing a new wave of measures with almost gleeful savagery. The young family is forced to flee the village, eventually joining scattered groups of vagrants along the banks of the Yangtze, drifting from one town to another as itinerant labourers while dodging family planning officers. [Source: Tash Aw, The Guardian, May 2, 2013]

“Much of the wry yet affectionate humour that characterised the earlier novels, even one as obviously political as Beijing Coma, is absent here, replaced by an unrelentingly bleak atmosphere that is rendered all the more stark by Flora Drew's precise yet agile translation. The novel opens with several scenes of shocking violence, in which the women of Meili's village are subjected to horrific cruelty by family planning officers. In one angry confrontation between peasants and officers, a scuffle breaks out and a recently aborted foetus is trampled upon in the ensuing melée. These opening passages could be intended to prepare the reader for what lies ahead, for at virtually every turn, women are brutalised in one way or another as bloody foetuses are carried around in plastic bags or boiled in Cantonese restaurants to make male-tonic soups.”

“It's not easy to endure the relentless stream of misfortune and suffering that afflicts Meili and her family wherever they go. The desperate world of migrant workers, many of whom are also on the run from family planning officers, is filled with tragic encounters that cumulatively read like a catalogue of every scandal to afflict modern-day China. Toxic industrial waste that has turned the famous Yangtze as "red as Oolong tea"; chemically produced fake milk powder; watermelons injected with growth hormones; mouldy rice milled with wax and resold as new; corrupt party officials; the ill treatment of the mentally ill — these horrors fill the pages of the novel, snuffing out any traces of optimism, such as Kongzi's furtive efforts to grow seasonal herbs and Meili's fleeting yet tender encounter with a man in search of his drowned mother's corpse. It is as though Ma is forcing the reader to experience the same harshness faced by migrant workers; but at the same time, Meili's unfading innocence and faith in humanity make us long for a conventional happy ending, even if we suspect there isn't going to be one.

“The novel is at its provocative best towards the end, when Meili and her family reach Heaven Township in the far south of the country, famed for its lax approach to family planning as well as for its concentration of factories that feed China's economic boom. All of Ma's skill and playfulness are on display as the novel builds to a climax in which Meili is forced to question her very right to exist in this fragile, ever-changing new world.

Ma Jian’s Chinese Dream

“China Dream,” Ma’s satirical novel about President Xi Jinping’s domestic propaganda campaign by the same name, was published month in English by Counterpoint in November 2018 and became available in the United States in May 2019 and showed, according to Ma, how the dystopian future that George Orwell’s fiction once warned about had become a reality in the Chinese mainland under Mr. Xi’s leadership..Mike Ives wrote in the New York Times: ““China Dream” is a sharper political allegory than Mr. Ma’s earlier novels. It crackles with bruising satire of Chinese officialdom, and an acerbic wit that vaguely recalls Gary Shteyngart’s sendup of Russian oligarchs in “Absurdistan,” or even Nikolai Gogol’s portraits of Russia’s provincial aristocrats in “Dead Souls.” Maura Cunningham, a historian of modern China based in Ann Arbor, Michigan told the New York Times: “In ‘China Dream,’ Ma blends fact and fiction to explain how Xi Jinping and the party are enacting violence against, and even attempting to eradicate, the collective memory of China’s recent history.” [Source: Mike Ives, New York Times, December 14, 2018]

““China Dream” may be the purest distillation yet of Mr. Ma’s talent for probing the country’s darkest corners and exposing what he regards as the Communist Party’s moral failings. The slender novel charts the mental breakdown of Ma Daode, a farcically corrupt provincial official who, when he is not busy arranging trysts with mistresses, is devising a “China Dream Device” that would help Mr. Xi’s increasingly authoritarian government erase civilians’ memories of the country’s postrevolutionary past. But the project fails, mostly because the repression and censorship that Ma Daode carries out as a ham-handed functionary constantly triggers flashbacks to violence he suffered through — and participated in — as a young man during the Cultural Revolution.

““Why was I not buried along with my comrades, all those years ago?” Ma Daode asks himself at one point, after passing near the graves of victims of Mao-era violence. Even a visit to a brothel called the “Red Guard Nightclub” does not help him clear his mind. The prostitutes there are dressed in military uniforms, and his mind drifts from lust to a painful vision: the anguished face of his father, who committed suicide after suffering beatings at the hands of Mao-era officials. But even if “China Dream” paints a withering portrait of China’s official class, Ma Daode’s pangs of conscience also suggest that even people who participate in a deeply corrupt and repressive system are capable of redemption. Mr. Ma said he had modeled the character on Winston Smith, Orwell’s protagonist in “1984,” who struggles to reclaim a sense of history even as an authoritarian government attempts to create a new reality.

Image Sources: Amazon, University of Washington, Ohio State University, Amazon.com, Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html , Wikipedia, Achievement.org, Landberger posters

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021