TRANSPORTATION IN TIBET

Up until 2006 Tibet had no railroad. People mostly get around with horses, motorcycles, trucks, minibuses, SUVs, jeeps, and tractor-pulled wagons. Horses have been the traditional animal of choice of herders. Helicopters don't work so well in high elevations. Caravans have been replaced by trucks. See Caravans Below

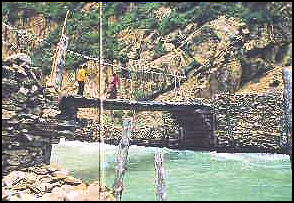

According to the Chinese government: Communications were poor in the old days, with yaks and mules as the chief means of transport. Riding horses were reserved for the manorial lords, who decorated the saddles according to their ranks and positions. Cattle hide rafts, wooden boats and canoes hewed out of logs were used in water transportation. Suspension, cable and simple wooden bridges were seen occasionally. [Source: China.org china.org |]

Tibet Airlines is a regional airline based in Lhasa. It has a fleet of 39 planes, including 28 A319s, according to Airfleets.net. In May 2022. China has built the world’s highest airports in Tibet. One is located at 4,200 meters in northern Ngaro Prefecture. It was the fourth airport in Tibet. A third airport began operating in Nyungchi in southeast Tibet in September 2006.

See Separate Articles: GOVERNMENT OF TIBET: CHINESE CONTROL, TRADITIONAL RULE AND THE CTA factsanddetails.com; CHINESE GOVERNMENT POLICY AND DEVELOPMENT IN TIBET factsanddetails.com TIBETAN TRAINS: ROUTES, CONSTRUCTION AND IMPACT factsanddetails.com; TOURISM IN TIBET factsanddetails.com; NATURAL RESOURCES, MINING AND OPPOSITION TO IT IN TIBET factsanddetails.com;; PLACES IN TIBET factsanddetails.com; CHINA TRANSPORTATION Factsanddetails.com/China; Wikipedia articles Wikipedia

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Tibet Transportation” (1991) by Editors: Zhang Ying etc. Amazon.com; “Lonely Planet Tibet 10 by Stephen Lioy , Megan Eaves , et al. (2019) Amazon.com; “Tibet: A Travel Survival Kit (Lonely Planet Tibet) by Robert Strauss (1992) Amazon.com; “Riding the Iron Rooster: By Train Through China” by Paul Theroux Amazon.com; “Tibet: A traveler's guide book”by White L Mill Amazon.com; “China's Great Train: Beijing's Drive West and the Campaign to Remake Tibet” by Abrahm Lustgarten Amazon.com; Amazon.com; “Taking the Train to Tibet” by Chen Yang | Amazon.com; “Tea Horse Road: China's Ancient Trade Road to Tibet” by Selena Ahmed and Michael Freeman Amazon.com; “The Ancient Tea Horse Road”by Jeff Fuchs Amazon.com; “The Ancient Tea Horse Road: Travels With the Last of the Himalayan Muleteers” by Jeff Fuchs Amazon.com; “Himalaya” (2001 DVD) Amazon.com;

Transportation Infrastructure in Tibet

Infrastructure projects like maintaining trails and building log bridges have traditionally been done on a community basis. When a bridge is built over a mountain stream, for example, one family may bring in logs from a far away forest while other villagers donate their labor to build the bridge. In March 2007, Beijing announced it would spend $13 billion over three years to develop 180 projects — including extending the new railroad, building new airports, and developing water, electricity and telephone infrastructure — in Tibet in an apparent move by Beijing to improve its image in the region.

Many of the things built by the Chinese in Tibet — roads, settlements, telegraph lines, barracks — are things necessary to keep the supply lines going for an occupying force. The first Chinese arrivals in an area are often surveyors and engineers, followed by soldiers. Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker in 2010: “We passed frequent reminders that China is determined to pull this region closer to the rest of the country. We saw a crew of hundreds of workers erecting pylons that will carry a new highway, and another team sinking a tunnel into a mountain.”

According to the Chinese government: “There was no highway in Tibet before 1950. Since the People's Liberation Army marched into Tibet, several major trunk roads were built, including the Qinghai-Tibet highway (1954), the Sichuan-Tibet highway (1954), the Yunnan-Tibet highway (1976) and the Xinjiang-Tibet highway (1957) which linked up the Tibetan areas. A network of motor roads fanning out from Lhasa has been formed, extending to almost all counties. In 1984, the total length of roads open to traffic in Tibet reached 21,500 kilometers. The people's air force made the first successful flight from Beijing to Lhasa in 1956 and since then regular air services have linked Lhasa with Xining, Chengdu, Lanzhou and Xi'an. Roads also connect Tibet with the Kingdom of Nepal. [Source: China.org china.org |]

Motorcycles in Tibet

In recent years motorcycles have become popular and have begun replacing horses as the vehicle of choice among nomads on the plateau. One nomad who had just bought a ASIAHERO 150-7 motorcycle told the New York Times "I use to ride a horse. A motorcycle is faster.” Another said, “You’re only a real nomad if you ride a horse.” Then, glancing at his motorcycle, he said, “But this is my horse.”

A new motorcycle goes for around $600, and used one can be had for as little as $50, considerably less than a horse. On Tibetan roads you often see leather-clad, goggled, motorcycle riders.

With a motorcycle journeys that use to take several days now can be done in a few hours. Herding chores that used to take three or four people can be done with a rider and a single motorcycle. Good shock absorbers are a must for riding across grassland areas. Some motorcycle owners decorate their bikes with photographs of the Dalai Lama and ornate Tibetan rugs and ride with felt cowboy hats. New bike are blessed by local lamas. The biggest drawback with motorcycles is the high cost of gasoline.

Roads and Highways in Tibet

Poor roads are one of the biggest obstacle to development in Tibet. Cliffs, poor drainage, high elevation, temperature extremes are all obstacles that make road building difficult and slow. When roads are built that are often blocked by landslides, mudslides and washouts from flash floods and break up from expansion and contraction caused by extreme hot and cold temperatures.

Poor roads are one of the biggest obstacle to development in Tibet. Cliffs, poor drainage, high elevation, temperature extremes are all obstacles that make road building difficult and slow. When roads are built that are often blocked by landslides, mudslides and washouts from flash floods and break up from expansion and contraction caused by extreme hot and cold temperatures.

A road network with Lhasa as the center and the Qinghai-Tibet highway, the Sichuan-Tibet highway, the Xinjiang-Tibet highway, the Yunnan-Tibet highway and the China-Nepal highway as the framework has come into being. Among them, there are 15 main highways, and 315 feeder highways. The highways extending in all directions connect all the counties and 77 percent of the townships of Tibet. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, kepu.net.cn, 2005]

The Chinese government built internal highways and links to the Chinese provinces. But some of their plans go too far. There have been rumors that the Chinese are planning to build a road around Mount Kailash — one of the most spiritual mountains in the Himalayas, sacred to Hindus, Buddhists, Jains and Bonpos. “It would be a horrible thing to happen,” says Chris Berry of King’s College, London,“Sacrilegious in the most horrible way.” [Source: Hazel Plush, The Telegraph, December 14, 2016]

Sichuan-Tibet Highway See EASTERN TIBET factsanddetails.com Xinjiang-Tibet Highway see WESTERN TIBET factsanddetails.com See Places of Tibet factsanddetails.com

Road Travel in Tibet

Some town roads are ankle deep in mud and animal shit. In many places where there are no bridges people and goods are moved across rivers on ropes or wires rigged with pulleys. In some cases men travel with their fully-loaded horses on the rope bridges, moving along by pulling themselves hand over hand.The Chinese have devoted a lot of money and effort into building and improving roads in Tibet. You will meet many Tibetans who complain about the Chinese but you won’t find that many who complain about the Chinese roads.

Before the completion of the new railway in 2006 it was no easy task getting supplies to Tibet. The twisting 1,400-mile road that links Sichuan with Tibet, for example, takes two weeks to traverse by truck. It goes up and down through valleys and over mountain passes. For every six trucks that make the trip an additional truck must come along to supply fuel. Heavy machinery bound for Tibet had to be disassembled, loaded onto trucks and reassembled in Tibet.

Tourists traveling from Golmund to Lhasa have endured car accidents, broken axles, cars that break down in the middle of blizzards and 30 hours of standing up on a bus. Bridges often get washed out. When that happens truck are forced to drive to the river bank, drive across the riverbed and struggle up the riverbank on the other side.

In January 2005, 54 Tibetan Buddhist pilgrims were killed and 41 were injured when the truck carrying them overturned on a mountain road in the Qinghai region north of Tibet. The pilgrims were mostly from Ganzi and Aba, ethnic Tibetan regions of Sichuan. They were returning from a pilgrimage to Lhasa.

Construction of Tibet’s Roads

After the Chinese grabbed control of Tibet the Tibet-Qinghai highway was built from Golmud to Lhasa. The People's Liberation Army worked incredibly hard to build the Tibet-Qinghai and Tibet-Sichuan highways. Originally animal tracks and pathways, they were completed in 1954.

Construction of the Sichuan-Tibet road started immediately after China claimed Tibet in 1950-51. According to Xinhua: Ma Chengshan, then chief of staff in the army, recalled that the task was "urgent." Chairman Mao Zedong told them not to disturb the local people, so the soldiers had to dig edible wild herbs and catch mice to eat. "The snow was so deep that it sometimes reached the waist of the soldiers," Ma said. "We worked from dawn to dusk, our clothes were always wet." Due to the bad climate and geographic disasters, many soldiers died along the way. "Under every meter of the road there lies a soldier," Ma said. The 2,413-km road, together with another linking Qinghai and Tibet, opened in 1954. [Source: Xinhua, July 18, 2011]

Today, "all townships and more than 80 percent of the administrative villages in Tibet have gained access to highways, which now total 58,200 km," according to the white paper from the Information office. China's last isolated county was connected to the country's highway network with the completion and operation of the Galungla tunnel on the Metok Highway last December 2010. The road was completed in 2012. Improvement of road conditions has gone hand in hand with a rise in the number of automobiles. As of September 2010, Tibet had a total of 216,478 automobiles. Its per capita ownership ranked third in China.

The comprehensive road network is changing people's lives. Cuddling her baby in her arms, 23-year-old Tsering Lhamo said she's thankful to a new road, which opened in her village Naiyu in Mainling County, Nyingchi last year. "In the past, there was only one rugged road in our village," she said. The cobbled road was a cattle track. Traveling on it normally took villagers a day to reach the county seat. Many pregnant women delivered on the way to hospital, while some others miscarried. More chose to give birth to their babies at home, but without proper sanitation, it could be dangerous. "My elder sister delivered at home, but the baby died," Tsering Lhamo recalled bitterly. It only took Tsering Lhamo's husband two hours to drive her to the county hospital on the newly built road

Tibet’s First Expressway

When he was vice president, Xi Jinping cut the ribbons at the opening ceremony for the first expressway in Tibet in July 2011. Xinhua reported: The 37.8-km long, four-lane road links Lhasa's city center with Gonggar Airport in the neighboring Shannan Prefecture. The toll-free expressway will halve the travel time from downtown Lhasa to the airport to 30 minutes. "It will make the trip more convenient," said Yonten, 31, who has been working as driver for a company in Lhasa for three years.[Source: Xinhua, July 18, 2011]

In summer, when the Lhasa River swells, the old road from Lhasa to the airport could become flooded, Yonten said. According to the driver, the old road, No. 318 National Highway, is narrow and jammed with traffic year round. "I once waited half an hour and almost missed my flight," he said. "The new expressway will ease traffic pressure on a section of No. 318 National Highway," said Zhao Shijun, head of the transportation department of Tibet.

Construction of the expressway began in April, 2009 and was completed in early July, 11 months ahead of schedule. The $246 million expressway has a speed limit of 120 kilometers per hour, and its roadside lighting is powered by solar energy.

China-Tibet Tea Horse Road

Highway from Sichuan to Tibet Mark Jenkins wrote in National Geographic, “Deep in the mountains of western Sichuan I'm hacking through a bamboo jungle, trying to find a legendary trail. Just 60 years ago, when much of Asia still moved by foot or hoof, the Tea Horse Road was a thoroughfare of commerce, the main link between China and Tibet. But my search could be in vain. A few days earlier I met a man who used to carry backbreaking loads of tea along the path; he warned me that time, weather, and invasive plants may have wiped out the Tea Horse Road.”[Source: Mark Jenkins, National Geographic, May 2010]

“Then, with one wide sweep of my ax, the bamboo falls. Before me is a four-foot-wide cobblestone trail curving up through the forest, slick with green moss, almost overgrown. Some of the stones are pitted with water-filled divots, left by the metal-spiked crutches used by hundreds of thousands of porters who trod this trail for a millennium. The vestigial cobblestone path lasts only 50 feet, climbs a set of broken stairs, then once again disappears, swept away by years of monsoonal deluges. I carry on, entering a narrow passage where the sidewalls are so steep and slippery I have to hang on to trees to keep from falling into the bouldery creek far below. I'm hoping, at some point, to cross over Maan Shan, a high pass between Yaan and Kangding.”

“That night I camp high above the creek, but the wood is too wet to make a fire. Rain pounds the tent. In the morning I probe ahead another 500 yards before an impenetrable wall of jungle stops me, for good. I'm forced to admit that here at least the Tea Horse Road has vanished. In fact, most of the original Tea Horse Road is gone. Recklessly rushing to modernity, China has been paving over its past as fast as possible. Before the trail is bulldozed or obliterated, I've come to explore what's left of this once famous but now all-but-forgotten route.”

“The ancient passageway once stretched almost 1,400 miles across the chest of Cathay, from Yaan, in the tea-growing region of Sichuan Province, to Lhasa, the almost 12,000-foot-high capital of Tibet. One of the highest, harshest trails in Asia, it marched up out of China's verdant valleys, traversed the wind-stripped, snow-scoured Tibetan Plateau, forded the freezing Yangtze, Mekong, and Salween Rivers, sliced into the mysterious Nyainqentanglha Mountains, ascended four deadly 17,000-foot passes, and finally dropped into the holy Tibetan city.” ‘snowstorms often buried the western part of the trail, and torrential rains ravaged the eastern portion. Bandits were a constant threat. Yet the trail was heavily used for centuries, even though the cultures at either end at times despised each other (and still do). The desire to trade was why the trail existed, not the romantic swapping of ideas and ethics, culture and creativity associated with the legendary Silk Road to the north. China had something Tibet wanted: tea. Tibet had something China desperately needed: horses.

Working on the Tea Horse Road

.jpg)

Sail assisted wheelbarrowsToday the trail lives on in the memories of men like Luo Yong Fu, a watery-eyed 92-year-old whom I met in the village of Changheba, a ten-day walk for a tea porter west of Yaan,” Mark Jenkins wrote in National Geographic. “When I first arrived in Sichuan, I was told no tea porters were still alive. But as I walked the last remnants of the Chamagudao, the Chinese name for the ancient trade route, I met not only Luo, but also five others, all eager to share their stories. Stooped but still surprisingly strong, Luo Yong Fu wore a black beret and a blue Mao jacket with a pipe in the pocket. He had worked on the Tea Horse Road as a porter, carrying tea to Tibet from 1935 to 1949. Luo's load of tea always weighed 135 pounds or more. At the time, he weighed less than 113 pounds.” [Source: Mark Jenkins, National Geographic, May 2010]

"Difficulties were so great and the hardship so enormous," Luo said. "It was a terrible job." Luo had crossed back and forth over Maan Shan, the point I had hoped to reach. In winter the snow was three feet deep and six-foot icicles hung from the rocks. He said the last time someone had crossed the pass was in 1966, so he doubted whether I would be able to do it.” “But I did get a glimmer of what it must have been like to travel the road. In Xinkaitian, the first stop on the tea porters' 20-day trek from Yaan to Kangding, clean-shaven Gan Shao Yu, 87, and bristle-faced Li Wen Liang, 78, insisted on acting out their lives as porters. Backs bent beneath immense, imaginary loads of brick tea, veiny hands on T-shaped crutches, heads down and eyes on their splayed feet, the two old men showed me how they wobbled single file along a wet stretch of cobblestone. After seven steps Gan stopped and stamped his crutch three times, following tradition. Both men circled their crutches around to their backs to rest their wood-frame packs atop the crutch. Wiping sweat from their brows with phantom bamboo whisks, they croaked out the tea porter song: ‘seven steps up, you have to rest. / Eight steps down, you have to rest./ Eleven steps flat, you have to rest. / You are stupid, if you don't rest.”

“Tea porters, both men and women, regularly carried loads weighing 150 to 200 pounds; the strongest men could carry 300. The more you carried, the more you were paid: Every pound of tea was worth a pound of rice when you got back home. Wearing rags and straw sandals, porters used crude iron crampons for the snowy passes. Their only food was a satchel of corn bread and an occasional bowl of bean curd.” "Of course some of us died on the way," Gan said solemnly, his eyelids half shut. "If you got caught in a snowstorm, you died. If you fell off the trail, you died." Tea portering ended soon after Mao took over the country in 1949 and a highway was built. Redistributing land from the wealthy to the poor, Mao released the tea porters from servitude. "It was the happiest day of my life," Luo said. After he received his parcel of land, he began to grow his own rice and "that sad period passed away."

History of the Tea and Horse Trade Between China and Tibet

Tea carriers in 1908 “Tea was first brought to Tibet, legend has it, when Tang dynasty Princess Wen Cheng married Tibetan King Songtsen Gampo in A.D. 641,” Mark Jenkins wrote in National Geographic. “Tibetan royalty and nomads alike took to tea for good reasons. It was a hot beverage in a cold climate where the only other options were snowmelt, yak or goat milk, barley milk, or chang (barley beer). A cup of yak butter tea — with its distinctive salty, slightly oily, sharp taste — provided a mini-meal for herders warming themselves over yak dung fires in a windswept hinterland.” [Source: Mark Jenkins, National Geographic, May 2010]

“The tea that traveled to Tibet along the Tea Horse Road was the crudest form of the beverage. Tea is made from Camellia sinensis, a subtropical evergreen shrub. But while green tea is made from unoxidized buds and leaves, brick tea bound for Tibet, to this day, is made from the plant's large tough leaves, twigs, and stems. It is the most bitter and least smooth of all teas. After several cycles of steaming and drying, the tea is mixed with gluey rice water, pressed into molds, and dried. Bricks of black tea weigh from one to six pounds and are still sold throughout modern Tibet.”

By the 11th century, brick tea had become the coin of the realm. The Song dynasty used it to buy sturdy steeds from Tibet to take into battle against fierce nomadic tribes from the north, antecedents of Genghis Khan's hordes. It became the prime trading commodity between China and Tibet. For 130 pounds of brick tea, the Chinese would get a single horse. That was the rate set by the Sichuan Tea and Horse Agency, established in 1074. Porters carried tea from factories and plantations around Yaan up to Kangding, elevation 8,400 feet. There tea was sewn into waterproof yak-skin cases and loaded onto mule and yak trains for a three-month journey to Lhasa.”

“By the 13th century China was trading millions of pounds of tea for some 25,000 horses a year. But even all the king's horses couldn't save the Song dynasty, which fell to Genghis's grandson, Kublai Khan, in 1279. Nonetheless, bartering tea for horses continued through the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) and into the middle of the Qing dynasty (1645-1912). When China's need for horses began to wane in the 18th century, tea was traded for other goods: hides from the high plains, wool, gold, and silver, and, most important, traditional Chinese medicinals that thrived only in Tibet. These are the commodities that the last of the tea porters, like Luo, Gan, and Li, carried back from Kangding after dropping off their loads of brick tea.”

“Just as China's imperial government used to regulate the tea trade in Sichuan, so monasteries influenced the trade in theocratic Tibet. The Tea Horse Road, known to Tibetans as the Gyalam, connected the important monasteries. Over the centuries, power struggles in Tibet and China changed the Gyalam's route. There were three main trunk lines: one from the south in Yunnan, home of Puer tea; one from the north; and one from the east cutting through the middle of Tibet. Because it was the shortest, this center route handled most of the tea.”

Following the Tea Horse Road

“Today the northern route, Highway 317, is blacktop,” Mark Jenkins wrote in National Geographic. “Near Lhasa it parallels the Qinghai-Tibet railway, highest in the world. The southern route, Highway 318, is also oiled. These highways are major arteries of commerce, clogged with trucks carrying every imaginable commodity from tea to school tablets, solar panels to plastic plates, computers to cell phones. Almost all of it goes one way — west to Tibet, to meet the needs of a ballooning Chinese population.” [Source: Mark Jenkins, National Geographic, May 2010]

“The western half of the middle route has never been paved. This is the segment that winds through Tibet's remote Nyainqentanglha Mountains, an area so rugged and inhospitable it was simply abandoned decades ago and the entire area closed to travelers. I'd seen what was left of the original trail in China. To do the same in Tibet, I'd have to find a way into these forbidden mountains. I called my wife, Sue Ibarra, who is an experienced mountaineer, and asked her to meet me in Lhasa in August.”

We begin our journey at the Drepung monastery, which lies at the western end of the Tea Horse Road — less than a day's horse ride from Lhasa. Built in 1416, it has a cavernous tea kitchen, or gyakhang. Seven iron cauldrons from six to ten feet in diameter are imbedded in a gargantuan, wood-fired, stone hearth. Standing above a cauldron, Phuntsok Drakpa cleaves off tome-size slabs of yak butter into the steaming tea.” "There were once 7,700 monks here who drank tea twice a day," he says. "More than a hundred monks worked in this tea kitchen." Swathed in a sleeveless maroon robe, Drakpa has been the tea master in the monastery for 14 years. "To Tibetan monks," he says, "tea is life."

Today only 400 monks reside in the monastery, and only two small cauldrons are in use. "For one little cauldron, 25 bricks of tea, 70 kilos of yak butter, 3 kilos of salt," says Drakpa, stirring this recipe for 200 with a wooden spoon tall as a human. "For the biggest cauldron, we used seven times that much."

Journey on the Tea Horse Road to a Nomad Camp

In Nagqu Jenkins visited a horse festival. “Today Nagqu sits on modern Highway 317, the northern branch of the Tea Horse Road,” Mark Jenkins wrote in National Geographic. “All signs of the former trade route have vanished, but just a day's drive southeast, temptingly close, are the Nyainqentanglha Mountains, where the original trail once passed. I am captivated by the possibility that back in the deep valleys Tibetans might still ride their indefatigable horses along the original trail. Perhaps, hidden in the vast hinterland, there is even still trade along the road. Then again, maybe the trail has vanished as it did in Sichuan, wiped out by howling wind and tumbling snow.” [Source: Mark Jenkins, National Geographic, May 2010]

“One rainy black morning halfway through the festival, while the police are looking the other way, Sue and I slip off in a Land Cruiser to find out what has happened to Tibet's Tea Horse Road. We race all day on dirt roads, grinding over passes, almost rolling on steep slopes. We don't stop at checkpoints, and we creep right past village police stations. By nightfall we reach Lharigo, a village between two enormous passes that once served as a sanctuary along the Gyalam. Surreptitiously, we go door-to-door looking for horses to take us up to 17,756-foot Nubgang Pass. There are none to be found, and we're directed to a saloon on the edge of town. Inside, Tibetan cowboys are drinking beer, shooting pool, and placing bets on a dice game called sho. They laugh when we ask for horses. No one rides horses anymore.”

“One rainy black morning halfway through the festival, while the police are looking the other way, Sue and I slip off in a Land Cruiser to find out what has happened to Tibet's Tea Horse Road. We race all day on dirt roads, grinding over passes, almost rolling on steep slopes. We don't stop at checkpoints, and we creep right past village police stations. By nightfall we reach Lharigo, a village between two enormous passes that once served as a sanctuary along the Gyalam. Surreptitiously, we go door-to-door looking for horses to take us up to 17,756-foot Nubgang Pass. There are none to be found, and we're directed to a saloon on the edge of town. Inside, Tibetan cowboys are drinking beer, shooting pool, and placing bets on a dice game called sho. They laugh when we ask for horses. No one rides horses anymore.”

“Outside the saloon, instead of steeds of muscle standing in the mud, there are steeds of steel: tough little Chinese motorcycles decorated like their bone-and-blood predecessors — red-and-blue Tibetan wool rugs cover the saddles, tassels dangle from the handlebars. For a price, two cowboys offer to take us to the base of the pass; from there we must walk.”

“We set off in the dark the next morning, backpacks strapped to the bikes like saddlebags. The cowboys are as adept on motorbikes as their ancestors were on horseback. We bounce through black bogs where the mud is two feet deep, splash through blue braided streams where our mufflers burble in the water. Up the valley we pass the black tents of Tibetan nomads. Parked in front of many of the yak hair tents are big Chinese trucks or Land Cruisers. Where did nomads get the money to buy such vehicles? Certainly not from the traditional yak meat-and-butter economy.”

“It takes five hours to cover the 18 miles to Tsachuka, a nomad camp at the base of the Nubgang Pass. The ride thoroughly jars our spines. The cowboys build a small sagebrush campfire and, after a lunch of yak jerky and yak butter tea, Sue and I set off on foot for the legendary pass. To our delight, the ancient path is quite visible, like a rocky trail in the Alps, winding up meadows speckled with black, long-horned yaks. After two hours of hard uphill hiking, we pass two shimmering sapphire tarns. Beyond these lakes, all green disappears and everything turns to stone and sky. Mule trains of tea stopped crossing this pass over a half century ago, but the trail had been maintained for a thousand years, boulders moved and stone steps built, and it's all still here. Sue and I zigzag through the talus, along the walled path, right up to the pass.” “The saddle-shaped Nubgang Pass has clearly been abandoned. The few prayer flags still flapping are worn thin, the bones atop the cairns bleached white. There is a silence that only absence can create...In my imagination I see a mule train of a hundred animals plodding up toward us, dust swirling around their hooves, loads of tea rocking side to side, the cowboys alert for bandits waiting in ambush on the Nubgang Pass. Our motocowboys are waiting for us the next morning when we return from the pass. We saddle up and begin the long ride out, bumping and bashing down glacial valleys.”

Tibetan Caravans

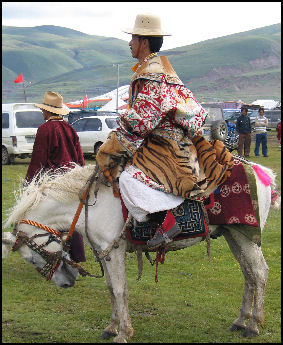

Tibetan horseman

Caravans crossing the Himalayas still operate between Tibet and Nepal. Nomads, who live at an altitude above which the grain can not grow, gather salt from beds near Tibetan lakes and trade it for barley, buckwheat, rice and maize with caravans that come from up Nepal and Bhutan. Sometimes things like kerosene lamps, Indian cloth and even bicycles are carried in. [Source: Eric Valli and Diane Summers, National Geographic, December 1993, ☺]

Salt caravans with 150 or so yaks have been operating in Tibet for more than 2,000 years. Caravans between Tibet and the Dolpo area of Nepal have been traveling the same route for more than a thousand years. Within Tibet, caravans have been replaced by trucks. The trucks able to reach the salt-producing lakes but still can not take the salt over high mountain passes into Nepal. Thus there is still a need for the caravans.

Salt is used in the preparation of meals and, more importantly, to feed it animals. In some places it is still used as currency or as a commodity to barter for rice or other commodities with lowland people. For people in Nepal, salt from Tibet is considerably cheaper than salt from India.

Caravans are usually organized in the fall so herders and grain growers can get supplies to last them through the winter. Caravaneers in the Dolpo only raise enough grain to meet about half of their needs. With the money made by trading salt they buy additional grain and things like tea, sugar plastic bowls, and tools. Members of the caravan usually deal with same trading partners year after year. Trust is important. Salt and grain are measured out in sacks or wooden khekours. Typically two measures of salt are traded for five measures of grain.

Tibetan Sheep and Yak Caravan

The salt caravans traveling between the Dolpo region of Nepal and the Chang Tang region of Tibet are made up of sheep who wear 30 pounds saddlebags. The sheep wear the bags even when they are sleeping so the nomads don't have to waste time taking them off and putting them on. At night the caravan members sleep in make-shift yurt-like tents made from canvas stretched over a circle constructed of piles of sacks and other equipment. Meals are prepared over fires made inside the tents.

Road travel

The salt comes from the bottom of shallow lakes in the Chang Tang region. It is raked it in heaps which dry out in the sun and then sewn into huge sacks that are loaded on the back of the animals. To keep from getting frostbite the caravaneers wrap their feet in woolen rags. And to prevent snow blindness men wrap their long braids over their eyes and women smear black roots under their eyes.☺♠

Twice-a-year yak caravans ply a route between the Tsangpo river valley area of Tibet and the Tsangpo upland valley in Nepal. The caravans move with one man following behind four yaks. Each yak carries about 150 pounds placed in two sacks, one hanging on each side of a wooden saddle placed on the yak’s back. The journey takes about 10 days. Yaks from Tibet carry salt, animal fat and wool, which is exchanged for grain and sometimes lowland goods like rice, pears and sugar. The governments of China and Nepal tolerate the caravans because the people involved depend on the caravans for their survival.

Tibetan Caravan Rituals

Before a caravan begins, a consultation with the gods using a lama or shaman as an intermediary takes place and yak butter is placed on the brow and horn tips of each yak with the understanding that gods like butter and will protect the animals to show their gratitude. Wives also dab butter on the heads of their husbands. These rituals are believed to offer protection from rock slides, blizzards, falls from cliffs and dangerously cold and wet weather.

When a sheep caravan is ready to embark on a journey to the lowlands, the event is heralded with handfuls of barley thrown into the air and chants from lamas and honks from conch shell horns. The leader of the caravan thrusts his arm into the chest of a slaughtered sheep and draws out a cup of blood, which he drinks slowly. This is done to protect him from malaria and dysentery.

Instead of saying grace before a meal some everyone dips their forth finger into their tea and flick the droplets in the four directions. To forecast, the weather salt is thrown into the air and then tossed onto a fire. If it crackles it means a storm is far away if it stays silent it means a storm in near.

The caravaneers sing and chant during their journey in a "salt language" known only to themselves and the Buddhist deities that are important to them. If an accident occurs, the caravan will not continue forward until the spiritual cause of the accident is found and something is done to atone for it, even if it means falling behind schedule and risking getting caught in a storm. To appease spirts, a lama or shaman may recommend making 108 little cakes as offerings or making effigies of people who have been injured and who are ill. The effigies are throw down a gorge to fool the spirts that they are the real people.

Travel With a Tibetan Caravan

Caravan camp

The lead yak in a yak and sheep caravan has a red tassel hanging from it ear and prayer flag tied to its coat. Other yaks are adorned with pom poms and bells. Slow beasts are urged on with rocks slung from a slingshot and calmed with clicking noises.

On sheep caravans the saddlebags on the animals have to constantly be adjusted. On the narrow trails an off-balance, lopsided bag can send a sheep hurtling over the side of a cliff. During the night one of the caravan members stays up all night to make sure the sheep don't get picked off by leopards and jackals.☺

When its time to go to sleep men, women and children disrobe and sleep together under the same blankets and on top of the same goatskin mattress. The mainstay of a caravaners diet is tea flavored with rancid butter and salt. "Tea is the horse of the traveler" a saying goes. "It gives us energy and keeps us going."☺

When an unexpected snow storm hits, small yaks are forced to return and large yaks are relieved of their bags so they can break a trail for the rest of the caravan. Describing a snowbound caravan heading Nepal to Tibet, Christine de Cherriey wrote in Smithsonian, "It is an arduous hike. Sometimes Chusang [the caravan leader] has to walk in front of the yaks in snow up to his thighs. The men shield their eyes from the sun; those who do not have glasses cover their eyes with their braids. Two thirds of the way, one of the yaks collapses on the path, exhausted, and is unloaded by Lobsang and abandoned."

“Four days later, we stop some 14,000 feet above sea level at the last camp in Nepal...The next day when we reach the pass. The weather turns foul again, but this time the men are no longer worried. They are back in their own country and from here on the trip will be downhill or on flat land. The high-lying plateaus of Tibet stretch out before them in the distance. It will take six more days for the caravans to reach their villages."

Caravans on the Karakoram Pass

Bridge on caravan route

One of the Himalayan region's most famous caravans traveled for 34 days over 18,290-foot Karakoram Pass between Ladakh in what is now India and the Silk Road oasis towns of Yarkand and Kashgar in western China. The caravan traded cotton, pearls, spices, wools, dyes such as indigo and brocades from India for silk, tea, carpets, gold, musk and medicines from China. The caravans operated for hundreds of years and continued until the hostilities between India and China closed the Karakoram Pass in the early 1960s. [Source: W.E. Garret, National Geographic, May 1963]

Between 30 and 100 horses, Bactrian camels, yaks and sheep were used to transport goods on the 30- to 40- day one way journey. The caravaners said there was little danger of getting lost and they were seldom bothered by bandits in the frigid highlands. In fact they often ferried their loads to the pass and left them there unguarded until the snow on the pass cleared. Then they would ferry their goods down the other side. Sometimes some of their merchandise was left unattended for an entire year.

The Karakoram caravan trails were so demanding that the noses of some of the mules and ponies had to be slit open to allow them to breath better. One of the last caravaners, a man named Hajji Tokta, told National Geographic magazine, "Bleached bones of animals and men regularly marked the trail. It is only by the grace of God my own are not strewn there with them. In a bad fall near the pass I broke my hip. Luckily, a companion stayed behind with me. It was a month until I could be moved. We nearly starved." While he was recuperating in Ladakh the pass was closed and he never again saw his wife or family, who lived on the other side in China.

Image Sources: Snowland cuckoo, Picasaweb and Purdue University.

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2022