ECONOMY OF TIBET

Agriculture and livestock breeding are the backbone of the Tibetan economy. The Tibetan plateau contains huge pastoral areas. Green pears, goats, caterpillar fungus and herbal medicine are important sources of income. Highland barley, peas, horse beans, jute (fibers from a plant), and beets are major crops. Its industries include handicrafts, mining and agricultural machinery. Tourism is big in Tibet. chinaculture.org, Chinadaily.com.cn, Ministry of Culture, P.R.China]

Agriculture and livestock breeding are the backbone of the Tibetan economy. The Tibetan plateau contains huge pastoral areas. Green pears, goats, caterpillar fungus and herbal medicine are important sources of income. Highland barley, peas, horse beans, jute (fibers from a plant), and beets are major crops. Its industries include handicrafts, mining and agricultural machinery. Tourism is big in Tibet. chinaculture.org, Chinadaily.com.cn, Ministry of Culture, P.R.China]

A report issued by the Beijing-based China Tibetology Research Center in March 2009 said that more than more than 90 percent of Tibet's financial revenue and over 70 percent of its fixed assets input rely on the central government's financial transfers, as well as assistance from other provinces and cities. [Source: Xinhua News Agency March 31, 2009]

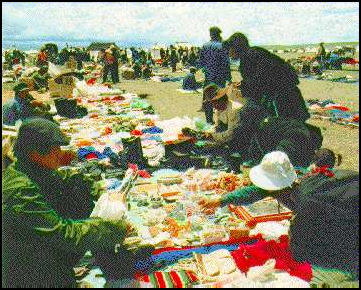

Rebecca R. French wrote: Traditionally, The large urban centers, such as the capital city of Lhasa, had daily markets displaying goods from all over the world. Particular areas of Tibet were well known for the production of certain crops or the manufacture of certain items or raw products. For example, bamboo for pens and high-quality paper came from the southeast, excellent horses from the northeast, wood products from the east, and gold, turquoise, and other gems from two or three specific areas in the south and west. Currently, most of the manufactured products in Tibet come from urban centers in the PRC, but local markets in the rural areas continue to allow for pastoralist-peasant exchange. [Source: Rebecca R. French, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

Tibet has traditionally been the home of a subsistence agriculture and herding economy. For the most part there was no currency, only barter until 1960s. The feudal system has only recently been displaced. The Dalai Lama once said: “Tibet is economically backward although spiritually highly advanced. But spiritual [strength] alone cannot fill our stomach. So we need economic development.” Commenting on the impact of economic growth on spirituality one Tibetan monk told the Asahi Shimbun that as Tibet’s “economy develops, a growing number of people are praying for their own personal happiness. People’s spirits have become poorer.”

The Tibetan economy focuses on plateau animal husbandry and farming. Sheep, goat and yak are their main domestic animals. According to the Chinese government: In some big towns and monasteries, there were a few carpenters, blacksmiths, stone carvers and weavers. They, too, had to perform services and pay taxes to manorial lords and were looked down upon by other people. [Source: China.org china.org |]

Tibet is richly endowed with energy and mineral resources (See Below). Up until the mid 1990s most consumer goods in Tibet were smuggled in from Nepal. Now Tibetan shops run by Muslim Huis sell a wide variety of goods, including eggs from Gansu, bananas from the coast, and American style shampoo from Shanghai.

See Separate Articles: ECONOMY OF TIBET, BUSINESS, MASS LABOR, INDUSTRIES factsanddetails.com; AGRICULTURE AND LIVESTOCK IN TIBET factsanddetails.com; CATERPILLAR FUNGUS (CORDYCEPS): HEALTH BENEFITS, TRADE AND MURDER factsanddetails.com; TOURISM IN TIBET factsanddetails.com; NATURAL RESOURCES, MINING AND OPPOSITION TO IT IN TIBET factsanddetails.com; ENERGY IN TIBET: HYDRO, SOLAR, GEOTHERMAL AND GAS factsanddetails.com; TRANSPORTATION IN TIBET: MOTORCYCLES, HORSES AND YAK CARAVANS factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN TRAINS: ROUTES, CONSTRUCTION AND IMPACT factsanddetails.com; articles under TIBETAN GOVERNMENT, SERVICES AND ECONOMICS factsanddetails.com ; TIBETAN HERDERS AND NOMADS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: CNN report on China Exploiting Tibetan Resources money.cnn.com ; China Daily report on Huge Mineral Resources in Tibet chinadaily.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Economy of Tibet: Transformation from a Traditional to a Modern Economy” by Luo Li Amazon.com; “Industrial Parks in Tibet Kindle Edition” by Charles Chaw Amazon.com ; “Geographical Diversions: Tibetan Trade, Global Transactions” by Tina Harris Amazon.com “Taming Tibet: Landscape Transformation and the Gift of Chinese Development” by Emily Yeh | Amazon.com; “The Disempowered Development of Tibet in China: A Study in the Economics of Marginalization” by Andrew Martin Fischer Amazon.com; “Mining Tibet: Mineral Exploitation in Tibetan Areas of the PRC” by Jane Caple Amazon.com; “Tibet A Land of Snows Rich in Precious Stones and Mineral Resources” by Jigme Lhundup Amazon.com; “Tibet Natural Resources and Scenery” by Li Mingsen and Yang Yichou Amazon.com; “Resource Exploitation and Ecological Protection in Tibet” by New Star Publishers Amazon.com; “Spoiling Tibet: China and Resource Nationalism on the Roof of the World” by Gabriel Lafitte and Paul French Amazon.com;

Trade and the China-Tibet Tea Horse Road

There is evidence of Tibetans do extensive trading over a wide area as far back as the A.D. seventh century A.D. Branches of the Silk Road traversed the Tibetan Plateau linked China, India, Nepal, and Central Asia. Among the products traded were animals, animal products, honey, salt, borax, herbs, gemstones, and metal in exchange for silk, paper, ink, tea, and manufactured iron and steel products. The government granted lucrative yearly monopolies on products such as salt. Since 1950 trade has been regulated by Communist China. [Source: Rebecca R. French, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

For many centuries the Tea Horse Road was a thoroughfare of commerce, the main link between China and Tibet. Mark Jenkins wrote in National Geographic, “The ancient passageway once stretched almost 1,400 miles across the chest of Cathay, from Yaan, in the tea-growing region of Sichuan Province, to Lhasa, the almost 12,000-foot-high capital of Tibet. One of the highest, harshest trails in Asia, it marched up out of China's verdant valleys, traversed the wind-stripped, snow-scoured Tibetan Plateau, forded the freezing Yangtze, Mekong, and Salween Rivers, sliced into the mysterious Nyainqentanglha Mountains, ascended four deadly 17,000-foot passes, and finally dropped into the holy Tibetan city.” [Source: Mark Jenkins, National Geographic, May 2010]

“Tea was first brought to Tibet, legend has it, when Tang dynasty Princess Wen Cheng married Tibetan King Songtsen Gampo in A.D. 641. Tibetan royalty and nomads alike took to tea for good reasons. It was a hot beverage in a cold climate where the only other options were snowmelt, yak or goat milk, barley milk, or chang (barley beer). A cup of yak butter tea — with its distinctive salty, slightly oily, sharp taste — provided a mini-meal for herders warming themselves over yak dung fires in a windswept hinterland.”

The tea that traveled to Tibet along the Tea Horse Road was the crudest form of the beverage. Tea is made from Camellia sinensis, a subtropical evergreen shrub. But while green tea is made from unoxidized buds and leaves, brick tea bound for Tibet, to this day, is made from the plant's large tough leaves, twigs, and stems. It is the most bitter and least smooth of all teas. After several cycles of steaming and drying, the tea is mixed with gluey rice water, pressed into molds, and dried. Bricks of black tea weigh from one to six pounds and are still sold throughout modern Tibet.” [Ibid]

See Tea Horse Road Under TRANSPORTATION IN TIBET: MOTORCYCLES, HORSES AND YAK CARAVANS factsanddetails.com

Economic Improvements in Tibet

.jpg)

Sail assisted wheelbarrows Tibet's gross domestic product (GDP) grew at a 12 percent annual rate, faster than the robust Chinese national average, in the 2000s. GDP reached 21.2 billion yuan (almost $3 billion) in 2004, a 19 fold increase from 1964. Much of the increase is attributed to government aid and the influx of Han Chinese who have created more economic opportunities, mostly for themselves but also some Tibetans too.

The Chinese government claims the growth rate in Tibet was around 9 percent in the late 1990s and early 2000s on par with that in China as a whole. Most of the growth has been concentrated in urban areas, particularly among Chinese immigrants. The urban income is about $650 a year, five times as high as the countryside. More recently, the economy in Tibet has grown in double digit numbers, higher than those of China as a whole. Between 2001 and 2005, Tibet experienced average annual growth of 12 percent. The opening of the railway to Tibet helped boost growth to 13.2 percent in 2006.

Economic reforms have raised the standard of living of many Tibetans. But large numbers have also been left out. Annual income quadrupled to $1,076 between 1986 and 2006. Yet unemployment remains at around 10.3 percent, higher than the rest of the nation. Many of the unemployed are Tibetans, some of whom hang out pool halls during the day and get drunk at night.

Beijing seems to be banking on the idea that economic prosperity will weaken the ties between Tibetans and their culture and religion and make it easier for the government to control them. But there are limits. One Tibetan truck driver told the Times of London, “Our lives are much better now — we can afford our own houses. It’s just that I don’t like the Chinese government.”

Robert Barnett, a scholar of Tibet at Columbia University, told the New York Times the goal of maintaining double-digit growth in the region had worsened ethnic tensions. "Of course, they achieved that, but it was disastrous," he said. "They had no priority on local human resources, so of course they relied on outside labor, and sucked in large migration into the towns."

Tibet's GDP Grows Almost 200 Times Between 1959 to 2018

Tibet's gross domestic product (GDP) in 2018 reached 147.76 billion yuan (US$22 billion) about 191 times more than the 1959 figure calculated at comparable prices, according to a white paper released by China's State Council Information Office. Xinhua reported: The added value of agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, fisheries and related service industries rose from 128 million yuan in 1959 to 13.41 billion yuan in 2018. Grain yield increased from 182,900 tonnes in 1959 to more than 1 million tonnes in 2018, it said. [Source: Xinhua, March 27, 2019]

Tibet's modern industry started from scratch and has grown steadily, the white paper said, adding that Tibet's industrial added value increased from 15 million yuan in 1959 to 11.45 billion yuan in 2018. Tibet has accomplished a fundamental change and optimization in economic structure, the white paper said, noting that the share of added value from primary industry in GDP dropped from 73.6 percent in 1959 to 8.8 percent in 2018, while the share of secondary industry rose to 42.5 percent and the share of tertiary industry increased to 48.7 percent.

The tertiary industry in Tibet is thriving and tourism is developing rapidly, the white paper said, noting that in 2018, Tibet received 33.69 million tourist visits, with a total tourism revenue of 49 billion yuan More than 100,000 farmers and herdsmen have earned more through tourism and Tibet has become an international tourist destination, it said. Infrastructure has been improved in Tibet, as a comprehensive transportation network composed of highways, railways and air routes has been formed, it added.

Labor and Work in Tibet

Traditionally, there were distinctions in wealth and status among both the peasants and nomads. Hired laborers and servants freed wealthier families from most of the manual labor of daily life. In larger cities, butchering, metalworking, and other low-status crafts were traditionally confined to particular groups. [Source: Rebecca R. French, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

In the 1990s and 2000s, some of the menial labor on construction sites and road crews was done by teenage girls who earned about $2.50 a day. They shoveled dirt, carries cement, painted walls and scrubbed floors 12 hours a day, seven days a week. Most didn’t complain, saying that life is harder in their home villages.

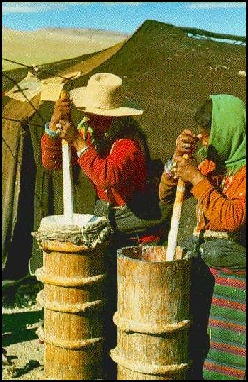

In the countryside adults work about 49 hours a week (7 hours a day, 7 days a week). Women often throw their young children in slings and toss them on their back when they perform chores such as butter churning. In the morning men cut firewood and bring anything of value (such as berries or mushrooms) that can be found along the way. Tibetans in the northern Yunnan and western Sichuan make their living by hunting wild goats, growing wheat and barely, panning for gold and drying salt in terraces along the rivers.

In July 2010, Tibet raised its monthly minimum wages by up to 35 percent. Xinhua reported: The move was approved by the autonomous regional government. The hike added 220 yuan (US$32.4) to the monthly minimum wages that vary from 630 yuan to 730 yuan in different parts of the region. In addition, the minimum per-hour wages were also raised to 7.5 yuan and 8.5 yuan from the previous 5.5 yuan and 6.5 yuan with an increase of up to 36 percent. The wage hike is the second since 2007. [Source: Xinhua, July 27, 2010]

Mass Labor in Tibet

In 2020, Cate Cadell of Reuters wrote: China is pushing growing numbers of Tibetan rural laborers off the land and into recently built military-style training centers where they are turned into factory workers, mirroring a program in the western Xinjiang region that rights groups have branded coercive labor. Beijing has set quotas for the mass transfer of rural laborers within Tibet and to other parts of China, according to over a hundred state media reports, policy documents from government bureaus in Tibet and procurement requests released between 2016-2020 and reviewed by Reuters. The quota effort marks a rapid expansion of an initiative designed to provide loyal workers for Chinese industry. [Source: Cate Cadell, Reuters, September 22, 2020]

“A notice posted to the website of Tibet's regional government website in August 2020 said over half a million people were trained as part of the project in the first seven months of 2020 — around 15 percent of the region's population. Of this total, almost 50,000 have been transferred into jobs within Tibet, and several thousand have been sent to other parts of China. Many end up in low paid work, including textile manufacturing, construction and agriculture. “This is now, in my opinion, the strongest, most clear and targeted attack on traditional Tibetan livelihoods that we have seen almost since the Cultural Revolution" of 1966 to 1976, said Adrian Zenz, an independent Tibet and Xinjiang researcher, who compiled the core findings about the program. These are detailed in a report released this week by the Jamestown Foundation. "It's a coercive lifestyle change from nomadism and farming to wage labor." Reuters, corroborated Zenz's findings and found additional policy documents, company reports, procurement filings and state media reports that describe the program.

“In a statement to Reuters, China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs strongly denied the involvement of forced labor, and said China is a country with rule of law and that workers are voluntary and properly compensated. “What these people with ulterior motives are calling 'forced labor' simply does not exist. We hope the international community will distinguish right from wrong, respect facts, and not be fooled by lies," it said.

“Moving surplus rural labor into industry is a key part of China's drive to boost the economy and reduce poverty. But in areas like Xinjiang and Tibet, with large ethnic populations and a history of unrest, rights groups say the programs include an outsized emphasis on ideological training. And the government quotas and military-style management, they say, suggest the transfers have coercive elements.

“Around 70 percent of Tibet's population is classified as rural, according to 2018 figures from China's National Bureau of Statistics. This includes a large proportion of subsistence farmers, posing a challenge for China's poverty alleviation program, which measures its success on levels of basic income. China has pledged to eradicate rural poverty in the country by the end of 2020. “In order to cope with the increasing downward economic pressure on the employment income of rural workers, we will now increase the intensity of precision skills training ... and carry out organized and large-scale transfer of employment across provinces, regions and cities," said a working plan released by Tibet's Human Resources and Social Security Department in July. The plan included 2020 quotas for the program in different areas.

How Mass Labor in Tibet Works

Cate Cadell of Reuters wrote: “While there has been some evidence of military-style training and labor transfers in Tibet in the past, this new, enlarged program represents the first on a mass scale and the first to openly set quotas for transfers outside the region. A key element, described in multiple regional policy documents, involves sending officials into villages and townships to gather data on rural laborers and conduct education activities, aimed at building loyalty. [Source: Cate Cadell, Reuters, September 22, 2020]

“State media described one such operation in villages near the Tibetan capital, Lhasa. Officials carried out over a thousand anti-separatism education sessions, according to the state media report, "allowing the people of all ethnic groups to feel the care and concern of the Party Central Committee," referring to China's ruling Communist Party. The report said the sessions included songs, dances and sketches in "easy to understand language." Such "education" work took place prior to the rollout of the wider transfers this year. The model is similar to Xinjiang, and researchers say a key link between the two is the former Tibet Communist Party Secretary Chen Quanguo, who took over the same post in Xinjiang in 2016 and spearheaded the development of Xinjiang's camp system. “In Tibet, he was doing a slightly lower level, under the radar, version of what was implemented in Xinjiang," said Allen Carlson, Associate Professor in Cornell University's Government Department.

“Some of the policy documents and state media reports reviewed by Reuters make reference to unspecified punishments for officials who fail to meet their quotas. One prefecture level implementation plan called for "strict reward and punishment measures" for officials. As in Xinjiang, private intermediaries, such as agents and companies, that organize transfers can receive subsidies set at 500 yuan ($74) for each laborer moved out of the region and 300 yuan ($44) for those placed within Tibet, according to regional and prefecture level notices.

“Officials have previously said that labor transfer programs in other parts of China are voluntary, and many of the Tibetan government documents also mention mechanisms to ensure laborers' rights, but they don't provide details. Advocates, rights groups and researchers say it's unlikely laborers are able to decline work placements, though they acknowledge that some may be voluntary. “These recent announcements dramatically and dangerously expand these programs, including 'thought training' with the government's coordination, and represent a dangerous escalation," said Matteo Mecacci, president of U.S. based advocacy group, the International Campaign for Tibet.

“The government documents reviewed by Reuters put a strong emphasis on ideological education to correct the "thinking concepts" of laborers. "There is the assertion that minorities are low in discipline, that their minds must be changed, that they must be convinced to participate," said Zenz, the Tibet-Xinjiang researcher based in Minnesota. One policy document, posted on the website of the Nagqu City government in Tibet's east in December 2018, reveals early goals for the plan and sheds light on the approach. It describes how officials visited villages to collect data on 57,800 laborers. Their aim was to tackle "can't do, don't want to do and don't dare to do" attitudes toward work, the document says. It calls for unspecified measures to "effectively eliminate 'lazy people.'" A report released in January by the Tibetan arm of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, a high-profile advisory body to the government, describes internal discussions on strategies to tackle the "mental poverty" of rural laborers, including sending teams of officials into villages to carry out education and "guide the masses to create a happy life with their hardworking hands."

Military-Style Training for Mass Labor in Tibet

Cate Cadell of Reuters wrote: “Rural workers who are moved into vocational training centers receive ideological education — what China calls "military-style" training — according to multiple Tibetan regional and district-level policy documents describing the program in late 2019 and 2020. The training emphasises strict discipline, and participants are required to perform military drills and dress in uniforms. [Source: Cate Cadell, Reuters, September 22, 2020]

“It is not clear what proportion of participants in the labor transfer program undergo such military-style training. But policy documents from Ngari, Xigatze and Shannan, three districts which account for around a third of Tibet's population, call for the "vigorous promotion of military-style training." Region-wide policy notices also make reference to this training method. Small-scale versions of similar military-style training initiatives have existed in the region for over a decade, but construction of new facilities increased sharply in 2016, and recent policy documents call for more investment in such sites. A review of satellite imagery and documents relating to over a dozen facilities in different districts in Tibet shows that some are built near to or within existing vocational centers.

“The policy documents describe a teaching program that combines skills education, legal education and "gratitude education," designed to boost loyalty to the Party. James Liebold, professor at Australia's La Trobe University who specializes in Tibet and Xinjiang, says there are different levels of military-style training, with some less restrictive than others, but that there is a focus on conformity. “Tibetans are seen as lazy, backward, slow or dirty, and so what they want to do is to get them Marching to the same beat... That's a big part of this type of military-style education."In eastern Tibet's Chamdo district, where some of the earliest military-style training programs emerged, state media images from 2016 show laborers lining up in drill formation in military fatigues. In images published by state media in July this year, waitresses in military clothing are seen training at a vocational facility in the same district. Pictures posted online from the "Chamdo Golden Sunshine Vocational Training School" show rows of basic white shed-like accommodation with blue roofs. In one image, banners hanging on the wall behind a row of graduates say the labor transfer project is overseen by the local Human Resources and Social Security Department.

“The vocational skills learned by trainees include textiles, construction, agriculture and ethnic handicrafts. One vocational center describes elements of training including "Mandarin language, legal training and political education." A separate regional policy document says the goal is to "gradually realize the transition from 'I must work' to 'I want to work.'" Regional and prefecture level policy documents place an emphasis on training batches of workers for specific companies or projects. Rights groups say this on-demand approach increases the likelihood that the programs are coercive.

“Tibetan state media reports say that in 2020 some of the workers transferred outside of Tibet were sent to construction projects in Qinghai and Sichuan. Others transferred within Tibet were trained in textiles, security and agricultural production work. Regional Tibetan government policy notices and prefecture implementation plans provide local government offices with quotas for 2020, including for Tibetan workers sent to other parts of China. Larger districts are expected to supply more workers to other areas of the country — 1,000 from the Tibetan capital Lhasa, 1,400 from Shigatse, and 800 from Shannan.

Reuters, reviewed policy notices put out by Tibet and a dozen other provinces that have accepted Tibetan laborers. These documents reveal that workers are often moved in groups and stay in collective accommodation. Local government documents inside Tibet and in three other provinces say workers remain in centralised accommodation after they are transferred, separated from other workers and under supervision. One state media document, describing a transfer within the region, referred to it as a "point to point 'nanny' service."

“The Tibetan Human Resources and Social Security Department noted in July that people are grouped into teams of 10 to 30. They travel with team leaders and are managed by "employment liaison services." The department said the groups are tightly managed, especially when moving outside Tibet, where the liaison officers are responsible for carrying out "further education activities and reducing homesickness complexes." It said the government is responsible for caring for "left-behind women, children and the elderly."

Chinese Get the Good Jobs in Tibet

Tibetans complain they do not have many job or career opportunities. Those that get government jobs never seem to be able to rise above the deputy level. One Tibetan student told the New York Times, “I’m not even sure I can get a job after graduation.” In October 2006, several hundred young educated Tibetans gathered in front of the local government administrative building to protest the fact that they were educated and qualified but jobs went to Han Chinese not them.

Chinese dominate the Lhasa economy. Most of the shop keepers, taxi drivers are Han Chinese. In Lhasa, nearly all the taxi drivers are Chinese. Few Tibetans can afford the $20,000 needed to buy a car.

Many Tibetans lack good Chinese language skills, a basic requirement for jobs in China. Tibetan guides lose their license if they can’t pass an annual exam in Mandarin.

See Lhasa

Business in Tibet

Tibetan market

The number of businesses in Tibet rose from 500 in 1993 to 41,000 in 2003. The Chinese government has offered tax breaks and other incentive to foreign investors who are willing invest in Tibet. Joint ventures for making motorcycle engines and cashmere knitwear have been set up. Beijing has also ordered every Chinese province and several state companies to invest in Tibet. Lhasa has a stock exchange.

Many of the businesses in Tibet are owned by Chinese. Many have few Tibetan employees or or even Tibetan customers. Almost everything that is sold in Tibet comes from China. Tibetans say the Chinese have better guanxi (connections) and more developed business sense. One Tibetan told Atlantic Monthly, "Those people know how to do business. We Tibetans don’t know how do it. If something is supposed to be five yuan, we say it's five yuan. But Sichuanese will say ten."

Tibetans have traditionally not been very ambitious. In many ways Buddhism teaches one to accept their lot in life and look for happiness in future lives. One Tibetan yak trader told the Washington Post, “I don’t care about Tibet very much. We’ve been influenced by the Han people. Some Tibetan are poor because they are not brave enough. Some don’t have any business sense. Some spend their money too quickly.” See Cultural Differences

Tibetans have traditionally traded animals, animal products, honey, salt, borax, herbs, gemstones, and metal in exchange for slk, paper, ink, tea, and manufactured goods. Trade was sometimes carried out by pilgrims while on pilgrimages. Tibetan traders haul barley and meat in wheelbarrows.

To earn extra money people collect wild flowers, herbs and other plants that can be sold as traditional medicines.

See Rich

Shopping in Lhasa

yak hair rug

There are many department stores in Lhasa, mostly on Yuthok Lu that supply everyday needs. For example, Lhasa Department Store, located on the west end of Yuthok Lu, is the largest and best known department store in Lhasa. There are also some supermarkets in Lhasa, such as Hongyan Supermarket Chains mainly distributed in Lhasa downtown. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org tibettravel.org ]

Barkhor Street is a traditional Tibetan shopping center, where shopkeepers with small shops and stalls on the street supply more traditional and fascinating Tibetan artifacts and handicrafts. These items include prayer flags, Buddha figures, conch-shell trumpets, rosaries, amulets, fur hats, horse bells, bridles, copper teapots, wooden bowls, inlaid knives, and jewelry inlaid with turquoise and other gems. The Tibetan knife is a special item that is not allowed on airplane, but you can certainly mail it to your home by post office.

Do not forget to carefully examine jewelry for quality. Though lots of jewelry of excellent quality is available, some is coarse and poor in quality. It is very easy to find appealing items that are uniquely Tibetan. Exotic Tibetan opera masks and costumes are really attractive. Brightly colored, beautifully homespun Tibetan rugs and khaddar are also popular souvenirs. Tibetan carpet can be bought at the Tash Delek Tibetan Rug Factory.

Shopping in Bakhor and Lhasa See LHASA: IT'S HISTORY, DEVELOPMENT, AND TOURISM factsanddetails.com ; MAIN SIGHTS IN LHASA: JOKHANG, NORBULINGA AND BAKHOR factsanddetails.com

Industries in Tibet

Tibet's industries include handicrafts, mining and agricultural machinery. Most manufactured goods come from China. Traditional Tibetan trades include flour milling, canvas painting, paper making, rope braiding, wool and fiber processing, weaving and textile production, tanning, metalwork, carpentry, and wood carving. Small scale and household production has traditionally been the norm. Large monasteries produce books, religious manuscripts and religious objects on an industrial scale.

According to the Chinese government: Rapid developments have been reported by all trades and services in Tibet. Starting from scratch, Tibet's industry boasted more than 300 factories and mines by the end of 1984, covering power generating, metallurgy, woolen textiles, machinery, chemical engineering, pharmaceuticals, paper making and printing. They turned out more than 80 products, with a total value of 168 million yuan a year. The bleak and desolate Bangon, Markam and Qaidam areas have become major industrial centers. [Source: China.org china.org |]

Dege Printing House in Dege in western Sichuan is good example of a traditional industry in Tibet. Built between 1729 and 1750, this three-story wooden structure stores 80 percent of the Tibetan literary culture, and produces a wide range of texts for monasteries, libraries, study centers and Tibetan colleges, which people from all over Tibet come to pick up. The Dege Printing House is regarded as a sacred site. Pilgrims seek it out and walk clockwise around it with prayer wheels in their hands. More than 210,000 hand-craved wooden blocks, some of which were carved in the 16th century, are stored there. Printing stopped in 1950s when Dege came under Chinese rule, but was spared by the Red Guards, while other Tibetan buildings were destroyed, on orders of Zhou Enlai

See Dege Under GLACIERS, BIG MOUNTAINS AND TIBETAN AREAS OF WESTERN SICHUAN factsanddetails.com Also See THANGKAS: TYPES, SUBJECTS, MATERIALS AND MAKING THEM factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN CRAFTS factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN JEWELRY, MASKS AND OBJECTS DE ART factsanddetails.com

Weaving in Tibet

Weaving is one of the most developed traditional industries that takes place outside the monasteries. Many homes have a looms and many of the garments that people wear are made at home. Young women spin raw wool into yarn. Many Tibetan women still twist yarn by hand with a distaff, the same method employed by the ancient Greeks. Wide bands are woven into carpets by men. Narrow bands are used for belts.

Clothing is generally made from “nambu” — wool spun from yak or sheep hair and very tightly woven in narrow strips. Nambu is usually sold in lengths called "dhomaos." One dhompa is equal to the distance between a man’s two hands when he opens his arms as wide as he can.

Pashmina wool — the soft, warm fiber from Himalayan goats — has become world famous over the past couple of decades, It is sold in boutiques from Manhattan to Paris. In 2000, Nepal exported $103 million worth of pashmina wool. By last year, exports had slumped to $18 million. Traders say the main reason for the plunge was competition from inexpensive mass-produced imitations made from synthetic fabrics and cheaper wool. [Source: Binaj Gurubacharya, Associated Press, May 6, 2011]

See Separate Article TIBETAN CLOTHES: TYPES, ROBES, PULU, HATS AND BOOTS factsanddetails.com

Tibetan Weaving Business Adapted to Modern Life

In 2012, Ruby Yang, an Academy Award-winning documentary filmmaker, came across a unique Tibetan business — Norlha, a textile workshop in the village of Zorge Ritoma, in the Gansu Province part of Amdo, that is combined with Norden, a luxury campsite near the Buddhist monastery of Labrang, whose purpose is to raise revenue for Norlha. [Source: Edward Wong, Sinosphere, New York Times, August 24, 2016] . The workshop had been founded around 2006 by a Tibetan-American family. It employed many women from the village, which was made up of nomadic households. Yang told the New York Times “It’s a way for nomads to transition to modern life. Some of the families, especially women, can have a stable job. It’s very difficult for women to find a job outside of the village. They have to travel so far. In the village, they now have a job that makes decent money. And it also helps for the men. Now the nomads are changing. The younger people might not want to be a nomad anymore. If one member of the family can have a stable income while another person decides to become a nomad, the family can be better off. That’s modern life. One goes into modern industry.

“The products they make are absolutely beautiful. They are taking the traditional skills they have and marketing it to the outside world. Few people know nomads can make such beautiful products. People don’t know they have been doing it for centuries. “I was able to some spend time with the nomads. Even though a lot of them haven’t had a real education, a lot of the people in the workshop, they know how to do these things. And they have only had a few years of education.

“In Hong Kong, people spend hours and hours on tutoring, on studying for exams, on trying to get into the best schools. And they might not learn anything. Here, they don’t have much schooling, but they are doing the best job. “I also noticed that a lot of them, when they weave, they also pray. They have their prayer beads and pray with those when they don’t need to use both hands for their work.

“The thing is, they don’t have to leave the village. They can walk to the workshop in five minutes. I think that’s so important for them, so they can be with their family. They can have a job and spend time with their family. If they have to go to the city and have to leave their children, they don’t necessarily have the income to hire a babysitter. “For a lot of nomads to go to the city, to go to modern life, I don’t think they like it. It’s a big shock for them. It’s too huge a shock.”

Image Sources: Purdue University, Antique Tibet

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2022