TIBETAN THANGKAS

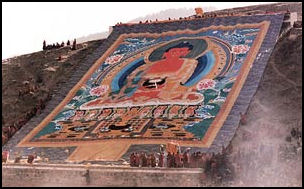

Thangka at Labrang monestary

Thangkas are traditional Tibetan painted tapestries or cloth scrolls designed as aids in meditation, and also serving as signs of devotion to Buddhism and may be an object of worship. Painted on cotton or linen, they usually contain images of deities and religious figures and often are representations of spiritual or historical events. As is true with mandalas both making a thangka and gazing at one are regarded as forms of meditation. The idea is to lose oneself in thangka not express it. Traditionally, they were never bought or sold. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, March 29, 2009]

Thangkas (also spelled tankas, tangkas) typically feature explosions of bright colors. The common size of thangkas, with a scroll at the bottom, is usually 75 centimeters long and 50 centimeters wide. Banner style thangkas are 1.1 meters long and about 3.5 meters wide. In Tibetan, thang means "unfolding" or "displaying," and thangka means "silk, satin, or cloth painting scroll." Unlike an oil painting or acrylic painting, the thankga is not a flat creation, but consists of a painted or embroidered picture panel, over which a textile is mounted, and then over which is laid a cover, usually cotton, but sometimes silk or linen. Generally, thankgas last a very long time and retain much of their lustre, but because of their delicate nature, they have to be kept in dry places so as to prevent the quality of the silk from being affected by moisture. [Source: chinaculture.org, Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

Thangkas are usually rectangular in shape, although some depicting mandala are square, and generally have embroidery around the edges. They are usually hung in monasteries, temples or homes. In Buddhist monasteries, they are often used to focus meditation. In Tibet, thangkas are frequently the center of Buddhist religious ceremonies. Pilgrims throw money to the thangka to show their respect. Most thangkas are designed to be portable. Before they are transported they are mounted on a brace and rolled up between two sticks. They have traditionally been carried by nomads and used by holy men, teachers and healers. Some huge ones are made to be unfurled annually at festivals.. One thangka made after 15 months of work and $2.4 million was 148 feet high, 115 feet wide and weighed over three tons.

See Separate Articles TIBETAN ART factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN PAINTING factsanddetails.com; MANDALAS: TYPES, MEANING AND MAKING THEM factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN SCULPTURE factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN CRAFTS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Himalayan Art Resources himalayanart.org ; Buddha.net buddhanet.net ; Conserving Tibetan Art and Architecture asianart.com ; Guardians of the Sacred World (Tibetan Manuscript Covers) asianart.com ; Wikipedia article on Mandalas Wikipedia ; Introduction to Mandalas kalachakranet.org ; Books: “Wisdom and Compassion: The Sacred Art of Tibet” by M.M. Rhie and Robert Thurman; “The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs” and “The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols” by Robert Beer; Video: “Mystic Vision, Sacred Art: The Tradition of Thangka Painting”,1996, 28 minutes. Examines every step of the process of painting the scrolled Tibetan Buddhist devotional images called thangkas. Illustrates the preparation of the painting surface, the grinding of the pigments, and the drawing of the sacred image and its completion in brilliant color. Distributor: Documentary Educational Resources, 101 Morse Street, Watertown, MA 02172, (800) 569–6621.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Thangkas: “Tibetan Paintings: A Study of Tibetan Thankas, Eleventh to Nineteenth Centuries” by Pratapaditya Pal, with lots of illustrations Amazon.com; “Tibetan Thangka Painting: Methods and Materials” by David Jackson and Janice Jackson Amazon.com; Painting: “Tibetan Painting” by Hugo Kreijer Amazon.com; “Painting Traditions of the Drigung Kagyu School” by David P. Jackson, Christian Luczanits, et al. Amazon.com; “Mirror of the Buddha: Early Portraits from Tibet” by David P. Jackson Amazon.com; Art: “Wisdom and Compassion: The Sacred Art of Tibet” by M.M. Rhie and Robert Thurman Amazon.com . “Images of Enlightenment: Tibetan Art in Practice” by Jonathan Landaw and Andy Weber Amazon.com; “Tibetan Art” by Lokesh Chandra Amazon.com; “Buddhist Art of Tibet: In Milarepa's Footsteps: by Etienne Bock, Jean-Marc Falcombello, et al. Amazon.com; “Art of Tibet” by Robert E. Fisher Amazon.com; Symbols and Iconography: “The Tibetan Iconography of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, and Other Deities: A Unique Pantheon by Lokash Chandra and Fredrick W. Bunce Amazon.com; “The Way of the Bodhisattva: Shambhala” by Shantideva, Padmakara Translation Group, et al. Amazon.com; Gods, Goddesses & Religious Symbols of Hinduism, Buddhism & Tantrism [Including Tibetan Deities]by Trilok Chandra Majupuria and Rohit Kumar Amazon.com;“The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs” by Robert Beer Amazon.com; “The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols” by Robert Beer Amazon.com; “Buddhist Symbols in Tibetan Culture : An Investigation of the Nine Best-Known Groups of Symbols” by Dagyab Rinpoche and Robert A. F. Thurman Amazon.com

Types of Thangka

Thangkas can be made in a wide variety of techniques: silk tapestry with cut designs, color printing, embroidery, brocade, appliqué, and pearl inlay. There four main kinds of thangka are: 1) embroidered thangka; 2) lacquered thangka; 3) applique thangka; and 4) precious bead thangka. The latter are decorated with pearls, coral, turquoise, gold and silver.

Thangkas comes in various sizes and types. Small ones are only several centimeters wide, and big ones are tens of meters across. The giant Thangka kept in the Potala Palace is more than 50 meters long. Among the different types are embroidered Thangka, applique Thangka, tapestries done with fine silks and gold threads, Thangka with silk-woven pictures, and Thangka with piled embroidery. The most characteristic is the Thangka with "piled embroidery". It is composed of carefully chosen brocade with different colors and designs. All the threads sewn on the cloth are made by tangling colored silk and horse tail hair. Some are partly inlaid with jewelry. The artistry and craftsmanship can be very complicated and exquisite. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities]

Based on the material, thangkas can be divided into two types:1) gos-thang, made of silk, and; 2) bris-thang, made of pigment. The gos-thang is printed on the canvas while the bris-thang is painted on the canvas, The largest bris-thang is 3 meters long and 2 meters wide while the smallest one is about 30 centimeters long and 20 centimeters wide. The gos-thang thangka is called gos-sku. It is too big to hang up and is only used in some special religious rituals. At Potala Palace, there is a gos-sku that is 55.8 meters long and 46.81 meters wide, made during the 5th Dalai Lama period 17th century.. [Source: chinaculture.org, Chinadaily.com.cn, Ministry of Culture, P.R.China]

Gos-thang can be divided into five classes based on the different kinds of silk used:

1) Tshem-drub-ma is made of different kinds of silk woven by hand.

2) Lhan-dr-ub-ma or dras-drub-ma: To make this kind of thangka, different kinds of silk are first cut into different shapes and then connected with needles.

3) Lhan-thabs-ma: This kind is a little similar to the second, but to make this one, different shapes of silk are glued together by glue water.

4) Thag-drub-ma: This thangka is woven by hand.

5) Dpar-ma: To make this kind of thangka, a molding board is necessary to print the pictures into the silk.

Bris-thang can be divided into five classes based on the background color:

1) Tsho-thang: with a multicolored background;

2) Gser-thang: with a yellow background;

3) Mtshal-thang: with a vermilion background;

4) Dpar-thang: with a black background;

5) Dpar-thang: made with water print.

There is a thangka in one of the chapels of Trandruk Monastery, representing Chenrezi at rest, made of pearls. The Thangka is two meters long and 1.2 meters wide. The weight of the whole thangka is over 1.3kg. Most importantly, this thangka is made of 29026 pieces of pearls, one diamond, two rubies, one sapphire, 0.3 grams of turquoise, eight grams of gold, and other gemstones. The thangka has been passed down generations to generations without being damaged or lost during chaos of political struggles and wars. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

History of Tibetan Thangka Art

Tibetan Thangka is a Nepalese art form exported to Tibet, it is said, in the 7th century after Princess Bhrikuti of Nepal, a daughter of King Lichchavi and a wife of Songtsan Gampo . The art form did originate in Nepal but more likely came much later than the 7th century. Early thangka were used to teach people about the lives of Buddhist figures. It is said that lamas went around preaching the dharma and carried thangka scrolls to illustrate their message. The Menri type was distinguished by its vibrant colors and a central figure surrounded by events and people in his life.

Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts from The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Buddhism was first introduced in Tibet in the seventh century as a courtreligion. However, it did not gain popular support until the early eleventh century, when Tibetan Buddhist teachers traveled to India to study at the great monasteries and famous Buddhist teachers were invited to Tibet to reform the practice of Buddhist rituals. The Pala style of eastern India influenced the art of Nepal from the eighth through the twelfth century, but had a more lasting impact in Tibet, from the twelfth through the early fifteenth century. Nepalese art also had a profound influence on that of Tibet from the thirteenth century through the fifteenth. From the fifteenth century onward, the Tibetans forged their own unique style with elements from India, Nepal, and China. [Source: Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts, The Art of South, and Southeast Asia, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York]

Chinese historians claim that Chinese painting had a profound influence on Tibetan painting in general. Starting from the 14th and 15th century, Tibetan painting had incorporated many elements from the Chinese, and during the 18th century, Chinese painting had a deep and far-stretched impact on Tibetan visual art. According to Giuseppe Tucci, by the time of the Qing Dynasty, "a new Tibetan art was then developed, which in a certain sense was a provincial echo of the Chinese 18th century's smooth ornate preciosity." [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

Because so many works in monasteries were destroyed in the Cultural Revolution and thangkas are popular with collectors more and more young people are taking up the art as a way to make money. “Commercialization has driven thangkas far from their origins, from their use as religious objects, Zhang Yasha, a teacher of fine arts at the Minzu University of China who specializes in Tibet, told the New York Times. “We see more young people learning the art because it’s lucrative.”

Content, Subjects and Functions of Tibetan Thangka Art

The content of thangkas varies quite a bit. They usually contain portraits of bodhisattvas, giant mandalas, Tibetan Buddhist gods, images of Buddhas and Jataka stories of the Buddha but may also cover or touch on historical events, biographies, religious ideas, scenery, everyday life, folklore, myths, Tibetan astrology and medicine. Typically, they depict Tibetan gods and other religious iconography such as Padmasambhava and White Tara and Green Tara, and the circle of life with people reclining in heaven and roasting in hell.The setting, the background, architectural elements, secondary figures are all executed with special aims and symbolic meaning. One thangka artist told the Japan Times, “There is no room for originality in thangka painting. The iconography, the colors, even the way you hold the brush — everything must be done just so.”

To Buddhists thanka offer a beautiful manifestation of the divine, being both visually and mentally stimulating. The featured deity or saint occupies the center while other attendant deities or monks, comparatively smaller in size, surround the central figure and along the border. Thangka images generally fall into 11 categories: 1) mandalas, 2) Tsokshing (Assembly Trees), 3) Tathagata Buddhas, 4) Patriarchs, 5) Avoliteshvara, 6) Buddha-Mother and female Bodhisattvas, 7) tutelary deities, 8) dharma-protecting deities, 9) Arhats. and 10) wrathful deities; and 11) other Bodhisattvas.

Thangka, when created properly, perform several different functions. Originally, thangka painting became popular among traveling monks because the scroll paintings were easily rolled and transported from monastery to monastery. Images of deities can be used as important teaching tools when depicting the life (or lives) of the Buddha, describing historical events concerning important Lamas, or retelling myths associated with other deities and bodhisattvas. One popular subject is The Wheel of Life, which is a visual representation of the Abhidharma teachings (Art of Enlightenment). Devotional images act as the centerpiece during a ritual or ceremony and are often used as mediums through which one can offer prayers or make requests. Overall, and perhaps most importantly, religious art is used as a meditation tool to help bring one further down the path to enlightenment. The Buddhist Vajrayana practitioner uses a thanga image of their yidam, or meditation deity, as a guide, by visualizing “themselves as being that deity, thereby internalizing the Buddha qualities (Lipton, Ragnubs).” [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

Making a Thangka

Thangkas are painted on thin sheets of linen or cotton that are tightly stretched on a rectangular wood frame and stiffened with glue and coated with a mix of lime and chalk called gesso. The paints are ideally made from natural materials, usually minerals — red from cinnabar, yellow from sulphur, blue from lapis lazuli and azurite, green from malachite — carefully mixed in their own pots with water and warm glue. Many colors have traditionally been made with special plants and minerals found in Tibet. The bright colors come from grinding materials like coral, agate, sapphire, pearl and gold. Black is derived from soot and white from kaolin. Organic materials — such chochineal (shells from a kind of insect) for red and and indigo for blue — are also used. Some are burnished with gold. Some important thangkas use considerable amounts of ground gold and gemstones as pigments.

Usually a cotton, linen or rough woolen cloth is used as a background. Silk and satin are used as backgrounds for high quality ones. Flaxen threads are sewed at edge of the background cloth, and the cloth is stretched tightly on specially made wood frame. The plaster-like gesso is spread over both the front and back of the canvas to block the holes and then scraped off to make a flat and smooth surface. Sometimes the gesso is mixed animal fat and talcum powder and smeared on with the cloth and scraped off with a mussel shell. After the cloth becomes dry thoroughly, one can paint on it. After the thangka is painted it is taken off the wood frame and mount with brocade and made into a scroll. A wooden stick is attached on the side from the bottom to the top to make it easier to hang and roll up. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities]

Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts from The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The majority of thankas and paubhas (from Nepal) were painted on primed cotton whose weave varied from the very fine to quite coarse. The first step was to stretch the cloth on a support. The fabric was then sized on one side with animal glue and mixed with kaolin, a white earth powder, to create a painting surface. The artist could then begin to lay out the painting’s composition, frequently using a grid system following strict rules of representation, scale, and arrangement. [The colors, mixed with warm animal glue (distemper) and water, had to be applied quickly before the glue 48 cooled and became too difficult to apply evenly. The finished painting was removed from its wood supports and mounted in silk borders. Source: Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts, The Art of South, and Southeast Asia, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York]

Painting a Thangka

The painting of a thangka begins with the making of a grid and outlining the entire composition in black. Often some orienting lines are drawn to guide the sketching. By following a fixed proportion, the artist creates some roughly drawn images. The details and images are worked out in advance in accordance with strict mathematical measurements.

The artist then fills in the outlines and different segments one color at a time rather than an image at a time, beginning with the background. Black, green, red, yellow, and white as the basic colors used.Usually the deep blues and greens are done first, followed by the reds and yellows. Each color must dry before another is applied. All the colors are mixed with animal glue and ox bile to keep them bright. Shading is then done to produce better pictorial effects. Details and facial features are added at the end. The painting is finished and ceremoniously consecrated when the eyes of the main figure are painted. This is done only after a ritual held on a fixed day. After that the canva is removed from the frame and mounted on a piece of brocaded silk. The wooden sticks are attached to the top and bottom of the silk. After a dust cover of gossamer silk is attached, the thangka is ready to be hung,

To paint a thangka of a thousand-faced goddess Chenresig takes an artist three months working 10 to 12 hours a day from a monastery. Exactly 1,000 faces and pairs of arms have to be made according to strict rules; the body and head have to be perfectly proportioned with gold paint applied on a pencil outline. Lobsang Lungtok, a monk artist in Sengeshong who created such a painting of Chenresig told the New York Times, “There are rules, he said, that have been handed down from one Tibetan painter to another through the centuries: The head and body must be perfectly proportioned; the gold paint goes on after the pencil outline; this particular deity has a thousand faces and a thousand arms — no more, no less.[Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, March 29, 2009]

Thangka Artists and Their Training

As an important Tibetan painting form, Thangka with a huge variety of styles, involves mastery of many demanding techniques: mastery in sketching the illustrations and numerous deities according to formal iconography rules laid down by generations of Tibetan masters; learning to grind and apply the paints, which are made from natural stone pigments; and learning to prepare and apply details in pure gold. From the canvas preparation and drawing of the subject, through to mixing and applying colors, decorating with gold, and mounting the finished work in brocade, the creation of a thangka painting involves skill and care at each stage and displays meticulous detail and exquisite artisanship. [Source: “Spiritual Buddhist Art” by Master Locho and Sarika Singh, Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

Therefore, the process of learning to paint thangkas is rigorous. In the first three years, students learn to sketch the Tibetan Buddhist deities using precise grids dictated by scripture. The two years following are devoted to the techniques of grinding and applying the mineral colors and pure gold used in the paintings. In the sixth year, students study in detail the religious texts and scriptures used for the subject matter of their work. To become an accomplished thangka painter, at least ten years training is required under the constant supervision of a master. After the training process, students still need five to ten years to become experts in the field. Most importantly, Tibetan Thangka painting requires extended concentration, attention to detail, and knowledge of Buddhist philosophy, and must be carried out in a peaceful environment.

Mark Stevenson, a senior lecturer in Asian studies at Victoria University in Melbourne, Australia, told the New York Times, “Painting thangkas is simply one component of an array of artistic skills among monks. Every monk has a need for artistic talent, he said. They make and assemble tormas, which are offering cakes. Many may have to work on mandalas as well. This is part of being a monk. Every monk needs some manual skill dexterity in designing ritual objects. The art tradition here suffered a break from 1958 to 1978, when Chinese authorities shut down the monasteries, first during the suppression of a rebellion, then during the Cultural Revolution. Monks were persecuted. Shawu Tsering, for example, was forced to wear a dunce’s cap.

Skilled thangka and mural painters are valued across Tibet, with artists sometimes traveling thousands of miles to do commissions for prominent monasteries. Many monasteries and temples were destroyed or sacked during the Cultural Revolution, and those that have begun rebuilding are in need of painters.

Regong Art Recognized by UNESCO

Regong (Rebgong, Rebkong) arts was inscribed in 2009 on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. According to UNESCO: In monasteries and villages along the Longwu River basin in Qinghai Province in western China, Buddhist monks and folk artists of the Tibetan and Tu ethnicity carry on the plastic arts of painting ''thangka'' and murals, crafting patchwork ''barbola'' and sculpting known collectively as the Regong arts. Their influence extends to nearby provinces and beyond to South-East Asian countries.

Thangka, the art of painting religious scrolls used to venerate Buddha, uses a special brush to apply natural dyes to cloth prepared with patterns sketched in charcoal; barbola employs plant and animal forms cut from silk fabric to create soft relief art for veils and column ornaments; and wood, clay, stone or brick Regong sculpture decorates rafters, wall panels, tea tables and cabinets in both temples and homes.

The technique is mainly passed from fathers to children or from masters to apprentices strictly following ancient Buddhist painting books that provide instruction on line and figure drawing, colour matching and pattern design. Characterized by a distinctively Tibetan Buddhist religion style and unique regional features, the Regong arts embody the spiritual history and traditional culture of the region and remain an integral part of the artistic life of people there today

Regong Thangka Artists

Monasteries in the Regong area in northeastern Qinghai Province are famous for producing thangkas with vibrant colors and fine lines. One of the most well-respected thangka painters, a monk named Shawu Tsering, works in Regong Describing his skill, Stevenson told the New York Times, “watching him paint is remarkable, as if the lines were already there, and he was just moving his hand to bring them forward. It was just so effortless, and the skill and memory were there to allow him to do that.” During the Cultural Revolution Shawu Tsering was forced to wear a dunce cap.

Sengeshong in Qinghai Province is an most important centers of the Regong style of thangka painting. In 1999, artists in the area finished the 675-yard-long Great Thangka, which Guinness World Records certified as the biggest thangka in the world. Of the monks in the two monasteries in Sengeshong, about 60 can paint with some skill, said Lobsang, a compact, cheerful, Red Bull-drinking man who entered the monastery at age 7 and began studying thangka painting seven years later. “There are only a few good ones, and a lot of ordinary ones,” he said of the painters.

Lobsang’s chamber is plush compared to rooms at other Tibetan monasteries. The carpeted living area has a central stove and a framed portrait of the Dalai Lama, the exiled spiritual leader of the Tibetans. There is a photograph of Lobsang standing in his red robes in front of the Shanghai skyline; he lived for five years in Shanghai and Beijing painting thangkas for a businessman.

In warm weather, Lobsang sits in his front yard with a brush in hand, working 10 to 12 hours a day. A safe in the rear room contains some of Lobsang’s more expensive thangkas. The front wall of the foyer has wide glass windows, and it is in this sun-drenched space that Lobsang paints during the winter. Lobsang also teaches thangka painting to others, some of them lay people from nearby villages. We want them to transmit Buddhism, he said. We want them to teach people that the gods are kind.

Artists from Rebkong create works commissioned by other monasteries all over the Tibetan world and recently have produced works for Chinese and foreign collectors. In recent years, thangkas have gained a following among some ethnic Han Chinese, and individual collectors from Chinese cities and foreign countries have driven up the prices. A typical thangka made over three months by a skilled artist sells for about $530, a fortune for most Tibetans. That’s meant the painters of Rebkong are wealthy compared to other groups in Tibetan society.

Famous Thangka

“Imperial Embroidered Silk Thangka” (1402-24) is the most expensive Chinese painting ever sold at auction as of 2020. It was sold for US$44 million at Christie’s in Hong Kong in November 2014. The ornate Tibetan silk thangka is remarkably well-preserved for an object of this age. Because thangkas are painted on a fabric such as cotton or silk they are delicate and it unusual for one to survive a long time in pristine condition. “Imperial Embroidered Silk Thangka”, according to thecollector.com, is a woven thangka from the early Ming dynasty when such articles were sent to Tibetan monasteries and religious and secular leaders as diplomatic gifts. It shows the fierce deity Rakta Yamari, embracing his Vajravetali and standing victoriously atop the body of Yama, the Lord of Death. These figures are surrounded by numerous symbols ic and aesthetic details, all delicately embroidered with the utmost skill.[Source: Mia Forbes thecollector.com, January 2, 2021]

Buddha Amoghasiddhi Attended by Bodhisattvas is a 68.-x-54-centimeter cloth thangka from Tibet dated to the early 13th century. Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts from The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “In Buddhist monasteries, thangkas are often used to focus meditation. This thanka depicts the transcendent Amoghasiddhi, one of the five cosmic Buddhas. Each of these Buddhas has a particular gesture, color, and vehicle and is associated with one of the five directions: north, south, east, west, and straight up. Amoghasiddhi sits in his northern paradise; his gesture allays fear, his color is green, and his vehicle for traveling through the cosmos is Garuda. A Garuda appears on both sides of the throne. He sits in the cross-legged yogic position in front of a large striped bolster and wears lavish jewelry, which symbolizes his spiritual perfection. The soles of his feet and palms of his hands are henna-colored, an ancient form of aristocratic adornment. Two bodhisattvas in tribhanga poses flank him, while above him are smaller bodhisattvas seated in rows who also attend his sermon. The relative sizes of the figures in this crowded scene reflect the degree of their spiritual perfection, and the entire entourage is arranged symmetrically around the central figure of Amoghasiddhi. Five forms of the goddess Tara, the protector and guide of Buddhist pilgrims , are shown seated in a row at the bottom, each a different color and with varying numbers of arms. In the lower right corner is a monk seated before an offering stand. He may have officiated at the ceremony consecrating the set of thankas portraying the five cosmic Buddhas to which this painting belonged.” [Source: Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts, The Art of South, and Southeast Asia, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York]

Thangka of Yama, the God of Death is a 183.8-x-118.4-centimeter cloth mandala from Tibet dated to the mid 17th century to early 18th century. “This powerful painting, over six feet tall, was part of a large set representing the ferocious protectors of Buddhism. Yama is the Indian god of death who, in the corpulent form of a buffalo-headed demon, protects against outer perils such as storms, pestilence, murder, or attacks by wild ani- mals. When he appears with an ogre face, as he does here, Yama guards against the inner demons of emotional addictions such as lust and hate. He carries a chopper (katrika) which he uses to eradicate these demons once the devotee has recognized and overcome them. Yama holds a skull cup in the other hand, filled with the blood of these vanquished evils. He wears a tiger-skin loincloth and a garland of human skulls as he tramples on an agonized being who symbolizes ignorance. He is surrounded by stylized flames and is supported by a black lotus petal floating in seas of blood. On each side of the painting, lightning bolts flash out of clouds, and four small, wrathful buffalo-headed Yamas dance and grimace in the flames. Two serene seated monks holding books flank a fifth small dark- blue image of the ogre-faced Yama at the top of the painting.

Portrait of Jnanatapa Surrounded by Lamas and Mahasiddhas is a 68.6-x-54.6-centimeter cloth thangka from Riwoche monastery in eastern Tibet dated to the 14th century.“The large figure at the center of this cloth painting is a great Indian practitioner of Esoteric Buddhism called Jnanatapa. His large, unfocused eyes indicate that he is in an ecstatic trance. He wears a distinctive golden helmet with a pleated fringe, a large amount of delicately made jewelry, and an apron of carved bone over his red lion cloth. In his right hand is a horn and in the left a golden casket surmounted by a lion. “The palms of his hands and soles of his feet are hennaed in brilliant red, an ancient aristocratic sign of beauty often used in the portrayal of deities and spiritually evolved beings, including abbots. A small golden halo encircles his head with an outer rim of red, yellow, and blue bands symbolizing wisdom and protection. A pair of lions guards the double-lotus throne with jeweled decoration. Behind his throne, vertical shapes with pointed and hooked tops symbolize mountains. Onpo Rinpoche, the founder of Riwoche monastery, for which this painting was made, was believed to be an incar- nation of Jnanatapa. Directly over Jnanatapa’s head is a portrait of a Buddha with his consort. Both were Jnanatapa’s spiritual masters. To each side are three seated figures of abbots. The four central ones are the first abbots of Taklung monastery. The one to the far left is the teacher of its first abbot and the one to the far right, the second abbot of Riwoche. The eight figures along the sides of the lower half of the painting are famous mahasiddhas (great practitioners) of Esoteric Buddhism whose revelations included nontraditional means to achieve spiritual perfection. Their knowledge was kept secret to all but their most spiritually evolved student monks and was passed directly from teacher to adept from generation to generation.”

Giant Thangkas

Terris Temple and Leslie Nguyen wrote in in asianart.com: Each great monastery in Tibet once possessed giant silk applique hangings for public display and worship. These often huge banners comprise some of Tibet's greatest art treasures because of their spiritual significance, size and intricate design. Some survived the cultural revolution - most did not. The giant banners of Tsurphu monastery in central Tibet - traditional seat of the Karmapas - were both destroyed during this time. Between 1992 and 1994, the making of a 23x35 metre silk/brocade applique banner of Sakyamuni was undertaken. The first ceremonial display of this image took place in May 1994. [Source: “Giant Thangkas of Tsurphu Monastery” by Terris Temple and Leslie Nguyen, December 5, 1995, asianart.com/^]

“Tsurphu monastery dates back to 1187. It is situated in a valley two hours north-west of Lhasa. The creation of huge images is traditional throughout Tibet. They are referred to as "gossku." (pronounced Ki-gu) in Tibetan, literally means "Satin-image". These hangings are, in fact, constructed using a range of heavy brocades, silks and satins sewn them together in the applique technique. The intricate linework is translated using a technique similar to that found in Tibetan tent design, typical of this culturally nomadic people. The Karmapas, in particular, were renowned for their elaborate tent settlements.” /^\

The giant thangka at Tsurphu is 23x35 meters in size. It “features nine figures: Sakyamuni Buddha in the centre (9 meters high); Manjusri and Maitreya Bodhisattvas flanking him (7 meters high); the Primordial Buddha at the top centre and a fierce wrathful protector at the bottom centre. At each corner of the image sits a great Lama of the Karmapa lineage. Symbolic beings and animals support the Buddha's throne; clouds and rainbows illuminate the sky above; peacocks and gazelles graze peacefully before the lamas below. Yaks, asses, white-lipped deer, antelopes and the bluehorned sheep all have a place in the image.

Over 1500 metres of silks and brocades were used to make the Tsurphu gossku. Seventy shades of colour were chosen and a large part of this palette was specifically dyed to meet the requirement of a Karma Gadri design which is noted for its use of pastel shades. Additional materials for finishing the thangka include: backing cloth (200 meters), a protective cover (1100 meters), a brocade border (90 meters and a 24 meter leather bag for storage. For ceremonial purposes, a 24 metre canopy to be positioned above the gossku was made, banners, umbrella and 140 metres of multi-coloured traditional streamers were all required and made for the unveiling event.

Making and Unfurling a Giant Thangka

Terris Temple and Leslie Nguyen wrote in in asianart.com: “Creating a large scale image, however, demanded quite a different approach; notably that of an important workforce of sewers to prepare and assemble large pieces of fabrics together. The White Conch factory, based in Lhasa, makes an array of Tibetan handicrafts ranging from huge elaborate festival tents to traditional opera costumes and temple hangings. Seventy odd workers there was involved in the making of the huge religious image. [Source: “Giant Thangkas of Tsurphu Monastery” by Terris Temple and Leslie Nguyen, December 5, 1995, asianart.com/^]

“The six main sewers who spent eight months diligently cutting and sewing silks together by both machine and hand, were all women with over 20 years sewing experience in this setting. Their efforts were co-ordinated by one Tibetan master tailor who, together with the artists, translated the giant drawing, meticulously measured and inked according to iconographical standards, into silken applique forms. The entire project took the artists a total of two years to complete, from its inception in 1992. The last 4 months were spent making the small scale replica of the thangka for presenting to the main patron of this project. /^\

“The month of final assembling work began outside, in the factory courtyard; but as the image quickly grew larger, a gymnasium in Lhasa became the workspace. This allowed half of the thangka to be unrolled and viewed. Before the finished image was delivered to the monastery, certain preparations were made for it to be faithfully consecrated. The sacred syllables "OM", "AH", "HUNG" were cut out in fabric and sewn behind each figure, traditionally placed at their body, speech and mind centres. Also, a fragment of the 400-year old previous Tsurphu gossku, a Bodhisattva head, was placed behind the Buddha's heart as a relic. The finished work was brought to Tsurphu and was consecrated that same day by H.H. Karmapa. /^\

“The ceremonial hanging of the Tsurphu gossku takes place each year on the 12th day of the Tibetan 4th lunar month. This date is the important religious event of "Saga Dawa" which marks the Buddha's birth and enlightenment. In the early morning, the huge thangka is carried from inside the main temple, where it is kept, through the monastery courtyard, across the river and up the facing hill to the top of the steep inclined wall on which it is unfurled. This physically demanding preliminary requires the effort of at least 70 monks. The image is then unrolled and once its protective veil is raised, is visible for about 4 hours. During this time formal ritual offerings are performed and prayers are recited by monks below. This is followed by streams of pilgrims of all generations, presenting themselves before the giant thangka to make their devotional offerings (through the giving of silken scarves and making prostrations) whilst receiving its great blessing. From his balcony at the temple, the Karmapa witnesses the ceremony and crowded scenes below. Before the image is carefully rolled up and carried away for another year, the lines of pilgrims move away from it, across the landscape, towards the temple courtyard, where they wait to pay their respects and make offerings to H.H. Karmapa and receive his blessings.” /^\

Thangka Schools

There different schools of thangka paintings, each with their own style: 1) Karzhi School is known for its painting and sculpture styles. It is said this school follows the painting style that had been used by Karma Mikye Dorje in the Figure Measurement. Karma Mikye Dorje was known for painting calm and kind-hearted figures. 2) ChenZher School was founded by ChenZher ChanMou of KhongKarLdo, Tibet and influenced by, and still uses, the ManThangPa painting style. [Source: chinaculture.org, Chinadaily.com.cn, Ministry of Culture, P.R.China]

3) Mansale School was founded by Qiangpa-Quyang Gyel-tshap. The school's painting style is close to the ManNiang School, and characterized by of bold lines, powerful faces, tall figures, dense colors, and fine painting techniques. 4) Karlri School was founded by the Living Buddha LanMuKar ZhaXi, who combined measurement techniques of Tibetan painting style with the coloring and arrangement of Chinese painting. This school is known for its large pictures and various contents. Figures usually have pleasant and pretty faces with implicit smiles.

5) The JeJuBi School was founded by Karma Quyhang Dorje, who absorbed the painting style of Kashmir and combined it with Tibetan painting. 6) The Manlu School is the collective name of the ManNiang and Mansale schools. 7) The DenLu School follows the painting style of scholars like ChiJar andManThang CharKar, who are known for art books like Figure Measurement Favonian Beads. 8) The ShiGamPa School is also called the Nepal School because of influence from the Nepalese painting style.

9) The Deri School combines the painting style of the Karlri and ManThangPa schools. The school is recognized for sculpture, expression, and connotation of the people painted. 10) ManNiang School was founded by ManlaThongZhu in the 14th century. It is oldest still-functioning painting school in Tibet. Painters in this school almost always paint slim and graceful figure and lifelike expressionsm either smiling or angry, decked in magnificent, fine-colored clothes.

Image Sources: University of Purdue, Kalachakranet.org, CNTO;

Text Sources: 1) “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China”, edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K.Hall & Company, 1994); 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China ethnic-china.com *\; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2022