TIBETAN LANGUAGE

Tibetan in Chinese characters The Tibetan language belongs to the Tibetan language branch of the Tibetan-Burmese language group in the Sino-Tibetan family of languages, a classification that also includes Chinese. Tibetan, often implicitly meaning Standard Tibetan, is an official language of the Tibet Autonomous Region. It is monosyllabic, with five vowels, 26 consonants and no consonant clusters. Maxims and proverbs are very popular among the Tibetans. They use many metaphors and symbols, which are lively and full of meaning. [Source: Rebecca R. French, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

Tibetan is also known as “Bodish.” There are many dialects and regional tongues spoken throughout the Tibetan plateau, the Himalayas, and parts of South Asia. Some are quite different from one another. Tibetans from some regions have difficulty understanding Tibetans from other regions that speak a different dialect. There are two Tibetan languages — Central Tibetan and Western Tibetan — and three main dialects — 1) Wei Tibetan (Weizang, U-Tsang) , 2) Kang (,Kham) and 3) Amdo. The For political reasons, the dialects of central Tibet (including Lhasa), Kham, and Amdo in China are considered dialects of a single Tibetan language, while Dzongkha, Sikkimese, Sherpa, and Ladakhi are generally considered to be separate languages, although their speakers may to be ethnically Tibetan. The standard form of written Tibetan is based on Classical Tibetan and is highly conservative. However, this does not reflect linguistic reality: Dzongkha and Sherpa, for example, are closer to Lhasa Tibetan than Khams or Amdo are.

The Tibetan languages are spoken by approximately 8 million people. Tibetan is also spoken by groups of ethnic minorities in Tibet who have lived in close proximity to Tibetans for centuries, but nevertheless retain their own languages and cultures. Although some of the Qiangic peoples of Kham are classified by the People's Republic of China as ethnic Tibetans, Qiangic languages are not Tibetan, but rather form their own branch of the Tibeto-Burman language family. Classical Tibetan was not a tonal language, but some varieties such as Central and Khams Tibetan have developed tone. (Amdo and Ladakhi/Balti are without tone.) Tibetan morphology can generally be described as agglutinative, although Classical Tibetan was largely analytic.

See Separate Articles: TIBETAN PEOPLE: HISTORY, POPULATION, PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN CHARACTER, PERSONALITY, STEREOTYPES AND MYTHS factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN ETIQUETTE AND CUSTOMS factsanddetails.com; MINORITIES IN TIBET AND TIBETAN-RELATED GROUPS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Lonely Planet Tibetan Phrasebook & Dictionary” by Sandup Tsering Amazon.com; “Learning Practical Tibetan” by Andrew Bloomfield and Yanki Tshering Amazon.com; “The Sino-Tibetan Languages” by Graham Thurgood and Randy J. LaPolla Amazon.com; “A More Inclusive Sino Tibetan Language Family: Evidence of a Common Ancestor to the Sino Tibetan, Koreanic, and Japonic Languages” by Joshua Chen Amazon.com Tibetan Life and Customs: “A Hundred Customs and Traditions of Tibetan People” by Sagong Wangdu and Tenzin Tsepak Amazon.com; Magic and Mystery in Tibet: Discovering the Spiritual Beliefs, Traditions and Customs of the Tibetan Buddhist Lamas” by Alexandra David-Neel and A. D'Arsonval (1931) Amazon.com;“Tibetan Life And Culture” by Eleanor Olson Amazon.com

Written Tibetan

Tibetan is written in an alphabetic system with noun declension and verb conjugation inflections based on Indic languages, as opposed to an ideographic character system. Tibetan script was created in the early 7th century from Sanskrit, the classical language of India and the liturgical language of Hinduism and Buddhism. Written Tibetan has four vowels and 30 consonants and is written from left to right. It is a liturgical language and a major regional literary language, particularly for its use in Buddhist literature. It is still used in everyday life. Shop signs and roads signs in Tibet are often written in both Chinese and Tibetan, with Chinese first of course.

Written Tibetan was adapted from a northern Indian script under Tibet’s first historical king, King Songstem Gampo, in A.D. 630. The task is said to have been completed by a monk named Tonmu Sambhota. The northern India script in turn was derived from Sanskrit. Written Tibet has 30 letters and looks sort of like Sanskrit or Indian writing. Unlike Japanese or Korean, it doesn’t have any Chinese characters in it. Tibetan, Uighur, Zhuang and Mongolian are official minority languages that appear on Chinese banknotes.

Tibetan scripts were created during the period of Songtsen Gampo (617-650), For much of Tibet’s history Tibetan language study was conducted in monasteries and education and the teaching of written Tibetan was mainly confined to monks and members of the upper classes. Only a few people had the opportunity to study and use Tibetan written language, which was mainly used for government documents, legal documents and regulations, and more often than not, used by religious people to practice and reflect the basic contents and ideology of Buddhism and Bon religion.

Tibetan Grammar and Pronunciation

Tibet in 1938 before

the Chinese took it over Tibetan uses conjugated verbs and tenses, complicated prepositions and subject-object-verb word order. It has no articles and possesses an entirely different set of nouns, adjectives and verbs that are reserved only for addressing kings and high ranking monks. Tibetan is tonal but the tones are far less important in terms of conveying word meaning than is the case with Chinese.

Tibetan is classified as an ergative-absolutive language. Nouns are generally unmarked for grammatical number but are marked for case. Adjectives are never marked and appear after the noun. Demonstratives also come after the noun but these are marked for number. Verbs are possibly the most complicated part of Tibetan grammar in terms of morphology. The dialect described here is the colloquial language of Central Tibet, especially Lhasa and the surrounding area, but the spelling used reflects classical Tibetan, not the colloquial pronunciation.

Word Order: Simple Tibetan sentences are constructed as follows: Subject — Object — Verb. The verb is always last. Verb Tenses: Tibetan verbs are composed of two parts: the root, which carries the meaning of the verb, and the ending, which indicates the tense (past, present or future). The simplest and most common verb form, consisting of the root plus the ending-ge ray, can be used for the present and future tenses. The root is strongly accented in speech. In order to form the past tense, substitute the ending -song. Only the verb roots are given in this glossary and please remember to add the appropriate endings.

Pronunciation: The vowel "a" must be pronounced like the "a" in father-soft and long, unless it appears as ay, in which cast it is pronounced as in say or day. Note that words beginning with either b or p, d or t and g or k are pronounced halfway between the normal pronunciation of these constant pairs (e.g., b or p), and they are aspirated, like words starting with an h. A slash through a letter indicates the neural vowel sound uh.

Greetings and Friendly and Polite Tibetan Words

The following are some useful Tibetan words that you might use during a travel in Tibet: English — Pronunciation of Tibetan: [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

Hello — tashi dele

Goodbye ( when staying) — Kale Phe

Goodbye ( when leaving) — kale shoo

Good luck — Tashi delek

Good morning — Shokpa delek

Good evening — Gongmo delek

Good day — Nyinmo delek

See you later—Jeh yong

See you tonight—To-gong jeh yong.

See you tomorrow—Sahng-nyi jeh yong.

Goodnight—Sim-jah nahng-go

How are you — Kherang kusug depo yin pey

I'm fine—La yin. Ngah snug-po de-bo yin.

Nice to meet you — Kherang jelwa hajang gapo chong

Thank you — thoo jaychay

Yes/ Ok — Ong\yao

Sorry — Gong ta

I don't understand — ha ko ma song

I understand — ha ko song

What's your name?—Kerang gi tsenla kare ray?

My name is ... - and yours?—ngai ming-la ... sa, a- ni kerang-gitsenla kare ray?

Where are you from?—Kerang loong-pa ka-ne yin?

Please sit down—Shoo-ro-nahng.

Where are you going?—Keh-rahng kah-bah phe-geh?

Is it OK to take a photo?—Par gyabna digiy-rebay?

Useful Tibetan Words

The following are some useful Tibetan words that you might use during a travel in Tibet: English — Pronunciation of Tibetan: [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org tibettravel.org, June 3, 2014 ]

Sorry — Gong ta

I don't understand — ha ko ma song

I understand — ha ko song

How much? — Ka tso re?

I feel uncomfortable — De po min duk.

I catch a cold. — Nga champa gyabduk.

Stomach ache — Doecok nagyi duk

Headache — Go nakyi duk

Have a cough — Lo gyapkyi.

Toothache — So nagyi

Feel cold — Kyakyi duk.

Have a fever — Tsawar bar duk

Have diarrhea — Drocok shekyi duk

Get hurt — Nakyi duk

Public services — mimang shapshu

Where is the nearest hospital? — Taknyishoe kyi menkang ghapar yore?

What would you like to eat — Kherang ga rey choe doe duk

Is there any supermarket or department store? — Di la tsong kang yo repe?

Hotel — donkang.

Restaurant — Zah kang yore pe?

Bank — Ngul kang.

Police station — nyenkang

Bus station — Lang khor puptsuk

Railway station — Mikhor puptsuk

Post office — Yigsam lekong

Tibet Tourism Bureau — Bhoekyi yoelkor lekong

You — Kye rang

I — nga

We — ngatso

He/she —Kye rang

Tibetan Swear Words and Expressions

Phai shaa za mkhan — Eater of father's flesh (strong insult in Tibetan)

Likpa — Dick

Tuwo — Pussy

Likpasaa — Suck my dick

[Source: myinsults.com]

Modernization of the Written Tibetan Language

Tibet in 1938 before

the Chinese took it over

Since the People's Republic of China (modern China) in 1949, the uses of written Tibetan language has expanded. In Tibet and the four provinces (Sichuan,Yunnan, Qinghai and Gansu), where many ethnic Tibetans live, Tibetan language has entered into the curriculum at varying degrees in universities, secondary technical schools, middle schools and primary schools at all levels. At some schools written Tibetan is widely taught. At others minimally so. In any case, China should be given some credit for helping Tibetan written language study to expand from the confines of the monasteries and become more widely used among ordinary Tibetans.

The approach of Chinese schools to Tibetan language study is very different from the traditional study methods used in monasteries. Since the 1980s, special institutes for Tibetan language have been established from provincial to township level in Tibet and the four Tibetan inhabited provinces. Staff at these institutions have worked on translations in order to expand the literature and function of Tibetan language and created a number of terminologies in natural and social sciences. These new terminologies have been classified into different categories and compiled into cross-language dictionaries, including a Tibetan-Chinese Dictionary, a Han-Tibetan Dictionary, and a Tibetan-Chinese-English Dictionary.

In addition to making Tibetan translations of some well-known literary works, such as Water Margin, Journey to the West, The Story of the Stone, Arabian Nights, The Making of Hero, and The Old Man and the Sea, translators have produced thousands of contemporary books on politics, economics, technology, movies and Tele-scripts in Tibetan. In comparison with the past, the number of Tibetan newspapers and periodicals has dramatically increased. Along with the advancement of broadcasting in Tibetan inhabited areas, a number of Tibetan programs have put air, such as news, science programs, the stories of King Gesar, songs and comic dialogue. These not only cover the Tibetan inhabited areas of China, but also broadcast to other countries such as Nepal and India where many overseas Tibetans can watch. Government-sanctioned Tibetan language input software, some Tibetan language databases, websites in Tibetan language and blogs have appeared. In Lhasa, a full screen Tibetan interface and an easy-input Tibetan language for cell phones are widely used.

Tibetan Versus Chinese Languages

Most Chinese can't speak Tibetan but most Tibetans can speak at least a little Chinese although degrees of fluency vary a great deal with most speaking only basic survival Chinese. Some young Tibetans speak mostly Chinese when they are outside the home. From 1947 to 1987 the official language of Tibet was Chinese. In 1987 Tibetan was named the official language.

Robert A. F. Thurman wrote: “Linguistically, the Tibetan language differs from the Chinese. Formerly, Tibetan was considered a member of the "Tibeto-Burman" language group, a subgroup assimilated into a "Sino-Tibetan" language family. Chinese speakers cannot understand spoken Tibetan, and Tibetan speakers cannot understand Chinese, nor can they read each other's street signs, newspapers, or other texts. [Source: Robert A. F. Thurman, Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity, Gale Group, Inc., 2005]

It is rare to find a Chinese person, even one who has lived in Tibet for years, who can speak more than basic Tibetan or who has bothered to study Tibetan. Chinese government officials seem particularly adverse to learning the language. Tibetan claims that when they visit government offices they have to speak Chinese or no one will listen to them. Tibetans, on other hand, need to know Chinese if they want to get ahead in a Chinese-dominated society.

In many towns signs in Chinese outnumber those in Tibetan. Many signs have large Chinese characters and smaller Tibetan script. Chinese attempts to translate Tibetan are often woefully lacking. In one town the “Fresh, Fresh” restaurant was given the name “Kill, Kill” and a Beauty Center became the “Leprosy Center.”

Decline of the Teaching of Tibetan and the Decline of the Tibetan Language in Tibet

Chinese has displaced Tibetan as the main teaching medium in schools despite the existence of laws aimed at preserving the languages of minorities. Young Tibetan children used to have most of their classes taught in Tibetan. They began studying Chinese in the third grade. When they reached middle school, Chinese becomes the main language of instruction. An experimental high school where the classes were taught in Tibetan was closed down. In schools that are technically bilingual, the only classes entirely taught in Tibetan were Tibetan language classes. These schools have largely disappeared.

These days many schools in Tibet have no Tibetan instruction at all and children begin learning Chinese in kindergarten. There are no textbooks in Tibetan for subjects like history, mathematics or science and tests have to be written in Chinese. Tsering Woeser, a Tibetan writer and activist in Beijing,, told the New York Times that when she lived” in 2014" in Lhasa, she stayed by a kindergarten that promoted bilingual education. She could hear the children reading aloud and singing songs every day — in Chinese only.

Woeser, who studied Tibetan on her own after years of schooling in Chinese, told the New York Times: “A lot of Tibetan people realize this is a problem, and they know they need to protect their language,” said Ms. Woeser, She and others estimate that the literacy rate in Tibetan among Tibetans in China has fallen well below 20 percent, and continues to decline.The only thing that will stave off the extinction of Tibetan and other minority languages is allowing ethnic regions in China more self-governance, which would create an environment for the languages to be used in government, business and schools, Ms. Woeser said. “This is all a consequence of ethnic minorities not enjoying real autonomy,” she said. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, November 28, 2015]

See Separate Article EDUCATION IN TIBET factsanddetails.com

Pushing Chinese While Arresting those who Push Tibetan

In August 2021, Wang Yang, a top Chinese official said that “all-round efforts” are needed to make sure Tibetans speak and write standard Chinese and share the “cultural symbols and images of the Chinese nation.” He made the remarks before a handpicked audience in front of the Potala Palace in Lhasa at a ceremony marking the 70th anniversary of the Chinese invasion of Tibet, which the Chinese call a “peaceful liberation" Tibetan peasants from an oppressive theocracy and restored Chinese rule over a region under threat from outside powers.[Source: Associated Press, August 19, 2021]

In November 2015, the New York Times published a 10-minute video about Tashi Wangchuk, a Tibetan businessman, that followed him as he travelled to Beijing to advocate for the preservation of his ethnic language. In Tashi’s telling, the poor standards for Tibetan language instruction in his hometown of Yushu (Gyegu in Tibetan), Qinghai Province, and pushing of Mandarin language instead was tantamount to “a systematic slaughter of our culture.” The video opens with an excerpt of China’s constitution: All nationalities have the freedom to use and develop their own spoken and written languages and to preserve or reform their own folkways and customs. [Source: Lucas Niewenhuis, Sup China, May 22, 2018]

“Two months later, Tashi found himself arrested and accused of “inciting separatism,” a charge liberally applied to repress ethnic minorities in China, especially Tibetans andUyghurs in China’s far west. In may 2018, was sentenced to five years in prison. “Tashi told Times journalists that he did not support Tibetan independence and just wanted the Tibetan language to be taught well in schools,” the Times recalls in itsreporting on his sentencing. “He has been criminalized for shedding light on China’s failure to protect the basic human right to education and for taking entirely lawful steps to press for Tibetan language education,” Tenzin Jigdal of the International Tibet Network told the Times. “Tashi plans to appeal. I believe he committed no crime and we do not accept the verdict,” one of Tashi’s defense lawyers told AFP. Tashi is due for release in early 2021, as the sentence starts from the time of his arrest.

Protests in Qinghai Over Efforts to Curb the Tibetan Language

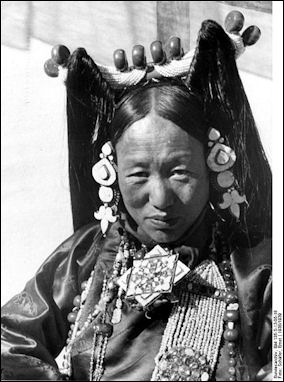

Tibetan woman in 1938 In October 2010, at least 1,000 ethnic Tibetan students in the town on Tongrem (Rebkong) in Qinghai Province protested curbs against the use of the Tibetan language. They marched through the streets, shouting slogans but were left alone by police observors told Reuters. [Source: AFP, Reuters, South China Morning Post, October 22, 2010]

The protests spread to other towns in northwestern China, and attracted not university students but also high school students angry over plans to scrap the two language system and make Chinese the only instruction in school, London-based Free Tibet rights said. Thousands of middle school students had protested in Qinghai province's Malho Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in anger at being forced to study in the Chinese language. About 2,000 students from four schools in the town of Chabcha in Tsolho prefecture marched to the local government building, chanting “We want freedom for the Tibetan language,” the group said. They were later turned back by police and teachers, it said. Students also protested in the town of Dawu in the Golog Tibetan prefecture. Police responded by preventing local residents from going out into the streets, it said.

Local government officials in the areas denied any protests. “We have had no protests here. The students are calm here,” said an official with the Gonghe county government in Tsolho, who identified himself only by his surname Li. Local officials in China face pressure from their seniors to maintain stability and typically deny reports of unrest in their areas.

The protests were sparked by education reforms in Qinghai requiring all subjects to be taught in Mandarin and all textbooks to be printed in Chinese except for Tibetan-language and English classes, Free Tibet said. “The use of Tibetan is being systematically wiped out as part of China's strategy to cement its occupation of Tibet,” Free Tibet said earlier this week. The area was the scene of violent anti-Chinese protests in March 2008 that started in Tibet's capital Lhasa and spread to nearby regions with large Tibetan populations such as Qinghai.

Modern Mandarin-Speaking Tibetans

Describing his Tibetan taxi driver in Xining near the Dalai Lama’s birthplace in Qinghai Province, Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker, “Jigme wore green cargo shorts and a black T-shirt with a mug of Guinness silk-screened on the front. He was an enthusiastic travel companion. His father was a traditional Tibetan opera musician who had received two years of schooling before going to work. When his father was growing up, he would walk seven days from his home town to Xining, the provincial capital. Jigme now makes the same trip three or four times a day in his Volkswagen Santana. A Hollywood buff, he was eager to talk about his favorites: “King Kong,” “Lord of the Rings,” Mr. Bean. Most of all, he said, “I like American cowboys. The way they ride around on horses, with hats, it reminds me a lot of Tibetans.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, October 4, 2010]

“Jigme spoke good Mandarin. The central government has worked hard to promote the use of standard Mandarin in ethnic regions like this, and a banner beside the train station in Xining reminded people to ‘standardize the Language and Script.” Jigme was married to an accountant, and they had a three-year-old daughter. I asked if they planned to enroll her in a school that taught in Chinese or in Tibetan. “My daughter will go to a Chinese school,” Jigme said. “That’s the best idea if she wants to get a job anywhere outside the Tibetan parts of the world.”

When Osnos asked him how the Han Chinese and the Tibetans were getting along, he said, “In some ways, the Communist Party has been good to us. It has fed us and made sure we have a roof over our heads. And, where it does things right, we should acknowledge that.” After a pause, he added, “But Tibetans want their own country. That’s a fact. I graduated from a Chinese school. I can’t read Tibetan.” But even though he didn’t know the town of Takster was the birthplace of the Dalai Lama when he visited the Dalai Lama’s house he asked if he could pray inside the threshold, where he “fell to his knees and press his forehead to the cobblestones.”

Tibetan Names

Many Tibetans go by a single name. Tibetans often change their name after major events, such a visit to an important lama or recovery from a serious illness. Traditionally, Tibetans had given names but no family names. Most of the given names, usually two or four words long, originate from Buddhist works. Hence, many Tibetan people have the same names. For differentiation purposes, Tibetans often add "the old" or "the young," their character, their birthplace, their residence, or their career title before their name. [Source: chinaculture.org, Chinadaily.com.cn, Ministry of Culture, P.R.China]

As a rule, a Tibetan goes only by his given name and not family name, and the name generally tells the sex. As the names are mostly taken from Buddhist scripture, namesakes are common, and differentiation is made by adding "senior," "junior" or the outstanding features of the person or by mentioning the birthplace, residence or profession before the names. Nobles and Lamas often add the names of their houses, official ranks or honorific titles before their names. [Source: China.org china.org |]

Originally, the Tibetans didn’t have family names and they only had names which usually consisted of four words, such as Zha Xi Duo Jie. In Tibetan matriarchal society, they were given names containing one word of their mother’s name. For example the mother Da Lao Ga Mu named her son Da Chi. Family names appeared with the coming of social classes. The high class people adopted family name as their first name and thus, family name appeared. Later, Songtsen Gampo (617-650), the founder of the Lhasa-based kingdom in Tibet and gave lands and territories to his allies. These allies adopted their lands’ names as their first names. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

Tibetans usually give their children names embodying their own wishes or blessings towards them. In addition, Tibetan names often say something on the earth, or the date of one’s birthday. Today, most of The Tibetan names still consist of four words, but for the convenience, they are usually shortened as two words, the first two words or the last two, or the first and the third, but no Tibetans use a connection of the second and the fourth words as their shortened names. Some Tibetan names only consist of two words or even one word only, for example Ga.

Tibetan Naming Culture

Many Tibetans seek out a lama (a monk regarded as a living Buddha) to name their child. Traditionally, rich people would take their children to a lama with some presents and ask for a name for their child and the lama said some blessing words to the child and then give him a name after a small ceremony. These days even ordinary Tibetans can afford to have this done. Most of the names given by the lama and mainly come from Buddhist scriptures, including some words symbolizing happiness or luck. For example, there are names such as Tashi Phentso, Jime Tsering, and so on. [Source: chinaculture.org, Chinadaily.com.cn, Ministry of Culture, P.R.China]

If a male becomes a monk, then no matter how old he is, he is given a new religious name and his old name is no longer used . Usually, high-ranking lamas give part of their name to lower-ranking monks when making a new name for them in the monasteries. For example a lama named Jiang Bai Ping Cuo may give religious names Jiang Bai Duo Ji or Jiang Bai Wang Dui to ordinary monks in his monastery.

According to the Chinese government: In the first half of the 20th century, Tibet was still a feudal-serf society in which names marked social status. At that time, only the nobles or living Buddhas, about five percent of the Tibetan population, had family names, while Tibetan civilians could only share common names. After the Chinese completed taking over Tibet in 1959, the nobles lost their manors and their children began to use civilian names. Now only the old generation of Tibetans still bears manor titles in their names.

With the old generation of Tibetan nobles passing away, the traditional family names indicating their noble identities are fading out. For instance, Ngapoi and Lhalu (both family names and manor titles) as well as Pagbalha and Comoinling (both family names and titles for living Buddhas) are vanishing.

Because lamas christen children with common names or commonly used words indicating kindness, prosperity, or goodness many Tibetan have the same names. Many Tibetans favor "Zhaxi," meaning prosperity; as a result, there are thousands of young men named Zhaxi in Tibet. These namesakes also bring troubles for schools and universities, especially during the middle school and high school examinations each year. Now, a growing numbers of Tibetans are seeking unique names to display their uniqueness, such as adding their birthplace before their name.

Image Sources: Purdue University, China National Tourist Office, Nolls China website , Johomap, Tibetan Government in Exile

Text Sources: 1) “ Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China”, edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K.Hall & Company, 1994); 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China ethnic-china.com *\; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2022