TIBETAN SOCIETY

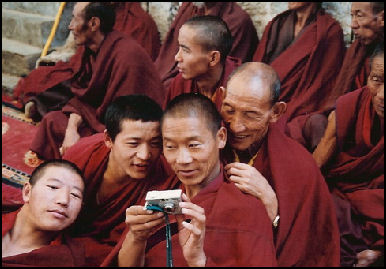

Monks with a digital camera

Rebecca R. French wrote: “The web of bilateral kin associated with households was the basis for local social organization. Villages had headmen and head irrigators who coordinated agricultural projects. Titleholders coordinated estates into social units. Monasteries and nunneries operated as independent social units within communities.[Source: Rebecca R. French, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

Villages typically have a headmen. They also typically have a community association called a "skyid sdug" that coordinates prayers, dances, singing, religious festivals, marriages, pilgrimage, funerals, commercial ventures and other activities.

Tibetan society has traditionally been very resistant to change. After the Communists took over Tibet, The aristocracy and titles were abolished and China became the state but most farmers continued to work the land as they have for centuries. Collective farming never really worked in Tibet. Nomads were especially resistant to it. But today things are changing very quickly as the influence of the Chinese grows on material and day to day levels.

See Separate Articles: TIBETAN ETIQUETTE AND CUSTOMS factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN FAMILIES, MEN, WOMEN AND CHILDREN factsanddetails.com;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Eat the Buddha: Life and Death in a Tibetan Town” by Barbara Demick, Cassandra Campbell, et al. Amazon.com; “Yak Butter & Black Tea: A Journey into Tibet” by Wade Brackenbury Amazon.com; “Life and Marriage in Skya rgya, a Tibetan Village” by Blo Brtan Rdo Rje and Charles Kevin Stuart Amazon.com; “Social Structuration in Tibetan Society: Education, Society, and Spirituality” by Jia Luo Amazon.com; “Gompas in Traditional Tibetan Society” by M.N. Rajesh Amazon.com; “A Hundred Customs and Traditions of Tibetan People” by Sagong Wangdu and Tenzin Tsepak Amazon.com; Magic and Mystery in Tibet: Discovering the Spiritual Beliefs, Traditions and Customs of the Tibetan Buddhist Lamas” by Alexandra David-Neel and A. D'Arsonval (1931) Amazon.com;“Tibetan Life And Culture” by Eleanor Olson Amazon.com; “Tibetan Buddhist Life” by Don Farber and The Tibet Fund Amazon.com; “Women in Tibet: Past and Present” by Janet Gyatso and Hanna Havnevik Amazon.com; “The Unique Customs and Taboos in Tibet and Their Meanings” by Kokshin Tan Amazon.com; “Customs and Superstitions of Tibetans: by Marion H. Duncan (1964) Amazon.com; “The Tibetan Art of Parenting: From Before Conception Through Early Childhood” by Anne Maiden Brown , Edie Farwell, et al. Amazon.com; “Tibet: Life, Myth and Art” by Michael Willis Amazon.com

Divisions in Tibetan Society

Tibetans have traditionally divided into groups according to geographic origin, occupation, and social status. The plateau was divided into five general regions, each with a distinctive climate: the northern plain, which is almost uninhabited; the southern belt on the Tsangpo River, which is the heart of the agricultural settlements; western Tibet, a mountainous and arid area; the southeast, which has rich temperate and subtropical forests and more rain-fall; and the northeast terrain of rolling grasslands dotted with mountains, famous for its herding. [Source: Rebecca R. French, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

Tibetan society also was traditionally divided into peasants (“rongpa”), nomads (“drokpa”) and monks and nuns (“sangha”), with hierarchal rankings of noblemen, landowners, craftsperson, peasants and slaves. There was also a kind caste system for government officials, monastic businessmen, traders, high lamas, and ordinary monks. Rank and status was often reflected in dress, housing and the speech used to address peers, superiors and inferiors. Untouchable-like groups can be found in Tibet as they can in Japan (the Buraku), Korea (the Paekching) and Burma (Pagoda slaves). The Ragyappa are a group of outcasts in Tibet in charge of getting rid of corpses.

According to the Chinese government: “The strict social caste system was manifested even in the use of language. The Tibetan language has three major forms of expression: the most respectful, the respectful and the everyday speech, to be used respectively to one's superiors, one's peers and one's inferiors. The social distinctions were also reflected in people's dresses, houses, horses and Hadas — silk scarves presented on all social occasions to show respect. In the old days, ceremonies and religious rites were held for weddings, burials or births in the homes of manorial lords. For the serfs, however, these meant nothing but extra services. Women had to give births outside their houses and women serfs had to work only a few days after delivery. Lack of proper medical care and nutrition resulted in a very high infant mortality rate. [Source: China.org china.org |]

many articles TIBETAN LIFE factsanddetails.com TIBETAN PEOPLE factsanddetails.com ; 10TH TO 18TH CENTURY TIBET: FEUDALISM, BUDDHISM, CHINA, MONGOLS factsanddetails.com ; Tibetan Society case.edu

Poverty in Tibet

Tibet is the home of some of China's poorest people. In 1995, the average urban income in Tibet was $133 and the average rural income was $106. Nearly all the beggars in Tibet are Tibetans rather than members of other ethnic groups.

Many Tibetans earn less than $100 a year. Some are nomads who spend their summers herding yaks and their winters begging in Lhasa. Others are children with mated hair that scavenge at the trash dumps outside of Lhasa. In many places people subsist almost entirely on barley dumplings. They are so poor they can’t even afford the most basic fruits and vegetables.

Beggars and pilgrims in patched robes or hand-sewn skins were once common sight in Lhasa but not any longer. Many Chinese government agencies are involved in anti-poverty programs.

Still urban poverty exists. There are monks that spend their days begging and nights sleeping in Internet cafes for $1 a night. One who talked to the Washington Post said on a good day he makes $7; one a bad day, $3, more than a farmer can make.

See Nomads and the Modern World

Begging Pilgrims in Tibet

In Tibet, begging is not seen as something poor people do to get food but rather a sacred activity for pilgrims similar to what the Buddha did when he was went through his holy man stage and was a wandering teacher. manner. Tibet has a long tradition of begging for alms. In the past, two rows of huts were built to give shelter to beggars at the end of Barkor Street in front of the present-day Tibet Hospital. Lines of blind beggars linked together by a rope were led by a dim-sighted beggar, chanting and singing in deep and low voices. Today, monks sometimes sit along the street cross-legged, chanting sutras and begging for alms. In front of each is a long horizontal piece of cloth with quotations from the Buddhist scriptures written on a particular theme. The are also some child beggars and some are pilgrims from other places, who are spinning a prayer wheel and begging for alms. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org tibettravel.org]

Some Tibetan pilgrims travel for months to reach Lhasa to worship at the city’s sacred temples. No matter how rich they are, they do not carry lots of money for their pilgrimage. They beg all the way to their last destination, and do the same when they return home. Even the rich monasteries send monks out to ask for alms.

Some beggars in Tibet are not begging for themselves but for sacred temples, holy mountains and lakes. After begging for tens of years, they spend thousands of yuan to plate the Buddha of Sakyamuni with gold, or throw jewelry valued tens of thousands of yuan into holy lakes. Therefore, Tibetan people never skimp on giving alms to beggars. It is considered meritorious to give alms. But tourists may sometimes find themselves being pestered by the beggars.

Rich and Middle Class in Tibet

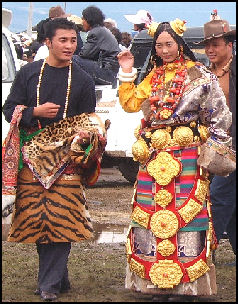

Rich Tibetans with

tiger skin clothes There are a handful of rich Tibetans. Denba Daji, a former horse trader and antiques smuggler, earned a fortune in Gungdon and now owns a company that markets traditional Tibetan medicines, two hotels, 20 percent of a winery in Shandong, and a seaside house in Fujian province. Some of the money he has earned has been put into things like a vocational training school for Tibetan teenagers.

Many Tibetans that are relatively well off are traders. One interviewed by National Geographic buys up rare mushrooms, known as caterpillar fungus, and sell them for large profits to traditional medicine makers. On the Chinese, he said, “Once you realize they are never going to help us you realize that you have to make your own future.”

Animals have traditionally been a sign of wealth in Tibet. Yaks are the most valuable animals. Seven goats or six sheep usually equal one yak. Nomads used to be required to sell certain numbers of animals to government agencies at a certain price. In the 1980s they began selling their yaks and sheep at market prices. Some rich Tibetans display their wealth in the form of clothing made with tiger and snow leopard skins.

Development and economic growth has helped create a Tibetan middle class. Most middle class Tibetans are employed by the government or are entrepreneurs. Many live in Chinese-built concrete apartments. One Tibetan interviewed by the Washington Post said his family was given land and he was given a job as a truck driver by the central government. He lives in a spacious two-story house with his family and has three televisions. His two sons went to university and got government jobs. “We’re very grateful to the party,” he said.

No matter how much money they have, Tibetan have traditionally given some of it to local monasteries or donated some to erect or repair local Buddhist stupas. When the Dalai Lama was told about such people he said the money “would be better spent on schools and health care.”

See Business

Everyday Life in Tibet

In the countryside adults work about 49 hours a week (7 hours a day, 7 days a week). Women often throw their young children in slings and toss them on their back when they perform chores such as butter churning. In the morning men cut firewood and bring anything of value (such as berries or mushrooms) that can be found along the way.

Tibetan filmmaker Losang Gyatso told the Los Angeles Times: The overwhelming majority of Tibetans lead rural, agrarian lives. Quite a large percentage, about 20-25 percent, were nomadic, traditionally. But the nomads have had a very difficult time of it over the past decade. Their pastures were cordoned off and they were forced to sell their animals and move into housing units. It’s been the closing off of a whole way of life, not just a means of earning a living. [Source: Carol J. Williams, Los Angeles Times, June 6, 2013]

Describing daily life in Three Parallel Rivers area on the border of Tibet and Yunnan Province Mark Jenkins wrote in National Geographic: “Grandparents, parents and kids all share the farm house. All have their tasks: the scrawny uncle carrying sacks of corn and sorting horseshoes; the young mother, baby on her back, tending the stove and preparing dinner; the patriarch slowly writing something in scratchy script. The sinewy woman...is the matriarch, She slops the hogs with a kitchen pail, dumping the contents over the railing, then goes outside where she milks the cows and feeds the horses and churns the yak butter.”

“The women of the household are up for hours before dawn, hauling water and wood, milking and feeding the animals. The young mother pours yak butter tea...Her baby in one arm, she is simultaneously breast feeding, loading firewood into the stove, checking the rice, stirring the yak butter tea, tossing potato peels over the railing to the pigs, washing dishes, sorting peppers and talking.”

Tibetan Possessions

In poor rural areas many homes don't even have chairs or tables. People sit barefoot on quilts placed on the floor. Oil lamps are used for lighting. Wooden bins are used for storing grain and salt. Yak butter statutes made from dirt and flour paste protect the house from lightning and evil spirits.

The possessions of a typical family include a butter lamp, nine hoes and cultivators, a basket for winnowing grain, baskets, bags of rice, a ladder for reaching the attic (made from a tree), a clay pot for water, pantry cabinets, three storage chests, three blankets, a treadle-style sewing machine, a pitch fork, butter churn, cooking pots, 11 storage baskets, built-in altar, built-in earthen stove, rice milling machine, battery-operated radio, woodpile, yoke for bulls, four cats, two dogs, many chickens, dart game and candles.

Describing a rudimentary water-generator used in a remote valley in Three Parallel Rivers area on the border of Tibet and Yunnan Province Mark Jenkins wrote in National Geographic: “At nightfall its is pitch-dark and frosty inside the house. A terrific screeching cuts the stillness, The patriarch is turning a metal crank mounted on the wall, winding up a cable. As he locks the crack arm in place, compact fluorescent light bulbs dangling around the house burst to life. The metal cable extends to a creek 400 yards from the farmhouse. There it is attached to a trough carved from a log. Turning the crank pulls the cable which lifts the through, sending a flow of creek water into a large wood cask. Plugged into tthe base of the cask is a blue plastic pipe that carries water down a Chinese-made micro-hydropower generator the size of a five-gallon drum.”

See Tableware, Wooden Bowls Under TIBETAN POSSESSIONS factsanddetails.com

Religion and Everyday Life in Tibet

Life is dominated by religion. Religion is a daily, if not hourly practice. Tibetans spend much of their time in prayer or doing activities, such as spinning prayer wheels and hanging prayer flags, that earn them merit. Tibetan Buddhists also send their sons to monasteries, participate in pilgrimages, do good deeds and present gifts to lamas to earn merit.

Common rituals include rubbing holy stones together and performing the traditional blessing of dipping a finger in milk and flicking it towards the sky (more common in Mongolia than Tibet). Buildings are blessed by a lama who circles it twice and casts handfuls of rice in all directions. As one Tibetan Buddhist explained, "Before you do anything, you have to have the permission of the gods."

According to the BBC: Rituals and simple spiritual practices such as mantras are popular with lay Tibetan Buddhists. They include prostrations, making offerings to statues of Buddhas or bodhisattvas, attending public teachings and ceremonies. Tibetan Buddhism also involves many advanced rituals. These are only possible for those who have reached a sophisticated understanding of spiritual practice. There are also advanced spiritual techniques. These include elaborate visualisations and demanding meditations. It's said that senior Tibetan yoga adepts can achieve much greater control over the body than other human beings, and are able to control their body temperature, heart rate and other normally automatic functions.

See Separate Article TIBETAN BUDDHIST RITUALS, CUSTOMS AND PRAYERS factsanddetails.com

Life in Tibet at 17,000 Feet

Many Tibetans go barefoot even in sub-freezing temperatures. Not surprisingly their feet have thick leathery dark calluses on them. To keep from getting frostbite in severe cold they wrap their feet in woolen rags. To prevent snow blindness men wrap their long braids over their eyes and women smear black soot under their eyes.

The boiling temperature of water is so low that boiling water from a pot doesn't burn when it touches the skin. Vehicles often breakdown because of the elevation and are restarted again after fluid is sucked from the engine with a tube.

Tibetans on the dry Tibetan plateau have little water for washing and have traditionally considered washing to be an unhealthy, harmful practice. As a result many Tibetans are very dirty: their faces and hands are sometimes covered in a layer of greasy yak-butter and dirt, their clothes are caked in dirt and their hair is matted.

When Tibetan nomads do wash, they tend to rinse their faces and hands in yak or goat milk. To protect their skin and beautify themselves some nomad women apply a salve to their face made from boiled milk curds. Some people go through the entire life without ever taking bath.

See Separate Article HEALTH AND DISEASES AT HIGH ALTITUDES factsanddetails.com

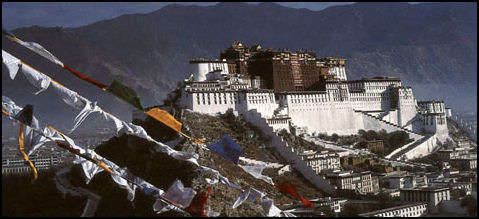

One view of Potala

Urban Life in Tibet

Xinhua reported: As the first beam of morning sunlight hits the tops of the flagpoles in front of Lhasa's Jokhang Temple, Drolma Lhamo begins her daily ritual walk along Barkhor Street. Strolling clockwise along the street, which encircles the temple in the heart of historic Lhasa, has long been a regular religious practice by Tibetan Buddhists. [Source: Xinhua, May 8, 2011]

“For Drolma Lhamo, the street has changed considerably since the 79-year-old first began walking there with her mother as a child. Stone pavement has covered a previously barren earth road, and street lamps now light the street's dark and narrow side alleys. Signs hanging in front of stores are written in a mix of Tibetan, Chinese and English. However, in front of the 1,300-year-old Jokhang Temple, pilgrims are kneeling to the ground and praying in much the same way they did centuries ago.

“Drolma Lhamo was born and raised in a traditional-style courtyard located on one of the 35 labyrinthine lanes leading to Barkhor Street. This area used to be a major residential district in old Lhasa. "When I was a child, the courtyard was larger, but the buildings were also much more shabby, with mud walls and rough wood pillars. There was no electricity and we shared a well in the yard," she recalls."I remember the courtyard was owned by a temple and the families living here rented rooms from them." Today, the three-floor buildings enclosing the courtyard are gleaming with windows framed by black and yellow trim. Some families have grown brightly-colored flowers on the balconies facing the yard.

“In 1994, every home in the courtyard was equipped with electricity and tap water access. Although there used to be just one public bathroom for the entire courtyard, there is now a bathroom on every floor of every building. Many of the courtyards around Barkhor Street have undergone similar renovations since 1979. Last year, the local government decided to restore and rebuild 56 of the most well-known courtyards. However, even these refurbished homes cannot compete with the newly-built modern apartments in the city's younger areas. "Most of my old neighbors have moved out. At least half of the neighbors now are small-business owners and migrant workers," Drolma Lhamo says. She doesn't want to leave the area, even though her children keep asking her about it. "I'm used to the life here. It's really convenient for me to do my ritual walk," she says.”

Modernization of Lhasa

Not long ago Lhasa was a medieval town of 30,000 people . There were so many Tibetan mastiffs on the loose it was necessary to carry a stick. The pace of life was slow, the clocks displayed the wrong time, herds of cows and sheep wandered the streets, poor women carried baskets of vegetables and dried yak meat, street acrobats performed tricks and prostrating pilgrims and monks were everywhere. Communist rule made itself known with loudspeakers blare military anthems and Communist slogans and soldiers are posted outside temples. Most Han Chinese that were there would have prefered to be somewhere else.

The first wave of modernization and development occurred in the 1990s when Westerners began arriving in large numbers. A Holiday Inn was opened and restaurants like the Hard Yak Café began offering Tibetan and pizzas and yakburgers, with fries and coke. A good proportion of the people on the streets selling souvenirs were Chinese. The next wave occurred as large numbers of Han Chinese began pouring in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Many traditional buildings in Lhasa were torn down and replaced with boxy building with Chinese adornments, karaokes and brothels with Chinese women displayed in windows illuminated with red light. By 2000 only 90 old stone buildings remained and they were mostly in east Lhasa. Within a relatively short time Chinese dominated the markets and commercial activity.

New bridges and roads were built. Car dealerships and a Nike store opened. Before the city’s first five star hotels opened in 2006 there were no elevators in Lhasa. Traffic picked up. Tree lined roads once deserted except for a few bicycles and robed monks became highways with taxis, trucks and military convoys. Prices and rents shot up. A huge cement factory on a road outside Lhasa and an unsightly copper mine on the shores of nearby Lake Yamdrok Tso filled the air with particulate pollutants.

The road to lead to Jokhang temple was lit with red, green, blue and white neon lights and lined with restaurant, karaoke bars, massage parlors, mountaineering stores, fashion shops, and shops with Tibetan souvenirs sold by Chinese dressed like Tibetans. Many of the things that made Lhasa charming have disappeared. Potala Palace no longer dominated the city as it once did.

In March 2009, the Chinese government approved a plan to redesign Lhasa so it will become an “economically prosperous, socially harmonious, and eco-friendly modern city with vivid cultural characteristics and deep ethnic traditions.”

Today, large swaths of Lhasa are dominated by Chinese-style billboards, Chinese-style buildings and streets with Chinese names. Chinese is the language of business and trade. At the night markets nearly all the vendors all Chinese and many of the things they sell are geared for Chinese consumers. Even the stores that sell Tibetan trinkets and souvenirs are almost all owned and run by Chinese. The road that passes on front of Potala Palace is called Beijing Road. Even Chinese tourist are disappointed by the extent of the Chinese presence. In March 2009, restrictions on adverting and construction were tightened round the palace after complaints by the United Nations that better measures were need to take care of the site.

Bathing in a river

Juvenile crime and alcoholism are on the rise, Pool halls and alleys are filled with unemployed young men. Prostitutes walk the streets and work out of hair salons, beauty parlors and karaoke bars. The red light district is expanding and on weekend nights appears to have no shortage of customers, mostly Chinese who work in construction crews. Migrants from rural areas — most of them Han Chinese but some of them Tibetan — sleep ten to a room in Lhasa flea bag hotels and hang out on the Second Ring Road hoping to get jobs as day laborers and use their meager wages to support not only their immediate families no jobs but also their parents and siblings. These days the city is filled with plain clothes police in track suits. When asked who they are they say: “students.”

Still Lhasa is not completely spoiled. Some Tibetans still live in traditional whitewashed stones houses with painted window frames. Lhasa still resembles a large town more than a city. It takes only about a half an hour to walk from one side to the other. A fifteen minute walk from the center brings you to mountains and rivers that can be crossed in yak-skin boats. Further afield are meadows with wild flowers and glaciers.

Rural Life in Tibet

Around 70 percent of Tibet's population is classified as rural, according to 2018 Chinese government figures, including farmers or herders and many subsistence farmers. This down from about 85 percent in 2000. Many live in rural areas largely untouched by the modern world. Sounds heard in rural Tibet include: women singing while they work in the fields, monks chanting, children playing. Even places within 20 miles of Lhasa have no electricity or televisions.

Morning chores at Tibetan agricultural villages include collecting firewood or dung, making a fire and boiling water for yak butter tea, and collecting dandelions and mixing them with barley to feed to the pigs. Communities have typically been self-sufficient and associated with monasteries or feudal lords. Land was often distributed on the basis of the needs of families and quality of the land, with families typically getting both good and bad quality land. This system is changing as the government is encouraging rural people to get more involved with the regional economy.

Life has improved for the rural Tibetans somewhat. Their taxes have been repealed. It is not uncommon to see mud brick houses with satellite dishes and nomad tents with solar panels or generators used to run boomboxes that blast out Tibetan and Chinese pop tunes. Rural Tibetans are still among the poorest people in the world and their rates of illiteracy, infant mortality and poverty are high.

Tibetans on the dry Tibetan plateau have little water for washing and have traditionally considered washing to be an unhealthy, harmful practice. As a result many Tibetans are very dirty: their faces and hands are often covered in a layer of greasy yak-butter and dirt, their clothes are caked in dirt and their hair is matted. When Tibetan nomads do wash, they tend to rinse their faces and hands in yak or goat milk. To protect their skin and beautify themselves some nomad women apply a salve to their face made from boiled milk curds. Some people go through the entire life without ever taking bath.

Most rural Tibetans have bright red cheeks — the consequence of high latitude, sun and winds. When they descend to the lowlands their skin often becomes pale yellow. Some have gold teeth.

See Separate Article AGRICULTURE IN TIBET factsanddetails.com ; TIBETAN HOMES, TOWNS AND VILLAGES factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN HERDERS AND NOMADS factsanddetails.com; RESETTLED TIBETAN HERDERS factsanddetails.com

Adolescent Sex in Tibet

In “A Study of Polyandry”, Peter of Greece and Denmark wrote in 1963 on Western Tibet: “I enquired who it was who gave the children their sex education. The answer was that nobody did. Parents are forbidden by custom to speak to them of such things, and they have to pick up what they can learn from playmates. Another source of information was watching animals, it seemed, and everyone agreed that that may lean something from witnessing their parents’ behaviour during the long winter nights in the Jan-sa. Anyhow, they “somehow” knew something about sex by the time they were approximately six years of age”. Masturbation in the very young was discouraged by threats of witches that would cut off their ears; the older ones are beaten.[Source: “Growing Up Sexually, Volume” I by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas, 2004]

Ludwar-Ene (1975) provides a detailed interpretation of sexual socialisation among the Nepalese Tibetans. Infants from the age of three are raised in extreme modesty, girls more than boys. Mothers and neighbours distract the infant from and shame the child for genital manipulation, which is presumed to go underground.

Norbu, elder brother of the Dalai Lama, argues that “parents often arrange marriages for their children. But it is seldom that children are married against their wishes, and the wise guidance of older people often results in a happier marriage than when the youthful heart follows its desires” . Normally, however, boys and girls around the age of 18 or 19 “start looking toward marriage”

Prostitutes in Tibet

The number of brothels and karaoke bars in Tibet increased greatly since the Chinese began arriving in large numbers. In the early 2000s, they were found in almost every large town. A typical establishment charges $1 for a Chinese-produced Pabst Blue Ribbon and as little as $10 for a Chinese girl, most of them from Sichuan. Most of the customers are Chinese bureaucrats, soldiers, police and truck drivers.

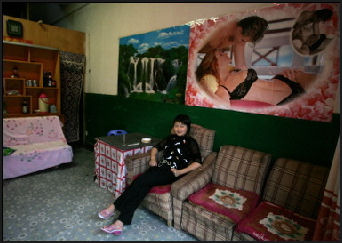

Prostitute in Tibet

Development economist Andrew Fischer wrote in 2005: “Most of the tourists visiting the TAR are Chinese nationals and they mostly stay in Chinese-owned and -run hotels on the west side of Lhasa, close to an abundant supply of Chinese restaurants and entertainment centers, complete with Chinese brothels and Chinese sex workers, who obviously service the military personnel and cadres stationed there as well.

It is likely that much of the revenue that such tourism generates is channeled through such venues and eventually out of the province altogether. Under such conditions, the tourism industry will have a difficult time functioning as a self-sustaining pillar industry that accumulates capital and profits in the TAR, rather than servicing as another drain from which incoming resources flow back out of the province almost as fast as they enter.” [Source: “State Growth and Social Exclusion in Tibet’by Andrew Fischer, NIAS Press, 2005]

Some teenage Tibetan girls work on construction crews during the day and work as prostitutes at night. The Los Angeles Times interviewed on 17-year-old who worked 12 hours a day on a road crew outside Tsetang, Tibet’s third largest city, and lived in a small shack in the red light on the Yarlung River, where she welcomed customers the 12 hours she wasn’t working on the road crew.

The girl pays $5 a month for the shack and eats mostly barley that she and her roommate prepare over a campfire outside their hut. She washes periodically at a public bathhouse that charges 60 cents per bath. She sends most of the money she makes to her family in her village and spends the little bit of money left over on clothes, including a fake Boss sweatshirt and Yankees baseball cap. Her pimp cheats her out of most of the money her customers pay for her services.

The girl said her costumers include migrant workers, visiting businessmen and sometimes policemen. On the police she told the Los Angeles Times, ‘sometimes they pay, sometimes the don’t. Usually they tell us it’s a raid and shut the doors behind them. But when they sit down they become customers.”

See Lhasa

Image Sources: Julie Chao, Snowland Cuckoo Association, Purdue University, AFP

Text Sources: 1) “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China”, edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K.Hall & Company, 1994); 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China ethnic-china.com *\; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2022