HISTORY OF TIBETAN BUDDHISM

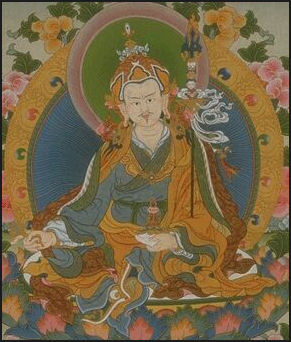

Guru Rinpoche

Tibetan Buddhism is a syncretic mix of Mahayana Buddhism, Tantrism and local pantheistic religions, particularly the Bon religion. Its organization, public practices and activities are coordinated mainly by monasteries associated with temples. Religious authority is in the hands of priests called lamas. Tibetan Buddhism is the main religion of Tibet. It is also practiced by Mongolians and tribal groups such as the Qiang and Yugur in Yunnan, Sichuan, Gansu, Qinghai and other provinces and by Tibetan- and Mongolian-related people in India, Nepal, Bhutan and Russia.

Tibet was one of the last major zones of Buddhist Asia to accept Buddhism but arguably it counts among the places where it is most alive today. Tibetan Buddhist ideology and rituals are woven into Tibetan culture and life. According to the Encyclopedia of Buddhism: Throughout their religious history, Tibetans have emphasized a balance of scholarship, contemplative meditation, and the indivisibility of religious and secular authority; most of these values were formulated under the aegis of Buddhist tantrism. Tibetan Buddhism matured over the course of fourteen centuries and will be assessed in this entry in phases that, if somewhat contested in scholarly literature, still represent important stages in its development. [Source: Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Gale Group Inc., 2004]

Kathryn Selig Brown wrote in on Metropolitan Museum of Art website: Buddhism was introduced to Tibet by the seventh century and was proclaimed the state religion by the end of the eighth century. Although Buddhist influence waned during persecutions between 838 and 942, the religion saw a revival beginning in the late tenth century. It rapidly became dominant, inaugurating what is known as the "later diffusion of the Buddhist faith." During the first few hundred years of this renewed interest, many monks from Tibet traveled abroad to India (The Great Teacher Marpa, 1995.176), the homeland of Buddhism, to study the religion, and Indian scholars were invited to Tibet to lecture and give teachings.[Source: Kathryn Selig Brown, Independent Scholar,Metropolitan Museum of Art]

See Separate Articles:TIBETAN BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com;TIBETAN BUDDHIST SCHOOLS (SECTS) factsanddetails.com; ANCIENT AND PREHISTORIC TIBET AND EARLY TIBETAN HISTORY factsanddetails.com ; TIBETAN EMPIRE (A.D. 632-842): TUBO, TANG CHINA, SONGTSEN GAMPO AND PRINCESS WENCHENG factsanddetails.com ; 10TH TO 18TH CENTURY TIBET: FEUDALISM, BUDDHISM, CHINA, MONGOLS factsanddetails.com ; DALAI LAMAS, THEIR HISTORY AND CHOOSING NEW ONES factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources on Tibetan Buddhism: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Tibetan Buddhist archives sacred-texts.com ; Buddha.net list of Tibetan Buddhism sources buddhanet.net ; Tibetan Buddhist Meditation tricycle.org/magazine/tibetan-buddhist-meditation ; Gray, David B. (Apr 2016). "Tantra and the Tantric Traditions of Hinduism and Buddhism". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. oxfordre.com/religion ; Shambhala.com. largest publisher of Tibetan Buddhist Books shambhala.com ; Tibetan Philosophy, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu/tibetan ;Official Dalai Lama site dalailama.com ; Tibetan Studies and Tibet Research: Tibetan Resources on The Web (Columbia University C.V. Starr East Asian Library ) columbia.edu ; Tibetan and Himalayan Library thlib.org ; Center for Research of Tibet case.edu ; Tibetan Studies resources blog tibetan-studies-resources.blogspot.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “A Concise History of Buddhism: From 500 BCE-1900 CE” by Andrew Skilton, Jinananda, et al. Amazon.com; “Following in Your Footsteps, Volume III: The Lotus-Born Guru in Tibet” by Padmasambhava, Lhasey Lotsawa (Translator) Amazon.com; “Tibet's Great Yogi Milarepa” by W.Y. Evans-Wentz Amazon.com; “The Life of Milarepa” by Heruka, Lobsang P. Lhalungpa Amazon.com; Tibetan Buddhism: “Essential Tibetan Buddhism” by Robert A. F. Thurman Amazon.com; “Initiations and Initiates in Tibet” by Alexandra David-Neel Amazon.com; “The Secret Oral Teachings in Tibetan Buddhist Sects” by Alexandra David-Neel, Lama Yongden Amazon.com; Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism by John Powers Amazon.com; “The World of Tibetan Buddhism: An Overview of Its Philosophy and Practice” by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Geshe Thupten Jinpa Amazon.com; “Tibetan Buddhism: With its Mystic Cults, Symbolism and Mythology, and in Its Relation to Indian Buddhism” by L Austine Waddell Amazon.com; “The Jewel Tree of Tibet: The Enlightenment of Tibetan Buddhism” by Robert Thurman and Sounds True Amazon.com; “A Concise Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism” by John Powers Amazon.com; “The Preliminary Practices of Tibetan Buddhism” by Geshe Rapten Amazon.com; “Teachings and Practice of Tibetan Tantra” Amazon.com; “Tantra in Practice” by David Gordon White Amazon.com; Religions of Tibet: “The Religions of Tibet” by Giuseppe Tucci and Geoffrey Samuel Amazon.com; “Religions of Tibet in Practice” by Donald S. Lopez Jr. Amazon.com; “Tibet's Sacred Mountain: The Extraordinary Pilgrimage to Mount Kailas” by Russell Johnson and Kerry Moran Amazon.com; “Tantra in Tibet” by Dalai Lama, Tsong-Kha-Pa, et al Amazon.com; “Magic and Mystery in Tibet” by Alexandra David-Neel and A. D'Arsonval Amazon.com; “Mission to Tibet: The Extraordinary Eighteenth-Century Account of Father Ippolito Desideri S. J.” by Fr. Ippolito Desideri S.J., Leonard Zwilling, et al. Amazon.com; Bon: “The Bon Religion of Tibet: The Iconography of a Living Tradition” by Per Kvaerne Amazon.com; “Bon: Tibet's Ancient Religion” by Christoph Baumer Amazon.com; “Flight of the Bön Monks: War, Persecution, and the Salvation of Tibet's Oldest Religion” by Harvey Rice , Jackie Cole , et al. Amazon.com; “Sacred Landscape And Pilgrimage in Tibet: In Search of the Lost Kingdom of Bon” by Gesha Gelek Jinpa, Charles Ramble, et al. Amazon.com;

Skewed View of Tibetan Buddhist History in the West

"We in the West tend to project all our fantasies about mystical spiritualism onto Tibetan Buddhism," Erik Curren, author of “Buddha's Not Smiling: Uncovering Corruption at the Heart of Tibetan Buddhism Today” , told the Los Angeles Times. "It's really like a civil war. There's lots of acrimony."

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books: In the West “the Dalai Lama, enjoys a popular image as an irreproachable man of peace. But this overlooks the fact that the Dalai Lama began adult life as a theocrat leading a government with an army; only later did he transform himself into a Gandhi-influenced proponent of nonviolence who was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize. That transformation makes strategic sense, perhaps, for Tibetans in their struggle against an overwhelmingly powerful Chinese state, but it is a recent development for most of Tibet’s history, Buddhism has served the state. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, July 13, 2019]

Tibetan Buddhism developed in Tibetan during two important phases of there. “One was the period of Tibetan glory in Central Asia, including the great Tibetan empire of the seventh to ninth centuries, and that of Tibet’s renaissance from the eleventh to the twelfth centuries. The second period was Tibetan Buddhism’s transformation from the thirteenth century onward into a bestower of sacral rule and occult powers, both of which seep into today’s romanticized views of Tibet and its spiritual practices. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, July 13, 2019]

Karl Debreczeny, a curator at the Rubin Museum in Boston said that, for many people in the West, Buddhism is completely divorced from its history. So many of the beliefs and rites have been stripped away in this view that many Westerners regard it purely as a philosophy, rather than a religion. As well-intentioned as this version of Buddhism might be, it is also a fantasy that places its practice on a higher moral and spiritual plane and erects an unbridgeable distance between us and its real, historical significance in Tibet.

Debreczeny challenge the western romantic notion of Buddhism and Tibet. He said. Tibetan “rulers were not interested in mindfulness, meditation, and yoga mats; they wanted to know what this religion could do for the state..” These ideas owe a great deal to the influence of Elliot Sperling, the venerated Tibetologist who died in 2017, at age sixty-six. An outspoken critic of China’s Tibet policy, he was also a pioneer in the study of Tibet — one who trained a generation of scholars, including Debreczeny himself. Unlike the explorers and chroniclers of the past, these new researchers learned to read Tibetan and Chinese, and to take the country and culture on its own terms, rather than be distracted by the projections of Tibet’s powerful neighbors, rivals, and patrons. Sperling’s classic 2001 essay “‘Orientalism’ and Aspects of Violence in the Tibetan Tradition” underpins many of the concepts” in regard to “realism about Tibetan politics and the integration of Buddhism with the needs of secular power.

Important Figures in Tibetan Buddhism

The monk Padmasambhava (eighth century), Jacob Kinnard wrote in the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices,, is one of the best-known and important figures. He is a Tantric saint who was instrumental in introducing Buddhism to Tibet; mythologically he is credited with converting to Buddhism the local demons and gods who tormented the Tibetan people people, turning them into protectors of the religion. [Source:Jacob Kinnard, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2018, Encyclopedia.com]

Atisha (982–1054) was an Indian monk and scholar who went to Tibet in 1038. He is credited with entirely reforming the prevailing Buddhism in Tibet by enacting measures to enforce celibacy in the existing order and to raise the level of morality within the Tibetan sangha. He founded the Kadampa school, which later became the Geluk-pa school.

Like his Chinese counterparts Faxian (Fa-hsien) and Xuanzang (Hsuan-tsang), Buston (1008–64), a Tibetan Buddhist, translated much of the Buddhist sacred literature, including Tantra texts, into classic Tibetan and is sometimes credited with making the definitive arrangements of the Kanjur and Tanjur, the two basic Tibetan collections of Buddhist principles. He also produced a history of Buddhism in Tibet that is among the most important documents for Buddhism's early development in that region.

Finally, two extremely important semihistorical figures are Marpa (1012–96) and Milarepa (1040–1143). Marpa was a Tibetan layman thought to have imported songs and texts from Bengal to Tibet, but he is best known and most venerated as the guru of Milarepa. Milarepa was a saint and poet of Tibetan Buddhism who continues to be extremely popular. His well-known autobiography recounts how in his youth he practiced black magic in order to take revenge on relatives who deprived his mother of the family inheritance and then later repented and sought Buddhist teaching. Milarepa stands figuratively as the model for all Tibetans.

Arrival of Buddhism in Tibet

7th century Tang Buddha

Buddhism was introduced into Tibet in the A.D. 3th century, about 700 years after Buddha's death, by Indian missionaries, but the religion didn't really take hold until the 7th and 8th century when monks from India and Nepal appeared in large numbers. Buddhist scriptures from China also played a part in the spread of Buddhism in Tibet.

According to the Encyclopedia of Buddhism: “Tibetan literature attributes the formal introduction of Buddhism to the reign of its first emperor,Songtsen gampo (r. 618 – 650). Undoubtedly, though, proto-Tibetan peoples had been exposed to Buddhist merchants and missionaries earlier. There is a myth that the fifth king before Songtsen gampo, Thothori Nyantsen, was residing in the ancient castle of Yumbu Lakhang when a casket fell from the sky. Inside were a gold reliquary and Buddhist scriptures. While the myth is not early, it possibly reveals a Tibetan memory of prior missionary activity. We do know that official contact with Sui China was accomplished from Central Tibet in 608 or 609 and that, as Tibet grew more powerful, Buddhist contacts increased. [Source: Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Gale Group Inc., 2004]

“Nonetheless, two of Songtsen gampo's wives — Wencheng from China and Bhrikuti from Nepal — were credited with constructing the temples of Magical Appearance — Jokhang and Ramoche. Other temples were built as well, and twelve were later considered limb-binding temples, where a demoness representing the autochthonous forces of Tibet was subdued by the sanctified buildings. Songtsen gampo is also credited with having one of his ministers, Thonmi Sambhota, create the Tibetan alphabet from an Indian script and write the first grammars. |~|

“Buddhist progress occurred with the successors to Songtsen gampo. Notable was the foundation of the first real monastery in Tibet, Samye (ca. 780) and the influx of Indian, Chinese, and Central Asian monks around that time. Particularly influential were Shantarakshita (Śāntarakita), an important Indian scholar, and his disciple Kamalaśīla. Shantarakshita and his entourage were responsible for the first group of six or seven aristocratic Tibetans to be ordained in Tibet. These authoritative monks did much to cement the relationship between Indian Buddhism and Tibetan identity. Another teacher, Padmasambhava, was a relatively obscure tantric guru whose inspiration became important later. |~|

“Translation bureaus in Dunhuang and Central Tibet were opened by the Tibetan emperors, from Trisong Detsen, (ca. 742–797) through Ralpacan (r. 815–838), but unofficial translations were recognized sources of concern. While the official bureaus emphasized the Mahayana monastic texts, unofficial translations tended to feature more radical tantric works. During the reign of Sadnalegs (r. 804–815) a council was convened to regularize Tibetan orthography and to establish both translation methods and a lexicon of equivalents for official translators. The result was the emergence of classical Tibetan, a literary language developed to render both sophisticated Buddhist terminology and foreign political documents into the rapidly evolving Tibetan medium. |~|

“Translations were initially made from several languages, but principally from Sanskrit and Chinese, so that a consistent tension between Indian and Chinese Buddhist practice and ideology marked this period. The Northern Chan school was present in Tibet, but from 792 to 794 a series of discussions between Indian and Chinese exegetes at the Samye debate was ultimately decided in favor of the Indians. Eventually, Buddhist translations from Chinese were abandoned for exclusively Indic sources.

In the early days, Buddhism was practiced by the royal court of Tibet — particularly after King Songtsen Gampo took Nepali and Chinese wives in the 7th century — but was not practiced in the countryside where the Bon religion prevailed and Buddhism was greeted with hostility. The Buddhist priests of this period were probably Indians or Chinese.

Tibetan Buddhism, Bon and Tantrism

Most Tibetan Buddhist pay homage to gods found in both religions as well as animist and shamanist ones. Some Himalayan people say "the mountain gods are Buddhists." Tibetan Buddhist heroes are often regarded as manifestations or reincarnations of gods, spirits and bodhisattvas and their “historical” achievements often involve fighting and defeating evil gods and spirits and allying themselves with good gods and bodhisattvas and wrathful and vengeful ones.

Before Buddhism was introduced to Tibet the people there practiced the Bon religion. Tibetan Buddhism absorbed elements of Bon when it developed in the A.D. 8th century. Early Tibetan tribes were warlike. It has been argued that Buddhism pacified them, making it easier for the Chinese and tribes from the north to conquer them.

Bon religion is an ancient shamanistic religion with esoteric rituals, exorcisms, talismans, spells, incantations, drumming, sacrifices, a pantheon gods and evil spirits, and a cult of the dead. Originating in Tibet, it predates Buddhism there, has greatly influenced Tibetan Buddhism and is still practiced by the Bonpo people. Prayer flags, prayers wheels, sky burials, festival devil dances, spirit traps, rubbing holy stones — things that are associated with Tibetan religion and Tibetan Buddhism — all evolved from the Bon religion. The Tibetan scholar David Snellgrove once said “Every Tibetan is a bonpo at heart.” See Bon Religion

Tibetan Buddhism and Tantrism

Buddhism developed out of Hinduism. The kind of Buddhism introduced to Tibet from India was Tantrism, a sect within Buddhism and Hinduism that incorporates esoteric religion, ritual magic and sophisticated philosophy (See Beliefs). Some of the mystical and magical aspects of Tantrism dovetailed with mystical and magical practices of the Bon religion. After a period of resistance Buddhism replaced the Bon religion and was firmly established in Tibet by the 11th century.

Peter A. Pardue wrote in the International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences: The assimilative diversity of popular Mahayana did not mark the end of the development of Buddhism in India but rather led almost imperceptibly to a metamorphosis. Beginning recognizably in the sixth and seventh centuries A.D. there took place an upsurge of a vast new repertoire of magical, ritualistic, and erotic symbolism, which formed the basis for what is commonly called Tantric Buddhism. Its distinguishing institutional characteristic was the communication through an intimate master–disciple relationship of doctrines and practices contained in the Buddhist Tantras (esoteric texts) and held to be the Buddha’s most potent teachings, reserved for the initiate alone. [Source: Peter A. Pardue, International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

In content, Tantric Buddhism is fused in many areas almost indistinguishably with Mahayana doctrines and archaic and magical Hinduism. Cryptic obscurities were deliberately imposed on the texts to make them inscrutable except to the gnostic elite. But it took a number of identifiable forms, the most dramatic of which was Vajrayana (“thunderbolt vehicle”)” — Tibetan Buddhism. Vajrayana had its metaphysical roots in the supposition that the dynamic spiritual and natural powers of the universe are driven by interaction between male and female elements, of which man himself is a microcosm. Its mythological and symbolic base was in a pantheon of paired deities, male and female, whose sacred potency, already latent in the human body, was magically evoked through an actional Yoga of ritualistic meditations, formulas (mantra), and gestures (mudra) and frequently through sexual intercourse, which occasionally included radical antinomian behavior. The inward vitality of the sacred life force is realized most powerfully in sexual union, because there nonduality is experienced in full psychophysical perfection.

The philosophical justification for these developments was derived from adaptations of Yogacara and Madhyamika theory: since the objective phenomenal world is fundamentally identical with the spiritual universe of emptiness or is at most an illusory projection of the mind, the conclusion was drawn that all forms are not only devoid of real moral distinctions but, also, may serve as expedient means to an undifferentiated spiritual end: the overcoming of the illusory sense of duality between the phenomenal and spiritual world. For the adept it is not only necessary to say that there is no good or evil; it must be proved in an active way. The traditional morality is violated as behavior formerly regarded as reprehensible is found to speed the realization of nonduality.

King Trisong Detsen and Samye Monastery

According to the BBC: “ Buddhism was brought from India at the invitation of the Tibetan king, Trisong Detsen, who invited two Buddhist masters to Tibet and had important Buddhist texts translated into Tibetan. First to come was Shantarakshita, abbot of Nalanda in India, who built the first monastery in Tibet. He was followed by Padmasambhava, who came to use his wisdom and power to overcome "spiritual" forces that were stopping work on the new monastery." Trisong Detsan constructed the first Buddhist monastery in Tibet —Samye Monastery. [Source: BBC ]

King Trisong Detsen (755-97) is very important to the history of Tibetan Buddhism as one of the three 'Dharma Kings' who established Buddhism in Tibet. The Three Dharma Kings were Songtsän Gampo, Trisong Detsen, and Ralpacan. Under King Trisong Detsen (755-97), Tibet conquered Gansu and Sichuan and extended its influence into present-day India, Pakistan and Central Asia. The Tibetans were at the peak of their power in 763 when they sacked the Tang capital of Chang'an after responding to a Chinese advance into western China. King Trisong Detsen founded the Samye Monastery and is regarded as a manifestation of the Bodhisattva Jamelyang (Majushri). In paintings, he wears white turban and holds the sword of wisdom in right hand and scripture on a lotus in his left arm. He is often depicted in a triad of kings with Songtsen Gampo and King Ralpachen (A.D. 817-36).

Samye Monastery (in Dranang, 30 kilometers west of Tsetang) is the oldest monastery in Tibet. Situated in the Yarlung Valley, it is said to have been built where the Tantric yogi Padmasambhava built an enormous mandala to exorcize evil forces from the area. At the center of the main temple is a large golden Buddha with four corners.

Samye Monastery was probably founded in 767 under the patronage of King Trisong Detsen, with the work being directed by Indian masters Padmasambhava and Shantarakshita. Construction was completed in 779. Wenbin Xiong wrote in “Tibetan Arts”: “After fighting against the Bon cultures for a long period, Buddhism eventually won its steady position during the reign of Trisong Detsan in middle of the 8th century. As a landmark of the victory, Samye Monastery, the first monastery accommodating, training and cultivating songhas in Tibetan history was inauagurated in 763 A.D. in Samye region, in today's Shannan prefecture. From then on the Tibetan architecture art of Buddhism has gone a further step crossing from the temple architecture stage to the monastery architecture stage.[Sources: “Tibetan Arts” by Wenbin Xiong (2005)]

See Samye Monastery: Tibet's First Buddhist Monastery Under NEAR LHASA factsanddetails.com

Guru Rinpoche (Padmasambhava)

The story of the introduction of Buddhism to Tibet is a mix of history and legends about religious heroes and their conquest of local gods and spirits and converting them to Buddhism. Most of the religious heroes are believed to have been real people but some of their achievements and characteristics are clearly legendary and supernatural.

Guru Rinpoche is an Indian sage who is said to have introduced Buddhism to Tibet in the Earth Ox Year of A.D. 749 and is regarded as one of the founders of the Nyingmapa order. According to legend he emerged from a lotus blossom when he was born in the Milk Ocean Land in in South West Oddiyana (present-day Swat, Pakistan) and began teaching in Tibet when he was 1,000 years old. Employing Tantric powers, he and his monks purportedly converted thousand of demons to Buddhism, which is supposedly why Tibetan Buddhists worship so many gods as well as follow the teachings of Buddha.

Known in Sanskrit as Padmasambhava, Guru Rinpoche is regarded as the second Buddha by members of the Nyingmapa sect and a manifestation of the Amitbha Buddha. He is said to have lived on a copper-colored mountain paradise called Zangdok with a group of cannibalistic trolls. In paintings he wears a red Nyingmapa-style hat, a ritual dagger in his belt and has a curly moustache. In his left hand is skull cup and a staff topped with three skulls and cross bolts of lightning known as vajas. In his right hand is a thunderbolt, symbolizing compassion. Guru Rinpoche has eight manifestations which are known collectively as the Guri Tsengye. Padmasambhava developed principles of Tibetan and Mahayana Buddhism and founded Lamaism.

Padmasambhava means “the Lotus-Born” in Tibetan. It was said that Guru Rinpoche appeared miraculously in the blossom of a lotus in Lake Danakosha, the "Ocean of Milk" . When the king saw the child sitting on the lotus, he was filled with delight and invited him to the palace as his son and religious guide. The child was named Padmasambhava, the "lotus-born." Guru Rinpoche spent more than 55 years in Tibet, manifesting all kinds of wonders and miracles and is highly revered by all the schools of Tibetan Buddhism, and especially by the Nyingma.

Buddhism Takes Hold in Tibet

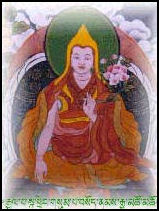

Milarepa

In the late 8th century, under King Trisong Detsen, Tibetan Buddhism developed in an area that extends from Xigaze to Zetang on the Yarlung Zangpo river. Monasteries, temples and chapels were built; scriptures were translated into Tibetan; Buddhism became the religion of the Tibetan court; and the religion spread along the Central Asian trade routes that Tibet controlled.

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books: Buddhism's arrival in Tibet in the 7th century, roughly coincided with the kingdom’s rise to become a Central Asian superpower. It was the strongest military rival to China’s Tang dynasty and briefly occupied its capital, Chang’an. Buddhist monks were active on both sides, lending their spiritual authority to this power-struggle by use of rituals and the invocations of deities like the wrathful Acala. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, July 13, 2019]

“When the Tang ceded control to Tibet of the Hexi Corridor, a vital segment of the Silk Road to Central Asia, Tibetan culture spread throughout the region. This was a multicultural empire, incorporating Greek medicine, a writing system based on Sanskrit, record-keeping drawn from the Tang, and silver-working from the Sogdians. Silver drinking horns and beakers on display are testament to this cross-fertilization.

Tibetan Buddhism evolved through a continuous process of debate and interpretation over the meaning of Buddhism between factions and sects with different beliefs. At the same time traditional Tibetan customs, deities, incantations and ceremonial practices were absorbed. But the process was far from smooth, a number of competing sects were created and they vied for dominance and sometimes engaged in violent conflicts.

Buddhism in Tibet After the Tibetan Empire Collapse

Buddhism in Tibet was dealt as severe blow when Tibet's control of the Central Asian trade routes faltered and the empire collapsed completely around A.D. 840. It experienced a revival in far western Tibet under the guidance of Ye-shes-'od, a regional ruler. In 985, Ye-shes-'od, renounced his throne and was ordained as a Buddhist monk and used his influence to spread the religion. During the 10th and 11th century many temples and monasteries were built. Western Tibet remained the center of Tibetan Buddhism for the next 500 years.

According to the Encyclopedia of Buddhism: “The last of the Tibetan Empire emperors, Langdarma (r. 838–842) began a campaign of suppression of Buddhism similar to one that took place under the Tang Dynasty in China. Langdarma was assassinated by a Buddhist monk, and the vast Tibetan empire fragmented over imperial succession. The period from 850 to 950 was a chaotic time marked by popular revolts and warlordism. Surviving Buddhist monks fled, and monastic practice was eclipsed in Central Tibet for approximately a century. Aristocratic clans that had accepted Buddhism, however, continued to develop indigenous rituals and new literature based on the received tradition. [Source: Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Gale Group Inc., 2004]

“Yet the monastic religious form was closely allied to the memory of the empire, and Samye stood empty. Eventually several Tibetans under the leadership of Klumes from Central Tibet traveled to Dantig Temple, in modern Xining, and received monastic ordination from Tibetan monks who had maintained it. Returning to Central Tibet around 980, Klumes and others began to refurbish Samye as well as construct networks of new temples. Their position, though, was often threatened by the lay lamas called Bande, and the new monks were sometimes physically attacked.

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books: “When the Tibetan empire collapsed later that century in the wake of a power struggle and political fragmentation, the Tibetan influence in the region lingered, especially after the Western Xia empire of the Tangut people was founded, an area that corresponds to the eastern end of the Silk Road, especially in today’s Ningxia province. The Tangut emulated many Tibetan practices, and began a custom of appointing a Tibetan Buddhist monk as imperial preceptor, Western Xia’s highest religious figure. Most preceptors anointed emperors and advised them on religious matters, but at times they also wielded political power in their own right — as a preceptor did under the Yuan dynasty when the Mongol leader Qubilai Khan was granted suzerainty over Tibet. Buddhism thus served the state, with the Tangut presenting themselves as universal sacral rulers, legitimized through Tibetan Buddhist rituals. When the Mongols obliterated Western Xia in the thirteenth century, they picked up many of these practices." A memorable paintings shows a tiny Emperor Kublai Khan in a corner of the picture talking with his giant-sized imperial preceptor. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, July 13, 2019]

Atisha and the Establishment of the Buddhist Bureaucracy

Arisha Tibet in the 10th century was in a state of anarchy. The Tibetan people were divided. Buddhism had been corrupted, ridden with misinterpretations and mixed with the shamanistic Bon religion. There were reports of "robber monks” who got drunk, engaged in sex and kidnaped and killed people and ate them. The Sanskrit translator Rinchen Zangpo, and the legendary Indian master Atisha were also instrumental in reintroducing Buddhism to western Tibet.

The 60-year-old Indian master Atisha was lured by small fortune in gold to trek to Guge in Tibet in 1042. He helped bring order to Tibet and Tibetan Buddhism by setting strict rules prohibiting sex, alcohol, travel and possessions. These rules set the tone for the anti-materialist aspects of Tibetan Buddhism. Atisha's campaign was supported by noble families, whose young men were recruited as lamas, teachers, administrators and teachers.

According to the Encyclopedia of Buddhism: According to the Encyclopedia of Buddhism: Atisha (982–1054) Atisha introduced the popular Bengali cult of the goddess Tara and reframed tantric Buddhism as an advanced practice on a continuum with monastic and Mahayana Buddhism. This systematization, already known in India, became designated the triple discipline (trisa vara: the monastic, bodhisattva, and tantric vows) and Atisha embedded this ideal in his Bodhipathapradīpa (Lamp for the Path to Awakening). Atisha also promoted the basic Mahayana curriculum of his monastery. [Source: Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Gale Group Inc., 2004]

Under Atisha’s system, sons for the highest ranking families were made the head lamas of monasteries on their land. The offices were hereditary but because the lamas were celibate monks leadership positions were handed down from uncle to nephew. Large numbers of Tibetans traveled to the great centers of Buddhist learning in the Pali Empire in India. They dominated entire colleges in Bengal and Bihar and copied libraries of texts which they brought back to Tibet.

By the 13th century, monks in the monasteries in Tibet were the equivalent of the Mandarins in Imperial China. They ran the bureaucracy and administered the country but were ultimately accountable to the kings and nobles. Over time the monasteries grew in power and maintained their hold on power until the invasion by China in 1950.

Milarepa

Milarepa (1040-1123) is one of Tibetan Buddhism's most well-known figures. Regarded as one of the founders of the Kagyupa (Red Hat) order, he was an 11th century monk, poet, alchemist and magician who is famous for walking around in the cold with nothing on but a thin cotton shirt (hence his name) and subsisting on a diet of nettles. He purportedly wrote "one hundred thousand songs," some of which are still known to Tibetans today, and taught Tantric sexual techniques to mountain goddesses.

Milarepa (“the Cotton Clad”) was a yogi and disciple of Mar-pa of Lho-brag (1012-97), founder of the Marpa school, a popular Buddhist sect that emphasized yoga and spiritual principals over philosophy. A sort of Buddhist version of St Francis of Assisi, Milarepa is said to have turned to Buddhism and spent six years mediating in cave to repent for trying to poison his uncle and was able to attain the supreme enlightenment of Buddhahood in one lifetime. Most paintings depict him smiling, holding his hands over his ears and singing. He is sometimes green to indicate that he lived on a diet of nettles. His complete poetical works, Mila Gnubum, "The Hundred Thousand Songs of Milarepa," was translated into English by Garma C. C. Chang (New York: University Books, 1962). [Source: Eliade Page]

According to the Encyclopedia of Buddhism: While some of the disciples of Marpa were concerned with tantric scholarship, it was Marpa’s poet disciple (Milarepa, , and Milarepa's disciple Gampopa (1079–1153), who effectively grounded the tradition in both tantric and monastic practice. [Source: Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Gale Group Inc., 2004]

Milerepa Extols His 'Five Comforts'

“Milerepa Extols His 'Five Comforts'” is a selection is from Mila Khabum, the 'Biography of Milarepa,' written by a mysterious yogi, 'The mad Yogi from gtsan' in the latter part of the twelfth or in the beginning of the thirteenth century. It goes: One night, a person, believing that I possessed some wealth, came and, groping about, stealthily pried into every corner of my cave. Upon my observing this, I laughed outright, and said, 'Try if thou canst find anything by night where I have failed by daylight.' The person himself could not help laughing, too; and then he went away. [Source: Eliade Page]

About a year after that, some hunters of Tsa, having failed to secure any game, happened to come strolling by the cave. As I was sitting in Samadhi, wearing the above triple-knotted apology for clothing, they prodded me with the ends of their bows, being curious to know whether I was a man or a bhuta. Seeing the state of my body and clothes, they were more inclined to believe me a bhuta. While they were discussing this amongst themselves, I opened my mouth and spoke, saying, 'Ye may be quite sure that I am a man.' They recognized me from seeing my teeth, and asked me whether I was Thopaga. On my answering in the affirmative, they asked me for a loan of some food, promising to repay it handsomely. They said, 'We heard that thou hadst come once to thy home many years ago. Hast thou been here all the while?' I replied, 'Yes; but I cannot offer you any food which ye would be able to eat.' They said that whatever did for me would do for them. Then I told them to make fire and boil nettles. They did so, but as they expected something to season the soup with, such as meat, bone, marrow, or fat, I said, 'If I had that, I should then have food with palatable qualities; but I have not had that for years. Apply the nettles in place of the seasoning.' Then they asked for flour or grain to thicken the soup with. I told them if I had that, I should then have food with sustaining properties; but that I had done without that for some years, and told them to apply nettle tips instead. At last they asked for some salt, to which I again said that salt would have imparted taste to my food; but I had done without that also for years, and recommended the addition of more nettle tips in place of salt. They said, 'Living upon such food, and wearing such garments as thou hast on now, it is no wonder that thy body hath been reduced to this miserable plight. Thine appearance becometh not a man. Why, even if thou should serve as a servant, thou wouldst have a bellyful of food and warm clothing. Thou art the most pitiable and miserable person in the whole world.' I said, 'O my friends, do not say that. I am one of the most fortunate and best amongst all who have obtained the human life. I have met with Marpa the Translator, of Lhobrak, and obtained from him the Truth which conferreth Buddhahood in one lifetime; and now, having entirely given up all worldly thoughts, I am passing my life in strict asceticism and devotion in these solitudes, far away from human habitations. I am obtaining that which will avail me in Eternity. By denying myself the trivial pleasures to be derived from food, clothing, and fame, I am subduing the Enemy [Ignorance] in this very lifetime. Amongst the World's entire human population I am one of the most courageous, with the highest aspirations . . . .

I then sang to them a song about my Five Comforts:

'Lord! Gracious Marpa! I bow down at Thy Feet!

Enable me to give up worldly aims.

'Here is the Draghar-Taso's Middle Cave,

On this the topmost summit of the Middle Cave,

1, the Yogi Tibetan called Repa,

Relinquishing all thoughts of what to eat or wear, and this life's aims,

Have settled down to win the perfect Buddhahood.

'Comfortable is the hard mattress beneath me;

Comfortable is the Nepalese cotton-padded quilt above me.

Comfortable is the single meditation-band which holdeth up my knee,

Comfortable is the body, to a diet temperate inured,

Comfortable is the Lucid Mind which discerneth present clingings and

the Final Goal;

Nought is there uncomfortable; everything is comfortable.

'If all of ye can do so, try to imitate me;

But if inspired ye be not with the aim of the ascetic life,

And to the error of the Ego Doctrine will hold fast,

I pray that ye spare me your misplaced pity;

For I a Yogi am, upon the Path of the Acquirement of Eternal Bliss.

'The Sun's last rays are passing o'er the mountain tops;

Return ye to your own abodes.

And as for me, who soon must die, uncertain of the hour of death,

With self-set task of winning perfect Buddhahood,'

No time have I to waste on useless talk;

Therefore shall I into the State Quiescent of Samadhi enter now.'

[Translation by W. Y. Evans-Wentz and Lama Kazi Dawa-Samdup, in Evans-Wentz, Tibet's Great Yogi Milarepa (Oxford, 1928), pp. 199-202

History of Buddhist Sects

Songsten

The Nyingma Order traces it origins to Guru Rinpoche, an Indian sage who arrived in Tibet in the 8th or 9th century, and King Songtsen Gampo (630-649), who helped to establish Buddhism in Tibet (See Above). In the 11th century Tibetan Buddhism became stronger and more politicized. The power of the ruling monks increased and the religion splintered into several sects. This period was marked by fierce rivalry between sects: first between the Kagyupa order established by Milarepa (1040-1123) and the Sakyapa order which emerged in 1073 from the Sakya monastery, a monastery funded by the Kon family, and later between Yellow, Red and Black Hat sects.

According to the Encyclopedia of Buddhism: “By the twelfth century, small lineages began developing into specific orders that compiled the writings of exemplary figures. The initial cloisters were expanded, becoming "mother" monasteries for a series of satellite temples and monasteries. Orders established dominion in their areas, so that lay practice tended to come under the aegis of important teachers. Buddhist doctrinal and philosophical material became an important part of the curriculum. Translation activity continued, but with an emphasis on the revision of previous translations. A canon of translated scripture and exegesis was compiled throughout this period, so that by the end of the fourteenth century its major outlines became relatively clear. Finally, the aura of the emerging orders attracted the interest of Central Asian potentates, beginning with the Tanguts and extending to the grandsons of Genghis Khan. [Source: Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Gale Group Inc., 2004]

“The Nyingma (“Old School”) order had coalesced around the received teachings derived from the Royal dynastic period, whether transmitted in a human succession or as revealed treasure teachings. Preeminently, Vimalamitra and Padmasambhava (Guru Rinpoche) among the Indians, and Vairotsana among the Tibetans, were the mythic sources for treasure scriptures. The important treasure finder Nyangrel Nyima Özer (1142–1192) and his school in southern Tibet promoted Padmasambhava over other figures. From Nyangel’s group came the vehicle for the spread of the cult of Avalokiteśvara as the special protector of Tibet, purportedly embodied in Emperor Songtsen gampo. The Tibetan Book of the Dead also has its origins in these movements

“However, many original Tibetan contributions to Buddhism also came from this period. Among his innovations, Chokyi Sengge (1109–1169) developed philosophical definitions, doctrines of universals, and methods of argumentation; many challenged Indian assumptions. These doctrines posited a single meditative method under the rubric of the Great Seal and proposed that all the Buddha's statements were of definitive meaning.

Drogön Chogyal Phagpa (1235–1280), the fifth leader of the Sakya school of Tibetan Buddhism, proclaimed Kublai Khan's national preceptor in 1261. Sakya leaders supported Mongol policies, such as the first census of Tibet, and some scholars became influenced by Mongol and Chinese literature. Later, “Moreover, the peculiarly Tibetan office of the reincarnate lama became institutionalized. While earlier teachers were said to be the reembodiment of specific saints or bodhisattvas, this was the first formalization of reincarnation, with the previous saint's disciples maintaining continuity and instructing his reembodiment.

In the 13th century, with the help of Mongolian supporters, the Sakya sect took control of much of Tibet. The Mongols under Genghis Khan had raided Tibet but converted to Tibetan Buddhism after a meeting between Genghis Khan’s grandson, Kokonor, and the head of the Sakya monastery. Sakya rule lasted for about 100 years. Three secular dynasties — the Phgmogru, the Ripung and the Tsangpa — followed between the years 1354 and 1642, when the Yellow Hat (Gelugpa) sect emerged as the dominant order.

Tsongkhapa

Tsongkhapa, whose ordained name was Losang Dragpa, was a famous teacher of Tibetan Buddhism and the founder of Gelugpa School of Tibetan Buddhism. His name means “The Man from Onion Valley” in Tibetan. Tsongkhapa was born into a nomadic family in Amdo Tibetan area in 1357. Today the location of Tsongkhapa's birth is marked by Kumbum Monastery. Tsongkhapa was a great 14th century Tibetan Buddhist Master who promoted and developed the Kadampa Buddhism that Atisha had introduced three centuries earlier. His appearance in Tibet had been predicted by Buddha himself.

As a great teacher of Tibetan Buddhism, Tsongkhapa patiently taught the Tibetans everything they needed for their spiritual development, from the initial step of entering into a spiritual practice through to the ultimate attainment of Buddhahood. His followers became known as the ‘New Kadampas’, and to this day Kadampa Buddhists worldwide study his teachings and strive to emulate his pure example.

According to the Encyclopedia of Buddhism: Born in Amdo, Tsongkhapa ((1357–1419) originally studied in many traditions, but his most important intellectual influence was the Sakya monk Rendawa Zhonnu Lodro (1349–1412). Tsongkhapa became dissatisfied with the contemporary understanding of monastic institutions and more general aspects of scholarship. With successive visions of Mañjuśrī,Tsongkhapa understood that he was to emphasize the system that Atisha had brought to Tibet. Eventually, after many years of wandering through Tibet bestowing instruction, he was persuaded to settle down and in 1409 founded the Ganden monastery and established the Geluk (Virtuous Order, Yellow Hats) school. [Source: Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Gale Group Inc., 2004]

. “In a series of important treatises, he articulated a systematization of the exoteric Mahayana meditative path and the esoteric practice according to the Vajrayana. In the latter instance, he employed interpretive systems developed by exponents of ta tantra to articulate a systematic hermeneutics that could be applied to all tantras. Tsongkhapa, though, is best noted for his intellectual synthesis of the Madhyamaka and Yogacara systems of Buddhism, using Indian treatises as a basis for his great commentaries and subcommentaries, and emphasizing the philosophical position of Chandrakirti. |~|

Dalai Lamas

First Dalai Lama

There have been 14 Dalai Lamas. The first, a nephew of Tsongkhapa, the founder of Tibetan Buddhism, was born in 1351 and was a shepherd. The title of Dalai was first bestowed on the 3rd Dalai Lama by a Mongol chief named Altan Khan when the Dalai Lama visited the court of the Mongol Khans in the 16th century. The 3rd Dalai Lama became the spiritual leader for Mongolia as he was in Tibet. He ordered that the image of Gonggor be worhsipped at home and issued laws forbidding the practice killing women, slaves and animals as sacrificial funeral offerings. The 5th Dalai Lama is credited with uniting the warlike medieval tribes of Tibet. In 1642, he became the political and spiritual leader of all Tibet.

As has been the case with kings and world leaders, there have been good Dalai Lamas and bad ones and ones whose lives have ended in tragedy. Many died young , including the 9th, 10th, 11th and 12th Dalai Lamas. Some were rumored to have been poisoned. Others were believed to have been murdered. Only half of the men who held the title have lived to see their thirties. At least four are believed to have been killed amid palace intrigue. In 1682, a government minister hid the death of the Dalai Lama for fifteen years, secretly ruling with the help of a look-alike.

One of the worst was the 6th Dalai Lama who was more interested in women and alcohol than he was in studying and leading. He used to sneak out of Potala in disguise to visit local brothels. A Jesuit monk who lived Lhasa as the time of his leadership wrote that “no good-looking person of either sex was safe from his unbridled licentiousness.” His ineptitude gave China an excuse to intercede in Tibetan affairs.

The 13th Dalai Lama barely escaped an assassination attempt allegedly orchestrated by his own regent. He recognized Tibet’s backwardness made it vulnerable to aggression by more advanced nations of the world. His plans to improve and reform the Tibetan bureaucracy and military were thwarted by the monastic elite.

Yellow Hat Sect and the Fifth Dalai Lama

Third Dalai Lama

The Yellow Hats (Gelupa) emerged in the 15th century. Founded by Tsongkhapa (See Above), they were given a big boost in the 16th century when the Mongols decided to support them. The sect became preeminent in the middle of the 17th century, through the efforts of Mongolian supporters and Tibetan supporters inspired by the charismatic 5th Dalai Lama. The Yellow Hats took control of the central plateau and maintained control until British and Chinese incursions into Tibet in 19th century.

The 5th Dalai Lama, Ngawang Lobsang Gyatso (1617-82) is regarded as the greatest of the Dalai Lamas. Born in Chongye in the Yarlung Valley, he unified Tibet and set the precedent for future Dalai Lamas. He was the first Dalai Lama to exercise temporal power and ruled benevolently as both a spiritual and political leader and initiated construction of the Potala palace. In paintings he wears a yellow hat and holds a thunderbolt in his right hand and a bell in his left hand. He is sometimes shown holding a lotus flower, a Wheel of Law or another sacred object.

The fifth Dalai Lama is credited with unifying central Tibet after a protracted era of civil wars. As an independent head of state, he established diplomatic relations with China and also met with early European explorers. He was the first Dalai Lama to become spiritual and political leader of Tibet and the greatest of all the Dalai Lamas.

Image Sources: Purdue University, Kalachakranet.org

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2024