TIBETAN BUDDHIST PRAYER FLAGS

Prayer flags

Prayer flags are colored pieces of cloth that have Buddhist sutras printed on them. They are strung up at mountain passes and along trails and streams and are attached to chortens, temples and other sacred structures so their prayers can be released in the wind to purify the air and appease the gods. When the flags flutter in the wind, Tibet Buddhists believe the sutras on them are released to heaven and this bring merit to the people who tied them. The tradition of tying prayer flags evolved out of worship for the God of Soil, and important Bon deity in Tibet before the arrival of Buddhism.

Tibetan prayer flags are inscribed with auspicious symbols, invocations, prayers, and mantras. The Tibetan word for prayer flag is Dar Cho. “Dar” means to increase life, fortune, health and wealth. “Cho” means all sentient beings. Prayer flags are simple devices that, coupled with the natural energy of the wind, quietly harmonize the environment, impartially increasing happiness and good fortune among all living beings. [Sources: Timothy Clark, Radiant Heart Studio; Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

The prayer flag tradition is ancient, dating back thousands of years to ancient Buddhist India and to the shamanistic Bon tradition of pre-Buddhist Tibet. There were similar traditions in ancient Persia and China. Bonpo priests used solid colored cloth flags, perhaps with their magical symbols, to balance the elements both internally and externally. Buddhists added their own texts to increase the power of the flags.

There is a legend about the creation of prayer flag: Once a monk obtained an important scripture from India, but unfortunately while he was returning back home, the scripture got wet in a river. Having laid the scripture open to dry in the sunshine, the monk then sat and meditated with his legs crossed under a big tree. Suddenly, gongs and horns rang out and the sound of Sanskrit reverberated in the air. As the gentle breeze was stroking his face under the blue sky, the monk felt utterly refreshed and all of a sudden, seemed to understand everything in the universe completely. Slightly opening his eyes, the monk found the scripture had been blown all over the sky, the tree, and the river. He let out a loud laugh and disappeared in the distance, leaving behind the flying scripture and the bursts of the sound of Sanskrit. From then on, the Tibetans began to print lines of the scripture on cloth orpaperand hang them in the air in commemoration of the monk's attained enlightenment and as a tribute to the Buddhist scripture. [Source: chinaculture.org, Chinadaily.com.cn, Ministry of Culture, P.R.China]

See Separate Articles: TIBETAN BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN BUDDHIST OBJECTS: MANI STONES, PRAYER WHEELS AND HUMAN BONES factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN BUDDHIST RITUALS, CUSTOMS AND PRAYERS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Tibetan Ritual” by Jose Ignacio Cabezon Amazon.com; “Tibetan Rituals of Death” by Margaret Gouin Amazon.com; Buddhist Ritual Art of Tibet: A Handbook on Ceremonial Objects and Ritual Furnishings in the Tibetan Temple Amazon.com; Magic and Mystery in Tibet: Discovering the Spiritual Beliefs, Traditions and Customs of the Tibetan Buddhist Lamas - An Autobiography” by Alexandra David-Neel and A. D'Arsonval (1931) Amazon.com; “The Little Book of Tibetan Rites and Rituals: Simple Practices for Rejuvenating the Mind, Body, and Spirit” by Judy Tsuei Amazon.com; Symbols: “The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs” by Robert Beer Amazon.com; “The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols” by Robert Beer Amazon.com; “Buddhist Symbols in Tibetan Culture : An Investigation of the Nine Best-Known Groups of Symbols” by Dagyab Rinpoche and Robert A. F. Thurman Amazon.com; Tibetan Buddhism: “Essential Tibetan Buddhism” by Robert A. F. Thurman Amazon.com; “Initiations and Initiates in Tibet” by Alexandra David-Neel Amazon.com; “The Secret Oral Teachings in Tibetan Buddhist Sects” by Alexandra David-Neel, Lama Yongden Amazon.com; Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism by John Powers Amazon.com; “The World of Tibetan Buddhism: An Overview of Its Philosophy and Practice” by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Geshe Thupten Jinpa Amazon.com; “Tibetan Buddhism: With its Mystic Cults, Symbolism and Mythology, and in Its Relation to Indian Buddhism” by L Austine Waddell Amazon.com; “The Jewel Tree of Tibet: The Enlightenment of Tibetan Buddhism” by Robert Thurman and Sounds True Amazon.com; “A Concise Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism” by John Powers Amazon.com; “The Preliminary Practices of Tibetan Buddhism” by Geshe Rapten Amazon.com; “Teachings and Practice of Tibetan Tantra” Amazon.com; “Tantra in Practice” by David Gordon White Amazon.com

Meaning of Prayer Flags

Prayer flags contain ancient symbols, prayers and mantras for generating compassion, health, wish fulfillment, and for overcoming diseases, natural disasters and other obstacles. In this present dark-age disharmony reigns and the elements are way out of balance. The earth needs healing like never before. Prayer flags moving in the wind generate a natural positive energy. Acting on a spiritual level the emanating vibrations protect from harm and bring harmony to everything touched by the wind.

Prayer flags are said to bring happiness, long life and prosperity to the flag planter and those in the vicinity. Early Tibetan people plant prayer flags to honor the nature gods of Bon. They hung the flags outside their homes, over mountain passes and rivers and places of spiritual significance for the wind to carry the beneficent vibrations across the countryside. When Buddhism was introduced to Tibet in the 7th century, it absorbed many Bon traditions, including the flags The early Buddhist flags contained both Buddhist prayers and pictures of the fierce Bon gods who they believed protected Buddha. Over the next 200 years Buddhist monks began to print mantras and symbols on the flags as blessings to be sent out to the world with each breeze. Thus they became known Prayer Flags.

Dharma prints on the prayer flags bear traditional Buddhist symbols, protectors and enlightened beings. As the Buddhist spiritual approach is non-theistic, the elements of Tantric iconography do not stand for external beings, but represent aspects of enlightened mind i.e. compassion, perfect action, fearlessness, etc. Displayed with respect, Dharma prints impart a feeling of harmony and bring to mind the precious teachings.

Prayer flags can have different meanings depending on the occasion. Hanging them on birthdays and festive days is believed to be capable of bringing auspicious and peaceful blessings to heaven, the earth, human beings, and livestock. Herdsmen fasten prayer flags in the hope of being blessed when moving from one place to another. Pilgrims cross the desert with prayer flags on their shoulders hoping for a safe and problem-free trip. People living by a lake or river place prayer flags along the water's edge to show their reverence for the god of water while those living among mountains and forests suspend prayer flags to fulfill their obligations to the god of mountains. [Source: chinaculture.org, Chinadaily.com.cn, Ministry of Culture, P.R.China]

When a Living Buddha passes away, it is a rare and grand occasion. People express their condolences and respect for the Buddha by hanging prayer flags on the roof of every home. As an important folk cultural art form with a religious theme, prayer flags have gained their unique characteristics in the course of their development. Like many other folk arts in Tibet, such as fresco painting,thangka(religious painting on scrolls), and Tibetan sculpture, prayer flags are another exotic flower in the folk art of the Tibetan holy land.

See Separate Articles: HISTORY OF TIBETAN BUDDHISM Factsanddetails.com/China ; articles about TIBETAN BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com

History of Tibetan Prayer Flags

According to some lamas prayer flags date back thousands of years to the Bon tradition of preBuddhist Tibet. Shamanistic Bonpo priests used primary colored plain cloth flags in healing ceremonies. Each color corresponded to a different primary element - earth, water, fire, air and space – the fundamental building blocks of both our physical bodies and of our environment. According to Eastern medicine health and harmony are produced through the balance of the 5 elements. Properly arranging colored flags around a sick patient harmonized the elements in his body helping to produce a state of physical and mental health. Colored flags were also used to help appease the local gods and spirits of the mountains, valleys, lakes and streams. These elemental beings, when provoked were thought to cause natural disasters and disease. Balancing the outer elements and propitiating the elemental spirits with rituals and offerings was the Bonpo way of pacifying nature and invoking the blessings of the gods. [Source: Timothy Clark, Radiant Heart Studio =]

It is not known whether or not the Bonpos ever wrote words on their flags. The preBuddhist religions of Tibet were oral traditions; writing was apparently limited to government bookkeeping. On the other hand the very word, “bonpo,” means “one who recites magical formulas” Even if no writing was added to the plain strips of cloth it is likely that the Bonpos painted sacred symbols on them. Some symbols seen on Buddhist prayer flags today undoubtedly have Bonpo origins, their meaning now enhanced with the deep significance of Vajrayana Buddhist philosophy. =

From the first millennium AD Buddhism gradually assimilated into the Tibetan way of life reaching great zeal in the ninth century when the religious King of Tibet invited the powerful Indian meditation master, Guru Padmasambhava, to come and control the forces then impeding the spread of Buddhism. Guru Rinpoche, as he is popularly known, bound the local Tibetan spirits by oath and transformed them into forces compatible with the spread of Buddhism. Some to the prayers seen on flags today were composed by Guru Rinpoche to pacify the spirits that cause disease and natural disasters. =

Originally the writing and images on prayer flags were painted by hand, one at a time. Woodblocks, carefully carved in mirror image relief, were introduced from China in the 15th century. This invention made it possible to reproduce identical prints of the same design. Traditional designs could then be easily passed down from generation to generation. =

Famous Buddhist masters created most prayer flag designs. Lay craftsmen make copies of the designs but would never think of actually creating a new design. There are relatively few basic designs for a continuous tradition that goes back over a thousand years. Aside from new designs no real innovations to the printing process have occurred in the past 500 years. =

When the Chinese took over Tibet they destroyed much of everything having to do with Tibetan culture and religion. Prayer flags were discouraged but not entirely eliminated. We will never know how many traditional designs have been lost forever since the turmoil of China’s cultural revolution. Because cloth and paper prints deteriorate so quickly the best way to preserve the ancient designs is by saving the woodblocks. Woodblocks, often weighing several pounds, were too heavy for the refugees to lug over the Himalayas and woodblocks no doubt made wonderful firewood for Chinese troops. Most of the traditional prayer flags today are made in Nepal and India by Tibetan refugees or by Nepali Buddhists from the Tibetan border regions.

Prayer Flags Colors and Designs

The five colors of prayer flags represent the five basic elements: yellow — earth; green — water, red — fire, white — air, blue — space. Balancing these elements externally brings harmony to the environment. Balancing the elements internally brings health to the body and the mind. [Source: chinaculture.org, Chinadaily.com.cn, Ministry of Culture, P.R.China]

In the eyes of the Tibetans, white is the color of purity and kindness; red means prosperity and toughness; green shows serenity and gentleness; yellow indicates mercy and talent; and blue reveals intelligence and bravery. Five colors are the subject of a folk songs: " Yellow flags are the symbol of the lotus flower / Red ones signal timely wind and rain / Blue ones represent thriving and prosperous descendants / Red ones on grass land looks like antlers, shining like dazzling sunlight while burning vigorously like a fireball on top of a roof."

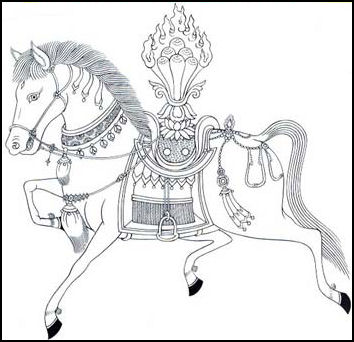

The design of a prayer flag consists of two parts: the picture and the scripture. A typical prayer flag has a horse bearing three flaming jewels — symbolizing the Buddha, Buddhist teachings, and the Buddhist community — on the back of its center. At each corner of the flag there is a god of protection, believed to be capable of eliminating bad luck. These gods are represented by the symbols of the garuda (a mythical eagle), the penetratingdragon, the watchfultiger, and the triumphant lion.

Scattered among the images are a few lines of scripture, serving as a foil to the picture and forming a pleasant contrast. The combination of the symbols represents the five elements in the universe, signifying their circulation and the eternity of life. Besides these images, Buddha and Buddhist scriptures are also employed.

The combination of the pictures and the scripture is usually well spaced, with a conspicuous theme. The picture, the colors, and the scripture tend to have deep connotations and symbolic meaning. According to the Bon religious doctrine, the five animals on the prayer flags represents five parts of the human body: The central horse is the symbol of the human soul as well as good luck; the garuda is the animal of the life force; the tiger symbolizes the human body; the dragon indicates prosperity while the lion refers to destiny.

The scripture on the flags often focuses on Indian Bhadrani incantations and the six-word mystic teaching of the truth (Om-ma-ni, pad-me-Hum). In some cases, the first word "Om" is engraved on the belly of the horse.

Texts on Tibetan Prayer Flags

Early in the 7th Century the Tibetan King Song Tsen Gompo sent his minister to India to learn Sanskrit and writing. The Tibetan script we see today on prayer flags was modeled after an Indian script used at that time. Texts seen on prayer flags can be broadly categorized as mantra, sutra and prayers. [Source: Timothy Clark, Radiant Heart Studio =]

A mantra is a power-laden syllable or series of syllables or sounds with the capacity of influencing certain energy dimensions. The vibration of mantra can control the invisible energies and occult forces that govern existence. Continuous repetition of mantras is practiced as a form of meditation in many Buddhist schools. Mantras are almost always in Sanskrit – the ancient language of Hinduism and Buddhism. They range in length from a single “seed syllable” like OM to long mantras such as the “Hundred-syllable mantra of Vajrasattva.” They are not really translatable; their inner meanings are beyond words. Probably the oldest Buddhist mantra and still the most widespread among Tibetans is the six-syllable mantra of Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion. OM MANI PADME HUNG! Printed on prayer flags the mantra sends blessings of compassion to the six worldly realms.=

Sutras are prose texts based on the discourses directly derived from Shakyamuni Buddha, the historical Buddha who taught in India 2500 years ago. Many sutras have long, medium and short versions. Prayer flags use the medium or short versions. One short form of sutra often seen on prayer flag is the dharani. Closely related to mantras, dharanis contain magical formulas comprised of syllables with symbolic content. They can convey the essence of a teaching or a particular state of mind. The Victory Banner (Gyaltsen Semo) contains many lines of dharani. Praise to the 21 Taras, the Long Life Flag and the White Umbrella are also examples of prayer flags using Sutras. For purposes of categorization all the other text seen on prayer flags can fall under the general term “prayers.” These would include supplications, aspirations and good wishes written by various masters throughout the history of Mahayana Buddhism. =

Symbols on Tibetan Prayer Flags

Wind horse

Symbols by definition have meanings larger than their mere appearance. In the case of sacred Buddhist symbols the meanings are often hinting at vast notions beyond words. Long treatises have been written on the meanings of such symbols. Listed below are brief meaning of some of the more common symbols. [Source: Timothy Clark, Radiant Heart Studio =]

The Wind Horse (Lung-ta) carrying the “Wish Fulfilling Jewel of Enlightenment” is the most prevalent symbol used on prayer flags. It represents good fortune; the uplifting life force energies and opportunities that makes things go well. When one’s lung-ta is low obstacles constantly arise. When lung-ta is high good opportunities abound. Raising Wind Horse prayer flags is one of the best ways to raise one’s lung-ta energy. =

The Eight Auspicious Symbols (Tashi Targye) is one of the most popular symbol groupings among Tibetans and also one of the oldest, being mentioned in the Pali and Sanskrit canonical texts of Indian Buddhism. These Eight Symbols of Good Fortune are: 1) The Parasol- which protects from all evil The Golden Fish – representing happiness and beings saved from the sea of suffering; 2) The Treasure Vase – sign of fulfillment of spiritual and material wishes; 3) The Lotus- symbol of purity and spiritual unfoldment; 4) The Conch Shell –proclaims the teachings of the enlightened ones; 5) The Endless Knot- symbolizing meditative mind and infinite knowledge of the Buddha; 6) The Victory Banner – symbolizes the victory of wisdom over ignorance and the overcoming of obstacles; 7) The Dharma Wheel – symbol of spiritual and universal law; 8) The Vajra (Tibetan: dorje) is the symbol of indestructibility. In Buddhism it represents true reality, the being or essence of everything existing. This pure emptiness is unborn, imperishable and unceasing. =

The Four Dignities: These four animals—1) the Garuda, 2) the Sky Dragon, 3) the Snow Lion and 4) the Tiger— are seen in the corners of many Tibetan prayer flags – often accompanying the Wind Horse. They represent the qualities and attitudes necessarily developed on the spiritual path to enlightenment. These are qualities such as awareness, vast vision, confidence, joy, humility and power. =

The Seven Precious Possessions of a Monarch are: 1) Precious Wheel, 2) Precious Jewel, 3) Precious Queen, 4) Precious Minister, 5) Precious Elephant, 6) Precious Horse and 7) Precious General. These seven objects collectively symbolize secular power. They give the ruler knowledge, resources and power. In the Buddhist interpretation a comparison is drawn between the outward rule of the secular king and the spiritual power of a practitioner. To the spiritual practitioner the Seven Jewels represent boundless wisdom, inexhaustible spiritual resources and invincible power over all inner and outer obstacles. =

The Union of Opposites (mithun gyulgyal) is an interesting group of symbols. These mythological beings are joined rival pairs of animals created to symbolize harmony. A snow lion and a garuda, normally mortal enemies, were combined to form an animial with a snow lion’s body and a garuda’s head and wings. Likewise a fish was put together with an otter and a crocodile-like chu-srin was married to a conch shell. These composed creatures are often put on Victory Banners for the reconciliation of disharmony and disagreement. =

Deities and Enlightened Beings: Deities in Vajrayana Buddhism are not gods as such but representations of the aspects of Enlightened Mind. Their postures, hand gestures, implements and ornaments symbolize various qualities of the particular aspect. The three main aspects of enlightened mind are compassion, wisdom and power, represented respectively by Avalokiteshvara, Manjushri and Vajrapani. There are other images depicted on prayer flags that look very similar to the transcendental deities. These are actually enlightened human beings such as Shakyamuni Buddha, Guru Padmasambhava, and Milarepa. =

The Elements Vajrayana Buddhism divides the phenomenal and psycho-cosmic world into five basic energies. In our physical world these manifest as earth, water, fire, air and space. Our own bodies and everything else in the physical world is composed of these five basic elements. On a spiritual level these basic energies correspond to the 5 Buddha Families and the 5 Wisdoms. Prayer flags reflect this comprehensive system through color; each of the 5 colors relates to an element and an aspect of enlightened mind. It should be noted that there are two systems used so there is sometimes confusion about which color corresponds to which element. The order of the colors in prayer flag displays remains the same in both the systems. The color order is always: yellow, green, red, white and blue. In a vertical displays the yellow goes at the bottom and the blue at the top. For a horizontal display the order can go either from right to left or from left to right. =

According to the Nyingma School (Ancient Ones) the color element correspondence is: Blue – space White – air (sometimes referred to wind or cloud) Red – fire Green – water Yellow – earth The New Translation Schools switch the colors for air and water but keep the order of the colors the same. =

Wind Horse

The wind horse (“longa”) is the main symbol found on prayer flags. On his back the horse carries the Three Jewels of Buddhism — the Buddha, dharma, and sangha. The colors on prayer flags is highly symbolic. Red represents fire; green, wood; yellow, earth; blue, water; and white, iron.

The wind horse is an allegory for the human soul in the shamanistic tradition of East Asia and Central Asia. In Tibetan Buddhism, it was included as the pivotal element in the center of the four animals symbolizing the cardinal directions and a symbol of the idea of well-being or good fortune. It has also given the name to a type of prayer flag that has the five animals printed on it. Rlung rta, pronounced lungta is Tibetan for "wind horse." [Source: Wikipedia +]

In Tibet, a distinction was made between Buddhism and folk religion (usually a reference to Bon). Windhorse was predominantly a feature of the folk culture, a "mundane notion of the layman rather than a Buddhist religious ideal," as Tibetan scholar Samten G. Karmay explains.However, while "the original concept of rlung ta bears no relation to Buddhism," over the centuries it became more common for Buddhist elements to be incorporated.

Windhorse has several meanings in the Tibetan context. As Karmay notes, "the word [windhorse] is still and often mistakenly taken to mean only the actual flag planted on the roof of a house or on a high place near a village. In fact, it is a symbol of the idea of well-being or good fortune. This idea is clear in such expressions as rlung rta dar ba, the 'increase of the windhorse,' when things go well with someone; rlung rta rgud pa, the 'decline of windhorse,' when the opposite happens. The colloquial equivalent for this is lam ’gro, which also means luck."

In his 1998 study “The Arrow and the Spindle,” Karmay traces several antecedents for the wind horse tradition in Tibet. First, he notes that there has long been confusion over the spelling because the sound produced by the word can be spelt either klung rta "river horse" or rlung rta "wind horse". In the early twentieth century the great scholar Jamgon Ju Mipham Gyatso felt compelled to clarify that in his view rlung rta was preferable to klung rta, indicating that some degree of ambiguity must have persisted at least up to his time.

Karmay suggests that "river horse" was actually the original concept, as found in the Tibetan nag rtsis system of astrology imported from China. The nag rtsis system has four basic elements: srog "vital force", lus "body", dbang thang "field of power", and klung rta, "river horse". Karmey suggests that klung rta in turn derives from the Chinese idea of the lung ma, "dragon horse," because in Chinese mythology dragons often arise out of rivers (although 'brug is Tibetan for dragon, in some cases they would render the Chinese lung phonetically). Thus, in his proposed etymology the Chinese lung ma became klung rta which in turn became rlung rta. Samtay further reasons that the drift in understanding from "river horse" to "wind horse" would have been reinforced by associations in Tibet of the "ideal horse" (rta chogs) with swiftness and wind.

On prayer flags and paper prints, windhorses usually appear in the company of the four animals of the cardinal directions, which are "an integral part of the rlung ta composition": garuda or kyung, and dragon in the upper corners, and White Tiger and Snow Lion in the lower corners.[5] In this context, the wind horse is typically shown without wings, but carries the Three Jewels, or the wish fulfilling jewel. Its appearance is supposed to bring peace, wealth, and harmony. The ritual invocation of the wind horse usually happens in the morning and during the growing moon.

The windhorse ceremonies are usually conducted in conjunction with the lhasang ("smoke offering to the gods") ritual, in which juniper branches are burned to create thick and fragrant smoke. This is believed to increase the strength in the supplicator of the four nag rtsis elements mentioned above. Often the ritual is called the risang lungta, the "fumigation offering and (the throwing into the wind or planting) of the rlung ta high in the mountains." The ritual is traditionally "primarily a secular ritual" and "requires no presence of any special officiant whether public or private." The layperson entreats a mountain deity to "increase his fortune like the galloping of a horse and expand his prosperity like the boiling over of milk.

Types of Prayer Flags

Prayer flag types can be divided into about two-dozen categories; half a dozen of which comprise a large majority of the flags we see today. Wind Horse (Lung- ta) flags are by far the most common prayer flag, so much so that many people think that the word lung-ta means prayer flag. Their purpose is to raise the good fortune energy of the beings in the vicinity of the prayer flag. The wind horse, usually in pictorial form, always occupies the center of this flag. The outside corners of the flag is always guarded by the four great animals – the garuda, dragon, tiger and snow lion – either in pictorial form or in written word. The texts on the flags differ; usually a collection of various mantras or a short sutra. The Victory Banner Sutra (Gyaltsen Semo) is the most popular. [Source: Timothy Clark, Radiant Heart Studio =]

Victorious Banners are used to overcome obstacles and disturbances. Shakyamuni Buddha gave the Victory Banner Sutra to Indra, king of the god realm. Indra was instructed to repeat this sutra when going into battle in order to protect his troops and to assure victory over the demigods. The sutra has many protective dharanis to overcome obstacles, enemies, malicious forces, diseases and disturbances. Victory Banner flags display this sutra along with symbols such as the wind horse, the Eight Auspicious Symbols, the Seven Possessions of a Monarch and the Union of Opposites. Often there are special mantras added to increase harmony, health, wealth and good fortune. =

Health and Longevity Flags usually have a short version of the Buddha’s Long Life Sutra along with prayers and mantras for health and long life. Amitayus, the Buddha of Limitless Life is often in the center of the flag. Two other long life Deities, White Tara (peace and health) and Vijaya (victorious protection) are sometimes included. =

The Wish Fulfilling Prayer (Sampa Lhundrup) is a powerful protection prayer written by Guru Padmasambhava. It is said to be especially relevant to our modern age and is good for raising one’s fortune, protecting against war, famine, and natural disasters, as well as overcoming obstacles and quickly attaining ones wishes. These flags often have Guru Rinpoche in the center and repetitions of his powerful mantra OM AH HUNG VAJRA GURU PADMA SIDDHI HUNG. =

Praise to the 21 Taras was composed by the primordial Buddha Akshobhya. It was written into Sanskrit and Urdu by Vajrabushan Archarya and translated into Tibetan by Atisha in the 11th century. The first 21 Tara prayer flags are attributed to him. Tara was born from the compassionate tears of Avalokiteshvara. As he shed tears for the countless suffering beings one tear transformed into the Savioress Green Tara who then manifested her twenty other forms. The prayer to the 21 Taras praises all her manifestations. The flags with this prayer usually depict Green Tara in the center and often conclude with her root mantra OM TARE TUTARE TURE SOHA. The purpose of this flag is to spread compassionate blessings. =

Other prayer flag categories are too numerous to describe in this article but a few of the more popular designs are listed as follows: Avalokiteshvara – Bodhisattva of Compassion, The Warrior-King Gesar, The White Umbrella for Protection, the Kurukulle Power Flag, Manjushri- Embodiment of Wisdom, Milarepa – the Yogisaint, and the Vast Luck Flag. =

Different Styles of Prayer Flags

Designs on the prayer flags in Lhasa are more rigorous and magnificent, as well as more orthodox religiously and artistically, while those in eastern Tibet are more flexible in form and content. [Source: chinaculture.org, Chinadaily.com.cn, Ministry of Culture, P.R.China]

The style of wind horse flags varies a lot in different areas. In Lhasa, flags are made from small pieces of cloth and are hung on a thin rope, quite like the small colorful flags inBeijingthat welcome foreign heads of state. The Tibetans also like to draw a line of wind horse flags between two mountaintops or over the spacious streets of Lhasa.

In areas where the militant Kangba people live, the prayer flags look a little like the combat flags of ancient times. A mast with strips of cloth hanging from it is placed in the mountains. Sometimes, such masts can be seen over an area of about 600 square meters, and when looked at from a distance, resemble the red broomcorn plant.

Another type of prayer flag is made in the shape of a tower, with a piece of printed cloth wound layer on layer around a pillar, forming a Buddhist tower in the field and providing Tibetans with shade in the hot weather. The men in the shadow of a hanging prayer flag are said to have good luck.

Making Prayer Flags

The most commonly used material of prayer flags is cloth, but there are also flags made from hemp, silk, and handmade paper. Prayer flags come in various shapes and sizes, but in most cases, they are square or rectangular in shape and have a width ranging from 10 to 60 centimeters. Sometimes, a prayer flag can be as small as a narrow stripe while a large one can extend to cover a whole roll of cotton cloth.[Source: chinaculture.org, Chinadaily.com.cn, Ministry of Culture, P.R.China]

Most prayer flags are printed on polyester or nylon blends. Surprisingly, good quality cotton is hard to find in Nepal and India. Price differences for prayer flags are often due to the different qualities of cloth. Tibetans don’t mind the gauzy low thread count cloth (the wind passes through it easily). Synthetics vs. cotton is a matter of opinion. Some feel that polyester and nylon are more durable, some say they fade faster. Cotton colors tend to be richer and cotton threads are better for the environment.

Most prayer flags today are woodblock printed. Some shops are now starting to produce prints made from zinc faced blocks that can be etched photographically resulting in finer detail than the hand carved woodblock. Natural stone ground pigments have been replaced by printing inks, usually having a kerosene base. Most of the companies in the west prefer to use silkscreen printing techniques as wood carving is a time consuming skill requiring lengthy apprenticeship.

The process of making prayer flags is similar to that of making Tibetan scripture and wooden Buddhist carvings. First, painters and calligraphers are invited to paint images and write scripture on a piece of paper or a board, and then folk-carving craftsmen are asked to carve the pictures and scripture in detail onto a motherboard, which is then used to print the design on a piece of colorful cloth or paper. Harmonious spacing is important to the correct design of the wind-horse carving, as is the color contrast, the subtle combination of pictures and scriptures, and the vividness of the overall flavor and tone.

Raising Prayer Flags

Prayer flags are either attached to a rope or thrown out into the air at random. When the wild wind blows, pieces or clusters of prayer flags flutter against the blue sky, the snow mountains and the bright shining lakes, signaling the upward spirit and people's positive attitude toward life. The hanging of prayer flags is more flexible and is not confined to one pattern. The number 5 is important when hanging prayer flags.

Prayer flags typically come on ropes to be hung in horizontal displays or printed on long narrow strips of cloth that are tied on vertical poles. Prayer flags on ropes are printed on 5 different colors of cloth (yellow, green, red, white and blue) so sets are always in multiples of 5. Pole flags are either a single solid color or the 5 colors sewn together into one flag. They range in height from about 3ft to 40 ft or more. Pole flags often have colored streamers or “tongues” that are imprinted with special increasing mantras meant to increase the power of the prayers written on the body of the flag. It is also common to see displays of many plain white prayer flags on poles erected around monasteries and pilgrimage sites. [Source: Timothy Clark, Radiant Heart Studio =]

Generally speaking, there are five hanging patterns. 1) The first and the most common pattern is to arrange the flags in the shape of the Chinese character " " (meaning "one"). 2) The second is to attach a flag to a mast measuring ten-odd meters in height. 3) Next comes the particularly beautiful "tower pattern" in which the flags are hung around a pillar in the shape of anumbrella, forming a hollow tower. 4) The "encircling pattern" is most often seen aroundBuddhist pagodas, or pagoda groups. 5) Another pattern is the so-called "embattling pattern", well known for its large scale and intense patterns. Prayer flags arranged in this pattern are reputed to be the most spectacular land art in the world. [Source: chinaculture.org, Chinadaily.com.cn, Ministry of Culture, P.R.China]

By placing prayer flags outdoors their sacred mantras are imprinted on the wind, generating peace and good wishes. Ropes of prayer flags can be strung horizontally between two trees (the higher the better), between house columns or along the eaves of roofs. Sometimes they are strung at angle (be sure that the wind horse points uphill). When raising prayer flags proper motivation is important. If they are put up with the attitude “I will benefit from doing this” – that is an ego-centered motivation and the benefits will be small and narrow. If the attitude is “May all beings everywhere receive benefit and find happiness,” the virtue generated by such motivation greatly increases the power of the prayers. Tibetan tradition considers prayer flags to be holy. Because of they contain sacred texts and symbols they should be treated respectfully. They should not be placed on the ground or put in the trash. When disposing of old prayer flags the traditional way is to burn them so that the smoke may carry their blessings to the heavens. =

Image Sources:

Text Sources: 1) “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China”, edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K.Hall & Company, 1994); 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China ethnic-china.com *\; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2022