EARLY TIBETAN HISTORY

Dzong palace

First palace Yumbu Yakhar

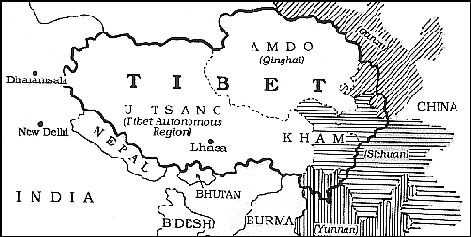

founded in 200 BC according to legendTibetans are considered a Central Asian ethnic group. They live primarily on the high Tibetan plateau, in the western Sichuan and Yunnan mountains of central and southern China, and areas throughout the Himalayas and around the Tibetan plateau. Tibet has traditionally been divided into three parts with the central part roughly coinciding with today’s Tibet Autonomous Region.

The word Tibet, which first appeared on maps of Arabic explorers, is believed to either be derived from the Tibetan term for “upper Tibet,” stod bod, or from the early Indian name for Tibet, bhot. The Chinese term for Tibetans is Bhotia. Tibetans refer themselves by the place-names of their geographical areas or tribal name such of the Golock people of Amdo or the Ladakis and Zanskaris from northern India.

Tsetang, Tibet’s third largest city, is the mythical birthplace of the Tibetan people. According to legend a monkey mediating in a cave was seduced by a female demon who had refused to wed another monster. She married the monkey and produced six children who grew up to form the six major tribes of Tibet. Another myth describes how the first Tibetan king descended to earth from heaven on a sky rope. These myth are believed to have their origin in the ancient Bon religion.

Throughout most of their history Tibetans have been left primarily to themselves. The rugged terrain that occupied and surrounded their homeland discouraged invaders.

See Separate Articles Under the heading TIBETAN HISTORY factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources on Tibet: Central Tibetan Administration (Tibetan government in Exile) www.tibet.com ; Chinese Government Tibet website eng.tibet.cn/; Wikipedia article on Tibet Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on Tibetan History Wikipedia ; Tibetan News site phayul.com ; Snow Lion Publications (books on Tibet) snowlionpub.com ; Tibetan Cultural Sites: Tibetan Cultural Region Directory kotan.org ; White Paper on Tibetan Culture english.people.com.cn ; Tibet Activist Groups: Free Tibet freetibet.org ; Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy tchrd.org ; Students for a Free Tibet studentsforafreetibet.org ; Students for a Free Tibet UK /sftuk.org ; Friends of Tibet friendsoftibet.org ; Campaign for Tibet (Save Tibet) savetibet.org ; Tibet Society tibetsociety.com ; Tibetan Studies and Tibet Research: Tibetan Resources on The Web (Columbia University C.V. Starr East Asian Library ) columbia.edu ; Tibetan and Himalayan Libray thlib.org Digital Himalaya ; digitalhimalaya.com ; Tibetan Studies Maps WWW Virtual Library ciolek.com/WWWVL-TibetanStudies ; Center for Research of Tibet case.edu ; Tibetan Studies resources blog tibetan-studies-resources.blogspot.com ; News, Electronic Journals ciolek.com/WWWVLPages ; Book: "Tibetan Civilization" by Rolf Alfred Stein. Robert Thurman, a friend of the Dalai Lama and professor of Indo-Tibetan studies at Columbia University, is regarded the preeminent scholar on Tibet in the United States.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: The Dawn of Tibet: The Ancient Civilization on the Roof of the World by John Vincent Bellezza Amazon.com; “Secrets of Ancient Tibet, 6,000 B.C.” by M.G. Hawking, J. Wolfe Ph.D., et al Amazon.com; “A History of Zhang Zhung and Tibet, Volume One: The Early Period” by Chogyal Namkhai Norbu, Donatella Rossi , et al Amazon.com; “The Light of Kailash Vol 2" by Choegyal Namkhai Norbu (Author), Donatella Rossi Amazon.com; “The Light of Kailash. A History of Zhang Zhung and Tibet: Volume Three. Later Period: Tibet” by Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, Nancy Simmons, et al. Amazon.com; “Ancient Tibet” by Tarthang Tulku Amazon.com; General History: “Tibet: A History” by Sam van Schaik Amazon.com; “A Historical Atlas of Tibet” by Karl E. Ryavec Amazon.com; “Histories of Tibet” by Kurtis R. Schaeffer , William A. McGrath, Amazon.com; “Himalaya: A Human History” by Ed Douglas, James Cameron Stewart, et al. Amazon.com; “Tibet & Its History” by Hugh Richardson (1989) Amazon.com; "Tibetan Civilization" by Rolf Alfred Stein Amazon.com; “The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama” by Thomas Laird Amazon.com

Ancient Tibetans

The Tibetans first settled along the middle reaches of the Yarlung Zangbo River (Brahmaputra River) in Tibet. Evidence of the new and old stone age culture was found in archaeological excavations at Nyalam, Nagqu, Nyingchi and Qamdo. According to ancient historical documents, members of the earliest clans formed tribes known as "Bos" (or “Pos”) in the Shannan area—Lhoka, located on the middle and lower reaches of the Yarlung Valley in southern Tibet near the present-day border with Bhutan. [Source: China.org china.org ]

The Tibetans first settled along the middle reaches of the Yarlung Zangbo River (Brahmaputra River) in Tibet. Evidence of the new and old stone age culture was found in archaeological excavations at Nyalam, Nagqu, Nyingchi and Qamdo. According to ancient historical documents, members of the earliest clans formed tribes known as "Bos" (or “Pos”) in the Shannan area—Lhoka, located on the middle and lower reaches of the Yarlung Valley in southern Tibet near the present-day border with Bhutan. [Source: China.org china.org ]

Tibetans are believed to have evolved from the Qiang, one of the first ethnic groups to be referred to in Chinese historical records. They were mentioned in the 12th century B.C. by members of the Chinese Zhou dynasty, who originated from the western plains near the mountains in Gansu where the Qiang lived. The Zhou identified the Qiang as allies and the two groups were very similar and may have exchanged women. In the 6th century B.C. as the Zhou and Chinese became increasingly involved in intensive agriculture the Qiang began migrating towards their present homeland in Sichuan. There were reports of Qiang states in the A.D. 4th and 5th centuries, around the time the first Tibetan kingdoms were reported.

In southern Tibet, Tibetan kingdoms began to develop as early as A.D. 400, according to some sources. The oldest extant example of Tibetan writing, which dates from around A.D. 767, indicates the presence in this region of a settled kingdom. Ancient Tibetans were a fierce, war-like, horse people with a reputation not unlike that of the Mongol Hordes of Genghis Khan. During the Ming dynasty Tibetans used to sell the Chinese around 30,000 horses a year.+

It is said that the ancient were ruled by 12 petty cheiftans. In 237 B.C., there was great discontent and fighting since they had no overall leader. One day, a dozen Tibetan priests came across a strange young man, and they declared him a godafter they asked him who he was, and he answered that he was a "mighty one." When they asked where he had come from he pointed to India across the mountains, but the priests thought he was pointing to the heavens. The priests thought him to the "son of the God," and seated him on a "chair" held up by the necks of four men. The priests declared, "We shall make him our lord," and so he was known as "the neck chair, mighty one" and was the first king of all Tibet. [Source: chinaculture.org, Chinadaily.com.cn, Ministry of Culture, P.R.China]

There is another tale that has been handed down for the ages: A woman in Boyu (today's Bomi) area had nine children. The youngest son was not a normal child, for he was born with turquoise eyebrows, overhanging eyelids, and his fingers were webbed. The family was most distressed and frightened by the child. They wanted to be rid of the boy so they placed him in a lead box and threw it into the river Ganges. The boy, however, did not die, and was found by a peasant. When the man opened the box, he discovered the strange child and was filled with much love for him and took him home to live as one of his family. So the boy spent a happy childhood, loved and cared for by the peasant and his wife.

See Separate Article TIBETAN PEOPLE: HISTORY, POPULATION AND CHARACTERISTICS factsanddetails.com ; Also See Origin of the Qiang and Qiang migrations Under QIANG MINORITY factsanddetails.com

Zhangzhung Kingdom

Zhangzhung (Zhang Zhung, Xiangxiong or Shangshung) was an ancient culture and kingdom of western and northwestern Tibet, which pre-dates the culture of Tibetan Buddhism in Tibet. Zhangzhung culture is associated with the Bon religion, which in turn, has influenced the philosophies and practices of Tibetan Buddhism. Zhangzhung people are mentioned frequently in ancient Tibetan texts as the original rulers of central and western Tibet. Only in the last two decades have archaeologists been given access to do archaeological work in the areas once ruled by the Zhangzhung.

The Zhangzhung Kingdom was the earliest civilization center on the Tibetan plateau. Zhangzhung means "land of the roc” in Tibetan. Roc is a huge mythical bird. According to historical records, before the rise of the Tubo Kingdom (629-846), the Zhangzhung Kingdom existed and flourished in western Tibet, living mainly on animal husbandry, with some agriculture. The kingdom even established ties with the Tang Dynasty in China's Central Plains. [Source: chinaculture.org, Chinadaily.com.cn, Ministry of Culture, P.R.China]

The kingdom of Guge and Tibet (Tubo) are associated with the Zhangzhung. According to Namkhai Norbu some Tibetan historical texts identify the Zhang Zhung culture as a people who migrated from the Amdo region into what is now the region of Guge in western Tibet. Zhang Zhung is considered to be the original home of the Bön religion. By the 1st century BC, a neighboring kingdom arose in the Yarlung Valley, and the Yarlung king, Drigum Tsenpo, attempted to remove the influence of the Zhang Zhung by expelling the Zhang's Bön priests from Yarlung. He was assassinated and Zhang Zhung continued its dominance of the region until it was annexed by Songtsen Gampo in the 7th century. Recently, a tentative match has also been proposed between the Zhangzhung and an Iron Age culture now being uncovered on the Changtang plateau in northwestern Tibet. [Source: Wikipedia +]

See Zhangzhung Kingdom Under Separate Article NORTHERN TIBET factsanddetails.com

Tibetans in the A.D. 3th to 6th Century

Trade between Tibet has Central Asian increased around A.D. 250. Bronze and iron objects, and ritual or status objects, made their to Tibet beginning around then. From A.D. 350, a wave of Eurasian immigrants reached Tibet, bringing with them warrior-related technology and horse gear.

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: Around 2,000 years ago Tibetans fell into two sub-groups, the Qiang and the Ti. Both names appeared repeatedly as political conceptions, but the Tibetans, like all other state-forming groups of peoples, sheltered in their realms countless alien elements. In the course of the third and second centuries B.C. the group of the Ti, mainly living in the territory of the present Sichuan, had mixed extensively with remains of the Yue-chih; the others, the Qiang, were northern Tibetans or so-called Tanguts; that is to say, they contained Turkish and Mongol elements. In A.D. 296 there began a great rising of the Ti, whose leader Ch'i Wan-nien took on the title emperor. The Qiang rose with them, but it was not until later, from 312, that they pursued an independent policy. The Ti State, however, though it had a second emperor, very soon lost importance, so that we shall be occupied solely with the Qiang. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“As the tribal structure of Tibetan groups was always weak and as leadership developed among them only in times of war, their states always show a military rather than a tribal structure, and the continuation of these states depended strongly upon the personal qualities of their leaders. Incidentally, Tibetans fundamentally were sheep-breeders and not horse-breeders and, therefore, they always showed inclination to incorporate infantry into their armies. Thus, Tibetan states differed strongly from the aristocratically organized "Turkish" states as well as from the tribal, non-aristocratic "Mongol" states of that period.

“The empire of the Tibetans was organized quite differently from the empires of the Huns and the Xianbei tribes. The Tibetan organization was purely military and had nothing to do with tribal structure. This had its advantages, for the leader of such a formation had no need to take account of tribal chieftains; he was answerable to no one and possessed considerable personal power. Nor was there any need for him to be of noble rank or descended from an old family. The Tibetan ruler Fu Chien (A.D. r. 357-385) organized all his troops, including the non-Tibetans, on this system, without regard to tribal membership.

From 650 onward the Tibetans gained immensely in power, and pushed from the south into the Tarim basin. In 678 they inflicted a heavy defeat on the Chinese, and it cost the Tang decades of diplomatic effort before they attained, in 699, their aim of breaking up the Tibetans' realm and destroying their power.

Ancient Cliff Caves in Mustang

Mustang, a former kingdom in north-central Nepal just south of the Tibet border, is home to caves carved int the sides of cliffs with human remains that are thousands of years old. Michael Finkel wrote in National Geographic: It “is home to one of the world’s great archaeological mysteries. In this dusty, wind-savaged place, hidden within the Himalaya and deeply cleaved by the Kali Gandaki River—in spots, the gorge dwarfs Arizona’s Grand Canyon—there are an extraordinary number of human-built caves. Some sit by themselves, a single open mouth on a vast corrugated face of weathered rock. Others are in groups, a grand chorus of holes, occasionally stacked eight or nine stories high, an entire vertical neighborhood. Some were dug into cliffsides, others tunneled from above. Many are thousands of years old. The total number of caves in Mustang, conservatively estimated, is 10,000. [Source: Michael Finkel, National Geographic, October 2012 -]

The caves were painstakingly hand-dug from the brittle stone. “No one knows who dug them. Or why. Or even how people climbed into them. (Ropes? Scaffolding? Carved steps? Nearly all evidence has been erased.) In the mid-1990s, archaeologists from the University of Cologne and Nepal began peeking into some of the more accessible caves. They found several dozen bodies, all at least 2,000 years old, aligned on wooden beds and decorated with copper jewelry and glass beads, products not locally manufactured, reflecting Mustang’s status as a trade thoroughfare. -

“Pete Athans first glimpsed the caves of Mustang while trekking in 1981. Many of the caves appear impossible to reach—you’d have to be a bird, it seems, to gain entry—and Athans, an exceptionally accomplished alpinist was stirred by the challenge they presented. During visits between 2007 and 2011 Athans and his team had made some sensational finds. In one cave they discovered a 26-foot-long mural with 42 exquisitely rendered portraits of great yogis in Buddhist history. In another was a trove of 8,000 calligraphed manuscripts—a collection, most of it 600 years old, that included everything from philosophical musings to a treatise on mediating disputes. The most promising site was a cave complex near a tiny village called Samdzong, just south of the Chinese border. Athans and Mark Aldenderfer of the University of California, Merced; had visited Samdzong in 2010 and found a system of funerary caves. At least some were created by tunneling down from slopes above the cliffs. To access some mortuary caves narrow shafts were excavated. When the cliff face collapsed the tombs were exposed.

History of the Cliff-Side Caves in Mustang

Michael Finkel wrote in National Geographic: “Early Mustang, it’s thought, was ruled by powerful kings....Seven hundred years ago, Mustang was a bustling place: a center of Buddhist scholarship and art, and possibly the easiest connection between the salt deposits of Tibet and the cities of the Indian subcontinent. Salt was then one of the world’s most valuable commodities. In Mustang’s heyday, says Charles Ramble, an anthropologist at the Sorbonne in Paris, caravans would move across the region’s rugged trails, carting loads of salt. [Source: Michael Finkel, National Geographic, October 2012-]

“Later, in the 17th century, nearby kingdoms began dominating Mustang, says Ramble. An economic decline set in. Cheaper salt became available from India. The great statues and brilliantly painted mandalas in Mustang’s temples started crumbling. And soon the region was all but forgotten, lost beyond the great mountains. -

“Aldenderfer divides cave use in Mustang into three general periods. First, as long as 3,000 years ago, the caves were burial chambers. Then, around 1,000 years ago, they became primarily living quarters. Within a few centuries, the Kali Gandaki Valley—the neck in the hourglass connecting Asia’s highlands and lowlands—may have been frequently battled over. “People were scared,” Aldenderfer says. Families, placing safety over convenience, moved into the caves. Finally, by the 1400s, most people had moved into traditional villages. The caves were still used—as meditation chambers, military lookouts, or storage units. Some caves remained homes, and even today a few families live in them. “It’s warmer in winter,” says Yandu Bista, who was born in 1959 in a Mustang cave and resided in one until 2011. “But water is difficult to haul up.” -

What Athans and the scientists wanted most was a cave with items from before the era of written records to shed light on the deepest mysteries: Who first lived in the caves? Where did these people come from? What did they believe? Most of the caves Athans had peeked into were empty, though they showed signs of domestic habitation: hearths, grain-storage bins, sleeping spaces.

Tombs in the Ancient Cliff Caves in Mustang

On a cave later named Tomb 5, Michael Finkel wrote in National Geographic: “Athans, dangling on the green rope, maneuvered nimbly into the smallest cave. He had to crouch to get in—it was only five feet high and roughly six feet wide and six feet deep. This cave, it was clear, was once a hidden shaft tomb, or mortuary cave, dug in the shape of a wine decanter. When it was excavated, only the very top of the shaft was visible. Bodies were lowered down the sewer-pipe-size shaft, and the hole was backfilled with rock. When the cliff face collapsed, the entire cave was exposed, creating a cross-sectional view. [Source: Michael Finkel, National Geographic, October 2012-]

“A large boulder, once part of the ceiling, had landed on the cave’s floor. If there was anything in the cave, it was beneath that rock. Athans tugged at it, levering it gradually toward the cave’s mouth. Then he shouted, “Rock!” and the boulder thundered down the wall, kicking up a cloud of amber dust. Fifteen centuries or so after it was sealed, as carbon dating later proved, the cave was once again clear of debris. The first thing Athans found in the closet-size chamber—later designated Tomb 5—was wood, superb dark hardwood, cut into various planks and slats and pegs. Aldenderfer and Mohan Singh Lama of Nepal’s Department of Archaeology eventually fitted the pieces together, creating a box about three feet tall: a coffin. It was ingeniously constructed so that the sections fit through the tomb’s narrow entrance and then could easily be assembled in the main chamber.” Painted on the box, in orange and white pigments, was a rudimentary but unmistakable image: a person riding a horse. “Probably his favorite horse,” Aldenderfer guessed. Later, as if to confirm the man’s status as an equine aficionado, a horse skull was found in the cave. -

“On the 2010 trip to Samdzong, in the two biggest caves on the cliff wall, the team had located human remains from 27 individuals, including men, women, and one child. There were bedlike or rudimentary coffins in those caves as well, but they were made of much inferior wood and far simpler construction, with no paintings. Tomb 5, Aldenderfer theorized, was the burial plot of a high-ranking person, perhaps a local leader. The tomb, it turned out, held two bodies—an adult male and a child, maybe ten years old. The youth was a source of much speculation. “I don’t want to characterize the child as any kind of sacrifice or slave because I really don’t have a clue,” says Aldenderfer. “But a child in there does suggest a complex ritual.” -

Human Remains and Artifacts in the Mustang Cliff-Side Caves

Mummies dating back to 2,000 years ago were wrapped in strips of cloth and placed in wooden coffins with copper bangles, glass bead and shell necklaces. Humans in some of the caves have numerous cut marks, evidence of defleshing before burial. It is possible this was an early version of Tibetan sky burials (the tradition in which bodies are consumed by vultures).

An adult in Tomb 5 in Samdzong was found with a gold-and-silver funerary mask with multicolored glass beads. He was probably a local leader who died 1,300 to 1,800 years ago. Signs of high status included iron daggers, a copper pot, sacrificed animals and a painting depicting a man, horses and trees. Among the other items found with the body were tsampa (ground barely flour), an iron tripod, wood and bamboo cups. The copper vessel may have been used to make chang, barely beer. Sacrificed animals included yaks, goats and horses. [Source: National Geographic]

Michael Finkel wrote in National Geographic: When Jacqueline Eng of Western Michigan University, “the team’s bone sleuth, took a close look at the remains, she made a startling discovery: The bones of 76 percent of all the individuals she examined bore the unmistakable scars of knife slices. These marks, says Eng, were clearly made after death. “This wasn’t hacking and whacking,” she says. The bones were relatively whole and lacked signs of deliberate breakage and burning. “All the evidence,” Eng notes, “indicates there was no cannibalism here.” [Source: Michael Finkel, National Geographic, October 2012-]

“The bones date from the third to the eighth centuries—before Buddhism came to Mustang—but the defleshing may be related to the Buddhist practice of sky burial. To this day, when a citizen of Mustang dies, the body may be sliced into small pieces, bones included. These are all swiftly snatched up by vultures. In the age of the Samdzong cave burials, Aldenderfer posits, the body was stripped of flesh but the bones were still articulated—“like a Halloween skeleton,” he says. The skeleton was lowered into the tomb and folded to fit in the wooden box. “Then whoever was down there with him,” says Aldenderfer, “climbed back out.” Before doing so, the ancient burial crew had made sure the corpse was regally adorned for the great beyond. As Athans hunched inside Tomb 5, sifting through dust for hour upon hour, he discovered these adornments. “It was so mesmerizing,” he says, “that I forgot to eat or drink.” -

“A trove of beads, the garment they’d been sewn on long disintegrated, was scooped up by Athans and placed in plastic sample bags. Singh Lama painstakingly sorted them. There were more than a thousand beads, made of glass, some as minuscule as poppy seeds, in a half dozen hues. As lab studies later showed, the beads were of various origins: some from what is now Pakistan, some from India, some from Iran. Three iron daggers, with gracefully curved hilts and heavy blades, also emerged. Then a bamboo teacup with delicate circular handle. A copper bangle. A small bronze mirror. A copper cooking pot and a ladle and a three-legged iron pot stand. Bits of fabric. A pair of yak or cow horns. An enormous copper cauldron, roomy enough to boil a beach ball. “I’m betting that’s a chang pot,” said Aldenderfer, referring to the regional beer made of fermented barley. -

Archaeology magazine reported in 206: In the Samdzong tomb complex in Upper Mustang, beside a gold and silver funerary mask, were several textiles that are the subject of a new analysis. They include separate pieces made of wool and horsehair, as well as silk, colored with a variety of organic dyes. Most intriguing was that silk wasn’t produced locally at the time, around 1,500 years ago, which suggests that the area was not isolated as once thought, but had connections with the Silk Road, and that locals ably combined local products with imports from India and China. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2016]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Purdue University, University of Washington

Text Sources: 1) "Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China", edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K.Hall & Company, 1994); 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China *\; 4) Chinatravel.com; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2022