UYGHURS AND CHINESE

Uyghurs and Chinese seem to have deeply rooted antipathy for one another. Theroux wrote: the Uyghurs ‘seemed totally out of sympathy with the Chinese, and often mocked them. Their world was entirely separate: it was Allah, and the central Asian steppes, a culture of donkey carts and dancing girls. They ate mutton and bread. They were people of the bazaar...Their Chinese was seldom fluent."Uyghurs are often the objects of discrimination. There are laws on the books that state that Uyghurs are not allowed to marry Han Chinese. Uyghur who travel outside of Xinjiang have a hard time finding work or even getting a room in a hostel. One Uyghur man who traveled to Shanghai told the New York Times, “As soon as they see I'm from Xinjiang, they tell me to go."

Uyghurs are sometimes afraid to speak their own language in front of Chinese and complain about the most mundane things out of fear of being labeled a separatist or terrorist. One Uyghur man told the New Yorker that the Chinese never fight fair: “It’s not because of their culture, and it’s not because of their history. It comes from something inside their blood.”

Beijing, stresses ethnic harmony in the region and says the government has helped improve living standards and developed its economy. Many Uyghurs believe it is good to go along with th government and make economic gains rather than engage in political activities that will be quickly put down, achieve little and put their participants in jail. They don’t particularly like Communist Chinese rule but they see a Uyghur homeland as a distance, unrealistic dream.

Some Uyghurs like their lifestyle in Beijing. They have Han Chinese friends and speak colloquial Mandarin. Joanne Smith, an Uyghur expert at Newcastle University, told the Los Angeles Times that the Uyghur are going through a ‘silent, pragmatic period.” On the subject of an independent Uyghur state, one Uyghur tour guide told the Los Angeles Times, “I’m not on favor it, nor do It think It’s possible. I don’t want to see Xinjiang become a second Iraq. And if Xinjiang became independent we’d lose access too China’s big market.”

There is minimal socializing between Chinese and Uyghurs. The two groups rarely go out at night together because many Uyghurs don’t drink or smoke. Intermarriage is rare. In many cases Chinese and Uyghurs in the same town won’t even use the same time (Chinese follow Beijing time while Uyghurs use local time). Mixed marriages between Uyghurs and Chinese are rare. It is not unusual for Han to comment about the “wanton sexuality of Uyghur girls” and then say “we’re civilizing them!”

See Separate Articles: Uyghurs and Xinjiang factsanddetails.com; UYGHURS AND THEIR HISTORY, LANGUAGE AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com; XINJIANG Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG EARLY HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG LATER HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/China

Websites and Sources: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Uyghur Photo site uyghur.50megs.com ; Uyghur News uyghurnews.com ; Uyghur Photos smugmug.com ;Islam.net Islam.net ; Uyghur Human Rights Groups ; World Uyghur Congress uyghurcongress.org ; Uyghur American Association uyghuramerican.org ; Uyghur Human Rights Project uhrp.org ; Uyghur Language Uyghur Written Language omniglot.com ; Xinjiang Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Muslims in China Islam in China islaminchina.wordpress.com ; Claude Pickens Collection harvard.edu/libraries ; Islam Awareness islamawareness.net ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Xinjiang History Book on the Great Game: “The Dust of Empire: The Race for Mastery in the Asian Heartland” by Karl E. Meyer (Century Foundation/Public Affairs, 2003). Uyghur and Xinjiang Experts: Dru Gladney of Pomona College; Nicolas Bequelin of Human Rights Watch; and James Miflor, a professor at Georgetown University. Henryk Szadziewski is the manager of the Uyghur Human Rights Project (www.uhrp.org). He lived in the People's Republic of China for five years, including a three-year period in Uyghur-populated regions. Henryk Szadziewski studied modern Chinese and Mongolian at the University of Leeds, and completed a master's degree at the University of Wales, where he specialized in Uyghur economic, social and cultural rights

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Uyghurs and China: “China and the Uyghurs” by Morris Rossabi Amazon.com; “Governing China's Multiethnic Frontiers” by Morris Rossabi Amazon.com “Uyghurs and China Internal Colonialism” by Christina J Ray Amazon.com; “Autonomy in Xinjiang: Han Nationalist Imperatives and Uyghur Discontent” by Gardner Bovingdon Amazon.com; About the Uyghurs and Their History: “The Uyghurs: Strangers in Their Own Land” by Gardner Bovingdon Amazon.com; “Soundscapes of Uyghur Islam” by Rachel Harris Amazon.com; “Language, Education and Uyghur Identity in Urban Xinjiang” by Joanne Smith Finley and Xiaowei Zang Amazon.com; “The Uyghur Language” by Gulis Aynur Derya Amazon.com; “A Brief Narrative of the Historical and Geographic Attributes of the Uyghur Identity: And Its Substantial Difference from the Turkic Identity and the Turkish Identity” by Mark Chuanhang Shan Amazon.com; “Situating the Uyghurs Between China and Central Asia” by Ildiko Beller-Hann, M. Cristina Cesàro, et al. Amazon.com; “The Sacred Routes of Uyghur History” by Rian Thum Amazon.com;

Uyghur Versus Chinese Numbers in Xinjiang

Xinjiang's population is now 46 percent Uyghur and 39 percent Han, official figures show, but many believe that real percentage of Uyghurs is lower and the percentage of Chinese is higher. When the Communist Party came to power in 1949, the Han proportion was less than seven percent, according to researchers.

Xinjiang is more than twice the size of Texas. The total population there is about 22 million. Han Chinese have been encouraged to migrate there. "If you look at the numbers, the percentage of the Uyghurs amongst the total population of Xinjiang is getting smaller," University of Hong Kong scholar Willy Lam told AFP. "So I think Beijing believes that at the end of the day the numbers are on their side." [Source: Kelly Olsen, AFP, July 3, 2013]

Uyghurs now make up only 12 percent of Urumqi’s population. [Source: Chris Walker and Morgan Hartley, The Atlantic, October 29, 2013]

Chinese and Uyghur Views of Each Other

Few Han Chinese bother to learn even the most basic words of the Uyghur language and are afraid to venture into Uyghur neighborhoods. Employees at Han-run hotels routinely tell customers, “Don’t go eat over there at night! Its full of Muslim people.” [Source: Los Angeles Times]

Many Chinese see the Uyghurs as they do Tibetans: lazy, backwards, ungrateful and given preferential treatments. One recently-arrived Chinese settler told the Los Angeles Times, “I’m really scared of the Uyghurs now. When I look into their eyes, I see wolves.”

An elderly Han woman running a minimart in Yarkand told the Los Angeles Times she was happy she had migrated from Shaanxi province to Xinjiang years ago, though she described her Uyghur customers as lazy and simple-minded. [Source: Julie Makinen, Los Angeles Times, October 26, 2014]

Nineteen-year-old Aike Ainivan, who works at a barbeque stand a Uyghur neighborhood in Kunming told Associated Press, "They call us Uyghur dogs, and say we are either pickpockets or drug dealers," he said.

Tensions Between Uighurs and Han Chinese

Ilham Tohti wrote: “As a Uyghur intellectual, I strongly sense that the great rift of distrust between the Uyghur and Han societies is getting worse each day, especially within the younger generation. Unemployment and discrimination along ethnic lines have caused widespread animosity. The discord did not explode and dissipate along with the July 5 incident and during subsequent social interactions. Instead, it has started to build up once again. The situation is getting gradually worse. Yet, fewer and fewer people dare to speak out. Since 1997, the primary government objective in the region has been to combat the “three evil forces”[terrorism, separatism and religious extremism]. Its indirect effect is that Uyghur cadres and intellectuals feel strongly distrusted and the political atmosphere is oppressive. [Source: Ilham Tohti, January 17, 2011, published in China Change, April 6, 2014 ~]

Rachel Lu wrote in Tea Leaf Nation: “In China’s urban areas, the relationship between Han, China’s predominant ethnic group, and Uyghurs — who are often migrants there eking out a living as street vendors or day laborers — can be quite contentious. Colored by poor personal experiences with vendors or pickpockets, many Han attach negative stereotypes to Uyghurs and bitterly complain about policies that they perceive to be favorable to minorities such as Uyghurs. [Source: Rachel Lu, Tea Leaf Nation, October 30, 2013 -]

“Some of those complaints have found their way online. In Dec. 2012, a tweet by a local police department in Hunan province went viral on China’s Internet because it reported a scuffle between Uyghur cake vendors and Han, which ended with the Uyghurs being compensated $25,000 for the destroyed cake. For Han Internet users who related stories of being forced to buy cake by Uyghur migrants, sometimes at knifepoint, the seemingly outrageous sum confirmed their long-held suspicion that Uyghurs receive preferential treatment because of their ethnic minority status. -

“Qin Ailing, a Chinese reporter who has written about Xinjiang, argued that personal relationships were the only way to change the dynamic. On Oct. 30, she tweeted that Chinese should “really pay attention to the Uyghur friends around you and the difficult predicaments that they’ve encountered in their lives — even those who may be preparing for ‘terrorist activities.’” -

Uyghur Medicine and Tourism

See Xinjiang

Uyghurs have their own form of traditional medicine, which is well-known in China. Uyghur medicine is dominated by a principal that dates back at least to ancient Greeks: the belief that world is composed of four elements: earth, water, fire and wind. Some people believe the Uyghurs founded acupuncture. Today teeth are pulled by sidewalk dentists at the local market and Xinjiang horses are sold for broken bones.

Reporting on the Chinese tourists in Kashgar, Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times, “They come for the camel rides, the chance to dress up like a conquering Qing dynasty soldier or to take selfies in front of one of the most historic Islamic shrines in Xinjiang. But the busloads of Chinese tourists who converge on the Afaq Khoja Mausoleum each day are mostly interested in a single raised crypt amid the dozens of tombs ensconced under the shrine’s soaring 17th-century dome. It is the one said to belong to Iparhan, a Uyghur imperial consort, who, according to legend, was so sweetly fragrant that she caught the attention of a Chinese emperor 2,700 miles away in Beijing — and was either invited to live with him or dragooned into the palace as a trophy of war. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, August 18, 2014]

Uyghur Economics

Uyghur have traditionally been herdsmen, oasis farmers and traders. Men have traditionally workers as farmers, traders and craftsmen while women were engaged in embroidery, making patterned felt and weaving rugs

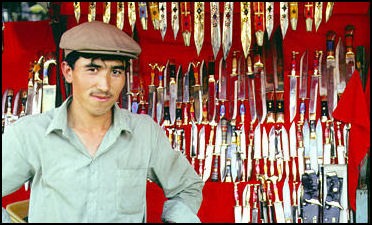

Yekshenbe Bazari (Sunday bazaar in Kashgar) is reputed to be the largest market in Central Asia. Sometimes covering almost a square mile, it is filled with tents and stalls, and 100,000 people buying and selling a wide assortment of stuff. The market is organized so that people selling the same kinds of things are grouped together. Among the items on sale are live chickens, caged songbirds, spices, tools, herbal medicines, colorful silk dresses, linen, parsnips, green peppers, scallions, tomatoes, sacks of grain, polished beans in a variety of shapes and colors, tools, gold necklaces, dyed silk clothes, dried reptile carcasses (used for medicine), multicolored piles of yarn, jeweled knives, firewood, boom boxes, camels, and snow leopard pelts. There are also sidewalk dentists, street barbers, donkey cart parking lots, bearded men in skullcaps and, tethered sheep, and merchants conducting horses auctions. Knife makers used old bicycles altered to spin grindstones to sharpen their knives.

In Old City neighborhoods Uyghurs ran shops out of storefronts attached to their homes. In recent years as the old neighborhoods have been demolished and Uyghurs have been forced into Chinese-style apartments on the outskirts of town, Uyghurs they have been unable to raise money and open new businesses.

The average income for rural families in Xinjiang (most Uyghurs live in villages) was $513 in 2008. The national average was $740, and $1,200 in Shanghai.

Many Uyghur regions are very poor. The average income in Qiongkuer Qiake is only $12 a month. One Uyghur student told the Washington Post, “We Uyghurs people are all farmers. The Han people are running all the businesses.” Some Uyghur merchants are prospering from trade with the Chinese.

Knowledge of Mandarin is a key to getting work, One 20-year-old university student told the Washington Post, “If I’m look for a job the first they want to know is what’s my Chinese level. and if it is not up to par, they say, “Go away.” State-owned enterprises are known for restricting Uyghur from growing facial hair or praying in the workplace, Uyghur say they are sometimes required to pay for heir jobs.

Many Uyghurs make their way to Beijing on the two-day train ride to make money and when they earn enough they return home on the two-day train ride back to Xinjiang. In Beijing, many Uyghurs run halal kebab restaurants. Others sell melons grown in oasis towns in Xinjiang or peddle fruitcakes from rickshaws.

In recent years Uyghurs have been recruited to work in factories in the industrialized southeastern coast of China, where they often endure discrimination and hostility from Han Chinese.

See Xinjiang Economics

Uyghur Traders

For centuries the Uyghurs were renowned as traders and money changers, skills which came in handy and enriched them in the Silk Road oasis towns they occupied.

For centuries the Uyghurs were renowned as traders and money changers, skills which came in handy and enriched them in the Silk Road oasis towns they occupied.

Uyghurs have been called “people of the bazaar.” Uyghur men are regarded throughout China as traders. They are found in almost every city. Some sell raisin, melons an occasionally hashish from Xinjiang. They have traditionally dominated the black market currency trade and buy and sell all manner of goods.

Many Uyghur traders can speak a half dozen languages, including Uyghurs, Chinese, Russian, Uzbek. Kazakh, Kyrgyz and Turkish. The traders don’t like to deal in foreign currencies. The profits margins are relatively small and there are chances of getting robbed or ripped off. They prefer wholesale clothing.

Describing one Uyghur trader, Peter Hessler wrote in New Yorker, “He had wavy back hair, flecked with white, and his eyes were brown and sad. He didn’t smile much. His skin was dark brown, and he had the solid jaw and prominent nose of a Middle Easterner. When he did smile, his face lit up. He often used the Chinese word jiade — fake — and he was deeply scornful of the products he sold. Trade was distasteful to him — he found it dishonest and cheap.”

Uyghur Agriculture

See Xinjiang

Uyghur Migrant Workers

As of 2009, about 1.5 million people from Xinjiang had migrated to more prosperous cities of coastal China.

The Uyghurs who worked at the Shaoguan toy factory that sparked the Urumqi riots all came from Shufu County outside Kashgar. In 2009, more than 6,700 young men and women left Shufu County, according to government figures, part of an ambitious jobs export program intended to relieve high youth unemployment and provide low-cost workers to factories. According to an article in the state-run Xinjiang Daily, 70 percent of the laborers had signed up for employment voluntarily. The article, published in May, did not explain what measures were used to win over the remaining 30 percent. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times July 16, 2009] Still, a few Uyghurs said they were thankful for factory jobs with wages as high as $190 a month, double the average income in Xinjiang. One man, a 54-year-old cotton farmer with two young daughters, said he was ready to send them away if that was what the Communist Party wanted. We would be happy to oblige, he said with a smile as his wife looked away. [Ibid]

Life of Uyghur Migrant Workers and Han Hostility

Once they arrive in one of China’s bustling manufacturing hubs, the Uyghurs often find life alienating. Li of China Labor Watch said many workers were unprepared for the grueling work, the cramped living conditions and what he described as verbal abuse from factory managers. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times July 16, 2009]

But the biggest challenge may be open hostility from Han co-workers, who like many Chinese hold unapologetically negative views of Uyghurs. Many Han say they believe that Uyghurs are given unfair advantages by the central government, including a point system that gives Uyghur students and other minorities a leg up on college entrance exams. [Ibid]

Zhang Qiang, a 20-year-old Shaoguan resident, described Uyghurs as barbarians and said they were easily provoked to violence. All the men carry knives, he said after dropping off a job application at the toy factory, which is eager to hire replacements for the hundreds of workers who quit in recent weeks. [Ibid]

Still, Zhang acknowledged that his contact with Uyghurs was superficial. When he was a student, his vocational high school had a program for 100 Xinjiang students, although they were relegated to separate classrooms and dorms. If he had any curiosity about his Uyghur classmates, it was quashed by a teacher who warned the Han students to keep their distance. This is not prejudice, he said. It is just the nature of their kind. [Ibid]

Resentment Over Uyghurs Being Forced Migrant for Work

Many Uyghurs are angry about plans to move them way to work, Residents in and around Kashgar say the families of those who refuse to go are threatened with fines that can equal up to six months of a villager’s income. If asked, most people will go, because no one can afford the penalty, said a man who gave his name only as Abdul, whose 18-year-old sister is being recruited for work at a factory in Guangzhou but has so far resisted. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times July 16, 2009]

Some families are particularly upset that recruitment drives are directed at young unmarried women, saying that the time spent living in a Han city far away from home taints their marriage prospects. Taheer, a 25-year-old bachelor who is seeking a wife, put it bluntly. I would not marry such a girl because there’s a chance she would not come back with her virginity, he said. [Ibid]

Heyrat Niyaz, an Uyghur journalist and blogger, told Hong Kong newsweekly Yazhou Zhoukan: “In the eyes of [Uyghur] nationalists you can joke all you like, but don't joke about our women. Almost all of the workers initially organized to be sent out to work were 17- and 18-year-old girls. At the time, some elders said, ‘sixty percent of these girls will wind up as prostitutes; the other forty percent will marry Han Chinese.” This led to enormous disgust [among people]. In carrying out this policy, the government first failed to carry out proper education work and, second, failed to realize that such a small thing could have such major repercussions.” [Source: Hong Kong newsweekly Yazhou Zhoukan interview of Heyrat Niyaz, an Uyghur journalist, blogger, and AIDS activist , siweiluozi.blogspot.com ]

Resentment Over Uyghurs Being Forced Migrant for Work

Many Uyghurs are angry about plans to move them way to work, Residents in and around Kashgar say the families of those who refuse to go are threatened with fines that can equal up to six months of a villager’s income. If asked, most people will go, because no one can afford the penalty, said a man who gave his name only as Abdul, whose 18-year-old sister is being recruited for work at a factory in Guangzhou but has so far resisted. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times July 16, 2009]

Some families are particularly upset that recruitment drives are directed at young unmarried women, saying that the time spent living in a Han city far away from home taints their marriage prospects. Taheer, a 25-year-old bachelor who is seeking a wife, put it bluntly. I would not marry such a girl because there’s a chance she would not come back with her virginity, he said. [Ibid]

Heyrat Niyaz, an Uyghur journalist and blogger, told Hong Kong newsweekly Yazhou Zhoukan: “In the eyes of [Uyghur] nationalists you can joke all you like, but don't joke about our women. Almost all of the workers initially organized to be sent out to work were 17- and 18-year-old girls. At the time, some elders said, ‘sixty percent of these girls will wind up as prostitutes; the other forty percent will marry Han Chinese.” This led to enormous disgust [among people]. In carrying out this policy, the government first failed to carry out proper education work and, second, failed to realize that such a small thing could have such major repercussions.” [Source: Hong Kong newsweekly Yazhou Zhoukan interview of Heyrat Niyaz, an Uyghur journalist, blogger, and AIDS activist , siweiluozi.blogspot.com ]

Image Sources: Uyghur image website; All Empires com; Silk Road Foundation; Mongabey; CNTO; Guicida Birmezir

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2015