EARLY XINJIANG HISTORY

Xinjiang is as much part of Central Asia as it is of China. Central Asia has a rich history with more than its share of conquests and invasions. It was lively commercial center that lay at the axis of the Silk Road trade between Asia and Europe. It was also a major a center of education, art, architecture, religion, poetry and science.

Xinjiang is as much part of Central Asia as it is of China. Central Asia has a rich history with more than its share of conquests and invasions. It was lively commercial center that lay at the axis of the Silk Road trade between Asia and Europe. It was also a major a center of education, art, architecture, religion, poetry and science.

Christopher Bodeen of Associated Press wrote: “The arid Central Asian region has for centuries occupied a position along the Chinese geographic and cultural periphery and was not under Chinese control for much of that time. The ancient "Silk Road" ran through the region, making it a key route for trade and the transmission of foreign concepts such as Buddhism. [Source: Christopher Bodeen, Associated Press, May 22, 2014]

Xinjiang has a documented history that goes back 2,500 years and has been controlled by a succession of peoples and empires, who have dominated all or parts of its territory. Among the groups and powers that have ruled or controlled all or parts of Xinjiang (from oldest to newest) are the Tocharians, Yuezhi, Xiongnu Empire, Xianbei state, Kushan Empire, Rouran Khaganate, Han Empire, Former Liang, Former Qin, Later Liang, Western Liáng, Rouran Khaganate, Tang Dynasty (618-906), Tibetan Empire, Uyghur Khaganate, Kara-Khitan Khanate, Mongol Empire, Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368), Chagatai Khanate, Moghulistan, Northern Yuan,Yarkent Khanate, Dzungar Khanate, Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), the Republic of China and, since 1950, the People's Republic of China.

The first settlers, the Tocharians, were herders who spoke an Indo-European language and appear to have worshiped cows. Victor H. Mair, a professor of Chinese language and literature at the University of Pennsylvania, told the New York Times, “I say the Tarim Basin was one of the last parts of the earth to be occupied. It was bound by mountains. They couldn’t live there until they had certain irrigation technologies.”The British historian Arnold Toynbee described Central Asia as a "roundabout" where routes covered "from all quarters of the compass and from which routes radiate out to all quarters of the compass again." Influence ove the region has come from Siberia, Mongolia, China, Persia, Turkey and Russia.

Crossroads of history has been used to describe a lot of places but nowhere is it more apt than in Central Asia. So many groups — a lot of the with names Westerners are unfamiliar with — came, inhabited, passed through, settled, conquered, left and stayed, and it is hard to keep track of them all. They came from all directions, and represented many different religions and ethnic groups from both Europe and Asia.

See Separate Articles: Uyghurs and Xinjiang factsanddetails.com; TARIM MUMMIES IN XINJIANG (WESTERN CHINA) factsanddetails.com ; UYGHURS AND THEIR HISTORY, LANGUAGE AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com; XINJIANG Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG EARLY HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG LATER HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/China

Websites and Sources: Xinjiang Wikipedia Article Wikipedia Xinjiang Photos Synaptic Synaptic ; Maps of Xinjiang: chinamaps.org Uyghur Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Uyghur Photo site uyghur.50megs.com ; Uyghur News uyghurnews.com ; Uyghur Photos smugmug.com ;Islam.net Islam.net ; Uyghur Human Rights Groups ; World Uyghur Congress uyghurcongress.org ; Uyghur American Association uyghuramerican.org ; Uyghur Human Rights Project uhrp.org ; Uyghur Language Uyghur Written Language omniglot.com ; Uyghur and Xinjiang Experts: Dru Gladney of Pomona College; Nicolas Bequelin of Human Rights Watch; and James Miflor, a professor at Georgetown University. Henryk Szadziewski is the manager of the Uyghur Human Rights Project (www.uhrp.org). He lived in the People's Republic of China for five years, including a three-year period in Uyghur-populated regions. Henryk Szadziewski studied modern Chinese and Mongolian at the University of Leeds, and completed a master's degree at the University of Wales, where he specialized in Uyghur economic, social and cultural rights. Tourist Office: Xinjiang Tourism Administration, 16 South Hetan Rd, 830002 Urumqi, Xinjiang China, tel. (0)- 991-282-7912, fax: (0)- 991-282-4449

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Xinjiang: China's Central Asia” by Jeremy Tredinnick Amazon.com; “Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang” by James Millward Amazon.com; “The Cultures of Ancient Xinjiang, Western China: Crossroads of the Silk Roads” by Alison Betts, Marika Vicziany, et al. Amazon.com; “The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West” by Victor H. Mair and J. P. Mallory Amazon.com; “The Mummies of Urumchi” by Elizabeth Wayland Barber Amazon.com; “A History of Russia, Central Asia and Mongolia, Volume II: Inner Eurasia from the Mongol Empire to Today, 1260 - 2000" by David Christian Amazon.com; “Land of Strangers: The Civilizing Project in Qing Central Asia” by Eric Schluessel Amazon.com; “The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia” by Peter Hopkirk Amazon.com

Lifestyle of Ancient People of Western China

Tarim mummy The oldest mummies found in Xinjiang, were probably Tocharians, herders who traveled eastward across the Central Asian steppes and whose language belonged to the Indo-European family. The mummies at the Niya site probably belonged to the Afanasievo or later Andronova cultures of the Russian steppes. The ancient cities of Niya and Loulan thrived around the rivers and lakes of Tarim basis in the Taklimakan desert and died out when the water sources dried up. A second wave of migrants came from what is now Iran.

Some settlers in Xinjiang may have come from as far away as Europe. A mummy from the Lop Nur area, the 2,000-year-old Yingpan Man, was unearthed wearing a hemp death mask with gold foil and a red robe decorated with naked angelic figures and antelopes — all hallmarks of a Hellenistic civilization.

The people who lived in western China 3,000 years ago were farmers and animal herders. They ate stewed mutton cooked over an open fire and round bread similar to what people in western China eat today. The early inhabitants of Niya lived in homes built of stones, mud bricks or reeds and posts, with fireplaces, stucco walls with floral designs.

Excavated temples were painted with sun symbols that seem to indicate that they worshiped Mithra, an Indo-Iranian god. Wood carving and furniture had depictions of elephants and mythical beasts found in Greek and Roman art and the art of other cultures. Hundreds of wooden documents" were inscribed with Kharosshthi script, an Indian alphabet of Aramaic origin dating back to the fifth century B.C., and used to record Silk Road transactions. [Source: Thomas B. Allen, National Geographic, March 1996]

2,500-Year-Old Noodles, Cakes and Porridge Found in Xinjiang

In 2010, Jennifer Viegas wrote in Discovery News, “noodles, cakes, porridge, and meat bones dating to around 2,500 years ago were unearthed at a Chinese cemetery, according to a paper that appeared in the Journal of Archaeological Science. Since the cakes were cooked in an oven-like hearth, the findings suggest that the Chinese may have been among the world's first bakers. Prior research determined the ancient Egyptians were also baking bread at around the same time, but this latest discovery indicates that individuals in northern China were skillful bakers who likely learned baking and other more complex cooking techniques much earlier. [Source: Jennifer Viegas, Discovery News, November 19, 2010]

"With the use of fire and grindstones, large amounts of cereals were consumed and transformed into staple foods," lead author Yiwen Gong and his team wrote in the paper. Gong, a researcher at the Graduate University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, and his team dug up the foods at the Subeixi Cemeteries in the arid Turpan region of Xinjiang. "As a result, the climate is so dry that many mummies and plant remains have been well preserved without decaying," according to the scientists, who added that the human remains they unearthed at the site looked more European than Asian. [Ibid]

“The individuals may have been living in a semi agricultural, pastoral artists' community, since a pottery workshop was found nearby, and each person was buried with pottery,” Viegas wrote. “The archaeologists also found bows, arrows, saddles, leather chest-protectors, boots, woodenwares, knives, an iron aw, a leather scabbard, and a sweater in the graves. But the scientists focused this particular study on the excavated food, included noodles mounded in an earthenware bowl.” “The noodles were thin, delicate, more than 19.7 inches in length and yellow in color," according to Lu and his colleagues. "They resemble the La-Mian noodle, a traditional Chinese noodle that is made by repeatedly pulling and stretching the dough by hand." [Ibid]

The food also included ‘sheep's heads (which may have held symbolic meaning), another earthenware bowl full of porridge, and elliptical-shaped cakes as well as round baked goods that resembled modern Chinese moon cakes. Chemical analysis of the starches revealed that both the noodles and cakes were made of common millet. The scientists next put new millet through a barrage of cooking experiments to see if they could duplicate the micro-structure of the ancient foods, which would then reveal how the prehistoric chefs cooked the millet. The researchers determined that boiling damages the appearance of individual millet grains, while baking leaves them more intact. The scientists therefore believe the millet grains in one bowl were once boiled into porridge, the noodles were boiled, and the cakes were baked.” [Ibid]

"Baking technology was not a traditional cooking method in the ancient Chinese cuisine, and has been seldom reported to date," according to the authors, who nevertheless believe these latest food discoveries indicate baking must have been a widespread cooking practice in northwest China 2,500 years ago. [Ibid]

“The discoveries add to the growing body of evidence that millet was the grain of choice for this part of China. Houyuan Lu of the Chinese Academy of Sciences' Institute of Geology and Physics, along with other researchers, unearthed millet-made noodles dating to 4,000 years ago at the Laija archaeological site, also in northwest China. Gong and his team point out that millet was domesticated about 10,000 years ago in northwest China and was probably a food staple because of its drought resistance and ability to grow in poor soils. [Ibid]

World's Oldest Pornography in Xinjiang

Goldilocks, Tarim mummy

The world's oldest pornography is found among 5,500-year-old petroglyphs in Xinjiang in western China. Mary Mycio wrote in Slate.com, “The Kangjiashimenji Petroglyphs are bas-relief carvings in a massive red-basalt outcropping in the remote Xinjiang region of northwest China. The artwork includes the earliest—and some of the most graphic—depictions of copulation in the world. Chinese archeologist Wang Binghua discovered the petroglyphs in the late 1980s, and Jeannine Davis-Kimball, an expert on Eurasian nomads, was the first Westerner to see them. Though she wrote about the carvings in scholarly journals , they remain obscure. “The cast of 100 figures presents what is obviously a fertility ritual (or several). They range in size from more than nine feet tall to just a few inches. All perform the same ceremonial pose, holding their arms out and bent at the elbows. The right hand points up and the left hand points down, possibly to indicate earth and sky. [Source: Mary Mycio, Slate.com, February 14, 2013]

“The few scholars who have studied the petroglyphs think that the larger-than-life hourglass figures that begin the tableau symbolize females. They have stylized triangular torsos, shapely hips and legs, and they wear conical headdresses with wispy decorations. Male images are smaller triangles with stick legs and bare heads. Ithyphallic is archeology-talk for “erect penis,” and nearly all of the males have one. A third set of figures appear to be bisexual. Combining elements of males and females, they are ithyphallic but wear female headwear, a decoration on the chest, and sometimes a mask. They might be shamans.

“The tableau is divided into four fully-developed scenes beginning at a height of 30 feet and progressing downward. In the first scene, nine huge women and two much smaller men dance in a circle, seemingly admonishing their viewers. This is the only scene without ithyphallic men—though to the side, a prone bisexual has an obvious erection. Two symbols near the center look like stallions fighting head to head.

“The second scene is packed with weird happenings. Women and men dance in a frenzy around a large ithyphallic bisexual about to penetrate a small hourglass female with an explicit vulva. His breastplate depicts a female head, with a conical headdress just like his. On the left, a second bisexual in a monkey mask is about to penetrate a small, faceless female. Nearby, a pair of striped animals lies prone amid bows and arrows, while at the other end, a giant two-headed female seems to lead the ritual. Disembodied heads abound, perhaps indicating spectators.

“The next scene is smaller and cruder. A chorus line of infants emerges from a small female being penetrated simultaneously by a male and a bisexual while three more ithyphallic males await their turn. Another figure holds a penis longer than he is tall, pointing it at the sole large woman in the scene. She stands in front of a platform on which a faceless body lies prone, wearing what looks like the striped animals’ fur. The body resembles the females copulating in this and the previous scene. It is the only figure shown with its arms lowered, probably indicating death in a ritual sacrifice. A small dog is also at the center.

“The last full scene contains no obvious women at all, though the floating bodies on the upper right may be female. Ithyphallic males and a bisexual take part in a frenzied dance. One male seems to have his arm around another while a loner near the bottom seems to be masturbating as a parade of tiny infants streams from his erection. It looks a lot like a frat party. There are four additional scenes that seem more like sketches. Two include a pair of dogs and another depicts male and female torsos with multiple heads. The last figure has a very long penis but the body of a woman and seems to be wearing a conical hat. I think of it as the artist, though no artist could have carved such a large, complex, and detailed tableau in a single prehistoric lifetime.

World's Oldest Pornography in Xinjiang: a Link to the West?

Mary Mycio wrote in Slate.com, “While fascinating in themselves, the petroglyphs also reveal a great deal about the earliest human settlement in China’s westernmost region. The intricately carved faces all display the long noses, thin mouths, and defined eye ridges of the Caucasian face. The people in the petroglyphs came from the West. While unprecedented in Central Asia, the iconography echoes images far to the west. Triangular female figures with the arms held like those in the petroglyphs often appear on Copper Age pottery from the Tripolye culture in what is now Ukraine. The dog symbols are also strikingly similar. [Source: Mary Mycio, Slate.com, February 14, 2013]

“Could the cultures be related despite a distance of 1,600 miles and an untold number of years? The answer depends on who created the petroglyphs. While Chinese scholars attribute them to nomadic cultures from 1000 B.C., Davis-Kimball points out that nomads generally create portable art and not huge tableaus. The makers of the petroglyphs had to have been a sedentary people, since the elaborate artworks appear to have been carved over a period of centuries. This narrows the potential candidates down considerably. The only time in prehistory when sedentary people are known to have populated the region was during the Bronze Age, the millennium prior to 1000 B.C.

2nd century A.D.cup

found in Xinjiang with

Greco-Roman gladiator

“The oldest and most intriguing bodies from this period came from a 20-foot-high, man-made sand mound about 300 miles south of the petroglyphs. Known as Xiaohe, or Small River Cemetery No. 5 (SRC5), it was found in 1934 but then forgotten. The site is in a remote, restricted desert where China conducted nuclear tests. Rediscovered in 2000, the site had to be completely excavated in the following years to protect it from looters. Under the sand lay five layers of burials, from which 30 well-preserved desiccated corpses were recovered, the oldest dating to 2000 B.C.

“Viktor Mair, a professor of Chinese language and literature at the University of Pennsylvania and one of the foremost experts on the mummies, writes that SRC5 was “a forest of phalluses and vulvas … blanketed in sexual symbolism.” The torpedoes were phallic symbols marking all the female graves, while the “oars” marking the male burials represented vulvas. Many female burials contained carved phalluses at their sides, and the mound also contained large wooden sculptures with hyperbolized genitalia. “Such overt, pervasive attention to sexual reproduction is extremely rare in the world for a burial ground,” according to Mair.

“DNA from the male corpses shows Western origins, while females trace to both East and West. Mair and other scholars think that the mummy people’s ancestors were horse riders from the Eastern European steppe who migrated to the Altai in Asia around 3500 B.C. After 1,500 years, some of the Altai people’s descendants, herding cattle, horses, camels, sheep, and goats, ventured south into what is now the Xinjiang region. Squeezed between the Tien Shan Mountains and the hot Taklimakan Desert, it is one of the world’s most hostile environments—a place so harsh that the Silk Road would later detour north or south to avoid it. But satellite photographs show ancient waterways in what is now barren desert, allowing those pioneers to survive in green oases in 2000 B.C.

“It must have been a precarious existence, with staggeringly high infant and juvenile mortality. Perhaps that explains the exaggerated attention to sex and procreation at the cemetery and the high status of certain women. The largest phallic post at SRC5 was painted entirely red and stood at the head of an old woman buried under a bright red coffin. Four other women were buried in rich graves that stood apart from the others.

“The fact that the world’s most sexually explicit graveyard was located a few hundred miles from the most sexually explicit petroglyphs can’t have been a coincidence. When I asked Mair if the petroglyphs could have been created by the people who buried their dead in SRC5, he said it was plausible. Perhaps the new immigrants carved the scenes to record their most important rituals for posterity.

“Mair also noted that Caucasian features and a cultural obsession with sex aren’t all that linked the two sites, both of which are in the areas of Bronze Age settlements. Almost every one of the SRC5 mummies—as well as Bronze Age mummies from other locations—was buried with a flamboyant conical hat, made of felt and decorated with feathers. Though stylized in the petroglyphs, the headdresses on the female figures are also conical with wispy decorations that could be feathers.

“The implications are tantalizing. Could the earliest scenes in the tableau represent fertility rituals originally brought from Europe by the migrants’ ancestors in 3500 B.C.? Do the large females represent high-status women like those buried in SRC5’s richest graves? Does the smaller size of the copulating females signify lower rank? If the two sites are indeed linked, why are men bare-headed in the petroglyphs but all wearing hats in the graves? Could they have been the bisexual shamans in the tableau? Or, as one Chinese scholar has suggested, were penises added to some of the female figures later, possibly signifying the shift from matriarchy to patriarchy? And is the iconography really linked to the Tripolye culture in the West or is it just parallel cultural evolution? These are just some of the mysteries surrounding the Kangjiashimenji Petroglyphs. Hopefully, now that the political pressures have abated, the site will receive deeper study. But whatever the answers, if any are ever found, the tableau is at the very least a spectacular demonstration of sex as one of the driving forces behind the creation of art.

Early Horsemen

Archaeologists working in Outer Mongolia and Inner Mongolia in China have uncovered the remains of more than 100 walled towns and cities of settled people dating back as far as the 3rd millennium B.C. and found extraordinarily beautiful artifacts such as stone altars and jade dragons. Scattered around Outer Mongolia are burial stones organized in squares and circles. Some cover slab-lined tombs and are thought to date as far back as to 2000 B.C.

Around 1500 B.C., Mongolia became colder and drier — a climate more conducive to grasslands than crops — prompting a shift from a crop-based to livestock-centered society. Cattle was raised in areas where pastures were rich. Sheep were raised in areas where the pastures were sparser.

In 1995, perfectly preserved mummified remains of a Scythian nomad and his horse were unearthed from the Ukok Plateau in Siberia near where China, Mongolia and Russia all met. The 3,000-year horseman wore braids, embroidered trousers, a fur coat, high boots. A large elk was tattooed across his back and chest.

The Scythians were Indo-Iranian horse people who migrated from Central Asia near China to the European Steppe north of the Black Sea around 700 B.C. For 400 years they dominated an area that stretched from the Danube across the Ukraine, Crimea and southern Russia to the Don River and the Ural Mountains and then mysteriously vanished. The Scythians preceded the Huns, Turks and Mongols by many centuries. The were not a unified group but rather a confederation of related, warring nomadic tribes. It is believed that they spoke an Indo-European language similar to Persian.

Uighurs arrived in the 10th century. See Uighurs

Xinjiang and the Silk Road

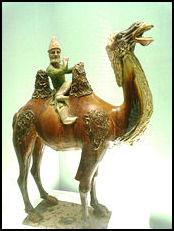

Many Silk Road caravans traveled through Xinjiang. Traders traveling between the Middle East, Europe and western China traveled through the passes between Xinjiang and Central Asia. Traders traveled between India and western China traveled on Himalayan caravan routes over Karakoram Pass between Kashgar in Xinjiang and the Gilgit and Hunza valleys in present Pakistan.

Xinjiang had many important trading posts along the Silk Road and remained a center for the confluence of various cultures over many centuries. The Kharosthi script, for example, was used before the 3rd century; while Kuchean, a branch of the Tocharian language, was used before the 9th century. Source: Guo Shuhan, China Daily August, 18 2010]

Describing Kashgar Marco Polo wrote: "The people are for the most part idolaters, but there are also some Nestorian Christians and Saracens...the inhabitants live by trade and industry. They have fine orchards and vineyards and flourishing estates. Cotton grows here in plenty, besides flax and hemp. The soil is fertile and productive of all the means of life. The country is the starting point from which many merchants set out to market their wares all over the world."

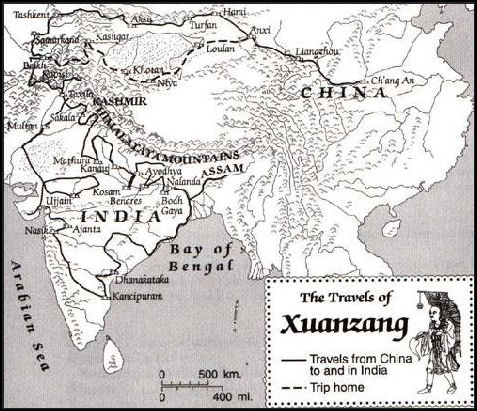

Silk Road Route in Western China

The overland Silk Road route to the west began in Changan (Xian), the capital of China during the Han, Qin and Tang dynasties (206 B.C. to A.D. 906). It stopped in the towns of Zhangye, Jiayuguan, Langzhou, Yumen, Anxi and Nanhu before dividing in three main routes at Dunhuang.

The three main routes between Dunhuang and Central Asia were: 1) the northern route, which went through northwest China through the towns of Hami and Turpan to Central Asia: 2) the central route, which veered southwest from Turpan and passed through Kucha, Aksu and Kashgar; and 3) the southern route, which passed through the heart of the Taklamakan Desert via the oasis towns of Miran, Khotan and Yarkand before joining with the central route in Kashgar.

On the southern route through western China the going began getting difficult near present-day Lanzhou, where the "Gate of Demons," marked the approach to an area, which the writer Mildred Cable said featured "rushing rivers, cutting their way through sand...an unfathomable lake hidden among the dunes...sand-hills with a voice like thunder" and "water which could be clearly seen and yet was a deception."

The going started to get really rough around the Yumenguan (Jade Gate Pass, near Dunhuang), traditionally regarded as the frontier of Chinese Turkestan and entrance to the vast and inhospitable Taklamakan Desert. where Cable wrote, the desert "is a howling wilderness, and the first thing which strikes the wayfarer is the dismalness of its uniform, black, pebble strewn surface." From here the Silk Road followed a line of oases to Kashgar or veered north into present-day Kazakhstan.

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “The routes around the Takla Makan desert in the Tarim Basin connected the Chinese capitals at Ch'ang-an (modern Xi'an) and Loyang with the western frontiers from the Han to Tang periods. The routes divided into northern, southern and central branches around the Tarim Basin at Dunhuang. The northern route started from the Jade Gate outside of Dunhuang and proceeded to the oasis of Turfan, near the Buddhist cave complex at Bezeklik. From Turfan, this route followed the southern foothills of the Tien-shan mountains to Karashahr and Shorchuk (near modern Korla) before reaching Kucha, an oasis surrounded by Buddhist cave complexes such as Kyzil and Kumtura. The northern route continued through Aksu, a junction for routes over the Tien-shan, and Maralbashi, near the Buddhist caves of Tumshuk, to Kashgar, where the southern route reconnects. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, Simpson Center for the Humanities, depts.washington.edu/silkroad *]

“The southern route began at the Yang-kuan gate outside of Dunhuang and continued to oases on the southern rim of the Takla Makan desert such as Miran, Charklik, Cherchen, Endere, and Niya. This route followed the northern base of the Kun-lun mountains to Khotan and Kashgar. An intermediate route from Dunhuang led to the military garrison at Lou-lan on Lop-nor Lake, where branches diverged to Miran on the southern route and Karashahr on the northern route. Travelers' itineraries around the Tarim Basin depended on their goals and destinations, the political and physical environment, and economic conditions. *\

Archeological Evidence of the Silk Road Trade in China

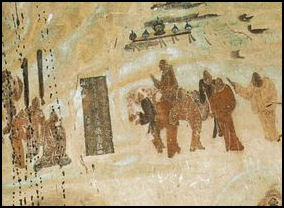

Zhang Qian in a 7th century

Dunhuanshang mural

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Many artifacts demonstrate long-distance trade connections and cultural transmission between China, Khotan (Hotan in present-day Xinjiang, China) on the southern silk route, and the northwestern frontiers of the Indian subcontinent. Fragments of finely woven tabby silk from China reflect long-distance trade or tribute relations with Khotan during the third or early fourth centuries CE. Coins of Indo-Scythian (Saka) and Kushan rulers (see essays on Sakas and Kushans) and an incomplete manuscript of a Gandhari version of the Dharmapada were found near Khotan. Other items imported to Khotan from the northwestern Indian subcontinent included small Gandharan stone sculptures and moulded terracotta figures. Long-distance trade in highly valued Buddhist items (such as manuscripts, small sculptures, miniature stupas, and possibly relics) prefigured later connections between Buddhist communities in Khotan and Gilgit. Khotan was not only a regional commercial and religious center of the southwestern Tarim Basin, but also functioned as a connecting point between China, India, western Central Asia, and Iran. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, Simpson Center for the Humanities, depts.washington.edu/silkroad *]

“The Shan-shan kingdom, which flourished on the southern silk route between Niya and Lou-lan until the fourth century CE, benefited from long-distance trade between China and eastern Central Asia. In exchange for luxury items from these regions, Chinese silk was probably used in commercial transactions, since silk was preferred to copper coins as currency. The economic prosperity of agricultural oases and trading centers on the southern silk route enabled Buddhist communities to establish stupas and monasteries. As Marilyn Rhie observes in Early Buddhist Art of China & Central Asia (vol. 1, p. 429), Buddhist sculptures from Miran and Khotan display many similarities with the artistic traditions of Gandhara, Swat, and Kashmir in the northwestern Indian subcontinent. Mural paintings at Miran reflect ties with both the art of western Central Asia and northwest India (Rhie, p. 385). Administrative documents found at Niya, Endere, and Lou-lan written in the Gandhari language and Kharosthi script demonstrate linguistic and cultural ties between the southern silk route oases and the northwestern Indian subcontinent in the third to fourth centuries CE. *\

“Intermediate routes through Karashahr and northern routes through Turfan probably eclipsed the southern route by the fifth century CE (according to Rhie, p. 392). Many of the most important archaeological sites on the northern silk route are clustered around Kucha and the Turfan oasis. Mural paintings in cave monasteries, stupa architecture, artifacts, and other remains from approximately the third to seventh centuries at sites around Kucha show closer stylistic affinities with the northwestern Indian subcontinent, western Central Asia and Iran than with China. Sites located further east along the northern silk route belonging to relatively later dates in the seventh to tenth centuries typically reveal more Chinese and Turkish elements. Mural paintings from the cave monastery of Kyzil demonstrate continuities between the art of the western part of the northern silk routes and the artistic traditions of Swat, Gandhara and Sassanian Iran in the middle of the first millennium CE. Monks and merchants traveling on the northern and southern silk routes were responsible for maintaining commercial, religious, and cultural contacts between India, Central Asia, and China. *\

“Material remains from sites along the silk routes reflect close relations between long-distance trade and patterns of cultural and religious transmission. Demand for Chinese silk and luxury commodities which were high in value but low in volume stimulated commerce. Valuable items such as lapis lazuli, rubies, and other precious stones from the mountains of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Kashmir probably led travelers to venture into these difficult regions. Some of these products became popular items for Buddhist donations, as attested in Buddhist literary references to the "seven jewels" (saptaratna) and reliquary deposits (see Xinru Liu, Acient India and Ancient China, pp. 92-102). Long-distance trade in luxury commodities, which were linked with the transmission of Buddhism [see essay on Buddhism and Trade], led to increased cultural interaction between South Asia, Central Asia, and China. *\

Early Silk Road Explorers

More than 1,300 years before Marco Polo left Italy for China on the Silk Road, Chinese explorers were traveling nearly as far to reach Central Asia and the Middle East. In 138 B.C., the Chinese explorer Chang Chien (Zang Qian) was sent westward by Emperor Wu (140-87 B.C.) with the assignment of finding allies to fight the Xiongnu. He was captured by the Xiongnu soon after departing and was held in captivity for 10 years before he escaped and crossed the Pamir mountains to reach the Fergana Valley

Chang Chien reached Syria, and possibly Egypt, and returned to China 19 years after he set out and long after the Xiongnu were subdued. In the first great account of Silk Road travel he described the pleasures of Central Asian wine and fantastic animals such as the "heavenly horses" of the Fergana Valley that had striped bodies and sweated blood.

The Chinese monk Fa-hsien left China around A.D. 399 to study Buddhism and locate sutras and relics in India. He traveled from Xian to the west overland on the southern Silk Road into Central Asia and described monasteries, monks and pagodas. He crossed over Himalayan passes into India and ventured as far south as Sri Lanka before sailing back to China on a route that took him through present-day Indonesia. His entire journey took 15 years.

Xuanzang

In A.D. 645, the Chinese monk Xuanzang (Hsuan-tsang) left China for India to obtain Buddhist texts from which the Chinese could learn more about Buddhism. He made it to Central Asia and India despite being held up by surly Chinese guards and guides who abandoned him in the middle of nowhere. In Central Asia he traveled to Turfan, Kucha, the Bedel pass, Lake Issyk-kul, the Chu Valley (near present-day Bishkek), Tashkent, Samarkand, Balk, Kashgar and Khoton before crossing the Himalayas into India.

Xuanzang spent 16 years in India collecting texts and returned with 700 Buddhist texts. His journey inspired the Chinese literary classic "Journey to the West" by Wu Ch'eng-en, a story about a wanderings Buddhist monk accompanied by a pig, an immortal that poses as a monkey and a feminine spirit.

Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “The human skeletons were piled up like signposts in the sand. For Xuanzang, a Buddhist monk traveling the Silk Road in A.D. 629, the bleached-out bones were reminders of the dangers that stalked the world's most vital thoroughfare for commerce, conquest, and ideas. Swirling sandstorms in the desert beyond the western edge of the Chinese Empire had left the monk disoriented and on the verge of collapse. Rising heat played tricks on his eyes, torturing him with visions of menacing armies on distant dunes. More terrifying still were the sword-wielding bandits who preyed on caravans and their cargo’silk, tea, and ceramics heading west to the courts of Persia and the Mediterranean, and gold, gems, and horses moving east to the Tang dynasty capital of Changan, among the largest cities in the world. [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, June 2010]

What kept Xuanzang going, he wrote in his famous account of the journey, was another precious item carried along the Silk Road: Buddhism itself. Other religions surged along this same route — Manichaeism, Christianity, Zoroastrianism, and later, Islam — but none influenced China so deeply as Buddhism, whose migration from India began sometime in the first three centuries A.D. The Buddhist texts Xuanzang carted back from India and spent the next two decades studying and translating would serve as the foundation of Chinese Buddhism and fuel the religion's expansion.

Near the end of his 16-year journey, the monk stopped in Dunhuang, a thriving Silk Road oasis where crosscurrents of people and cultures were giving rise to one of the great marvels of the Buddhist world, the Mogao caves.

Xuanzang's Account of Western China

In A.D. 629, early in the Tang Dynasty period, the Chinese monk Xuanzang (Hsuan Tsang) left the Chinese dynasty capital for India to obtain Buddhist texts from which the Chinese could learn more about Buddhism. He traveled west — on foot, on horseback and by camel and elephant — to Central Asia and then south and east to India and returned in A.D. 645 with 700 Buddhist texts from which Chinese deepened their understanding of Buddhism. Xuanzang is remembered as a great scholar for his translations from Sanskrit to Chinese but also for his descriptions of the places he visited — the great Silk Road cities of Kashgar and Samarkand and the great stone Buddhas in Bamiyan, Afghanistan. His trip inspired the Chinese literary classic “Journey to the West” by Wu Ch'eng-en, a 16th century story about a wandering Buddhist monk accompanied by a pig, an immortal that poses as a monkey and a feminine spirit. It is widely regarded as one of the great novels of Chinese literature. [Book: "Ultimate Journey, Retracing the Path of an Ancient Buddhist Monk Who Crossed Asia in Search of Enlightenment" by Richard Bernstein (Alfred A. Knopf); See Separate Article on Xuanzang]

In A.D. 629 (or 627, depending on the source), Xuanzang set off on a journey to India. It would be 17 years before he would return. Sally Hovey Wriggins wrote: “According to tradition, before Xuanzang left the capital of the great Tang dynasty, Chang’an (Xian), he had a vision of the holy Mount Sumeru. He beheld an unending horizon, symbol of the countless lands he hoped to see. Because the Tang Emperor had forbidden travel in the dangerous western regions, Xuanzang went forth as a fugitive, hiding by day and traveling by night. When the pilgrim finally reached the Jade Gate, he set out with his horse and a guide to cross the Gashun Gobi desert, a distance of 200 miles. [Source: “Xuanzang on the Silk Road” by Sally Hovey Wriggins, author of books on Xuanzang, mongolianculture.com \~/]

The further west he traveled from his starting point of Ch’ang An (Xian) the more difficult his journey became as he had to contend with long stretch of desert, mountain ranges and other obstacles. Of the Taklamaken desert he reported: "As I approached China's extreme outpost at the edge of the Desert of Lop, I was caught by the Chinese army. Not having a travel permit, they wanted to send me to Tun-huang to stay at the monastery there. However, I answered 'If you insist on detaining me I will allow you to take my life, but I will not take a single step backwards in the direction of China'." The officer himself a Buddhist, let him pass. In order to avoid the next outpost, he left the main foot-track and made a detour, which brought him to a place 'so wild that no vestige of life coult be found there. There is neither bird, nor four-legged beasts, neither water nor pasture'."Source: Irma Marx, Silk Road Foundation silk-road.com]

Here, according to Wriggins, “his guide tried to murder him, he lost his way and he dropped his water bag so all the water drained out into the sand. Whether by miracle or by the horse's instinct for finding water, Xuanzang reached the oasis of Hami, known as Iwu in Tang times, the easternmost of a string of oases at the foot of the Tian Shan mountains. From the summits of these mountains, rivers flow down to the desert dunes until they disappear in the sand. The precious water is transported through underground channels called kariz. With fertile land, and the increasingly prosperous trade of China with the West and the West with China, these oases flourished greatly." \~/

On the first leg of his journey Xuanzang reported: ““Leaving the old country of Kau-chane, from this neighbourhood there begins what is called the 'O-ki-ni country (Anciently called Wu-ki). The kingdom of 'O-ki-ni (Akni or Aani) is about 500 li from east to west, and about 400 li from north to south. [p.18] The chief town of the realm is in circuit 6 or 7 li. On all sides it is girt with hills. The roads are precipitous and easy of defence. Numerous streams unite, and are led in channels to irrigate the fields. The soil is suitable for red millet, winter wheat, scented dates, grapes, pears, and plums, and other fruits. The air is soft and agreeable; the manners of the people are sincere and upright. The written character is, with few differences, like that of India. The clothing (of the people) is of cotton or wool. They go with shorn locks and without head-dress. In commerce they use gold coins, silver coins, and little copper coins. [Source: “Xuanzang's Record of the Western Regions”, 646, translated by Samuel Beal (1884), Silk Road Seattle, depts.washington.edu/silkroad |:|]

The king is a native of the country; he is brave, but little attentive to (military) plans, yet he loves to speak of his own conquests. This country has no annals. The laws are not settled. There are some ten or more Sanghârâmas with two thousand priests or so, belonging to the Little Vehicle, of the school of the Sarvâstivâdas (Shwo-yih-tsai-yu- po). The doctrine of the Sutras and the requirements of the Vinaya are in agreement with those of India, and the books from which they study are the same. The professors of religion read their books and observe the rules and regulations with purity and strictness. They only eat the three pure aliments, and observe the method known as the"gradual" one. |:|

See Separate Article XUANZANG: THE GREAT CHINESE EXPLORER-MONK factsanddetails.com ; XUANZANG IN WESTERN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; XUANZANG IN CENTRAL ASIA factsanddetails.com ; XUANZANG IN AFGHANISTAN factsanddetails.com ; XUANZANG IN INDIA (630-645) factsanddetails.com

Marco Polo in Western China

After passing through the Pamirs, Marco Polo entered western China near Tazkoragan, near where China, Afghanistan and Tajikistan meet, and traveled to Kashgar. At this point in their journey the Polos had been traveling for about two years and had covered around 5,000 miles and still had 2,600 miles to go before they reached their goal:Shangdu (Xanadu), not so far from Beijing. The Polos followed the Silk Road caravan route through China. They stopped in Kashgar and then crossed the Taklamakan Desert to the north-central Chinese towns of Dunhaung, Nanhu, Anxi, Yumen, Jiayuguan and Zhangye and finally Shangdu. The Polos traversed the forbidding gravel plains and sand dunes of the Taklamakan Desert, whose names means "go in and you won't come out." They most likely were part of a caravan of double-humped Bactrian camels that traveled about 15 miles a day with a month's supply of food, stopping at infrequent water holes and oases. Marco wrote, of oases that "have great abundance of all things and places where "nothing to eat is found" and "you must always go a day and night before you find water."

Marco Polo wrote: "It often seems to you that you hear many instruments sounding and especially drums. The old people believe they are hearing devils speak...One night I heard, three times, a terrible noise, like crying, like someone dying." "Beasts and birds there are none," he wrote, "because they find nothing to eat. But I assure you that one thing is found here, and that a very strange one...When a man is riding by night through this desert and something happens to make him loiter and lose touch with his companions...the spirits begin talking in such a way that they seem to be his companions. Sometimes, indeed, they even hail him by name. Often these voices make him stray from the path, so that he never finds it again. And in this way many travelers have been lost and have perished."

China and Xinjiang

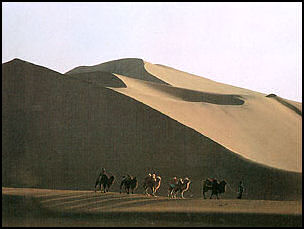

Sand dunes in Xinjiang

China maintains that Xinjiang has been an integral part of China since 60 B.C. and that it is has maintained control of the region with the exception of a few brief periods. Muslims in Xinjiang refute this claim. The Chinese say they established military garrisons in what is now Xinjiang as early as 200 B.C. and say the region came under Chinese control briefly during the Han dynasty in A.D. 50. China returned to again during the Tang dynasty (618-907) but withdrew after the dynasty collapsed. Xinjiang was part of the Mongol-Yuan empire which also encompassed China. The oldest evidence of Chinese presence are some graves at a place called Astana, believed to have been a military garrison that existed there sometime between the A.D. 3rd and the 10th century

The Chinese periodically sent in the military to claim Xinjiang, with the soldiers followed by farmers and workers building irrigation works. In "Xinjiang: China’s Muslim Borderland" James A. Millward and Peter C. Perdue wrote: “By first establishing military and civil administrations and then promoting immigration and agricultural settlements, it went far towards assuring the continued presence of China-based power in the region.”

Xinjiang was largely independent of China during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), a fact that China does not acknowledge in its modern history books, and remained that way until 1759. During the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), China returned to Xinjiang because of its strategic location and resources.

In the 18th century the Emperor Qianlong launched a campaign to claim Xinjiang after effort to rule it through Mongolian and Uighur proxies failed. His campaign went far beyond anything that occurred before. More than 50,000 troops were demobilized and offered benefits if they stayed and farmed. Free land and seeds were given to Chinese who migrated there.

Conquests by China in the 18th century in western and southern China nearly doubled the country's size. The Chinese did not exert much control over Xinjiang until the 19th century. Even then Chinese hold on the region was tenuous. Frequent rebellions prevented the Chinese from solidifying their control of the region until mid 20th century. Xinjiang wasn't incorporated into China until 1955, six years after the People's Republic was created.

Chinese Take on Early Xinjiang History

According to the Chinese government: “Xinjiang has been part of China since ancient times. The Uyghurs, together with other ethnic groups, have opened up the region and have had very close economic and cultural ties with people in other parts of the country, particularly central China. Xinjiang was called simply "Western Region" in ancient times. The Jiaohe ruins, Gaochang ruins, Yangqi Mansion of "A Thousand Houses," Baicheng (Bay) Kizil Thousand Buddha Grottoes, Bozklik Grottoes in Turpan, Kumtula Grottoes in Kuqa and Astana Tombs in Turpan all contain a great wealth of relics from the Western and Eastern Han dynasties (206 B.C. - A.D.220). They bear witness to the efforts of the Uyghurs and other ethnic groups in Xinjiang in developing China and its culture. [Source: China.org china.org |]

“Zhang Qian, who lived in the second century B.C., went to the Western Region as an official envoy in 138 and 119 B.C., further strengthening ties between China and central Asia via the "Silk Road." In 60 B.C., Emperor Xuan Di of the Western Han Dynasty established the Office of Governor of the Western Region to supervise the "36 states" north and south of the Tianshan Mountains with the westernmost border running through areas east and south of Lake Balkhash and the Pamirs. |

“During the Wei, Jin, Northern and Southern dynasties (220-581 A.D.) the Western Reigon was a political dependent of the government in central China. The Wei, Western Jin, Earlier Liang (317-376), Earlier Qin (352-394) and Later Liang (386-403) dynasties all stationed troops and set up administrative bodies there. In 327, Zhang Jun of the Earlier Liang Dynasty set up in Turpan the Gao Chang Prefecture, the first of its kind in the region. |

Xinjiang During the Imperial Chinese Period

According to the Chinese government: “In the mid-seventh century, the Tang Dynasty established the Anxi Governor's Office in Xizhou (present-day Turpan, it later moved to Guizi, present-day Kuqa) to rule areas south and north of the Tianshan Mountains. The superintendent's offices in the Pamirs were all under the jurisdiction of the Anxi Governor's Office. In the meantime, four Anxi towns of important military significance — Guizi, Yutian (present-day Hotan), Shule (present-day Kaxgar) and Suiye (on the southern bank of the Chu River) — were established. In the early eighth century, the Tang Dynasty added Beiting Governor's Office in Tingzhou (present-day Jimsar). The Beiting and Anxi offices, with an administrative and military system under them, implemented effectively the Tang government's orders. [Source: China.org china.org |]

“In the early 13th century, Genghis Khan (1162-1227) appointed a senior official in the region. The Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) established Bieshibali (present-day areas north of Jimsar) and Alimali (present-day Korgas) provinces. The Hami Military Command was set up during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). During the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) the northern part of the Western Region, namely, north of Irtish River and Zaysan Lake, was under Zuo Fu General's Office in Wuliyasu. The General's Office in Ili exercised power over areas north and south of the Tianshan Mountains, east and south of Lake Balkhash and the Pamirs. Xinjiang was made a province in 1884, the 10th year of the reign of Emperor Guang Xu. |

“In the early 13th century, Genghis Khan (1162-1227) appointed a senior official in the region. The Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) established Bieshibali (present-day areas north of Jimsar) and Alimali (present-day Korgas) provinces. The Hami Military Command was set up during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). During the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) the northern part of the Western Region, namely, north of Irtish River and Zaysan Lake, was under Zuo Fu General's Office in Wuliyasu. The General's Office in Ili exercised power over areas north and south of the Tianshan Mountains, east and south of Lake Balkhash and the Pamirs. Xinjiang was made a province in 1884, the 10th year of the reign of Emperor Guang Xu. |

“The Qing government introduced a system of local military command offices in Xinjiang. It appointed the General in Ili as the highest Western Regional Governor of administrative and military affairs over northern and southern Xinjiang and the parts of Central Asia under Qing influence and the Kazak and Blut (Kirgiz) tribes. For local government, a system of prefectures and counties was introduced. |

“The imperial court began to appoint and remove local officials rather than allowing them to pass on their titles to their children. This weakened to some degree the local feudal system. The court also encouraged the opening up of waste land by garrison troops and local peasants, the promotion of commerce and the reduction of taxation, which were important steps in the social development of Uyghur areas. |

“Xinjiang was completely under Qing Dynasty rule after the mid-18th century. Although political reforms had limited the political and economic privileges of the feudal Bokes (lords), and taxation was slightly lower, the common ethnic people's living standards did not change significantly for the better. The Qing officials, through local Bokes, exacted taxes even on "garden trees." The Bokes expanded ownership on land and serfs, controlled water resources and manipulated food grain prices for profit.” |

Iparhan (Xiangfei): Loving Consort or Sex Slave?

The supposed tomb of “Princess Fragrant”—a consort of the Qing Emperor Qianlong— is a major tourist attractions for Chinese in Kashgar, even though historians doubt she is buried there. The princess is known to Uyghurs as Iparhan and to Chinese as Xiangfei, or Fragrant Concubine, which can further be euphemized into Princess Fragrant. Reporting from Kashgar,Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times, “Busloads of Chinese tourists who converge on the Afaq Khoja Mausoleum each day are mostly interested in a single raised crypt amid the dozens of tombs ensconced under the shrine’s soaring 17th-century dome. It is the one said to belong to Iparhan, a Uyghur imperial consort, who, according to legend, was so sweetly fragrant that she caught the attention of a Chinese emperor 2,700 miles away in Beijing — and was either invited to live with him or dragooned into the palace as a trophy of war. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, August 18, 2014 ~~]

“The love between her and the Qianlong emperor was so strong, after she died, he sent 120 men to escort her body back here for burial,” one guide explained, eliciting nods and knowing smiles from the crowd. “It was a journey that took three years.” But with the group out of earshot, a local resident offered up a starkly different version, describing Iparhan as a tragic figure, little more than a sex slave who was murdered by the emperor’s mother after she repeatedly rejected Qianlong’s advances. “The story that most Chinese know is completely made up,” said the man, an ethnic Uyghur, who asked that his name be withheld for fear of angering the authorities. “The truth is she isn’t even buried here.” ~~

“Although the story of Iparhan was first popularized in the early 20th century, party-backed historians have made significant alterations. Most seek to turn her into a vehicle for conveying enduring amity between Han and Uyghurs, whose Central Asian culture, Muslim faith and Turkic language set them apart from the Han. Earlier versions of the story cast Xiangfei as a defiant beauty, captured by the Qing during battle, who kept daggers in her sleeve and remained chaste to the end, when she was either killed by palace eunuchs or forced to commit suicide. But that narrative has been supplanted by a happy-ending tale of romance that celebrates the emperor’s efforts to win her affections by building a miniature Kashgari village outside her window in Beijing and showering her with the sweet melons and oleaster of her homeland. ~~

“These days, Xiangfei is the subject of poems, plays and television shows as well as the namesake of a chain of roast-chicken restaurants, a brand of sun-dried raisins, and, not surprisingly, a line of perfumes. Rian Thum, a professor of Uyghur history at Loyola University New Orleans, said that in addition to suggesting longstanding affections between Han and Uyghur, the mythicized Xiangfei served to reinforce the image of Uyghur women as exotic, strong-willed and slightly dangerous. “The fact that Uyghurs are sexualized and exoticized by so many Han Chinese makes the Xiangfei story very appealing,” he said. ~~

Uyghur Views on the Iparhan (Xiangfei) Myth

Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times, “In Xinjiang, as Uyghur resentment over Chinese rule boils over Into increasing bloodshed, this propagandistic approach to history has taken on greater urgency. Over the past year, at least 200 people have been killed here, some of them Han murdered by what the government calls “terrorists,” but many of them Uyghurs shot by security forces under murky circumstances. At times like these, it would seem that Iparhan is just the salve that China needs. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, August 18, 2014 ~~]

“Many Uyghurs also find the popularized story of Xiangfei galling, although their ire is often focused on the Afaq Khoja Mausoleum — a hallowed Sufi shrine and burial place for a clan that once ruled the Kashgar region — and its transformation into a prop for a Chinese fable. Archaeologists, they note, long ago identified the grave of a concubine named Xiangfei outside Beijing. ~~

“Some of the resentment also stems from the government’s decision to turn what was an important site for pilgrimages into a tourist attraction devoid of religious meaning. These days the site is managed by a Chinese company that charges an entry fee. Professor Thum said the government had largely succeeded in shaping both Han and Uyghur understandings of the shrine, especially its association with the rebellious Khojas, who fought off the Qing occupiers and established a short-lived independent state in the mid-19th century. “To their credit,” he said, “the government took a symbol of Uyghur resistance to Chinese rule and turned it into a vehicle for a message they want to get out.” ~~

Image Sources: Uighur images website; Silk Road Foundation; Wikipedia; Shanghai Museum; British Museum

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2015