EWENKI SOCIETY

from an Ewenki wedding

Ewenki clans have traditionally acted independently of one another since the last tribal Ewenki chief died in 1761. Each clan is headed by a chief, who presides over meetings and settles disputes and otherwise acts like any other member of the clan. Blood feuds have often occurred between clans, which often recruited new members to increase their strength. Social control has traditionally been effected through persuasion and public opinion; to lose face was a grave matter. [Source: Liu Xingwu, "Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China", edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company, 1994) |~|]

Possessions have traditionally been shared with the understanding that anybody could take what they wanted when they needed it and would pay it back when they were able. Hunters have traditionally stored their food, clothes, and tools in their storehouse in the forest, which is never locked. Any hunter is allowed to take food from the storehouse as needed without prior agreement with the owner. When he meets the owner, he should, however, return the amount of food taken.

Poverty and isolation are serious problems faced by the Ewenki. Their scattered communities, harsh environment, and the absence of a market economy has made such problems hard to solve. In some cases Ewenki have been resettled (See Below). Some are okay with that but old timers haven’t liked the disruptions to their traditional way of life. In the past most of the Ewenki were illiterate. Now most learn to read or write at schools set up where they live.

See Separate Article EWENKI AND THEIR HISTORY AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com ; EVENKI AND EVEN factsanddetails.com ; REINDEER factsanddetails.com REINDEER AND PEOPLE factsanddetails.com; ETHNIC GROUPS IN NORTHERN CHINA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Ecological Migrants: The Relocation of China's Ewenki Reindeer Herders” by Yuanyuan Xie Amazon.com; “Reclaiming the Forest: The Ewenki Reindeer Herders of Aoluguya” by Åshild Kolås and Yuanyuan Xie Amazon.com; The Fire God Festival of the Ewenki Ethnic Group (Bilingual Version of English and Chinese) by Yan Xiangjun and Pi Xuan Amazon.com; “The Moose of Ewenki” (Children’s Book) by Gerelchimeg Blackcrane, Jiu Er, Helen Mixter Amazon.com; “The Ewenki Dialects of Buryatia and Their Relationship to Khamnigan Mongol (Tunguso-Sibirica) by Bayarma Khabtagaeva Amazon.com; “Reindeer Herders in My Heart: Stories of Healing Journeys in Mongolia” by Sas Carey (Author) Amazon.com; “The Minorities of Northern China: A Survey” by Henry G. Schwarz (1984) Amazon.com; “On the Edge: Life along the Russia-China Border” by Franck Billé and Caroline Humphrey Amazon.com; “Evenki (Languages of the World) by N. I A Bulatova Amazon.com; “Evenki Economy in the Central Siberian Taiga at the Turn of the 20th Century: Principles of Land Use” by Mikhail G. Turov, Andrzej W. Weber, et al. Amazon.com; “Katanga Evenkis in the 20th Century and the Ordering of their Life-World” by Anna A. Sirina, David G. Anderson, et al. Amazon.com; “Shamanism in Siberia: Animism and Nature Worship: The Shaman Spirit of Buryat, Altai, Yakut, Tuvan, Evenki, Sakha, Chukchi, Dolgan, Khanty, Mansi, Amazon.com; “The Flying Tiger: Women Shamans and Storytellers of the Amur” by Kira Van Deusen Amazon.com

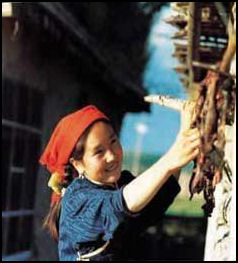

Ewenki Life

Most Ewenki are involved in animal husbandry or agriculture. A few still hunt for a living. Most have regular jobs or herd horses, oxen and goats and grow wheat, sorghum, rye, oats and buckwheat. Some sell reindeer antlers to Koreans and Chinese for use in Asian medicines. Under the Communists, some Ewenki were settled in villages; others were allowed to practice their herding ways. Most dream of practicing some form of traditional reindeer herding and hunting while enjoying modern conveniences such as hot showers, cell phones, decent incomes and televisions.

The migrations and divisions of the Ewenki over time has produced scattered communities. Because of the significant difference of natural environments in which these communities live, their lifestyle are also quite different. Those living in Ewenki Autonomous Banner in Chen Barag practice animal husbandry while those in Nehe in Heilongjiang Province are farmers. Those inhabiting Ergun Zuo Qi are hunters. They still ride reindeer while hunting, and are thus called “Deer back riding Ewenki." Those dwelling in Butha Qi, Arun Qi, and Morin Dawa Qi have a mixed economy, half farming and half hunting; [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

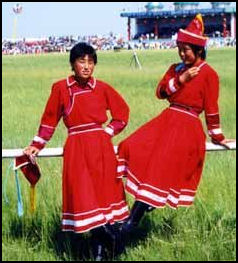

Women in front of birchbark tent In the old day, both sexes wore long fur robes covering the ankles, and a long coat down to the knees. The cuffs and the bottom of the women's robes were embroidered with multicolored figures and designs. They all wore fur hats and had distinctive mittens and gloves. Today, Ewenki mostly wear cloth robes, and padded cotton garments in winter. The dress of urban Ewenki is similar to that of the Chinese. They mostly don traditional clothes during festivals and weddings.

Birch bark plays an important role in the Ewenki' daily life. Most of their utensils for hunting, fishing and milking are made of birch bark. Birch bark are also applied to make dishware, wine-brewing container, vessels, houses, and fences. They even wrap dead bodies with birch bark. What's more, Ewenki people make clothes with birch bark. Caps and shoes made of birch bark are very popular among Ewenki people. Canoes made of birch bark have a unique design and provide an easy way to get around the many lakes and rivers where the Ewenki live. [Source: Chinatravel.com]

The Ewenkis make wide variety of household utensils from birch bark. They also make a large variety of products from animal skins. Ewenki have traditionally enjoyed tobacco and tea and traded animal skins for them. When Ewenki hunters go out on long hunting trips, they leave whatever they cannot take along — foodstuffs, clothing and tools in unlocked stores in the forests. See Society Above.

Ewenki Nomads

Nomadic Ewenki live in nomadic units called nimals, comprised of several nuclear families, and migrated primarily between winter woods and summer pastures for reindeer.. The migration southward for the winter takes place after the reindeer mating season. In the old days, nomadic Ewenki lived in "xianrenzhu", conical teepee-like tents covered by animal hides and birch bark, herded reindeer and hunted for elk, rose deer and squirrels in groups of four or five hunters with shotguns and dogs. Food was shared equally, with the hunter who made the kill customarily taking the least desirable part. Special care was taken to make sure the sick, aged and disabled were provided for. Reindeer provided a means of transport for belongings. Hunters sometimes rode them or were pulled by them on ski boards. [Source: Liu Xingwu, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

The few Ewenki that still practice nomadism live in yurts (circular felt tents) or 10-foot-square canvas tents and keep themselves warm and cook from a fire, whose smoke escapes from hole in the canvas. They sleep on low beds, primarily eat reindeer flesh and organs and spend their day doing chores like cooking, milking the herd, gathering berries, making cream, looking for strays, watching out for wolves, doing embroidery and washing clothes.

Some Ewenki that belong to the Aolu Guya Ewenkii tribe in the Greater Hinggan Mountains in Inner Mongolia still live the nomadic life. One elderly woman named Suo Maliya described by the Los Angeles Times and the China Daily lives with five other nomads and owns a herd of 300 reindeer. The nomads are regarded as the last of their kind. The reindeer are valued at $735 a piece which makes their herd worth $219,000. Some younger Ewenki have shown an interest in reindeer herding but most aren’t interested. [Source: China Daily February 5, 2009]

Ewenki Customs and Hospitality

The Ewenkis are honest, warm-hearted and hospitable people. A visit by a guest is treated as a happy event. A fur cushion is offered by the host and the guest sits on the cushion wherever it placed. Moving to a different place is considered rude. Guests in the pastoral areas are often treated to tobacco, milk tea and stewed meat by the Ewenki hosts. In hunting and reindeer herding areas, the hostess serves reindeer milk and meat, homemade wild fruit wine and toasted cake. Elk-nose meat sausages may be offered as a special treat. The host pours a few drops of wine on the fire, takes a sip for himself, and then hands the cup over to the guest. [Source: China.org][Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

Ewenki hospitable is summed by the Ewenki expression: "“"People coming from afar cannot carry their own house on their back; nor can we when we go out... If you are friendless, you will be treated alike some day. People are willing to lodge in a fire-warmed house, just like birds are willing to perch on a flourish tree." For honored guests, a reindeer is slaughtered with a slit to the throat. The pelt is peeled back, the organs are removed, blood is drained and the meat is cut into four-inch cubes. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China ~]

The Ewenki have traditionally observed their etiquette rules strictly, especially respect towards the elderly. Young people are expected to jump to their feet to respond to an elder's call immediately and cannot start dinner until the elders have started to eat. Ewenki youths have to address their elders with respectful language. In the old days when the young and old encountered each other on horseback, young people were expected to dismount.

The Ewenki are in awe of fire and treat it as if it is divine. They never use anything with blades to stir the fire, or pour water or throw filthy things into the fire. They make a toast to the fire before eating meats, having dinner or drinking. The Ewenki in the pasturing areas hold a ritual for the fire god: a table of offerings is put before the fire, with lights and colorful lists around the fire stand. In the fire stand, there is a frame, on which people place the whole breastbone of a sheep. They pour sheep oil on it, light the fire, and put all kinds of offerings into the fire. Meanwhile, the woman in charge of the ritual kneels before the fire, praying for the forgiveness from the Fire God, in the case that some family members have done something improper to the fire. After that, the whole family kowtows to the fire, and nobody is allowed to stir the fire or rake out the cinders for three days. The fire plays an important role in the Ewenki’s daily life. Besides, they believe that the host of the fire is divine, and the host of the fire is the ancestor of every household. If the host of the fire is lost, the Ewenki believe, the family will decline. That is why the Ewenki are so pious to the fire. See Folklore Blow

Ewenki Families

The Ewenki live in small families arranged along patrilineal (tracing ancestry through the father's bloodline). Out of the need to help each other hunt and search for pastures, they have traditionally formed nomadic villages. Villages, whether nomadic or settled, have a clan structure in which each family has blood ties with the other families. The Ewenki used to adopt members of other clans to increase the population of their clans; they even adopted captives for the same reason. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Socialization is informal and begins early. Hunting and tending herds are central themes. Competitions have traditionally been used to encourage the learning of necessary skills. Both boys and girls participate in horse racing and lassoing horses. They start to look after calves at age six or seven. Boys learn to ride a horse by age seven, and are taught how to break a horse shortly afterward. Girls learn to milk cows at age ten. Children show respect to their elders by bending at the knee and cupping the hands in front of the chest. Seating arrangements and beds are assigned on the basis of age. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

According to the "Encyclopedia of World Cultures": Descent and inheritance traditionally followed the male line. The family head was the eldest male, but pieces of family property, such as shotguns and reindeer, were passed on to the youngest son. Ewenki kinship terminology is partially classificatory and partially descriptive. While terms for father, mother, husband, and wife are definite and clear, other terms are not, making very little distinction between relatives from the father's side and those from the mother's side. Sex distinctions are clear in some instances but not so clear in others. The Ewenki seem to be more conscious of relative age than of generation differences, and sometimes they use the same term for people of different generations. |~|

Ewenki Marriage

Monogamy is generally practiced. In old days exogamy (marrying outside a community, clan, or tribe) was strictly observed. Members of the same clan were not permitted to marry one another, and those going against this unwritten law would be punished. Divorce is rare. Both levirate, in which a man is obliged to marry his brother's widow, excluding the elder brothers of the husband, and sororate (excluding the elder sisters of the wife) were common. Cross-cousin marriage, as the preferential marriage form, is no longer practiced. Intermarriage with the Daur has a long history, with some families and clans intermarried over generations. The linkage is so strong that the Ewenki and the Daur are called two “familial nationalities."

Most marriages are love matches although sometime arranged marriage occur, in some cases, in the old days, between girls of 17 or 18 and boys of 7 or 9. Young people do not squander opportunities to seek partners as such opportunities are limited in pastoral and hunting due to the great distance between villages and of the clan structure of individual villages. + [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; "Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China", edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company, 1994)]

An Ewenki wedding is an occasion for dancing and merry-making. The marriage is formalized when an elderly women rearranges the brides eight pigtails into two. Most newlywed set up their households with the groom’s clan. Afterward, all members of the clan congratulate the couple. A huge banquet follows, with dancing and singing.

Ewenki wedding

Ewenki Elopement

The custom of “elopement marriage" is sometimes observed. Here, a young man and woman pretend to elope, with both families playing along with the parents of the young man's even preparing a new house for the couple beforehand. The couple carry a series of prescribed rituals with each family, honoring ancestors, asking forgiveness, and begging both sets of parents to accept their marriage. Under the terms of Ewenki elopement in Chen Barag, a couple sets up a felt tent with a xianrenzhu (a traditional teepee-like structure), beside it. In the middle o the night the girls sneaks out off her tent and rides off with her lover. The couple sleeps together in the xianrenzhu.

Explaining how it works, C. Le Blanc wrote: The date of elopement is agreed upon by the young man and woman who are passionately in love. The parents of the male side prepare a new house beforehand and an old woman is waiting there for the eloping girl. After dark, the girl escapes from her family. Riding on horseback, she comes directly to the new house. The old woman unties the girl's eight braids and combs her hair into two large ones. This is a symbol that the marriage is now “legal."[Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

Before dawn, the couple goes to the man's paternal house and kowtows to the fire and to the tablet of his ancestors. Then, two persons are sent to the bride's family, first to offer hada (a ceremonial silk scarf) to her ancestors and then to kowtow. They explain their purpose in coming, ask forgiveness and promise obedience. After long hours of persuasion, the bride's parents finally agree. Consequently, all members of the clan congratulate the couple, who kowtow to the clan's ancestors, to the village Fire God, and to the bridegroom's parents. A sumptuous banquet follows, guests and relatives dancing and singing with utter delight. ++

Ewenki Hunter's Wedding

The matrimony of Ewenki hunters includes three phases: courtship, betrothal and wedding. When the wedding is approaching, the bridegroom has to move his camp to a place neighboring to the bride's house, however far he lives. On the wedding day, the bridegroom take 10 reindeer as presents to the bride's house, accompanied by his parents, other relatives and friends. The the bride receives the bridegroom with a part of similar size and make up. When they meet, the bride and the bridegroom hug and kiss, and give each other the presents. Then everyone goes into the tent to enjoy a feast. The wedding doesn’t begin until the night after everyone finished feasting. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China ~]

Ewenki region in the summer

The Ewenki wedding has traditionally been held outdoors, not indoors. At the wedding site, in a river valley, the ground is cleared and a bonfire named the "Fire of Joviality" is lit. People cluster round the bridegroom and the bride, push them from the tent towards the bonfire. People gather round the bonfire in a half-circle, and an old man who presides over the wedding starts the ceremony. He pours wine into two birch bark cups, and hands them to the bridegroom and the bride. They spill a cupful of wine into the fire, to show their respect to the Fire God. Then they propose a toast to the parents, with the groom toasting the bride’s parents and the bride doing the same to groom’s parents. ~

The newlyweds then hug and kiss, and everyone in attendance sings and dances in a circle, hand in hand, throughout the night. The Ewenki call this kind of singing and dancing “the Dance of the Fire of Joviality". The movements are grand and powerful. The dancers raise their arms and twist their waist and leap. Following a lead singer, everybody joins in the chorus. The singing goes with the dancing, and the dancing goes with the singing, quick or slow, high or low. Everyone sings and dancies and no one wants to stop until they have enjoyed themselves thoroughly and are completely exhausted. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China]

Ewenki Houses and Food

The traditional Ewenki house is an umbrella-like teepee composed of twenty-five to thirty poles covered with birch bark and deerskin. The side with a door is used as the living room. The other three sides have platforms for sleeping. In the center is a fire pit with a pot hanging over it. An opening at the top allows for ventilation. The tablet of the ancestors is attached to the top of the central wooden column. In hunting areas, houses are cube-like log cabins. The walls are built by piling up logs, and the roof is made of birch bark. In some areas, Ewenki live in a Mongolian-style yurts (gers)made of felt or hide. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

Ewenki have traditionally consumed a meat-based diet, with copious amounts of reindeer meat, venison and mutton, with some beef, pork and wild boar meat, supplemented by grains, such as Chinese sorghum, corn, millet, oats, and buckwheat. Vegetables don’t grow so well in their harsh environment and are less frequently eaten.

Ewenki have traditionally enjoyed milk tea and stewed meat and delicacies such as reindeer meat, venison, elk-nose meat sausages in the hunting areas. They are particularly fond of roasted meat. “Cooked meat held in hand" is very popular during festivals. The meat, attached to the bone, is chopped in big pieces and is half-cooked with a little salt. When they eat it they hold a big piece with their hand. They also like gruel with milk, which is also a sacrificial offering to the gods.

Reindeer: Boat in the 'Sea' of Forests

riding reindeer

Reindeer are commonly called the “nondescript animal” in China because they have horse-like head, deer-like antler, donkey-like body and cattle-like hoofs, but they are different from each of these four animals. Reindeer are well adapted for cold weather. They are fond of eating moss, and manage well in remote mountainous forests, swamps, or deep snow. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China ~]

The reindeer in northern China are believed to have originated from wild animals in northern Russia. They were caught and domesticated by hunting groups in China and Russia such as the Ewenki and Oroqen and used in a number of ways in daily life. The Ewenki became the last ethnic group in China to breed and use reindeer after the Oroqen gave up the reindeer in favor of the horse.

Reindeer are called 'Erlun' in the Ewenki language. They generally measure around two meters in length and one meter in height, and weigh from 100 kilograms to 150 kilograms. The colors of their hair includes a dust-color, white, black and gray. Their tails are usually short. There is a long tuft of hair under the neck. Males are larger and taller than females. Their life-span is generally 15 years to 20 years. Most of the females in deer family have no antlers, but among reindeer both sexes grow a pair of branched antlers. The size of the antlers and amount of the branches vary according to age. The antlers fall off in the autumn and grow again in March or April the next year. The reindeer are quite valuable to the Ewenki and have traditionally been their main source of income and provided them with meat and milk. The skin can be tanned to leather and the antlers and genitals are used make prized oriental medicines.

Reindeer are meek by nature. They never kick or bite people and are relatively easy to raise. They are usually raised by women. It is not necessary to enclose them with a fence, or feed them. You can just put them out to graze. They leave the campsites when night comes, gathering in herds and grazing in the forests, and come back at dawn. They don't leave in the daytime. The reindeer are good at finding food. Even in the winter, when the mountain paths are sealed by snow, they can also use the broad forepaws to dig up into the snow, as deep as one meter, to look for mosses to eat. Reindeer like salt. Their masters can knock on the salt box if they want to use the reindeer. They will follow the sound and come.

Reindeer are very strong. They can bear a burden of more than 40 kilograms and cover more than 32 kilometers per day. They are indispensable in the productive and daily life of the Ewenki hunters, because their relatively light weight and broad hoofs allow them to walk for a long time in deep snow, swamp or dense forest. People use the reindeer to transport hunted animals and articles for daily use, such as cookers, foodstuff, clothes, and fabric and birch bark that can be used to make tents. The Ewenki love their reindeer dearly. Each reindeer has a name and a wooden or cooper bell so that it can be found easily. The Ewenki never give heavy things to pregnant reindeer or baby reindeer to carry, and they won't milk them when the reindeer are sweaty, to avoid abortion and disease.

Ewenki Encampment

birchbark teepee

Jonathan Kaiman wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “The encampment where Suo lives, in a patch of sparse forest in the Greater Hinggan mountain range, is an assemblage of four wedding party-style tents near a shallow stream. There are no power lines or cellphone service. Nothing lies between the encampment and the border with Siberia except a 50-mile swath of birch trees and frozen ponds. Suo and four others live there, along with a herd of 400 reindeer, most of them owned collectively by those at the resettlement site. [Source: Jonathan Kaiman, Los Angeles Times, December 4, 2011]

Day-to-day life at the encampment, which is packed up and moved every few months, is guided by simple survival. The herders spend many of their waking hours chopping firewood in preparation for the winter, when the temperature can reach 40 degrees below zero and snow piles up waist-high. The interior of Suo’s tent remains dark during even during the day and smells strongly of wood smoke. Old rags and fresh meat hang side by side in the tent from lines strung across its metal frame. Plastic trinkets mingle with animal bones on a crude wooden shelf in the corner

The herders subsist on reindeer milk, a staple of the Ewenki diet, and whatever game they can find in the woods, supplemented by garlic and cabbage from the city. Squirrel is a special treat, and occasionally one of the hunting dogs nabs a roe deer; the herders immediately eat its liver raw and save the rest for later.”We’ve always depended on our hunting for survival,” said Ma Lindong, 45, a herder who is married to one of Suo’s nieces. “If we don’t have that, then what else do we have?”

Ewenki Culture: Music, Dance, Sports

Myths, fables, ballads and riddles form their oral literature. Old hunters are regarded as master storytellers, weaving tales about ancient and modern heroes in their fight against the harsh environment and wild animals. Embroidery, carving and painting are among the traditional lines of modeling arts as commonly seen on utensils decorated with various floral designs. They have traditionally carved wooden sculptures and toys for trade.

Ewenki excel at making and designing a variety of things from birch bark. Painting on the birch bark is a special talent of the Ewenki. Ewenki birch bark carvings feature all kinds of beasts and animals and are often made as toys for children. They decorate their birch bark containers with various kinds of beautiful patterns.

The Ewenkis excel in horsemanship. Boys and girls learn to ride on horseback at six or seven when they go out to pasture cattle with their parents. Sports like lassoing and horse racing are often connected with nomadic life. Girls are taught to milk cows and take part in horseracing at around ten, and learn the difficult art of lassoing horses when they grow a little older.

The Ewenkis excel in horsemanship. Boys and girls learn to ride on horseback at six or seven when they go out to pasture cattle with their parents. Sports like lassoing and horse racing are often connected with nomadic life. Girls are taught to milk cows and take part in horseracing at around ten, and learn the difficult art of lassoing horses when they grow a little older.

Ewenki kids have traditionally gathered to shoot arrows, do high jumping, pole vaulting and long jumping and ski. All these things are viewed as skills that will help them be skilled hunters and herdsmen when they are adults. Horse lassoing is a popular festival competition. Around1,300 years ago, ancestors of the Ewenki, called Shiwei, made primitive skis. The skis used today by the Ewenki for hunting are but an improved versions of the Shiwei “snow-sliding boards." Children use pieces of sheep ankle bone, dyed different colors, to play f horse racing game.

Ewenki folk songs have been described as slow and unconstrained, evoking the vast expanses of the grassland. Dancing styles vary according to region and occasions but they often feature foot movements executed in a forceful, vigorous and highly rhythmic style. The Ahanba is performed by women at wedding ceremonies. There are no accompanying instruments. The tempo is set by singers' voices. Groups with two to four dancers begin by crying softly, “A-Han-Ba, A-Han-Ba," while swinging their arms. Then they turn face to face and bend their knees. As the tempo gradually increases, the movement of their feet intensifies with the the rhythm until it reaches a frenetic climax. Another dance, performed by two young men, imitates a wild boar hunt. One man is a hunter; the other wears a wild hog costume. With their hands behind their back, they ram each other with their shoulders while snorting and roaring. A group led by a singer encircles the two actors, moves around a bonfire, and dances while singing. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Ewenki Folklore

C. Le Blanc wrote in the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” “The origin of mankind is explained as follows in an Ewenki myth: After the creation of the sky and the earth, the god Enduli made 10 men and 10 women from the skeletons of birds. Encouraged by his success, he planned to make more men and women, 100 of each. He made men first, but in the process of his great work, he nearly ran out of bird skeletons. He had to use soil as a supplement to fashion the women. As a result, the women were weaker, a part of their body being made of soil. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

Ewenki mittens

“The Ewenki have a special reverence for fire. This may be related to their tough Nordic environment and is reflected in one of their main myths. A woman was injured by a shower of sparks from the household hearth. Angered by her pain, she drew her sword and stabbed violently at the hearth until the fire died out.

The following day, she tried in vain to light a fire. She had to ask for a burning charcoal from her neighbor. Leaving her house, she found an old woman crying miserably, with a bleeding eye. Replying to her queries, the old woman said: “It was you who stabbed me blind yesterday." The woman, suddenly realizing what had happened, kowtowed to the Fire God and asked for her forgiveness. The Fire God finally pardoned her. From then on, she never failed in lighting a fire. Up to the present, the Ewenki throw a piece of food or a small cup of wine into the fire as an offering before meals. However, sprinkling water on a fire or poking a fire with a sword during meat roasting is taboo. ++

Last Quarter Moon; Novel About the Ewenki

“The Last Quarter of the Moon”—the saga of the Evenki clan of Inner Mongolia— is the first novel from award-winning Chinese novelist Chi Zijian to be translated into English. Kelly Falconer wrote in the Financial Times, “It is an atmospheric modern folk-tale” about “nomadic reindeer herders whose traditional life alongside the Argun river endured unchanged for centuries, only to be driven almost to extinction during the political upheavals of the 20th century. Their history is recounted by the 90-year-old, unnamed widow of one of the clan’s last great chieftains. Her ethereal presence and memory, and strength of will, allows her to speak for the tribe, breathing life into their collective memories. [Source: Kelly Falconer, Financial Times, January 18, 2013]

“The story is full of allegory. There is the fire that is passed from one generation to the next; the cycles of life and death; and the “coexistence of mankind and the Spirits”. The clan’s reindeer are central to their lives and “were certainly bestowed upon us by the Spirits, for without these creatures we would not be”. Chi channels, Shaman-like, the sentiment, emotions and experiences of another, much older woman (Chi was born in 1964). Inevitably the wider world intrudes: in 1965 the clan votes on whether or not to “resettle”, leaving their mountains for a newly created township away from their shirangju (open-roofed teepees), where they fall asleep looking at the stars. Everyone yields to the communists’ persuasion, apart from the narrator: “My body was bestowed by the Spirits, and I shall remain in the mountains to return it to the Spirits.” Her simple-minded grandson stays behind to look after her and their few reindeer.

“The others realise their mistake when reindeer start to die in captivity. The communists believe the precious animals to be like ordinary domesticated beasts: they should eat “tender branches in the summer, and hay in winter. They won’t starve”. The Evenki protest: “Do you take reindeer for cattle or horses? Reindeer won’t eat hay. They can forage for hundreds of different foods in the mountains. If you make them eat just grass and branches, their souls will suffer and die!”

Ewenki embroidered gloves

“This nomadic clan has not kept pace with the world, and their lives (like those of their reindeer) are irretrievably disrupted by the forces of modernity. The pace of this tale is slow but certain, as though the story unfolds to the beat of an ancient, sonorous drum. The animistic Evenki have a symbiotic relationship with nature, and Chi’s narrative is decorated with descriptions of the forests and the mountains, of the flora and fauna: Autumn resembles “a thin-skinned person. If the wind utters a few less than complimentary words about him, he pulls a long face and beats a retreat”; there are falling leaves dancing “like yellow butterflies in the forest” and a snow-white fawn, which “resembled an auspicious cloud that had just fallen to the earth”. The Evenki survive famine, disease, war and reform, drownings, lethal snowstorms and accidental shootings. The one thing they cannot endure is displacement. The book ends with a glimpse into their uncertain future, “deeply shrouded in death’s shadow.”

“”The Last Quarter of the Moon” is the English-language title. In Chinese it is “The Right Bank of the Argun,” a hint that the story is based on fact. Chi relates how she grew up in this landscape. “As a child entering the mountains to fetch firewood, more than once I discovered an odd head-shape on a thick tree trunk. Father told me that was the image of the mountain spirit Bainacha, carved by the Oroqen [another nomadic clan]”. Latterly, Chi researched her book by staying in an Evenki encampment. She concludes: “I felt that I had at last found the seed for my novel ... The vast stretch of forest I possessed as a child would serve as its seedbed, and I was confident that this seed would sprout and grow in it.” Chi was right to be confident. This is a fitting tribute to the Evenki by a writer of rare talent.

Book: “The Last Quarter of the Moon,” by Chi Zijian, translated by Bruce Humes, Harvill Secker]

Resettling the Ewenki

Jonathan Kaiman wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “The Ewenki are among hundreds of thousands of nomadic herders from the country’s northern hinterlands who have themselves been herded into permanent settlements. Government officials say their aim is to provide new opportunities for the nomads while protecting the environment from overgrazing and hunting. In some cases, relocations are a consequence of governmentbacked initiatives to excavate mines on herders’ grazing land, critics say. Officials say they are promoting diversity by bringing nomadic minorities into mainstream society, but the relocations are strictly carried out only on the government’s terms. [Source: Jonathan Kaiman, Los Angeles Times, December 4, 2011]

According to a 2007 report by Human Rights Watch on the resettlement of Tibetan herders, such relocations “often result in greater impoverishment, and — for those forced to resettle — dislocation and marginalization in the new communities.” “When changes happen to an ethnic group in this way, so quickly, this can be very painful,” said Bai Lan, a professor at the Inner Mongolia Academy of Social Sciences.

According to a 2007 report by Human Rights Watch on the resettlement of Tibetan herders, such relocations “often result in greater impoverishment, and — for those forced to resettle — dislocation and marginalization in the new communities.” “When changes happen to an ethnic group in this way, so quickly, this can be very painful,” said Bai Lan, a professor at the Inner Mongolia Academy of Social Sciences.

In 2003, one group of 200 Ewenki was forcibly relocated from their encampment to a “resettlement site” 120 miles away, on the outskirts of Genhe, a dilapidated riverside city. Government officials confiscated their hunting rifles and urged them to leave their herd of reindeer behind. Before they were resettled reindeer were used mainly to haul tepees and bedrolls on long expeditions to hunt for moose, bear and wild boar. Economic necessity has transformed them from beasts of burden into money makers: The herders now make a modest living selling their antlers for use in traditional Chinese medicine.

Ewenki Resettlement Site and the Loss of the Ewenki Way of Life

In the mid 2000s, most of the members of Suo’s tribe — about 231 people — were resettled in a village 50-square meter houses with modern conveniences such as cable television, toilets and central heating. Many make their living by selling antler products, some of them marketed online. Some make a living from tourism. The villagers are allowed to maintain herds of reindeer in five designated hunting grounds. [Source: China Daily February 5, 2009]

Jonathan Kaiman wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “The resettlement site, called Aoluguya, Ewenki for “grove of poplars,” has a different set of problems. The product of a multimilliondollar investment by the Genhe city government, the site looks more like a theme park than a community. Road signs describe it as a “Reindeer-herding Tribe Culture Tourism Zone.” Its perimeter is decorated with giant models of tepees, the Ewenkis’ traditional abode. [Source: Jonathan Kaiman, Los Angeles Times, December 4, 2011]

The government commissioned a Finnish consulting firm to design the site in the image of a Scandinavian hamlet. Its residents live in rows of freshly varnished lodges with frontyards and vaulted roofs. The homes’ interiors are spartan; most contain nothing more than a few beds, a stove and a television. “They wanted to attract foreigners, but the foreigners never come,” said Ao Rongbu, 63, a former herder who remains in the settlement because of a heart condition.

Aoluguya is plagued by poverty and alcoholism. Its residents survive by selling handicrafts during the summer, mainly knickknacks carved from reindeer antlers. “There’s nothing interesting about Aoluguya. There are no trees. There are no reindeer,” said He Xie, Suo’s 47-year-old son, slurring his words after a day of drinking. Much of Ewenki culture has been lost. The children are taught only Mandarin in school, and most can no longer speak their parents’ unwritten language, which is in danger of disappearing. [Source: Jonathan Kaiman, Los Angeles Times, December 4, 2011]

Many of the reindeer at the resettlement site starved to death in their first few weeks for lack of a type of lichen that grows only in the woods. “What upsets me is that, in the future, who will take care of the deer?” said Ma Rusha, a 55-yearold herder. “Young people are afraid that they’ll run into black bears and wolves. They’re not willing to stay here.”

The nomadic herders seem to enjoy some modern comforts. A few years ago, the government provided a pair of solar panels and ATV, enabling them to watch state broadcasts. Suo does not understand Mandarin, but the rest of the herders gather each night to drink liquor and watch the news. In the morning, they discuss international affairs as they fetch water from the stream. The herders have opinions about figures such as Microsoft founder Bill Gates. They are also huge NBA fans. Lichen for the reindeer has been growing scarce in the area surrounding the encampment, and the group will have to move soon to feed its herd. “Wherever there is food for the deer, that’s where we’ll go,” said Ma Lindong. As always, he said, they will bring the TV and the solar panels with them.

Ewenki Old-Timer Clings to Life Guided by Reindeer

Jonathan Kaiman wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Once her tribe’s best reindeer herder, Maliya Suo, a last link to the traditional Ewenki language and way of life, lives in an encampment in the woods in northeastern China. In her old age, Suo is taking on an even tougher adversary: the Chinese government. A member of the nomadic Ewenki community that lives primarily in China’s Inner Mongolia region, Suo has resisted the government’s effort to resettle her in the world of buildings, money and cars. [Source: Jonathan Kaiman, Los Angeles Times, December 4, 2011]

Suo, wanting no part of modern urban life, soon moved back to the woods, where she has been ever since. “The city doesn’t smell good,” said Suo, whose deep-set eyes are cloudy and who wears an old wool vest and a pink-and-beige patterned head scarf. She doesn’t speak much, and when she does it’s in a pained warble. Yet her manner conveys a matriarchal authority.

After Suo insisted on leaving the resettlement site, several family members said they had no choice but to follow because she was too old to live alone; exactly how old, nobody seems to know. “We go into the mountains because Maliya Suo is in the mountains,” said Zhang Dan, a 37-year-old craftsman. “Nobody is willing to move her.” Suo, who is thought to be over 90, is the last link to the traditional Ewenki language and way of life. She spends much of her time sitting on her bed or on the ground in the tent, munching on pine nuts and tending the fire.

Suo, whose husband was a talented hunter 12 years her elder, had seven children. Only two are still alive. Her eldest daughter, the first member of the tribe to attend college, drowned while drunkenly washing clothes in a shallow stream. A son died when his bladder burst after a drinking competition. Another son was shot dead in the woods, and two died of illness. Suo’s husband, whom she regularly accompanied on hunting trips, drank himself to death, family members said. In the old days, her main responsibility was to strap the game her husband killed onto the backs of reindeer and guide them back to camp. Now she looks after the members of the tribe who live with her in the woods.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Nolls China website, Donsmaps, Xinhua

Text Sources: 1) "Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China", edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company; 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China *\; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2022