MANCHU LIFE

Aksan, a famous Manchu singer

Traditionally, the Manchu were organized on the basis of patrilineal clans; marriages were arranged by parents; couples were wed when they were 16 or 17; and babies were kept in suspended cradles. The latter customs dates back to a time when the Manchu hunted regularly on horseback and suspended the cradles from tree branches so that wild animals would not get the babies while the parents were out hunting. During the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), Qing princes studied from 5:00am to 4:00pm. Their curriculum included lessons in Manchu, Mongolian and Chinese as well as riding, archery and martial arts. Sometimes they continued their studies until they were in their 30s. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Lin Yueh-hwa and Naranbilik wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “Mountain and forest hunting and gathering were more important subsistence activities in the past, but for many centuries the Manchu have been a sedentary agricultural people. Sorghum, maize, millet, soybeans, and tobacco are basic crops, along with fruit growing. Animal husbandry is part of the rural economy, particularly the raising of pigs. In the 1990s, more than 80 percent of the Manchu living in Liaoning, Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Hebei were engaged in agriculture. The remainder of the population was in industry and a variety of urban jobs. Forestry and lumbering are also part of the present economy. There was a merchant class in past centuries, although during the Qing dynasty the Manchu were forbidden to engage in trade. Even then the Manchu held an official monopoly on ginseng, a medicinal root native to the area. Business activities have begun to reemerge since the economic reforms of the early 1980s. |~|

During the Qing dynasty, most of the Manchu, aside from members of the imperial clan or those in the thirty-one grades of the aristocracy, were “bannermen," who received land and stipends from the government. The “banners" were military forces who together with their families were assigned to various locations within the empire. Most were assigned to areas in and around major cities, particularly Beijing. Within the homeland area, the Manchu continued as farmers, theoretically banned from engaging in trade or artisan labor. The main division of labor in the countryside was along sex lines, with household chores undertaken by the women and most of the agricultural work or side occupations engaged in by men. In the twentieth century, some of the urban Manchu became peddlers or workers, and some entered the arts and professions.

Manchu fashions included riding boots and royal robes with flared cuffs and narrow sleeves (not wide Chinese-style sleeves) and slits for riding horses even though they often weren't worn on horseback. Manchu men have traditionally worn a long gown and mandarin jacket. The cheongsam, a woman’s dress associated with the Chinese, originated with the Manchus. The Manchu cheongsam was loose and reached to the ankle (See Clothes). In the old days female members of the Manchu elite didn't cut their hair, their feet remained unbound and the nails of their third and forth fingers were allowed to grow, sometimes to a length of over four inches.

See Separate Articles ETHNIC GROUPS IN NORTHERN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; MANCHUS: IDENTITY, RELIGION AND LANGUAGE factsanddetails.com; MANCHUS — THE RULERS OF THE QING DYNASTY — AND THEIR HISTORY factsanddetails.com ; QING (MANCHU) DYNASTY (1644-1912) factsanddetails.com; QING LIFE factsanddetails.com; XIBE MINORITY factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Nationalities in Northeast China kepu.net.cn ;Book Chinese Minorities stanford.edu ; Chinese Government Law on Minorities china.org.cn ; Minority Rights minorityrights.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Ethnic China ethnic-china.com ;Wikipedia List of Ethnic Minorities in China Wikipedia ; China.org (government source) china.org.cn ; Paul Noll site: paulnoll.com ; Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science Museums of China Books: Ethnic Groups in China, Du Roufu and Vincent F. Yip, Science Press, Beijing, 1993; An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of China, Olson, James, Greenwood Press, Westport, 1998; “China's Minority Nationalities,” Great Wall Books, Beijing, 1984; “Seeking Eternity; The Manchus” by Ai Jun (Yunnan Education Publishing House, China, 1995)

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Manchus” by Pamela Kyle Crossley Amazon.com; “China's Last Empire: The Great Qing” by William T. Rowe and Timothy Brook Amazon.com; “The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China by Mark C. Elliott Amazon.com; Culture: “Reorienting the Manchus: A Study of Sinicization, 1583–1795" by Pei Huang Amazon.com; “The Qing Dynasty and Traditional Chinese Culture” by Richard J. Smith Amazon.com; “Traditional Manchu Archery of the Qing Imperial Guard” by Scott M. Rodel Amazon.com; “Chinese Dress: From the Qing Dynasty to the Present Day” by Valery Garrett Amazon.com; “In the Mood for Cheongsam: A Social History, 1920s-Present” by Lee Chor Lin and Chung May Khuen Amazon.com; “Encyclopedia of Chinese Traditional Furniture, Vol. 2: Ethnical Minorities” by Fuchang Zhang Amazon.com

Manchu Marriage and Family Customs

Manch bride and maid

Monogamy has always been the norm among Manchus. Traditionally, marriages were arranged by parents and couples were wed when they were 16 or 17. A bride price was paid and reciprocated with gifts of wine, jewelry, clothing and pork to the groom’s family. The dowry was regarded as the bride’s property. In the countryside, many Manchu still live in three-generation households. In the cities, nuclear families are the norm.

On the wedding day, the bride had to sit the whole day on the south "kang", an act inaugurating "future happiness." When night fell, a low table with two wine pots and cups would be set. The bride and bridegroom would, hand in hand, walk around the table three times and sit down to drink under the light of a candle burning through the night on the south "kang". They were congratulated amid songs by one or several guests in the outer room. Sometimes the ceremony was marked with well-wishers casting black peas into the bridal chamber before they left the new couple. On the fourth day, the newlyweds would pay a visit to the bride's home. [Source: China.org]

Babies are kept in suspended cradles. The customs dates back to a time when the Manchu hunted regularly on horseback and suspended the cradles from tree branches so that wild animals would not get the babies while the parents were out hunting.

Manchu Houses and Kangs

In the old days the Manchu were organized on the basis of paternal clans. Now they are organized on the basis of villages and towns. Traditionally, the Manchus lived in houses that were similar to those used by Han Chinese. A typical house had three divisions: a central room used as a kitchen and two quarters that served as sleeping and living areas. The sleeping rooms were heated by kangs, brick beds that be could heated in the winter and were laid against the west, north and south walls. Warm in the winter and cool in the summer, the houses were open to south and west and usually had a three-generation family with seven or more people living in it.

Many people in northern China sleep on or around a kang, a traditional brick bed or concrete platform, built over a stove, oven or fireplace which is heated with coal, wood or animal dung and provides warmth in the winter. Kangs are usually covered with cotton mattresses and colorfully embroidered quilts. Houses south of the Yangtze generally don’t have kangs or central heating.

Houses of the Manchus were built in three divisions, with the middle used as a kitchen and the two wings each serving as bedroom and living room. By tradition, the bedroom had three "kang", which were laid against the west, north and south walls. Guests and friends were habitually given the west "kang", elders the north, and the younger generation the south. Traditionally, to the west of the kang was an altar used to hold sacrifices for ancestors. With windows generally open to the south and west, the houses stayed warm in winter and cool in summer. [Source: China.org]

Manchu Customs and Taboos

The Manchu have a long tradition of honoring the elders and respecting the ancestors. Whenever there was festival or a big event such as marriage, child birth, building of a new house, or promotion Manchu people would carry out large-scale ancestor worship ceremonies to pray for good fortunes. [Source: Chinatravel.com ]

Manchu women and children in front of traditional houses

A variety of manners observed by the Manchus show respect towards the elderly. Children were required to pay formal respects to their elders regularly, once every three to five days. In greeting their superiors, men were required to extend their left hand to the knee and idle the right hand while scraping a bow, and women would squat with both hands on the knees. Between friends and relatives, warm embraces were the commonest form of greeting for all men and women. [Source: China.org ]

Manchu people have a special fondness for dogs. Beating or killing dogs are strictly forbidden. The Manch do not eat meat of dogs, do not wear dogskin hats or wear clothes with dogskin cuffs. Do not chase or scold dogs before a Manchu host. Never say anything bad about dogs, or your Manchu host might think you are insulting him and ask you to leave immediately. Additionally, Manchu are not allowed to hit pied magpies and crows, or to tie livestocks on the Suoluo tree poles. See Nurhachi and Respect for Dogs and Crows Above. The Manchu views the West as superior. It is a taboo for common people, especially young people to sit on the west Kang, and women are even more strictly forbidden to give birth to her child on the west side of Kang.

In the old days female members of the Manchu elite didn't cut their hair, their feet remained unbound and the nails of their third and forth fingers were allowed to grow, sometimes over four inches long.

It is not uncommon for teenage girls to smoke pipes. Elderly people like to smoke long pipes.

Steamed Buns and Other Manchuria Foods

A favorite traditional Manchu meal consisted of steamed millet or cakes of glutinous millet. Festivals were traditionally celebrated with dumplings, and the New Year's Eve with a treat of stewed meat. Boiled and roast pork and Manchu-style cookies were table delicacies. [Source: China.org china.org ]

The Manchuria steamed bun is a traditional food of the Manchus and is now popular snack and carry-out item in northeast area—and for that matter all of China and large parts of Asia. The Manchus called these buns: steamed bread and steamed stuffed bun. A variety of foods are referred to by the name of Manchuria bun. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

Manju

Manchus enjoy many kinds of pastries and cakes. Among them are: 1) Sanzi made from kneaded buckwheat flour or glutinous broomcorn millet flour dough rolled into threads and steamed in lattice cooker or fried with oil, and then mixed with bittern sauce and made into soup. When the Manchus have fetes, Sanzi is often offered. 2) Tamping cakes are made from glutinous broomcorn millet, glutinous millet or polished glutinous rice steamed in a lattice cooker. When prepared with glutinous cooked rice, water is poured on the rice, which is then placed on a flag stone and hammered into dough. The dough can be rolled into various cakes. They are often with sugar or honey. ~

3) Cakes with sauce are made from up glutinous broomcorn millet flour, glutinous millet or polished glutinous rice scooped into a cloth bag mixed with some sauce into the container, steamed in a lattice cooker and cut into diamonds or blocks, then. They have a smooth and soft texture in addition to a good flavor. 4) Scattering cakes are made with glutinous rice and steamed in a lattice cooker. According to the size of the lattice cooker, a thin layer scattered beans is alternated with a layer of glutinous rice flour. After the first layer is cooked a second layer is made. The process is repeated until the desired number of layers is prepared. 5) Candied fritters are cooked in the same fashion as tamping cakes with cooked rice placed on a flag stone and tamped repeatedly into dough. Afterwards, the dough is dipped into cooked bean flour, kneaded into bars and ,after frying, cut into blocks and covered with a sprinkled of cooked bean flour or sugar. ~

6) Glutinous millet buns are made of glutinous millet mixed with other ingredients. According to the different production seasons and different ingredients, the buns can be classified into: bean flour buns (offered in spring, made of pulverized glutinous millet and other things and baked) and linden leaves bun (offered in summer, linden is a kind of plant whose egg-shaped leaves are like hibiscus). To make linden leaves buns: knead the flour into dough and roll the dough into skins. After bean stuffing is placed in the skins, the skins are bound together with linden leaves and steamed in a lattice cooker. for heating. ~

Porter carrying snacks on his head

There are also perilla leave buns, gold cakes, sun cakes, cool cakes, glutinous millet bun (offered in autumn, with bean sauce) and Lvdagun (a pastry made of steamed glutinous millet flour mixed with sugar). Perilla leave buns are made using the same methods as the linden leaves bun. The only difference is that perilla leaves are used instead of linden leaves. ~

The traditional Chinese banquet served today has its origins the Manchu court feast of the Qing Dynasty. Said to have been introduced during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor, it mainly employs Manchu baking and braising and Han frying. The feast includes many famous dishes and cakes. There are over 200 dishes in all, of which 134 dishes are hot and 48 are assorted cold. There are also dozens of cakes. In Qing times, the raw materials for the dishes often came from articles of tribute. Delicacies of every kind such as mountain food, seafood, rare animals, fresh vegetables, and rare fruits were found in this feast. The dishware was also delicate and mainly made up of gold cup, silver plate, jade calyx, ivory chopsticks and so on. After the Revolution of 1911, the dishware and food has been simplified. ~

Cheongsam and Manchu Clothes

To meet their original needs of hunting, riding and fighting, traditional Manchu clothes had a large front, no collar and extended narrow horse-hoof-shaped or so-called sword sleeves, which could protect the hands when fighting. Later this kind of garment became their formal dress. A typical robe of this sort worn by a high class person was decorated with gold-thread embroidered with designs of dragons, sea waves and clouds. A rhombus-shaped cloak served as an ornamental collar and was around the neck and on the shoulders.

A Manchu Robe with Python Design is on display at the Shanghai Museum. According to the museum: Robes embroidered with python design derived from the early male clothes style of the Manchu, retaining the original features while making a few changes. The Manchu lived on horseback. The horse hoof shaped cuff, also known as arrow cuff, can protect the hand when shooting arrows. Later formal dress adopted this feature and therefore a special action of sleeve flicking was involved when Manchu people gave a salute. The reformed Manchu embroidered robe was once the official uniform of the Qing dynasty. [Source: Shanghai Museum]

Manchu girl in the 1860s

The cheongsam, a women’s dress associated with the Chinese, originated with the Manchus. Known as a "qi pao" in Mandarin, the cheongsam is a tight form-fitting Chinese dress with thigh-high slits and a high-collar. Traditionally a dress worn by Manchu women, it received some international exposure in the Suzie Wong film. The slit is supposed to rise no higher than mid thigh. If it goes any higher it is considered sluttish. The cheongsam worn by Manchu women was loose and reached to the ankles. It evolved into a tight-fitting dress extending below the knee, with a high neck, narrow sleeves, slender waist and two slits, on the left and right, buttoning down the right side. The dress was known for showing off the figures of eastern women.

Manchu men have traditionally worn a long gown and mandarin jacket. The traditional costumes of male Manchus are a narrow-cuffed short jacket over a long gown with a belt at the waist to facilitate horse-riding and hunting. Women wore earrings, long gowns and embroidered shoes. Linen was a favorite fabric for the rich; deerskin was popular with the common folk. Silks and satins for noble and the rich and cotton cloth for the ordinary people became standard for Manchurians after a period of life away from the mountains and forests. Following the Manchus' southward migration, the common people came to wear the same kind of dress as their Han counterparts, while the Manchu gown was adopted by Han women generally. [Source: China.org |]

In the past, the Manchu often wore a skullcap with peaked top and broad bottom, sewed from six parts. This "six parts unification" skullcap featured three-centimeter-wide or had brocaded margin with no brim. The hat adopts with a black flat satin surface were worn in winter and spring while hats with black gauze were worn in summer and autumn. A black or red knot at the top of the hat was called the "abacus knot". Under the brim, in the middle, was the " cap center" sometimes made of pearl, agate, silver or glass. This kind of hat can be traced to the period when Ming Tai Zu Zhuyuanzhang was in Emperor. The six sewed up parts symbolized the six sides of the universe and represented unification. After Manchu took over China, the "unification" skullcap became popular among Han Chinese as well as Manchus. Nowadays, we can still see those caps in TV dramas set in the Qing Dynasty and the period of the Republic of China.

See Cheongsam (Qi Pao) Under TRADITIONAL CLOTHES OF CHINA factsanddetails.com

Manchu Hairstyles

Manchu males let the back part of their hair grow long and wore it in a plait or queue. During the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) the queue became the standard fashion throughout China, eventually becoming a political symbol of the dynasty.Women coiled their hair on top of their heads. [Source: China.org |]

In the Qing era, Manchu women wore their hair in a broad and long fashion, somewhat like a fan and sort of like a crown. At that time, most Manchu girls, like Manchu boys, had their hair shaved off around the head in the childhood, with the hair on the back of the head left and cued into braid. It was not until they grew up that Manchu women could let their hair grow. After marriage, Manchu women rolled their hair into tray-shaped hairdos, shelf-shaped hairdos, two halves hairdo and others.

The two halves hairdo was the typical. In it, hair on top of the head was divided and tied into two locks, with each lock cued into a hairdo. The hair on the lower part of the head was cued into a "swallow-tailed" long and flat hairdo. A hair clasp called " the flat pane"— which was 20 or 30 centimeters in length and two or three centimeters in width—was inserted into the hairdo. At festivals, or when welcoming the guests, women were expected to wear traditional crown-style hairdos. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

The bone of the crown-style Manchu women’s hairstyle was made up of iron thread or bamboo strip while the cover of the crown was made of cyan flat satin, cyan wool or cyan gauze. The crown was fan-shaped, with a length was over 30 centimeters and a width over 10 centimeters. When worn, the crown served as frame for the hairdo and was often decorated with patterns, embroidery, jewels, flower, ribbons or tassels. This kind of headgear was mostly worn by upper class Manchu women. Ordinary Manchu women only wore it on their wedding day. The broad and long crown restricted the movement of neck and required women to keep their bodies straight. ~

Manchu "Banner Shoes"

The "mandarin shoes" of Manchu women were also very special. Known by the name "chopine", they were embroidered and came in two main types: "flowerpot-shaped soles" shoes and "horse-hoof soles" shoes. These wooden-soled shoes featured high heels around 5 to 10 centimeters in height, with some reaching the height of 14-16 centimeters and the highest around 25 centimeters. Generally, the heels were wrapped in white cloth and were inlaid in the middle. The heels had two shapes: the first one was broad at the top and narrow at the bottom, forming the shape of a trapeziform flowerpot. The second one was narrow at the top but broad at the bottom and flat in front but round in the back, forming a horse-hoof shape. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

The upper parts of these "flowerpot shoes" and "horse-hoof shoes" were decorated with cicadas and butterflies. Parts of the wooden heels were ornamented with embroideries and strings of beads. On the tips of some shoes, were silk thread-braided tassels that could touch the ground. The wooden soles with high heels were very solid. Often when the upper part of the shoe wore out but the soles were still intact and could be used again. Chopine with high heels were generally worn by upper class young women over the age of 13 years old. Older women wore shoes with flat wood soles that were were called "flat sole shoes" The fronts of these carved to facilitate walking. These are not worn now. ~

The Manchu have a long history of "getting shoes from whittling wood" custom. About the origin of this kind of shoes, there are a lot of opinions. According to one opinion, in the past, Manchu women often went into the mountains to collect wild fruits and mushrooms. To protect themselves from the biting of insects and snakes, they bound a wood block onto their shoes and later developed making them into a handcraft and raised the height of the soles. There is another opinion. Some say that the ancestors of Manchu imitated white cranes and bound tree branches to their shoes to cross a muddy pit and recapture the city occupied by an enemy. To remember this event, Manchu women began to wear high-heel wooden shoes and passed the tradition to their families. The shoes became more and more delicate and finally turned into what they look now. ~

Famous Manchu Writers, Scientists and Cultural Figures

Since 1949 Many Manchu writers and artists have gained fame throughout China since liberation. Cheng Yanqiu was a distinguished Manchu Beijing Opera singer as well as a patriot. During the Japanese occupation he quit the stage and returned to a quiet life on the western outskirts of Beijing. But soon after the national liberation of the country, he plunged himself into the work of training young opera singers. [Source: China.org |]

Lao She, widely known as a patriotic writer and people's artist, was born into a poor Manchu family and had tasted all the bitterness of life in his childhood. Before liberation he wrote Camel Xiang Zi (or Rickshaw Boy) to make a thorough critique of the old society. During the Japanese occupation he founded the National Writers' and Artists' Resistance Association, uniting and organizing Chinese writers and artists. He continued to write novels after liberation. From 1950 to 1966, he wrote more than a score of plays including Dragon-Beard Ditch, A Woman Shop Assistant and Teahouse, winning wide acclaim among the people. |

“A Dream of Red Mansions” written in the 18th century by the Manchu writer Cao Xueqin is a classic that occupies a prominent place in the history of world literature. With its story drawn from the life of a Manchu noble family, the novel gives incisive analysis and exposure of all the decadence of the Manchu ruling class. By dissecting China's feudal society, the author brought the country's literary expression to an unprecedented height. Zhao Lian's Xiao Ting Za Lu (Random Notes at Xiaoting), a true account of the events, rites, personalities and institutions of the early Qing Dynasty, was a work of academic value for the study of the history of the Manchus and Mongols. |

Also outstanding among the Manchus were many works by women writers. These include Qin Pu (Music Score) by Ke De, Hua Ke Xian Yin (Leisurely Recitation of Poems by the Flower Beds) by Wanyan Yuegu, Xiang Yin Guan Xiao Cao (Poems from Xiangyin Pavilion) by Kuliya Lingwen, and Tian You Ge Ji (Poems Written in Tianyou Pavilion) by Xilin Taiqing (Gu Taiqing). Her Dong Hai Yu Ge (Song of East Sea Fishermen) won her reputation as the greatest poetess of the Qing Dynasty. |

The Manchu people have produced many works of scientific and cultural significance in China. These include Shu Li Jing Yun (Essence of Mathematics and Physics), Li Xiang Kao Cheng (A Study of Universal Phenomena) and Huang Yu Quan Lan Tu (Complete Atlas of the Empire) compiled during the reign of Emperor Kang Xi. Man Wen Lao Dang (Ancient Archives in Manchu), Man Wen Tai Zu Shi Lu (A Manchu Biography of the Founding Emperor) and Yi Yu Lu (Stories of Exotic Lands) by Tu Lichen are among the famous works written in the early years of the dynasty, while Qing Wen Qi Meng (Primer of Manchurian), Chu Xue Bi Du (Essential Readings for Beginners), Xu Zi Zhi Nan (A Guide to Function Words) and Qing Wen Dian Yao (Fundamentals of Manchurian) are important works in the study of the Manchu language. [Source: China.org |]

Manchu Folklore Music and Dance

The Tale of the Nisan Shaman holds an most important piece of Manchu literature. It tells the story of how Nisan Shaman helped revive a young hunter. The story is also popular among the Xibe, Nanai, Daur, Oroqen, Evenk and other Tungusic peoples. Famous Chinese Manchu stories include “The Tale of Heroic Sons and Daughters”, “Song of Drinking Water” and “The Collection of Tianyouge. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Octagonal drum is a type of Manchu folk art that was very popular among bannermen, especially in Beijing. It is said that octagonal drum originated with the snare drum of the Eight-banner military and the melody was made by the banner soldiers who were on the way back home from victory in the battle of Jinchuan. The drum is composed of wood surrounded by bells. The drumhead is made by wyrmhide with tassels at the bottom. The colors of the tassels are yellow, white, red, and blue, which represent the four colors of the Eight Banners. When artists perform, they use their fingers to hit the drumhead and shake the drum to ring the bells. Traditionally, octagonal drum is performed by three people. One is the harpist; one is the clown who is responsible for harlequinade; and the third is the singer.

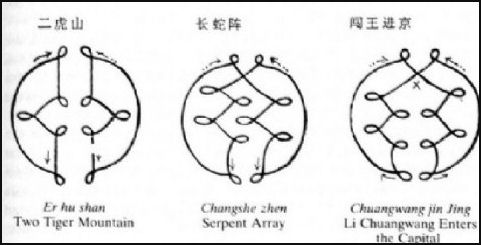

Yang ge patterns

"Zidishu" is the main libretto of octagonal drum and can be traced back to a type of traditional folk music called the "Manchu Rhythm". After the fall of the Qing dynasty, use of octagonal drum gradually decline however crosstalk — a kind of Chinese comedy — still uses octagonal drums. Ulabun is a form of Manchu storytelling entertainment which was traditionally performed in the Manchu language.

Old Manchu people — and old Chinese too — like to do the yang ge (yangge or yangke) a traditional northern Chinese folk dance accompanied by singing, drums and gongs and featuring colorful fans, which are held over the head. Developed as a fertility dance by farmers planting in their rice fields, it was introduced to all parts of China by the People's Liberation Army as part of campaign to its win supporters in World War II and was popular in the 1950s and allowed in the Cultural Revolution. Today it is most often seen in Beijing and other cities in the north.

See Yang Ge and Folk Dancing in China Under CHINESE DANCE factsanddetails.com

Traditional Manchu Sports

An ethnic group originally living in forests and mountains in northeast China, the Manchus excelled in archery and horsemanship. Children were taught the art of swan-hunting with wooden bows and arrows at six or seven, and teenagers learned to ride on horseback in full hunting gear, racing through forests and mountains. Women, as well as men, were skilled equestrians. Jumping onto galloping horses from one side or onto camels from the rear was the most popular recreational activity among the Manchus. Another favorite sport was horse jumping in celebration of bumper harvests in the autumn and on New Year holidays at the Spring Festival.[Source: China.org |]

There are many sports and entertaining activities enjoyed by the Manchu. Skating is also a long established sport enjoyed by the Manchus, as it is by the whole Chinese people. In the Qing Dynasty before the mid-19th century, skating was even undertaken by Manchu soldiers as a required course of their military training. Pole climbing, swordplay, juggling a flagpole, and archery on ice are the more interesting sports of the Manchu people. "Walking on snow" and "picking pearls" are two popular festival sports of them. "Walking on snow" is a kind of traditional woman sports. The participants wear Cheongsam and mandarin shoes to take part in walking race. It is called "walking on snow", because walking with mandarin shoes is like walking on snow. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~ |]

"Picking pearls" is also a kind of traditional sports and was once popular in the northeast China. Participants are divided into two teams with six persons on each team. The ground is divided into four parallel quadrants: 1) water area, 2) limited area, 3) block area and 4) score area. One goal means a "pearl". In each group, there is a person playing the part of "fishing net". With a net in hand, he catches the ball (fishes peals) in the score area. Each team also has two history playing the part of the "clams". With clam-shaped wooden rackets in hand, they stand in front of the "fish net" of their opponents and try to block the ball cast towards the "fish net". The other three persons are the "pearl divers". They dash into the "water" (the intermediate range) to scramble for "pearls " against their opponents. When they get the ball, they try cast the "pearl" into the "fish net" of their own group and avoid having the ball intercepted by opponents. Each goal (picking a pearl) is scored with a ball thrown successfully into the net. Ten scores terminate an inning. Winners and losers are decided in three innings.

Pearls—"Nichuhe" in Manchu—are regarded as the symbol of brightness and happiness. It is said that the Manchu women ancestors once picked pearls in Mudan River and this sports came into being by imitating this kind of activity. The sports equipment is very simple. There are no strict requirements as to the size of the playing area. The game is still played in parts of northeast China with large concentrations of Manchus.

Like the Daur, Manchus are good field hockey players. The best players on the Chinese national team come from Gansu Province. They are mostly Manchu, who grew up in Inner Mongolia.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: 1) "Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China", edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company; 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China *\; 4) \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2022