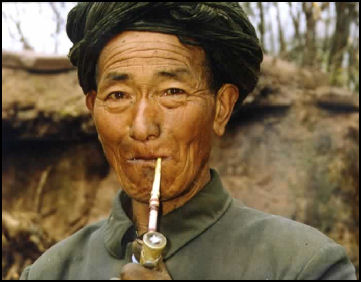

YI ETHNIC GROUP

The Yi are one the largest minority groups in China and the largest group on southwest China. They are uplands farmers and herders who live mostly in Sichuan and Yunnan provinces in the areas of the Greater and Lesser Liangshan mountain ranges at elevations of between 2000 meters and 3500 meters. They are particularly associated with the Hong River and Xiaoliang Mountains in Yunnan and the Daliang Mountains in Sichuan. Farming is the main occupation of the Yi. In some places Yi are engaged in raising animals. Main crops are corn, buckwheat, potato, wheat and rice. [Source: Lin Yueh-hwa (Lin Yaohua) and Naranbilik , “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

Also known as the Axi, Lolo, Loulou, Misaba, Nosu and Sani, the Yi are widely scattered and divided into many branches. They have called themselves by many different names such as "Nousu", "Nasu", "Niesu", "Axi" and "Sani". Some branches such as the Sani view themselves as distinct ethnic groups. After Communist China was founded in 1949, the various Yi groups were united under the name "Yi".

Yi (pronounced YEE) are the seventh largest ethnic group and the sixth largest minority in China. They numbered 9,830,327 in 2020 and made up 0.70 percent of the total population of China in 2020 according to the 2020 Chinese census. Yi populations in China in the past: 0.6538 percent of the total population; 8,714,393 in 2010 according to the 2010 Chinese census; 7,765,858 in 2000 according to the 2000 Chinese census; 6,572,173 in 1990 according to the 1990 Chinese census. A total of 3,254,269 Yi (0.56 percent of China’s population) were counted in 1953; 3,380,960 (0.49 percent of China’s population) were counted in 1964; and were 5,492,330 (0.54), in 1982. The total fertility rate for the Yi was 1.82 in 2010, compared with 1.14 for Han Chinese. About half of Yi live in Yunnan and a fifth live in Liangshin Li Autonomous Prefecture in Sichuan. Another 700,000 or so live in Guizhou. There are also significant numbers in Guangxi. [Sources: People’s Republic of China censuses, Wikipedia]

See Separate Articles: LOLO AND NUOSU (YI) IN THE IN THE 1900s factsanddetails.com; YI CULTURE AND LIFE See Separate Article factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Yi Dance video YouTube ; Book Chinese Minorities stanford.edu ; Chinese Government Law on Minorities china.org.cn ; Minority Rights minorityrights.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Ethnic China ethnic-china.com ;Wikipedia List of Ethnic Minorities in China Wikipedia ; Travel China Guide travelchinaguide.com ; China.org (government source) china.org.cn ; People’s Daily (government source) peopledaily.com.cn ; Paul Noll site: paulnoll.com ; Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science Museums of China Books: Ethnic Groups in China, Du Roufu and Vincent F. Yip, Science Press, Beijing, 1993; An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of China, Olson, James, Greenwood Press, Westport, 1998; “China's Minority Nationalities,” Great Wall Books, Beijing, 1984

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Everything Nuosu” by Susan Gary Walters Amazon.com; “Chinese Yi Ethnic By Zhong Shi Min Zhou Wen Lin Zhu Bian (1991) Amazon.com; “Minorities of Southwest China: An Introduction to the Yi (Lolo and Related Peoples and an Annotated Bibliography)” by Alain Y. Dessaint (1980) Amazon.com; “Perspectives on the Yi of Southwest China” by Stevan Harrell Amazon.com; Religion, Festivals and Language “Masters of Psalmody Bimo: Scriptural Shamanism in Southwestern China” by Aurélie Névot Amazon.com; “The Nuosu Book of Origins: A Creation Epic from Southwest China” by Mark Bender, Qingchun Luo, et al. Amazon.com;“The Saizhuang Festival of Yi Ethnic Group” by Li Song Amazon.com; “The Torch Festival of the Yi Ethnic Group by Yan Xiangjun and Liu Xiaoyu Amazon.com; “The Legend of the Torch Festival” Amazon.com; “Texts of Niesu, a Southeastern Dialect of Nuosu: Analyzed Spontaneous Narratives and Grammatical Notes” by Ding; Misi Rymga Hongdi Amazon.com; :A Grammar of Nuosu” by Matthias Gerner Amazon.com; Contemporary Issues “Research on the Ethnic Relationship and Ethnic Culture Changes West of the Tibetan–Yi Corridor” by Gao Zhiying Amazon.com; “Bridging Traditions and Technology: Empowering Chinese Ethnic Minority-Yi and Designer Brands in the Modern Age” by Trixie Tang Amazon.com;“Evaluation of an HIV peer education program among Yi minority youth” by Shan Qiao Amazon.com; “Doing Business in Rural China: Liangshan's New Ethnic Entrepreneurs’by Thomas Heberer Amazon.com ; Culture and Crafts: “Mountain Patterns: The Survival of the Nuosu Culture in China” by Bamo Qubumo, Stevan Harrell , et al. Amazon.com; “The Art of Silver Jewellery: From the Minorities of China, The Golden Triangle, Mongolia and Tibet” by René Van Der Star Amazon.com; “Encyclopedia of Chinese Traditional Furniture, Vol. 2: Ethnical Minorities” by Fuchang Zhang Amazon.com

Places Where the Yi Live

The Yi live mainly in Yunnan, Guizhou and Sichuan provinces and the northwestern part of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. Most Yis are scattered in mountain areas, some in frigid mountain areas at high altitudes, and a small number live on flat land or in valleys. The altitude differences of the Yi areas directly affect their climate and precipitation. Their striking differences have given rise to the old saying: "Different skies a few miles away" in the Yi area. This is the primary reason why the Yis in various areas are so different from one another in the ways they make a living. [Source: China.org |]

The places with the highest numbers of Yi are: 1) the Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture of Sichuan; 2) the Honghe Hani and Yi Autonomous Prefecture, The Chuxiong Yi Autonomous Prefecture, counties like Lunan, Nanjian, Eshan, Yanbi, Ninglang, Bijie and Liupanshui region in Guizhou; and 3) Longlin Autonomous County for different nationalities in Guangxi. 4) Most Yi live in Yunnan. Most counties and cities of Yunnan are settled by Yi people. The the most populated areas are Chuxiong Yi Autonomous Prefecture, Ailao Mountain and Wumeng Mountain areas in Honghe River Hani Yi Autonomous Prefecture, and Little Liangshan Mount area to the north of Dianxi. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences]

Honghe Hani and Yi Autonomous Prefecture in Yunnan near the border of Laos and Vietnam

1) There are maybe more than 1.5 million Yis in Sichuan Province, and most of them live in an area south of the Dadu River and along the Anning River. Traditionally, this area is subdivided into the Greater Liangshan Mountain area, which lies east of the Anning River and south of the Huangmao Dyke, and the Lesser Liangshan Mountain area, which covers the Jinsha River valley and the south bank of the Dadu River. There are over a million Yis in the Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture, which holds the single largest Yi community in China. 2) Yunnan Province probably has more than four million Yis, most of whom are concentrated in an area hemmed in by the Jinsha and Yuanjiang rivers, and the Ailao and Wuliang mountains. Huaping, Ninglang and Yongsheng in western Yunnan form what is known as the Yunnan Lesser Liangshan Mountain area. In Guizhou, more than half a million Yis live in compact communities in Anshun and Bijie. Several thousand Yis live in Longlin and Mubian counties in the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. |

According to the 2000 census, there were about 1.3 million Yi in the Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture in Sichuan and 3 million in Yunnan Province, mostly in Chuxiong Yi Autonomous Prefecture and in a number of autonomous counties and townships in both northern and southern Yunnan. At that time about 560,000 lived in Guizhou Province, and some 4,600 were located to east as the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. [Source: Ian Skoggard, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

The Yi areas in are rich in natural resources. The Jinsha (Upper Yangtze) River runs through Sichuan and Yunnan. It and its tributaries surge through Yi areas in northern and northeastern Yunnan are enormous sources of water power. The Yi areas are not only rich in coal and iron, but are also among China's major producers of non-ferrous metals. Gejiu, China's famous tin center, reared the first generation of Yi industrial workers. Various Yi areas in the Greater and Lesser Liangshan Mountains, western Guizhou, and eastern and southern Yunnan abound in dozens of mineral resources, including gold, silver, aluminum, manganese, antimony and zinc. Vast forests stretch across the Yi areas, where Yunnan pine, masson pine, dragon spruce, Chinese pine and other timber trees, lacquer, tea, camphor, kapok and other trees of economic value grow in great numbers. The forests teem with wild animals and plants as well as pilose antler, musk, bear gallbladders and medicinal herbs such as poris cocos and pseudoginseng. |

Origin of the Yi

The Yi have a long history. They share a common ancestry with the Bai, Naxi, Lahu and Lisu and appeared around present-day Kunming around the 2nd century B.C. The ancestors of the Yi were known as the Qiang, one of the groups in China that is different from but also gave birth to the current minority known as the Qiang that live near the Yi.

The ancient Qiang originally lived in the north and northwest of present-day China in what is now Shanxi, Gansu, and Qinghai and were primarily herders and nomads. Beginning around 4,000-5,000 years ago, a part of the Qiang population migrated in successive waves toward southwest China, mixed with the native peoples, and finally settled in Sichuan, Yunnan, Guizhou, and Guangxi. After settling, the Yi became farmers, a process that finished during the Western Han Dynasty (206 B.C-.A.D. 8). From this time onwards they were known as the Yi. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

The ancestors of Yi people, known as Kunming people, had close relations with the Shiqiang people. Historical records written in the Han and the old Yi languages show that the ancestors of the Yi, Bai, Naxi, Lahu and Lisu ethnic groups were closely related with ancient Di and Qiang people in west China. In the period between the 2nd century B.C. and the early Christian era, the activities of the ancient Yis centered around the areas of Dianchi in Yunnan and Qiongdou in Sichuan. After the 3rd century, the ancient Yis extended their activities from the Anning River valley, the Jinsha River, the Dianchi Lake and the Ailao Mountains to northeastern Yunnan, southern Yunnan, northwestern Guizhou and northwestern Guangxi. [Source: China.org |]

In the Eastern Han (25-220), Wei (220-265) and Jin (265-420) dynasties, inhabitants in these areas came to be known as "Yi," the character for which meant "barbarian." After the Jin Dynasty, the Yis of the clan named Cuan became rulers of the Dianchi area, northeastern Yunnan and the Honghe (Red) River area. Later those places were called "Cuan areas" which fell into the east and west parts. The inhabitants there belonged to tribes speaking the Yi language. |

See Origin of the Qiang and Qiang migrations Under QIANG MINORITY factsanddetails.com

Early History of the Yi

Yi concentrations in Sichuan and Yunnan

The Yi have traditionally occupied important trade routes used to carry tea and gems northward from Yunnan and Southeast Asia and horses and knives southward from northern China and Central Asia. They have had a lot of contact with groups in their region the Miao, Lisu, Hui, Hani, Dai and Zhuang — and the Han Chinese.

On the Nuoso Yi, Rev. C. E. Hicks of the United Methodist Mission, Zhaotung, Yunnan wrote in the the Chinese Recorder in March 1910; The Nuosu are not the original inhabitants of the Zhaotung district in Yunnan and the adjoining parts of Guizhou. According to their own tradition, they came from Tibet, and it is worthy of note, as confirmation of this, that some of the Nuosu race are to be found all the way from the borders of Tibet to Zhaotung. They say their ancestors were two brothers, Wu-sa and Wumeng, who, like Esau and Jacob, struggled together in the womb of their mother: hence say the Nuosu of the present time, the wildness of our hearts and our fondness for fighting. [Source: “Among the Tribes of South-west China” by Samuel R. Clarke (China Inland Mission, 1911)] .

Coming to the Zhaotung Plain, they found a people already in possession of the land, whom they called the P'u, and whom the Chinese to-day speak of as the Yao. This is the same name, and the Chinese use the same character for it as for the Yao about Nien Chow in Guangdong Province, mentioned in Chapter II. Possibly they are the same tribe. As we have already explained, the word Yao means “ dog “ or “ jackal.”This is a term that the Chinese would naturally apply to a people they regard as much inferior to themselves, and might apply it to very different races. It seems almost impossible now to discover who the Yaoren, who preceded the Nuosu around Zhaotung, really were. Chinese tradition in that district says they inhabited the plain many centuries ago, when it was covered with forests, and that their houses were like huge burrows in the hillsides. The Nuosu say the Yao moved to Sichuan, but the Chinese say they moved to Guangdong. It may be the Chinese say they moved to Guangdong because they know there are people now in that province known by that name. The only vestige of the Yao race now remaining are the mounds of earth which are conspicuous on the plain. Some of these mounds have been opened, and in them have been found rough unhewn stones and burnt bricks of an unusually large size, marked with a peculiar pattern. Both Chinese and Nuosu are agreed that the Yao were not Miao.

According to the Chinese government: “Legends and records written in the old Yi script show that the Yis went through a matriarchal age in ancient times. Annals of the Yis in the Southwest records that the Yi people in ancient times "only knew mothers and not fathers," and that "women ruled for six generations in a row." Patriarchy came into being at least 2,000 years ago. Roughly in the 2nd and 3rd centuries B.C., the Yis living around the Dianchi Lake in Yunnan entered class society. In the early Han Dynasty, prefectures were set up in this area, and the chief of the Yi people was granted the title "King of Dian" with a seal. [Source: China.org |]

In the Tang and Song dynasties, the Yis living in "East Cuan" were called "Wumans." In different historical periods, "Cuan" changed from the surname of a clan to the name of a place, and further to the name of a tribe. In the Yuan and Ming dynasties, "Cuan" was often used to refer to the Yis. After the Yuan Dynasty, part of "Cuan" acquired the name "Lolo" (Luoluo, Ngolok), which probably originated from "Luluman," one of the seven "Wuman" tribes in the Tang Dynasty. From that time on, most Yis called themselves "Lolo," although many different appellations existed. This name lasted from the Ming and Qing dynasties until the 1950s. |]

Yi During the Imperial Chinese Era

In the A.D. 8th century, the ancestor of the Yi and Bai ethnic groups founded the Kingdom of Nanzhao in Yunnan Province. "Nanzhao" was established in the northern Ailao Mountain and the Erhai areas, with the Yis as the main body and the Bai and Naxi nationalities included. The head of the state was granted the title "King of Yunnan." In the same period, "Luodian" and other states appeared in the Yi areas in Guizhou. In 937, the state of "Dali" superseded "Nanzhao,".[Source: China.org |]

In the 8th century, six principalities unified to create the powerful Nanzhao kingdom, whose capital was in Dali. It ruled Yunnan for 247 years and ten of its 13 kings were granted titles by the Tang Dynasty (618–907). The Nanzhao Kingdom was led by ancestors of the Yi and Bai ethnic groups. Chinese historians say the Nanzhao Kingdom was ruled by a Yi aristocratic elite, whose subjects were mostly Bai.

In the 13th century, "Dali" and "Luodian" were conquered by the Mongols. The Mongol-ruled Chinese Yuan Dynasty (960–1279) set up regional, prefectural and county governments and military and civil administrations in the Yi areas in Yunnan, Guizhou and Sichuan, appointing hereditary headmen to rule the local inhabitants under the tusi system. During the Imperial Chinese era certain ethnic minorities in southwest China and Southeast Asia were nominally ruled on behalf of the central Chinese government under the tusi system. Tusi, often translated as "headmen" or "chieftains", were hereditary tribal leaders recognized as imperial officials by the Yuan (960–1279), Ming (1271-1368), and Qing dynasties (1368-1644) of China. Tusi were located primarily in Yunnan, Guizhou, Tibet, Sichuan, Chongqing, the Xiangxi Prefecture of Hunan, and the Enshi Prefecture of Hubei. Tusi also existed in the historical dependencies of China in what is today northern Myanmar, Vietnam, Laos, and northern Thailand. [Source: Wikipedia]

According to the Chinese government: “By the end of the Yuan Dynasty, the feudal economy of the Yi landlords in Yunnan had developed rapidly, but remnants of the manorial economy and slavery still existed to varying extents in the secluded areas. The Ming Dynasty used both administrative officials from elsewhere and local hereditary headmen, and some of the governments consisted of both types of administrators, expanding the influence of the feudal landlord economy. The large number of Han immigrants also promoted economic growth in the Li areas.

Trade between Han and Yi consisted mainly of Yi exchanging medicinal materials, furs, and other local products for salt, cloth, and iron provided by Han merchants. The Yi were also heavily involved for a while in the opium trade. The Yi maintained their slave-owning system and resisted attempts by the imperial government to change in their social structure. It wasn’t until the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) that their kind aristocratic leaders were replaced by Manchu or Chinese officers appointed by the central government. This enhanced direct Chinese rule over the Yi areas, hastened the disintegration of the manorial economy and marked the decline of the slavery system but not its extermination. Slavery held on some areas until the 1950s. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

See Nanzhao and Dali Kingdoms Under MINORITIES IN SOUTHEAST ASIA AND SOUTH CHINA: factsanddetails.com

Yi Feudalism

Yin 1902

According to the Chinese government: “ Most of the Yis in Yunnan, Guizhou and Guangxi had entered feudal society earlier on, and a developed landlord economy had emerged in most areas except for remnants of the manorial economy in some areas of northeastern Yunnan and northwestern Guizhou. The Yi people who were under feudal rule, were mainly engaged in agriculture and animal husbandry. The growth of handicraft industries and commerce varied from place to place. Generally speaking, the production level of Yis living near cities and towns was approximate to that of local Hans, but was much lower in mountain areas. [Source: China.org |]

“Landlords accounted for 5 per cent of the population in those areas, and poor peasants and farmhands 60 to 80 per cent. The land possessed by landlords was on the average 10 times or several dozen times the amount owned by poor peasants, who were subjected to cruel feudal exploitation. Land rent paid in kind reached 60 to 70 per cent of the harvest and tenants had to bear heavy corvee (forced labor) and miscellaneous levies. Though the system of appointing hereditary headmen in northeastern Yunnan and northwestern Guizhou was abolished in the Qing Dynasty, some local landlords, , until 1949, used political power and influence in their hands to bully and exploit peasants as slave owners did, treating poor peasants as serfs. |

“Slavery kept production at an extremely low level for a long time in the Greater and Lesser Liangshan Mountain areas in Sichuan and Yunnan. While agriculture was the main line of production, land lay waste and production declined strikingly. Slash-and-burn cultivation was still practiced in some mountain areas. The lack of irrigation facilities and adequate manure, coupled with heavy soil erosion, lowered average grain output to less than a ton per hectare. Animal husbandry was a major sideline with sheep making up a large part of the livestock. The rate of propagation was very low due to extensive grazing and management. |

“For many centuries, barter was the form of trading among the Yis in the Liangshan Mountain areas. Goods for exchange mainly included livestock and grain. Salt, cloth, hardware, needles and threads and other daily necessities were available only in places where Yis and Hans lived together. Occasionally, some Han merchants, guaranteed safe-conduct by Yi headmen, carried goods into the Liangshan Mountain areas. At the risk of being captured and turned into slaves, they went and often made a net profit of more than 100 per cent. Suffering from a severe shortage of means of production and of subsistence, the Yis had to endure heavy exploitation in order to get a little essential goods. One hen was worth only a needle, and a sheepskin only a handful of salt. Many slaves had to go without salt all the year round.” |

Black Yi, White Yi and Yi Slavery

The Yi kept slaves until the late 1950s. There were two kinds of slaves — those that lived in the house and those that lived outside. Being an outside slave was preferable to being an inside one. Many of the slaves were captured Han Chinese.

According to the Chinese government: “Due to complex historical reasons, the slave system of the Yis in the Liangshan Mountains lasted till 1949. Before 1949, the Yis in the Liangshan Mountain areas were stratified into four different ranks — "Nuohuo," "Qunuo," "Ajia" and "Xiaxi." The demarcation between the masters and the slaves was insurmountable. The rank of "Nuohuo" was determined by blood lineage and remained permanent, the other ranks could never move up to the position of rulers. [Source: China.org |]

Yi in 1903

“"Nuohuo," meaning "black Yi," was the highest rank of society. Being the slave-owning class, Nuohuo made up 7 per cent of the total population. The black Yis controlled people of the other three ranks to varying degrees, and owned 60 to 70 per cent of the arable land and a large amount of other means of production. The black Yis were born aristocrats, claiming their blood to be "noble" and "pure," and forbidding marriages with people of the other three ranks. They despised physical labour, lived by exploiting the other ranks and ruled the slaves by force. |

“"Qunuo," meaning "white Yi," was the highest rank of the ruled and made up 50 per cent of the population. This rank was an appendage to the black Yis personally and, as subjects under the slave system, they enjoyed relative independence economically and could control "Ajia" and "Xiaxi" who were inferior to them. "Qunuo" lived within the areas governed by the black Yi slave owners, had no freedom of migration, nor could they leave the areas without the permission of their masters. They had no complete right of ownership when disposing of their own property, but were subjected to restrictions by their masters. They had to pay some fees to their masters when they wanted to sell their land. The property of a dead person who had no offspring went to his master. Though the black Yi slave owners could not kill, sell or buy Qunuo at will, they could transfer or present as a gift the power of control over Qunuo. They could even give away Qunuo as the compensation for persons they had killed and use Qunuo as stakes. So, Qunuo had no complete personality of their own, though they were not slaves. |

"Ajia" made up one third of the population, being rigidly bound to black Yi or Qunuo slaveowners, who could freely sell, buy and kill them. "Xiaxi" was the lowest rank, accounting for 10 per cent of the population. They had no property, personal rights or freedom, and were regarded as "talking tools." They lived in damp and dark corners in their masters' houses, and at night had to curl up with domestic animal to keep warm. Supervised by masters, Xiaxi did heavy housework and farm work all the year round. They wore rags and tattered sheepskins, and lived on wild roots and leftovers. Slave owners inflicted all sorts of torture on those who were rebellious, fettered them with iron chains and wooden shackles to prevent them from escaping. Like domestic animals, Xiaxi could be freely disposed of as chattels, ordered about, insulted, beaten up, bought and sold, or killed as sacrifices to gods. |

“Corvee was the basic form of exploitation by the slave owners. Qunuo and Ajia must use their own cattle and tools to cultivate their masters' land. Qunuo had to perform five, six or more than 10 days of corvee each year. They could send their slaves to do it or pay a sum of money instead. Corvee performed by Ajia took up one third to one half of their total working time. They often had to neglect their own land because of cultivating the land of their masters. Besides corvee, Qunuo and Ajia had to take usurious loans imposed by their black Yi masters. |

“Ordered about to toil like beasts of burden, the slaves had no interest in production at all. To win freedom, slaves in the Liangshan Mountain areas resorted to measures like going slow, destroying tools, maltreating animal, burning their masters' property and even committing suicidal attacks on their masters. Though it was hard for slaves in remote mountain areas to run away, they still tried to escape at the risk of their lives. Spontaneous and sporadic rebellions staged by slaves against slave owners never ceased. Organized and collective struggle for personal rights also grew, and collective anathema often turned into small armed insurgence.” |

Revolutionary Contributions of the Yi

The Yi once evoked fear over much of southwest China. In 1874, a Hui Muslim named Du Wenxiu united the Bai, Naxi, Yi and Dai in a rebellion against the Qing dynasty. The rebellion was brutally put down in 1892. Missionaries arrived when the Burma Road was constructed nearby in 1937-38. According to the Chinese government: “ The Yi people have a glorious tradition of revolutionary struggle. In the recent 100 years or more the Yis waged powerful anti-imperialist and anti-feudal struggles as well as those against slave owners. Influenced by the Taiping Revolution (1851-1864), the struggles waged by the Yis and other nationalities against the Qing government lasted more than a decade. [Source: China.org |]

“In 1935, the Chinese Red Army pushed north to resist the Japanese invaders. The troops on the historic Long March passed through the Yi areas, leaving a good and deep impression on the Yis wherever they went. On their way through northwestern Guizhou and northeastern Yunnan, the Red Army cracked down on local tyrants, wicked gentry and corrupt officials, and opened their barns to relieve the starving Yis. The Red Army distributed confiscated grain, salt, ham, clothes and other such goods among the Yis and people of other ethnic groups, who in return gave enthusiastic assistance to it. Many young Yis joined the Army. |

“In 1935, the Chinese Red Army pushed north to resist the Japanese invaders. The troops on the historic Long March passed through the Yi areas, leaving a good and deep impression on the Yis wherever they went. On their way through northwestern Guizhou and northeastern Yunnan, the Red Army cracked down on local tyrants, wicked gentry and corrupt officials, and opened their barns to relieve the starving Yis. The Red Army distributed confiscated grain, salt, ham, clothes and other such goods among the Yis and people of other ethnic groups, who in return gave enthusiastic assistance to it. Many young Yis joined the Army. |

“After crossing the Jinsha River, the Red Army pushed towards the Dadu River in two prongs from Yuexi and Mianning. Supported by the Army, the Yis and Hans in Mianning established the Worker-Peasant-Soldier Democratic Government of the county, formed revolutionary troops, abolished the "hostage system" imposed by the Kuomintang government, and set free several hundred Yi headmen and their relatives held as hostages. The Red Army strictly observed discipline, firmly implemented the Chinese Communist Party's policy for minority groups, declared that it aimed to emancipate the minority groups, and proclaimed that all poor Yis and Hans were kith and kin. It called on the Yi people to unite with the Red Army and overthrow the warlords and fight for national equality. Inspired by the Red Army's policies, Yuedan the Junior, the chieftain of a Yi clan in Mianning County, entered into alliance with the Red Army General Liu Bocheng. Helped by the Yis and the chieftain, the Red Army troops passed through the Yi areas without a hitch and won the victory of capturing the Luding Bridge and forcing the Dadu River.” |

Ending of Slavery and Development Under the Communist Chinese

When the Communist Chinese took over China in 1949, Han Chinese and other ethnic groups migrated into Yi areas. Many modern techniques of farming and stock raising were introduced. Over time, local industries and enterprises were developed and education, health and infrastructure were greatly improved. According to Chinese government: “The founding of the People's Republic of China ended the bitter history of enslavement and oppression of the Yis and people of other nationalities in China. From 1952 to 1980, the Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture of Sichuan, the Chuxiong Yi Autonomous Prefecture and the Honghe Hani and Yi Autonomous Prefecture of Yunnan were established one after another. Autonomous counties for the Yi or for several minority groups including Yi were founded in Eshan, Lunan, Ninglang, Weishan, Jiangcheng, Nanjian, Xundian, Xinping and Yuanjiang of Yunnan, Weining of Guizhou and Longlin of Guangxi. [Source: China.org |]

“In the spring of 1958, reforms concluded in the Yi areas in the Greater and Lesser Liangshan Mountains in Sichuan and Yunnan. The reforms destroyed slavery, abolished all privileges of the slave owners, confiscated or requisitioned land, cattle, farm tools, houses and grain from the slave owners, and distributed them among the slaves and other poor people. In the Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture and the Xichang Yi areas, 120,000 hectares of land were confiscated, and 280,00 head of cattle, 34,000 farm tools, houses composed of 880,000 rooms and 8,000 tons of grain were either requisitioned or purchased and given to the poor and needy along with 4,700,000 yuan paid as damages by unlawful slave owners. The reforms emancipated 690,000 slaves and other poor people, making them masters of the new society. The people's government also built houses and provided farm tools, grain, clothes, furniture and money for the slaves and other poor people and helped them build their own homes. In the Liangshan Mountains, the government set up homes for 1,400 old and feeble slaves who had lost the ability to work under slavery. Many former slaves got married and started their own families, and many families were reunited. |

“There was no industry at all in the Yi areas before 1949 except for the Gejiu Tin Mine in Yunnan and a few blacksmiths, masons and carpenters taken from the Han areas to the Liangshan Mountains. Now people in the Liangshan, Chuxiong and Honghe autonomous prefectures have built farm machinery, fertilizer and cement factories, small hydroelectric stations and copper, iron and coal mines. Lack of transportation facilities was one of the factors contributing to the seclusion of the Liangshan Mountains. Construction of roads started right soom after 1949. In 1952, the highway connecting Sichuan and western Yunnan was reconstructed and opened to traffic. At the same time, trunk highways linking the Liangshan Autonomous Prefecture with other parts of the country were constructed. The Yixi Highway was opened to traffic in 1957, linking up the Greater and Lesser Liangshan Mountains for the first time in history. A highway network extending in all directions within the prefecture had been formed by 1961. By the end of 1981, the total length of highways in the prefecture had increased from seven km. before 1949 to 7,368 km. While there were only 18 push carts in the whole area before 1949, the number of vehicles in 1981 reached 11,000, of which 5,000 were motor vehicles. |

“The local transportation department employed a total of 10,000 people. The Chengdu-Kunming Railway crosses six counties in the Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture over a distance of 337 km., with 45 stations on the line. With the development of the local economy, people in the prefecture had built 1,480 hydroelectric stations with a total generating capacity of 97,000 kw. By 1981, providing electric power and lighting for 80 per cent of the area. |

“The local transportation department employed a total of 10,000 people. The Chengdu-Kunming Railway crosses six counties in the Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture over a distance of 337 km., with 45 stations on the line. With the development of the local economy, people in the prefecture had built 1,480 hydroelectric stations with a total generating capacity of 97,000 kw. By 1981, providing electric power and lighting for 80 per cent of the area. |

The Yi people now have primary schools in all villages. The autonomous prefecture began setting up middle schools, secondary technical schools and schools for training ethnic teachers in the late 1950s. In 1981, there were 180 middle schools with 220 minority teachers and 12,000 students, 3,780 elementary schools with 3,700 minority teachers and 66,900 pupils. Children of emancipated slaves and poor peasants now have access to education. A new generation of Yi intellectuals with socialist consciousness is coming to the fore, and many Yi cadres hold leading positions at all levels of government in the prefecture. |

“In the past, there were no professional doctors, and the only way to avert and cure diseases was to pray. Now there are hospitals and clinics in all counties. Serious epidemic diseases such as smallpox, typhoid, leprosy, malaria, cholera have either been brought under control or wiped out by and large. A lot of traditional medical experience of the Yis has been collected, summed up and improved. The world famous Yunnan baiyao (a white medicinal powder with special efficacy for treating haemorrhage, wounds, bruises, etc.) is said to have been prepared according to a folk prescription handed down for generations by Yi people in Yunnan.” |

Yi Language

The Yi language belongs to the Yi language branch of the Tibetan-Burmese family in the Sino-Tibetan Family. It is divided into six dialects, five subdialects, and 25 regional idioms: The six dialects are: 1) the eastern dialect, 2) the western dialect, 3) the southern dialect, 4) the northern dialect, 5) the middle dialect and 6) the southeastern dialect. There is big difference among these dialects. To some there is no such thing as a Yi language. They are the six different dialects mentioned above are different languages. Their writing is similar, but not identical. Many Yis in Yunnan, Guizhou and Guangxi know standard Chinese (Mandarin). [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

The Yi have a very old, a syllabic script, developed in the 13th century or earlier. Many villages have a shaman or chief that keeps a scroll of pictograms that tell the story of where the Yi came from but otherwise few Yi know this written form The Chinese government helped them standardize their written language into Chinese characters. It is estimated that the extant old Yi syllabic script has about 10,000 words, of which 1,000 are words of everyday use. A number of works of history, literature and medicine as well as genealogies of the ruling families written in the old Yi script are still seen in most Yi areas. Many stone tablets and steles carved in the old Yi script remain intact. Since the old Yi language is not consistent in word form and pronunciation, it was reformed after 1949 for use in books and newspapers. [Source: China.org]

The Yi writing is a kind of ideographic, syllabic writing called chuan wen ("traditional script"), "Wei writing", "Lo writing", and "Lolo writing" in Chinese historical records. Yi script seems to have derived from Chinese characters. More than 2000 words are in common use. It is usually written from the left to the right. "The Southwestern Yi Records" is a famous book written in Yi characters. The earliest form of Chinese pinyin was used for the Yi written language with about 1,000 widely used characters. In 1957, a standard Yi language diagram, with 819 standard characters, was promoted. [Source: Chinatravel.com ~]

Yi Religion and Shaman (Bimo)

The have traditionally honored a pantheon of spirits and gods — including ones representing animals, plants, the sun, the moon and the stars — and incorporated elements of Buddhism and Taoism into their spiritual belief system. Sacrifices were made to ancestors and ghosts to placate them. According to the Yi creation myth: “In the beginning there was only women.” Protestant and Catholic missionaries had some success converted the Yi in the early 20th century and some of these communities remain alive today.

The Yi believe that everything that moves or grows has its own spirit. They worship the Buddha of Peace and Tranquillity (Taiping), considered the God of Grain, three times a year. What is called the "Heavenly Buddha" is simply a braid on the forehead of a man. The braid, about 20 centimeters (8 inches) long and three centimeters (1.5 inches) around,. It is wrapped tightly in a piece of cloth. The Yi believe this braid is the lord of fortune and misfortune, so sacred and inviolable that anybody who touches it will be looked upon as an enemy. The Yi have traditionally fought intensely to protect his braid. In some districts, the Yi worship Asailazi, the god who created the ideographic script of the Yi. There is also a cult to the God of Wind. It is believed that things left behind by the deceased possess their own spirits and the power to protect the people. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

The Yi have traditionally performed ceremonies for marriage, the beginning and end of feuds and initiations. Sacrifices were offered to the ancestors of the lineage and household and to other spirits. There were common ceremonies that were held as the need arose and special sacrifices that took place on dates fixed by the Yi calendar occasions. The Yi had a well-developed knowledge of astronomy. [Source: Lin Yueh-hwa (Lin Yaohua) and Naranbilik, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

Yi shaman are known as bimo. Highly respected, they carry out sacrifices and perform healing rituals with incense and bowls of chicken blood. Headmen are responsible for controlling ghosts with magic. Often bimo were the only ones who could read the sacred texts that included clan histories, myths and literature.The chicken is an important totemic animal to the Yi. It is honored in a special dance performed at night by dozens of people wearing hats with strung beads arranged in the shape of chicken combs. To the accompaniment of a moon guitars, the dancers execute fast tempo steps from the knee down that mimic the movements of a chicken.

The religious rites are also performed by sorcerers called Suye. They and bimo bang on sheepskin drums, recite scriptures, offer sacrifices, and perform sacred dances while in a state of trance to expel the ghosts and malevolent spirits. According to the U.S. Department of State: “Adherents of the Bimo shamanistic religion, practiced by many of the eight million ethnic Yi living in southwest China, continued to seek government approval to register Bimo as an officially sanctioned religion, but were unable to do so. This limited the Yi people’s ability to preserve their religious heritage. [Source: “International Religious Freedom Report for 2013 China”, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor,U.S. Department of State]

Yi Funeral and Wake

The dead are believed by the Yi to travel to another world where they can continue their lives. Special care is taken to placate the dead to make sure they don’t become malevolent ghosts. The Yis in the Greater and Lesser Liangshan Mountains in Sichuan practiced cremation, burning dead bodies in mountains and burying the ashes in the ground or placing them in caves. After the funeral, the mourners used bamboo strips wrapped with white wool to make memorial tablets, which were wound with red thread and placed in the trough carved in a wooden stick. Again, the stick was wrapped with white cloth or linen. Some memorial tablets were made of bamboo or wood and carved in the shape of figurines, which were placed at the young sons' homes. Three years later, such memorial tablets were either burned or placed in secluded mountain caves. [Source: China.org |]

Festival clothes

Funeral rites include "calling back the spirit of the dead." C. Le Blanc wroteL A wooden cross is made, half a foot in length, with wool on the top, plant leaves on the sides, and some grass at the bottom. It is the symbol of the spirit. The shaman recites the scripture and the family offers a sacrifice. For underground burial, a man will dress up like a ghost and lead the way before the coffin while beating a drum. The shaman also walks before the coffin. After the burial, the family should prepare a "mourning plate," which is hung on a wall in the home. The plate, according to ritual prescriptions, should be "sent off " two or more years later. In accordance with the position of the dead, a send-off team consisting of five to seven persons is arranged. They take the mourning plate down from the wall, place it in front of the house, kill livestock for sacrificial offerings, put the plate on a family member's back, then follow the shaman to send it off. They put the mourning plate in the cavern of their ancestors. Moreover, a ceremony is performed to save the souls of the dead. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

On a wake she attended, Rachel Beitarie wrote in China Digital Times: "In one village, just about two kilometers into the mountains, several young women put on heavy silver jewelry. They are getting ready for a wake of sorts visiting the house of an old relative who has just passed away. The procession goes through muddy fields, with older women helping the girls with their big silver head-dresses and complicated hair-styles. Many young children tag along or are carried on mother backs, but no man is to be seen.” The men are all busy in the backyard of the deceased since morning. They slaughtered many cows as offerings to the departed spirit and are now smoking the meat that will later be offered to everyone. Young women here speak even less Chinese than the older ones, and are hesitant to speak to an outsider at all, though they are happy to have their pictures taken and are encouraged to do so by the men obviously proud of their women elaborate costumes. Young men, on the other hand, are chatty to the point of being flirtatious, with the confidence of well-traveled people: Many have gone to work in places as far away as Shenzhen and Dongguan, only coming back home for the summer traditional festivals. After paying respects to the departed and having feasted on the rare meat dish, most women and children go back home, leaving the men alone for a long session of Baijiu drinking, outside on the street in the rain.

Yi Calendar

The Yi have their own calendar — comprised of ten 36-day months — with a year that is divided into two halves, each ending with a solstice. The Yi celebrate two new years — one in the summer and one in the winter. An additional five days are tacked on to each year for festivals. The Yi calendar is believed to be the oldest continually used calender in the world. It was developed around 1500 B.C. by an astronomer named Shidi Tianzi according to observations made of seasons and the sun with a vertical pole called a gnomon. The months and the days were named after animals like the barking deer, blue sheep and leopard. By the A.D. 5th century the calendar was widely used across China and remained widely used in southern China until fairly recently.

The earliest Yi calendar divided the year into 10 months, each with 36 days. The tenth month was the period of the annual festival. Influenced by the Han Lunar Calendar, the Yis later divided the year into 12 months, using the 12 animals representing the 12 Earthly Branches to calculate the year, month and date. There was a leap year every two years in the Yi calendar. The New Year festival was not fixed but generally fell between the 11th and 12th lunar months. [Source: China.org]

Yi Festivals

The main Yi festivals are the Spring Festival, the Yi New Year Festival, he Torch Festival, New Rice Festival, Flower Inserting Festival, Bullfight Festival and Dress Competition Festival. As the Yi inhabit areas where there are many Han Chinese, they participate in Han Chinese festivities such as the Chinese Spring Festival (Chinese New Year). The Yi are scattered over a wide area and they are divided into many branches, so their festival culture is very varied and colorful. There are festivals that revolve around agriculture, social intercourse, entertainment, commemorations, celebrations and religious sacrificial offerings. The Torch Festival and Yi New Year are the grandest and celebrated by the largest number of Yi. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

The main Yi festivals are the Spring Festival, the Yi New Year Festival, he Torch Festival, New Rice Festival, Flower Inserting Festival, Bullfight Festival and Dress Competition Festival. As the Yi inhabit areas where there are many Han Chinese, they participate in Han Chinese festivities such as the Chinese Spring Festival (Chinese New Year). The Yi are scattered over a wide area and they are divided into many branches, so their festival culture is very varied and colorful. There are festivals that revolve around agriculture, social intercourse, entertainment, commemorations, celebrations and religious sacrificial offerings. The Torch Festival and Yi New Year are the grandest and celebrated by the largest number of Yi. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

Spring Festival is celebrated on the first day of the first lunar month (between January 21 and February 20 on the Western calendar). Families kill pigs and sheep, prepare special meals and visit each other. The first thing a family does is carry two buckets of water on a shoulder pole. Family members use it for cooking or washing, but not for laundry. They go to the countryside for picnicking, singing, dancing, wrestling, and horse racing.

Yi New Year is not fixed. It is usually held in the 10th or 11th lunar month (between October 24 and January 18 on the Western calendar) but is decided through divination by the shaman. The Yi New Year, also called "Winter Month New Year" and "the Tenth Month New Year", has traditionally been the most important traditional festival for Yi people. The Yi calendar only has ten months in a year and the New Year is usually celebrated during the tenth lunar month, or eleventh lunar month when there is one, and lasts three to five days. The specific time is different for different places. During the festival, people stop working and every household butchers pig or sheep as an offering to ancestors and then happily feast on it and to celebrate the coming of a new year together with family members and relatives. ~

In celebrating the New Year, the Yis would slanghter cattle, sheep and pigs to offer sacrifices to ancestors. In the old days in Liangshan Mountains, people of the subordinate ranks had to present half a pig's head to their masters to confirm their affiliation. The Yis in Yunnan and Guizhou now celebrate the spring festival as the Hans do. |

The Guanyin Fair is a traditional festival celebrated on the 5th to 20th day of the 3rd lunar month in late March or April at Taoist temples all over China that honors Guanyin (the Goddess of Mercy). The festival is a particularly big event in the Yunnan Province, where the Bai, Yi and Naxi people commemorate the arrival of Guanyin on Mount Cangshan and her victory of over the evil King Luocha. This fair attracts people from all over Yunnan. The Bai, Yi and Naxi people dress up in their beautiful ethnic costumes.

The Winter New Year Festival (Kushi) is held around December 25th and the Summer New Year Festival (Zhair) is held in late July or early August. The latter features singing, dancing, harvest rites performances with musical instruments, ox fighting, wrestling contests, archery, and processions with torches lit from a central bonfire.

Yi Torch Festival

The Torch Festival is celebrated on the 24th or 25th day of 6th lunar month (between July 22 and August 20 on the Western calendar) in southwest China by the Bai, Naxi and Yi people. Participants light torches in front of their houses and set 35-foot-high torches — made from pine and cypress timbers stuffed with smaller branches — in their village squares. The Bulang, Wa, Lisu, Lahu, Hani and Jinuo minorities hold similar festivals but on different dates.

The Torch Festival is popular in all Yi areas. Courtship rituals, music, dancing around huge bonfires, bloodless bullfights, sheep fighting, wrestling, arrow-shooting, dancing, singing, swinging, horse racing, and tug-of-war are accompanied by heavy drinking. In the daytime, a ceremony is held to offer prayers to the gods or spirits associated with their lives. Prayers to earth God are made with chicken blood. After sunset, people light torches to send the gods backs. One Yi told Smithsonian magazine, “The celebration is all bustle and excitement. We slaughter goats and chickens, drink liquor, sing songs and dance, We also invite our best friends to a big feast.”

During the Torch festival, Yis in all villages carry torches and walk around their houses and fields, and plant pine torches on field ridges in the hope of driving away insect pests. After making their rounds, the Yi villagers gather around bonfires, playing moon guitars (a four-stringed plucked instrument with a moon-shaped sound box) and mouth organs, dancing and drinking wine through the night to pray for a good harvest. The Yis in some places stage horse races, bull fighting, playing on the swing, archery and wrestling. \=/

The Yi Torch Festival is held at different times among different Yi groups. It is generally held on about 24th of the sixth lunar month in Sichuan and Yunnan, and about the 6th of the sixth lunar month in the Guizhou Yi region. The length of the celebration varies from three to seven days. When it comes, some people butcher chicken and pig, and some butcher cattle and sheep as sacrifices offered to the ruler of heaven, the mother of earth and ancestors. The Yi also pray for the safety of humans and domestic animals and for an abundant harvest of all food crops. At nightfall, torches are lit and villages compete to have the best torch. Recreational, sports and entertaining activities include antiphonal singing (alternate singing by two choirs or singers), dancing, bullfight, horse race, wrestling, archery, and tug-of-wars. Business and trade activities are carried out. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, ~]

Because Yi people believe that torches get rid of evil and ghosts, they light up every corner of their house after the torch is lit. In some villages, torch teams go from house to house, and then gather at the edge of a village, or on slope or in fields to play torch games and hold a fire party, where young men and women decked out in their finest festival dress sing and dance and party all night long. An ancient poem describing proceeding centuries ago goes: "The mountain seems wrapped by rosy cloud; Uneven torches move back and forth with people which are like ten thousand of lotus flowers blossoming in mirage, and stars all over the sky fall down to the human world." ~

The Torch Festival honors a woman who leaped into a fire rather make love with a king. Before the village torch is lit people gather around it and drink rice wine. The village elders use a ladder to climb to the top of the torch as they distribute fruit and food to the villagers while they boisterously sing the "Torch Festival Song." The torch is then solemnly lit. The villagers light their torches off the village torch and sing and dance and eventually make their ways to their homes and light the torches there.

Origin of the Yi Torch Festival

There are records about the origin of the Torch Festival in the "Kunming County Annals" written in the Guangxu period of the Qing Dynasty: "There was a Yi woman Anan in the Han Dynasty. Her husband was killed by evildoers, and she swore that she would not submit to the killers. So she jumped into fire and died at that day (the 24th in the sixth lunar month). People felt very sad and held the festival for her. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

A description of another origin story from a different source goes: “King Piluoge of the Yunnanzhao (a local regime in ancient China) planned to meet of the rulers other five cities in the Songming Building. He wanted to trap and burn them to death so that he could swallow up their territory. The wife of King Dengdan—a woman named Cishan—tried to persuade her husband not to go, but he refused. Then she put an iron bracelet around the arm of her husband. He went as scheduled and was burned death. Cishan identified and brought back her husband's body according to the iron bracelet. Piluoge heard of her virtue and wanted to draw her over to his side, but Cishan closed the city gate and committed suicide. So people of Dian (an ancient name for Yunnan) burned torches to grieve over her." ~

In a folk legend, it is said that the Torch Festival stems from a time when God sent pests to destroy crops in the human world and Yi people drove them away with fire. Some people also say that the festival commemorate a fight in which ancestors defeated the Prince of the Devils by attacking them with fire. Most of the records and legends are forced interpretation. Chinese historians say the Torch Festival for praying for good harvests and came into being as a result of the poor harvests by the ancient Yi society. Over the years the religious elements of the festival have diminished and the entertainment value has increased. ~

Image Sources: VPO Yi website; Nolls China website; Johompas; Darmouth College, Wiki Commons

Text Sources: 1) “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China”, edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company; 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China *\; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, Wikipedia, BBCand various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2022