DERUNG MINORITY

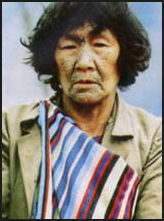

Derung facial tattoos

The Derung are one of the smallest minorities. They mostly live a valley surrounded by 5,000-meter-high mountains in northwestern Yunnan near the Myanmar border and speak a Sino-Tibetan language with no written form and practice animism. In the old days some extended families lived in large communal longhouses. The Derung are very isolated and have relatively few contacts with outsiders. The Chinese government has tried to get the Derung to forsake their traditional ways. In some cases they have simply moved deep into the mountains to get beyond government control. [Source: Norma Diamond, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

The Derung are among the poorest peoples in China. They practice slash and burn agriculture and hunt and collect wild foods in the forest. Both men and women wear squares of distinctive striped flax cloth that is used a cloak, skirt or wrap around during the day and a blanket at night. In the old days women wore facial tattoos that indicated which clan they belonged to. The Derung are also known as Dulong, Drung, Derong, Trung, and Qiu. They call themselves "Derung" and "Dima", and were known in different historical periods as the "Qiao", "Qiu", "Qiu Ren", "Qiu Zi", "Luo", "Qu Luo". In 1952, their formal name was decided as "Derung" by the Chinese government.

The Derung language belongs to the Zang and Mian language branch of Sino-Tibetan family of languages. It is similar to the Nu language in Gongshan area. There are two Derung dialects: the Dulong River dialect and Nu River dialect. There are some linguistic and cultural differences between the people who speak these dialects. Maybe there are two different ethnic groups included under the common denomination of Derung. [Source: Ethnic China]

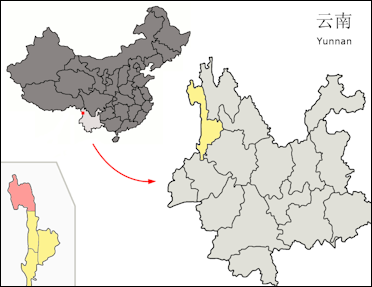

The Derung people mainly live in a difficult-to-reach area of northwest of Yunnan Province in 1) Nujiang Lisu and Nu Autonomous Prefecture in western Gongshan Nu and Derung Autonomous County on the banks of the Dulong River (upper Irrawaddy River) and 2) along the Nu River in Qile Village in the Weixi Autonomous County of the Lisu Minority Group. 3) Some also live in Chawaluo of Chayu County in Tibet. 4) On top of this a small number of Derung live in Myanmar. The area where the Derung is isolated and mountainous, with dense forests, abundant rains but soil with low fertility. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences]

The Dulong River valley extends 150 kilometers from north to south. It is flanked on the east by Mt. Gaoligong, 5,000 meters above sea level, and on the west by Mt. Dandanglika, 4,000 meters above sea level. The area has abundant rainfall due to the influence of monsoon winds from the Indian Ocean; the annual precipitation is 2,500 mm. Virgin forests cover the mountain slopes, and medicinal herbs, wild animals and mineral deposits abound. Crops grown in the area used to be limited to maize, buckwheat and beans, but since the mid-20th century rice and potatoes have been introduced. [Source: China.org]

The Derung are the fifth smallest minority out 55 in China. They numbered 6,930 in 2010 and made up 0.0005 percent of the total population of China in 2010 according to the 2010 Chinese census. Derung population in China: 7,431 in 2000 according to the 2000 Chinese census; 5,816 in 1990 according to the 1990 Chinese census. In 1982 they were only 4,250-4,600. [Sources: People’s Republic of China censuses, Wikipedia]

See Separate Article DERUNG (DULONG, DRUNG) RELIGION, CUSTOMS AND TATTOOS factsanddetails.com ; THREE PARALLEL RIVERS AREA OF YUNNAN factsanddetails.com; NU MINORITY factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS AND MUSIC: Folk Songs of the Bai, Nu & Derung Peoples (Album) Amazon.com; “China's New Socialist Countryside: Modernity Arrives in the Nu River Valley” by Russell Harwood Amazon.com; “Life Among the Minority Nationalities of Northwest Yunnan” (1989) by Che Shen , Xiaoya Lu, et al Amazon.com; “Highlights of Minority Nationalities in Yunnan” (1969) Amazon.com ; “The Yunnan Ethnic Groups and Their Cultures” by Yunnan University International Exchange Series Amazon.com; “Tibetan Borderlands” by P Christiaan Klieger Amazon.com; “Yunnan–Burma–Bengal Corridor Geographies” by Dan Smyer Yü and Karin Dean Amazon.com; “Frontier Tibet: Patterns of Change in the Sino-Tibetan Borderlands” by Stéphane Gros, Willem van Schendel, et al. Amazon.com; “On the Margins of Tibet: Cultural Survival on the Sino-Tibetan Frontier”by Ashild Kolas and Monika P. Thowsen Amazon.com; “Mapping Shangrila: Contested Landscapes in the Sino-Tibetan Borderlands’ by Emily T. Yeh, Christopher R. Coggins, et al. Amazon.com

History of the Derung

Where the Derung live in Yunnan

Little is known about the history of the Derung in part because they have lived in very isolated area of Yunnan Province as along as anyone has ever known. Even today the Derung Valley is closed to external communication during half of the year. There is scarce information about them in the imperial histories and travelers' chronicles refer to them in passing, and usually through secondary sources. Some scholars have argued that because their language belongs to the Tibeto-Burmese family, they probably came from the northwest of China, migrating southward through Sichuan to Yunnan provinces as did other ethnic groups in their linguistic group did. According to their tradition, and transportation routes in the area suggest they arrived in the valley of the Dulong River from Lanping and Jianchuan counties and believed to be the first inhabitants of the region they occupy. [Source: Ethnic China *]

The Derung are believed to have been living in the Dulong River (upper Irrawaddy River) Valley from at least the time of the establishment of the Nanzhao Kingdom, near present day Dali, in the 8th century. According to historical records, during the Tang (618-907 AD) and Song (960-1279AD) Dynasties, the major settlement of the Derungs was under the jurisdiction of the Nanzhao and Dali principalities. From Yuan (1279-1363AD) Dynasty to Qing (1644-1911AD) Dynasty, the Derungs were ruled by the Chinese imperial court-appointed Tusi Mu (a Yi ruler) from Lijiang and paid imperial tribute to the Tusi of Lijiang, under whose jurisdiction they were officially living. During the middle period of Qing Dynasty, their settlement was put under the administration of the Naxi headmen of Kangpu and Yezhi and then solely governed by the Yezhi headman. [Source: Chinatravel.com]

The Derung’s life changed two hundred years ago, when their isolation was broken by the arrival of two powerful neighbors, the Tibetans from the north and the Lisu from the east. Both imposed themselves on the Derung, causing significant modifications to their society. The Lisu carried out sporadic expeditions in Derung territory to capture Derung for slaves. The Derung sought aid and protection from the Tibetans, exchanging slaves (orphans or people separated from Derung society) for cows. *\

In 1909, a full-time Qiuguan (governor) was appointed to take charge of the Dulong river valley. In 1918, the government established Changputong Prefectural Administrative Office in Gongshan County, which was transformed into Establishment and Administration Bureau of Gongshan County. It introduced the Bao and Jia household registration system of old China to the Derung area. \=/

Toward the end of the 19th century some French missionaries arrived among the Derung. In the 1930s, American and Canadian missionaries arrived there. Christian churches were built in four Derung villages. Some Derung were open to the teachings of the Protestant missionaries in the area, and in the mid-1950s it was estimated that close to one-third of the Derung identified themselves as Christian.

Many Derung had no contact with the outside world until the arrival of the communist government after the establishment of the Peoples Republic of China in 1949. The socialist reforms of the fifties didn't have much impact on the Derung but some aspects of Derung culture, such as the face tattooing of the Derung women and the sacrifice of cows, were considered primitive by the Chinese and all but eliminated. *\

Until the mid the 20th century, the Derung still a very undeveloped life based on limited agriculture, hunting and food gathering. Their clothes with primitive coverings made of knitted flax, leaves and hides. The Derung’s relationships with the outside has increased significantly in recent decades. Many young Derung have received education in the regional centers and even in the provincial capital, Kunming. The first major road to their region opened at the end of 1999 (before, it was necessary to walk three days from Gongshan) and this has further reduced their isolation. However many Derung still live in a very undeveloped state, relying on slash-and-burn agriculture, collecting and hunting for most of their food and income. *\

Derung Written Language of Gaps and Knots

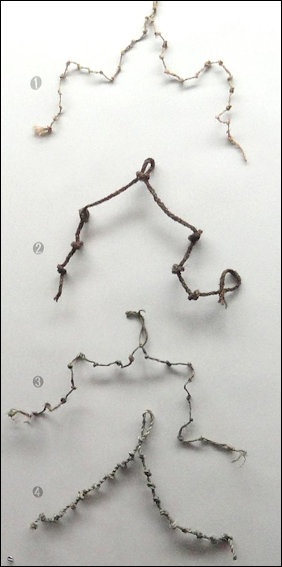

knot communications used in Yunnan

The Derung have traditionally not had a written language. Instead they recorded things and exchanged information by tying knots and carving wood. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences ~]

In carving method, wooden boards of various kinds, with different signs, were used as ordinary letters and books, and to record and convey the landlord's orders, common people's debts, gift lists. Carved boards with landlord messages were large and resembled a wooden swords, about 20 centimeters wide and 70 to 80 centimeters long, with thinner edges, a slanting point and a handle at the bottom. Boards with different contents contain different gaps, lines and graphics. For instance, on the board conveying the landlord's tax demands, there is a big gap on the top left edge and several small gaps at the bottom, which means a chief supervisor will come, with several attendants, while a big and two small gaps on the right side means that a headman will come and two villagers should go to greet him. ~

The boards used by ordinary folk are smaller, and used to record things like debts and gift items. If, for example, a family has no ox to offer as a sacrifice and they want to borrow one from their relatives or friends, they measure the circumference of the animal’s chest with a piece of thin bamboo, then measure the length of the bamboo with their fists to see how many fists long the piece is, and lastly to carve the number of fists respectively on the edges of a board. The board is cut in two so each side has one. When the ox is returned, the same procedure of measuring is carried out. The difference is made up with grain. After the debt is paid the two boards are put into the fire, finalizing the transaction. ~

The Derung have also traditionally counted time with knots. Knots are made on a thin flax rope, with one knot representing one day. When going out, one knot is tied every day, and on the way home, one knot is untied every day. In this way, time and the journeys are accurately calculated. The New Year is the happiest day for Derung people. But since there is no fixed date for the festival, every year people have to set the date beforehand, which is also done using knots. If it is agreed that the New Year is in 10 days, many ropes with 10 knots are made and sent to friends and relatives. One knot is untied each day, and after the last one is untied, the festival comes. ~

Traditional Derung Society

According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “ In the late 1940s and 1950s the Derung were still organized into fifteen exogamous patrilineal clans (nile ), each of which held claim to particular valley lands, mountain lands, and forest areas. The clans were divided into ke'eng, or villages, composed of several closely related multigeneration households of twenty to thirty persons each. There were village communal lands and lands assigned to houses. Each personal name incorporated three names: the name of the clan, house, or village; one's same-sex parent's name; and an individual given name. Nowadays, a person must also have a proper Chinese name for registration purposes. At puberty, girls received facial tattoos that indicated their clan affiliation, a custom no longer followed.. [Source: Norma Diamond, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

According to the Chinese government: “Before the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Derung society maintained many vestiges of the primitive commune system. There were 15 patriarchal clans called "nile." Each nile consisted of several family communes, and each commune occupied a separate territory marked off by boundaries such as streams and mountain ridges. The clan was further divided into "ke'eng," or villages, where people dwelt in common long houses. [Source: China.org]|]

“Agricultural production remained at a very low level until 1949, due mainly to the primitive nature of the Derungs' farm tools. Every year saw several lean months when their diet had to be supplemented by food gathering, hunting and fishing. The ke'eng members pursued collective farming on common land and held their hunting, fishing and gathering grounds in common. However, in modern times this system was slowly giving way to ownership of the means of production by blood-related families. Following financial difficulties due to illness or debt as a result of the imposition of taxes, land sales gradually led to the emergence of oppressive landlords. And rich households used to make seasonal workers and destitute children work for them. The Derungs produced some primitive handicrafts, including bamboo and rattan articles and engaged in the weaving of linen. But the absence of both traders and towns made barter the only form of exchange. |

“Agricultural production remained at a very low level until 1949, due mainly to the primitive nature of the Derungs' farm tools. Every year saw several lean months when their diet had to be supplemented by food gathering, hunting and fishing. The ke'eng members pursued collective farming on common land and held their hunting, fishing and gathering grounds in common. However, in modern times this system was slowly giving way to ownership of the means of production by blood-related families. Following financial difficulties due to illness or debt as a result of the imposition of taxes, land sales gradually led to the emergence of oppressive landlords. And rich households used to make seasonal workers and destitute children work for them. The Derungs produced some primitive handicrafts, including bamboo and rattan articles and engaged in the weaving of linen. But the absence of both traders and towns made barter the only form of exchange. |

“The ke'eng was the grassroots organization of Derung society. Its members regarded themselves as being descended from the same ancestor. A Derung's personal name was preceded by that of the family and his father's name. In the case of a woman, her mother's name was included. Each ke'eng was headed by a "kashan" whose duties were both administrative and ceremonial. He also directed warfare and mediated disputes. The ke'engs were politically separate entities, which formed temporary alliances in times of great danger threatening from outside communities. Marriage within the clan was forbidden and monogamy was the rule in recent times, but vestiges of primitive group marriage remained, such as several sisters marrying one man. Polygamy was also not unknown.” |

Derung Life, Honesty and Security

The Derung raise corn and buckwheat as their staple foods. They love watery wine, roasted meat, tea and tobacco. Their dress is plain and simple. They used to wrap their bodies with one or two pieces of flax cloth, as clothes in the daytime and quilts at night. Women used to tattoo their face. Now the tattooing is largely a thing of the past and most Derung wear normal Western-style or Chinese style clothes. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

The Derung people live a simple and honest life. They would never think of picking up something left by others on the road and claiming them as theirs. There is no need to lock or even close their doors at night. When they find things on the road, they wait there for the owner or try to find the owner, to give the things back. When traveling far away, the Derung divide their carried food into many portions, and put some in trees or caves, to eat on the way back. The passersby, no matter how hungry, would take this food without permission. Even, items like clothes can be put anywhere on the road, with a stone on top, showing the owner puts it there intentionally. No one would touch them.

Derung live in wooden or bamboo houses. Their barns are mostly built behind the house, or even on a hill or near a field, a some distance from the house. Even though there valuable tools and animals are kept in the barn, there is only a bamboo or wood stick on the door. People are never worried about thieves. Even if they leave their house for a long time they don’t lock it without worries. A break-in, in the Derung mind, would never happen. Other Derung traditional village virtues include respecting elders, caring for children, warmly helping the poor and being polite and hospitable. When one family is in trouble or needs help the whole village pitches in to assist them.

Derung Houses and Bridges

Derung residence include wooden houses and pile dwellings of bamboo split. Mainly in the area north of Kongmu, wooden houses are built log-cabin-style by intersecting and overlapping timbers fixed by sawing the wallboards or logs into the the four corners. The area south of Kongmu mainly has pile dwellings of bamboo split. Dozens of piles are inserted into the earth of of a slope. To build one of these" landing on thousands of feet" houses, people first build a structure with timbers, enclose the walls and cover the floor with bamboo split, then fasten them tight with bamboo ropes and vines, and finally cover the roof with couch grass.[Source: Chinatravel.com]

The traditional ke'eng long house — made of logs in the northern areas and of bamboo further south — is made up of a large, oblong room which serves as the ke'eng's common quarters, with two rows of smaller rooms at the back. Each small room has a fireplace in the middle and is the home of an individual family. At one time, each ke'eng had a common granary, but this was replaced by granaries owned by small groups of families.[Source: China.org]

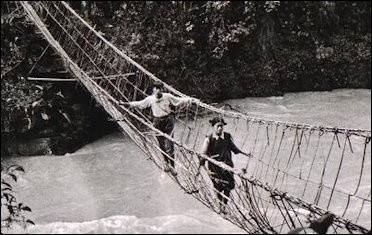

bridge over the Dulong River

Erecting bridges made of thin bamboo strips and vines is a great event in the lives of the Derungs. Whenever they complete a bridge, they dress in their best clothes, bang a gong and beat the drum and sing and dance in celebration. To make this vine-net bridge: 1) people weave two ropes with vines and bamboo exclusively found in the Dulong River valley, 2) tie them in parallel to stout trunk or fixed piles on the sides of the river, 3) then weave nets with wild vines or bamboo splits gathered from mountains and hang them on the vine ropes on both sides and 4) finally lay boards wider than foot soles or several poles put together at the bottom of the nets for people to walk on. When one sets foot on the bridge, the movement of the feet can cause the bridge to shake, sway and rock. It is often not so easy for non-natives to cross such bridge, which sometimes are at great heights over rushing rapids. However, the Derung people are able to manage it even when carrying weights on their backs.

Derung Food

The Derung staples are fried noodles made of highland barley, corn, rice or millet. They also like baked potatoes, cakes and biscuits as well as porridge. They grind root tubers of all kinds of wild plants and use the starch to make cakes and biscuits or porridge. Side dishes are made from planted beans and melons as well as from gathered bamboo shoots, bamboo leaves and various kinds of fungi. They usually cook them with peppers, wild garlic and table salt in the wok. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

The Derung bake fish over a blazing fire or slow fire and then eat it them with seasoning while drinking. Bee pupae are popular exotic food of the Derung nationality. Some attribute their rapid population increase over the past hundred years to eating bee pupae regularly. Among the typical Derung foods are potatoes with Hema (a kind of poisonous hemp), chicken braised with strong white spirit, Jimi (stinky bamboo shoots) and baked blue sheep large intestines and braised Jimi and Hema cooked on a flagstone.\=/

The Derung way of cooking has changed from using stones to using woks. Now they often cook food by boiling and baking. They have a preference for spicy and crisp food and love drinking. The most characteristic food is flagstone buns, which are made by pouring thing dough on very hot flagstone. The area around Qinglatong in the town of Bingzhongluo, Gongshan County is famous for producing a kind of flagstone, which doesn’t burn in a fire and isn’t split by water. When you put the flagstone on the tripod of the fireplace and bake buns on it without adding oil, the buns don’t stick to the stone and come out fragrant and delicious. \=/

Derung Development

Derung sacrifice

The Derung traditionally practiced slash-and-burn agriculture, fishing, forest and mountain hunting, and collecting of wild plants for food and medicinal use. Since the 1950s, the Chinese government government has encouraged them to plant of paddy rice and raise cattle and pigs. Norma Diamond wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: ““In 1956, the Derung-Nu Autonomous County was established, and authorities encouraged the Derung to participate in a land-reform program. (Chinese sources disagree about the extent to which this plan was carried out and how.) Shortly thereafter, the government organized the Derung into collectives and communes, which did not replicate former clan or lineage holdings but instead created new units in which Derung of various clans joined members of other ethnic groups to work assigned areas of land. This plan was facilitated by government irrigation projects that opened up some 6,000 hectares for paddy rice in the Dulong River valley. However, recent reports (see Shen Che) suggest that many Derung can be found in the uplands, practicing their traditional economy. Even so, the institution of the extended-family communal longhouse is disappearing, rejected by the younger generation. [Source: Norma Diamond, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

According to the Chinese government: The year 1956 saw the establishment of the Gongshan Derung and Nu Autonomous County, with a Derung as the county magistrate. The first task for the government was to provide the Derungs with clothing and farm tools, and promote farm production and education. In light of the conditions in Derung society, the government decided that land reform would be inappropriate, and concentrated on the development of production. Beginning in 1954, about 6,000 hectares of arable land was brought under cultivation in the Dulong River valley. Irrigation projects transformed part of the land into paddy fields, which had been non-existent up until then. A few years later, the area began to sell surplus grain to the state. Along with the increased farm production went a boost for livestock raising (cattle, goats and pigs), the cultivation of medicinal herbs and the processing of animal hides. [Source: China.org |]

“Primary schools, unknown in the Derung area in the past, numbered over 20 in the 1980s. Clinics and health stations have put the shamans out of business. Special attention has been paid to making the mountainous Derung area accessible to the outside world. Some 150 km of roads have been constructed, and ferries and bridges now span the roaring torrents of the hill streams. Modern commodities are now available to the Derungs. There is also a post office, bookstore and film-projection team in the valley. Several small hydroelectric power stations, built in the last couple of decades, have brought electricity to the Derung villages. |

New Road and Tunnels Opens Up Derung Areas

Reporting from the Derung areas in the Dulong River Valley,Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times: The narrow valley is one of the most remote and pristine in China. Monkeys, Asian black bears and the rare goatlike takin roam through rain-soaked forests above a river the color of jade. In spring, hillsides are splashed with pink rhododendron blossoms. Until 2014, snowfall on a mountain pass blocked vehicle access for many months each year. The lifeline of this northwest corner of Yunnan Province is the Dulong River, which begins on the Tibetan plateau and flows through this valley into Myanmar, where it merges into the Irrawaddy. In Yunnan, the river runs 90 kilometers, or 56 miles.[Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, April 24, 2016]

Now, in this sliver of land on the eastern rim of the Himalayas, the government is building new roads, expanding telecommunications and encouraging commercial ventures to alleviate poverty. Li Yingchun, who used to hike five days over a snowcapped mountain range from a village here to attend a boarding school, said a new paved road that runs through a seven-kilometer tunnel slicing into the mountains had made life easier. But he worries about the impact on both the environment and society from the explosion of activity.

Opened in 2014, the serpentine road has sheer drops, dizzying turns and rubble from rockslides. It has also cut travel time to the county seat — now a mere three hours rather than a full day’s rough drive along a 15-year-old dirt road, which was impassable in winter. Already, a state-owned enterprise has built at least two hydropower stations along the Dulong River. Hotels are springing up.

The Gaoligong mountain range has kept the Dulong valley secluded, separating it from the wider valley of the Nu River, where a mosaic of ethnic groups live. The ramparts of the Gaoligong challenged World War II pilots who flew over the Hump, transporting military goods from Indian bases used by the United States and its allies to Chinese forces battling the Japanese. Planes crashed in the region — the remnants of one are in a museum to the south.

The valley is still quiet, except for occasional bursts of construction. One paved road runs north from Dulong Town toward the Tibetan border, ending near Mr. Li’s hometown. Another goes to the border with Myanmar and no farther. In the last village is a red church; some Dulong are Christians, though most are animists. There is no frontier checkpoint. Along a dirt trail into Myanmar, the border is demarcated by nothing more than a small stone. With no paved roads leading out of the nearby villages in Myanmar’s Kachin State, ethnic Dulong there walk into this valley to sell herbs and vegetables.

Impact of New Road and Tunnel on the Derung

Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times: The changes that have transformed so many parts of China are unfolding at warp speed in the Dulong River Valley. It is home to almost all of the country’s 7,000 ethnic Derung.” High “peaks no longer cut off this valley, where the Dulong have lived for centuries in hillside villages. It is not just the new road and tunnel that now connect residents here to the outside world. China Mobile has set up 4G cellular data service across much of the valley, and is not shy about advertising this on billboards. One sign on the approach from the mountains to the main administrative village, Kongdang, says, “Take a photo of the beautiful scenery, transmit it to the world.” By the words are images of the jade river and of a local woman with intricate indigo tattoos on her face, once a common sight here.[Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, April 24, 2016]

“The buildings in Kongdang are concrete blocks, and many were built or renovated a few years ago. They are painted orange and have a silhouette of a horned cow’s head, a Dulong totem. A cow statue sits at the town entrance. The changes have been tremendous,” said Yang Yi, an ethnic Han man living in the Nu Valley who has been driving a passenger minivan between the two valleys for a decade. Transportation, clothes, daily life — it has all been transformed,” he said. “If you came here a decade ago, you would recognize the Dulong from their colorful clothes. Around three to five years ago, they began wearing modern clothes.” Even President Xi Jinping noted the changes. In January 2015, Mr. Xi met with seven representatives of the Dulong in Kunming, the provincial capital, and spoke of “getting rid of poverty” and “building a moderately well-off society,” according to an official news report.

“On a slope behind” a new “hotel is the old village. The few remaining residents there sit in wooden homes with fire pits, sometimes drinking homemade corn whiskey. The hotel occupies half the new village. The village homes and hotel villas were all designed and built together around 2012. Living here is much better than where we were before,” Kong Mingqing, 21, said as he stood by the porch of his new family home behind the hotel. Few ethnic Dulong have lived outside the valley, but Mr. Kong is an exception. He left to study vehicle maintenance in Hunan Province, he said, but returned in 2013 because of financial problems. “When I came back, it had already been transformed,” he said. “I don’t think too much about the changes coming. Of course, there will be changes.”

“Has the poverty alleviation plan succeeded?” he asked. “We’ve raised the awareness of the Dulong people here — how to communicate with outsiders, how to make money, how to live a better life.” But Mr. Yang also said he had heard that a couple of women in Pukawang had committed suicide a few years ago by drinking pesticide. He has a theory: “This was a primitive society,” he said. “Now the leap is happening too fast. Some of them cannot adapt.”

Tourism in the Derung Areas

Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times: It is tourism that provincial and county officials want to sell to the outside world. Word of the valley’s beauty is trickling out, and international agencies have recognized the Gaoligong Mountains National Nature Reserve as a crucial biosphere. The new road has made visiting easier, even if the nearest airport is a long day’s drive away. One recent afternoon, three ethnic Han backpackers from central China sat in the last village by the Myanmar border. People from outside the valley, many from other Yunnan towns, have come to work in restaurants and other service businesses that are counting on a tourist boom. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, April 24, 2016]

In the village of Pukawang, just south of the government town, a group of tourists from Shanghai drove up to a boutique riverside hotel, Green Cottage, opened in October by a Beijing entrepreneur — a poverty alleviation project supported by local officials. Officials gave families in Pukawang two new homes, one to live in and one to rent to the hotel company for use as guest villas. To each family, the hotel pays 5,000 renminbi per year, under $800. The hotel charges guests $25 to $75 per night for each of the 13 villas.

In Pukawang, the hotel has tried to employ villagers — part of the official plan to help raise local incomes — but has found that hard to do, said a manager, Yang Yubiao, an ethnic Bai from the Dali area. The villagers said they were tired of the work,” he said. “They left after two to three days.” Three of the hotel’s nine employees are ethnic Dulong from elsewhere in the valley, and the rest are outsiders, Mr. Yang said.

Image Sources: Nolls China website, People's Daily, Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: 1) "Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China", edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company; 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China *\; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2022