YI SOCIETY

Yi society has traditionally been divided into three classes; 1) nobles (the Black Yi); 2) commoners (the White Yi) and 3) slaves. The members of each class engaged in similar agricultural and herding duties. The Black Yi owned more land than the other groups and they rented out land mainly in return for military service. The lower classes generally did not perform work for the Black Yi. Sexual relations between members of different classes was a serious taboo and crime. [Source: Lin Yueh-hwa (Lin Yaohua) and Naranbilik , “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

Patrilineal descent defines kin groups which in turn form the basis of village and community organization. Most villages are made up of members of clan or a group clans that can trace their relationship back to a common ancestor. Villages have traditionally been competitive with one another and violent conflicts between them occurred. Territories and hunting grounds have traditionally been clearly demarcated and trespassing was a serious offense. In the old days, blood feuds were not uncommon. Conflicts over slaves, land. marriage and sex also occurred.

Clans and villages are led by headmen, usually senior members of the group, known for being glib and eloquent. Disputes and important issues were addressed in meetings of headmen. Social control was exerted through customary law and moral pressures. Violators of social norms, particularly those that involved sexual relations between members of different classes, were given harsh punishments.

See Separate Article YI MINORITY: HISTORY, RELIGION AND FESTIVALS factsanddetails.com ; LOLO AND NUOSU (YI) IN THE IN THE 1900s factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Everything Nuosu” by Susan Gary Walters Amazon.com; “Chinese Yi Ethnic By Zhong Shi Min Zhou Wen Lin Zhu Bian (1991) Amazon.com; “Minorities of Southwest China: An Introduction to the Yi (Lolo and Related Peoples and an Annotated Bibliography)” by Alain Y. Dessaint (1980) Amazon.com; “Perspectives on the Yi of Southwest China” by Stevan Harrell Amazon.com; Religion, Festivals and Language “Masters of Psalmody Bimo: Scriptural Shamanism in Southwestern China” by Aurélie Névot Amazon.com; “The Nuosu Book of Origins: A Creation Epic from Southwest China” by Mark Bender, Qingchun Luo, et al. Amazon.com;“The Saizhuang Festival of Yi Ethnic Group” by Li Song Amazon.com; “The Torch Festival of the Yi Ethnic Group by Yan Xiangjun and Liu Xiaoyu Amazon.com; “The Legend of the Torch Festival” Amazon.com; “Texts of Niesu, a Southeastern Dialect of Nuosu: Analyzed Spontaneous Narratives and Grammatical Notes” by Ding; Misi Rymga Hongdi Amazon.com; :A Grammar of Nuosu” by Matthias Gerner Amazon.com; Contemporary Issues “Research on the Ethnic Relationship and Ethnic Culture Changes West of the Tibetan–Yi Corridor” by Gao Zhiying Amazon.com; “Bridging Traditions and Technology: Empowering Chinese Ethnic Minority-Yi and Designer Brands in the Modern Age” by Trixie Tang Amazon.com;“Evaluation of an HIV peer education program among Yi minority youth” by Shan Qiao Amazon.com; “Doing Business in Rural China: Liangshan's New Ethnic Entrepreneurs’by Thomas Heberer Amazon.com ; Culture and Crafts: “Mountain Patterns: The Survival of the Nuosu Culture in China” by Bamo Qubumo, Stevan Harrell , et al. Amazon.com; “The Art of Silver Jewellery: From the Minorities of China, The Golden Triangle, Mongolia and Tibet” by René Van Der Star Amazon.com; “Encyclopedia of Chinese Traditional Furniture, Vol. 2: Ethnical Minorities” by Fuchang Zhang Amazon.com

Yi Life and Customs

The Yi have traditionally lived in small mountain hamlets with about 10 or 20 households, residing in single-story houses built of wood and earth with a double-sloped roofs held in place with stones. The houses generally have few furnishings. People sleep on the floor near a central fire pit with three stones. Animals are penned at night at one end of the house. In recent decades, many Yi have moved into Han-style brick-and-tile housing with livestock in adjacent but separate buildings

Men have traditionally done the heavy agricultural work such as plowing, making crafts and hunting. Women have traditionally done the agricultural field work, household chores and cloth making. There are a lot taboos regarding a women’s place in the group. Women are expected to stay home with the kids and do farm work. Work that requires exposure to the public is men’s work. Old women often fill their morning with chores and play cards with their friends in the afternoon. The AIDS and HIV rates are high among the Yi. Heroin use is also high, particularly those who live in towns like Ergu and Butao on the Kunming to Chengdu drug smuggling routes.

According to the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”: The Yi are known for their hospitality. Refusing a toast offered by the host is looked upon as most impolite behavior. The Yi pay much attention to courtesy shown older generations, not on the basis of age, but of seniority in the family or clan. ++“When receiving guests, the host will prepare a special meal of oxen, pig, sheep, or chicken, according to the position and familiarity of the guests. Before the meal, the host will present the animal or poultry to the guests, to show that it is live and healthy. After being killed, the animal or poultry will be cooked entirely, including the head, the tail, and the internal organs. These will all be shown after cooking, one by one, to the guests. The meal is very copious, the host inviting the guests to eat and drink without reserve. The host usually asks the guests to take home the head or upper arm of the animal. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Illiteracy has traditionally been high among the Yi, especially among women. Although primary schooling is, by law, compulsory and free of charge, many students in rural areas drop out each year. Relatively few go on to middle school. In the past, the Yi dealt with disease through both ritual and the use of local herbal medicines. If someone died of illness, a bimo was invited to make medicines for the dead. Medical care has been greatly improved since the Communist Chinese took over 1949. Modern medicine is available at varying degrees in Yi areas. [Source: Ian Skoggard, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

See Children in Sichuan Descend Down an 800-Meter Cliff to Get to School Under PROBLEMS AT CHINESE SCHOOLS: CHEATING, EXPLOSIONS AND MYOPIA factsanddetails.com

Yi Clans and Naming System

Tiger man Since ancient times, the Yi have practiced a joint naming system in which father's and son's names are linked. The last one or two syllables of the father's name should be put in front of the son's name. This system traditionally appeared at the transition period from matrilineal clan system to patrilineal clan system. It used to be popular or is still popular among Yi, Hani, Drung, Wa, Jingpo, Nus, Miao, Uyghur and Kazakh. The name system of the Yi, the father's name is ahead of the son's name. The last one or two syllables of the father's name are added before the son's name, and the last one or two syllables are added before the grandson's name. Thus their names are all linked with one another generation after generation. People can recite ancestors and pedigrees to tens of or even one hundred of generations, such as Apu Juma-Juma Denglun-Denglun Wuwu-Wuwu Gengzi-Gengzi Gengyan-Gengyan Ayi-Ayi Aqu-Aqu Libu. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

The name system of the Yi is not only a kind of naming method, it also closely associated with the clan system. It forms an oral family tree and records clan ties and pedigree in a way that is easy to recall and remember. It also make clear blood ties so property can be handed down according to patrilineal descent. In the past, every Yi family paid much attention to its family tree, and men were required to memorize it and recite it clearly. ~

The clan system is a traditional way in which the Yi organized themselves socially, politically and economically. In the Liangshan Yi region, for example, before the foundation of Communist China in 1949, a clan was a patrilineal blood group composed of clans, branches and single families. Every clan had a family tree passed on for generations, with the names linked between father and son, and named after a common male ancestor or a place name. Every clan had a common and fixed gathering place, and a common forest, pasture, hills and marshland. All members of the clan had an obligation to assist one another and to take out revenge for clan member wronged or injured. Every clan had a number of headmen that made decisions on clan affairs. of the clan. Intermarriage with the clan was prohibited. Because other political organization didn't exist in Liangshan Yi society, the clan becomes the basic social organization of the Yi society and functions as a local political organization to some extent. Some clans became stronger than others and hierarchy clan system came into being, with the Black Yi clans occupy a dominant position, and the White Yi clans being subordinate. ~

Before the Communists took over clan played a central role in Yi society and still remains important today. A Liangshan Yi saying goes: "Fish rely on water; Bees rely on mountain rock; Monkeys rely on the forest; People rely on clan." "Cattle and sheep are indispensable; Grain is indispensable; Clan is indispensable." From 1956 to 1958, the democratic reform movement was carried out in Liangshan region, and the slave-like system of the Black Yi and White Yi was eliminated and the clan system was abolished along with it. But even today, the Yi are well aware of which clan they belong to and what their obligations are. ~

Clans and Vestiges of Black Yi Slavery

According to the Beijing government: “Rigid rules were stipulated for marriages within the same rank but outside the same clan among the black Yis, who relied on the "mystery" of blood lineage as a spiritual pillar. Some 70,000 black Yis in the Liangshan Mountains formed nearly 100 clans, big or small, of which there were less than 10 big clans each with a male population of more than 1,000. Each clan's territory was clearly demarcated by mountain ridges or rivers, and no trespass was tolerated. There were no regular administrative bodies in the clans, but each had some headmen called "Suyi" (seniors in charge of public affairs) and "Degu" (seniors gifted with a silver tongue), who were representatives of the black Yi slave owners in exercising class dictatorship. They upheld the interests of the black Yis as a rank, were experienced and knowledgeable about customary law and capable of shooting trouble. "Degu," in particular, enjoyed high prestige inside and outside their clans. Headmen did not enjoy privileges over and above ordinary clansmen, nor were their positions hereditary. Important issues in the clans, such as settling blood feud and suppressing rebellious slaves, must be discussed at the "Jierjitie" (consultation among the headmen) or "Mengge" (general conference of the clan membership). [Source: China.org |]

“While preserving some of their original characteristics, the clans under the slave system mainly functioned as institutions to enforce rank enslavement and exploitation, splitting and cracking down on slave rebellions internally and plundering other clans or resisting their pillage externally. When subordinate ranks staged a rebellion, the black Yi clans would take collective action against it, or several clans would join hands to suppress it. Under such circumstances, the unanimity of interests among the black Yi slave owners fully manifested itself. Strictly controlled by the black Yi clans, the slaves could hardly run away from the areas administered by the clans. On the other hand, black Yis often fought among themselves in order to obtain more slaves, land or property. It follows that the clan, as an institution, was a force safeguarding and supporting the privileges of the black Yi slave owning class. |

“While preserving some of their original characteristics, the clans under the slave system mainly functioned as institutions to enforce rank enslavement and exploitation, splitting and cracking down on slave rebellions internally and plundering other clans or resisting their pillage externally. When subordinate ranks staged a rebellion, the black Yi clans would take collective action against it, or several clans would join hands to suppress it. Under such circumstances, the unanimity of interests among the black Yi slave owners fully manifested itself. Strictly controlled by the black Yi clans, the slaves could hardly run away from the areas administered by the clans. On the other hand, black Yis often fought among themselves in order to obtain more slaves, land or property. It follows that the clan, as an institution, was a force safeguarding and supporting the privileges of the black Yi slave owning class. |

“The white Yi clans, among the Qunuos and part of the Ajias, while being similar to the black Yi clans in form, were actually subordinate to various black Yi clans. Only a few white Yi clans were not subject to black Yi rule and they formed what was known as the independent white Yi area. The white Yi clans succeeded to some extent in protecting their own members, and at times they would unite in "legitimate" struggles to defend their own interests and win temporary concessions from black Yi slave owners. But, under the rule of the black Yi clans, they became an auxiliary tool of the slave owners to oppress the slaves. Some clan chieftains of the Qunuo rank were fostered by slave owners as proxies, called "Jiemoke" in the Yi language, who collected rents, dunned for repayment of debts and served as hatchet men, mouthpieces and lackeys for slave owners. | “There was no written law for the Yis in the Liangshan Mountains, but there was an unwritten customary law which was almost the same in various places. Apart from certain remnants of the customary law of clan society, this customary law reflected the characteristics of morality and the social rank system. It explicitly upheld the rank privileges and ruling position of the black Yis, claiming that the rule of slave owners was a "perfectly justified principle." The legal viewpoint of the customary law was clear-cut. Any personal attacks against black Yis, encroachment on their private property, violation of the marriage system of the rank and infringement on the privileges of the black Yis were regarded as "crimes," and the offenders would be severely punished.” |

Yi Marriage, Courting and Weddings

The Yi are generally monogamous. Marriages are usually between partners of the same rank from different patrilineage. Cross-cousin marriages between one person and the offspring of the father's sister or mothers' brother are preferred. Marriages were generally arranged by parents, Polygyny sometimes occurred. In these cases, each wife and her children had a household of their own, with the husband rotating visits between them. In the past members of some Yi groups were married at puberty, or as early age of four to five years. Some were even betrothed as infants [Source: Lin Yueh-hwa (Lin Yaohua) and Naranbilik, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Young male and female Yi are permitted to enjoy a "golden period of life" in which premarital sex is allowed and even encouraged. Young people engage in recreational group activities, such as singing and dancing and attend fairs and festivals to meet partners and develop courtship relations. The eighth of the second lunar month (between March 1 and 30 on the Western calendar) is a special festival for young people. One of the rituals is for boys to stick an azalea flower in the hair of the girl's they like. A couple typically gets engaged in their early teens and then enjoy conjugal visits. Only years later do they get married and set up house. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

C. Le Blanc wrote in the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life: “There are two favorite pastimes for the young people, namely Ganhuachang (Rushing to the flower place) and Paohuashan (Running around the flower mountain). Ganhuachang is actually a form of dating. As soon as a young fellow knows that a girl is now visiting a certain family, he arrives there at once and sings a tune accompanied by his traditional full moon-shaped mandolin outside the door. If the girl agrees to go dating, he will invite her to sing and dance at the flower place (a place for outdoor activities). Even married persons might add to the fun on occasion, especially when the dating couple becomes more serious. Paohuashan is a group activity organized by the village. Each household invites a guest from outside their village. The young men and girls line up and move round the mountains. They sing as they walk along. Whenever they arrive on a hilltop, they dance. When they return to the village in the evening, they meet the old folks waiting at the gate. Singing in antiphonal style with the old folks, they are allowed to enter the village only after they have won the singing contest.” [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

Grooms have traditionally been required to pay a bride price. Newlywed brides often remain at their parents house until their first child is born and then they move in with their husbands. Ceremonial bride kidnaping is practiced among some groups. In these, the bride is carried away on horseback by members of the groom’s family. Usually the groom's family sent people to the bride's home at a prearranged time.The bride was expected to cry for help, with her family half-heartedly giving chase. |~|

In another ritual, the groom’s family is at the receiving end of a mock attack when they try to snatch the bride. After a short “fight,” the bride’s family invites the groom’s family for a big feast. According to the Chinese government “People from the groom's side went to fetch the bride, her people would first "attack" them with water, cudgels and stove ashes, then treat them to wine and meat after a frolic scuffle, and finally let them take the bride away on horseback. On the wedding night, there would also be frolic fighting between the bride and the groom as part of the ceremony. These were obviously legacies of primitive marriage conventions. [Source: China.org]

Yi Families

The Yi generally live in nuclear families. Patriarchal and monogamous families were the basic units of the clans in the Liangshan Mountains. When a young man got married, he built his own family by receiving part of his parents' property. Young sons who lived with their parents could get a larger portion of the property. In the old days, there were rigid differences between sons by the wife and those by concubines in sharing legacies. Property handed down from the ancestors usually went to sons by the wife. [Source: China.org |]

The Yis traditionally associated the father's name with the son's (See Yi Clans and Naming System above). When a boy was named, the last one or two syllables of his father's name would be added to his own. Such a practice made it possible to trace the family tree back for many generations. In the Yi families, women were in a subordinate position with no right to inherit property, but the remnants of matriarchal society could still be seen clearly sometimes. The mother's brother has traditionally had a high position in Yi families and relations between such uncles and nephews were close. Slaves' marriages and homemaking were in the hands of slaveholders. The fate of slave girls was even more wretched, and they were forced to marry just to meet the needs of slaveowners for more slaves.

Both sons and daughters could inherit, although women generally received less than men.Youngest sons are expected to live with the parents and take care of them in old age. In return they inherit the family’s property. In the past there were rigid differences between sons by a wife and those by a concubine: Property handed down from the ancestors usually went only to the wives. Among the Black Yi, if a man died without issue his property would be received by his full brothers and his widow would be married to one of his kinsmen. Women received part of their inheritance as dowry at marriage, and dowry goods might include livestock and, in the case of the Black Yi, slaves.

Yi children are treated well. After the birth of a girl, her parents would a red thread around her head and change it with a new one frequently. This was a symbol of purity and happiness until the girl got married. Upper class boys have traditionally been trained in horsemanship and using weapons. In the past, customary laws and moral standards were o taught at an early age, and youngsters were expected to learn their clan genealogies by heart. For Black Yi this meant knowing some twenty generations or more. Even today, White Yi know the details of their ancestry for seven or eight generations.

Girls between the ages of 15 and 17 go through a “change skirt” coming-of-age ceremony in which they receive long, colorful skirts and earrings and have their hair style changed from a single plait to a double plait, signifying they are ready to married. Village elders divine a lucky day for the event. A black kerchief, lace, a new skirt, multicolored beads, and silver collar plate are prepared beforehand for the initiated girls. During the rite, males had to leave the house, while women and girls tease the initiated and expressed their good wishes. Only after the girl is combed and dressed in new kerchief skirt are males allowed to come back in the house and then they are expected to complement her beauty and maturity.

Yi and the One-Child Policy

Rachel Beitarie, wrote in China Digital Times: “In the Liangshan prefecture of south Sichuan, the mountains are high and the emperor is far away; therefore, the children are many. Most families here have four or five kids a woman says in very broken Mandarin. She herself has three so far, all under the age of five. Her friend, sitting on the paved concrete path next to her, has four. The friend, like many women, doesn’t speak a word of Chinese. They are both members of the Yi, or Nusuo. In this county, Butuo, they are over 90 percent of the population, and make for a very picturesque spectacle with their traditional colorful clothes on the backdrop of green hills and swift streams. It is a picture-perfect rural life, if one can ignore the poverty. Or the dirt.”[Source: Rachel Beitarie, China Digital Times]

“La-lo confirms that many women in the villages can’t speak or read Chinese. They are often pulled out of school to help in the fields or to take care of younger siblings, she explains. Officially, most minority groups are allowed to have two or sometimes three children, but the Yi are very traditional. Family planning rules are widely ignored and children are considered a blessing, even when dressed in rags or with faces and bodies so dirty that most suffer from skin rashes; it has to be said, though, that despite all that, small children here look quite happy, even when their only toy is an old basketball gone flat.”

La-lo only has two children and seems to be somehow negotiating their passage into China middle-class. Her older daughter works hard on her English homework and prefers to go by the English name Susan...I have always been curious La-lo laughs when asked how come her lot is different from that of other women. My mom encouraged me to study and go out to see other places that she never saw. I try to do the same with my daughter. It is good for a girl to study.

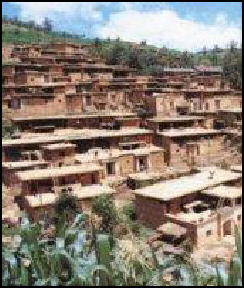

Yi Houses

Yi village

Yi people mostly live in mountainous regions. Their villages are generally located on slopes of gentle hills. Their villages are not big, often composed of no more a few dozen households. In the past, Yi aristocrats lived in imposing dwellings and spacious courtyards, even with watch-towers. Most Yi houses traditionally were low mud-and-wood structures without windows, which were dark and damp. The main bedroom was usually on the left. The room on the right was for livestock and stored item, usually with a loft for the children or for storage of grain. The central room served many functions. Furniture and utensils were usually made of wood. Sleeping areas were on the ground, behind the fire pit. In recent years Han-style brick-and-tile housing with livestock kept in adjacent buildings has become the norm.

There are different kinds of traditional Yi houses: Chacha houses (made of tree branches), shacks, wooden Luoluo houses, Waban houses (covered with board tile) and the Tuzhang houses (built with mud and wood which has flat roof). Some Yi live in two-storey buildings with the first floor for living and the second floor for storing grain, tools and other articles. Some household units consist of several buildings, constructed around a closed courtyard, with "three principal rooms and two side rooms". The principal rooms are tall and big while the side rooms are low and small. The first floor of the principal building has a living room for the parents and a place for entertaining guests. In the side rooms on both sides are the kitchen and children's rooms. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

The Yi board tile house is popular mainly in the Liangshan Yi region. The walls are built with soil or woven bamboo. Boards on the roof are covered with tiles and stones are put on them. The house is divided into three parts: the"Haku" (inner room), principal room and "Gaba" (outer room). A Yi saying goes: "People (outsiders) are not allowed to enter the Haku, and to touch the waist pocket." The inner room is living room and place to store valuables, which is why outsiders can not enter it. There is a fire pit in the principal room. This is the room for eating, drinking and entertaining guests. A fire is kept burning in the pit all year round, and this fire is used for cooking and keeping warm. People are not allowed to step on it or stride over it. The outer room is a place for storing things such as living and producing tools, water vats and stone mills. ~

The Tuzhang house is popular mainly in the mid-southern region of Yunnan. It is a flat roof house built with soil and wood at the foot of a hill. To build it: 1) wooden poles are erected as a frame; 2) walls of rammed by earth, slab stones or adobe are erected around the frame on all four sides of the house. 3) Crossbeams and purlin (roof parts) are put up on the posts. 4) Board or branches or placed on the purlin. 5) Bamboo or pine leaves are paved over this, and then a layer of mud is spread on them. 6) Then earth mixed with 1 percent lime is pounded to a thickness of 10 centimeters while being sprayed with water and put on the roof. 7) Slab stones, which are two to three centimeters thick, are laid as eaves around the roof. The house is strong and durable and is warm in winter and cool in summer. It resists fires and thus is called the "fire banking house". The flat roof is a good place for drying crops and relaxing in the summer. ~

In the old days, according to the Chinese government: “Ordinary Yi houses had double-leveled roofs covered with small wooden planks on which stones were laid. Interior decoration was simple and crude, with little furniture and very few utensils, except for a fireplace consisting of three stones. In the Liangshan Mountains, slave owners' houses and slaves' dwellings formed a sharp contrast. Slaves lived with livestock in the same huts that could hardly shelter them from wind and rain. Slave owners' houses had spacious courtyards surrounded by high walls, and some of them were protected by several or a dozen pillboxes.” [Source: China.org]

Yi Food and Wine Drinking

Yi house

The Yi do much of their cooking over wood fires on stoves made from bricks. Boiled pig head is a Yi specialty. After a meal is finished, guests are offered the remains of the pig head. It is considered to be most impolite to refuse. The Yi have traditionally been very poor and boiled potatoes without salt was considered a good meal.

Among the staple food of the Yi are corn, buckwheat, oats, and potatoes. Rice is not eaten as commonly as it is among other Chinese groups. The Yi raise and grow their own livestock, poultry, and vegetables. Few vegetables grow on the high plateaus, where many of them live, but some wild herbs found near them are edible. The Yi like spicy and sour food and didn’t get enough salt in the past. They make wine from corn and buckwheat and like baked tea.

In the old days, according to the Chinese government, “Most poor Yi peasants lived on acorns, banana roots, celery, flowers and wild herbs all the year round. Salt was scarce. In the Yi areas, potatoes cooked in plain water, pickled leaf soup, buckwheat bread and cornmeal were considered good foods, which only the well-to-to Yis could afford. At festivals, boiled meat with salt was the best food, which only slaveowners could enjoy. Cooking utensils of a distinct ethnic color, made of wood or leather, have been preserved in some of the Yi areas. Tubs, plates, bowls and cups, hollowed out of blocks of wood, are painted in three colors — black, red and yellow — inside and outside, and with patterns of thunderclouds, water waves, bull eyes and horse teeth. Wine cups are hollowed out of horns or hoofs. [Source: China.org |]

The Yi enjoy drinking wine. Wine plays an important role in their diet and social life. According to a Yi saying: "Han people value tea, Yi people value wine." It is as common for the Yi to entertain guests with wine as it is for Han to entertain guests with tea. Other Yi sayings say: "Wine is dish" and "Where there is wine, there is feast, and butchered pig and sheep can't make a feast if there is no wine". Yi people drink wine as part of their normal life, and in welcoming and entertaining guests. Wine is a fixture of New Year celebrations, festivals, wedding parties, funerals, happy occasions, consulting great events, and in mediating quarrels. For the Yi wine exists almost everywhere. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

There are many ways for the Yi to drink wine. "Drinking in turn" and "drinking with bamboo straws” are two special customs of the Yi. Wine of the Yi is generally made from sorghum, corn and buckwheat mixed with distiller's yeast in jars. When the wine is mature, the sealing mud is removed from the jars, and cold boiled water is placed in it. The Yi put bamboo straws in the jars and drink by sucking on the straws. This is called "drinking with bamboo straws". ~

Yi people don't like to pour and drink wine alone. They like to gather and drink together at a variety of times and places. They often gather in threes and fours, sit down on ground to form a circle, and drink from the left side to the right side, sharing the same cup, bottle or bowl. Every one wipes the brim of the cup or bowl clean with left hand as courtesy after drinking, and then hand it over to the person nearby. Sometimes they drink in turn directly from the wine bottle. This way of drinking wine is called "drinking in turn". ~

Yi Culture and Art

Yi lacquerwares

Yi culture and art includes works on history, literature, medicine, and chronologies written in the Yi language. Traditional crafts arts include embroidery, lacquerware, making silver accessories, carving, and painting. Cooking utensils were usually made of leather or wood. Tubs, plates, bowls, and cups were handcarved and then painted inside and out with black, red, and yellow colors. Wine cups were carved from cattle horns or hooves. The Yi invented an original writing system. Hundreds of manuscripts in Yi writing have been published.

Yi lacquerwares is well-known Many domestic utensils, such as wooden dishes, plates, bowls, cups, spoons, and flagons, are painted vividly with decorative figures and patterns in black, red, and yellow. Typical patterns included waves, thunderclouds, bull's-eyes and horses' teeth. A painted lacquer dinner set at the Shanghai museum consists of 22 pieces carved by Yi living in Sichuan. The painted red, yellow and black designs and colors have symbolic meaning in their culture.

According to the Shanghai Museum: The painted patent leather armor of the Yi people in Liangshan is made of cowhide and is tailored in accordance with human body shape, similar to the mirror armor of the Tang dynasty. Its front and back are made of a large piece of leather, with four smaller rectangular pieces beneath them to protect the abdomen and waist, further below are six layers of armor made of 300 small pieces of cowhide densely overlapped. Black, red, and yellow are the basic colors of leather armor of the Yi people. Yi people adore black. Black stands for ‘noble’; red represents propitious portent, a symbol of courage and fearlessness; yellow means good luck, beauty, and bright. There are about five patterns on this armor: the breastplate is decorated with vortex patterns on both sides, known as ‘bull eye pattern’; there is a striking crown-like image in the middle part, called ‘cockscomb pattern’; the rim is decorated with three kinds of patterns, including star, rapeseed, and plant, meaning flowering and auspicious, which is related to the Yi people’s belief that the bull and cock are sacred animals. Joined together with leather ropes, the leather armor has a quaint style and thick texture. [Source: Shanghai Museum]

Dancing is regarded as both a form of recreation and a cultural expression. The Moon Dance of Axi is probably their most famous dance and has been performed frequently on stages abroad. A popular dance, called Tiaoye, is a form of collective dance.. Yi women do a circle dance with yellow parasols. Yi men like to play a card game called Doushisi (“Fighting Fourteen”). There are many other dance styles and scenarios. Performers usually sing while dancing. Wrestling, arrow-shooting, top-spinning horse racing, tug-of-wars, buffalo fighting, cock fighting and a variety of ball games are popular sports with the Yi.

Yi Folklore

According to the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”: Yi mythology, like that of many other national minorities of China, centers around the flood and the origin of human beings. However, many aspects of the myths reflect Yi customs and political conceptions. For example, in "The Story of the Flood," the god Entiguzi and his family live in Heaven and ruthlessly rule the people on earth, who are too poor to pay their taxes. Following a dispute, three brothers beat a tax collector to death. Thereafter, when they ploughed their field, the next day the field reverted to untilled soil. They worked hard for three days, but all their efforts were in vain. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

One night they discovered that it was an old man who restored the ploughed field to virgin land. The two elder brothers wanted to kill him, but the younger brother asked the old man why he was doing this. The old man told them it was useless to plough any more, because Entiguzi in Heaven had decided to flood the earth. They were to build three ships made of iron, copper, and wood, respectively. However, when the flood came, only the youngest brother, Wuwu, escaped death by sheer luck. As the only survivor on earth, Wuwu told Entiguzi that he hoped to marry his daughter. Entiguzi refused. Since Wuwu rescued a great many animals from the flood, they helped him to go to Heaven. He met Entiguzi's youngest daughter. They fell in love at first sight. Entiguzi had no alternative but to agree to their marriage. Later on, she gave birth to three sons. The eldest was the ancestor of the Tibetans, the second of the Chinese, and the third of the Yi. ++

“Another Yi myth of origins, centering on the "Tiger Clan," spread in Yunnan Province. It also begins with a god opening the doors of Heaven to flood the earth. Later, the god opened a calabash and found a brother and a sister inside. Yielding to the god's will, they married. The woman gave birth to seven daughters. One day, a tiger came and asked to marry one of the girls. Only the youngest daughter was willing to marry to ensure the continuation of mankind. The tiger took her away to the mountains. After entering a cave, the tiger was transformed into a good-looking young man. The woman gave birth to nine sons and four daughters. Her nine sons were the ancestors of nine nationalities, among them the Yi. The Yi are described as living in the mountains, as being hunters and pastors, and as being fond of buckwheat and corn. The burial customs of the Yi are linked to the Tiger myth. The Yi still believe that the dead should be cremated, for only cremation will transform the dead into tigers. In some Yi districts, the corpse should be covered with tiger fur to recall that the deceased was the descendent of a tiger and will revert to being a tiger after death. The myth of the "Tiger Clan" is probably the remnant of totemic worship of the tiger in the remote past. ++

The Nuosu are the largest division of the Yi ethnic group. Their creation epic plots the origins of the cosmos, the sky and earth, and the living beings of land and water.“The Nuosu Book of Origins: A Creation Epic from Southwest China” — translated by Mark Bender and Aku Wuwu from a transcription by Jjivot Zopqu (University of Washington Press, 2019) — is a translation of this epic. The Book of Origins is performed by bimo priests and other tradition-bearers. Poetic in form, the narrative provides insights into how a clan- and caste-based society organizes itself, dictates ethics, relates to other ethnic groups, and adapts to a harsh environment.

Yi Wine Vessels

The Yi people attach much attention to the beauty of drinking vessels. The lacquer wine vessel is beautiful and useful example of this . Yi lacquerwar has a 1600 year history and includes wine pots, wine cups, wine plates and wine spoons. The roughcast is generally made from wood, feather or horn, and the inside and outside are coated with colorful lacquer. Usually black lacquer is painted as a background, and red or yellow patterns and designs are painted on it. One of its characteristics of Yi lacquerware is the tone is terse, bright and clear, and the decorative patterns are natural and realistic. Among the most common figures are the sun, moon, mountains, rivers, flowers, birds, worms, snakes, plants and domestic and wild animals. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

Yi wine pot and cups come in many shapes and sizes. There are round pots, flat-bottomed pots, pot with long legs, and all kinds of bird-shaped and fish-shaped pots. There are round leg cups and long leg cups. Some cups are made of animals hooves or bird's claw, such as the cup of eagle's talons or wild goose's talons. What is particular is unique about some Yi wine vessels is that they don’t have an obvious mouth for pouring the out wine. ~

People insert a bamboo straw into the upper part of the pot, which reaches the bottom for sucking wine. The mouth for pouring in the wine is at the bottom. There is a little hole at the middle of the bottom. A bamboo straw is put in it, which reaches the shoulder of the pot. When wine is poured into it, the top of the vessel is plugged and turned upside down. Wine wine is poured into the hole and the vessel is then put upright. The wine doesn’t leak out and doesn’t evaporate. The design is so ingenious that people often don't know how wine is poured into the pot even after they have drunk the all wine. Many bamboo straws are inserted around the body of some pots, but only one straw is for drinking. The others are decorations. ~

Yi Clothes

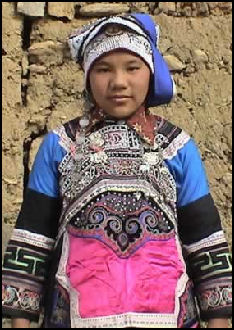

Yi women wear embroidered blue pleated skirts, short-sleeve jackets with colorful swirling patterns, gold and silver ornaments and large, black, five-pointed, fabric-covered hats that look sort of like nun habits and are made of four kilograms of knitted wool. According to some Yi the hats were devised by men who thought woman’s brains were getting too big. Women are also fond of wearing ornaments, particularly earrings and a hand-sized, finely carved silver plate attached right below the collar.

Yi women wear embroidered blue pleated skirts, short-sleeve jackets with colorful swirling patterns, gold and silver ornaments and large, black, five-pointed, fabric-covered hats that look sort of like nun habits and are made of four kilograms of knitted wool. According to some Yi the hats were devised by men who thought woman’s brains were getting too big. Women are also fond of wearing ornaments, particularly earrings and a hand-sized, finely carved silver plate attached right below the collar.

Men mostly wear black clothes with narrow sleeves and a wide front and long trousers with baggy legs. Women often wear garments with a wide front and a long pleated skirt. Yi women are skilled at weaving clothing, making garments and decorating them with embroidery. The upper three parts of their long skirts are made of cloth of different colors. The fourth part is pleated.When they go out, both men and women wear black wool or felt cloaks, called ca'erwa", which are decorated by a long fringe at the bottom.

Yi clothes and adornments are varied and different in different places. By one count there about different 100 categories of Yi clothing. In the Liangshan Mountains and west Guizhou, men wear black jackets with tight sleeves and right-side askew fronts, and pleated, wide-bottomed, baggy trousers with a ‘hero bun’ on the head symbolizing man's dignity. Men in some other areas wear tight-bottomed trousers. They grow a small patch of hair three or four inches long on the pate, and wear a turban made of a long piece of bluish cloth. The end of the cloth is tied into the shape of a thin, long awl jutting out from the right-hand side of the forehead. They also wear on the left ear a big yellow and red pearl with a pendant of red silk thread. Beardless men are considered handsome. Women wear laced or embroidered jackets and pleated long skirts hemmed with colorful multi-layer laces. [Source: China.org |]

Black Yi women used to wear long skirts reaching to the ground, and women of other social ranks wore skirts reaching only to the knee. Some women wear black turbans, while middle-aged and young women prefer embroidered square kerchiefs with the front covering the forehead like a rim. They also wear earrings and like to pin silver flowers on the collar. Men and women, when going outdoors, wear a kind of dark cape made of wool and hemmed with long tassels reaching to the knee. In wintertime, they lined their capes with felt. But few slaves could afford clothes of cotton cloth, and most of them wore tattered home-spun linen. |

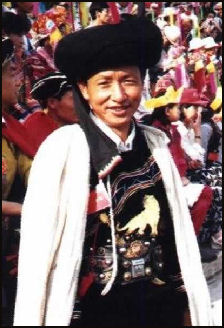

Yi men favor long, loose jackets, sarongs or pants, full-length capes and black or red turbans. The jacket can be white, plain blue or black with contrasting braiding and decorations. Shaman sometimes where huge black hats that look like a cross between a sombrero and a turban Men's clothes can vary according to regions. In some places, , men wear multi-pleated loose pants; in others, they wear tight ones. A braid enclosed by cloth on the men's foreheads is an important symbol of identity. Some men y wear a large earring of red or yellow on their left ear.

Yi Men’s Clothes: Turbans, Cloaks and Wide-Leg Trousers

The basic style of clothing for Yi men: 1) a long cloth wrapped around head like a turban; 2) a close-fitting top with wide front, covered by a "Ca'erwa" wool cloak or a felt cloak; and 3) long trousers. This kind of dress is unique to the Yi. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

Yi men have traditionally had long hair, which they coiled at the top of the head and and wrapped in black or dark blue cloth. Some still wear their hair in this fashion today. The cloth is several meters long and the end of it is bound into an awl-shaped black horn, which is set up above the forehead. This is called "Zuotie" in Yi language and "Hero knot" in Chinese. The coil and the hero knot are regarded as holy things and should not be carelessly touched. Yi men generally go beardless. Some wear big bead earing from their left ear as a decoration. ~

Yi men in Liangshan region like to wear a "ca'erwa" cloak. A ca'erwa is like a cape. Reaching below the knees and decorated with long tassels sewn around the edge, it is woven from wool yarn and is usually black in color. Covering the shoulders, back, arms, and even the chest and legs, it keeps out bright sunshine on sunny days and resists water on rainy days. It serves as a kind of clothes when going out and a quilt when sleeping. ~

The trousers worn by Yi men are distinctive and characteristic. One feature that is unique is that the width of leg varies. There are three main kinds: large, medium and small, and the differences usually indicative of where the Yi come from or which group they belong to. Meigu, Ganluo, Leibo, Ebian, Mabian in Sichuan and Qiaojia, Yongshan in Yunnan are commonly called "large leg" region. Men's trousers legs are very wide there, with widest being about 170 centimeters, much wider than normal women's skirt. If you grab the edge of these large trousers, you can draw it up to the side of head and it forms a shape of fan. The quantity of cloth needed to make them is seven to eight times the cloth used in making normal trousers. Mianning, Xide and Yuexi in Sichuan are called "medium leg" region. The legs of these trousers still very wide— usually 60-100 centimeters wide—and still looks like a skirt. Even the trousers worn in the so-called "small leg" region— including Puge, Butuo and Jinyang in Sichuan—are wide. The bottoms of trousers legs are relatively narrow, but the waist and crotch are still very wide, and the trousers themselves resemble riding breeches. ~

Yi Women’s Clothes

Yi women often wear 1) a scarf, wrapping cloth or hat on their heads, 2) tops with wide fronts and 3) long pleated skirts that reach to the ground.

Their garments are often embroidered or trimmed at the edge with cotton lace. Below the knee of their multi-pleated long skirts are cloths of different colors. Teenage girls cover their head with a black kerchief; young and middle-aged women usually wear an embroidered square kerchief.

Yi women often wear 1) a scarf, wrapping cloth or hat on their heads, 2) tops with wide fronts and 3) long pleated skirts that reach to the ground.

Their garments are often embroidered or trimmed at the edge with cotton lace. Below the knee of their multi-pleated long skirts are cloths of different colors. Teenage girls cover their head with a black kerchief; young and middle-aged women usually wear an embroidered square kerchief.

Yi girls in the Honghe region in Yunnan begin wearing cockscombs at the of three years old, and change to a wrapped scarf after they get married. Their elegant cockscomb hats are made by cutting hard cloth into the shape of cockscomb and sewing more than 1200 silver bubbles of different sizes on the hard cloth. These days, many Yi females embroider the hat with colorful silk thread or top the hat with colorful knitting wool instead of using the silver bubbles. The girl wearing this headgear look like crowing cocks.

The legend describing the origin of cockscomb headgear goes: long ago, there was a couple of Yi youth who were in love with each other. On a night with bright moon and quiet wind, they came to forest to meet, and were discovered there by the devil king. In order to claim the beautiful girl for himself, , the devil king killed the fellow. To keep her honor, the girl fled for all she was worth, but the devil king chased after her. When the girl reached the edge of her village, she suddenly heard the loud crow of a cock. When the devil king heard the crow he suddenly stopped, and the girl succeeded in escaping. After that the girl knew that the devil king was afraid of cocks. She went to the place her boyfriend disappeared with a cock in her arms. When the cock crowed loudly her lover came back to life miraculously. The girl and the fellow got married and lived a fine and happy life. From then on, local girls started to wear cockscomb hats, which symbolizes good luck and happiness. It is said that the silver bubbles on the hat stand for stars and moon, and symbolize eternal light and happiness.

The pleated skirts of the Yi are extraordinary. They are pieced together from two or three sections of cloth with different, often sharp contrasting, colors. In Meigu, Ganluo, Leibo, Mabian and Ebian in the "large leg" region, children's skirts usually have two sections— red and white— and the skirt is edged with one thick black strip of cloth and one thin black strip of cloth. When the girls are fifteen or sixteen, a skirt-changing rite is held. The girls begin wearing an adult pleated skirt with three colors connected from the top to bottom. Adult skirts are generally about 90 centimeters long. The upper section hugs the waist; the middle section appears tubular; and the lower section fans like a skirt. The three sections all have pleats and the lower section is wider and has more pleats. These skirts are mostly red, yellow, green, pink, blue or black.

The pleated skirt of the medium leg region— such as in Ninglang in Yunnan—is almost the same as that of the large leg region. The young women's skirt is often pieced together with red, yellow, jade green, rose-red and pink cloth alternating with white cloth. The skirt reaches the ground, hiding the feet and sweeping the ground with a brushing sound. A triangle-shaped pouch embroidered with applique hangs on the waist, and colorful arrowhead-shaped streamers hang down the pouch. It is not only an adornment but also a pouch for holding tobacco and sundries. The color of middle-aged and old women's skirt is not so strongly contrasted and is plain and neat. The old women's skirt is generally pieced from black or blue stripes of cloth, alternating with white.

Yi women in the medium leg regions and the small leg regions of Butuo, Puge, Jinyang, Ningnan, Huidong, Huili in Sichuan and Yuanmou, Huaping in Yunnan weave a kind of wool skirt by themselves. The waist of the skirt is made of white double-layered coarse cloth, and the middle and lower sections are made of cloth woven with wool yarn. The quality of the skirt is soft and thick. The middle section is often dyed red or yellow and the lower section retains the original color or is dyed black. The upper two sections have no pleats or a few pleats. Only the lower section has fine and close pleats.

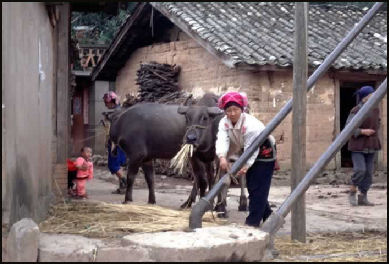

Yi Economy, Agriculture and Livestock

The Yi have traditionally been subsistence farmers who did some crafts such as coppersmithing and woodwork in the agricultural off season. Potatoes and maize are the staples of the Yi diet. Buckwheat, wheat and oats are also grown. Acorns, wild greens and herbs are collected in the forest; sheep, goats, pigs, cattle are raised; and hunting and fishing were practiced. Traditionally, slash and burn agriculture was employed and little fertilizer was used. The Yi believe that if they bathe their crops won't grow. [Source: Ian Skoggard, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

Most Yi engage in farming but some engage in. raising domesticated animals in grasslands and forested areas. In the Liangshan ranges livestock includes cattle, sheep, goats, horses, pigs, and chickens. Sheep and goats were the most numerous. They are raised for meat and wool. Goat herders typically spend seven hours a day every day with their animals in the mountains. Families sell goats and cows in Lijang and other cities and use they money to buy salt, tea, rice and clothing.

Many Yi grow wheat in the winter and spring and rice in the summer and fall. After the wheat is harvested the land has to be prepared for rice. Villagers help each other out. Harvesting and threshing is still largely done by hand. When they are working in the fields they often prepare their meals and eat there. Fishermen lay out nets in the rivers and guard them by sleeping in small shacks near the nets. Hunters often go out all day and return empty handed. Pigs are fed stewed scraps in a hollowed out log that serves as a trough.

One Yi villager told Nature Conservancy magazine: “Our Jiyu Village is an administrative village. It has the most croplands in the Lashi Township. So we grow and harvest more grain and cash crops here. Naturally more cropland means more hard work in the fields. During harvest time, crop dealers come to buy farm crops like flour, corn and beans, because the people in Tai’an only grow potatoes, we sometimes go there to sell our grain crops or exchange with people there for their potatoes.”

Because the Yi live in such a rough environment — mainly on high plateaus — and their agriculture technology is often relatively basic and the areas they live are often hard to reach it is hard for the Yi to generate a developed economy. Better transportation has helped the problem somewhat but to seek a better life the Yi generally have to leave their mountainous home, leave their traditional life behind and move to the cities.

Sani and Ashima

The Sani is a group with about 40,000 people concentrated mainly in the Guishan mountains of Lunan County, now known as Shilin (Stone Forest) County, in Yunnan, 80 kilometers from Kunming. The Sani are one of the most well known ethnic groups. Some regard them a separate ethnic group but most considered a branch of the Yi. They are also known as the Nir. The Sani are well known because live around the labyrinthine karst formations of the Stone Forest, near Kunming, and they have also preserved their traditional culture. They have been studied in great detail by anthropologists such as the Paul Vial from France and Ma Xueliang from China. The Sani are well known in China because of the story of Ashima, which was made into a popular, propagandist movie in 1964. Although Ashima is not a true work of Sani literature, the topic, a young girl abducted by a landowner to prevent her from marrying her lover, who is killed afterwards, was used by the Chinese Communists Party to convey their revolutionary message. [Source: Ethnic China *]

The Sani language belongs to the southeastern dialect. Sani clothes have a unique style. Men usually wrap their head with black cloth, cover their legs with black trousers and wear a jacket with cloth buttons down the front over a a sleeveless flax garment with buttons down the front. Women wrap a piece of cloth around their head which appears a little square with a board as framework, cover their legs wear long trousers instead of skirt and wear clothes with wide front, and drape a sheep skin cape over shoulders. The Sani people are especially good at singing, flute playing and dancing. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

The fact that the Sani are lumped together with Yi is a matter of some controversy. Many Sani do not even know that the government considers them Yi. To themselves and everyone around them the Sani are the Sani. The language of the Sani is quite different from other Yi groups. Some people have said that the Sani feel confused when someone calls their attention to the fact that on their hukou (identification card) their "nationality" is designated as "Yi". Most of these cultural characteristics that are used to link the Sani with the Yi are common among many other peoples of Yunnan, such as : 1) Enjoying sexual freedom before marriage; 2) an uncle's preference for marrying his niece to his son; 3) the importance of clan structure in their society; 4) the celebration of the Torch Festival; 5) Existence of shamans called "bimos", and other religious specialists. *\

Ashima is a character in Yi folk legend particularly associated with the Sani. According to the long folk narrative poem "Ashima" she grew up in a common family, and had a brother Ahe (in some versions of the story they are not brother and sister but lovers). They were very clever, diligent and kind-hearted since childhood. When Ashima grew up and became a beautiful girl, the ruler Rebubala wanted her to marry his son, but she refused him. Rebubala was shamed into anger and kidnapped Ashima, who said she would rather die than submit to him. Ahe fought fiercely against Rebubala and saved Ashima. But on the way back home, Rebubala persuaded the Rock God to produce a flash flood and Ashima drowned. From then on, Ashima became an echo which "doesn't disappear even if the sun disappears, and doesn't stop even if clouds stop". This echo reverberates ridges and mountains of the Sani region forever. In the 1950s, the "Ashima" story was translated and published in Chinese, Russian, French, English, Japanese and other languages. In the 1960s it was made into film. Nowadays, everyone in China knows the name Ashima and her story. ~

There are at least two English translations of "Ashima", one published by the Yunnan Nationalities Press (2000) and another by China Literature Press (2000).

Image Sources: VPO Yi website; Nolls China website; Johompas; Darmouth College, Wiki Commons

Text Sources: 1) “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China”, edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company; 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China *\; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2022