JINGPO ETHNIC GROUP

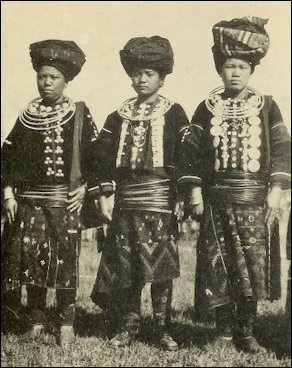

Kachin-Jingpo Ladies

The Jingpo is the name of a minority that lives in Yunnan Province along the northeast border of Myanmar. There are also large numbers of them in Myanmar where they are known as the Kachin. There are also a few thousand in Assam, India where they are known as the Singhpo. The Myanmar Kachin have always constituted the main part of the people.

In China the Jingpo live almost exclusively in Yunnan on the slopes of mountains between 1,470 meters and 1,980 meters in the Dehong Dai and Jingpo Autonomous Prefecture, a region filled with monsoon rain forests and dominated by the Gaoling Mountains and Daying and Ruili Rivers . The mountains run south and southwest, diminishing in elevation from more than 2,940 meters in the north to less than 210 meters at the southwest outlet to the Irrawaddy Valley. The Dehong terrain is a fan-shaped slope that captures the rain-producing northeastern monsoon of the Indian Ocean, which creates a rich subtropical rain-forest area. The climate is semitropical with most of rainfall in summer. The average annual rainfall is 200 centimeters. People here used to divide a year into only two seasons: a dry season from November to May and a wet season from May to October. The fertile land and plentiful produces a lot of things. Apart from dry rice, paddy rice and corn, there are rosewood, nanmu and a variety of bamboos. Economic plants include rubber, tung tree, coffee, tea, citronella. Among the tropical and subtropical fruits that grow well are pineapple, jackfruit, mango, banana. Various kinds of rare birds and animals live in the deep forest, and plentiful mines are buried in the ground. [Source: China.org; [Source: Wang Zhusheng, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

The Jingpo in China live in Yunnan Province: mainly in Luxi, Longchuan, Yingjiang, Ruili, Lianghe Counties in Dehong Dai and Jingpo Autonomous Prefecture, while a few are scattered in Lancang, Tengchong, Gengma and the Nujiang Valley and other prefectures and counties. The Jingpo that reside in Dehong Dai-Jingpo Autonomous Prefecture live together with the De'ang, Lisu, Achang and Han peoples. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences]

The Jingpo people are known in China for their hard working character, hospitality and bravery. They have a widely known proverb: "Be as brave as the lion." According to Chinese government: “They explore nature with their diligence and fight against enemies with their broad swords. In history, they have fought against invaders several times, and made considerable contributions to protection of the Motherland.”

The Jingpo are the 34th largest ethnic group and the 33rd largest minority out of 55 in China. They numbered 147,828 in 2010 and made up 0.01 percent of the total population of China in 2010 according to the 2010 Chinese census. Jingpo population in China in the past: 132,158 in 2000 according to the 2000 Chinese census; 119,209 in 1990 according to the 1990 Chinese census. A total of 101,852 were counted in 1953; 57,762 were counted in 1964; and 100,180 were, in 1982. About half of Jingpo live in Longchuan County, Dai-Jingpo Autonomous Prefecture. There is no good figure on their numbers in Myanmar but it estimated that there are more than a million of them there. [Sources: People’s Republic of China censuses, Wikipedia]

See Separate Articles: JINGPO LIFE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com ; KACHIN MINORITY factsanddetails.com ; KACHIN LIFE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Kachin News kachinnews.com ; “The Kachin: Lords of Burma's Northern Frontier,” by Bertil Lintner, Teak House Publications, 1997 Bangkok.; Book Chinese Minorities stanford.edu ; Chinese Government Law on Minorities china.org.cn ; Minority Rights minorityrights.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Ethnic China ethnic-china.com ;Wikipedia List of Ethnic Minorities in China Wikipedia ; Travel China Guide travelchinaguide.com ; China.org (government source) china.org.cn ; People’s Daily (government source) peopledaily.com.cn ; Paul Noll site: paulnoll.com ; Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science Museums of China Books: Ethnic Groups in China, Du Roufu and Vincent F. Yip, Science Press, Beijing, 1993; An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of China, Olson, James, Greenwood Press, Westport, 1998; “China's Minority Nationalities,” Great Wall Books, Beijing, 1984; Book: “Leaf-Letters and Straw-Bridges: The Jingpos” by Jin Liyan, Yunnan education publishing house,china, 1995

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Jingpo “The Jingpo: Kachin of the Yunnan Plateau” by Zhusheng Wang Amazon.com; “Jingpo Folklore” by Tan You Gao Bian Amazon.com; Kachin: “The Kachins” by A. Gilhodes Amazon.com ; “The Kachin: Lords of Burma's Northern Frontier by Bertil Lintner Amazon.com; “The Kachins, their customs and traditions” by O. Hanson (1913) Amazon.com; “Mogaung Region of Kachin State (1752-1885)” by K.Khine Kyaw Amazon.com “Political Systems of Highland Burma: A Study of Kachin Social Structure by Edmund Ronald Leach Amazon.com “A Grammar of the Kachin Language” by O (Ola) 1864-1929 Hanson Amazon.com; “Handbook of the Kachin or Chingpaw Language” by Henry Felix Hertz Amazon.com; World War II and History “Joe Wolfe and the Kachin Rangers: Guerrilla warfare in WW II Burma” by John h Lambe Amazon.com; “Duwa Zau June: The Legacy of a Kachin Warrior: A World War II Story” by Z. Brang Seng Amazon.com; “Joe Wolfe and the Kachin Rangers (The American Scouts and Rangers “by John h Lambe Amazon.com; Mission in Burma: The Columban Fathers' Forty-Three Years in Kachin Country by Edward Fischer Amazon.com: Modern Separatism “Life Behind The Backdrop Of Kachin State, Myanmar” by Mr. Lisupha, Mr. G Burgard, et al. Amazon.com; “Quest for Freedom: A Kachin-American Experience” by Mr. Michael Jala Maran Amazon.com ; “The Kachin Conflict: Testing the Limits of the Political Transition in Myanmar” by Carine Jaquet Amazon.com

Jingpo Groups and Names

Dehong Dai and Jingpo Autonomous Prefecture

There are four main Jingpo subgroups: 1) the Jingpo (Jinghpaw in Myanmar); 2) Zaiwa; 3) Lachi; and 4) Langwo, with the Zaiwa and Jingpo being the major two. The 1990 census counted around 70,000 Zaiwa in China.

The Jingpo also call themselves Zaiwa, Laqi, and Polo in accordance with their different living areas. They are named "Dashan", "Xiaoshan", "Langsu" and "Chashan" by the Han people.The Kachin and Jingpo is also known as the Acha, Aji, Atsa, Kang, Lalang, Lashi, Maru and Shidong. The Kachin seldom refer to themselves as Kachin but rather describe themselves in terms of their own linguistic group, which are given as the Maru, the Lashi, the Atsi (Szi), the Lisu and the Rawang in Burma.

“The name "Jingpo" was officially adopted as the formal name in 1953. Before then the Han Chinese normally called this minority "Shantou Ren" (the people on the mountaintops) and, earlier, "Ye Ren" (savages or wild people). Why did the name Jingpo become synonymous with the entire group in China? In part because, in these related Kachin cultures, there is no written script for any of the various dialects. The Jingpo dialect was romanized in the late 1800's by Christian missionaries in Myanmar and for the Zaiwa branch in the 1950's. Therefore, both numerically and linguistically, the Jingpo have become the dominant of these many groups and the Jingpo dialect is used as a "lingua Kachinica" by those whose dialects are mutually unintelligible. Hence all Kachin in China have come to be known as the Jingpo. [Source: Ethnic China]

The Jingpo mainly inhabit tree-covered mountainous areas 1,500 meters above sea level in Dehong Dai-Jingpo Autonomous Prefecture in Yunnan Province. The climate is warm and there is plentiful rain. Countless snaking mountain paths connect Jingpo villages, which usually consist of two-story bamboo houses hidden in dense forests and bamboo groves. The area abounds with rare plants and medicinal herbs. Among cash crops are rubber, tung oil, tea, coffee, shellac and silk cotton. The area's main mineral resources are iron, copper, lead, coal, gold, silver and precious stones. Tigers, bears and leopards used to live in the region's forests. Pythons, pheasants and a variety of birds still do.

Chashan

The Chashan is a group usually considered a small branch of the Jingpo, but they have enough distinct characteristics to be considered as different ethnic group. There are only about 1,000 of them. They live mainly in They live mainly in Pianma County in Nujiang Lisu and Nu Autonomous Prefecture in western Yunnan Province in the Gaoligong Mountains in a narrow area along the border with Myanmar. [Source: Ethnic China*]

It is believed that the Chashan are the original inhabitants of the area they occupy because most of their geographical names are translations from the Chashan language. In Ming dynasty (15th century) historical records the Chashan are clearly established their homeland.In the 1950s, when the Minzu Shibie (minorities identification project)—the first major work of ethnic identification in China—was carried out, they were considered a branch of the Jingpo , but data emerging from new investigations makes us think that, in fact, they may be considered an independent ethnic group. *\

The Chashan do not consider themselves related to the Jingpo. They call themselves Ochang. The people that live around them call them Chashan. Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote in Ethnic China: “Possibly the denomination Ochang comes from the name given to this region during the Ming dynasty, which was later adopted for its residents. Not too far from the region the Chashan inhabit, another indigenous people have been living for centuries: the Achang.” Because their names are similar and they have other similarities, perhaps “the Chashan are, in fact, a branch of the Achang. Linguistic studies also show that the languages of the Chashan and the Achang are closely related. A detailed study of their legends and the ceremonies they use to accompany the souls of the dead to the land of the ancestors suggests that the ancestors of the Chashan separated from the ancestors of the Achang around the 13th or 14th century and, crossing the Gaoligong Mountains, settled down in the lands where they now live.” *\

According to Travel China weekly: “Building a house is a big event for the Chashan people. All villagers will come and help. It takes only one day to finish the wooden house. After completion, the host comes to the courtyard to shoot three times with his powder gun into the shy to announce the successful completion. Then, the host leads all family members to the entrance to wait for the arrival of guests. All villagers will come to congratulate with presents. The host presents every guests with a bowl of polished glutinous rice and other delicious dishes. Elderly people tell old stories on building houses in an attempt to educate young people to inherit the tradition and to unite like the polished glutinous rice.”

Origin and Migrations of the Jingpo and Kachin

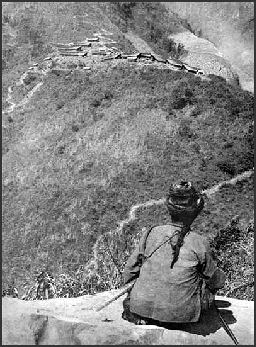

Kachin fighter in WW2

The ancestors of The Jingpo people are related to the ancient Di and Qiang on Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. The origin of the Jingpo is a matter of some debate. It is widely believed that they originated in the southern part of the Tibetan Plateau around the sources of the Irrawaddy, Mekong, Yangtze and Salween Rivers and began slowly migrating southward along the aforementioned rivers about 1,500 years ago into the northeastern part of Yunnan in areas west of the Nujiang River. In the 16th century they moved in large numbers to the thickly forested Dehong area. Many settled along the Burma border because there were lucrative jade mines there. [Source: Wang Zhusheng, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “Among those southbound migrants were the Jingpo, who entered Dehong in about the fifteenth century. The reasons for the southward movement were the harsh environment, feuds and violent reprisals among clans, segmentation of the lineages, and later on, avoidance of military service to the imperial court. Historians believe that many ancient tribal names in Chinese historical records apply to ancestors of the Jingpo: "Qiang," "Sou," "Cuan," "Wu Man," "Xinchuan Man," "Luoxin Man," "Ye Man," "Ochang Man," and "Shantouren." However, early historical records about the affiliation of the people are few and largely conjectural. The geographic location and some cultural traits suggest that Xinchuan Man, Luoxin Man, and Ye Man of the Tang time are probably the ancestors of the Jingpo. ”

Oral histories relate that the Kachin originally arrived in Yunnan from the southern part of the Tibetan Plateau from a a place named "Muzhashenglabeng", which means mountain with a flat top. These histories describe a place where there was snow year-round and even corn and barley could barely grow. Approximately 1,500-2,000 years ago the Kachin gradually migrated south along the Lancang (Mekong) and Jinsha (Yangzee) rivers before settling in their present locations in the 16th century in the northwestern part of Yunnan, west of the Nujiang River. After that, they split up into two parts, the eastern Kachin and the western Kachin. The eastern Kachin lived to the east of Lancang River and Jinsha River. And the western Kachin distributed in the area of Magulang and Gangfang, which in history was called Xunchuan, and in Han Dynasty was under the jurisdiction of Yongchang CountyThe local people, together with the newly-arrived Kachins, were called "Xunchuanman." They lived mainly on hunting.

History of the Jingpo

The first solid records of the Jingpo date back to the Tang dynasty (618-907). They became incorporated into China after the Mongols conquered Burma in the 12th century. After that the Jingpo were largely under the control of Dai overlords in accordance with the Chinese tusi system. In the Tang dynasty, the Jingpo and Kachin were described in historical records as the "Xunchuan" and "Gaoligong". Through the Yuan, Ming and Qing Dynasties until the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, they were called "Echang,” “Zhexie” and Yeren". “ Beginning from the 10th century, they migrated in large numbers to the Dehong area. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, they were formally named the Jingpo group. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities; [Source: Chinatravel.com]

Wang Zhusheng wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “ Before the Jingpo entered Dehong, the area had long been inhabited by other peoples: the limited fertile valleys were held by the Dai and Han, while the hills were the homeland of the De'ang (Benglong) and some Han Chinese. The dynasties had already incorporated the area into the tusi system, with the Dai as tusi lords. As unorganized, scattered immigrants, the Jingpo could find room to settle only in the mountains. As a whole, the Jingpo were subordinate to the Dai, and they had to pay tributes to the tusi in whose territory they lived. But since the tusi lands were fiefs of the imperial dynasties and the central court also had some direct relations with Jingpo chiefs, the Jingpo were only under the Dai tusi's nominal rule. Well-known as a warlike people, the Jingpo supplied important military support and services to the tusi and the central authority. Some Jingpo chiefs eventually gained the right to collect a "head-protection" fee from one or several Dai or Han villages as reward for their support or services. This pattern of spatial distribution and these sociopolitical interrelations between the Jingpo, Dai, and Han Chinese were maintained until the 1949 Revolution, and they still remain to a limited extent today. [Source: Wang Zhusheng, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

Kachin and Aung San

In the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), the Xunchuan area was under the jurisdiction of the provincial administration of Yunnan, which was set up by the central government. As they developed, various Jingpo groups gradually merged into two big tribal alliances — Chashan and Lima. They were headed by hereditary nobles called "shanguan." Freemen and slaves formed another two classes and bore the surname of their masters and During the early 15th century, the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), which instituted a system of appointing local hereditary headmen in national minority areas, set up two area administrative offices and appointed Jingpo nobles as administrators. Beginning from the 16th century, large numbers of Jingpo people moved to the Dehong area. Under the influence of the Han and Dai, the Jingpo learned to grow rice in paddy fields. [Source: China.org]

During World War II the Kachin earned high marks as fighters. They were skillful ambushers and had a cruel streak. They cut off the ears of the Japanese they killed as trophies. Their territory remained largely unoccupied by the Japanese. The Jingpo Autonomous Region was created in 1953 in southwestern Yunnan Province.

Jingpo Languages

The Jingpo speak a Sino-Tibetan language and have their own written language. There are a number of dialects. Some linguists assert that the Jingpo and Zaiwa dialects are different enough to qualify as different languages. Their written language is not used much anymore. Few people speak the native language in China anymore.

The Jingpo are divided into five language subgroups: Jingpo, Zaiwa, Leqi (Chasan, Chashan), Lang'e (Langsu) and Bola. These subdivisions refer to differences in language rather than ethnicity and are all branches of the Tibeto-Burman language family. In most areas, people from different subgroups live together. The language of the Jingpo subgroup belongs to the Jingpo language subgroup, Tibet-Burmese branch, Sino-Tibetan family. The other four are closer to each other, belonging to the Burmese subgroup, Tibetan-Burmese branch. In most areas, people from different subgroups live together. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities]

The language of the Jingpo subgroup belongs to the Jingpo language subgroup, Tibet-Burmese branch, Sino-Tibetan family. The languages of the other four subgroups are closer to each other, belonging to the Burmese subgroup, Tibetan-Burmese branch. Until around a century ago, when an alphabetic system of writing based on Latin letters was introduced, the Jingpo kept records by notching wood or tying knots. Calculation was done by counting beans.

Jingpo Pictographic Script

There are two kinds of writing systems: Jingpo and Zaiwa, both pinyin languages based on Latin letters. The former was created by American missionaries in 1895 based on the Jingpo spoken language but was not widely used.. This alphabet was reformed in 1957 by the Chinese government based on Jingpo who speak the Zaiwazhi dialect and has since been used in some Jingpo documents, newspapers, periodicals and books. Today, both sets of alphabetic system are still used by Jingpo people.

Jingpo script

The Jingpo have employed a naming system in which father's and son's names are linked. This system has traditionally appeared at the transition period from matrilineal clan system to patrilineal clan system.

Most on the Kachin Jingpo state that in the past they had no written language. However pictures of the lavishly decorated posts used by the Jingpo at the Munao Festival, the most important of their traditional festivals, feature unique pictograms. The Chinese scholar Shi Rui, through a meticulous analysis of these pictures and discussions of their symbolic meaning with Jingpo religious specialists, suggest that they represent a pictographic language used in Jingpo religious ceremonies. [Source: Ethnic China]

Every drawing or symbol on the Munao posts doesn’t have an isolated meaning but rather is part of a complete text that leads the shaman along in a ceremony. On an analysis of one set of three pictograms (1,2 and 3), Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote in Ethnic China: “1) It is read "pri" in Jingpo, and means "flash". 2) Its real meaning is "male", as "in the old times, when the heaven has not yet been formed and the earth has not yet took shape there was a man called the Man of the Obscure Times that in the middle of the dim flashed once. 3) This sign express the time of darkness. According to the explanations of the Munao ceremony words: before the creation of heaven, earth and all the creatures, the first that appeared was the Dark Man, he flashed once in the darkness. This is one of the earliest manifestations of the ancestor of the Jingpo. The creation of all the things in the world took consciousness from this darkness.” In the same way, Shi Rui has analyzed more than 30 signs painted on four Munao posts. [Source: Shi Rui.- Jingpo zu yuanshi tuhua wenzi (“Original pictographic script of the Jingpo Nationality”), Yunnan Fine Arts Publishing House. Kunming, 2007]

Husband and Wife: Speaking in Different Languages

Many Jingpo families are composed of members from different subgroups. There are traditional habits as to which language or dialect they use: father and children use that of the father's while the mother uses her own language. Although husband and wife can fluently speak each other's dialect, when they have conversations, they still stick to their own language, never giving up the right of using their own dialects. Conversations among children or between father and children are carried out in the father's dialect. When the children speak with their mother they use her language. If the grandmother is from different subgroup, conversations with her should all be carried out in her own dialect. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences]

When young people form different subgroups are dating, the man usually adopts the dialect of the girl to show his love and faith. But once they are married, they use their own dialects again. At school, the formal language is that of the majority subgroup, but students of the same subgroup still converse in their own language. ~

In the old days Jingpo people used to send message with certain items. For instance, a piece of meat with hair was a declaration of war, or meant victory or death of a person. When a young man wanted to express his love for a girl, he sent her a leaf, with tree roots, matchsticks, pepper and garlic in it. The leaf meant he had many innermost thoughts and feelings to tell her; tree roots expressed that he missed her endlessly; matchsticks implied he made up his mind; pepper represented his fervent love; and garlic meant he was waiting for her consent. If the girl accepted him, she sends the things back; if not, she puts charcoal in it. Nowadays, this simple custom can only be seen on special occasions. ~

Jingpo Religion

The Jingpo and Kachin have traditionally believed in a multitude of nats (spirits), gods and ghosts capable of bringing happiness or disaster to people. As a result, superstition and taboos are strong. Ceremonies addressed to nats accompany sowing, harvesting, disease, weddings, funerals and combat.” Shaman-priests preside over sacrificial ceremonies and serve as doctors. Sacrificial ceremonies are usually linked to agriculture. In China, some Jingpo are Christians. Some living among or near Dai people embrace Theravada Buddhism. In Myanmar, Many Kanchin are Christians. There is some tension between Catholic and Protestant groups.

At the root of Jingpo religion is belief in the dual nature of man and living things. The Jingpo believe that all the spirits were once mortals that have moved beyond the present world. Their existence in afterlife has given them supernatural powers and transformed them into objects of fear, reverence, and worship. There Spirits interfere in the world of living people by causing illness or good health, bring bad luck or good fortune, and determine the destiny of people. [Source: Wang Zhusheng, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

When a person dreams it is because the soul has abandoned the body. If the soul doesn't find anything interesting during its trip, the person will not remember the dream, but if there is an interesting experience, it is remembered on awaking. Dreams are very important amongst the Jingpo, who study them for ominous or auspicious meanings. There are some well recognized symbols used in interpreting dreams. For example, if a person dreams about a a knife or a rifle, it is a sign that the person will have a son. If a person dreams about a lot of cucumbers or pumpkins, it is a sign of suffering and bad things to come. After such a dream, a shaman is called for praying to the spirits. If not, one runs the risk of some possible death. [Source: Ethic China]

Each village has a sort of temple called Nengdang, which is usually made of straw. They don’t have any walls and are generally situated on the outskirts of the village. From them, cow and pig skulls are hanged. In the old days Kachin religioous festivals could be quite elaborate. In the pre-Communist era there were reports of ceremonies where a many as 27 cows were sacrificed. Such activities have been discouraged by Communists who consider them to be superstitious and a waste of resources.

Jingpo Spirits

Jingpo believe is spirits, called nats, which they believe are superior to human beings and were once human beings themselves. There are lots of spirits. They are everywhere, and individual villages and clans have their own ones that are capable of bringing good as well as evil. Nats are disagreeable creatures that are keen on taking revenge. They "bite" people who trespass against them, knowingly or unknowingly. As a result they are avoided and feared but also worshiped, and must be constantly thanked and appeased. Important deities include the Sky Nats who are children of the Creator. They include Madai Nat, the youngest sky nat, who can only be invoked by chiefs; Jan Nat, the female sun spirit; Ningawn-wa, the creator of the earth; and Madai Nat, the wife of the first Kachin aristocrat. [Source: Wang Zhusheng, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

The Kachin believe human beings are among the many kinds beings that exist on the natural world and each being has its own spirit. There are over 100 major deities in the Kachin pantheon. They generally fall into two main types: 1) Celestial Gods such as the God of Heaven, the God of Wind, the God of the Sun, the God of the Moon and the God of the Thunder; 2) Earthly Gods such as the God of the Water, the God of the Fire and the God of the Grain. Among all them the most important is the God of the Sun. Among their goddesses are Mother Creator, partner in creating the world; the Goddess of the Kitchen and the Goddesses of Intelligence, Music, Memory and of Maternity. In order to obtain beneficial results from so many deities and avoid trouble, a number of taboos are observed. [Source: Ethic China]

Jingpo dumsa

The very simple life of the Chashan is reflected in their religion. They believe in the existence of numerous spirits that are identified with different natural phenomena. Their primary god is the God of the Sky, Monke, who is above all the other deities. They worship Monke in all important ceremonies, particularly during weddings and funerals. When there are ceremonies in which the whole village participates, a cow is sacrificed for him. In smaller ceremonies in which only the family or the clan participates pigs or chickens are sacrificed. [Source: Ethnic China *]

After Monke, the second-most god in importance is Saiyou, the God of the Earth. He provides the Chashan with good crops and helps them to avoid natural disasters. He is worshipped mainly during the New Grain Festival. The God of the Mountains, Pengyou, is also important, since he is in charge of providing successful hunting, and protects the hunting parties when they leave the village. Therefore he is worshipped by the hunting parties before they leave for an expedition. The Chashan also have a God of Fire, a God of the Waters, a God of the Trees, and other nature deities. *\

The Chashan believe that in the world, good things are attributed to gods and bad things to demons. To keep demons at bay the Chashan have a series of incantations and curses. They have different prayers to worship the gods. In each Chashan village, there is a priest or Changsa, who is a specialist in dealing with spirits and the spiritual world. They know the desires of the gods and how to dominate the demons as well as incantations that should be recited in each ceremony. They also possess knowledge of medicine and tribal history, and are able to perform divination ceremonies. *\

Jingpo Shaman

Shamanism is still practiced by the Jingpo. The Jingpo have part-time religious specialists called dumsa (dongsha). They treat illnesses and other problems by identifying the nat that causes the trouble and determining the correct way to appease it. Dumsas are graded in terms of their perceived effectiveness by the public. In some ways the rankings are like those of priests, bishops and archbishops. There are also dumsa that specialize in certain kinds of nats, mediums, diviners, and prophets that specialize in certain kinds of religious practices such as sending souls. The latter are often female shaman, who go into trances when they do their work.

The most commonly recognized dumsa rankings are: 1) jaiwa (zhaiwa), or grand dumsa, the highest religious authority and the only priest who can officiate on special occasions such as manao (the greatest festival dedicated to the madai nat, the highest of all ancestor spirits); 2) the dumsa, who in turn are divided into several grades such as the ga dumsa, who can minister to the earth and sky spirit; tru dumsa, who can authorize the sacrifice to the ancestral spirits; and the normal dumsa; 3) the hkinjawng (qiangzhong), a subordinate and assistant to the dumsa often in charge of setting up the altar and cutting up the sacrifice; 4) the shaman-like myhtoi, the medium or nat prophet, who serves as an oracle and link to of the spirit world, who contacts nats while in a trance; and 5) the ningwaw t, the diviner. [Source: Wang Zhusheng, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Jaiwa are familiar with the history, myths, rituals and old culture. In the old days, they were influential figures, second in terms of power only to the village chiefs. Dumsa deal with the spiritual realm. Every village has traditionally had a dumsa. Ga Dumsa, also referred to big dumsas, specialize in heaven rituals. Tru dumsa and normal dumsa, also called regular dumsas and the little dumsas, perform ceremonies of lesser importance. Little Dumsas, cannot sacrifice cows or pigs, they can offer only chickens, dry fish and rats. Among the dumsa there is also shichao, a dumsa specializing in releasing and sending the souls of the dead to the spirit world. Some diviners are also dumsa, but usually good ningwawt are not.*\

According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “All of these specialists traditionally receive payment from their clients for their service. With few exceptions, these specialists are male, aged, and capable, with glib tongues, familiar with the religious language chanted at the sacrifice as well as everything about the history, tradition, and legends of their lineages and clans. The dumsa once were leading figures in the society. During the Cultural Revolution and other political campaigns, the dumsa had a difficult time, but now they are practicing again and make a fair income from their services.” |~|

Jingpo Funerals

Naoshuan wizard costume

The Jingpo believe that men have six souls and women have seven. Of these three are “real” and the others are “false.” If the real souls are absent a person dies. After death the real souls join the nat world. Dying a natural death at home is considered good while dying in an accident away from home ir regarded as bad, and likely caused by evil spirits. The Jingpo believe that some deaths are caused when spirits lure the soul away for the body and it can not be returned in time and the chord that binds the creator to an individual is eaten away by nats. [Source: Wang Zhusheng, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

The Kachin believe each person is divided into body and soul. After death, they believe, the soul leaves his body, and goes to the Kingdom of the Shadows, where it meet with its ancestors. According to their tradition, the Kachin come from the North and therefore, after death, the spirit should travel northwards. As it is a bad thing for a dead soul to stay among the living, many rituals are carried out to show the soul the way to the ancestors' land. At every Kachin home there is a house of spirits to which strangers are not allowed in.[Source: Ethnic China]

Funerals for a natural death at home involve burial and spirt sending. The spirit sending often necessitates the sacrifice of a buffalo and the placements of its skull at the grave. If spirits sending isn’t done, the Jingpo believe, the spirit will roam and cause trouble.

After death the family altar is removed from the house. Burial takes place a week after death to make sure that separation of the deceased’s soul from the world is complete. A priest presides over this process, making offerings to the soul to assist it on its journey to the next world. During a final ceremony a priest rouses the soul from temporary limbo and sends it to the land of the dead. Afterwards a divination ritual is held to make sure the soul has departed. If it hasn’t it will be installed in the family altar which is returned to the house.

Singing and Dancing to Mourn the Dead

When a shooting is heard in a Kachin village, it often means someone has just passed away. The Kachin can tell from the sound the gender of the dead (odd for a woman and even for a man). Having heard the message, neighbors and relatives immediately go over to help grieving relatives, taking grain, vegetables, fowls or cattle with them. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities]

There is no special ceremony when a young person dies. But if it is an old person with offspring, there is a grand ceremony to show admiration and love. On the first night of the funeral, people in the village and from other villages perform mourning dances ("Bengdong" in Jingpo, and "Gebenge" in Zaiwa) with the family of the deceased, which lasts until dawn. The more days of dancing, the more glorified the host. There are two dancing places: in and outside the house. People outside the house roar "wo-le, wo-le" loudly, moving wildly and powerfully, which implicates driving demons and devils away from the village. People in the house dance around the corpse, while singing dlow dirges, to the rhythm of a mang gong. There are over 30 body expressions in the dances, including pure witchery dancing, planting, hunting, fighting. The songs are not sad, but rather gay. Their contents includes complaining "why people should die", recalling the life of the dead, educating young generations on working hard and being a worthy person, and giving thanks for the efforts of ancestors to bring up the offspring. ~

People who die naturally are buried in the earth. Several months or years after the funeral, the family holds a ceremony to send back the soul of the dead — along the route on which ancestors moved southward, which mean the dead have to travel back to their hometown in the north. If the ceremony if for a respected old person, "Gebenge" ("Bengdong") is performed again, until the grave is finished. The grave traditionally consisted of a three-meter conical grass shed, with a wooden sculpture of a person on top. Colorful pictures were painted on the shed with charcoal, ruddle and pig blood, including the sun, the moon, mountains, waters, beasts, cattle, weapons, tools and crops to show the dead person's gender, age and main activities when alive. Bamboo sticks are put up around the grave, one for each of the deceased person's sons and daughters. The grave mound is built with blocks. When it is finished, there are no ceremonies any more.

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the funeral ceremony was simplified, to reduce huge expense and lost time that was spent on them. These days simpler funerals are the norm.

Jingpo Rituals amd Festivals

The basis of many Jingpo rituals is making sacrifices to the nats. Each village has dumsas that are in charge of such rituals. Two communal rituals, the numshang offerings, are performed each year, in April and in October, by most Jingpo villages. The rites are connected with a good planting season and a good harvest. There are ceremonies at other times that honor ancestors. Villages and individuals have their own nat observations.

Traditionally, individual households held rituals on a fixed timetable connected with the agricultural cycle. The ancestral nat offering in February aimed to bring good fortune in the coming year to the entire family. The offering in April was to guarantee growth of the rice seedlings. These were followed by ones in May to prevent the people being "bitten" by the spirit; the new-rice tasting ritual in October to thank the sky and ancestral nat; the rice-soul-calling-back ritual in November to ensure continued consumption of the rice. Families also perform situational and problem-resolving rituals held in conjunction with things like marriages, funerals, new-house building and special visits by religious leaders. A special "face washing" was conducted in cases of adultery or other sexual scandals. There are also problem-resolving rituals to dispel disease and bad luck, bring back a run-away wife, and to find lost things. |~|

In the Kachin region nat festivals known as manaus involve sacrificing large numbers of animals. Those in attendance wear their most beautiful and colorful costumes. In a large gathering 29 water buffalo may be sacrificed — one buffalo for each of the 28 nats honored and one for all the nats together. Before the sacrifice offerings of rice, eggs and wine placed in bamboo tubes are made. The buffalo is then ritually slaughtered, and its skull and horns are placed on a X-shaped pole. To the music of gongs and flutes the participants do a snake dance around the pole with the buffalo skull, as well as around nat poles which are reminiscent of totem poles. During the snake dance, which is led by chiefs wearing feathered head dresses, the dancers often go into trances.

Wang Zhusheng wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “The Jingpo commonly did not observe manau, “partly because it required seven to nine buffalo or cattle, tens of pigs, and hundreds of fowl as sacrifices, but also because only the madai-keeper families (i.e., those from the main chief lineages) were entitled to hold it, and only the jaiwa were entitled to conduct it. The government authorities banned this grand ritual in the Cultural Revolution. Now the government has officially declared the manao a Jingpo national holiday and fixed it on the Chinese New Year; its celebration is officially organized with no nat-offering activities. [Source: Wang Zhusheng, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

"Munao Zongge" Festival

The Jingpo love to sing and dance and have a good time and their friendliness and generosity comes out in their festivals. Munao, derived from manau described above is a massive festival held in the middle of the first lunar month in conjunction with the Chinese New Year, on an even-numbered day. This is called "Munao Zongge", and it is the biggest and grandest Jingpo festival. The word Munao comes from Jingpo language while Zongge comes from Zaiwa language. "Munao Zongge" is usually translated as meaning "dancing in mass". In the old days it was held before setting out for battle, returning in victory and mark good harvests, weddings, funerals and welcoming honorable guests. There are several legends describing its origins. One goes: Long long ago, the Jingpo people lived a peaceful and happy life. Then a devil, who fed on little children, appeared. One day, having no child to eat, he called wind and rain to form a flood, which drowned fields and houses. A man named Leipan helped his people escape by leading them to the Mailikai River and Enmeikai River, where they built new and settled. The devil eventually found them and devoured Leipan's son. Leipan vowed revenge and became determined to fight the devil to the death. The God of Sun was so moved that he made a sword for Leipan and the devil was killed. People celebrated with singing and dancing. Since then, the Jingpo have marked important events with singing and dancing gatherings called "Munao" to commemorate the glorious deed of their ancestor Leipan slaughtering the devil. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

A Munao usually last for three days. Everyone gathers in the Munao square to dance happily day and night. In the centre of the square are four Munao pillars that are around 20 meters high. On the pillars are various kinds of patterns: broad swords, triangles and symbols of luck, happiness, community and bravery. There is a square stage on the left side of the pillars, for musicians. A two-meter-long drum and one or several one-meter-in- diameter mang gongs are hung on the pillars. Around the square is a bamboo fence with two doors, preventing "wild ghosts" and the cattle from entering the square. ~

The festival starts with cannon salutes and loud music. People gladly offer wine and exchange gifts with each other. Two reverential old men—holding shining broad swords in their hands— wear loose dragon robes and Munao hats decorated with teeth of wild boars and feathers of peacocks and pheasants. Under their leadership, people dance according to the patterns and lines on the pillars. After two circles they are divided into two groups. One group dances under the leaders according to the pre-assigned route, while the other group are led by persons of high skills to dance in a freer way. Later, at the climax of the event, all the dancers dance with various kinds of flowers in their hands. Those in charge of cooking hold pots and scoops in their hands while those in charge of wine take wine barrels in their arms.

Munao in China used to have a strong religious character. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the festival became more of a secular event of all Jingpo people. Both the contents and the forms have changed. In addition to traditional Munao singing and dancing, there are a variety of entertaining performances and markets.

Image Sources: Kachin Myitkyina website, Nolls Chiina website, Beifan Joho maps

Text Sources: 1) "Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China", edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K.Hall & Company, 1994); 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2022