ACHANG MINORITY

The Achang are a small minority that live in the western Yunnan along border of the northeast Myanmar. They live in an area dominated by the Dai and Jingpo and have many cultural similarities with these groups. The Achang are also known as the Daisa, Hansa, Menga, Ochang, Atsang and Menga-shan. The ancestors the Achang were hunters and gatherers. According to Chinese records they originated in northern China and began migrating southward about a 1,000 years ago and settled around where they live now about the 13th century. They have traditionally been subordinate to Dai feudal lords. [Source: Tan Leshan, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia - Eurasia / China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

The Achang speak a Sino-Tibetan language with Dai, Burmese, Chinese and Jingpo influences. Some Achang practice Theravada Buddhism. Others worship ancestors and spirits and deities divided into good and evil. Most households have an altar used for making sacrifices. Many villages have a temple, where certain gods are enshrined and sacrificial rites are held. There are some similarities between the Achang and the Dai and Jingpo See Dai and Jingpo articles.

The Achang live mainly in southwest Yunnan Province in Longchuan and Lianghe Counties in Dehong Dai-Jingpo Autonomous Prefecture. There are also a small number of them scattered in Luxii, Yingjiang, Tengjiang, Yunlong and other counties in Yunnan. Most of them live mixed with other ethnic groups, namely the Dai and Han. In Myanmar there are about 2,000 Achang, locally called Maingtha. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences]

The Achang inhabit an area of hills, canyons and flatlands along the Yunnan-Myanmar border, where the soil is fertile, the climate mild, and the rainfall adequate. All of these are good conditions for the development of their agriculture. Achang people have been known for their rice producing skills since antiquity. The Achang area is situated on the southern tip of the Gaoligong Mountains. The area is crisscrossed by the Daying and Longchuan rivers and their numerous tributaries. The river valleys contain many plains, the Fusa and Lasa being the largest of them. Dense forests populated by deer, musk deer and bears cover the mountain slopes. Natural resources include coal, iron, copper, lead, mica and graphite. [Source: China.org]

Achang language belongs to the Burmese branch of the Tibetan-Burmese family of languages. It has three main dialects, named after the place where most of their speakers live: 1) Lianghe dialect; 2) Longchuan (Husa) dialect; and 3) Luxi dialect. Some scholars think that the speakers of the Luxi dialect migrated from Lianghe some generations ago, and consider that the two dialects (who have a 60 percent of correspondence of the most frequently used words with the same origin) are, in fact, only one dialect. As many Achang have long mixed with Han and Dai people, most Achangs can also speak Chinese and the Dai language. Their written language is Chinese.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Dai or the Tai and Their Architecture and Customs in South China” by Zhu Liangwen Amazon.com; “Where the Dai people Live” by An Chunyang Amazon.com; “Peoples of the Greater Mekong: the Ethnic Minorities” by Jim Goodman and Jaffee Yeow Fei Yee Amazon.com ; “The Yunnan Ethnic Groups and Their Cultures” by Yunnan University International Exchange Series Amazon.com; “Dai Lue-English Dictionary” by William J. Hanna Amazon.com; “Research on the Fertility Culture of the Dai Ethnic Group in China” by Shan Guo Amazon.com; “Educating Monks: Minority Buddhism on China’s Southwest Border” by Thomas A. Borchert and Mark Michael Rowe Amazon.com

Achang Population and Groups

The Achang are the 39th largest ethnic group and the 38th largest minority out of 55 in China. They numbered 39,555 in 2010 and made up less than 0.01 percent of the total population of China in 2010 according to the 2010 Chinese census. Achang population in China in the past: 33,954 in 2000 according to the 2000 Chinese census; 27,708 in 1990 according to the 1990 Chinese census. A total of 12032 were counted in 1964 and 31,490 were counted in 1982. More than 90 per cent of Achangs live in Longchuan, Lianghe and Luxi counties in the Dehong Dai-Jingpo Autonomous Prefecture in southwestern Yunnan Province. The rest live mostly in Longling County in the neighboring Baoshan Prefecture.[Sources: People’s Republic of China censuses, China.org, Wikipedia]

Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote in Ethnic China: The Achang live in Southwest China and Northeast Myanmar. In Myanmar there are only 2,000 Achang, locally called Maingtha. There are at least two ethnic groups included in the name Achang. Separated by more than 100 kilometers of mountain ranges they have many cultural and linguistic differences. There are also, some small groups called "Achang" whose identity is not yet clear. [Source: Ethnic China]

The two main groups are: The Achang of Lianghe County, who comprise 45 percent of the Achang's population. The Husa of Longchuan County who comprise 54 percent of their population. The Achangs from Husa think that they are the descendants of Chinese soldiers garrisoned in this area during the Ming Dynasty. In fact, in the decade of the fifties in the 20th Century, when China carried out the process of ethnic identification, they asked to be recognized as a differentiated ethnic entity, without success. They keep the ancestral tablets in their homes and believe in a kind of Theravada Buddhism with Taoist influences. *\

Between the small ethnics groups considered Achang, one of the less numerous are the Chintau or Xiandao. They are only 100 people. They live in two villages in Dehong Prefecture, Yingjiang County, Jiachang zone. One is Xiandao village in Mangmian, and the other is Le'e village in Manxiang. The religion and folkways of the Xiandao's Xiandao are similar to the Achang's. Men dress as the Jingpo people, women as the Dai. In Le'e village Xiandao people are mixed with the Han, from whom they have received many influences. But the Xiandao language is different to the Achang, and to their neighbors' languages. So, though they are officially considered Achang, more research is need, before determine their ethnic identity. *\

Achang History

where the Achang live

The Achang are regarded as one of the earliest ethnic groups in Yunnan Province. They were identified as "Echang" or "Achang" in ancient Chinese history books. Over the centuries there were several variations of the name pronounced the same but written differently in Chinese language. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the group was formally called the "Achang nationality" by the Chinese government. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities]

It is believed that the Achang are descendents of the Qiang tribes that 2,000 years ago inhabited the border region between Sichuan, Gansu and Sichuan provinces. There are numerous references to the frequent wars fought between the Chinese and the Qiang in the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.– A.D. 220). Wars and natural disasters forced some Qiang branches to move to the South. Members of one of these branches is thought to be the ancestors of the Achang. The migration took place over at least one hundred years and covered more than 2,000 kilometers before reaching their current situation in the southern confines of China. [Source: Ethnic China]

In the 8th and 9th centuries scholars think that the Achang were living among the Yue. Later on they are mentioned in the chronicles as one of the vassal peoples of the powerful Nanzhao Kingdom, and of the Dali Kingdom afterwards. According to the historical records from"General Geography of Yuan Dynasty" (1271-1368), the Achang have lived in what is now Dehong Dai and Jingpo Autonomous Prefectures and Tengchong county since before the Yuan Dynasty. According to records in 'General Information of Yunnan Province ' written during Emperor Zhengde's Reign in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), the Achang people were descendants of the Xunchuan people. In Tang Dynasty (618-907) the Xunchuan people, the records say, were under the control of the Nanzhao kingdom, and at that time they lived a very primitive life with no silk or cottons, and no kings or leaders. It is believed the descendants of the Xunchuan people gradually evolved into the Achang and Jingpo ethnic groups in the Yuan and Ming periods. [Source: Chinatravel.com]

During the Song dynasty (960-1279), travelers who visited Achang territory wrote a confederation of Achang tribes. Until the 16th century the Achang were largely associated with the Kachin (Jingpo). After there was a clear differentiation between the Achang and Kachin. During the Ming dynasty the Achang were governed under the tusi system of local chiefs, mainly Achang themselves, governing their people on behalf of the emperor. This system was effective until the end of the Qing dynasty (1911), and was preserved with few modifications during the Republic of China. *\

A few centuries ago, all of the land in the Achang region belonged to Dai feudal lords and hereditary Achang chiefs. According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: The Achang have traditionally been politically subordinate to the Han and Dai. Before 1949, Achang society was still at the chiefdom level of political development. The Achang, along with other ethnic peoples (the Dai, Han, Jingpo, and Lisu), formed separate multiethnic political units, each governed by a Dai feudal lord or a localized Han feudal lord. The hereditary feudal lord possessed paramount power of administration, adjudication, and supervision of military affairs in the area under his jurisdiction. The village was the basic unit of administration, governed by a village head who was usually elected by villagers and approved by the feudal lord. Several villages were governed by an officer who was appointed by the feudal lord. [Source: Tan Leshan, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia - Eurasia / China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

After the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, the Communist central government gave the Achang a reasonable amount of regional autonomy but exerted control in some areas and allowed the migration of Han settlers into Achang areas. James Stuart Olson wrote in "An Ethnohistorical dictionary of China”: "The central government become increasingly involved in the economic life of the Achang. State programs to resettle Han people throughout the country as a means of encouraging assimilation have bought tens of thousands of immigrants to western Yunnan Province. The newcomers have succeeded in taking control -through outright seizure, legal purchase, or government condemnation -of large portions of Achang land. After 1956, the Achang still engaged in agriculture were forced by law to sell their produce to the central government at a fixed price." The next 30 years saw a steady decrease in agricultural output, only reversed when early economic reforms began taking root in the early 1980s.

Achang Religion

The Achang are mostly Theravada Buddhists who retain there traditional animist beliefs to varying degrees. Achangs generally practice ancestor worship. Most Achangs on the Fusa plain, under strong influence of the Dai ethnic group, practice Theravada Buddhism. Achang of Lianhe worship the spirits of their ancestors and the spirits of nature, with the spirits of ancestors being particularly powerful, capable of bringing prosperity or misfortune to their descendants. Funerals take place on in auspicious days, without anything metallic on the body, since this can affect their reincarnation. People believe that Yama, the God of the Hells, allows the souls to return to the earth on the first day of the seventh lunar month. Those who die for infectious illness are cremated. [Source: Ethnic China *]

Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote in Ethnic China: “The different branches of the Achang people have religious beliefs with many common elements, as well as evident differences. 1) The Achang from Husa are Buddhist. They follow the Theravada school of Buddhism, the most popular in Southeast Asia. Due to their long contact with the Dai people they celebrate religious festivals characteristic of the Dai, such as the Water Splashing Festival. Intertwined in their Buddhist faith are numerous vestiges of their original religion and the original religion of the Dai, such as the cult to the God of the Village or Seman. *\

Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote in Ethnic China: “The different branches of the Achang people have religious beliefs with many common elements, as well as evident differences. 1) The Achang from Husa are Buddhist. They follow the Theravada school of Buddhism, the most popular in Southeast Asia. Due to their long contact with the Dai people they celebrate religious festivals characteristic of the Dai, such as the Water Splashing Festival. Intertwined in their Buddhist faith are numerous vestiges of their original religion and the original religion of the Dai, such as the cult to the God of the Village or Seman. *\

Each village has a Seman worhsipping site, which is established at at particularly big or leafy tree that the Achang think contains the god’s spirit. In front of the tree a stone is placed to mark it. Seman is worshipped at least twice a year; on the New Year's Day, to ask him a good harvest, and during the Harvest Festival, to thank him. Girls leaving the village to marry are expected to carry out a ceremony to honor Seman, offering a meal that is distributed among everyone. The Achang think that the Seman is able to protect the people of the village, their livestock and their crops. The ceremonies that honor Seman can be directed only by descendants of the founders of the village. Another vestige of the traditional religion of the Achang is the cult of Banqing, the God of the Sun, who the Achang believe has power to bring prosperity. Each family worships him next to their house at a shrine comprised of a bamboo tube stuck in the earth, whose upper end has a basket from which four smaller tubes of bamboo, protrude in the four cardinal directions. *\

The religion of the Achang of Luxi is similar to that of the Achang of Lianhe (See Below). They believe that people have three souls, but they only worship their ancestors for two generations, and think that the illnesses are caused by the spirits of the ancestors that bite people, whom they refer to as the Great Family or the Small Family. Among the spirits of nature they emphasize are the cult of Dimu, or the Mother of the Place, that it is generally worshipped under a great tree next to the village. Good spirits include the Spirits of the Hunt, of the Mountain and of Millet. Among the malicious ones are the Spirits of Death, of Hunger, of Fatigue, of Oppression, and of Sterility. *\

The Achang of Luxi have three types of priests or shamans: 1) The Motao, that expel the wicked spirits by reciting the scriptures; 2) The Buguishi, or fortune-tellers, consulted continually on multiple matters; 3) The Zhangzhai, that direct the ceremonies to honor the gods of the village. *\

Religion of the Achang of Lianhe

Achang of Lianhe worship the spirits of their ancestors and the spirits of nature, with the spirits of ancestors being particularly powerful, capable of bringing prosperity or misfortune to their descendants. The Achang believe that every person has three souls. At the moment of dying each one of the souls follows a different road. One stays in the tomb, another goes to the homemade altars, and the third heads off to meet with the King of the Spirits. After death, an important ceremony is carried out to send off souls in a proper manner. A shaman or Leibao is summoned. He spends one day and night reading scriptures to show the soul the route to travel. [Source: Ethnic China *]

In every house there is an altar to the ancestors similar to one that many Chinese houses have. Ceremonies are conducted here at least three times a year: On the first day of the lunar year, and on the first day of the seventh month to request a good harvest; and on the 15th day of the eighth lunar month, to offer thanks for the harvest. Some families carry out ceremonies for their ancestors every month or even every several weeks. The soul that is in the tomb is worshipped on the day of the Brilliant Purity (Qing Ming) according to the Chinese calendar. The Achang offer paper money to the soul with the King of the Spirits on the first day of the seventh lunar month, when it is believed that the doors of the sky open up and the spirits can return to earth. *\ Sometimes, the spirits of the ancestors display nasty behavior, and like to bite and harm people. These spirits are known as Spirit of the Great Family or of the Small Family, according to the size of the family. The Achang think that when a person is sick it is because of these spirits. So when that happens, they call a Leibao or shaman to expel them by reading sacred scriptures while a pig and a cow are sacrificed. Less harmful are the spirits of the girls that left the village to marry, but it is believed that if they have been poorly treated, after their death they may return to their home village and bite the people there. *\

Among the spirits of nature the Achang believe help people are: Pang or the God of the Wealth (in some villages he is represented as an old man); Guqi, a goddess that protects the warehouse of the grain; and the Spirits of the Earth, of the Mountains, of the Crops and that of the Hunt. These are sometimes worshipped in the same temple. Among the bad spirits are those of the Sun, the Moon, the Wolf, the Wild Mountain, Hunger and Fatigue. The most important is Meitou, who was opposed to the King of the Creation. Evil spirit can bring misfortune and illnesses. Each is believed to affect a different organ or part of the body. *\

Achangs generally bury their dead. In Buddhist areas, funerals are scheduled on holy days and follow the chanting of scripture by monks. One monk leads the funeral procession. As he walks, he holds a long strand of white cloth tied to the coffin, as if he were guiding the dead into the "Heavenly Kingdom." The coffin is to be carried above the heads of the close relatives of the dead, figuratively providing the deceased with a "bridge" to cross the river to the netherworld. The dead are buried without their metal ornaments; even the gold coatings on false teeth must be removed to make sure nothing will contaminate their reincarnation. Those who die of infectious diseases or childbirth are cremated. [Source: China.org |]

Achang Creation Myth: Zhepama and Zhemima

The most important myth for the Achang is that of Zhepama and Zhemima, which depicts the origin of the world and the first human beings. At the beginning of creation, in its primal state, the world was a mass of air in chaos. The first thing that appeared was light, and after it, darkness. From the interaction between light and darkness Zhepama, the Celestial Father, and Zhemima, the Earthly Mother, arose. In the void that existed after their creation, Zhepama, with the help of a magic whip, started the creation of the sky. Later he created the sun and the moon. He pulled up his breast (for that reason men don't have them) to make two high mountains, where he placed the sun and the moon. Between these two mountains he made a tree in such a way that the sun and the moon follow each other continuously. When you see the sun it is day time, if you see the moon, it is night time. Then he created the clouds, the stars and all that there is in the sky. [Source: Ethnic China *]

The most important myth for the Achang is that of Zhepama and Zhemima, which depicts the origin of the world and the first human beings. At the beginning of creation, in its primal state, the world was a mass of air in chaos. The first thing that appeared was light, and after it, darkness. From the interaction between light and darkness Zhepama, the Celestial Father, and Zhemima, the Earthly Mother, arose. In the void that existed after their creation, Zhepama, with the help of a magic whip, started the creation of the sky. Later he created the sun and the moon. He pulled up his breast (for that reason men don't have them) to make two high mountains, where he placed the sun and the moon. Between these two mountains he made a tree in such a way that the sun and the moon follow each other continuously. When you see the sun it is day time, if you see the moon, it is night time. Then he created the clouds, the stars and all that there is in the sky. [Source: Ethnic China *]

Next Zhemima knitted the earth. With the hair of her face and a lot of love, Zhemima created the earth of the east, of the south, of the west and of the north. Zhemima bled, and out her blood the seas that surround the earth were created. Then, from her flesh she made a great ship, on which rests the earth. But the earth was bigger than the sky, which could not cover it completely. Then Zhemima caused an earthquake and the mountains arose, and the sky was them adjusted perfectly to the earth. *\

Then Zhepama and Zhemima come to know each other, and out of the admiration that they felt for the work of each other arose love and the desire to create somebody to govern this world. After asking nature, they decided to marry. After nine married years Zhemima gave birth to a pumpkin seed that grew until it become an enormous tree which blossomed into a single flower. This flower took nine more years to produce a pumpkin that grew and grew, threatening to explode the world. Then Zhepama gave it a lash with his magic whip, making a hole in the pumpkin, from which nine children emerged. Zhepama and Zhemima taught the children the proper tasks of each sex. These nine children are the ancestors of all people. *\

One day a flood occurred. Zhepama asked Zhemima to sew up the world. She sewed stitchs for the east, the north and the west. To cover the south, Zhepama, with his generals, built a great wall and a door called the Southern Gate of the Heaven. Those living in the south asked Zhepama not to abandon them, and especially the Goddess of Salt, with whom he ended marrying. /*/

While Zhepama lived in the south, the Demon of Drought appeared in the world, spreading desolation everywhere. He placed a sun in the sky in such a way that it didn't move, burning everything. There was no more day and night, and everything was in disorder. Zhemima could not destroy the Demon of Drought; she could only wait for the return of Zhepama. But Zhepama, knowing nothing about what was happening in the north, continued living happily in the south. In view of the desperate situation of Zhemima a cat offered to leave in search of Zhepama. After a long journey the cat arrived in the south, and informed Zhepama of what was happening in the north. *\

After promising humanity that the peoples of the south and the north will remain in communication with each other, Zhepama left for the north. There, he challenged the Demon of Drought to a contest to measure their magic powers, agreeing that the winner is the master of the world. The Demon of Drought dried a peach tree with a fire ray, asking: "who is not afraid of death?" "The one who loves life doesn't fear death", Zhepama answered, while, launching a column of water, caused the tree to grow green again. Then they held a contest of dreams. The one who had a nightmare would be the loser. During two nights Zhepama had beautiful dreams, while the Demon of Drought dreamt nightmares of his defeat. He recognized his defeat. Zhepama offered to eat with the Demon of Drought, and Zhemima put poison in his food. The demon died. Zhepama cut him up and threw him into a well. *\

Achang Festivals

Most Achang Festivals—the Water-splashing Festival, New Year (or Spring Festival), the Jinwa (Buddha going into a temple), the Chuwa (Budda coming out of the temple), Torch Festival, Change Yellow Clothes, Watering Flowers Festival, Huijie Festival (Fair Street Festival)—are related with Buddhism. Besides their religious festivals the Achang in the Husa and Lasa regions also have several other important festivals, such as Going to the Market Day , Traditional Dancing Day, God — Worshipping Festival, Eating New Food Festival , Water Sprinkling Festival , Closing the Door Day, Opening the Door Day, most of which are quite similar to the festivals of the Dai ethnic group. In addition, the Achang people celebrate the Torch Festival, Wood Burning Festival, Worshipping the Ancestor Festival. Of all the festivals the Torch Festival and the Worshipping the Ancestor Festival are the two most popular and splendid ones with lots of various activities. The Achang New Year, celebrated at the same time of the Chinese New Year, during the first three days of the first lunar month.

Worshipping the Ancestor Festival is held every year in April according the local calender. It to commemorate the two ancestors of the Achang people — Zhepama and Zhema, for their good deeds and happiness they brought to their descendants. At this time the Achang people hold feasts, with dog meat and taros. Catching pythons is considered good luck. The Torch Festival is held every year on the 24th day aof the sixth lunar month in order to pray for a good harvest and no pests or natural disasters. On this day the Achang people kill pigs and oxes for sacrifice. And people will eat baked pork with rice noodles. In the evening they light the torches and walk around their villages. [Source: Chinatravel.com]

The Festival of Happiness in the Home takes place on the 4th day of the 5th lunar month. It is a festival to honor the heroes that shot their arrows against the suns in antiquity, when the world was scorched by nine suns, allowing the Achang to begin a life of prosperity. On this day, people from distant villages go to visit their relatives and friends, and together they pay homage to the heroes that opened to the Achang the doors of life. Festival of Worship of the Earth Mother takes place three times a year. On one horse day of February, and on 28th day of the fifth lunar month and 25th day of the sixth lunar month. It is a ceremony that honors the mythic Zhepama and Zhemima, who created the world and human beings, and who taught the Achang how to live on earth. [Source: Ethnic China]

The Achang Water Sprinkling Festival is viewed as a good time for young people to seek lovers, Girls and their families prepare eight delicious dishes of food to give young men. The numbers of the boys and girls must be equal for the party to begin. Young men try to take away the head of the chicken on the table during the dining without being detected, If they are caught by the girls, they are punished by drinking a cup of wine. If they are not caught, the girls have to drink a cup of wine instead. If an unlucky guy is detected just when he is doing the 'stealing' , he not only has to drink wines, but is also laughed at by the girls. \=/

Achang festivals are characterized by a lot of singing. Singing is an intrinsic part of many facets of Achang life. They sing while working, while courting, and during festivals. Many times they sing in duets. Dance, accompanied by music, is the main activity during many festivals. Their more famous dance is the Dance of the Elephant Drum, in which the dancers move backward and forward, to the right and to the left, following the rhythm of the music. They also dance the Lion's Dance, with Chinese influences; and the Dance of the Monkeys, imitating the movements of these animals. *\

Huijie Festival

The Huijie Festival is a traditional festival in the Husa and Lasa areas. In the past, it was usually held in the middle of the ninth Chinese lunar month and lasted about fifteen days. Now, the time has been changed to three days around the National Day on October 1st. Playing green dragon and white elephant is the most exciting and important entertainment of the holiday. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences ~]

A Green dragon and white elephant—symbols of good luck and happiness to Achangs— are made before the Huijie Festival. On the break of the day, young men take Husa long swords and beat their elephant-feet drums, while young girls wear beautiful and charming traditional clothes. The green dragon and the white elephant appear with a large crowd of people, accompanied by drumbeats and other music instruments. When they enter the square, the elder who presides over the festival declare the start of the Huijie Festival, and of a sudden all the drums, Mang Luos (gongs), and Bos (percussion instruments) begin to play. In the joyous music, the dragon and the white elephant start dancing—the green dragon shakes its head or tail, or makes cheerful laughing with its mouth open; the white elephant swings its long trunk, walks forward and backward, does a slipping walk, kneels down, or stands on its hind legs or forelimbs. The clumsiness and loveliness of the dancing animals arouse roars of laughter among the audience. Then, young men and girls start dancing around the green dragon and the white elephant. Their bodies move like waves when they are jumping and moving together. ~

The green dragon and white elephant are made with a wood frame and paper covering, with cloth used to make the dragon head and tail and elephant trunk. When performing, there are men in the bodies of the dragon and the elephant. Some men are responsible for carrying the dragon or the elephant, and some for moving head and tail of the dragon and the elephant’s trunk. Thus, the green dragon can raise its head, open or close its mouth, and swing its tail, and the white elephant can swing its trunk. ~

Achang Family and Kin Groups

Descent among the Achang is patrilineal. Members of a patrilineal descent groups are can be distributed over either a village or several villages, but all of the members trace their relationship through males to a common ancestor. In Lianghe County, there is a patriarchal organization that prevails in local Achang communities. The organization has its own rules and a patriarch who is elected from among the senior males. Disputes among members are often worked out by this organization. Han people sometimes marry into the patriarchal organizations and are given a common surname.[Source: Tan Leshan, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia - Eurasia / China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

Achang kin terms basically follow the Eskimo system. This joint family system makes no distinction between patrilineal and matrilineal relatives; instead, it focuses on differences in kinship distance (the closer the relative is, the more distinctions are made). The system emphasizes the nuclear family, identifying directly only the mother, father, brother, and sister. All other relatives are grouped together into categories. One exception is that there is only one kin term for each of the following pairs: brother and male cousin; sister and female cousin; son and nephew; and daughter and niece.

A patriarchal family unit generally includes two or three generations. A young man, if not the youngest son of his parents, usually establishes a place of residence apart from his parents when he marries. The youngest son lives with the parents and inherits either the parents' house and property or the responsibility of taking care of the parents.

Achang Love and Marriage Customs

Marriages tend to be arranged. There are no restrictions on partners as long as they are outside the patrilineal clan. In the old days bride kidnaping was practiced. Women receive a dowry but do not inherit wealth unless they have no brothers. The youngest son usually lives with the parents and inherits the family property.

Marriages between the people sharing the same family names are not allowed. Traditionally, the son-in-law has come to live with the girl's family and the man takes the girl's family name after going to live there. According to the Chinese government: The basic unit of the Achang society is the patriarchal, monogamous family. Young men and women are free to choose their spouses. Courting rituals are quite specific. When dusk falls, young men go to bamboo groves near the homes of the young women they desire and play the sheng to win their favor. In some places, groups of young men and women gather around a bonfire, where couples flirt by singing alternate verses. This can go on until dawn. Before 1949, marriages were arranged by parents, which often led to forced marriage and misery for unlucky young lovers. The Achangs have a strict incest taboo: people with the same surname do not marry each other. But intermarriage with Hans and Dais has always been permitted. [Source: China.org]

In Achang villages, after dusk, young men and women meet to sing. This is how they get to know each other and find possible partners. Such song gatherings sometimes last until dawn. Once a courtship is formalized, it is normal for the lovers to spend a lot of time in the girl's home. When the boy goes to visit the girl, her family retires discreetly, and the two lovers remain together, singing for long periods of time. But they don't have sexual relations; if they do, they are censored and punished. To have sexual relations before marriage is frowned upon. Children born out of wedlock bring social discrimination to both the mother and child. Many unmarried women who get pregnant discreetly get an abortion. [Source: Ethnic China *]

Usually the parents arrange the marriage, with the help of a matchmaker. Although they sometimes act in accordance with their children’s wishes, young people often do not have a say in the choice of their marriage partners. The paternal uncle plays an important role in Achang weddings and marriages. Sometimes cross cousin marriages are preferred. Other times, a marriage is arranged as an exchange between two families, often in order to avoid excessive wedding expenses. In old days, sometimes a considerable payment was made to the bride's parents as the loss of a daughter was viewed as a lost worker.

When two young people are deeply in love, but their families don't agree to the marriage, they can carry out a "marriage by abduction" or "kidnapping marriage". Marriage by abduction allows couples to escape from unwanted arranged marriages. Once carried out, the "marriage by abduction" is usually accepted by both families, although the gifts that the bridegroom gives are usually twice the usual amount. The Achang also practice the transfer of widows. This means that the widow of an older brother can marry a younger one.

Achang Wedding

woman's brocade dress

An Achang wedding can lasts for three days. One of the highlights is when the bride and groom propose toasts to each guest one by one, and the guests put some coins into their cup after finishing it. The Achang wedding day rituals begins when the couple arrives at dawn at the groom’s house. Two best men accompanying the groom with umbrellas to meet the bride is one of the special and interesting features of an Achang marriage. On the wedding day, the groom leads a group of relatives and friends to the bride's home to meet her. When they get into her courtyard, sisters of the bride splash water towards the groom to make fun of him or to test him. The well-prepared “guards"—the two best men— open their umbrellas to shield the groom on both sides from the splashing water. The three then proceed forward while trying to avoid being splashed. the water. If the groom gets wet, the splashing girls feel they have won and laugh and tease the young men; if the groom and his partners move with agility and the groom remains largely dry, they wink and smile at the girls to show that they have won. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

About this custom, the Achangs say: "Water had once brought in a misfortune; now let the umbrellas save the groom." According to the legend the custom is derived from a tragic love story that occurred long ago. A young girl married her lover secretly to resist an arranged marriage. Seeing no hope of breaking them up, her angry brothers poured cold water on the groom on the wedding day when he came to meet the bride. The cold water killed the groom. In despair, the girl committed suicide by hanging. In order to remember this tragedy as a lesson and also in memory of the brave girl, people added this custom to wedding ceremonies. The original intent has largely been forgotten. No it is a ritual to create a joyous atmosphere.

Another custom of Achang wedding ceremonies that is even more joyful and interesting occurs at the wedding feast, when sisters of the bride seize every opportunity to blacken the groom's face with pan soot. Then, they take two long bamboos with leaves and give them to the groom. The groom has to use them as chopsticks to hold a piece of meat. The long and clumsy bamboos are hard to control; what is worse is that someone always touches the tops of them from behind, which makes the task even more difficult. Seeing the groom having such a hard time, makes everyone roar with laughter. ~

Achang Houses and Life

The Achang tend live in villages set at the foot of mountains on small plains. Their villages are often made up of families related along patrilineal lines, often with some Han, Dai or Hui living there. Many speak Dai and Chinese and have intermarried with Han and Dai. Achang descent is patrilineal. Often members of a village or a group of villagers can trace their relationship back to a common ancestor. Villages are headed by a singles chief selected by a council of elders, which also settles disputes.

The Achang grow wetland rice, their primary source of food, during the rainy season on terraced fields. Many families also crow cash crops such as such as sugar cane, tobacco and food oil crops. Achang blacksmith are known for their skill. They produces swords and knives and agriculture tools such as plows and sickles. Achang men sometimes wear swords with silver ornaments. Women are considered skilled weavers.

Achang villages are generally orderly and well organized. They are connected by gravel paths or roads paved with stone slabs. The Achang have traditionally lived in courtyard houses of brick or stone with wood beam supports of two-storey square houses made of wood or bricks, with the upper floor serving as the people's living area, and the lower one to keep animals and agricultural tools.[Source: Ethnic China *]

The bedrooms in Achang houses are located on either side of the main room. The bedroom of the old people is on the right side, while others' are on the left side. Male seniors are not allowed to enter the married juniors' bedrooms. Unmarried men can live in the wing rooms or upstairs of the wing rooms. Women should not live upstairs. When men are downstairs, women should not go upstairs. [Source: Chinatravel.com]

It is believed that the Achang originally lived in a matriarchy, but many centuries ago their society changed to a patriarchal one, with clans comprised of several families. The Achang are famous blacksmiths. It is said that their skills date back the 14th century, in the region of Husa, when blacksmiths of the Chinese army garrisoned in that area, taught to them. In every village the blacksmiths tradition have been passed from father to son from one generation to another. Their knives and tools are exported to many regions. *\

Achang Food and Betel Nut

Achang swords

For food, Achangs eat rice as their staple and prefer sour dishes. Although the habit is disappearing, young men and women still enjoy chewing betel nut, which blackens their teeth. In the old days the Achang used to say “black teeth means beautiful.” Beef and pork are the favored meats. The Achang like to make boiled pork rice noodles using pork from pigs that have been roasted on a fire of wheat straws or rice straws until the skin of the pig becomes golden brown. After that the pork is cut into small pieces and mixed with vinegar, garlic, pepper and at last eaten with rice noodles. Raising fish in the rice fields is another major protein source. Fish is usually fried in hot oil and then steamed with sour peppers. This is sometimes called sour and hot after — harvest fish, as they put the fish fries into the rice field when planting the rice, and get the fish out after harvest. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

The Achang like rice filum made from small pieces of rice as well as rice noodles . The rice filum is easy to make: just put it into boiled water for a few minutes and then take it out and mix it with some spices or pork and chicken. Rice noddles are often eaten cold. The Achang also like to put a spoon of hot soya flour into the rice noodles together with hot pepper, garlic , ginger and monosodium glutamate. \=/

The Achang are fond of taro. According to one Achang legend in ancient times whenever there was good harvest, the Achang ate taro and killed dogs. Staple dishes including tofu, bean powder dishes, cold noodles with peas, cold celery powders, cold meat, pickles and "Hand Making Rice Noodles". Salted preserved vegetables, beancurds , and soy sauce are made at home and eaten all through the year and are consumed at almost every meal. Wine is a very popular beverage. Achang women always make sweet wines from sticky rice. Old people like homemade white spirits made from distillation and preserved in a big earthen jar. It is consumed at festivals and offered to guests. \=/

When making sticky rice, the Achang first wash the rice and then put it in clean water for about half a day. After that put the rice into a rice pot and steam it before eatting it. Sticky rice cakes are very soft and tender. You can also serve the cakes on a banana leaf or fry it or bake it, steam it or braise it. Hand Making Rice Noodles is a popular food among the Achang in the Husa region of Longchuan County. The noodles are made from local high quality rice and mixed with 'fire burned pork ', pig liver, pig brains, pig intestines, peanuts, sesame, garlic, pepper, coriander, salt, monosodium glutamate , soy powders and vinegar. When eating, grab the noodles in your hands, mix them with condiments and pop them in your mouth. \=/

Achang Customs and Taboos

The Achang people are very hospitable. When a guest visits the host is expected to provide good tea or wines and let the guest sit in best place. If the guest is younger or junior, he should not refuse to sit at a side seat or lower seat. The Achang insist that their guest eat and drink in large quantities and it can be rude to refuse. Even if the guest is full, he should stretch out his bowl with both hands and stand up, and accept the food graciously. The host may also show his friendship and hospitality by singing a folk song. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

Some taboos of the Achang 1) After marrying, siblings don't enter each other bedrooms. 2) The first day of the year no creatures should be killed, because it is considered inauspicious. 3) Women cannot be in the upper floors if men are downstairs. 4) Men should not walk where the women hang their skirts. 5) No man or other family should enter the house of a new mother for the first seven days after childbirth, 6) Women can not step over or walk on farm tools or other instruments, because this, it is said, diminishes her capacity to do farm work. 7) Women cannot sit down astride the house door, because it is considered inauspicious. 8) Strangers cannot move the tablets of the ancestors in a house. 9) After a baby is born, men from other families are not allowed to enter the courtyard of the mother’s house for seven days. 10) When an engagement or oath is cancelled, the photos or hairs taken from the other person should be given back rather than burn them. Otherwise it is believed that after the photos or the hair is burned, the person will be very sick or even get mad.

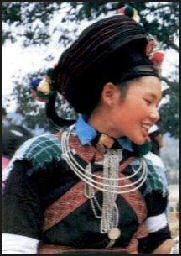

Achang Clothes

Achang brocade

Achang traditional clothes are simple, austere, and beautiful and vary from one place to other. Men like to wear a machete or Husa knife. Women dress in a different ways depending on whether they are single or married. At festival the married ones like to wear big turbans, sometimes adorned with silver. When you get into an Achang village, you will often see both young men and young women wearing flowers as head as ornaments. These are not only regarded as beautiful, but also seen as a symbol of their integrity and chastity. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

Most traditionally-dressed Achang men wear blue, white or black jackets buttoned down the front, and black trousers with short and broad bottoms. On the Lasa plain many men wear jackets with buttons toward the left side. Unmarried men wrap their heads with white cloth, while married men have indigo cloths. Some middle-aged and old men like wearing felt hats. When young or middle-age men wrap their heads they let the fringy part of cloth droop down over the head. When men go to market or to a festival party, they like to carry a "tongpa"(satchel) and a Husa knife or machete. ~

Women's Costumes depend on how old they are, where they live and whether they are married. In general married women wear skirts and jackets with tight sleeves and wrap their heads with black or blue cloth that may go as high as three decimeters. Unmarried women wear trousers and tie their pigtails on top of their heads. On ordinary days, unmarried girls usually wear jackets of various colors, which are either buttoned on one side or in front. They also wear aprons and have their heads wrapped with black cloth. Girls in the Lianghe area like wearing straight skirts. Married women usually wear black blue jackets buttoned down front and straight skirts, and leg wrappings. They are fond of wearing tall black head wrappings in the shape of a pointed cap and with four or five embroidered colorful balls. Achang women like to wear silver objects on festive occasions. On special occasions or when going to market or to visit someone as a guest, or on festival days, they wear elaborate clothes and various ornaments such as large earrings, decorated bracelets and silver necklaces, and silver chains on the bosom buttons and their waists.

Achang Culture

Achangs treasure their oral culture of ballads, stories and folk tales.Singing alternating duets is a favorite evening recreation of young men and women. Musical instruments used by Achangs include the bamboo qin (a stringed plucked instrument), the bamboo flute, the gourd-shaped sheng (a wind instrument), the sanxian (a three-stringed plucked instrument), the elephant-leg drum and the gong. The "Elephant Foot Drum Dance" and "Monkey Dance" are the two most popular types of dance. Folk sports including swinging on swings, horse races, shooting, and performances of Achang knife fighting and martial arts. [Source: China.org]

The Achang have very rich and colorful oral literary tradition that includes ballads, stories, legends and epic poems such as '”Zhepama and Zhemima,” " Caozha", and "The Blacksmith Fights the Dragon King". Among the the popular folk stories are "Grain and Millet", "Cousins", and "Hipbone" and animal stories like "The Deer and the Leopard Exchange Their Jobs" and "The Old Bear Tears His Cheek Skin". [Source: Chinatravel.com\=/]

Antiphonal singing (singing alternating duets) a a popular activity among young men and women. It can be divided into three kinds: 1) "Xiangleji", which refers to the folk songs sung by the young men and women outdoors, in which singers improvise the songs according to their feelings using imagery of mountains, water, clouds , trees other natural things; 2) ' Xiangzuo ', sung by young men and women when they are alone on a date in the woods; and "Xiangmole" , is also a kind of songs sung between dating young men and women. \=/

Handicrafts include embroidery, lacquering, dyeing, weaving, engraving and silverware making and are known for their elaborate patterns and detail. Achang engraving is extraordinary and can best be seen on furniture, buildings and Buddhist shrines, on which workers have etched vivid forms of animals and plants. |

Achang Musical Instrument of Love

Musical instruments of Achang include the gourd-shaped flute (a wind instrument), March flute (also a wind instrument), copper-rimmed stringed instrument, sanxian (a three-stringed instrument), Xiangjiao drum (a drum in the shape of elephant foot) and the mang luo (gong). Arguably the most important one is the gourd-shaped flute made of three bamboo tubes connected with a bottle gourd. Having seven tones, it is loud and clear, and is often played in the daytime. The gourd-shaped flute and the March flute are often used by young men to express their love to young women. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities]

Every year, at festivals, during the farming-free season, and after daily chores are finished, young men take March vertical flutes in their collars behind their necks or on their sides wherever they go. They like playing mellifluous melodies when they across girls they admire. This may occur near a village or on a road to the market. Through his music, a young man may ask for a girl her for a favor, to stop what she is doing and talk to him or simply ask he what her name is. If she doesn’t have a boyfriend and likes him, she may respond positively to his advances, singing "If you are sincere, you should accompany me all the way to the village rather than half the way." The young man then plays his flute and sings folk songs to accompany the girl home. That is often how a story of love starts.

When the sun is setting, a young man courting a girl cleans himself and dresses in his best clothes and goes quietly to the house of his beloved. He plays his gourd-shaped flute to ask her out. Hearing the gentle and familiar melody, the girl dress ups and goes to meet her boyfriend. If it is the youth's first visit, he may be invited inside to sit near the hearth by the girl's sister in-law or mother. Then the family members peel away and the young couple sits together and sing love songs or talk, often until roosters heralds the break of day.

Famous "Husa Knife"

The handicraft industry of the Achangs is well developed. They are especially adept at forging and making knives. The "Husa knife", which is also known as the "Achang knife", gets its name because it is made mainly in the Husa and Lasa areas of Longchuan County where many Achangs live. This sort of knife is "well-forged and elaborately made, and very sharp, tensile and durable." Sheaths made of wood, leather, silver and other materials are extremely exquisite, too. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

Achang knives vary in length and shape. There are more than ten sorts of knives. For instance, there are working knives, knives for daily use, long swords for hunting and self-protection, and daggers for butchering domestic animals, and the like. Achangs also make knives for other nationalities, such as Tibetan knives and Jingpo knives. Due to their exquisite smithcraft, Achang knives are not only cherished as a legacy by Achangs, but are also favored by other neighboring ethnic groups like the Han, Dai, Jingpo, Tibetans, and Bai. ~

The Achang have an over-six-hundred-year history of making knives and other cutting tools. Tradition says that a Chinese army stationed in the Husa and Lasa areas in the Ming dynasty contained craftsmen that were skilled at blacksmithing and making weapons. These men married with the local people and gradually merged into them. The Achang inherited and developed the Ming army's art of smelting and forging, and came to produce many knives with unique characteristics. Over time, their techniques became more exquisite. Craftsmen are typically skilled at making specific kinds of products and every village has its own products. The whole Husa area is filled with knife factories and a workshops. Laifu village is known for its long black knives and Hugang knives (decorated steel knives); Mangdong village makes broadswords and small pointed knives; and Lajie village is famous for saw-toothed sickles, Xin Village for carry-on-back knives, and Mangsuo village for sheaths. ~

Husa knives is very durable for two reasons: first, it is made of well-chosen materials; second, the Achangs have very fine skills in quenching and hardening steel; in addition, it is carefully and beautifully ground. Because of these virtues, knives made by Achangs can be very sharp with just a little grinding. Some old craftsmen can even make knives that are both firm and flexible, of which some can even be curled up and straightened out. For example, a long sword when not in use can be curled around the waist like a girdle, and when needed it will straight itself out. Their handicraft is unique and admirable.

Achang knife

Achang Economic Activity and Agriculture

The Achang are primarily farmers, with wet-rice cultivation being their main agricultural activity. Traditional wet rice agriculture has been adapted to local climatic conditions. After the monsoon brings enough rain sowing begins. When the rainy season is over, the rice is mature enough to harvest. After harvest, the rice is sorted into two portions: one set aside for use by the household in the following year, and one for payment of hired labor or land rent in the past. In addition to rice, the Achang also grow cash crops, such as sugarcane and oil crops in Lianghe and Luxi and tobacco in the Fusa plain area. [Source: Tan Leshan, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia - Eurasia / China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

Achang blacksmiths in the Fusa and Lasa regions are famous for making various types of knives and swords. Some say that the forging technique used by the Achang came from the weapon smiths of Chinese troops stationed in the Fusa region in the fourteenth century. Since then, the manufacturing of ironware has a mainstay of the Achang economy. A workshop has traditionally been owned by several households. Often workshops in one village specialize in producing a specific of product — a sword, sickle, dagger, plowshare, chopper, hoe or horseshoe. Manufacturing of ironware was often seasonal, with ironworkers doing much of their work during agricultural down times. In recent decades, machines have become more commonplace. Silversmithing, carving, textile production and decoration for temples and other buildings are all developed industries. |~|

Before the Communists took over China in 1949, the ownership of most lands had been passed on from feudal owners to individual peasant families although everyone who owned land had to pay tax to them, as a token recognition of the feudal lords' continuing ownership of all lands. As a result of the private ownership of land, tenancy and buying and selling of land between peasants became frequent. The government established the collective ownership of land in 1956 but transferred landownership to the People's Commune in 1969. In 1982, the authorities redivided the lands among the resident households.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Map: Joshua Project

Text Sources: 1) "Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China", edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company; 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China ; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2022