SHUI MINORITY

The Shui are an ethnic group that lives along the Long and Duliu Rivers in Sandu, Limbo, Dushan and Duyun in southern Guizhou Province. A small number live in the northwestern part of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. Also known as the Sui, they are regarded as descendants of a branch of the ancient Baiyie tribe.

The Shui speak their own Sino-Tibetan language, which is similar to Zhuang and Dong. They have their own written language that uses a unique system of pictographs and is still in use today, mostly for ceremonial purposes. For the most part they use written Chinese in their daily lives. The Shui language belongs to the Shui language branch in the Chuang-Tong group in Sino-Tibetan family of languages. Ancestors of the Suis created their own character called "Shui character" that resembled the Oracle Bones inscriptions found on ancient Chinese bones, tortoise shells and bronze objects. “Shui character” has around 400 character-words and has traditionally been used mostly in shamanist activities. Some of their words are pictographs, while others resemble Chinese characters written upside down. It's unusual for an ethnic group with such a small population to have their own writing system, which can be used to record dates, directions and in fortunetelling.

The Shui live mainly in southern Guizhou Province in Sadu Shui Autonomous County, Libo, Duyun, Dushan counties in the Southern Guizhou Bouyei and Miao Autonomous Prefecture, and Kaili, Liping, Rongjiang and Congjiang counties in the Southeastern Miao and Dong Autonomous Prefecture. Some Shuis have their homes in the northwestern part of the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences ~]

Many Shui live among the Miao and Dong ethnic group. Their home territory is in southern Guizhou Province to the south of the Miaoling mountain range at the upper reaches of the Duliu River (Duliujiang) and the Dragon River (Longjiang). Here, clear water streams and rivers meander across plains and rolling land interspersed with vast expanses of forests. The area abounds with fish and rice. Wheat, rape, ramie are also grown besides a great variety of citrus and other fruits. The forests are a source of timber and medicinal herbs. The Duliu and other rivers teem with fish. Shui folk songs describe their homeland "as beautiful as peacock's tail". The Suis are mostly rice farmers. They are famous for their traditional "Qiuqiansa" ("Nine-footpath wine") wine and are engaged in forestry and raising fish, flowers and fruit. [Source: China.org | ~]

Shui are the 25th largest ethnic group and the 24th largest minority out of 55 in China. They numbered 411,847 in 2010 and made up 0.03 percent of the total population of China in 2010 according to the 2010 Chinese census. Shui populations in China in the past: 407,000 in 2000 according to the 2000 Chinese census; 345,993 in 1990 according to the 1990 Chinese census. A total of 133,566 were counted in 1953; 156,099 were counted in 1964; and 300,690 (0.03 percent of China’s population) were, in 1982. [Sources: People’s Republic of China censuses, Wikipedia]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: : “Rainbow Across Rivers and Lakes: The Shuis” by Zhou Hong, Yunnan Education Publishing House, China, 1995 Amazon.com; “Duan Festival of Shui Ethnic Group” by Yan Xiangjun and Liu Xiaoyu Amazon.com; “Embroidered Identities: Ornately Decorated Textiles and Accessories of Chinese Ethnic Minorities” by Mei-yin Lee, Florian Knothe Amazon.com “Guizhou Batik” by Wan Zhixian and Ma Zhenggrong Amazon.com; “Writing with Thread Traditional Textiles of Southwest Chinese Minorities” by University of Hawaii Art Gallery Amazon.com

Early Shui History

The ancestors of the Shui people are believed to have come from one branch of the Luoyue people and one branch of the Lingnan "Baiyue" people, one of the early tribes that lived along China's southeastern coast before the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-A.D. 24). The ancient Baiyue tribes are believed to be the ancestors of several ethnic groups now living in Guangdong and Guangxi, including the Zhuang, Shui, Miao, Yao, Yi and Dong. The Shui adopted their present name at the end of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). The name of Shui was fixed after new China was founded in 1949. In Chinese "shui"means "water" therefore, "Shui People" refers to people living along the waterside. The "Shui People" gained this name because they mainly dwell along rivers and streams, and their living customs, worship, and folklore revolves around water.

Since the Tang Dynasty (618-907), the Shui people have dwelt in the upper stream of Longjiang and Duliu Rivers, which was called "Fushui Prefecture" at that time. Due to war and pressure from other ethnic groups and oppression from the rulers, some people relocated from Red River to the middle stream of the Yellow River in Yunnan and Guizhou provinces. In the Tang and Song Dynasties they and the minority nationalities of the Zhuang and Dong branch were called "Liao" all together. In the Northern Song Dynasty, a "Zhou (an administrative division in former times) Appeasing the Suis" was set up in the Shui region. The Suis were often called "Shuimiaojia" or "Shiujia". [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, Chinese Academy of Sciences]

In the Song Dynasty (960-1279) villages were formed and rice growing began. By the end of the Song, the Shuis had entered the early stage of feudalism. The nobles bearing the surname of Meng initiated in the upper reaches of the Longjiang River a feudal system which bore the distinctive vestiges of the communal village. During the Yuan (1206-1368) and Ming (1368-1644) dynasties, a large number of Han People immigrated to or guarded Huguang Province, which was partitioned in the Qing Dynasty (1616-1911) into Hubei and Hunan, and stayed there and intermarried with Shui People. Because of their close proximity, these two groups melded together. [Source: Chinatravel.com]

Yuan rulers (1271-1368) established local governments at the prefectural level in an attempt to appease the ethnic groups. The Ming period witnessed a marked economic growth in Shui communities. The introduction of improved farm tools made it possible for farmers to open up paddy fields on flatland and terraced fields on mountain slopes. The primitive "slash and burn" farming gave way to more advanced agriculture characterized by the use of irrigation and draught animals. As a result, grain output increased remarkably. [Source: China.org |]

By the Ming dynasty (thirteenth and fourteenth centuries) many Shui had switched to wet-rice farming though others continued dry-field slash-and-burn agriculture. The Ming imperial court followed the preceding dynasty's practice of appointing hereditary Shui headmen. Under this system, the Shuis had to pay taxes to and do corvee for these court-appointed headmen as well as for the imperial court. During the two centuries between 1640 and 1840 the Shui economy continued to develop. Farm production registered a marked increase, with per hectare yield of rice on flatland reaching 2,250 kilograms. Some quit farming and became handicraftsmen. |

Yue (Baiyue) People See DONG MINORITY AND THEIR HISTORY AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com

Later Shui History and Development

According to the modern Chinese government: “In Chinese modern history, the Suis composed a brilliant chapter. In December 1855, Pan Xinjian led the Shui people to rise up, and put forward a very resounding slogan: "We won't deliver tax grain and pay tax, and we'll overthrow the Qing Dynasty and enjoy peace." They fought for 16 years, and were involved in the Taiping Uprising. In 1909, Wuchaojun led the Suis, Bouyeis and Mioas to rise up and advance the slogan of "wiping out foreign invaders and promoting Hans". They fought against invaders, imperialism, and feudalism, and exerted important influence all over the country. During the New Democratic Revolution, an outstanding son of the Suis — Deng Enming was the only minority nationality in the representatives of the First People's Congress of the Communist Party of China. During the War of Resistance against Japan and the Liberation War, the Shui people took part in fight actively which was led by local underground organizations of the Communist Party of China.” [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Chinese Academy of Sciences]

Sui-Kam Autonomous Prefectures and Counties

“After the Revolution of 1911, national capitalism gained some ground in the area. In what is now the Sandu Shui Autonomous County, iron mines and plants processing iron, mercury and antimony were set up, but later they were either taken over by Kuomintang monopolist capital or went bankrupt. The comprador capitalists plundered the rich natural resources, while big landowners annexed large areas of farmland. Ruthless exploitation through usury, hired labor and high land rent robbed farmers of 60 to 70 per cent of their crops, thus ruining a great many farmers.” |

“During the land reform in the early 50s, full respect for Shui customs was emphasized and public land was reserved for festive horseracing and dancing. In 1957 the Sandu Shui Autonomous County was established. Formerly only 13 per cent of the arable land was irrigated. Now thousands of water conservancy facilities have been built to bring most arable land under irrigation. Abundant mineral resources have been found and mined. Today local industries include chemical fertilizer, coalmining, farm machinery, sulfur, casting, sugar refining, winemaking and ceramics. Handicraft industries such as ironwork, masonry, silver jewelry, carpentry, textiles, papermaking, bamboo articles have also developed. [Source: China.org |]

“In the past, transportation was very difficult in this mountainous area, with only one 17-km highway traversing the county. Now all the seven districts in the county are connected by highways or waterways, and many towns and factories have bus services. The Hunan-Guizhou and Guizhou-Guangxi railways have further facilitated the interflow of commodities between the Shui community and other areas and strengthened ties between the Shui and other ethnic groups. |

“Before 1949 there were few schools in the area. By 1981, apart from 10 secondary schools and 145 primary schools with a total enrolment of 27,700, there was one ethnic minority school and one ethnic minority teachers' school. Officials of the Shui people now number over 1,000, or over 30 per cent of the county's total administrative staff. In the past malaria was rampant in the area with an 80 per cent incidence rate, but the only medical facility was a small hospital with three medical workers. After 1949 a large number of clinics and hospitals were set up. Thanks to the persistent efforts in the past years, malaria has been brought under control.” |

Religion of the Shui

Some Shui are Catholics. Most worship a pantheon of gods; sacrifice animals to appease spirits and seek the help of shaman to cure sicknesses. “Gaduo” are spirit traps placed on the slopes of mountains by Shui lovers to pray for a beautiful future. Shui prayers focus around nature, their ancestors, and totems. Evil spirits are highly respected. Even now, there are more than 300 named evil spirits and more than 400 that have lost their names. Shaman have traditionally been employed to say prayers and reside over animal sacrifices directed at evil spirits when someone falls ill or dies or when something bad happens. Catholicism arrived in the area in the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) but won very few converts. The Shui have a complex traditional religious system that revolves around a world filled with spirits. They believe all objects have their own spirit. Important activities and events, such as marriage, misfortunes, illnesses or death, are thought to influenced by spirits. Rites and other religious activities in this complex spiritual world are carried out by sorcerers or more powerful shamans, who generally sing appropriate words rites and sacrifice animals to held them communicate with the spirit world. [Source: Ethnic China *]

Shui spirits are divided into three types: protective, kind and wicked. The protective and kind spirits are worshiped with proper ceremonies that enlist their help protecting people, mostly on the village level. Wicked spirits are mainly dealt with exorcism rituals and protective ceremonies that either cast them out if they have caused harm and keep them away. The principal Shui gods are: 1) The God of the Fields, responsible for the crops and survival of the persons, honored with ceremonies at the time of sowing and harvesting; 2) The God of the Door, whose task is to protect the family; and 3) The Lady Goddess, in charge of protecting children. *\

The Book of the Shui is very important for Shui religious ceremonies. It consists of a White Book for the good things, and a Black Book for the bad ones. Most of the book is related with the exploration of the calendar and the way of chose the auspicious days for various activities. Sorcerers and shamans usually inherit their callings from fathers or uncles. Generally they work as farmers or other normal jobs while undergoing training and practicing shamanism. *\

The Shui believe that after the death the body decomposes but the soul can remain in the world as a ghost. It is necessary to carry out appropriate funeral rites to avoid this from happening. Their funerals are important and surprisingly festive occasions. While livestock is sacrificed in honor of the deceased's spirit, people sing, dance and perform local operas. According to the Chinese government, “Shui funerals used to be extremely elaborate. Livestock were killed as sacrificial offerings to the dead. Singing, dancing and performance of local operas went on and on until an auspicious day was found to bury the dead. Such wasteful funerals have been simplified in the post-1949 years.”

Shui Festivals

The Suis have their own lunar calendar. It differs from the Chinese lunar calendar in that the eighth lunar month marks the end of a year and the ninth month marks the beginning of a new year. According to the record of "Shui Letter", a year is divided into twelve months and four seasons (spring, summer, autumn, and winter). Before the festivals, you can hear rataplan, the bang of the drum, all over the villages. The biggest Sui festival is the "duan" holiday which is celebrated with great pomp after the autumn harvest at the beginning of the 11th lunar month. Garbed in their colorful costumes, the Shuis gather in their village to watch horse races and plays, and to feast for days on end. [Source: China.org]

The two other important Shui festivals of the Shui people are the Dragon Memorial Ceremony on the third day of the third lunar month and the Mountain and Forest Memorial Ceremony on the 6th and 24th of the 6th lunar month. At these festivals, Shui dance to rhythm of bronze drums and the music of Chinese wind pipe, entertaining guests with a five-color meals and distilled spirits and rum. |

The Duan Festival is the grandest in the year for Suis. It is calculated according to the Shui Book and Shui calendar, which divides a year into twelve months and four seasons, but it takes the lunar ninth month as the beginning of the year and the lunar eighth month as the end of a year and uses the twelve earthly branches to designate days. The Duan Festival last from the last ten-day period of the twelfth month to the second month next year in Shui calendar (that is the last ten-day period of the eighth month to the first ten-day period of the tenth month in lunar year). People in different places celebrate the festival at different times in turn according to the tradition that every pig day (called "Hai" day in Chinese) is one of the twelve earthly branches). The Duan Festival is also called the "Gua Festival". The Shui call it "borrowing Duan". [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China ~]

It is a Shui tradition that "if you spend the Duan Festival, you can't spend the Mao (one of the twelve earthly branches, which means rabbit) Festival, and vise versa". In addition, the order in which different places hold the feasts should not be reversed or mixed. A relatively consistent legend about the origin of the custom is: in ancient times, the forefather of the Suis-Gongdeng had two sons. The older one was assigned to live in the upper Neiwatao area, the younger one was assigned to live in the Jiuqian area below. They agreed to meet every year at their father's home for a feast after the harvest. Later the brothers felt that the distances were too far, and it was not convenient for them to come and go to their father’s house, so they decided that the older brother celebrate the Duan Festival at his home and the younger brother celebrate the Mao Festival at his home. Since then Shui people have spent the festival with members of the same clan. ~

Before the Duan Festival, every family sweeps their yard and tidies up their house. The day before their feast day, villagers beat drums and gongs to say goodbye to the old year and meet the New Year. They butcher chickens and ducks and eat newly harvested rice. They also stew soup with fresh fish and prepare a delicious soup to entertain relatives and friends. At New Year's Eve (the night of Dog) and the first morning of the New Year (the Pig day) villagers offer sacrifices to ancestors. They avoid eating meat except fish, and there is no meat except fish in the offerings. The main dish in the offerings is fish stuffed with chives, because, Shui legends, that the ancestors used to drive out all kinds of diseases with a medicine made of nine kinds of vegetables, fish and shrimp. To make the fish: put chives and condiment like chili, onion, ginger and garlic into the fish’s stomach and boil or steam the fish in clear water after it is tied up. ~

During the Duan Festival, young men and women gather around the "Duan slope" to play instruments, sing and dance. And all kinds of entertaining activities are held there, such as horse races, bullfight, theatrical performances, films, and feasts with relatives and friends. Sometimes over ten thousand people—including Miaos, Dongs, Bouyeis, Zhuangs, Yaos and Han—show up and take part in the festival. ~

Shui Wedding Ceremonies and Marriage Customs

According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “By the twentieth century, certainly, the Shui followed the Han marriage pattern, but in more traditional times marriages involved courtship and free choice. Elopements still occurred after Sinicization, as did delayed-transfer marriages, in which the bride did not join her husband's family until she bore her first child. Unlike the Chinese, the Shui allowed divorce and widow remarriage. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

The process of getting married has four stages; inquiring, offering, engagement, and getting married, with a matchmaker carrying out the inquiring and offering. Before marriage, young men and women have traditionally made friends, fallen in love and taken sex partners through a courting process that involved antiphonal singing (alternate singing by two choirs or singers) at festivals and markets. If a couple decided to get married, things became more serious and formal, with set rules that needed to scrupulously followed and the involvement of parents. When a couple decides to get married they first have ask someone to tell the heads of their families. If the head of the man’s family agrees, the man's side asks a matchmaker to send presents to the woman's side and chooses a lucky day to settle the terms of the betrothal. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China ~]

On the wedding day, the groom's family sends some unmarried men to escort the bride to their house. The bride walks all the way to her husband's home under an umbrella and returns to her parent's home on the same day or the day after. The men that escort the bride carry pigs to the woman's home to "have formal wine". A feast is prepared and toasting songs are sung. After the hostess sings a song, the guests drink a toast and express their gratitude to the host by getting drunk and having a good time. Family members of both sides generally don't join in the rite of meeting and sending bride as is the case with many ethnic groups. In some places, the bride is carried by her brother to her husband's home. The richly-dressed bride usually holds a red umbrella which has been torn tear intentionally and walks ahead with best men, and bridesmaids and people carrying her dowry following her closely. The bride usually leave her parents' home at noon, arrived at her husband's home at six or seven in the evening. She can't enter the house until a set lucky tim comes. Relatives of the bridegroom leave the house before the bride reaches, and can't enter until the bride enters the house. ~

The bride traditionally did not live with her husband until six months after marriage but that custom is generally a thing of the past. On her wedding night, the bride sleeps with her bridesmaids and she goes back to live in her parents' home the next day. Later the bridegroom goes to meet the bride and they begin life of man and wife. Some brides stay at their parents' home for one or two months when they go back for first time after wedding, which is called "staying home" or "not settling down in the husband's home".

Sui Wedding

Thunder and change of weather are taboo when the bride is on her way to the wedding, so the wedding are usually held in autumn. If a bride's party encounters another bride on the way to the groom’s family they must detour to another path. Divorced women cannot return to their mother's village for a month after the divorce and a widow cannot go back to the ex-husband's home if she remarries According to the Chinese government: “Such feudal ways as parental arrangement of children's marriages and extortion of big payments by parents of brides from the grooms' families have ceased to exist following the establishment of the People's Republic in 1949. [Source: China.org]

Shui Customs and Life

The Shui generally live in villages in well-constructed two-story wooden houses with railings and the top floor for humans and the bottom floor for animals. They practice wet land rice farming and eat fish as their primary source of protein. Often times brides don’t move in with their husbands until after the first child is born. Before Communism they used to hold elaborate funerals with animal sacrifices, dancing and singing.

Shui people have a clan based hierarchy. A village elder of some seniority has traditionally presided over domestic disputes and family issues. Whenever one family holds a wedding or funeral ceremony, support is provided by other members of the clan. The clan often possesses its own cemetery, scared forest, grass, water source, fish pond and river. Men mainly plough and harrow the fields, feed the cows, horses, transport the farmyard manure, and harvest grain; women are in charge taking car of the house and children, planting rice seedlings, and taking care of the fields and vegetable gardens. The Shui pay attention to family image. Families with the same surname live together as a clan, whose members obey the clan rules. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

Shui elders usually call the younger people "Xiaomei", or little beauty, no matter their gender. When you communicate with them, you cannot use "mud brain" which has an insulting meaning like "idiot". When you are invited to a person's home you cannot cross your legs. Women and children in the family cannot eat until the guests and male residents finish eating.

A Shui house is either a one-storied or a two-storied building. The traditional house is a "pile dwelling" structure made from fir and pine wood and covered by fir bark or tiles. Dwellers of two-storied houses usually live upstairs and reserve the ground floor for livestock, dogs and chickens. The number of the rooms is one, three, five, or seven; it's considered taboo to have even numbers. The Shui diet is dominated by of rice and fish, supplemented with corn, barley, wheat and sweet potatoes. A kind of liquor made of rice goes to entertain guests or is offered to dead ancestors at sacrificial ceremonies. [Source: China.org]

Shui Village in Sandu Shui Autonomous County in Guizhou

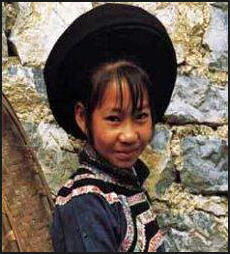

Shui Clothes

The Shuis have traditionally dressed in black and blue. Shui men's clothes look more or less the same as those of the Han Chinese living around them. In the past they wore long gowns and black turbans, and women wear collarless blue blouses, black trousers and aprons, all of which were embroidered. At festival occasions, females put on skirts and a variety of silver earrings, necklaces and bracelets. They usually wear their hair in buns and wear short pants under their skirts. Girls wear elaborate silver necklaces during festivals.. [Source: China.org]

Some Shui women still wear traditional clothes and adornments unique to the Shui. "Suijia cloth"(or Jiuqian black cloth) woven by Shui women has delicate and well-distributed yarns and is dyed black, blue and green. The Shui custom of printing and dying with soya-bean milk is said to have a history of more than 700 years, and articles printed and dyed in this way continue to be deeply loved by the Sui. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China]

Clothes of the Shui women are mostly sewed with Suijia cloth, and consist mainly of a mid-length gown with wide front and no collar or a long gown. Long gowns cover knees and usually have no embroidered lace. Garments worn to festivals and weddings are totally different than common everyday wear. Shoulders, cuffs of sleeves and knees of trousers are decorated with embroidered flowery strips. Colorful designs are featured on scarves. Silver headdresses, silver neckbands, silver bracelets, silver breast plates, and silver earrings are worn at festive occasions with embroidered shoes. String embroidery is a developed, artistic craft. The "string" is actually a piece of "T"-shaped "curtain" with embroidery on both ends of the upper edge of two girdles. Big enough to wrap children, it is sewed with white horse tail tied with white silk threads. Other colors of silk threads are added into it, too. Different designs are embroidered separately and the string is made by piecing together the embroidered designs on cloth. The string is beautiful and useful, and is the best present sent by mother to her daughter when she gets married. ~

Unmarried Shui women like to make informal dress-long gowns with light blue, green or gray cloth and wear them with an upper garment mostly made of silk and satins. The body and the sleeves are tight, accentuating the women's graceful figure. Unmarried women also wear an embroidered long gown, with a black or white long scarf. Married women wear a gown with strips of blue embroidered cloth on the cuffs, around the shoulders and around the bottom of trousers legs. Their long hair is combed and coiled at the top of the head and fixed with a comb inserted from the right side of the coil. Some women wear white girdle or wrap head their with a square scarf with colorful checks. ~

Shui Culture

The Shuis boast a colorful tradition of oral literature and art. Their literature includes poetry, legends, fairy tales and fables. Among the various forms, poetry, which consists of long narrative poems and extemporaneous ballads, are generally considered the most prominent. Stories and fables in prose style praise the diligence, bravery, wisdom and love of the Shui ethnic group and satirize the stupidity of feudal rulers. With rich content and vivid plots Shui tales are usually highly romantic. [Source: China.org|]

Shui songs, which are usually sung without the accompaniment of musical instruments, fall into two categories: "grand songs" are sung while they work, whereas the "wine songs" are meant for wedding feasts or funerals. "Lusheng Dance" and "Copper Drum Dance" are the most popular dances enjoyed by all on festive occasions. Traditional musical instruments include gongs, drums, lusheng, huqin and suona horns. The Shui people make beautiful handicrafts — embroideries, batiks, paper cuts and woodcarvings. |

Shui Rice Producing Customs

The economy of Suis has traditionally revolved are typical rice farming on hillside fields. As early as 150 years ago, 80 percent of the cultivated areas in settlements of the Suis were used to grow rice. The Shui peasants have some special and unique agricultural customs. Whenever possible Shui farmers prefer to use manure instead of chemical fertilizer and they have a special way of preparing it called “stepping on manure with cattle to collect manure.” The Shui raise farm cattle in folds. When cattle rest, they put green grass left over by cattle in the fold, put some soil to pad the fold at the right moment, and let the cattle mix the dung, grass and soil together to make compost. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China ~]

The Shui use a raking tools is to smash the mud lumps in field and make the soil level, which allows the rice grow in loose soil and get water evenly. Many farmers do this. What is special about the Shui is that they use a "boat rake" and "wooden rake" to rake fields. A "boat rake" is a wooden boat-shaped rake about one meter long. The bottom of the "boat" is flat with wooden or bamboo teeth installed below. If it is pulled by people, soil or stones are put in the "boat"; if it is pulled by cattle, a person stands on it to control it. A stone rake is a rectangle stone with holes drilled in it for tying a rope to draw. Rough lines are carved at the bottom of the stone. The main function of the stone rake is not raking but to make the field flat. To irrigate their fields the Shui build small reservoirs in valleys above rice fields or build river dams to save water. Ditches are dug to channel water to the fields. Old water-promoting devises such as tube wheels and turning wheel (dragon bone wheel), are used in places where fields are higher than water. ~

"Huolutou" means "the leader of farming" in a local Han dialect. Important farm work in Shui villages, such as ploughing fields, raising rice seedlings, transplanting rice seedlings and harvesting have traditionally been done only after the "Huolutou" gave the order to do them. When farming season comes, the "Huolutou" chooses a lucky day and holds simple rites. He symbolically ploughs a line of field, transplants several rice seedlings, or cuts some bundles of rice, signaling others can begin to do the same work in their contracted fields. This kind of custom has at least two meanings: one is the importance of agricultural production; the other is that the "Huolutou" is skilled at growing crops.

There is a clear division of agricultural labor according to gender in Shui areas. The tradition is that "women don't plough and men don't transplant rice seedlings", and anyone who violates the rule would suffer a sharp rebuke. In the past, women in families that lacked men disguised themselves as men and ploughed their fields at night. Men do work like ploughing fields and reinforce ridges because great physical strength is needed to struggle with these chores in the mud and water, and the work is regarded as too difficult for women. This doesn't mean that women’s work is not hard. Transplanting rice seedlings, cutting rice stalks, and carrying rice can be especially hard on the back and requires a lot of bending over. The Shui like to say that such labors make it seem like the waist is "going to break". ~

Image Sources:

Text Sources: 1) “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China”, edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company; 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China *\; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2022