TAJIKS IN CHINA

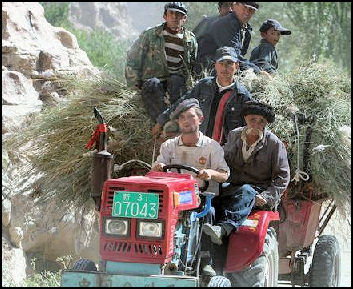

Tajiks on a tractor

Tajiks are a Persian-speaking Muslim group that lives in Western China around the snowcapped Pamirs, a mountain range shared with Tajikistan and Afghanistan. Related to ethnic groups in Afghanistan and Iran, the Tajiks are perhaps the most non-Chinese-looking people in China. They have copper-colored skin, round eyes and Caucasian features and some have blue eyes, freckles and red hair. Some believe they are descendants of subjects of Alexander the Great. Tajik in an Indo-European language closely related to Persian. This is maybe the only Indo-European language at least sort of indigenous to China. The Chinese refer to the Pamirs as the "roof of the world" and many of the people that live here have little contact with the outside world. When a National Geographic photographer told a small a boy he lived in Paris, the boy asked him how many sheep he owned.

The Tajik live mainly in the Tajik autonomous county — Taxkorgan (Tashkurgan) Tajik Autonomous County in Xinjiang — in the southwestern part of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. This is near the borders of Tajikistan, Pakistan and Afghanistan. A small number of them are scattered in Shache, Zepu, Yecheng, Pishan and other border regions in the western part of the Tarim Basin. Millions of Tajiks live in Afghanistan, Taijikistan and elsewhere in the former Soviet Union. The Tajiks in Taxkorgan live alongside Uygurs, Kirgizs, Xibes and Hans.[Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences]

Tajiks are regarded by Chinese as firm, persistent, bold and unconstrained. In their legends, the hawk is the symbol of hero. The favorite instrument of Tajik herdsmen is a short flute called a "nayi" that is made of hawk's wing bones. In some of the dances the Tajik imitate the graceful movements of flying male hawks. Before the founding of the People’s Republic of China, Tajik ethnic people mainly engaged in animal husbandry, supplements by agriculture, living a half-nomadic, half settled life. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, agriculture and animal husbandry developed quickly, and industry was developed from scratch. \=/

Tajik are the 38th largest ethnic group and the 37th largest minority out of 55 in China. They numbered 51,069 and made up less than 0.01 percent of the total population of China in 2010 according to the 2010 Chinese census. Tajik population in China in the past: 41,056 in 2000 according to the 2000 Chinese census; 33,538 in 1990 according to the 1990 Chinese census. A total of 14,462 were counted in 1953; 16,236 were counted in 1964; and 27,430 were, in 1982. Around 6 million Tajiks live in Tajikistan. They make up 80 percent of the population there. Many also live in Afghanistan. Chinese Tajiks belong to the Sarikol and Wakhi clans.[Sources: People’s Republic of China censuses, Wikipedia]

See Separate Articles Uyghurs and Xinjiang factsanddetails.com and Small Minorities in Xinjiang and Western China factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Xinjiang Wikipedia Article Wikipedia Xinjiang Photos Synaptic Synaptic ; Maps of Xinjiang: chinamaps.org; Wikipedia List of Ethnic Minorities in China Wikipedia ; People’s Daily (government source) peopledaily.com.cn ; Muslims in China Islam in China islaminchina.wordpress.com ; Islam Awareness islamawareness.net ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:“A History of the Tajiks: Iranians of the East” by Richard Foltz Amazon.com; “Familiar Strangers: A History of Muslims in Northwest China”by Jonathan N. Lipman Amazon.com; “Securing China's Northwest Frontier” by David Tobin” Amazon.com; Muslims: “Islam in China” by James Frankel Amazon.com; “China and Islam: The Prophet, the Party, and Law (Cambridge Studies in Law and Society) by Matthew S. Erie Amazon.com ; “Ethnic Identity in China: The Making of a Muslim Minority Nationality” by Dru C. Gladney Amazon.com; “Ethnographies of Islam in China” by Rachel Harris, Guangtian Ha, et al. Amazon.com; “Muslim Chinese: Ethnic Nationalism in the People’s Republic (Harvard East Asian Monographs) by Dru C. Gladney Amazon.com; Xinjiang: “Xinjiang: China's Central Asia” by Jeremy Tredinnick Amazon.com; “Xinjiang and the Modern Chinese State” by Justin M. Jacobs Amazon.com “Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland” by S. Frederick Starr Amazon.com; Herders: “China's Last Nomads: History and Culture of China's Kazaks” by Linda Benson and Ingvar Svanberg Amazon.com; “Winter Pasture: One Woman's Journey with China's Kazakh Herders” by Li Juan, Nancy Wu, et al. Amazon.com

Tajik History

Taxkorgan (in pink) in light grey Xinjiang, where most Tajiks live

The origin of the Tajik ethnic group can be traced to tribes speaking eastern Iranian who had settled in the eastern part of the Pamirs more than twenty centuries ago. In the 11th century, the nomadic Turkic tribes called people "Tajiks" who lived in Central Asia, spoke Iranian and believed in Islam. Tajik people who had lived in various areas of Xinjiang and those who had moved from the western Pamirs to settle in Taxkorgan at different times are ancestors of the present-day Tajik ethnic group in China. The ancient tomb of Xiang Bao Bao, found through archaeological excavation in recent years in Taxkorgan, is the oldest cultural relic ever discovered in the westernmost part of China. Many burial objects were found in this 3,000-year-old tomb. [Source: China.org |]

In the 2nd century before Christ, Zhang Qian, an imperial envoy, explored to the Western Regions (including what is now Xinjiang and parts of Central Asia). The government of the Western Han Dynasty established an administration in the Western Regions. The Taxkorgan Region was the main transportation artery and strategic passage of the Silk Road. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

In the late 18th century, Tsarist Russia took advantage of the turmoil in southern Xinjiang to occupy Ili and intensified its scheme to take control the Pamirs of China by repeatedly sending in "expeditions" to pave the way for armed expansion there. In 1895, Britain and Russia made a private deal to dismember the Pamirs and attempted to capture Puli. Together with the garrison troops, the Tajik people defended the border and fought for the territorial integrity of the country. At the same time, Tajik herdsmen volunteered to move to areas south of Puli, where they settled for land reclamation and animal husbandry while guarding the frontiers. |

See Separate Articles EARLY HISTORY OF TAJIKISTAN factsanddetails.com; HISTORY OF THE TAJIKS factsanddetails.com

Origin of the Tajik

The source and meaning of the Tajik name is still a matter of debate among scholars. According to some "Tajik" is the name of an ancient Arab tribe in the Iraq region. "Tayi" is an ancient term used in many Asian countries to describe Arabs. Around the 10th century, "Tayi" was a name used by Iranians (Persians) to describe Islamic believers. In the 11th century, "Taji" became a word used to categorize nomadic tribes that spoke Turkic language in Central Asia. Later, settled inhabitants of Central Asia who spoke Iranian and believed in Islam were called "Tajik". Afterwards, "Tajik" became the name of the nationality. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China ~]

Tajik Wakhis and Kyrghyz at Dafdar

The Tajik in the Pamirs region of China offer an different explanation. They say that the word "Tajik" originally meant "crown". The Chinese Tajik scholar Xiren Kurban wrote in the book on the Chinese Tajik Nationality that the word "Taji" evolved from the ancient words of "Taji'erda" (person that wears crown) and "Tajiyeke" (sole crown). According to an old folk legend: There was once a hero named Lusitamu who possessed incomparable strength and extraordinary braveness. He defeated all the brutal, dark and mean forces with the spirit of male lion to bring happiness to his people, the ancestors of the Tajik people. ~

Afterwards, the ancient proto-Tajiks were rued by a series of kings: Kaiyihuosilu, Kaiyikubate, Kaiyikawusi, Jiamixide and Nuxiliwang. All of them wore crowns on their heads, and governed a large piece of land from the east to the west. Their subjects manufactured all kinds of bright-colored "Taji" hats that imitated the crowns and wore these on heads to show they were the happy subjects of a just king. Since then, all the kingdoms far and near called them the "Tajikla" (Tajik people). The "tubake" (the Tajik-style man's high hat), known for its exquisite workmanship, and the "kuleta" (the Tajik-style women hat), known for its excellent embroidery, worn by Tajiks today date back to the first Tajik kings and their crowns.

Pamiri Tajiks

Many of the Tajiks in China are Pamiri Tajiks. Around 210,000 people live in the Gorno-Badakhshan region in Tajikistan. About 95 percent of them are Pamiri Tajiks (also known as Pamiris, or Pamirians, or Pamirian Tajiks). There are a few Tajiks, Kyrgyz and Russians. There are also some Pamiri Tajiks in Afghanistan, western China and Pakistan. The Gorno-Badakhshan region embraces most of the Pamirs. It accounts for 45 percent of Tajikistan’s territory but is home to only three percent of its people. The largely Shiite inhabitants of the Pamir mountains speak a number of mutually unintelligible eastern Iranian dialects quite distinct from the Tajik spoken in the rest of the country. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: China, Russia and Eurasia” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company]

Kirill Nourzhanov and Christian Bleuer wrote:“The Pamiris have always differed from other Tajiks in important cultural characteristics, such as language, religion and stronger familial affiliation. Their languages and dialects belong to the Eastern Iranian language group as opposed to the Western Iranian Tajik. The majority of Pamiris adhere to the Ismaili sect of Shiism whilst the bulk of valley and mountain Tajiks are Sunnis. All eight Pamiri sub-ethnic groups retain potent self-consciousness and can identify themselves on at least three levels: by their primary cultural name—for example, rykhen, zgamik, khik and so on—when dealing with one another; by their collective name, pomiri (Pamiri), when interacting with other groups in Tajikistan; and, finally, as Tajiks when outside the republic. In the 1980s, the official line of the Tajik leadership denied the Pamiris their cultural uniqueness: ‘the Pamiris are Tajiks by descent and their languages are nothing more than dialects of Tajik.’ [Source: “Tajikistan: Political and Social History” by Kirill Nourzhanov and Christian Bleuer, Australia National University, 2013]

The Pamiri Tajiks have developed a distinct culture due to their isolation in the mountains. The dialects they speak vary greatly from valley to valley and are often as different from one another as Spanish is from French. Although related to Tajik the Pamari languages often have more in common with ancient Iranian languages like Sogdian, Bactrian and Saka than they do mordern Tajik. Because the languages and dialects are so different from one another and from Tajik, the Dari language of Afghanistan and the Western Iranian Farsi of India often serve as lingua francas. The Pamiris are united most by belief in the Ismaili sect of Islam — a branch of Shiite Islam — and their hospitality.

See Separate Article PAMIRI TAJIKS factsanddetails.com

Caravanserai between_Dafdar and Tashkurgan

Tajik Language and Religion

The Tajik language belongs to eastern Iranian branch of the Iranian group of Indo-European languages. The majority of Tajik people speak Sarikoli dialect while the minority speaks the Wakhi dialect. Both Sarikoli and Wakhi belong to the Pamir language group of the Eastern Iranian language group. Many Tajik people can speak the languages of Uyghurs and Kyrgyz, as members of these groups live near them. Tajiks in China have traditionally used the Uyghur script. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

Tajiks are Muslims. Most belong to the Ismaeli sect of Shiite Islam led by the Aga Khan. They practice ground burial and celebrate Muslim holidays but have no mosques. Instead they have weekly prayer meetings. Animist beliefs remain alive. Many wear amulets — or boxes with Koranic verses written on a piece of paper inside — to ward off evil spirits. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 ]

Tajiks were originally Sunnis. In the beginning of the 18th century, they changed to Nizari Ismaili sect of Shia Islam. Over their long history, Tajik people and their ancestors have embraced many religions, including folk religion, Zoroastrianism and Buddhism. The ancestors of Tajik people worshiped nature and natural phenomenon, especially eagles and hawks, which still have special meaning to Tajiks and are regarded as animal totems worshiped by the ancestors of Tajik people. The Tajiks have been Muslims since the 10th century. The Tajik ethnic minority is the only ethnic group in China who believes in Nizari Ismaili sect of Shia Islam.

See Separate Articles: POPULATION, DEMOGRAPHY AND LANGUAGE IN TAJIKISTAN factsanddetails.com ; RELIGION IN TAJIKISTAN factsanddetails.com ; ISLAM IN TAJIKISTAN factsanddetails.com ; HISTORY OF ISLAM IN TAJIKISTAN factsanddetails.com

Tajik Life in China

The Tajiks have generally been regarded as the poorest ethnic group in western China. Until recently they had virtually no money and bartered their animals and grain for things they need from the outside. Some still live a semi-nomadic life, follow the seasons in their economic activities: raising high land barely, wheat and a few other crops in the spring and early summer and migrating with their animals — sheep, horses, yaks and camels — from their winter homes to summer pastures in the Pamir highlands, where they live in yurts, felt tents or mud huts. They remain there, living in until it is time to return in the fall to harvest their crops. One Tajik man told National Geographic, "People's life is close to the land and the animals. If someday the social system finds a way to give security to the old, then the children will feel free to go." [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Aykarag Village in 2015

Most Tajiks live in small villages in high elevations in thick-walled, flat-roof houses made of wood, sod and stone. The flat roofs are built to collect snow in the winter to insulate the house and reduce fuel needs. In the winter, people stay warm by sitting and sleeping on kangs. Most families have a separate shed for cooking and shelters for animals. |~|

Tajiks tend to live in three-generation households, with the oldest male serving as head of the household. With the exception of a small percentage of marriages to Uyghur and Kyrgyz people, who are culturally similar to the Tajik, Tajiks generally don’t marry non-Tajiks and are very interrelated. Before Communist era, marriages arranged when couples were children, as young as seven, were common. Today there is a payment of bride price, often in gold, silver, animals or clothing. Men often wear fur hats and are known as skilled horsemen. Women wear pillbox-shaped hats hung with veils and jewelry made from silver and coral beads. |~|

The eagle is the symbol of the Tajiks. A popular folk dance represents the flight of an eagle. It is accompanied by music from a hand drum and eagle flute. Tajiks enjoy playing buz kashi, a rough polo-like game played with a sand-filled goat or calf carcass. The game is often played on 10,000-foot-high plateaus in the Pamir mountains.

Tajiks and Their Life in the Pamirs

Tashiku'rgan, the main settlement region of The Tajik, is located in the eastern part of the Pamirs and the northern part of the Karakorums, two of the highest mountain ranges in the world. Not far away is 8,611-meter-high K2 (Qiaogeli Mountain), the second highest mountain in the world. To the north in is "father of iceberg"— 7,456-meter-high Mushitage Mountain. The snow and glaciers are provide water for pastures and farm worked for centuries by the Tajik.

The Tajik have been associated with the Pamirs since the pre-Qin days before the Christian era, In the Silk Road era they controlled important passes in the region. They have engaged in animal husbandry and farming in the area, taking advantage of the ample pasturage and abundant water resources. Every spring, they sow highland barley, pea, wheat and other cold-resistant crops. They drive their herds to highland grazing grounds in early summer, return to harvest the crops in autumn and then spend winter at home, leading a semi-nomadic life. [Source: China.org |]

Over the centuries, the Tajiks have adapted their dressing, eating and living habits to the highland conditions. Most Tajik houses are square and flat-roofed structures of wood and stone with solid and thick walls of rock and sod. Ceilings, with skylights in the center for light and ventilation, are built with twigs on which clay mixed with straw is plastered. Doors, usually at corners, face east. Since the high plateau is often assailed by snowstorms, the rooms are spacious but low. Adobe beds that can be heated are built along the walls and covered with felt. Senior family members, guests and juniors sleep on different sides of the same room. When herdsmen graze their herds in the mountains, they usually live in felt tents or mud huts.

Tajik herdsmen enjoy butter, sour milk, and other dairy products, and regard meat as a delicacy. It is a taboo to eat pork and the flesh of animals which died of natural causes.

Tajik shepherd and his sheep and goats

Marxist View of Tajik Development

According to the Chinese government: “The Tajik people were mainly engaged in animal husbandry and farming, but productivity was very low, unable to provide enough animal by-products in exchange for grain, tea, cloth and other necessities. The economic polarization resulting from heavy feudal oppression was best illustrated by the distribution of the means of production. The majority of the Tajik herdsmen owned very small herds, so that they were unable to maintain even the lowest standard of living, and still others had none at all. A small number of rich herdsmen not only owned numerous yaks, camels, horses and sheep, but held by force vast tracts of pasturage and fertile farmland. [Source: China.org |]

“In the Tajik areas, the chief means of exploitation used by rich herd owners was hiring laborers, who received only one sheep and one lamb as pay for tending 100 sheep over a period of six months. The pay for tending 200 sheep for the herd owner for one year was just the wool and milk from 20 ewes. Herd owners also extorted free service from poor herdsmen through the tradition of "mutual assistance within the clan." |

“Tajik peasants in Shache, Zepu, Yecheng and other farming areas were cruelly exploited by the landlords. In those areas, "gang farming" was a major way of exploitation. Besides paying rent in kind that took up two-thirds of their total output, tenants had to work without pay on plots managed by the landlords themselves every year, and even the peasants' wives and daughters had to work for the landlords. There was practically no difference between tenants and serfs except that the former had a bit of personal freedom. |

“There were all kinds of taxes and levies in both pastoral and rural areas. Especially during the 1947-1949 period, the Tajik herdsmen in Taxkorgan were forced to hand in more than 3,000 sheep and 500 tons of forage and firewood a year to the reactionary government. Poverty-stricken under heavy exploitation, the Tajik people were unable to make a decent living, and widespread diseases reduced their population to just about 7,000 when Xinjiang was liberated in December 1949. |

“In 1954, the Taxkorgan Tajik Autonomous County was founded on the basis of the former Puli County where the Tajik ethnic group lived in compact communities. At the time of China’s national liberation in 1949, Taxkorgan had only 27,000 animals, two per capita of the total population in the county; total grain output was 850 tons, 55 kg per capita. Since 1959, the county has been self-sufficient in grain and fodder and able to deliver a large number of animals and quantities of furs and wool to the state each year. Several hundred hectares of new pasture and grassland have been added in recent years. There was no factory or workshop in Taxkorgan before 1949, and even horseshoes had to come from other places. Now more than 10 small factories and handicraft workshops have been built, such as farm and animal husbandry machine factories, hydroelectric power stations and fur processing mills. Mechanization of farming and animal husbandry has expanded. Veterinary stations have been built in most communities. Tajiks have been trained as veterinarians and agro-technicians. Tractors are being used in more than half of the land in the county. One breed of sheep developed by the Tajik herdsmen is among the best in Xinjiang. |

Taxkorgan was a backward, out-of-the-way area before 1949, when it would take a fortnight by riding a camel or a week on horseback to reach Kashi, the biggest city in southern Xinjiang. In 1958, the Kashi-Taxkorgan Highway was completed, shortening the trip between the two places to one day. In the town of Taxkorgan, the county seat, which is perched right on top of the Pamirs, wide streets link shops, the hospital, schools, the post office, bank, bookstore, meteorological station and other new buildings in traditional architectural style and factories under construction. Great changes have also taken place in many mountain hamlets, where shops and clinics have been built. The herdsmen and peasants are enjoying good health with the improvement of living conditions and medical care. Since 1959, schools have been set up in all villages, and roaming tent schools have been run for herdsmen's children. Many young Tajiks have been trained as workers, technicians, doctors and teachers. The Tajik people's living standards have improved considerably with the steady growth of the local economy. A growing number of herdsman households have bought radios and TV sets. |

Tajik Festivals

Some Tajik festivals are in line with Muslim celebrations; others go bacl further to their Persian, Zoroastrian roots. The beginning of the Fasting Month marks the end of a year. On this day, every family will make torches coated with butter. At dusk, the family members get together, have a roll call and each will light a torch. The whole family will sit around the torches and enjoy their festive dinner after saying their prayers. At night, every household will light a big torch tied to a long pole and planted on the roof. Men and women, young and old, will dance and sing through the night under the bright light of the torches. The Islamic Corban festival is another important occasion for the Tajik people. [Source: China.org|]

The Tajik spring festival, which falls in March, marks the beginning of a new year, which is the most important occasion for the Tajik people. Every family will clean up their home and paint beautiful patterns on the walls as a symbol of good luck for both people and heads. Early on the morning of the festival, members of the family will lead a yak into the main room of the house, make it walk in a circle, spray some flour on it, give it some pancake and then lead it out. After that, the head of the village will go around to bring greetings to each household and wish them a bumper harvest. Then families will exchange visits and festival greetings. Women in their holiday best, standing at the door, will spray flour on the left shoulder of guests to wish them happiness. |

"Pilik" is a Tajik summer festival. "Pilik" means "lamp" or "wick", and thus the event is called the "lamp festival". Pilak lasts for two days and is usually held in mid August or the middle of the eight month of the Muslim lunar calendar. The form and contents of the Pilik Festival are actually closely related with fire. Many believe the festival dates back to pre-Islamic times when Tajiks practiced Mazdaism (Zoroastrianism), which has special rituals involving sacred fire. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences ~]

On the eve the Pilik festival, each family makes many small lamps and candles and a very big light by themselves. They make homemade “candles by wrapping cotton around a wick made from special "kawuri" grass, binding the whole thing together with butter or sheep's oil. On The first evening of the festival is "home Pilik". After it becomes dark, family members sit on the kang in a circle, insert their lamps and candles into a sand table placed in the middle of the kang. The head of the family chairs a ceremony which begins with everyone praying. The family head then calls every family member's name according to the order of their ages and seniority in the family. When family member’s name is called, he or she answers and places a lighted candle before himself or herself to pray for luck. After the lamps and candles of all the family members are lit, all of them extend out both hands to warm them for while over their own lamps. They then read and recite some Muslim scripture and pray to the Allah to bring happiness and make sure everyone is safe. When the ceremony ends, all the family members feast on sumptuous delicacies under the glimmering candlelight. ~

On the second day of Pilak, people visit relatives and friends and congratulate each other. In the evening, the "grave Pilik" ceremony is held. All families will bring rich foods to the graveyard of their clan, and pray for the souls of their ancestors before lit lamps and candles placed in the graveyard. All family members sit down in a circle a share food together. After the grave Pilik ceremony ends, all the families prepare their biggest lamp, hang it on the roof of house and lit it. This is called the "heaven lamp". All family members solemnly stand before the house, and look up at the "heaven lamp" and pray for happiness again. Then, the children light bonfires outside the house one after another, and surround them, happily singing, dancing and playing games.

See Separate Article HOLIDAYS AND FESTIVALS IN TAJIKISTAN factsanddetails.com

Tajik Marriage and Family

Tajik have traditionally lived with their extended family. When the father is still alive, the sons rarely leave the house to live on their own; otherwise they will be blamed by others. There are three generations or even four generations living together under the same roof in many families. In most cases, three generations of a Tajik family live under the same roof. The male parent is the master of the family. Women have no right to inherit property and are under the strict control of their father-in-law and husband. [Source: China.org |; Chinatravel.com \=/]

In the past, the Tajiks seldom had intermarriages with other ethnic groups. Such marriages, if any, were confined to those with Uygurs and Kirgizs. Marriages were completely decided by the parents. Except for siblings, people could marry anyone regardless of seniority and kinship. Therefore marriages between cousins were very common. Usually the husband should be older than his wife. Among Tajik people, witnessing the whole course of their children’s marriage is a sacred duty for parents. Getting divorce, leaving the wife or the husband is shameful. Therefore, most of the Tajik couples are single-minded each other and remain a devoted couple to the end of their lives. | \=/

The wedding ceremony is complicated, with processes of choosing the spouse, courtship, proposal, engagement and many other processes. The whole wedding ceremony is filled with singing and dancing. After the young couple was engaged, the boy's family had to present betrothal gifts such as gold, silver, animals and clothes to the girl's family. All relatives and friends were invited to the wedding ceremony. Accompanied by his friends, the groom went to the bride's home, where a religious priest presided over the nuptial ceremony. He first sprayed some flour on the groom and bride, and then asked them to exchange rings tied with strips of red and white cloth, eat some meat and pancake from the same bowl and drink water from the same cup, an indication that they would from that time on live together all their lives. The following day, escorted by a band, the newlyweds rode on horseback to the groom's home, where further celebrations were held. The festivities would last three days until the bride removed her veil. |

Childbirth is a major event for the Tajiks. When a boy is born, three shots will be fired or three loud cheers shouted to wish him good health and a promising future; a broom will be placed under the pillow of a newborn girl in the hope that she will become a good housewife. Relatives and friends will come to offer congratulations and spray flour on the baby to express their auspicious wishes. |

See Separate Articles: MARRIAGE AND WEDDINGS IN TAJIKISTAN factsanddetails.com ; FAMILIES, MEN, WOMEN AND CHILDREN IN TAJIKISTAN factsanddetails.com ; TAJIK SOCIETY factsanddetails.com ; TAJIK HOMES, VILLAGES AND URBAN LIFE factsanddetails.com

Tajik Food and Customs

The best food is finger meat (meat eaten directly using the hands, rice boiled with milk, and pancakes boiled with milk. The diet and preparation methods of their diet fully reflect the economic conditions, everyday needs and ethnic features. In grazing areas, their foods are mainly dairy, pastry and meat. While in farming areas, their foods are mainly pastry, accompanied by dairy and meat. Pastry is mainly Rang (a kind of crusty pancake) made from flours of wheat, barley, corn and beans. Their foods feature milk porridge, milk noodle flakes, milk paste, butter tea wheat paste, butter tea milk paste, butter tea highland barley rang (crusted pancake), butter tea sprinkled on rang, finger meat, finger rice, cheese, dried milk and milk tea. There are some taboos in their diet. It is forbidden to eat animals that are not slaughtered, or animal’s blood, the meat of pig, horse, donkey, bear, wolf, fox, dog, cat, rabbit and marmot. People should pray before they slaughter the animals.

The Tajik people pay great attention to etiquette. Juniors must greet seniors and, when relatives and friends meet, they will shake hands and the men will pat each other's beard. Even when strangers meet on the road, they will greet each by putting the thumbs together and saying "May I help you?" For saluting, men will bow with the right hand on the chest and women will bow with both hands on the bosom. Guests visiting a Tajik family must not stamp on salt or food, nor drive through the host's flocks on horseback, or get near to his sheep pens, or kick his sheep, all of which are considered to be very impolite. When dining at the host's, the guests must not drop left-overs on the ground and must remain in their seats until the table is cleaned. It would be a breach of etiquette to take off the hat while talking to others, unless an extremely grave problem is being discussed. [Source: China.org]

See Separate Article FOOD AND DRINKS IN TAJIKISTAN factsanddetails.com

Tajik Clothes

Tajik are mainly dress in cotton-padded clothes and vests, with a little difference for the four seasons, because of the very cold and highland climate conditions of the Pamirs. The clothing and decorations of the Tajik herdsmen, who live in the Pamirs, has been described as "the colored clouds on the roof of the world". Both men and women wear felt stockings, long soft sheepskin boots with yak skin soles, which, light and durable, are suitable for walking mountain paths. Women are deeply fond of dressing themselves up, and their accessories and styles vary according to ages and marital status. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, ~; China.org |]

Tajik veil from 1779

Traditionally-dressed Tajik men wear a black or blue long coat with no collar and with buttons down the front outside a white shirt. They wear a belt around the waist, with a knife hanging on the right side along with long-leg boots made of male goatskin. Men sometimes add sheepskin overcoats over their coats in cold weather. For headgear they wear a round rolling-hem high hat with black lamb's skin as lining and black velveteen decorated with lines of embroidery on the outside. The flaps can be turned down to protect ears and cheeks from wind and snow. They have traditionally worn these clothes when they rode their fine horses between the pastures and snowy mountains under blue sky and white clouds of the Pamir region.~ |

National Palace Museum, Taipei has a Tajik Lace veil with tassels presented from Yengisar in 1779, According to the museum: This lace veil is an item used in Tajik women's wedding. The lace veil, weaved in a rather unique way, features a hollow square added with silk threads to produce geometric patterns. The lace veil is one of the few surviving works of such designs from the eighteenth century. The upper edge of the veil was embroidered with guipure embroidery, one side of which comprises grass-patterned red velvet strips in gold silk threads, and the other side of which contains flower-patterned blue fabric strips in silk threads. The aforementioned embroidery techniques and designs are common in Central Asia. The lace veil is attached with two sets of bands, one set of which consists of a red cotton thread decorated with a silver silk thread knot, and the other is made up of a gold silk thread decorated with a pearl knot and a gemstone pendant with gold inlay. For the latter, gold pearl-based geometric patterns were employed to form its golden accessories, which were embedded with red and green gemstones, exemplifying a typical Islamic style. This veil was made in Yengisar, a city under the administration of Kashgar, which was a gathering place west of China linked with the northern, central, and southern routes of the Silk Road in ancient times. Trading between countries in Central Asia bloomed during the time of the Silk Road, and the lace exhibited here truthfully exemplifies the multicultural elements observed along the Silk Road. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei]

See Separate Article ART, CLOTHES AND GOLD TEETH IN TAJIKISTAN factsanddetails.com

Hawks and Tajik Culture

The Tajiks have rich and colorful culture. In the past, there were no scripts, and all the arts were passed on orally. Tajik drama comes in two kinds: song and dance drama and stage plays. The dialog is often humorous and the movements are amusing, with symbolic meanings. The main Tajik handicrafts are embroidery, weaving and applique. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

The Tajik have always had names that associated them with hawks (or eagles) such as the "hawk nationality", "people of hawk" and "Pamirs hawk". The hawk is a symbol of the Tajik people and various dances, legends and music linked to the birds are distinguishing characteristics of Tajjik culture. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China ~]

Legends with hawk as the source of Tajik creation account for a considerable proportion of Tajik folk legends. There are at least 10 such stories. A popular one goes: Once there was a pair of male and female youth servants who loved each very much but suffered in the home of an evil bayi (landlord). The jealous bayi murdered the girl servant who became a hawk and gets her revenge against the bayi. In the folk songs of The Tajik, hawks are depicted as the head of all birds, and are deeply praised by people. Some songs highly praise heros, patriots and fearless warriors by equating them with hawks. Other songs praise the pure love, justice and virtuous behavior and lash out against cruelty, oppression, greed and envy using hawk imagery. Famous Tajik long poems—The Male Hawk, The White Hawk and Taihong—all belong to this type. Many Tajik folk proverbs feature a hawk. For example, "Though the peacock is the most beautiful, it cannot fly as the hawk"; "The clever hawk does not deal with foxes"; "The crow who disguises itself as hawk fears the hawk most". ~

The Tajiks have a gift for music, singing and dancing. They have singing songs, dancing songs, lamb tussling songs, love songs, religious songs and other forms of songs. Their unique musical instruments are the, Balangzikuomu (a seven-stringed plucked musical instrument) and Repupu (a six-stringed plucked musical instrument). Among the instruments that accompany their dances and songs is the "nayi", a kind of flute made from wing bones of wild hawk. Its sound has been described as “sonorous, loud and clear, sweet and agreeable. On the birth of this hawk flute, there are many Tajik legends. One goes: long ago, foreign invaders invaded Tajik villages and Tajik herdsmen became isolated. At that time, the Tajik villagers killed a hawk very reluctantly according to its request, and used its wing bones to make a flute. The sound of flute was solemn, stirring and intense, able to split stones and penetrate clouds. Tajiks from afar rushed to help and save their besieged brothers one after another from all directions. Innumerable male hawks joined the fighting teams, and the invaders were driven away. ~

Tajik dances are usually performed by two people, featuring with the imitation of hawks or eagles. The Tajik hawk dance—regarded as the most important Tajik folk dance—expresses the Tajik’s love and yearning for good life by imitating the movements of a male hawks freely flying in the blue sky between the white clouds. When the men dance, one arm is at the front, and the other is at the back, the front arm is held up highly, and the back arm is lower, and the steps are quick. At the time of slow dancing, the two shoulders slightly shiver from up to down; at the time of rapid dancing, they rotate at a violent speed, just like a rising and falling hawk. When the women dance, they hold up the hands highly and sway unceasingly with the rhythms of music, rotating continuously, the whole set of movements are tender and steady and give people a sense of beauty. ~

Tajik Legend of the "Princess Castle"

Sights in Tashikurgan—the Tajik-Pamirs region of far western China include the Stone Town, Princess Castle, Alaimuger Castle, Xiangbaobao Ancient Graves, Gaizi River Ancient Courier Station and Bamafeili wailimazha. Chief among them is the Princess Castle, which is located on a mountain about 10 kilometers to the south of Dabuda. Tajik people take great pride in this ancient relic. According to legend, in the ancient times, Tashikurgan was a vast deserted plain on the Congling (the present Pamirs). When Silk Road traders began passing through the region it became a busy trading hub and a place full of vigor. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China ~]

Afterwards, a Han Chinese princess from the Central Plains of China accepted the marriage request of a Persian king, and embarked on a journey to Persia. She arrived in Congling at the time a war happened and the road was blocked and and she was forced to seek shelter on deserted high plateau. A Persian ambassador was sent to take care of her. He ordered his guards to closely guard her and protect her. While the princess was on the plateau she was united in wedlock with the solar god a of mountain in the area and became pregnant. The ambassador did not dare report this news back to the Persian king. Instead he ordered his soldiers and guards to construct a palace and town on the mountain for the princess to settle in. ~

The princess gave birth to a clever and handsome boy. When he grew up, he became the king of his Pamir homeland and established the Jiepantuo Kingdom, which means "mountain road". People called the capital "Kezikurgan", which means the "princess castle". There is a strong current of Chinese propaganda to this legend. According to Chinese government sources: “Since then, the royal family of the Jiepantuo Kingdom called themselves "the natural race of the Han nationality and the sun", and called their first ancestor mother as the "person of Han nationality". ~ According to historical documents, Jiepantuo Kingdom was another name for the Fang Kingdom, established by the ancestors of the Tajik in what is now far-west Xinjiang in the A.D. 2nd century and disappeared in the 8th century. However, the ruins of what is described as the princess castle is still present. ~

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, China Daily, Chinese government

Text Sources: 1) "Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China", edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K.Hall & Company, 1994); 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China < *\; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2022