NORTHWEST CHINA AND ITS PEOPLE

Geographically and culturally part of Central Asia, Northwest China region includes western Gansu, Xinjiang, Ningxia, and part of Inner Mongolia. According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “The topography is highly varied and includes large stretches of arid desert and wasteland, fertile oases, grassy plateaus, and high mountain ranges. The Altai range rises to more than 4,000 meters above sea level and the Tianshan to 7,435. The climate is generally dry, averaging only 10 centimeters of rain yearly in some areas. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Geographically and culturally part of Central Asia, Northwest China region includes western Gansu, Xinjiang, Ningxia, and part of Inner Mongolia. According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “The topography is highly varied and includes large stretches of arid desert and wasteland, fertile oases, grassy plateaus, and high mountain ranges. The Altai range rises to more than 4,000 meters above sea level and the Tianshan to 7,435. The climate is generally dry, averaging only 10 centimeters of rain yearly in some areas. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Population is sparse in the grassland and in mountain pastureland; in many places it is less than one person per square kilometer. The region is China's main source ofsheep, cattle, horses, and camels. Some areas are suited to grain and cotton production. There are relatively few cities: the largest are Urumqi, and Kashgar, which were stages on the old Silk Road. A large percentage of the population belong to minority nationalities: Uyghurs, Hui, Kazak, Kyrgyz, Mongols, Tajiks, and others. , and almost one-third of Ningxia's population are Hui. Because of heavy Han immigration, Mongols are now no more than 15 percent of the population of the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region.

A large portion of Northwest China is taken up by Xinjiang, China's westernmost region and largest political entity. Larger than Alaska and occupying roughly one sixth of China's total area, it is covered mostly by vast, inhospitable desert punctuated here and there by bazaar towns, ancient ruins, oil camps, and Chinese cities with discos and shopping malls, with massive snow-capped mountains in the west and south.

The majority of the speakers of Turkic languages, the Western Branch of Altaic, are located in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region and in the western republics of the former Soviet Union. According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “They include Kazaks, Uyghurs, Kyrgyz, Uzbeks, and Tatars. During the Republican period (1911-1949) all Turkic speakers within China were referred to as “Tatars," but in actuality there are less than 5,000 Chinese Tatars; they live in Xinjiang, near the Soviet border. There are well over a million Kazak speakers within China, along the Mongolian and former Soviet borders, speaking a language closely related to Tatar. Kyrgyz, found in western Xinjiang, has 142,000 speakers and is closely related to Tatar and Kazak. China also holds a small population of 14,000 Uzbek speakers, but the vast majority of speakers of this Turkic language live in Uzbekistan. The Uyghur, who number over 7 million, are the predominant group of Turkic speakers within China. Their language is relatively unified because of complex commercial relations throughout the region and a long history of alphabetic writing systems. A rich literature of poetry and writings on Buddhist and Nestorian teachings exists in the old Uyghur script, which was probably Semitic in origin. An Arabic script replaced it in the thirteenth century when the Uyghur converted to Islam. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

See XINJIANG Articles factsanddetails.com ; XINJIANG: GEOGRAPHY, PEOPLE, WEATHER AND TRANSPORT factsanddetails.com ; ALTAI REGION AND ALTAI PEOPLE factsanddetails.com ; TIEN SHAN MOUNTAINS: KHAN TENGRI, PIK POBEDY, CLIMBS AND HIKES factsanddetails.com ; NINGXIA factsanddetails.com ; GANSU PROVINCE factsanddetails.com ; NORTH CENTRAL CHINA Articles factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Familiar Strangers: A History of Muslims in Northwest China”by Jonathan N. Lipman Amazon.com; “Governing China's Multiethnic Frontiers” by Morris Rossabi Amazon.com “Securing China's Northwest Frontier” by David Tobin” Amazon.com; Islam: “Islam in China” by James Frankel Amazon.com; “Islam in China” by Mi Shoujiang, You Jia, et al. Amazon.com; “China and Islam: The Prophet, the Party, and Law (Cambridge Studies in Law and Society) by Matthew S. Erie Amazon.com ; Muslims “Ethnic Identity in China: The Making of a Muslim Minority Nationality” by Dru C. Gladney Amazon.com; “Ethnographies of Islam in China” by Rachel Harris, Guangtian Ha, et al. Amazon.com; “Muslim Chinese: Ethnic Nationalism in the People’s Republic (Harvard East Asian Monographs) by Dru C. Gladney Amazon.com; Xinjiang: “Xinjiang: China's Central Asia” by Jeremy Tredinnick Amazon.com; “Xinjiang and the Modern Chinese State” by Justin M. Jacobs Amazon.com “Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland” by S. Frederick Starr Amazon.com; Herders: “China's Last Nomads: History and Culture of China's Kazaks” by Linda Benson and Ingvar Svanberg Amazon.com; “Winter Pasture: One Woman's Journey with China's Kazakh Herders” by Li Juan, Nancy Wu, et al. Amazon.com

Minorities in Northwest China

Salar and Tibetans with a pet fox

Northwest China Ethnic Groups: (mostly Xinjiang and Gansu Province) (size ranking of China's 55 minorities, ethnic group: population in 2010, 2000 and 1990):

3) Hui: 10,586,087 (0.7943 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 9,828,126 in 2000; 8,602,978 in 1990.

5) Uyghur: 10,069,346 (0.7555 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 8,405,416 in 2000; 7,214,431 in 1990.

18) Kazakh: 1,462,588 (0.1097 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 1,251,023 in 2000; 1,111,718 in 1990.

22) Dongxiang: 621,500 (0.0466 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 513,826 in 2000; 373,872 in 1990.

29) Tu: 289,565 (0.0217 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 241,593 in 2000; 191,624 in 1990.

31) Xibe: 190,481 (0.0143 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 189,357 in 2000; 172,847 in 1990.

32) Kyrgyz: 186,708 (0.0140 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 160,875 in 2000; 141,549 in 1990.

35) Salar: 130,607 (0.0098 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 104,521 in 2000; 87,697 in 1990.

38) Tajik: 51,069 (0.0038 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 41,056 in 2000; 33,538 in 1990.

46) Baoan: 20,074 (0.0015 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 16,505 in 2000; 12,212 in 1990.

47) Russian: 15,393 (0.0012 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 15,631 in 2000; 13,504 in 1990.

48) Yugur: 14,378 (0.0011 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 13,747 in 2000; 12,297 in 1990.

49) Uzbek: 10,569 (0.0008 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 12,423 in 2000; 14,502 in 1990.

56) Tatars: 3,556 (0.0003 percent of China’s population) in 2010; 4,895 in 2000; 4,873 in 1990.

Ethnic Groups in Northwest China: See Separate Articles:

HUI MINORITY: NUMBERS, IDENTITY AND RELATIONS WITH CHINESE factsanddetails.com ;

HISTORY OF THE HUI AND HUI ISLAM factsanddetails.com ;

HUI LIFE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com ;

UYGHURS AND THEIR HISTORY, LANGUAGE AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com ;

UYGHUR LIFE, MARRIAGE, HOMES AND FOOD factsanddetails.com ;

UYGHUR CULTURE. LITERATURE, KNIVES AND HIP HOP factsanddetails.com ;

KAZAKHS IN CHINA: HISTORY AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com ;

KYRGYZ IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ;

TAJIKS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ;

UZBEKS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ;

DONGXIANG MINORITY factsanddetails.com ;

SALAR MINORITY factsanddetails.com ;

BONAN MINORITY factsanddetails.com ;

TATARS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

XIBE MINORITY factsanddetails.com

YUGUR MINORITY factsanddetails.com

Muslims in Northern and Western China

Islam reached China in the mid-seventh century through Arab and Persian merchants. The religion has a large following among ten of China’s minorities: Hui, Uyghur, Kazak, Tatar, Kyrgyz (Kirghiz), Tajik, Uzbek, Dongxiang, Salar, and Baoan. They live mostly in Xinjiang, Gansu, Ningxia, Yunnan, Qinghai, Inner Mongolia, Henan, Hubei, Shandong, Liaoning, Beijing, and Tianjin.

Nearly all Muslims in China belong to ethnic minority nationalities. Most are members of the Uyghur and Hui nationality people.. Islam is one of the officially sanctioned religions. Community-funded mosques, prayer rugs and even a few veiled women can been seen in the barren deserts and stony mountains of western China; the Silk Road cities such as Turfan, Kashgar and Khotan; and villages and towns in Ningxia Province and parts of Gansu Province and Inner Mongolia..

Ninety-nine percent of the Muslims in China are Sunnis. The other 1 percent are Shiites. Most of them are Tajiks. Many ordinary Chinese regard Islam as backward and oppressive. Muslim groups in China have traditionally not been very religious. Islam for them has been more of cultural badge than an ideology to live by. Although many Chinese Muslims don’t eat pork many drink alcohol and neglect their daily prayer duties. In some places in western China, Muslim women wear veils, not for religious reason, but to keep out the dust.

During the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) there were armed uprisings of Muslim ethnic and religious movements in Shaanxi and Gansu (1862-1875), and the “Panthay" Muslim Rebellion in Yunnan (1856-1873). Even after the status of Xinjiang was changed from a military colony to a province in 1884, Muslim resistance continued until the end of the dynasty. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

See Separate Article MUSLIMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Kazahks, Kyrgyz, Mongols and Uighurs

Kazakh traders at the China-Kazakhstan border

Kazahks, Kyrgyz, Mongols and Uighurs can easily communicate because their languages are so similar and often eat and party together. During social gatherings, women usually serve the meals but don't join the men while they are eating. They do join in for the after dinner sing and dancing.

Permanent Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Mongol and Uighur homes are made of mud bricks covered with smooth mud "plaster." Red and black carpets with geometric designs cover the walls and floors. Most homes have kangs, a raised platform with yet more rugs where family eats, relaxes and sleeps under a heap of quilts. Kangs are heated in the winter. Meals are usually cooked over an open fire on a mud brick stove formed in the corner of the house.

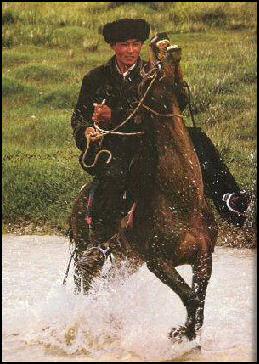

Horseman groups originated about 2,500 years ago and continue in various forms today. Throughout their long run they have maintained many of the customs, characteristics, martial arts and methods of organization that evolved millennia ago such spending living in yurt-style tents, drinking fermented mare’s milk, fighting from horseback and creating art forms that celebrate horses and animals of the steppe.The home range of the early horsemen, the Eurasia steppe, is vast area of land that extends from the Carpathian mountains in Hungary to eastern Mongolia.

See Separate Articles: MONGOLIANS IN CHINA: THEIR HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION, FESTIVALS factsanddetails.com MONGOLIAN LIFE AND CULTURE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Horsemen and Nomads of Xinjiang

About 40,000 ethic Kazakh, Mongol and Kyrgyz nomads still roaming the grasslands. Authorities want them to settle down in permanent houses and are attempting to do this by fencing off grazing grounds and establishing permanent settlements. The Chinese see nomadism as inferior to farming and conventional livestock rearing.

In places where overgrazing is a problem fences have been put up and herders have been given plots of land to encourage to take good care of it. To reduce the number of animals the government is encouraging herders to cut the size of their flocks by 40 percent, relocate and stall-feed their animals. But herders are not so keen on these ideas. Animals have traditionally been a source of wealth and a kind of insurance for hard times.

Some nomads like the idea. They want a high standard of living. Those that participate in the Chinese program are given 13 hectares of land, a four-room concrete house. One former nomad rents out three fourths of his land to a farmer who grows wheat and vegetables and cotton. With the rest of the land he grows food for his 200 sheep, 100 cows and 70 horses. Detractors argue the program will spoil ethnic identity and destroy the grasslands through overgrazing.

The Mongols, Turks, Huns, Tartars and Scythians are the best known of horsemen groups that have roamed the steppes of Central Asia and the ones that were most successfully expanding beyond their native realm and impacted the worlds they touched. The Mongols created the largest empire the world have ever known.

See Separate Article KAZAKHS IN CHINA: HISTORY AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com ; KYRGYZ IN CHINA: HISTORY AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com ; NOMADIC HERDERS IN CHINA AND EFFORTS THEM factsanddetails.com ;NOMAD LIFE factsanddetails.com ; NOMAD MIGRATIONS; factsanddetails.com HORSEMAN TENTS, FOOD AND DRINK factsanddetails.com MONGOL NOMADIC LIFE factsanddetails.com

Kazakh Nomadic Life

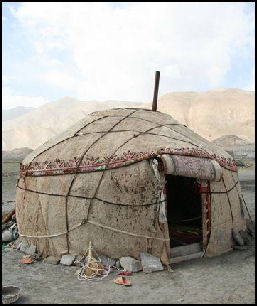

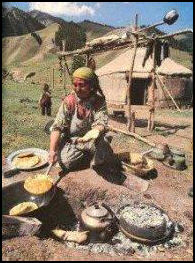

Animal skin yurt Except for a few settled farmers, most Kazakhs have traditionally lived by animal husbandry, migrating to look for pasturage as the seasons change. In spring, summer and autumn, they live in collapsible round yurts and in winter build flat-roofed earthen huts in the pastures. In the yurt, living and storage spaces are separated. The yurt door usually opens to the east, the two flanks are for sleeping berths and the center is for storing goods and saddles; in front are placed cushions for visitors. Riding and hunting gear, cooking utensils, provisions and baby animals are kept on both sides of the door. [Source: China.org |]

The pastoral Kazakhs live off their animals. They produce a great variety of dairy products. For instance, Nai Ge Da (milk dough) Nai Pi Zi (milk skin) and cheese. Butter is made from cow's and sheep's milk. They usually eat mutton stewed in water without salt – a kind of meat eaten with the hands. By custom, they slaughter animals in late autumn and cure the meat by smoking it for the winter. In spring and summer, when the animals are putting on weight and producing lots of milk, the Kazakh herdsmen put fresh horse milk in shaba (barrels made of horse hide) and mix it regularly until it ferments into the cloudy, sour horse milk wine, a favorite summer beverage for the local people. The richer herdsmen drink tea boiled with cow's or camel's milk, salt and butter. Rice and wheat flour confections also come in a great variety: Nang (baked cake), rice cooked with minced mutton and eaten with the hands, dough fried in sheep's fat, and flour sheets cooked with mutton. Their diet contains few vegetables. |

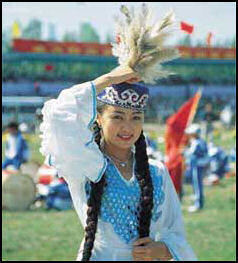

The Kazakhs migrate between the high pastures in the summer and the river valleys in the winter. The distance between pastures and the river valleys is often less than 50 miles. During the summer they often set up their yurts in the open pastures and gather for circumcision ceremonies, weddings, funerals, festivals and family reunions that often feature horse races and young girl dancers in beaded costumes. During the winter the Kazakhs and their animals live in mud-brick structures and the animals survive off fodder and any grass they can find. In the spring the Kazahks take their sheep to the low pastures, where the ewes give birth, and later they move to the higher summer pastures. According to a Kazak saying, "the snow leads the sheep."

The sheep generally drop their lambs at a birthing place in the summer pastures. Located next to the yurt, the birthing place consists of three-sided shelter and low fence, both made of flat rocks. After the lambs are born they are often brought into the yurt for the first couple of nights so the don't suffer from the cold.

Nomadic Kazakhs and the Chinese Government

Today, many Kazakhs live in apartments but use yurts for ceremonies. Others live in stone or mud-brick houses — with carpets on the floor, kilims on the walls, blackened by soot from the wood strove — in the winter and live in yurts in the summer. The roofs of the yurts of wealthy Kazakhs are often elaborately embroidered. To earn money nomadic Kazakhs sell mutton, lamb, wool and sheepskin from their sheep. Chinese merchants provide them with clothes, consumer items, sweet and particularly alcohol.

The Communist government is trying to encourage nomadic Kazakhs to settle down. The Chinese are helping former nomads build brick and concrete homes with electricity, television and other modern amenities. Settled Kazakhs still raise sheep and slaughter them by hand with a knife.

The Kazakhs resisted attempts to by the Communists to make them live on sheep-raising communes. About 60,000 Kazakhs reportedly fled to the Soviet Union in 1962 and other crossed the border in India and Pakistan or were granted political asylum in Turkey. Torgass Pass between Xinjiang, China and Soviet Kazakstan was closed in 1971 and not reopened until 1983.

See Separate Articles NOMADIC HERDERS IN CHINA AND EFFORTS THEM factsanddetails.com ; RESETTLED TIBETAN HERDERS factsanddetails.com TIBETAN HERDERS AND NOMADS factsanddetails.com

Kyrgyz Nomadic Lifestyle

Horses in Yiling region of XinjiangThe Kyrgyz material life is still closely related to animal husbandry; garments, food and dwellings all distinctively feature nomadism. The nomad Kyrgyz live on the plains near rivers in summer and move to mountain slopes with a sunny exposure in winter. The settled Kyrgyz mostly live in flat-roofed square mud houses with windows and skylights. The nomadic Kyrgyz of Kizilsu graze their livestock herds on low-lying grassland plains in the vicinity of rivers during the summer months, then relocate to higher mountain terrain during the winter, as the higher mountain slopes offer more exposure to the warming rays of the sun during winter.

The diet of the Kyrgyz herdsmen mainly consists of animal byproducts, with some cabbages, onions and potatoes. They drink goat's milk, yogurt and tea with milk and salt. Rich herdsmen mainly drink cow's milk and eat beef, mutton, horse and camel meat, wheat flour and rice. They store butter in dried sheep or cattle stomachs. All tableware is made of wood.

The tents are made of felt, generally square in shape, fenced around with red willow stakes. The tent frame is first covered with a mat of grass and then a felt covering with a one-meter-square skylight, to which a movable felt cover is attached. The tent is tied down with thick ropes to keep it steady in strong winds and snowstorms. Kyrgyz settlers, in contrast, live in flat-roofed square mud houses with windows and skylights, and make their living as farmers.

Kyrgyz and Horses

Horses are like wings for people of the steppe. Children learn to ride around the same time they begin to walk. Kyrgyz people are no exception. When Kyrgyz children are 7 or 8 years old, they must take horses as their partners and grasp all skills of riding and training them. Kyrgyz people regard horses as holy animals. They ride them, but they generally do not make them pull cart or do farm work or other tough jobs. They treat their precious horses as own family members. In addition to regularly feeding them and providing them with drink, Kyrgyz adorn them with lavish care. Saddles and stirrups are made of the best materials by superior craftsmen. Sometimes their saddles were worth more that their horses. In the old days, Kyrgyz men gave presents of gems and gold to their horses as well as their wives. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities]

Horses are prized as means of transportation, sources of food, investments and displays of wealth. People use them primarily to get around and herd sheep. They are bred and sold, milked and occasionally eaten. They are prized as sources of koumiss. Homemade horse sausages— said to be made from “the best part of the horse”— sells for about $3.25 a kilo. Even Kyrgyz who live in cities are expected to be excellent horsemen and have a horse and saddle back in their home villages. Manhood is often judged by horsemanship.

In addition to saddles, Kyrgyz people adorn their horses with various kinds of ornaments and clothes. Sometimes these cost more than its owner’s entire wardrobe. A horse’s appearance is regarded as a measure of status, economic level and skill of a housewife. Kyrgyz people think of horses as their close mates and confidants. When young men marry their wives, they must present their best horses to the wives' families; at the same time, brides must take their best horses to their new homes. Horses are viewed as precious gifts to present a good friend or seal a deal. ~

Kazakh and Kyrgyz Nomadic Customs and Taboos

The Kyrgyz are very hospitable and ceremonial. Any visitor, whether a friend or stranger, is invariably entertained with the best — mutton, sweet rice with cream and noodles with sliced mutton. Offering mutton from the sheep's head shows the highest respect for the guest. At the table, the guest is first offered the sheep tail fat, shoulder blade mutton and then the mutton from the head. The guest should in the meantime give some of what is offered back to the women and children at the dinner table as a sign of respect on the part of the visitor. Anyone who moves his tent is entertained by his old and new neighbors as tokens of farewell and welcome. [Source: China.org |]

The Kyrgyz are very hospitable and ceremonial. Any visitor, whether a friend or stranger, is invariably entertained with the best — mutton, sweet rice with cream and noodles with sliced mutton. Offering mutton from the sheep's head shows the highest respect for the guest. At the table, the guest is first offered the sheep tail fat, shoulder blade mutton and then the mutton from the head. The guest should in the meantime give some of what is offered back to the women and children at the dinner table as a sign of respect on the part of the visitor. Anyone who moves his tent is entertained by his old and new neighbors as tokens of farewell and welcome. [Source: China.org |]

Traditionally, when a guest came calling, the host invariably unsaddled the guest's horse, and when the guest expressed a desire to depart, the host saddled the guest's horse for him. When a family pulled up its tent stakes to move elsewhere — even if only to a nearby vacant space — the family was feted both by the old as well as the new neighbors. At the same time, Kyrgyz observe a few unyielding taboos: they abhor lying and cursing, and they have rules of etiquette that govern many aspects of social interaction, from how to address one another to where one may relieve oneself. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

The Kazakhs are warm-hearted, sincere and hospitable. They entertain all guests, invited and uninvited alike, with the best things they have — usually a prize sheep. At dinner, the host presents a dish of mutton with the sheep's head to the guest, who cuts a slice off the right cheek and puts it back on the plate as a gesture of appreciation. He then cuts off an ear and offers it to the youngest among those sitting round the dinner table. He then gives the sheep's head back to the host.[Source: China.org |]

The etiquette of the Kazakhs is defined by nomadic lives and Islamic religion. According to Chinatravel.com: “They attach much importance to the birth of new life. After a baby is born, they will hold a three-day celebration, which is called the cradle ceremony. Kazakhs respect the old. They will politely offer tea or meal firstly to the older people. Usually the elder members of the family are firstly seated and then the rest will be seated cross-legged or on knees around the table. The best meat is served to the elderly. When guests come to visit, the host will entertain them with the best foods. For highly honored guests or relatives that haven’t net for years, mutton and horse are entertained. Before eating, the host will firstly bring water, kettle and washbasin for the guest to wash their hands, and then serve the plate with sheep head, rear leg and rib meat in front of the guest. The guest should firstly cut out and eat a piece of meat from the sheep cheek and then the left ear, and give the sheep head to the host. Then every one can start eating together. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

There are lots of taboos in Kazakhs. The following are the main taboos. 1) It is forbidden to eat port, any animals that are not slaughtered or blood of any animal. 2) Animals are usually killed by male. 3) Don’t hold and eat the entire Nang (a kind of crusty pancake) when having meals. 4) It is not allowed to be seated on the bed when in a yurt; instead people should be seated on the floor mat with legs crossed instead of extending the legs. 5) Young people should not drink alcohol in front of old people. 6) When eating or talking with others, it is forbidden to pick noses or ears, spit, or yawn. \=/

7) When visiting, it is provocative or inauspicious if the guest comes rushing to the gate on horse. The guest should slow their horses’ running while approaching the gate. 8) It is considered to be defiant if the guest enters the yurt with horsewhip. 9) The guest should not be seated on the right side of the heating stove, which is the seat of the host. 10) They shouldn’t place food on wooden cabinets or on any daily living goods. The guest should follow the host’s lead. 11) When having meals or drinking milk tea, it is not allowed to stamp on the table cloth or walk over the table. Do not leave until the table is cleaned. 12) If the guest has an emergency and needs to leave, he or she should not walk in front of the host, but rather walk behind people. 13) When the hostess is preparing meals, the guest should not enter the kitchen or the place where food is preparing. 14) The guest should not fiddle with dinnerware or food, nor should they open the pot cover. 15) The guest should drink up the horse milk, and if they don’t drink alcohol, they should at least sip a bit showing gratitude, otherwise, the host will be unhappy. 16) Before and after meals, the host will pour water for the guest to wash hands. Do not slosh after washing hands; wipe hands dry using towels and politely return it to the host. 17) When it too late and if the host asks the guest to stay for the night, do not refuse to use the bedclothes of the host, otherwise the host will lose face. \=/

7) When visiting, it is provocative or inauspicious if the guest comes rushing to the gate on horse. The guest should slow their horses’ running while approaching the gate. 8) It is considered to be defiant if the guest enters the yurt with horsewhip. 9) The guest should not be seated on the right side of the heating stove, which is the seat of the host. 10) They shouldn’t place food on wooden cabinets or on any daily living goods. The guest should follow the host’s lead. 11) When having meals or drinking milk tea, it is not allowed to stamp on the table cloth or walk over the table. Do not leave until the table is cleaned. 12) If the guest has an emergency and needs to leave, he or she should not walk in front of the host, but rather walk behind people. 13) When the hostess is preparing meals, the guest should not enter the kitchen or the place where food is preparing. 14) The guest should not fiddle with dinnerware or food, nor should they open the pot cover. 15) The guest should drink up the horse milk, and if they don’t drink alcohol, they should at least sip a bit showing gratitude, otherwise, the host will be unhappy. 16) Before and after meals, the host will pour water for the guest to wash hands. Do not slosh after washing hands; wipe hands dry using towels and politely return it to the host. 17) When it too late and if the host asks the guest to stay for the night, do not refuse to use the bedclothes of the host, otherwise the host will lose face. \=/

See Separate Articles KAZAKH CUSTOMS, ETIQUETTE AND HOLIDAYS factsanddetails.com abd CUSTOMS AND ETIQUETTE IN KYRGYZSTAN factsanddetails.com

Kazakh Yurt

Nomadic Kazakhs have traditionally lived in yurts, circular white felt tents with broad conical roofs and flaps which are opened to let smoke from cooking and heating fires escape. A typical yurt is furnished with chests, tables, cooking stuff and other possession. Rugs cover the floor and people either sit on rugs or on low stools. Yurts are easy to disassemble and transport from place to place.

According to the historical records, Wusun people, the remote ancestors of the Kazakhs, dwelled in yurts. In 105 B.C., a Xijun princess, who married the King of Wusun people, Kunmo, wrote in Yellow Swan Song: "taking the sky as room and felt as wall, taking meat as food and jelly as thick liquid." The reference to felt walls is regarded as evidence that the Kazakhs have lived in yurts for more than 2000 years. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences ~]

Constructing a yurt

The entrance to the Kyrgyz yurt, or “akoi”, usually faces east and has a door made of pine or birch wood. Floors are lined with felt and covered by shrydaks and sometimes yak skins. They often have a cast iron stove in the middle used for heat, cooking and warming up tea. People stand-up or sit on carpets. Buckets and plastic bottles hang from the walls. Sometimes there are small cabinet used for storing utensils abd dishes. Some town dwellers still keep yurts outside their homes.

The exterior of the Kyrgyz yurt is made with several felt layers fastened by ropes. The inside is divided into two parts. The right side, is the “women’s side' (the eptchi zhak). This is the place for kitchen utensils and dish-washing. Thread, needles, needle-work, knitting and all sorts of females articles are kept in bags on this side. The left side is the “male side” (er zhak). Here one can find saddlery, kumchas (whips), knives for hunting and tools used for cattle-breeding, handicrafts and hunting. There also is an ample supply of carpets, juk blankets, pillows, heaped-up on special places of rest. [Source: kyrgyz.net.my, official Kyrgyzstan tourism website]

See KAZAKH NOMADIC LIFE AND YURTS factsanddetails.com ; NOMADIC LIFE AND YURTS IN KYRGYZSTAN factsanddetails.com GERS (YURTS): STEPPE HORSEMAN TENTS factsanddetails.com and LIFE IN A GER (YURT) factsanddetails.com

Nomadism in China and Art

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: The Mongolian, Tibetan, and western Muslim people living in western, southern and northern China and the Eurasian continent share many things in common, including and high terrain and the cold climate, with unpredictable rainfall, in which they live, and the traditional nomadic lifestyle. Except for settlements along river valleys and oases, a nomadic economy has traditionally governed the way of life there. This lifestyle also explains why people living over such a vast area share commonalities in their material culture and art forms. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei]

Nomadism is a lifestyle chosen in response to the natural conditions of the place where they live and usually involving the optimal use of limited resources. Following the customs and experiences they inherited, nomads move with their animals in keeping with the seasons. Livestock, such as horses, cattle, and sheep, is important to them, providing clothing, food, and transportation. Every part of the plants they encounter along the way is also utilized to make many of the things needed in life. These people often live in tent-like structures easy to erect and take apart, as vessels for food and drink are taken with them and not much else. Such basic necessities of life as wooden bowls and utensils, when given as presents, reflect their simple and practical values. The workmanship involved in such objects, however, is elegantly refined, amply demonstrating the maturity of arts and crafts among these nomads.

Gold aigrette with pearl and gem inlay

The western Muslim regions of China are located at the confluence of Europe and Asia, being home to ethnically and linguistically diverse groups of peoples, including Kazakhs, Tajiks, Uzbeks, and Uyghurs all co-existing at the same time. Located at a vital point along the Silk Route, it was a place where Mediterranean, Islamic, and Indian cultures converged by means of trade and commerce over an extended period of time. Both the movement of peoples and circulation of their art techniques enjoyed free passage in this region transcending borders, forming a mix of cultures. In the Yuan dynasty, the Mongols were able to connect the great civilizations of East and West, and later the Manchu in the Qing dynasty assumed control over Inner Asia, reopening this passage in the west once more. Consequently, the delicate metal wares of nomadic peoples and the aesthetics of Islamic jades and precious stones appeared as far away as the Forbidden City in Beijing, injecting Qing dynasty art with new vitality. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Gold aigrette with pearl and gem inlay is a 19th century work of the Muslim regions or the Mughal Empire at the National Palace Museum. According to the museum: This magnificent accessoryis a clear embodiment of Islamic culture. The artifact holds numerous thin, long golden branches that extend outwards from the central column. The top of the column is a pink tourmaline featuring a design that is reminiscent of the cluster of upright feather tassels found on kings' headscarves in Islamic culture post-eighteenth century. In addition, the beads and red and green gemstones embedded on the central column demonstrate colors, aesthetics, and inlay and string decoration techniques that mirror those of the Mughal Empire. The Islamic-styled headdresses found in the collection of the Qing court may have been offered by Altishahr, a region comprising the Tarim Basin as well as the Southern Circuits of Tian Shan at the time. The said region includes modern-day Afghanistan and a part of Kyrgyzstan. In the early nineteenth century, merchants of the Khanate of Kokand controlled the import and export trades of Central Asia as well as those of Northern and Southern Circuits of Tian Shan. Because of geographical vicinity and cultural similarity, Islamic culture-related artifacts were remarkably common in Altishahr at the time, contributing to some of its artifact masterpieces being subsequently sent to the Qing court.

Xinjiang-Set Fiction by Jueluo Kanglin

In the early 2010s, thrillers and mysteries connected to Tibet were all the rage in China. Bruce Humes wrote in Altaic Storytelling: “But Tibet is certainly not the only area of the People’s Republic rich in non-Han culture and history with strong potential for such fiction. Two novels by former journalist Jueluo Kanglin), including the newly launched (literally, The Mysterious Realm of Lop Nur), are bound to raise Xinjiang’s profile among aficionados of the “exploration thriller” genre. [Source: Bruce Humes,Altaic Storytelling, May 18, 2014]

“As a site engendering curiosity and even fascination, Lop Nur’s credentials are impeccable and ancient: archaeologists unearthed the (controversial) Tarim mummies along the lake (Lop Nur means “Lop lake”); explorers such as Marco Polo, Ferdinand von Richthofen, Nikolai Przhevalsky, Sven Hedin and Aurel Stein all set foot in the area; and more recently, Chinese scientist Peng Jiamu disappeared there (1980), and Chinese explorer Yu Chunshun died trying to walk across Lop Nur (1996).

Jueluo Kanglin, the author of The Mysterious Realm of Lop Nur and Curse of Kanas Lake, is a member of the Xibe ethnicity born in Xinjiang’s Yili, and reportedly speaks Xibe as well as several Turkic languages, including Uyghur, Kazakh and Kyrgyz.

“Curse of Kanas Lake, published in 2012, highlights legends of the Tuvan people surrounding this beautiful lake (now a preserve) which is located in Altay Prefecture where Xinjiang borders on Kazakhstan, Mongolia and Russia. The tale takes place in modern Kanas. A petroglyph uncovered by a flood is taken away by an anthropologist — ostensibly for research — but eventually treated as a money-making oddity that is exhibited in a museum. But the local elders are very disturbed by this, and the Shamaness believes that the slab is inhabited by the spirit of an ancient folk hero. Removing the stone slab from its natural environment disturbs the natural order of things, and presages a series of disasters.

See Separate Article XIBE MINORITY factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Noll site, National Palace Museum Taipei

Text Sources: 1) "Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China", edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K.Hall & Company, 1994); 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China *\; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2022