CHINESE TEENAGERS

In the 2000s, teenagers were reaching puberty about a year earlier than they did in the 1980s, in some cases before they were 11. In East Asia, according to one study in the 2000s, teenagers socialize less than one hour a day, compared to 2 to 3 hours in North America. Many lack social skills to deal with a increasingly competitive world. One study found that 45 percent of Chinese urban residents are at risk to health problems due to stress, with the highest rates among high school students.

In the 2000s, teenagers were reaching puberty about a year earlier than they did in the 1980s, in some cases before they were 11. In East Asia, according to one study in the 2000s, teenagers socialize less than one hour a day, compared to 2 to 3 hours in North America. Many lack social skills to deal with a increasingly competitive world. One study found that 45 percent of Chinese urban residents are at risk to health problems due to stress, with the highest rates among high school students.

Most Chinese teenagers have computers, smart phones and are very Westernized and active online. One young urban woman told the International Herald Tribune in the early 2000s, “Kids now have computers, surf the Internet and watch different types of television programs. From a young age they are exposed to the outside world.” . Still traditional values endure. On her hopes and dreams one 17-year-old girl told the New York Times, “As long as I study hard and love my parents, I’m quite content with what I have. My mother’s expectations are high. She wants me to grow into a person of talent and education, with manners and a career.”

Hsiang-ming kung wrote in the “International Encyclopedia of Marriage and Family”: “Extensive school attendance and nonfamily employment have set the youth free from absolute parental authority and much family responsibility. Teenage subcultures have emerged as well. Although the relationship between parents and children has become a more equal and relaxed one, Chinese parents still emphasize training and discipline in addition to care taking (Chao 1994). [Source: Hsiang-ming kung, “International Encyclopedia of Marriage and Family”, Gale Group Inc., 2003]

Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner wrote in “CultureShock! China”: In Young & Rubicam’s Brand Asset Valuator study published in 2005, Chinese youths were more aspirational than their Japanese or American counterparts, but they continued to hold the traditional value of filial piety just as strongly as their ancestors had. In China, there is one sure way to get ahead and that is through education. The government has done an excellent job identifying the best and the brightest, no matter what remote part of China they live in.[Source: “CultureShock! China: A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette” by Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner, Marshall Cavendish 2011]

Some teenagers and people in their early 20s in places like Shenzhen are regarded as wasted youth, The work at odd commercial jobs in the day and hang out nightclubs, drop ecstasy and have casual sex at night. In the 2000s, Newsweek described on young man who liked to hire prostitutes to perform oral sex on him while he raced around in his car on Shenzhen's highways.

Population 14 and under:18 percent (compared to 39 percent in Kenya, 18 percent in the United States and 12 percent in Japan). [Source: World Bank data.worldbank.org ]

See Separate Articles: CHINESE YOUTH AND "LYING FLAT" factsanddetails.com ; LITTLE EMPERORS AND MIDDLE CLASS KIDS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; ONE-CHILD POLICY factsanddetails.com ; SERIOUS PROBLEMS WITH THE ONE-CHILD POLICY: factsanddetails.com ; FAMILIES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; DIFFICULTY FINDING A JOB AFTER UNIVERSITY IN CHINA AND THE GOVERNMENT RESPONSE TO IT factsanddetails.com; RESPONSE OF CHINESE GRADUATES TO THE DIFFICULTY FINDING A JOB factsanddetails.com; SINGLE ADULTS AND LEFTOVER WOMEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SINGLE MOTHERS, MARRIED WITH NO CHILDREN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE WOMEN factsanddetails.com ; CHILDREN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SEX RATIO, PREFERENCE FOR BOYS AND MISSING GIRLS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ;

Teenage Boys in 19th Century China

In 1899, Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Village Life in China”:“In theory a Chinese lad becomes of age at sixteen, but as a practical thing he is not his own master while any of the generation above him within the five degrees of relationship remain on the mundane stage. To what extent these relatives will carry their interference with his affairs, will depend to a large extent upon their disposition, and to some extent upon his own. In some households there is a great amount of freedom, while in others life is a weariness and an incessant vexation because Chinese social arrangements effectually thwart Nature’s design in giving each human being a separate personality, which in China is too often simply merged in the common stock, leaving a man a free agent only in name. [Source: “Village Life in China” by Arthur Henderson Smith, Fleming H. Revell Company, 1899, The Project Gutenberg; Smith (1845 -1932) was an American missionary who spent 54 years in China. In the 1920s, “Chinese Characteristics” was still the most widely read book on China among foreign residents there. He spent much of his time in Pangzhuang,a village in Shandong.]

“Taking it in an all around survey there is very little in the life of the village boy to excite one’s envy. As we have already seen, he generally learns well two valuable lessons, and the thoroughness with which they are mastered does much to atone for the great defects of his training in other regards. He learns obedience and respect for authority, and he learns to be industrious. In most cases, the latter quality is the condition of his continued existence and those who refuse to submit to the inexorable law, are disposed of by that law, to the great advantage of the survivors. But of intellectual independence, he has not the faintest conception or even a capacity of comprehension. He does as others do, and neither knows nor can imagine any other way. If he is educated, his mind is like a subsoil pipe, filled with all the drainage which has ever run through the ground. A part of this drainage originally came, it is true, from the skies, but it has been considerably altered in its constituents since that time; and a much larger part is a wholly human secretion, painfully lacking in chemical purity. In any case this is the content of his mind, and it is all of its content.

“If, on the other hand, the Chinese youth is uneducated, his mind is like an open ditch, partly vacant, and partly full of whatever is flowing or blowing over the surface. He is not indeed destitute of humility; in fact he has a most depressing amount of it. He knows that he knows nothing, that he never did, never shall, never can know anything, and also that it makes very little difference what he knows. He has a blind respect for learning, but no idea of gathering any crumbs thereof for himself. The long, broad, black and hopeless shadow of practical Confucianism is over him. It means a high degree of intellectual cultivation for the few, who are necessarily narrow and often bigoted, and for the many it means a lifetime of intellectual stagnation.

Youth Culture in China in the Early 2010s

Pop culture researcher Jeroen de Kloet wrote: “In a country that seems particularly keen to periodise, these developments have given birth to yet another term for a generation conveniently classified by a decade: the 1980s (“balinghou”). This new generation of “little emperors,” as they are often cynically referred to, all come from one-child families, born after the Cultural Revolution. For them, China has always been a country which is opening up, a place of rapid economic progress and modernization, a place of prosperity and increased abundance, in particular in the urban areas. For this generation, “June 4th” — the term commonly used to refer to the Tiananmen student demonstrations of 1989 — is an event of a long forgotten past, if they remember it at all. The Chinese Communist Party is a tool for networking; becoming a member facilitates one’s career. Different labels are used, besides balinghou, for this generation, like “linglei” (“alternative”), “the birds” nest generation,” and the “zhongnanhai generation,” named after a cigarette brand name. Zhongnanhai — also the central headquarters of the Chinese Communist Party, close to the Forbidden City — is the song title of one track by Carsick Cars. [Source: Jeroen de Kloet, Danwei.org, June 11, 2010, Jeroen de Kloet is the author of “China with a Cut”, which looks into dakou culture and then the ensuing commercialism of China's music market.

On changes that have occurred in China, the writer Yu Hua wrote: “More than 30 years ago … boys and girls didn’t speak to each other at middle school… today, we even have girls going to the hospital for an abortion while wearing their school uniform. What has made us go from one extreme to another?” [Source: Xu Ming, Global Times, April 9, 2015]

On Youth in China today, Zhang Shouwang, lead singer of the Beijing rock group Carsick Cars, told Micheal Pettis in Esquire magazine: “I think one thing we all have in common is that there is such a huge gap in our experiences and understanding compared to Chinese who are in their mid-thirties or older. It seems that we live in very different worlds. More and more of us are exploring new ways of thinking and living, and I see this even more for young people who are four or five years younger than me.” [Source:Michael Pettis, Danwei.org, May 11, 2009. Pettis is finance professor at Peking University, China Financial Markets blogger, and owner of live music venue D22 in Wudaokou, Beijing.

Zhang Shouwang also said, “I think many of us feel that much of what we learned in school and in the media was not really true, or perhaps didn’t really fit our lives, and so we are reading books, listening to music, and sharing ideas that are very different from what we had been given. I think very few of our generation have beliefs the way older Chinese do. We believe in real things, and we find it hard to take seriously all the big, empty ideas that we were given.

Yang Haisong of the punk band P.K.14 told the Telegraph, “The youth culture in China was never mainstream, you can't even say it's a counter-culture, in fact we have no youth culture, because everyone is subject to the media and external influences — they do not have their own point of view,” he says.

Chinese Youth Culture and Activities

Chinese kawaii

The London and Hong Kong-based brand consultancy, Hunt Haggarty produced a report in 2009 that today’s youth have few ties with Mao era and they are more likely to find solidarity with friends than family and have rising self-confidence, tinged with a new cultural nationalism.

Source, a Shanghai-based lifestyle clothing brand with gallery dedicated to street life, tries to sum up a nascent new Chinese individualism as “there are those who find a need to live their lives the way they want, to express themselves, to have their own identityour ideals are simple — the right to choose the right to be unique.”

In the late 2000s it became kind of popular for some young people who didn’t know each to meet one another over the Internet and get together in real life in a place they were unfamiliar with. Described as “shan wan” (“lightning play”), the networking technique was typically employed by young adults when they went to a new city and wanted some companionship. In typical cases couples or small groups of four or five met and went on outings such as sightseeing or singing at karaoke, paying dutch as they went. Some participants didn’t use their real name and said they found the idea of spending the day with strangers stimulating, saying they could open and express themselves more freely than they could with people they know. [Source: Straight Times]

Youth Problems in China

Psychological problems are on the rise among young people. According to one survey, 30 million teenagers under 17 have mental problems. In April 2004 a Chinese health official said, “Psychological and mental problems among juveniles have become prominent as the country is changing fast into a modern society and mental illness becomes the top disease” of “Chinese teenagers.”

The government is trying to address “youth problems” by banning the release of new foreign films during school holidays, closing down Internet sites, racy magazines, text messaging aimed at teens and building “Youth Palaces” — party community centers that provide a dose of party propaganda along with sports and activities.

So far government efforts have born little fruit. The head of a Chinese marketing firm told the Los Angeles Times, “The party is trying to do a little updating and repackaging. But compared to campaigns by professional ad people, they still fall short. Most people would rather watch videos.”

See Juvenile Crime, Crime, Government

China's Obese Teens

Chinese teenager Zhu Lindai used to weigh 152 kilogrammes (335 pounds). "I used to stuff myself with hamburgers, crisps, doughnuts and buns. I ate too much," admits the 15-year-old, who withdrew from school to devote herself to slimming down. [Source: Sebastien Blanc, AFP , December 7, 2011]

Authorities said in September 2011 that obesity had become a major public health issue for China's children. Around one in five young urban Chinese is now overweight, according to market research firm QF Information Consulting. "There are two main reasons for childhood obesity: consuming too many calories and a lack of physical activity," Jia Jianbin, secretary general of the Chinese Nutrition Society, told AFP. "For example, the recommended consumption of oil per person is between 25 and 30 grammes (around one ounce) per day. In Beijing, people are eating on average at least 50 grammes a day," he said. "At the same time, people are not exercising enough. They drive to work, and at the weekend, they stay home and relax, watch television or surf the Internet."

Sha Zhiyu, who has taken a break from her education in the northern province of Shaanxi to attend weight-loss classed is a classic example. "Before, I was really into computer games. After meals I would sit for ages in front of my computer and play them. Then when I got tired I'd go to bed," the 17-year-old Sha told AFP. "I never did any exercise and I just kept putting on weight." The problem has been exacerbated by China's one-child policy, which has resulted in hundreds of millions of only children who are known as "little emperors" because they are often pampered by their parents. Many Chinese parents are also keen for their children to experience the luxuries they were denied under the country's former leader Mao Zedong.

The GYD centre in Beijing is dedicated to helping obese adolescents lose weight. A 42-day residential course that oversees eating and exercising cost 16,800 yuan (around $2,600). Zhu Lindai has shed nearly 50 kilos at GYD. Sha Zhiyu went from 139 to 114 kilos during the course. Under the supervision of an instructor, Zhu exercised for two hours every morning and afternoon with an optional extra hour in the evening, following a strict regime of running, pilates, group gymnastics, push-ups and sit-ups.

"People come here for various reasons," says Peng Tianci, the manager of GYD. "Some do not feel desirable in their personal relationships, while Dedicated slimming centres have sprung up across China over the past decade to take advantage of soaring obesity rates, as newly wealthy young Chinese swap rice bowls for burgers and bicycles for cars. GYD opened less than two years ago and already, people come from all over China to attend its courses. GYD's main competitor in Beijing, Bodyworks, says it has counted 50,000 clients since it opened in 2002. others are suffering from image problems at work, or believe their appearance will prevent them from getting a job. But the most common concern is health." At GYD, the fight-back starts with the daily menu. "Here, we avoid calorie-rich foods. We mostly serve high-fibre vegetables and fruit," says founder Gu Yudong as he sits surrounded by young diners in the GYD restaurant. After a brief pause to digest their dessert-free lunch, the teenagers head back to the gymnasium.

Young Adults in China

Many unmarried people in their 30s still live with their parents. Traditionally, living at home until one was married has been the norm in China. Chen Xinxi, a researcher at the National Women’s Association, told the Los Angeles Times: “In the U.S. when kids become 18 their parents consider them adults and shoo them out of the house, In China, parents of single children don’t want them to leave home, no matter how old they are.”

The incomes of 20 to 29 year olds rose 34 percent between 2004 and 2007 — faster than any other group. These young adults are the children of the one-child policy: a group that grew up spoiled and isolated and has responded by becoming obsessed with consumerism, the Internet and video games. Many work hard and party hard, take international trips to places like Egypt and Hawaii and have theme parties on Christmas and Halloween.

My wife teaches Chinese exchange students at a university in Japan. She said that many of her students — who grew up in China the one-child policy, Little Emperors era — have difficulty negotiating and coming to an agreement as a group. She attributes this to growing up without brothers and sisters. Many spent a lot of time on their own. One single child told the Los Angeles Times, “We grew up alone. I like to watch movies on my PC, alone in my room, where I can cry if I want to.”

There is a lot of diversity among young adults in China as is to e expected. On one hand you have "Liuman", an untranslatable term that roughly mean loafer, hoodlum, hobo, bum and punk. On the other hand it is not uncommon to find company bosses who drive around in $100,000 BMWs and are their mid or late 20s. One 28-year-old Chinese woman told The New Yorker, “In my generation, there’s a lot of desperation to be different, to be individual. Because we are only children, we grew up the center of attention in our families and now we want the attention of society.”

National Geographic photographer David Butow, the creator of a photographic journal of China’s young people wrote: “The young are living with an almost boundless sense of possibility in China, and with some equally large anxieties, You see it most in the big cities...The government encourages individual ambition , as long as it doesn’t run afoul of the central plan. But there are few role models for young people to emulate. A 25-year-old can’t follow in the footsteps of a 45-year-old. The paths that the older person took are no longer on the map.”

See Children, Little Emperors

Selfish Young Adults in China

The “post-80s” generations refers to people under 30 who have grown up long after the Mao period was over and have only known relative economic growth and prosperity. Surveys show members of this group are more interested in personal “identity” than traditional “harmony. Psychiatrist Li Zhongyu complained to the China Daily, “This generation is spoiled. They don’t know what responsibility is.”

The one-child policy has produced a generation of self-centered young adults who have an exaggerated sense of entitlement and are unable to sustain relationships. There are cases of marriages falling apart after months or even weeks, with some couples breaking it off so they can spend more time with their lovers. In some cities one third of all divorces involve young adults from the one-child policy generation. Prof. Fucius Yunlan, a U.S. trained psychiatrist, told Reuters, “They are weak in horizontal bonding, communicating with the same generation. They attend to apply a vertical approach to horizontal relationships.”

Ambition and hedonism are increasingly characterizing today’s young adults. One university student told National Geographic, "I'm going to use my brains to get ahead. I'm thinking about leaving the country some day. I like Western culture because it seems more natural." When one girl was asked by National Geographic what young people in Beijing want, she replied, "To get on the Internet, to play sports, to dance at discos.”

Urban young adults are surprisingly apolitical. One young account executive for the foreign advertising firm Ogilvy and Mather told Time, “There’s nothing we can do about politics. So there’s no point in talking about or getting involved. Events like the Cultural Revolution and the Great Leap Forward are viewed as ancient history. Some even regard the crackdown at Tiananmen Square as something “certainly needed.” On young woman told Time. “Our life is pretty good. I care about my rights when it comes to the quality of a waitress in a restaurant or a product I buy. But when it comes to democracy and all that, well...That doesn’t play a role in my life.”

The one-child policy has also resulted in a lot of nerds. One university student told the Washington Post, “Most young people my age have only focused on their studies since childhood. We are relatively delicate and fragile.”

Cultural Revolution Generation on the Consumer Revolution Generation

One young middle-class woman told The New Yorker,”Most of my generation has a smooth, happy life, including me. I feel like our character lacks something. For example, love for the country or the perseverance you get from conquering hardships. Those virtues, I don’t see them in myself and many people my age.” A teacher in her 30s in the late 2000s told Peter Hessler in a National Geographic article, “When we were students there wasn’t a generation gap with the teachers. Nowadays our students have their own viewpoints and ideas. And they speak about democracy and freedom, independence and rights. I think we fear them instead of them fearing us.” Another said, “We had a pure childhood. But now the students are different, they are more influenced by modern things, even sex, But when we were young, sex was a taboo for us.”

In 2010, Alec Ash of China Beat interviewed professors Zhang Weiying and Pan Wei of Peking University (known as “Beida”) to see what people who grew up in the Cultural Revolution thought of young people today growing up in single-child families at a time of rampant consumerism and quest for money. [ Source: Alec Ash, China Beat, July 13, 2010]

Prof. Zhang Weiying, who is at the forefront of the “New Right” and helped to pioneer economic reforms in China in the early 80s, was asked what he thinks of Beida’s elite students, China’s future? No, of course there are bright sparks of independent thought (especially amongst his own students, of course). But in the “post 80s” generation as a whole, there is a worrying trend towards ziwozhongxin — self-centeredness. As the first generation of single children (the one-child policy came into effect in 1979), they take everything for granted.

One upshot of this, especially for the “post 90s” kids who are not used to hardship (like the generation young during the 60s and 70s are), is that the pressure gets on top of them when they enter university or working life. Professor Zhang pointed to the spate of Foxconn suicides — all young workers who had joined the company just months before — as an example.

Pan Wei is on the other side of the political spectrum, the “New Left”. He took his PhD at Berkeley, but back in China he was firmly of the opinion that China should follow its own path, not the West’s. A big problem at Beida he said was the declining number of students from the countryside. According to him, 70 percent of PKU’s students were from rural areas in the 1950s. 60-70 percent in the 60s. Today, the number is less than 1 percent. I can’t check that figure — Chinese universities are secretive about figures which would be public in Britain — but the trend itself is certainly incontestable.

Onto youth. Professor Pan echoed much of what Professor Zhang said. Young Chinese, single children and without the history and suffering of his generation, become weak. The same memes of individualistic and psychologically vulnerable came up. Also an astute comment, I think: that, on the whole, they aren’t interested in their parents’ history (more so in their grandparents”). But you could rephrase: the problem is that parents aren’t interesting in relating their history to their children.

Another result of their upbringing, Professor Pan told me, was nanxing de nuxinghua — boys becoming more like girls (or at least zhongxinghua — their neuterization). A boy who is loved excessively (ni ai) can’t fight for himself. At this point, he declared that this results in more homosexuals. This, I should say, was delivered in the spirit of observation not prejudice. I see no factual basis for it.

2007 Midi Music Festival

Young People and Politics in China

On attitudes toward Tiananmen Square, well-known editor Li Datong, “The current young generation turns a blind eye to it. I’ve never seen them respond to those domestic issues. Rather, they take a utilitarian, opportunistic approach.” Hessler found that few of the people in their 20s and 30s that he knew worried about politics, the environment or foreign affairs, they were more concerned about paying off loans for an apartment, earning more money and finding a spouse. The founder of a software firm who received a PhD in the United States told the Washington Post, “I have struggled to win my piece in China. I want t protect it. I don’t want a revolution anymore.”

For teenagers born after Tiananmen Square massacre, the Cultural Revolution seems like distant history, as remote as the Opium Wars or the Tang Dynasty. But this is not true with parents who often push their children very hard to succeed because they belong to the “tragic generation” that had the prime of their life stolen by the Cultural Revolution. At the same age their parents were working in fields and had next to nothing to eat modern children are enjoying computers, cell phones, English classes and trips abroad. The children of parents who had their “golden years” are sometimes referred to as the “Coddled Generation.”

Qi Ge wrote in Foreign Policy: “Ever since the 1970s, I have known that the Chinese people are the freest and most democratic people in the world. Each year at my elementary school in Shanghai, the teachers mentioned this fact repeatedly in ethics and politics classes. Our textbooks, feigning innocence, asked us if freedom and democracy in capitalist countries could really be what they proclaimed it to be. Then there would be all kinds of strange logic and unsourced examples, but because I always counted silently to myself in those classes instead of paying attention, the government's project was basically wasted on me. By secondary school and college, my mind was unusually hard to brainwash. [Source: Qi Ge, Foreign Policy, September 21, 2012]

Frustrations of China’s Generation Z

Li Yuan wrote in the New York Times: ““Chinese technology workers are often expected to work 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. six days a week, a practice so common that they call it “996.” Mr. Du’s schedule was worse. After he slept only five hours over three days late last year, his heart raced, he was short of breath and he grew sluggish. He quit shortly after. He hasn’t looked for a job in three months and seldom ventures outside. A doctor diagnosed mild depression. “Most of my peers I know still want to succeed, ” Mr. Du said. “We’re simply against exploitation and meaningless striving.” [Source: Li Yuan, New York Times, July 8, 2021]

“Nominally a socialist country, China is one of the world’s most unequal. Some 600 million Chinese, or 43 percent of the population, earn a monthly income of only about $150. Many young people believe they can’t break into the middle class or outearn their parents. The lack of upward social mobility has made them question the purity of the party, which they believe is too tolerant of the capitalist class.

“Many say their biggest enemies are the capitalists who exploit them. The biggest target of their ire is Jack Ma, the co-founder of the Alibaba e-commerce empire. He was once cheered as the embodiment of the Chinese dream. Now they jeer at his comments supporting the 996 work culture and saying business itself is the biggest philanthropy. “Workers are only moneymaking tools for people like him, ” said Xu Yang, 19, who went as far as to say people like Mr. Ma “need to be eliminated physically and spiritually.” Mr. Ma later walked back his remarks, saying he wanted only to pay tribute to workers who put in long hours out of love for their jobs.

China's Youth Embrace the 'Diaosi' ('Loser') Identity

Wu Nan wrote in the South China Morning Post, “When a large Diaosi billboard appeared in New York's Times Square in 2013 advertising the new online game, onlookers who know the meaning of the Chinese words were surprised. Diaosi, which has a crude translation, was originally used to curse someone as a loser. But the phrase has gone mainstream since 2011 and is widely used by young Chinese as a trendy way to describe and poke fun at their own low status. [Source: Wu Nan, South China Morning Post, May 10, 2013 \^]

“An estimated 526 million identify with the term, or 40 percent of the Chinese population, said a survey recently released by online game developer Giant Interactive Group and yiguan.cn, an IT market analysis website. The survey reflects the rise of a particular generation mostly born in the post-1980s and just starting their careers. They largely live on online, where they are able to unleash their frustrations and play out fantasy scenarios. In real life, their diaosi identity is worn as a badge of honour, especially for those who have made it big.\^\

“According to the recent survey, these youths are eager to improve their lives financially and personally. On average, they earn 6,000 yuan a month; two-thirds of them are single; and more than 94 percent spend long hours online, shopping for products and otherwise killing time so they are not so lonely.”\^\

“Online fiction writer, Geng Xin, based in Zhengzhou city in central China's Henan province, said diaosi were more cynics than dreamers. In Geng’s eyes, they talk more than they act. They don’t have bigger life goals. When they are not eating or working, they are online, reading fantasy fiction or playing video games. He compares diaosi with the Chinese Everyman, who can be found in literature, such as Wei Xiaobao in Jin Yong's The Deer and the Cauldron and Ah Q in Lu Xun's The True Story of Ah Q. \^\

“"I’m one of the diaosi," said Lin Hai. "We are common Chinese who are fighting for our dreams." Lin, 31, a popular online novelist, said their dreams were practical: buying a house and getting married. Even if prospects at attaining their goals are low, diaosi can always find a way - "even if it is in a virtual world", he said. [Source: Wu Nan, South China Morning Post, May 10, 2013 \^]

AK47 Playing in Xian

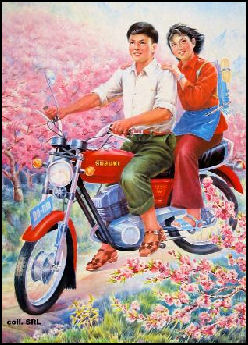

Image Sources: 1) Posters,Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/ ; 2) Family photos, Beifan.com ; 3) 19th century men, Universty of Washington; Wiki Commons; Asia Obscura

Chinese Youth and "Lying Flat"

In the early 2020s, a relatively small but visible group of Chinese urban professionals began drawing attention by choosing to "lie flat" ("tangping") and reject grueling careers to pursue what they called a "low-desire life." “"Only by lying down can humans become the measure of all things, " argued the "lying flat" manifesto. Cheryl Teh wrote in Business Insider: “It's a mindset, a lifestyle, and a personal choice for some disillusioned Chinese youth who have given up on the rat race and are staging a quiet rebellion against the trials of 9-9-6 work culture (See Below). The idea of "lying flat" is widely acknowledged as a mass societal response to "neijuan" (or involution). "Neijuan" became a term commonly used to describe the hyper-competitive lifestyle in China, where life is likened to a zero-sum game. [Source: Cheryl Teh, Business Insider, June 8, 2021 ==]

He Huifeng and Tracy Qu wrote in the South China Morning Post: “The movement’s roots can be traced back to an obscure internet post called “lying flat is justice”, in which a user called Kind-Hearted Traveller combined references to Greek philosophers with his experience living on 200 yuan (US$31) a month, two meals a day and not working for two years. “I can just sleep in my barrel enjoying a sunbath like Diogenes, or live in a cave like Heraclitus and think about ‘Logos’, ” the person wrote. “Since there has never really been a trend of thought that exalts human subjectivity in this land, I can create it for myself. Lying down is my wise man movement.” According to the anonymous poster, this humble existence left them physically healthy and mentally free. [Source: He Huifeng and Tracy Qu, South China Morning Post, June 9, 2021]

Xiang Biao, a professor of social anthropology at Oxford University who focuses on Chinese society, called tangping culture a turning point for China. “Young people feel a kind of pressure that they cannot explain and they feel that promises were broken, ” he told the New York Times. “People realize that material betterment is no longer the single most important source of meaning in life.” [Source: Elsie Chen, New York Times, July 3, 2021]

See Separate Article CHINESE YOUTH AND "LYING FLAT" factsanddetails.com

China’s Bitter Youths Embrace Mao

Li Yuan wrote in the New York Times: “They read him in libraries and on subways. They organized online book clubs devoted to his works. They uploaded hours of audio and video, spreading the gospel of his revolutionary thinking. Chairman Mao is making a comeback among China’s Generation Z. The Communist Party’s supreme leader, whose decades of nonstop political campaigns cost millions of lives, is inspiring and comforting disaffected people born long after his death in 1976. To them, Mao Zedong is a hero who speaks to their despair as struggling nobodies. In a modern China grappling with widening social inequality, Mao’s words provide justification for the anger many young people feel toward a business class they see as exploitative. They want to follow in his footsteps and change Chinese society — and some have even talked about violence against the capitalist class if necessary. [Source: Li Yuan, New York Times, July 8, 2021]

“The Mao fad lays bare the paradoxical reality facing the party, which celebrated the centenary of its founding last week. Under President Xi Jinping, the party has made itself central to nearly every aspect of Chinese life. It claims credit for the economic progress the country has made and tells the Chinese people to be grateful. At the same time, economic growth is weakening and opportunities for young people are dwindling. The party has nobody else to blame for a growing wealth gap, unaffordable housing and a lack of labor protections. It must find a way to placate or tame this new generation of Maoists that it helped create, or it could face challenges in governing. “The new generation is lost in this divided society, so they will look for keys to the problems, ” a Maoist blogger wrote on the WeChat social media platform. “In the end, they’ll definitely find Chairman Mao.”

“In interviews and online posts, many young people said they could relate to Mao’s analysis of Chinese society as a constant class struggle between the oppressed and their oppressors. “Like many young people, I’m optimistic about the country’s future but pessimistic about my own, ” said Du Yu, a 23-year-old who is suffering from burnout from his last job as an editor at a blockchain start-up in the tech-obsessed Chinese city of Shenzhen. Mao’s writing, he said, “offers spiritual relief to small town youth like me.”

“While Mao never went away, he was once out of fashion. In the 1980s, as freedom and free markets became buzz words, young people turned to books by Friedrich Nietzsche, Jean-Paul Sartre and Milton Friedman. Studying Mao was required in school, but many students blew off those lessons. After the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown, martial arts novels and books by successful entrepreneurs dominated best-seller lists.

“But China has become fertile ground for a Mao renaissance.” Inequality is rife. The party’s growing presence in everyday life has also opened doors for Maoism. Intensifying indoctrination under Mr. Xi has turned the youth both more nationalistic and more immersed in Communist ideology. “New catchphrases among the young reveal this Mao-friendly mind-set. With wages stagnant, young people talk about a “consumption downgrade.” Their employers work them so hard that they call themselves “wage slaves, ” “corporate cattle” and “overtime dogs.” A growing number are saying they would rather become slackers, using the Chinese phrase “tang ping, ” or “lie flat.”

“Those attitudes have helped make the five volumes of “The Selected Works of Mao Zedong” popular again. Photos of fashionably dressed young people reading the books on subways, at the airports and in cafes are circulating online. Students at the Tsinghua University library in Beijing borrowed the book more than any others in both 2019 and 2020, according to the library’s official WeChat account. “I’ll definitely reread the ‘Selected Works’ again and again in the future, ” a young blogger named Mukangcheng wrote on Douban, a Chinese social media service focused on books, film and other media. “It has the power to make a person searching in darkness see the light. It makes my weak soul strong and broadens my narrow worldview.”

“Mukangcheng, who declined to give me his real name, uses an email account named “Left Left.” His portrait is a red Mao badge. His posts concern high pork prices and lack of money for his phone bills. In 2018, when he visited the site of the Communist Party’s first national congress in Shanghai, he wrote on the visitors’ book, quoting Mao, “Never forget class struggle!” Others commenting online about “Selected Works” said they saw themselves in the young Mao, an educated village youth from a backwater province trying to make it in the early 1900s in the big city then known as Peking. They usually call Mao “teacher, ” a term he preferred to call himself.

Cultural Revolution’s Sent-Down Youths Revived?

In 2019, the Chinese government announced plans to send millions of students from cities to the countryside to 'develop' rural areas, which reminded many of the the Sent-Down Youth movement of Mao's Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 70s. Around 10 million Communist Youth League students will be sent to 'rural zones' by 2022 to help villagers “increase skills, spread civilisation and promote science” according to a Communist Party document.. [Source: AFP, April 12, 2019]

AFP reported: “The aim is to bring to the rural areas the talents of those who would otherwise be attracted to life in the big cities, according to a CYL document quoted in the official Global Times. “'We need young people to use science and technology to help the countryside innovate its traditional development models, ' Zhang Linbin, deputy head of a township in central Hunan Province, told the state-run Global Times.

“Students will be called upon to live in the countryside during their summer holidays, although the CYL did not say how young people would be persuaded to volunteer. Former revolutionary bases, zones suffering from extreme poverty and ethnic minority areas will receive top priority, according to the CYL. Relations are often fraught between the Han majority, who make up more than 90 percent of the population, and ethnic minorities like the Tibetans and Muslim Uighurs.

“Users on the Twitter-like Weibo social platform reacted warily. Many evoked the chaos of the 1966-76 Cultural Revolution, when Mao sent millions of 'young intellectuals' into often primitive conditions in the countryside, while universities were closed for a decade. 'Has it started again?' wondered one user named WangTingYu. 'We did that 40 years ago, ' wrote Miruirong. 'Sometimes history advances, sometimes it retreats, ' noted KalsangWangduTB. President Xi Jinping, known for his nostalgia for the Mao era, himself spent seven years in a village in the poor northern province of Shaanxi from the age of 16

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021