WOMEN UNDER COMMUNISM IN CHINA

In the early 20th century the situation for women began improving in China as Western ideas began take hold. Foot binding was banned and there were efforts to improve the literacy of women. Under Communism, things improved further. Child marriages, prostitution, arranged marriages and concubines were banned. When the Communist Party came to power in 1949, it gave women greater rights, including the freedom to work and marry who they liked.

The Communists are proud of their women's right record. Mao used to say, "Women hold up half the sky" — an ancient Chinese proverb. The Communists raised the status of women and made them useful members of the revolution. They did a lot to improve the health care and education of women, and helped them enter the work force as pilots, doctors, factory workers and farm machine operators and currently are trying to combat the cultural preference for boys.

The Communist system empowered women to work outside the home which in the end, in many cases, just doubled their work load — because they were still expected to take care of the house and raise the children when they weren't working. A typical woman in the Maoist era rose at 5:00am in cramped apartment with her family and parents to fix breakfast for everyone and get her kids off to school. She then took a crowded bus to work. At 2:00pm she got off work and then rushed to the butcher shop with a ration card and queued for meat and after she was done rushed to another store to wait in another line for vegetables. After arriving at her apartment bloc she walked up the stairs because the elevator didn’t work, fixed dinner, washed the dishes and collapsed into bed exhausted only to have to wake again the next day and do it all over again.*

Under the Deng reforms, things improved. Women were able to chose their jobs and careers, improve their status and gain more freedom over their lives. Improved status meant that women no longer had to obediently follow the orders of their in laws. They could pick their boyfriends and husbands, chose where they wanted to live, and enjoy life in a way they would have never dreamed of in the past.

Progress was always limited though. Women remain few in number in the top ranks of the Communist Party and China's biggest companies. “The Party “aggressively perpetuates gender norms and reduces women to their roles as dutiful wives, mothers, and baby breeders in the home, in order to minimize social unrest and give birth to future generations of skilled workers,” wrote Leta Hong Fincher, the author of “Betraying Big Brother: the Feminist Awakening in China” (2018). On some levels gender equality has reversed in recent decades. According to Quartz: “Women are frequently the target of sexist jokes — including on national television. In one notorious example, a Chinese New Year gala in 2015, hosted by state broadcaster CCTV and viewed by over 690 million people, depicted unmarried women over 30 as second-hand goods in a sketch. In another, it hinted that female officials slept their way to the top. “Meanwhile, the space for activism or even discussion of gender-related topics in China has shrunk in recent years, part of a larger crackdown on freedom of speech under president Xi Jinping. In 2015, Beijing arrested five young feminists for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble,” a charge often used to target activists. The move forced many feminists to self-censor or go underground. [Source: Jane Li, Quartz, January 23, 2021

See Separate Articles:CHINESE WOMEN factsanddetails.com ; WOMEN IN TRADITIONAL CHINESE SOCIETY factsanddetails.com ; HARD LIFE OF WOMEN IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CONFUCIAN VIEWS AND TRADITIONS REGARDING WOMEN factsanddetails.com CONCUBINES AND MISTRESSES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com WORKING WOMEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com PROBLEMS FACED BY WORKING WOMEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com SUCCESSFUL WORKING WOMEN IN CHINA: DONG MINGZHU AND SHENGNU LADIES factsanddetails.com MEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; DISCRIMINATION AGAINST WOMEN AND WOMEN'S RIGHTS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; DOMESTIC VIOLENCE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; WOMEN TRAFFICKING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; FOOT BINDING AND SELF-COMBED WOMEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHILDREN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHILD REARING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; FAMILIES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TRADITIONAL CHINESE FAMILY factsanddetails.com ;

Good Websites and Sources: Women in China Sources fordham.edu/halsall ; Chinese Government Site on Women, All-China Women's Federation (ACWF) Women of China ; Human Trafficking Human Trafficking and Modern Slavery in China gvnet.com ; International Labor Organization ilo.org/public Foot Binding San Francisco Museum sfmuseum.org ; Angelfire angelfire.com ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Women in Revolutionary China “Women and China's Revolutions” by Gail Hershatter Amazon.com; “To the Storm: the Odyssey of a Revolutionary Chinese Woman” by Yue Daiyun and Carolyn Wakeman Amazon.com; “A Daughter of Han: The Autobiography of a Chinese Working Woman” by Ida Pruitt (1945) Amazon.com; Women in Pre-Revolutionary China “Instructions for Chinese Women and Girls” by Zhao Ban, Esther E Jerman, Amazon.com ; “The Chinese Book of Etiquette and Conduct for Women and Girls, Entitled, Instruction for Chinese Women and Girls” (1900) by Chao Pan Amazon.com; “The Mother (1931) by Pearl S. Buck Amazon.com

"What Women Should Know About Communism" by He Zhen

He Zhen

He Zhen was the wife of the anti-Manchu anarchist leader Liu Shipei (1884-1917). The essay below appeared in the journal Natural Justice, which He Zhen and Liu Shipei published while in exile in Japan.

In “What Women Should Know About Communism” He Zhen wrote: “What is the most important thing in the world? Eating is the most important. You who are women: what is it that makes one suffer mistreatment? It is relying on others in order to eat. Let us look at the most pitiable of women. There are three sorts. There are those who end up as servants. If their master wants to hit them, he hits them. If he wants to curse them, he curses them. They do not dare to offer the slightest resistance, but slave for him from morning to night. They get up at four o’clock and do not go to bed until midnight. What is the reason for this? It is simply that the master has money and you depend on him in order to eat.

“There are also women workers. Everywhere in Shanghai there are silk factories, cotton mills, weaving factories, and laundries. I don’t know how many women have been hired by these places. They too work all day into the evening, and they too lack even a moment for themselves. They work blindly, unable to stand straight. What is the reason for this? It is simply that the factory owner has money and you depend on him in order to eat.

“Thus those of us who are women suffer untold bitterness and untold wrongs in order to get hold of this rice bowl. My fellow women: do not hate men! Hate that you do not have food to eat. Why don’t you have any food? It is because you don’t have any money to buy food. Why don’t you have any money? It is because the rich have stolen our property. They have forced the majority of people into poverty and starvation. Look at the wives and daughters in the government offices and mansions. They live extravagantly with no worries about having enough to eat. Why are you worried every day about starving to death? The poor are people just as the rich are. Think about it for yourselves; this ought to produce some disquieting feelings.

See He Zhen (wife of Liu Shipei, 1884-1917) "What Women Should Know About Communism" [PDF] afe.easia.columbia.edu

Participation of Chinese Women in the Communist Revolution

Chinese women did their part fighting for the Communists against the Kuomintang. One unit was immortalized in the movie and ballet “Red Detachment of Women”, whose theme song featured the memorable lyrics: "March on, march on. A soldier's burden is heavy. A woman’s hatred is deep." The detachment emerged in 1930s from a group of women who helped the war effort by mending uniforms. They claimed the could carry weapons like men, the story goes, and ended up participating in hundreds of bloody battles, sometimes fighting with their bare hands.

Helen Gao wrote in the New York Times: My grandmother likes to tell stories from her career as a journalist in the early decades of the People’s Republic of China. She recalls scrawling down Chairman Mao’s latest pronouncements as they came through loudspeakers and talking with joyous peasants from the newly collectivized countryside. In what was her career highlight, she turned an anonymous candy salesman into a national labor hero with glowing praises for his service to the people. [Source: Helen Gao, New York Times, September 25, 2017; Helen Gao is a social policy analyst at a research company and a contributing opinion writer.]

“She had grown up in the central province of Hunan, where her father was a landlord. She talks about her mother as a glum housewife who resented her husband for taking a concubine after she had failed to give birth to a boy. “The Communists did many terrible things,” my grandmother always says at the end of her reminiscences. “But they made women’s lives much better.” That often-repeated dictum sums up the popular perception of Mao Zedong’s legacy regarding women in China. As every Chinese schoolchild learns in history class, the Communists rescued peasant daughters from urban brothels and ushered cloistered wives into factories, liberating them from the oppression of Confucian patriarchy and imperialist threat.

Women Under Early Communist Rule in China

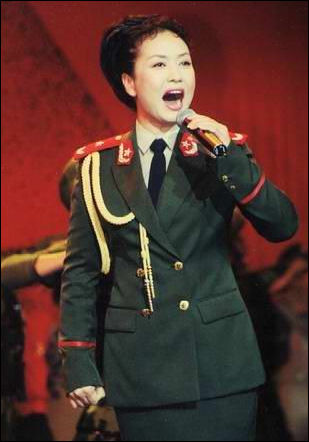

Peng Liyuan, wife of

Xi Jinping, the next leader of China Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “The labor force also increased as a result of the "liberation" of women, in which the marriage law of April 1950 was the first step. Nationalist China had earlier created a modern and liberal marriage law; moreover, women were never the slaves that they have sometimes been painted. In many parts of China, long before the Pacific War, women worked in the fields with their husbands. Elsewhere they worked in secondary agricultural industries (weaving, preparation of food conserves, home industries, and even textile factories) and provided supplementary income for their families. All that "liberation" in 1950 really meant was that women had to work a full day as their husbands did, and had, in addition, to do house work and care for their children much as before. The new marriage law did, indeed, make both partners equal; it also made it easier for men to divorce their wives, political incompatibility becoming a ground for divorce. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1977, University of California, Berkeley]

“The ideological justification for a new marriage law was the desirability of destroying the traditional Chinese family and its economic basis because a close family, and all the more an extended family or a clan, could obviously serve as a center of resistance. Land collectivization and the nationalization of business destroyed the economic basis of families. The "liberation" of women brought them out of the house and made it possible for the government to exploit dissension between husband and wife, thereby increasing its control over the family. Finally, the new education system, which indoctrinated all children from nursery to the end of college, separated children from parents, thus undermining parental control and enabling the state to intimidate parents by encouraging their children to denounce their "deviations." Sporadic efforts to dissolve the family completely by separating women from men in communes — recalling an attempt made almost a century earlier by the Taiping — were unsuccessful.

Propaganda and Women in Communist China

Helen Gao wrote in the New York Times: “The state rolled out propaganda campaigns aimed at not only enlisting women in the work force but also shaping their self-perception. Posters, textbooks and newspapers propagated images and narratives that, devoid of any particularities of personal experiences, depicted women as men’s equal in outlook, value and achievement. For women in the workplace to adhere to this narrowly defined acceptable female image meant to see, understand and speak about their life not as it was, but as what it ought to be according to the party ideal. [Source: Helen Gao, New York Times, September 25, 2017;

“It is a measure of the campaign’s success that women who publicly described their experiences in the Mao era did so exclusively in official rhetoric. Elisabeth Croll, an anthropologist specializing in Chinese women, observed that all published accounts of Chinese women’s lives during the early decades of the People’s Republic followed the standard narrative of their rise from mistreated wives and daughters to independent, socialist workers; it had become the story of practically every woman.

“Forty years after Mao’s death, this aspect of his legacy is still understood through his famous pronouncement on gender equality, “Women hold up half the sky.” It is a slogan my grandmother utters in the same breath as the chairman’s other sins and deeds. She does not mention the arduous work of managing a household and raising three children amid tumultuous revolutionary campaigns. Nor does she complain about how she couldn’t join the party because of her husband’s unpopular political affiliations. She gives only a chuckle when she recalls the exhortations she once received from party superiors to marry just as her career was taking off.

Women Can Hold up Half the Sky

"Women can hold up half the sky" is attributed to Mao Zedong. It appeared in communist propaganda during the Great Leap Forward movement in China in the late 1950s but is based on an ancient — some say Taoist — proverb. Liana Zhou and Joshua Wickerham wrote in the “Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender”: “This slogan symbolized the efforts of the CCP and the state to address the women's movement as part of its political and ideological mission. Early CCP ideology argued that women's liberation could only be accomplished when all working people were liberated. Only when the proletarians took complete control of political power would women reach full liberation. [Source: Liana Zhou and Joshua Wickerham, “Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender: Culture Society History”, Thomson Gale, 2007]

“In 1940 an editorial in People's Daily, the official newspaper of the CCP, stated that modern Chinese women must participate fully in all movements that benefit the state and nation in order to realize their own liberation. In 1949, when the CCP successfully established political control of the entire country, the party mandated that women enter the work force on an equal par with men. A woman's value and liberation were tied to her productivity and contribution to society.

“In film, art, literature, opera, and ballet, during the time of the Cultural Revolution, female characters were often portrayed as political activists or military figures who, without exception, were unmarried revolutionaries, determined and devoted to communist ideals. Eight operas were promoted during the ten years of the movement, all of which had female protagonists aged twenty to sixty, and all of whom were presented as political entities rather than individuals. Overt expressions of feminine appearance and conduct were denounced. Women wore the same clothing as men, with only a slight style difference. The Red Guard, the CCP's youth league, expressed its disapproval of anyone who dressed differently; members monitored people in the streets and cut trousers they deemed to be too long. Scholars have used the term socialist androgyny to describe the reworking of female gender during this period. Many scholars, in China and elsewhere, consider this approach to women's liberation as a denial of the European and North American concept of feminism, which refers to a gendered analysis of the position and representation of women in society.

Laws, Changes and Improvements for Women in Communist China

A real liberation and revolution in the female’s role has occurred in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The first law enacted by the PRC government was the Marriage Law of 1950. The law is not only about marriage and divorce, it also is a legal statement on monogamy, equal rights of both sexes, and on the protection of the lawful interests of women and children. [However, it took years for the law to become more than words on paper and move into real life. (Lau)] [Source: Zhonghua Renmin Gonghe Guo, Fang-fu Ruan, M.D., Ph.D., and M.P. Lau, M.D. Encyclopedia of Sexuality =]

In 1954, the constitution of the People’s Republic of China restated the 1950 principle of the equality of men and women and protection of women: “Article 96. Women in the People’s Republic of China enjoy equal rights with men in all spheres of political, economic, cultural, social, and domestic life.” Under this principle, major changes happened in the social roles of women in the PRC, especially in the areas of work and employment, education, freedom in marriage and divorce, and family management. For example, 600,000 female workers and urban employees in China in 1949 accounted for 7.5 percent of the total workforce; in 1988 the female workforce had increased to 50,360,000 and 37.0 percent of the total. [Most women continue to be employed as cheap labor, but this is not a condition limited to China. (Lau)] =

A neighborhood survey in Nanjing found that 70.6 percent of the women married between 1950 and 1965 had jobs. Of the women married between 1966 and 1976, those employed stood at 91.7 percent, and by 1982, 99.2 percent of married women were breadwinners. A Shanghai neighborhood survey reported 25 percent of the wives declared themselves boss of the family, while 45 percent said they shared the decision making power in their families. Similar surveys in Beijing found that 11.6 percent of the husbands have the final say in household matters, while 15.8 percent of families have wives who dominate family decision making. The other 72.6 percent have the husband and wife sharing in decision making. A survey in Nanjing revealed that 40 percent of the husbands go shopping in the morning. Many husbands share kitchen work. Similar surveys of 323 families in Shanghai found 71.1 percent of husbands and wives sharing housework. (Dalin Liu’s study of Sexual Behavior in Modern China (1992) contains statistical data about domestic conflicts and the assignment of household chores.)

Although the situation of women changed dramatically from what was before, in actuality, women still were not equal with men. For example, it is not unusual to find that some universities reject female graduate students, and some factories and government institutions refuse to hire women. The proportion of professional women is low. Of the higher-level jobs such as technicians, clerks, and officials, women fill only 5.5 percent. Of the country’s 220 million illiterates, 70 percent are women. Women now make up only 37.4 percent of high school students and only 25.7 percent of the university-educated population. Moreover, actual discrimination against women still exists, and continues to develop now. Many women have been laid off by enterprises that consider them surplus or redundant. Only 4.5 percent of the laid-off women continued to receive welfare benefits, including bonuses and stipends offered by their employers. Many enterprises have refused to employ women, contending their absence from work to have a baby or look after children are burdensome.

Impacts of Communism on Chinese Women

Helen Gao wrote in the New York Times:“While the Communist revolution brought women more job opportunities, it also made their interests subordinate to collective goals. Stopping at the household doorstep, Mao’s words and policies did little to alleviate women’s domestic burdens like housework and child care. And by inundating society with rhetoric blithely celebrating its achievements, the revolution deprived women of the private language with which they might understand and articulate their personal experiences. [Source: Helen Gao, New York Times, September 25, 2017

“When historians researched the collectivization of the Chinese countryside in the 1950s, an event believed to have empowered rural women by offering them employment, they discovered a complicated picture. While women indeed contributed enormously to collective farming, they rarely rose to positions of responsibility; they remained outsiders in communes organized around their husbands’ family and village relationships. Studies also showed that women routinely performed physically demanding jobs but earned less than men, since the lighter, most valued tasks involving large animals or machinery were usually reserved for men.

“The urban workplace was hardly more inspiring. Women were shunted to collective neighborhood workshops with meager pay and dismal working conditions, while men were more commonly employed in comfortable big-industry and state-enterprise jobs. Party cadres’ explanations for this reflected deeply entrenched gender prejudices: Women have a weaker constitution and gentler temper, rendering them unfit for the strenuous tasks of operating heavy equipment or manning factory floors.

“The party at times paid lip service to the equal sharing of domestic labor, but in practice it condoned women’s continuing subordination in the home. In posters and speeches, female socialist icons were portrayed as “iron women” who labored heroically in front of steel furnaces while maintaining a harmonious family. But it was a cherry-picking approach that focused exclusively on bringing women into the work force and neglected their experiences in other realms.

“Visitors to rural areas saw peasant wives toiling around the clock: cooking, mending clothes and feeding livestock after finishing a day of work in the fields. Their plight shocked the urban youth who were sent down to the countryside during the Cultural Revolution, such that Naihua Zhang, a sociology professor at Florida Atlantic University who spent time in the countryside as a young woman in that era, equated rural marriage with a total erasure of women’s identity.

“Researchers also observed that after marriage factory women often experienced slower career advancement than men as they became saddled with domestic responsibilities that left them with little time to learn new skills and take on extra work, both prerequisites for promotion. State services that promised to ease their burden, like public child care centers, were in reality few and far between. Unlike their counterparts in developed countries, Chinese women didn’t have labor-saving household appliances, since Mao’s economic policies prioritized heavy industry over the production of consumer products like washing machines and dishwashers.

“Some Western scholars have said these realities amounted to a “revolution postponed.” Yet the conclusions of researchers were contradicted by none other than Chinese women themselves. During her field study in China in 1970s, Margery Wolf, who was an anthropology professor at University of Iowa, was surprised by how effusive Chinese women were about the miracle of female emancipation in the very presence of their continued oppression. “It was easy to take gender equality — an ideal that was widely promoted — as the reality and regard problems as reminiscent of old systems and ideology that would erode with time,” said Professor Zhang, the sociologist.

“For all its flaws, the Communist revolution taught Chinese women to dream big. When it came to advice for my mother, my grandmother applauded her daughter’s decision to go to graduate school and urged her to find a husband who would be supportive of her career. She still seems to think that the new market economy — with its meritocracy and freedom of choice — will finally allow women to be masters of their minds and actions. “After all, she has always said to my mother, “you have more opportunities.”

Growing up with an Absent Mother in the Mao Era

In “Message from an Unknown Chinese Mother: Stories of Loss and Love”, Xinran wrote: As a child, I used to believe I was an orphan, because my mother gave me a life but had no time to love me, nor believed she should make any special effort to be with me. From the 1950s to the 1970s, most Chinese women like my mother closely followed the Communist Party's line concerning your "life order"” in other words, the political party came first, your motherland came second and helping others came third. Anyone who cared about their own family and children was considered a capitalist and could be punished — at the very least, you would be looked down upon by everyone, including your own family. So, exactly a month after I was born, I was sent away to live with my grandmothers, spending my time between Nanjing and Beijing. [Source: Message from an Unknown Chinese Mother: Stories of Loss and Love” by Xinran, The Guardian, April 24, 2011]

I wasn't the only one; for millions of Chinese children growing up in that Red period, life was lived without our mothers. Their busy careers as "liberated women" — part of the victimization of the Cultural Revolution — kept them away from us. And then, when I grew up, I moved away to university and we were living in different cities, different time zones — and, finally, different countries.

But I know how much I miss her, when I'm chatting to my family, writing — even when I'm on book tours around the world and in the night, I often dream of when I was a little girl. With one hand I hold the baby doll, which was taken from me by a female Red Guard on the first day the Cultural Revolution took place at my town; with the other hand I hold two of my mum's fingers. In the dream, she always wears the purple silk dress she had on in my first real-life memory of her, when I was five.

My grandmother took me to a railway station to meet her there — she was on a business trip. "This is your mother: say 'Mama', not 'Auntie'," my grandmother told me, embarrassed. Wide-eyed and silent, I stared at the woman in the purple dress. Her eyes filled with tears, but she forced her face into a sad, tired smile. My grandmother did not prompt me again; the two women stood frozen...This particular memory has haunted me again and again. I felt the pain of it most keenly after I became a mother myself and experienced the atavistic, inescapable bond between a mother and her child. What could my mother have said, faced with a daughter who was calling her "Auntie"

Xinran and Messages from an Unknown Chinese Mother

Wu Yi

Lesley Downer wrote in the New York Times: “Xinran was a radio journalist in Nanjing until moving to Britain in 1997. Before her departure, her program for women, “Words on the Night Breeze,” had millions of listeners: at that time, few Chinese owned televisions and many were illiterate, so radio journalists reached far more people than their colleagues on television or at newspapers. Xinran received hundreds of letters and phone calls, and told some of her correspondents’ harrowing stories on air.

Her program — and her 2010 book “Message from an Unknown Chinese Mother: Stories of Loss and Love” “gave a voice to some of the poorest women in Chinese society, whose stories would otherwise never be heard. Among them are women like Kumei, a dishwasher who twice tried to kill herself because she’d been forced to drown her baby daughters. When a child is born, Kumei explains, the midwife prepares a bowl of warm water — called Killing Trouble water, for drowning the child if it’s a girl, or Watering the Roots bath, for washing him if it’s a boy.

Xinran also investigates Chinese orphanages, for many of which the word “Dickensian” would be totally inadequate. The children abandoned there are almost always girls, and they regularly arrive with burns between their legs, marks made as the midwife holds the newborn under an oil lamp to check her sex. Mothers forced to abandon their babies often leave mementos in their clothing, hoping the children will be able to trace them later on, but the orphanages routinely throw these sad tokens away.

Separated from her mother by the Cultural Revolution, Xinran grew up with her grandparents and considered herself an orphan. Years later, she founded a charity called the Mothers’ Bridge of Love for Western families who adopt Chinese children. Downer wrote “Message From an Unknown Chinese Mother” is full of heart-rending tales. “They are raw and shocking, simply told and augmented with passages that provide information about matters like the one-child policy, the history of orphanages and Chinese adoption laws.”

Book:”Message from an Unknown Chinese Mother: Stories of Loss and Love” by Xinran, translated by Nicky Harman Scribner in the U.S., Chatto and Windus on the U.K., 2010)

Women in Government in China

Women account for around 20 percent of the National People's Congress members and less than a fifth of Communist Party members. As of 2003, there were only five women in the high-ranking 198-member Central Committee and only one woman in the 24-member Politburo.

There are a fairly large number of female party officials but they generally don't have high-level jobs. In 1994, 32.6 percent of the Chinese officials were women but only 10.7 percent of the officials above the county level, just one of the country's 13 state councilors and three of its 40 ministers were female.

In August 2005 China promised to improve women’s representation in politics.

Vice Premier and Health Minister Wu Yi is the highest-ranking women official in China and the only female politburo member. Appointed health minister during the SARS crisis, she is very popular and has a reputation for carrying about people. Some think she is a reincarnation of the Buddhist goddess of Mercy, Kwan-yin

Wu Yi is an Oxford-educated economist and former petroleum engineer. She represented China during trade negotiations between China and the United States in 2006. One U.S. official described her as “an impressive interlocutor — very direct and very capable of getting things done.”

In 2007, Wu Yi was ranked as the second most powerful woman in the world for the second year in a row by Forbes magazine, placing behind German Chancellor Angela Merkel and ahead of U.S. Secretary of State Condolezza Rice.

Women Dance and Sing into the Chinese Military

In some places women applying to be army officers have show off their “talents” as well as make a favorable impression in a face-to-face interview. Meng Jing wrote in the China Daily: “Aspiring female officers were surprised to learn...that they are now required to perform a 'talent' as part of the country's current recruitment drive for the People's Liberation Army (PLA). The test of artistic ability was included for the first time as part of the standard face-to-face interview by recruiters on behalf of the PLA, which took place following stringent health screenings. [Source: Meng Jing, China Daily November 30, 2009]

“I was shocked by the new talent show test when I first heard about it,” said Zhang Jing, a candidate from Beijing Union University who opted to read a piece of poetry told the China Daily. A law major from the Beijing Normal University called Zhang Wenbian said: “Ithought the talent show was a little unnecessary.”

“Lieutenant Colonel Ding Zhengquan from the Beijing recruitment office said they only want to choose the best eligible young women, Meng Jung wrote. “Ding confirmed there are limited vacancies for female applicants compared with their male counterparts, which is why standards have been raised.... Wang Bosheng, a judge in the Haidian district section and a member of the National People's Congress, believed the artistic element was essential. “It is amazing to see so many girls with such great gifts,” Wang said. He added it would help them select the right people for the army.”

The army interview for women includes a 30-second self-introduction, a 150-second question and answer period, and a 2-minute talent show....Han Sheng, a student from Minzu University of China, displayed two of her paintings to the judges. Han admitted she was surprised by the talent show: It's only 2 minutes; some talents cannot be presented in such a short time.”... The face-to-face interview has a total mark of 30. The talent show counts for 8 marks with “expression” and “impression” providing another 12 and 10. In order to ensure interview fairness, mobile signals were blocked in all examination rooms and questions were picked randomly by applicants.

Wang Qian, a vice battalion commander in the Second Artillery Force, reviewed the female applicants in Haidian district on Saturday in the hope of finding suitable women for her battalion. Wang believed it was extremely necessary to include the talent shows, and told the China Daily, “Female soldiers are a special element of the army.” She said the army did not only want someone who is intelligent. “We want to find those candidates who are great in every field,” she said.

Image Sources: 1) Historical photos, Lotte Moon and University of Washington; 2) Posters, Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/; 3) Village woman, Beifan Urban woman, cgstock.com http://www.cgstock.com/china ; Wiki Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2021