CHINESE PERSONALITY AND CHARACTER

Citizens poster from the 1920sChinese have described themselves as harsh, tenacious, unpredictable, materialistic, greedy, secretive, direct, suspicious, stoic, warm, xenophobic, respectful and insensitive. They can be very hard working but also have a reputation for corruption and arbitrariness. Among the traits that Chinese consumers said they admired most in a marketing study were diligence, self-confidence, respect, talent, heroism and light-heartedness.

Traditional Chinese values include love and respect for the family, integrity, loyalty, honesty, humility, industriousness, respect for elders, patience, persistence, hard work, friendship, commitment to education, belief in order and stability, emphasis on obligations to the community rather just individual rights and preference for consultation rather then open confrontation. These values are generally shared by other Asians and are drilled into children from nursery school onward.

Geoffrey Blowers, a professor of psychology at Hong Kong University, told the Times of London, “In Judaeo-Christian culture, with its belief in a personal connection with God, there is a tradition of improvement through self-examination. In the Chinese cosmological system the emphasis is on continuity, and the need to fit in with one’s surroundings.” He adds that in Western “guilt culture” people are more used to bearing their souls while in Asian ‘shame culture” people are taught to be more discreet lest they bring shame to their families.

Websites and Sources: Book: Understanding the Chinese Personality mellenpress.com ; Understanding Chinese Business Culture legacee.com ; Status of Chinese People Blog chinaview.wordpress.com ; Chinese Human Genome Diversity Project www.pnas.org ; Opinions on Asian Fetish colorq.org ; ; Essay on Humor, China and Japan aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; . Book: One of the most enlightening books about China is “Chinese Lives” by Sang Ye and Zhang Xinxin, a series of interviews with ordinary Chinese talking very candidly about what matter to them.

See Separate Articles ASIAN CHARACTER AND PERSONALITY factsanddetails.com ; PEOPLE OF CHINA: DIVERSITY, ASSIMILATION, HAN AND ETHNIC RELATIONS factsanddetails.com ; HAN CHINESE factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS AND STRENGTH factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PERSONALITY TRAITS: INDIRECTNESS, PRAGMATISM, COMPETITION AND FACE factsanddetails.com ; SOCIALIZING AND SOCIAL CUSTOMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HAPPINESS AND PSYCHOLOGICAL PROBLEMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HUMOR IN CHINA: ITS HISTORY AND FORMS OF EXPRESSION factsanddetails.com ; STRESS, ARGUING AND BULLIES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CALLOUSNESS IN CHINA, GOOD SAMARITANS AND THE HIT-AND-RUN DEATH OF A TWO-YEAR-OLD factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE CHARACTERISTICS”: A SEMI-RACIST BUT INSIGHTFUL VIEW OF CHINA FROM 1894 factsanddetails.com ; REGIONAL DIFFERENCES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; BEIJING VERSUS SHANGHAI factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE SOCIETY, CONFUCIANISM, CROWDS AND VILLAGES Factsanddetails.com/China ; CHINESE SOCIETY AND COMMUNISM Factsanddetails.com/China ; RELIGION, FOLK BELIEFS AND DEATH ( Main Page, Click Religion) Factsanddetails.com/China JAPANESE PERSONALITY AND CHARACTER Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE SOCIETY Factsanddetails.com/Japan

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Chinese Mind: Understanding Traditional Chinese Beliefs and Their Influence on Contemporary Culture” (2009) by Boye Lafayette De Mente Amazon.com; “Culture Hacks: Deciphering Differences in American, Chinese, and Japanese Thinking” by Richard Conrad Amazon.com; Amazon.com; “It's All Chinese To Me: An Overview of Culture & Etiquette in China” by Pierre Ostrowski Matthew B. Christensen, Gwen Penner (Illustrator) Amazon.com; “China in Ten Words” by Yu Hua, translated from the Chinese by Allan H. Barr (Pantheon) Amazon.com; “Chinese Characters: Profiles of Fast-Changing Lives in a Fast-Changing Land” by Angilee Shah, Jeffrey Wasserstrom, et al. (2012) Amazon.com; Good Luck Life: The Essential Guide to Chinese American Celebrations and Culture”by Rosemary Gong and Martin Yan Amazon.com; “China Men”, a National Book Award Winner by Maxine Hong Kingston Amazon.com; “Understanding the Chinese Personality: Parenting, Schooling, Values, Morality, Relations, and Personality” (1998) by William J. F. Lew Amazon.com; “Niubi!: The Real Chinese You Were Never Taught in School” by Eveline Chao and Chris Murphy Amazon.com; “The Ultimate Chinese Dictionary of Swear Words: a Chinese Phrase Book of Essential Colloquial Chinese Slang With Contextual Information and Sample Sentences by Liu San Amazon.com; “The Guide to Chinese Horoscopes: The Twelve Animal Signs” by Gerry Maguire Amazon.com; “Chinese Characteristics” (1894) by Arthur H Smith Amazon.com; “Readings in Han Chinese Thought” by Mark Csikszentmihaly Amazon.com; “The Good Earth” by Pearl Buck(1931). Amazon.com;“The Book of Chinese Names: A Guide to Auspicious and Elegant Names” by Goh Kheng Chuan and Goh Kheng Yew Amazon.com

Different Impressions of the Chinese Personality and Character

According to to a guide prepared by VisitBritain Chinese do not tolerate discussions about money and Hong Kongers get the creeps at historic houses as they are superstitious and fear “ghostly encounters.” Cong Zhong, a professor and psychoanalyst at Beijing Medical College, told the Times of London, “Deep down, Chinese people have the same repressed feelings, desires and problems" as Westerners. The five traditional blessings are prosperity, happiness, passion, health and good luck. Patience and diligence and family are also highly valued. [Source: The Times, January, 2014]

Some Non-Chinese find the Chinese crude and pushy yet humble and shy. The writer Paul Theroux wrote the Chinese he encountered "were very tidy in the way they dress and packed their things, but they were energetic litterers and they were hellish in toilets...They spat, they shouted, they stared and undressed in public; and yet with all this they seldom quarreled. They were extremely shy — timid even — modest and naive."

Research by the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) has made the following points: 1) Elder Chinese people have better sense of responsibility than youngsters. 2) Younger male Chinese are more practical or realistic (actual) than younger female Chinese. 3) Youngsters are more tactful or sophisticated than elder people. 4) Hong Kong people are more practical or realistic than mainland Chinese. 5) Mainland Chinese value face more than Hong Kong Chinese people. 6) As for "Family Indifference", 26 - 35 aged Chinese score best. 7) Hong Kong elders show more tendency to be self-centered. 8) Tolerance of mainland Chinese elders increase, Hong Kong elders decrease. 9) Guangzhou people are more pro-active, energetic, positive than Xian people. 10) better living standards has produced the more open-minded and tolerant Chinese. 12) U.S. people are generally more open, straight-forward and optimistic that Chinese. 13) According to US standard, many Chinese have a sort of "a tendency to suffer from depression". 14) Chinese interpersonal relationship usually follows some "hidden rules" — Chinese people look for harmonious, relationships but often they have their own ambitions and interests.

Da Ji Yuan wrote in the Epoch Times: 1) Chinese prefer cautious, experienced and prudent behavior, sentiments being expressed in a reserved way and well-disciplined types of people. 2) Chinese spend much effort at interpersonal relationship — trying to understand or/and guess others. 3) Tolerance and patience are Chinese' skills for living and survival in hard and unfair environment. 4) Foreigners think Chinese are phony. It's true Chinese are inconsistent with what they say and what they think, often protecting themselves from making troubles. 5) China emphasizes "fewer mistakes" education, hence, students better follow orders, and are more disciplined. 6) Chinese usually don't criticize existed system, resulting in a kind of inertia or conservative view. [Source: Da Ji Yuan, Epoch Times, June 4, 2001]

Problems of Defining Chinese Character

There does seems to be some character differences between Asians and Westerners but defining these differences and interpreting their significance is difficult and even dangerous. It has been said for example that Asian societies place more emphasis on intuitive insight and tradition than Western societies which are based more on logic. But defining exactly what tradition, intuitive insight and logic are is difficult, especially if you factor in cultural relativity,

It is hard to pin down what is Chinese, National Public radio correspondent Rob Giffrid wrote, “For every fact that is true...the opposite is almost always true as well, somewhere in the country.” The view that Westerners have of China and Chinese is often based on stereotypes and journalistic myths. Only recently has the West begun to understand how complex and diverse China and the Chinese are.

Advertisers have difficulty developing national marketing schemes in China because income levels, education levels and other demographics vary so much from place to place. One advertising researcher, for example, found though focus group studies that young people in Guangzhou are much more “pragmatic cool,” wanting their cell phones to have MP3 players, than their counterparts in Shanghai who wanted an Ipod and a separate, trendy, cell phone. [Source: International Herald Tribune]

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics” in 1894: “No single individual, whatever the extent of his knowledge, could by any possibility know the whole truth about the Chinese. China is a vast whole, and one who has never even visited more than half its provinces, and who has lived in but two of them is certainly not entitled to generalise for the whole Empire. There can be no valid excuse for withholding credit from the Chinese for any one of the many good qualities which they possess and exhibit. At the same time, there is a danger of yielding to ci priori considerations, and giving the Chinese credit for a higher practical morality than they can justly claim. [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894. Smith (1845 -1932) was an American missionary who spent 54 years in China. In the 1920s, “Chinese Characteristics” was still the most widely read book on China among foreign residents there. He spent much of his time in Pangzhuang, a village in Shandong.]

George Wingrove Cooke, the China correspondent of the London Times in 1857-58, wrote: “I have often talked...with the most eminent and candid sinologues, and have always found them ready to agree with me as to the impossibility of a conception of Chinese character as a whole.” A Chinese person “is seen to be irrepressible; is felt to be incomprehensible. He cannot, indeed, be rightly understood in any country but China, yet the impression still prevails that he is a bundle of contradictions who cannot be understood at all. But after all there is no apparent reason now that several hundred years of our acquaintance with China have elapsed, why what is actually known of its people should not be co-ordinated, as well as any other combination of complex phenomena.

Religion, Confucianism and Character

Filial piety

Confucianism puts a strong emphasis and following teachers, superiors, family members and elders. Liu Heung-shin, the editor of a Hong Kong magazine, wrote Chinese identity is "connected to Confucianism, built around families and connections. It's something Chinese people can feel, even if the don't describe it in words."

Love and respect are principals that were practiced more in the context of the family than in society and humanity as a whole and equality was not necessarily the goal of a just society. These ideas help explain why nepotism is so rampant, why Chinese are so horrified by the way Westerners treat the elderly and why the Chinese are more likely to mind their own business if they witness a great injustice being inflicted on a stranger.

Confucian values were displaced somewhat by Communism and Maoism. Since Mao's death and the launching of the Deng economic reforms, Confucianism has made a comeback only to be displaced somewhat by materialism, money and superficial success.

Confucian and Taoism basically contradict and are in conflict with one another. Confucianism, emphasizes achievement and propriety while Taoism stresses unseen strengths in being humble and in some cases, being perceived as average.

Asians often do not seem as self absorbed as Americans. One explanation may be religion. Buddhists talk about diminishing the self and looking to other for guidance and information

See Separate Article ASIAN CHARACTER AND PERSONALITY: HAPPINESS, LOSING FACE, CONFUCIANISM AND BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com

Communism and Character in China

Communism puts a strong emphasis on following authority without questioning it and, initially in China anyway, created a society in which people were equal by poor.

Years of totalitarianism have resulted in a fear of saying what one truly believes. One dissident writer told the New York Times, "The frightening thing about China is that almost every one says one thing in private and the opposite in public, because of the psychological damage, it corrupts society. If offends human dignity." One villager told the reporter Richard Critchfield, "What I hate most is lying. And the Communists were always lying."

“Value-imprinting” — a sort of moral brainwashing — is something that has existed since the time of Confucius and remains very much alive under the Communist Party. Going hand and hand with this, today anyway, is the practice of paying lip service to these values and being guided by a secretive, often more greedy, agenda.

Communism took Confucian paternalism to another level. A character in a Ha Jun novel says,”I spit at China, because it treats its citizens like gullible children and always prevents them form growing up into real individuals. It demands nothing but obedience.” See Human Rights

Years of living under Communism have made older people conservative. Young people are more open and willing to express their ideas.

See Society

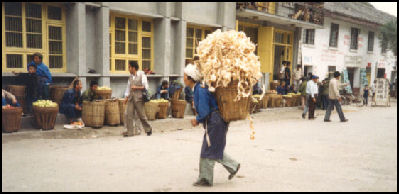

Village Life and Character in China

Villagers all over the world — whether they live in Africa, Poland, Guatemala, or China — often live remarkably similar lifestyles. Often the main thing that separates them is their religious beliefs and aspects of their life determined by the climate and landscape they live in.

Speculating on the illiterate village mind, journalist Alan Berlow wrote: "stories, intrigue, lies, gossip, speculation, gathered like rice in a basket, are tossed up in the air, sending husks to the wind, leaving behind kernels of truth. Truth and half truths, anyway." It is a "missing link, a smoking gun, the connective tissue of random events, the effort to explain things that resist explanation.

Villagers help one another in various ways. They help each other harvest their crops and build their homes. If someone has a serious health problem often everyone pitches in at least some money to help pay the medical bills. They also lend a hand taking care of widows and orphans, fighting fires and helping fix farm equipment.

Village life is often strictly codified. Since everyone knows and gossips about each other, morals tend to be similar. People who stand out or assert themselves as individuals are often regarded with suspicion and hostility by other villagers. People that are different are made fun.

Villagers are often very resourceful and very patient and make the most of available opportunities because they have little choice but to be resourceful and patient and seize the opportunities they may have. When bad things happen they often accept them as manifestations of God's will or the doings of some evil or naughty spirit.

Foreigners, Xenophobia and Nationalism in China

Chinese actor playing a Westerner

The Chinese are often described as xenophobic and nationalistic. While they can be very sensitive and defensive about matters concerning China and Chinese customs, they are often not shy about insulting non-Chinese. One Chinese proverb states: "We can fool any foreigner."

“Scott Savitt, journalist in China since the 1980s, told the Los Angeles Review of Books: “Chinese are used to foreigners being ignorant about China. When they meet people that take the time to learn their language and culture, they want to tell you everything. They want to make you an educated person according to their standards, so they can have deeper interactions with you. I feel like that’s what was done to me. I had to meet that standard. And when I was a reporter there, I was never off duty. Everybody was a source.” [Source: Matthew Robertson LA Review of Books Blog, May 31, 2017]

Frank Hawke, a resident of Beijing since the 1970s, told the New York Times, “A psychological theme that runs throughout China” is that the “Chinese feel they have this great culture, second to none, and yet here they are, a third world developing country. Since 1949, their major goal has been to catch up and surpass the rest of the world in all aspects: culture, national defense, technology, sports. When they feel they’ve made a huge leap forward, there’s an incredible national pride.” A person of Chinese descents who has lived outside China his entire life, but speaks no Chinese, is not labeled a foreigner. After Hong Kong becomes part of China, Chinese citizenship was only offered to people of "Chinese descent." People of Indian descent and mixed racial heritage were denied a Chinese passport because they were not "pure blood" Chinese.

Hurts the Feelings of the Chinese People

Victor Mair wrote in the Language Log, "Spokespersons for the government of the Peoples Republic of China (PRC) often complain that the words or actions of individuals or groups from other nations "hurt the feelings of the Chinese people". This is true even when those individuals or groups are speaking or acting on behalf of some segment of the Chinese population (e.g., political prisoners, Tibetans, Uyghurs, Falun Gong adherents, people whose houses have been forcibly demolished, farmers, and so forth). A typical cause for invoking the "hurt(s) the feelings of the Chinese people" circumlocution would be for the head of state of a country to meet with the Dalai Lama or Rebiya Kadeer. A good example is Mexican President Calderon's recent meeting with the Dalai Lama, which the PRC government denounced in extremely harsh terms. The vitriolic rebuke led one commentator to refer to the PRC denunciation of the Mexican President as a kind of "bullying". [Source: Victor Mair, Language Log September 12, 2011]

I should note that the "hurt feelings" meme usually occurs in tandem with other standard kvetching: “grossly interfered with China’s internal affairs, hurt the feelings of the Chinese people, and harmed Chinese-XYZ relations.” Clearly, this is formulaic language. What is more, because it is used with such frequency in China's dealing with other nations, it quickly begins to lose force and meaning, but amounts to mere blather and cannot be taken all that seriously. Still, its sheer ubiquity makes one wonder: why this obsession with damaged sensitivity?

Finding this expression “"hurts the feelings of the Chinese people" ‘so omnipresent in statements emanating from the PRC government, I wondered how it compares with the usage of analogous statements by representatives of other nations.

Here are ghits (Google hits) for some comparable phrases involving other nations: 1) “hurts the feelings of the Chinese people” 17,000; 2) “hurts the feelings of the Japanese people” 178; 3) “hurts the feelings of the American people” 5; 4) “hurts the feelings of the German people” 2; 5) “hurts the feelings of the Jewish people” 2; 6) “hurts the feelings of the Indian people” 0; 7) “hurts the feelings of the Russian people” 0; 8) “hurts the feelings of the Italian people” 0; 9) “hurts the feelings of the British people” 0; 10) “hurts the feelings of the Swedish people” 0; 11) “hurts the feelings of the French people” 0; 12) “hurts the feelings of the Spanish people” 0; 13) “hurts the feelings of the Tibetan people” 0; 14) “hurts the feelings of the Uighur people” 0; 15) “hurts the feelings of the Uyghur people” 0; 16) “hurts the feelings of the Mongolian people” 0

I started to look around a bit more, and I discovered a number of very interesting analyses of the wounded Chinese soul, including this excellent essay by Joel Martinsen: "Mapping the hurt feelings of the Chinese people in Danwei, from 2008. Even the PRC's own Global Times weighed in on China's hurt feelings in 2009. What do we make of this hugely disproportionate usage of the "hurt feelings" meme by PRC spokespersons vis-à-vis its (non)usage by the spokespersons of other nations? Do Chinese have far more feelings than other people? Are Chinese more pathetic? More bathetic? More pitiable? Having studied Chinese language, literature, and culture for most of my life, I find it hard to comprehend why the PRC spokespersons should concentrate so much on the perceived wounded feelings of their countrymen. Surely it is self-demeaning for a large nation with such a long and illustrious past to focus so heavily on its injured emotions, yet there must be some reason(s) why they do so ad nauseam.

Materialism and the Pursuit of Money in China

Ch'ng Poh Tiong, wine columnist and publisher of The Wine Review, told Reuters:"Chinese people are very aspirational and materialistic so once they have bought the best local brand then they start looking for something even better and more expensive.” [Source: Farah Master, Reuters, January 3, 2011]

Mark Kitto wrote in Prospect Magazine, “Modern day mainland Chinese society is focused on one object: money and the acquisition thereof. The politically correct term in China is “economic benefit.” The country and its people, on average, are far wealthier than they were 25 years ago. Traditional family culture, thanks to 60 years of self-serving socialism followed by another 30 of the “one child policy,” has become a “me” culture. Except where there is economic benefit to be had, communities do not act together, and when they do it is only to ensure equal financial compensation for the pollution, or the government-sponsored illegal land grab, or the poisoned children. Social status, so important in Chinese culture and more so thanks to those 60 years of communism, is defined by the display of wealth. Cars, apartments, personal jewellery, clothing, pets: all must be new and shiny, and carry a famous foreign brand name. In the small rural village where we live I am not asked about my health or that of my family, I am asked how much money our small business is making, how much our car cost, our dog. [Source: Mark Kitto, Prospect Magazine, August 8, 2012]

The trouble with money of course, and showing off how much you have, is that you upset the people who have very little. Hence the Party’s campaign to promote a “harmonious society,” its vast spending on urban and rural beautification projects, and reliance on the sale of “land rights” more than personal taxes. Once you’ve purchased the necessary baubles, you’ll want to invest the rest somewhere safe, preferably with a decent return — all the more important because one day you will have to pay your own medical bills and pension, besides overseas school and college fees. But there is nowhere to put it except into property or under the mattress. The stock markets are rigged, the banks operate in a way that is non-commercial, and the yuan is still strictly non-convertible. While the privileged, powerful and well-connected transfer their wealth overseas via legally questionable channels, the remainder can only buy yet more apartments or thicker mattresses. The result is the biggest property bubble in history, which when it pops will sound like a thousand firework accidents.

In brief, Chinese property prices have rocketed; owning a home has become unaffordable for the young urban workers; and vast residential developments continue to be built across the country whose units are primarily sold as investments, not homes. If you own a property you are more than likely to own at least three. Many of our friends do. If you don’t own a property, you are stuck.

When the bubble pops, or in the remote chance that it deflates gradually, the wealth the Party gave the people will deflate too. The promise will have been broken. And there’ll still be the medical bills, pensions and school fees. The people will want their money back, or a say in their future, which amounts to a political voice. If they are denied, they will cease to be harmonious. Meanwhile, what of the ethnic minorities and the factory workers, the people on whom it is more convenient for the government to dispense overwhelming force rather than largesse? If an outburst of ethnic or labour discontent coincides with the collapse of the property market, and you throw in a scandal like the melamine tainted milk of 2008, or a fatal train crash that shows up massive, high level corruption, as in Wenzhou in 2011, and suddenly the harmonious society is likely to become a chorus of discontent.

China: A Nation of Giant Infants?

A psychology book that argues China is a “nation of infants” has been pulled from store shelves Zheping Huang wrote in Quartz: “According to Sigmund Freud, a human being’s psychosexual development has five stages: the oral, the anal, the phallic, the latent, and the genital. During the oral stage spanning from birth until the age of one, an infant satisfies its desires simply by putting all sorts of things into its mouth, whether it’s a pencil or its mother’s breast. Most Chinese people have never developed beyond the oral stage of Freud’s theory and have the mental age of a six-month-old, argues psychologist Wu Zhihong. In his recently published book Nation of Giant Infants, Wu takes the psychological viewpoint to explain a wide range of social problems in China, including mama’s boys, tensions between mothers and daughter-in-laws, and suicides of left-behind rural kids. He claims that the “giant infant dream” is deeply rooted in the Chinese tradition of collectivism and filial piety. [Source: Zheping Huang, Quartz, March 13, 2017]

““Most Chinese people are infants in search of their mothers,” Wu writes. The 42-year-old provides mental health counseling in major Chinese cities including Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou, and is the author of a series of best-sellers on psychology. Published in December 2016, “Nation of Giant Infants” has recently been removed from Chinese bookshops, drawing speculation among Chinese internet users that censors banned the book because it is offensive to Chinese beliefs and traditions.

“According to Wu, infants younger than six months live in symbiosis with their mothers. They can’t tell themselves apart from the outside world. They want everything to follow their own rules. And they don’t recognize anything between the two extremes of good and bad. Wu says these three characteristics summarize the majority of Chinese people. For example, in an extended family in China, Wu writes, “Your business is my business, mine is also yours. I take too much responsibility for you, and you take too much for me. Otherwise you are a jerk, and I’ll feel guilty.” He notes in a recent interview (link in Chinese) that the phenomenon is reflected in a new hit Chinese dating show, where parents pick partners for their kids.

“From a social perspective, Wu notes, Chinese people place a strong emphasis on collectivism because they can’t live on their own, both spiritually and materially speaking. They rely on guanxi, or personal connections, to get things done. Meanwhile, they prefer to let powerful figures such as their parents or the government make decisions for them. Wu also challenges the Chinese government. He says mothers dominate Chinese families, while fathers are often missing in the role of a parent — just like Chinese rulers are absent in the role of government. “Good fathers rarely exist, and more often they are bastards having desires,” he writes. “If Chinese families can have more powerful, good fathers, our politics will perhaps be more powerful and honest.”

Individualism, Hedonism and Western Values in China

“Individualism” is a trait that is looked upon with scorn by Communist government. Showing off and promoting oneself is not widely accepted. Too much pride has traditionally been thought to attract misfortune. A Chinese skateboarder told the Los Angeles Times, “The Chinese are still traditional, and many young kids have no ambition to show themselves off.”

On woman who spent 28 years in a labor camp breaking rocks told travel writer Colin Thubron, "In China, you must conform but I can't. That's why they think I'm mad. I challenge everything, you see, and that's the madness here. I ask Why? Why?...Why is not a Chinese question."

In 2002, John Pomfret of the Washington Post wrote: “Communism as an ideology is dead. It has been replaced by hedonism...Nationalism may appeal to a few hot-headed students but it can’t compare to a night on the town with a hot hostess in a Karaoke bar...China’s energy is focused on production and consumption — not self-reflection. This country is all id and no superego. It citizens hunger for sex, food, money, goods and cheap thrills.”

Some young Chinese while away the hours drinking potent moonshine, messing around with prostitutes and indulging themselves in pot-stewed pigs ears. Youths with school bags can often seen drinking beer at restaurants or smoking while they walk to and from school. According to one survey, 30 percent of Shanghai's middle school students drink and smoke. In another survey, most college students said their goal in life was to "to make money." Parents blame the current attitude on the negative influence of movies and advertising.

The youth of China today are widely seen as sort of lost generation with nothing to believe in but money, the writer Paul Theroux wrote, "no dogma, no Mao, no gods, no emperor, no Taoism, no Buddhism...with democracy such a long shot that most students didn't bother to participate in demonstrations." A Chinese professor, who lectured his students about international relations after visiting America, was disappointed with his students who, when the lecture was over, asked him questions like what brand of cigarettes Americans smoked.

See Culture, Media, American Television shows

Changing Codes of Behavior in China

Photographer Michael Yamashita wrote in National Geographic: Along with the changes that define new China “comes a change in people’s outlook. There’s a new confidence, a sense of destiny, and such an incredible thirst for knowledge.”

Peter Hessler wrote in National Geographic, “Few Chinese spend much time thinking about the future. Decades of political turmoil taught citizens that nothing lasts forever, which inspires the fearlessness of the entrepreneurs but also makes them shortsighted.”

Peter Hessler wrote in The New Yorker, “The place changes too fast; nobody in China has the luxury of being confident in his knowledge. Who shows a peasant how to find a factory job? How does a former Maoist learn to start a business?...Everything is figured out n the fly; the people are masters of improvisation.”

Many people feel the Chinese have lost their moral compass and have become too consumed with money and materialism (See Money, Business Customs). Some see the rebirth of Confucianism and a look to Confucianism to answer questions about the meaning of life as a response to this.

The younger generation has less reverence towards traditional Chinese values than the older generation and the behavior and values of many young Chinese isn't all that different from young Westerners.

Some have argued that traditional Confucian values, which prized things like harmony, humility, honor, maintaining face, and respect for older people, are quickly being replaced by Western values which emphasize things like individualism, youth and success. Young Chinese, who were once polite and respectful to their elders, now criticize them and accuse them of being rigid and addicted to boring Beijing opera. Older people accuse young Chinese of being materialistic and undisciplined and too interested in motorcycles and casual sex.

Many Chinese crave anything new. They are fond of gadgets are very much engaged in the world of cell phones, text messaging, gaming and the Internet. The only things that limits them is money.

China's growing economy over the past few decades has led to a high degree of mobility among cities and regions, creating what the Beijing-based lawyer Chen Wei described to China Daily as a "strangers' society".

Confucianist on the Outside, Confused Inside

Kerry Brown and Sheng Keyi wrote in the South China Morning Post: “It’s a simple question: “What do Chinese people believe?” But answering it has never been easy...For all the outward confidence of the officials, the reality is that China is now in a period of vast confusion. There is no clear moral path that Chinese follow, nor an easy faith they subscribe to, no matter how powerful and materially wealthy their country becomes. Indeed, morals and faith seem to have vanished. In modern times, the government has tried to erect new sources of belief, with Confucianism taking the lead position. These days, all over the country, you can see key words from the lexicon of Confucius plastered on the walls of houses — “proper behaviour”, “rights”, “wisdom”, “fidelity”. Even planes and airports have Confucian slogans daubed over them. [Source: Kerry Brown and Sheng Keyi, South China Morning Post, November 18, 2016. “Kerry Brown is professor of Chinese politics at King’s College, London. Sheng Keyi is a Chinese novelist, and author of “Northern Girls” and “Death Fugue”.]

“But this only ends up seeming deeply ironic. While the vast majority of Chinese people are still scrimping and saving, plenty of those higher up who have become wealthy in the era of material enrichment since 1978 have multiple houses, bank accounts, businesses and lovers. Blithely talking about Confucian social order in this sort of context just comes across as empty words.

“For the government, at least, Confucianism gives great-looking outer clothing. But its real appeal to people’s hearts disappeared long ago. Most people in China have become very good at telling apart what is said and what the real meaning is underneath. They are masters of piercing through formalism to the deeper reality. The main thing now is that, while people can say what they like, they still have to guard against stepping over the many red lines strewn around the place. And those legal lines in China, the lines of the permissible, are very vague. They are becoming ever easier to step across.

“This sense of ever present danger means there is no modern Lu Xun, the great writer from the Republican era, to illuminate life with shafts of delicate irony. Intellectuals are largely silent. Lively young people on the internet use humour to handle the outside world. They describe a topsy-turvy world where reference to one thing points to another. Only, there are no easy rules of translation so at least they evade capture. In this context, where saying one thing almost invariably means you are talking about another, working out what Chinese in the 21st century believe in has become even harder. What do they have faith about?

“Chinese themselves don’t have time to think about this sort of question. They feel they are always trying to catch up with everyone else. They are too busy working out what’s true and false in the crazy world around them. They focus on the immediate world around — their homes, families, networks. Some have faith, for sure. In a few rich villages, there are churches so large they have been destroyed by the local government, with believers being persecuted. Elites in the more developed areas have started to believe in an all-powerful God, but they can’t speak their faith out openly; they just have to keep it quiet to themselves in their souls. The most you can conclude when you look at Chinese society now is that the young don’t exactly believe anything, and they are not concerned about questions of spirit or soul. For them, it’s a matter of just finding out how to do things and getting by.

“Young Japanese and Chinese writers have a big difference. Japanese do have an interest in questions of philosophy and spirit. But the Chinese write about the here and now, things right before them; they are more materialistic. That reflects what life is like for people in China. They are preoccupied with all the pressures on their immediate, material lives. Spirit, meanings and faith seem very remote. As long as there is a bit of money in their pockets, some happiness in day-to-day life, then, the presiding world view goes, people don’t need to think too much. In some ways, it is better not to...“The Chinese in the end are like this — confused dreamers. Not an easy explanation of them, but the only really precise and honest one.

Image Sources: 1) Citizens poster images, University of Washington; 2) Confucius images, Brooklyn Collage; 3) Village, Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html ; 4) Sleeping guy Beifan ; Asia Obscura

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2021