GHOSTS IN CHINA

Luo Ping ghost painting On Chinese ghosts Yale historian and China expert Jonathan D. Spence, wrote in New York Review of Books, “The English word “ghost” is not really adequate to catch the range of the Chinese term "gui" that it is meant to encompass demon, ogre, monster, and goblin, as well as the souls of the dead and their apparitions to the living.”The Chinese generally recognize three kinds of ghosts: 1) “orphaned ghosts,” who left no descendants to make offerings to them; 2) “vengeful ghosts,” who have died in an accident or have been angered by some perceived injustice and need to be appeased; and 3) “hungry ghosts,” who have been condemned to their ghostly form for some misdeeds they have done. They usually have huge bellies but small mouths and are so named because they are perpetually hungry because they can never get enough food to satisfy them.Most ghosts are regarded as women because women have traditionally been more likely to be mistreated during their lives on earth and want to seek revenge against the men that mistreated them from the otherworld after they are dead. Even today many suicidal women put on red underwear before they kill themselves because they believe it will help them seek justice from the otherworld.Many Chinese believe that ghosts reside among the living. The writer Amy Tan wrote that her father’s ghost ‘sat at our dinner table and ate Chinese food. We laid out chopsticks, and a bowl for our unseen guest at every meal.” She said there were other ghosts. “I could sense them. My mother told me I could.”

According to the Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology: The Chinese were strong in the belief that they were surrounded by the spirits of the dead. Indeed ancestor-worship constituted a powerful feature in the national faith, involving the likelihood and desirability of communion with the dead. Upon the death of a person they used to make a hole in the roof to permit the soul to effect its escape from the house. When a child was at the point of death, its mother would go into the garden and call its name, hoping thereby to bring back its wandering spirit. [Source: Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

“"With the Chinese the souls of suicides are specially obnoxious, and they consider that the very worst penalty that can befall a soul is the sight of its former surroundings. Thus, it is supposed that, in the case of the wicked man, 'they only see their homes as if they were near them; they see their last wishes disregarded, everything upside down, their substance squandered, strangers possess the old estate; in their misery the dead man's family curse him, his children become corrupt, land is gone, the wife sees her husband tortured, the husband sees his wife stricken down with mortal disease; even friends forget, but some, perhaps, for the sake of bygone times, may stroke the coffin and let fall a tear, departing with a cold smile.'

“"In China, the ghosts which are animated by a sense of duty are frequently seen: at one time they seek to serve virtue in dis-tress, and at another they aim to restore wrongfully held treasure. Indeed, as it has been observed, 'one of the most powerful as well as the most widely diffused of the people's ghost stories is that which treats of the persecuted child whose mother comes out of the grave to succour him.' “Poltergeists were not uncommon in China, and several cases of their occurrence were recorded by the Jesuit missionaries of the eighteenth century in Cochin China.

“"The Chinese have a dread of the wandering spirits of persons who have come to an unfortunate end. At Canton, 1817, the wife of an officer of government had occasioned the death of two female domestic slaves, from some jealous suspicion it was supposed of her husband's conduct towards the girls; and, in order to screen herself from the consequences, she suspended the bodies by the neck, with a view to its being construed into an act of suicide. But the conscience of the woman tormented her to such a degree that she became insane, and at times personated the spirits of the murdered girls possessed her, and utilised her mouth to declare her own guilt. In her ravings she tore her clothes and beat her own person with all the fury of madness; after which she would recover her senses for a time, when it was supposed the demons quitted her, but only to return with greater frenzy, which took place a short time previous to her death. According to Mr. Dennys, the most common form of Chinese ghost story is that wherein the ghost seeks to bring to justice the murderer who shuffled off its mortal coil."

Websites and Sources: Traditional Religion in China: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Religion Facts religionfacts.com; Folk Beliefs and Superstitions: Chinatown Connection chinatownconnection.com ; New York Times on Earthquake superstitions nytimes.com ; Old Book on Superstitions archive.org/ or Old Book PDF Fileus.archive.org/2/items ; Five Elements chinatownconnection ; I Ching Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Robert Eno, Indiana University, Chinatxt Ancient Chinese History and Religion chinatxt ; < Lucky Numbers Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; New York Times article nytimes.com ; News in Science abc.net.au ; Symbols Chinatown Connection chinatownconnection.com ; What’s Your Sign whats-your-sign.com

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: FOLK RELIGION, SUPERSTITION, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com; TAOISM factsanddetails.com; FOLK RELIGION IN CHINA: QI, YIN-YANG AND THE FIVE FORCES factsanddetails.com; RELIGION, DIVINATION AND BELIEFS IN SPIRITS AND MAGIC IN ANCIENT CHINA factsanddetails.com; GODS AND SPIRITUAL BEINGS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; ANCESTOR WORSHIP: ITS HISTORY AND RITES ASSOCIATED WITH IT factsanddetails.com; QI AND QI GONG: POWER, QI MASTERS, BUSINESS AND MEDITATION factsanddetails.com; CHINESE TEMPLES AND RITUALS factsanddetails.com; YIJING (I CHING): THE BOOK OF CHANGES factsanddetails.com; CHINESE ZODIAC AND LUCKY BIRTH YEARS factsanddetails.com; SYMBOLS AND LUCKY NUMBERS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; IDEAS ABOUT DEATH, GHOSTS AND THE AFTERLIFE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; FORTUNETELLERS, DIVINATION, AND SUPERSTITION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Ghosts and Religious Life in Early China” by Mu-Chou Poo Amazon.com; “The Ghost Festival in Medieval China” by Stephen F. Teiser Amazon.com; “Chinese Ancestor Worship: A Practice and Ritual Oriented Approach to Understanding Chinese Culture” by William Lakos Amazon.com; “Chinese Religion in Contemporary Singapore, Malaysia and Taiwan: The Cult of the Two Grand Elders” by Fabian Graham Amazon.com; “The Funeral of Mr. Wang: Life, Death, and Ghosts in Urbanizing China” by Andrew B. Kipnis Amazon.com; “Death Ritual in Late Imperial and Modern China” by James L. Watson and Evelyn S. Rawski Amazon.com

Ghosts and Spirits in Traditional China

Luo Ping ghost painting Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “It may seem odd that the ancient Chinese were concerned about ghosts starving. Early Chinese notions of the spirit world were very different from those evolving in Europe; they were also unsystematic. In the Classical era of the late Zhou, the spirits of the dead were conceived as inhabiting a variety of spaces. They could be pictured in heaven, which was up, or in the region of the Yellow Springs, which was down, or as occupying the same space as humans, which was scary. Sometimes, these spatial ideas were related to a notion that humans possessed two types of death-surviving entities: one rose upon death and tended to be thought of as a benign spirit, and one descended into the earth as a spirit which could possess frightening tendencies, but was not necessarily threatening. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu /+/ ]

“Spirits of the dead were very different from the living, but were not a-physical and did require sustenance. This sustenance was the responsibility of their descendants, and was maintained through regular sacrifices of food and drink. Spirits “descended” at the time of such offerings and partook of the food, although their particular physical needs were tenuous enough that no apparent change in the offerings would appear, and apart from certain unpalatable ritual items, the “leftovers” were consumed by the thrifty clan members, an act which was itself viewed as pious. Ancestral spirits took a great interest in the affairs of their descendants, and their influence varied according to their lifetime temperaments, any crotchets which they may have picked up through the unpleasant experience of death, their judgments of the conduct of the descendants, and the quality of the sacrificial menu. As ancestors grew more remote, their impact grew more tenuous, and if they continued to exist, their existence was such that they no longer required further human attention – only recent ancestors showed up at dinnertime. The relatively tame ancestral spirits shared an influence on the course of human events with a host of much more interesting animal demons, nature gods, city gods, anonymous revenants, and unidentified spooky things, all of which made the nighttime good to sleep through and Chinese religious beliefs colorfully incoherent. /+/

“Kings were different. For the Zhou, if they died peacefully they went up to heaven where they were seated to the left and right of the “Lord on High,” an anthropomorphic high deity roughly equivalent to Tian, the term we translate as Heaven. The former kings of the Zhou ruling house remained important to the political health of the realm, but spiritually unproblematic. The Shang view of former rulers was more complex, but we will encounter those only later in the course, as the writers of Classical China were no longer aware of them.”/+/

Family, Ghosts and Religion in Traditional China

Exorcism in the 1920s

Dr. Eno wrote: “Early China’s family-centered orientation was expressed in religious practice. Although ancient Chinese society included a wide variety of religious cults and practices, the most basic of all religious activities was the family cult known as ancestor worship. People in ancient China believed in a type of life after death. In their view, certain components of the person — including aspects of consciousness, physical needs, and worldly powers — did not cease to exist with death, but persisted for generations in a semi-physical state. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu /+/ ]

“Ghosts of the dead continued to inhabit the local space of their former homes, continued to need physical sustenance in the form of food and drink, and possessed the ability to influence events in the world. It was the duty of the lineal descendants of these ghosts — their sons and grandsons — to provide regular nourishment in the form of sacrificial foods and drink, and to behave in ways that accorded with the good examples set by former generations. If lazy children allowed dead ancestors to go hungry or brought disgrace to their names, ancestors had the power to wreak vengeance. On the other hand, dutiful fulfillment of ritual sacrifices, respectful salutations of the dead, and upright social behavior by descendants would attract the blessings of ancestors, who had the power to provide protection and bestow rewards. /+/

“The most regular form of religious activity for every person in ancient China was the offering of scheduled sacrifices to one’s ancestors. These rituals occurred in homes at every level of society. Among the privileged classes, elaborate ancestral halls served as religious centers for extensive clans. The most aristocratic of clans were entitled to construct large walled temple complexes devoted exclusively to the ancestors of their clan.” /+/

Ghost Month in China

Ghost Month, or Hungry Ghost Month, begins on the full moon of the seventh month of the lunar calendar, usually around mid August, and lasts for 15 days to a month. It is a time when some Chinese believe spirits get a "summer vacation" from the other world and return to the mortal world to cause mischief and enjoy feasts, performances of Chinese opera and other activities. Firecrackers are set off to scare away dangerous ghosts while ancestors are welcomed with bonfire offerings and recitations of Buddhist scripture.

Chinese go out of their to be nice to ghosts and go about their activities with more caution than usual. Many people avoid traveling, moving into new homes, opening businesses, or getting married because ghosts associated with these endevours could cause mischief. People who die during Ghost Month are sometimes stored and buried when Ghost Month is over.

Businessmen dread Ghost Month because people are often reluctant to buy anything; partiers stay home; wives orders their husbands to come home straight form work; and tourists stay away from beach resorts out of fear of being captured by ghosts in the water. The ghost month in 2006 was particularly nasty because it was a calender year with two seventh months, when the gates of hell open and the dead walk among the living twice.

Spirits are placated with k’o t’ous (bows), prayers, offerings of chicken, pork, rice spirits and wine, and banquets and operas. Buddhists sutras are chanted to transfer merit to the dead and 2.5-meter candles are lit to honor them. After sunset many people make small fires and burn incense, paper televisions, paper Rolexes, paper cell phones, paper Mercedes Benzes and wads of “hell money” to appease the ghosts and encourage them to bring about good fortune. An old saying goes: "The bigger the flame, the better your luck will be."The offerings and burnings can take place at the graves of ancestors but are usually directed towards ‘soul tablets” of the deceased in homes and temples. Buddhist monks and Taoist priests are hired to conduct special rituals to placate “hungry ghosts.”Operas featuring ghosts are fixtures of Ghost Month, especially in Hong Kong. Explaining the purpose of an opera for ghosts one Hong Kong theater owner told Reuters, "This show is for the gods and the ghosts, but humans can come and watch too...What we're doing is telling the ghosts to leave us alone, not to create trouble or frighten our neighbors and kids." Empty chairs are set out for ghosts.Ghost Month is a Chinese holiday celebrated mostly by Chinese in Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia, and Hong Kong although it is making a come back in China even though it has been denounced by the government as foolish superstition.

See Separate Article HUNGRY GHOST MONTH factsanddetails.com

Renderings of Chinese Ghosts

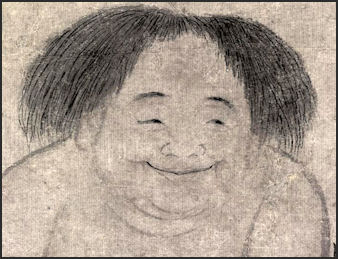

Luo Ping ghost painting Luo Ping was an 18th century Chinese artist who specialized in rendering ghosts. Spence wrote: “Luo Ping was not only innovative in “portraying” his ghosts with such specificity, he kept the element of surprise constantly to the fore...In the third section of his Ghost Amusement portrayed an absorbed amorous couple in unmarred human form, gazing into each other's eyes, while a man in the tall white hat of the underworld's guardians prepared to lead the couple into the netherworld. The woman's bared red shoes offered the viewer a signal that was, for the times, shockingly erotic. After four more panels of the magically displayed ghost figures, the eighth and final panel would have come with a startling force to the unprepared viewer — as two complete skeletons were portrayed standing tall and opposite each other in a clump of bare trees, dark rocks, and wild grasses. The precisely delineated specificity of these figures did not convey an auspicious message, but instead closed the scroll on a somber more than a mysterious note.” [Source: Jonathan D. Spence, New York Review of Books, in connection with Eccentric Visions: The Worlds of Luo Ping (1733-1799): an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, October 6, 2009, January 10, 2010]

In one series of Luo Ping scrolls he art historian Yeewan Koon wrote: “Half naked with bald pates and small swollen stomachs, the two figures also recall the world of hungry ghosts, one of the Buddhist realms of existence. But the human emotions on the faces of Luo's ghosts place them in a gray consciousness that lurks between the real and the otherworldly. In this painting, Luo has created an ethereal existence by making his ghosts both strikingly familiar, through their human pathos, and evocatively strange,through their physical deformities.

Koon wrote: “The second leaf is a contrast of types: a skinny, bare-chested ghost with an official's hat follows a fat, bald ghost in tattered clothes against an empty background. The oscillation between specificity of types and ambiguity of situation allows room for a range of interpretations; some viewers were prompted to read this scene as phantasmagoric social commentary. [One scholar], for example, a Hanlin academician and playwright, described the figures in leaf 2 as a “slave ghost” and his master, whom he then compared to corrupt Confucian officials.

This “urge to rationalize the ghosts as allegories of human behavior,” adds Koon, “is derived in part from the theatrical immediacy of the images,” and in this sense the ghost paintings catch the tensions and contrasts that were coming to dominate this time in China's history — as well as the layers of religious euphoria that lay behind the alternate reading of the scrolls title as a “realm of ghosts,” a literalness of interpretation that Luo Ping deliberately fostered by his repeated claims that he had seen the ghosts in person on many occasions. This claim, writes Koon, was a part of Luo Ping's “invented persona as an artist who saw and painted ghosts,” a persona that ‘set him apart in a capital teeming with talent.”

See Separate Article CHINESE PAINTINGS OF GHOSTS AND GODS factsanddetails.com

Ghosts and Pearl S. Buck

Luo Ping ghost painting

In her biography "Pearl Buck in China: Journey to The Good Earth" Hilary Spurling wrote: Pearl Sydenstricker was born into a family of ghosts. She was the fifth of seven children and, when she looked back afterward at her beginnings, she remembered a crowd of brothers and sisters at home, tagging after their mother, listening to her sing, and begging her to tell stories...The siblings who surrounded Pearl in these early memories were dreamlike as well. Her older sisters, Maude and Edith, and her brother Arthur had all died young in the course of six years from dysentery, cholera, and malaria, respectively. Edgar, the oldest, ten years of age when Pearl was born, stayed long enough to teach her to walk, but a year or two later he was gone too (sent back to be educated in the United States, he would be a young man of twenty before his sister saw him again). He left behind a new baby brother to take his place, and when she needed company of her own age, Pearl peopled the house with her dead siblings. “These three who came before I was born, and went away too soon, somehow seemed alive to me,” she said.” [Source: "Pearl Buck in China: Journey to The Good Earth" by Hilary Spurling (Simon & Schuster, 2010)]

“Every Chinese family had its own quarrelsome, mischievous ghosts who could be appealed to, appeased, or comforted with paper people, houses, and toys. As a small child lying awake in bed at night, Pearl grew up listening to the cries of women on the street outside calling back the spirits of their dead or dying babies. In some ways she herself was more Chinese than American. “I spoke Chinese first, and more easily,” she said. “If America was for dreaming about, the world in which I lived was Asia. I did not consider myself a white person in those days.” Her friends called her Zhenzhu (Chinese for Pearl) and treated her as one of themselves. She slipped in and out of their houses, listening to their mothers and aunts talk so frankly and in such detail about their problems that Pearl sometimes felt it was her missionary parents, not herself, who needed protecting from the realities of death, sex, and violence.”

‘she was an enthusiastic participant in local funerals on the hill outside the walled compound of her parents' house: large, noisy, convivial affairs where everyone had a good time. Pearl joined in as soon as the party got going with people killing cocks, burning paper money, and gossiping about foreigners making malaria pills out of babies' eyes.”

Chinese Spirits

Spirits of five planets

The writer and dissident Liao Yiwu met one man in prison who was there because he burned is wife alive, convinced he was possessed by an evil dragon. The man converted to Christianity and prayed everyday, “hoping that evil dragon will not come back and harm people again.”

Some villagers say that ghost no longer exist because Mao got rid of them in 1957. Even so, to hedge their bets perhaps, they wear charms with clusters of old coins. “The more coins the more you can avoid unclean ghosts,” one village women told the writer Amy Tan. Many Chinese believe in animals spirits. The fox spirit is particularly well known. So too are the rabbit and snake. Some people protect their house from the fox’s influence with a circle incense.

Many Chinese believe that certain people have the ability ro see the spirit world. Clairvoyants are called "mingbairen", “those who understand.” They were discouraged in the Mao era but have made a comeback in recent years.

Chinese Ghostbuster at Work

Describing a Chinese ghostbuster at work in Singapore, Philip Lim of AFP wrote: “The corner looked empty...”There's an old woman standing there, wearing an old blue dress, and she has curly hair,” professional exorcist Chew Hon Chin told his stunned client in the brightly-lit living room. “Let's ignore her for now. Let me clear your house of dirty stuff first and I'll move her out later,” the 64-year-old Chew told housewife Zhang Qiao Zhu, who hurriedly led him to one of the flat's bedrooms.” [Source: Philip Lim, Agence France-Presse, February 12, 2011]

“Inside, the stern-faced Chew produced a pair of metal rods bent at a 40-degree angle, stared at the black balls swaying gently at each end and finally pointed to a closed cupboard. “There is a blue towel with a striped pattern inside,” Chew told Zhang in Mandarin. “Take it out and remove it from the room.” Zhang, 56, complied meekly, not questioning Chew's pronouncements or his apparent ability to peer through closed wardrobe doors to identify "tainted" objects within.”

“Chew exorcises ghosts and repels curses for a living, and the word "Ghostbusters" is spelled out in English in a red sign with gold lettering above the entrance to his shop. Zhang called him when she sensed there was something strange in her neighbourhood, or more specifically her house, after feeling someone — or something — choking her every night whenever she tried to sleep.”

“On a another house call, Chew used his metal rods to pinpoint what he said was the spirit's location, then flung coarse salt into a small bronze urn filled with burning charcoal. A helper tossed in onion skins to produce an acrid burst of smoke. “Ghosts are afraid of this smell, when the salt crackles it's like an explosion to ghosts and they will run,” Chew said confidently.” Later he took his clients to a quiet clearing in suburban Singapore, where he lit a ring of fire around them and instructed them to step over it. After the ritual, the clients were soaked in a tub of herb-spiced water. “Fire burns away all the evil from your body, water cleanses the soul,” Chew said.”

Luo Ping ghost painting

China Ghostbuster’s Story

“Chew — a BMW-driving former nightclub owner — said business was good in predominantly ethnic-Chinese Singapore, where religion and superstition remain deeply rooted despite mass affluence. Chew, who says he handles three to four cases a day, offers services from "luck enhancement" costing 88 Singapore dollars (68 US) to "deceased appeasement" at "100 dollars per soul" — although more difficult spirits command prices reaching into the thousands.” [Source: Philip Lim, Agence France-Presse, February 12, 2011]

“Chew said he acquired his skills after being cured of a curse placed by a vengeful former employee whom he had sacked. He vomited blood, mosquitoes and metal filings for more than 10 years, Chew claimed. After his recovery, Chew said the supreme Taoist deity known as the Jade Emperor visited him, made him a "godson" and told him the secrets of divining and exorcism, which entailed 108 days of meditation on a deserted island in neighbouring Indonesia.”

“Today he says has a kind of sixth sense. "I have the eye of the heavens — when you come into my office I can immediately see the bad things behind you," the devout Taoist told an AFP reporter, pointing to the supposed location of a "third eye" on his forehead. Chew said this enhanced vision allows him to detect malevolent energy emanating from specific items which he describes in painstaking detail to customers visiting his shop.”

“Chew's shop, situated in a shopping mall a 15-minute drive from the financial centre, also doubles as a ghostly jail, with sealed plastic "cells" containing objects discovered during his work lining a wall beside an elaborate altar to the Jade Emperor. Vials containing dark liquids, macabre finger-sized dolls and wooden carvings of faces beneath an ominous sign saying: “Nice to see, fun to touch. Once broken, more business for us!” Chew was sanguine about his close proximity to the spirit world, "As a policeman or soldier, I should not be afraid of criminals or war. As a ghostbuster, I should definitely not be afraid of ghosts, in fact ghosts should be afraid of me!"

Ghost Marriages in China

In Chinese tradition, a ghost marriage (in Chinese "spirit marriage") is a marriage in which one or both parties are deceased. Chinese ghost marriage was usually set up by the family of the deceased and performed for a number of reasons, including: the marriage of a couple previously engaged before one member’s death, to integrate an unmarried daughter into a patrilineage, to ensure the family line is continued, or to maintain that no younger brother is married before an elder brother. Other forms of ghost marriage are practiced worldwide, from Sudan, to India, to France since 1959. The origins of Chinese ghost marriage are largely unknown, and reports of it being practiced today can still be found.[Source: Wikipedia]

Ghost marriages are often set up by request of the spirit of the deceased, who, upon "finding itself without a spouse in the other world," causes misfortune for its natal family, the family of its betrothed, or for the family of the deceased’s married sisters. "This usually takes the form of sickness by one or more family members. When the sickness is not cured by ordinary means, the family turns to divination and learns of the plight of the ghost through a séance."

More benignly, a spirit may appear to a family member in a dream and request a spouse. Marjorie Topley, in "Ghost Marriages Among the Singapore Chinese: A Further Note," relates the story of one fourteen-year old Cantonese boy who died. A month later he appeared to his mother in a dream saying that he wished to marry a girl who had recently died in Ipoh, Perak. The son did not reveal her name, but his mother used a Cantonese female spirit medium and "through her the boy gave the name of the girl together with her place of birth and age, and details of her horoscope which were subsequently found to be compatible with his."

Because Chinese custom dictates that younger brothers should not marry before their elder brothers, a ghost marriage for an older, deceased brother may be arranged just prior to a younger brother’s wedding to avoid "incurring the disfavour of his brother’s ghost." Additionally, in the days of immigration, ghost marriages were used as a means to "cement a bond of friendship between two families." However, there have been no recent cases reported.

See Separate Article GHOST MARRIAGES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: University of Washington; United College in Hong Kong; Luo Ping ghost painting from the Met in New York, Nelson-Atking Museum, Ressel Fok collection; Asia Obscura

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2021