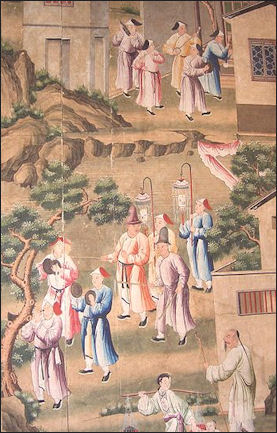

CHINESE FUNERAL PROCESSION

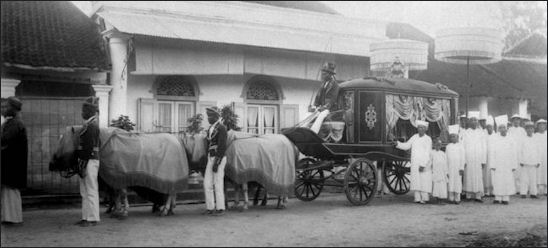

funeral procession On a day and time selected by the feng shui master or a diviner the coffin is carried to a cemetery or burial place in an elaborate funeral procession. The route is lined with lanterns to ensure the deceased doesn’t get lost. Sometimes the coffin is a carried in a hearse decorated with dragons, an ancient symbol of good luck. Other times it is carried by pallbearers on a bamboo litter, preceded by an empty chair for the deceased to sit so he can join the procession.

Funeral processions are associated mostly with funerals in northern China. Some are quite involved, featuring men throwing around spirit money, displaying written testimonials to the deceased, carrying plaques with teh deceased's titles and official posts, and bringing items for grave side sacrifices. Behind them are musicians, monks, priests, the chief mourners, pallbearers carrying the coffin, women and children.

The procession is often led by family members of the deceased who carry incense and portraits of the deceased and often are dressed in a precise manner which defines their closeness to the deceased. A traditional brass band and professional mourners often accompany them. The procession usually moves slowly and stops at roadside alters to allow offerings to be made and at the birthplace, home and other places associated with the deceased. In some places memorial arches are erected across a street to commemorate fulfilled and loyal deeds and remind passers by to revere morality and values.

Describing a procession John Pomfret wrote in the New York Times: The “casket was slid into a colorful canopy, festooned on each side with the images of four Taoist saints...Twelve laborers, hired for the task, lifted the contraption onto their shoulders. Two men with bags of firecrackers began tossing packets of their bombs, designed to scare off harmful ghosts. Before our final ascent to the burial site, we halted at an intersection. We made a circle around the casket and kowtowed, one by one, placing straw, knotted expertly by an elderly neighbor, under our knees. Three times were circled the casket: three times we kowtowed.”

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: FOLK RELIGION, SUPERSTITION, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com; FOLK RELIGION IN CHINA: QI, YIN-YANG AND THE FIVE FORCES factsanddetails.com; RELIGION, DIVINATION AND BELIEFS IN SPIRITS AND MAGIC IN ANCIENT CHINA factsanddetails.com; GODS AND SPIRITUAL BEINGS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; ANCESTOR WORSHIP: ITS HISTORY AND RITES ASSOCIATED WITH IT factsanddetails.com; CHINESE TEMPLES AND RITUALS factsanddetails.com; YIJING (I CHING): THE BOOK OF CHANGES factsanddetails.com; FENG SHUI: HISTORY, BUILDINGS, GRAVES, HOMES, BUSINESS AND LOVE factsanddetails.com; FENG SHUI, QI AND ZANGSHU (THE BOOK OF BURIAL) factsanddetails.com; CHINESE GHOSTS factsanddetails.com; IDEAS ABOUT DEATH, GHOSTS AND THE AFTERLIFE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN FUNERALS, SKY BURIALS AND VIEWS ON DEATH factsanddetails.com FUNERALS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; GRAVES, BURIALS AND CREMATIONS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; Websites on Funerals and Death: Chinese Beliefs About Death deathreference.com ; Death and Burials in China chia.chinesemuseum.com.au

RECOMMENDED: Video: “Dancing for the Dead: Funeral Strippers in Taiwan” Amazon.com Books: “Buddhist Funeral Service” (Chinese Buddhism Book) by Ven Hong Yang Amazon.com; “The Funeral of Mr. Wang: Life, Death, and Ghosts in Urbanizing China” by Andrew B. Kipnis Amazon.com; “Death Ritual in Late Imperial and Modern China” by James L. Watson and Evelyn S. Rawski Amazon.com; “Funeral” (Chinese Folklore Culture) by Sangzhang Juan Amazon.com; “Chinese Funeral Practices - What's Right for the Christian?” by Daniel Tong Amazon.com

Chinese Funeral Entertainment

Traveling folk opera troupes often perform comedy skits and sing arias at funerals. The head of one such group, that performed on the flat bed of an old jury-rigged trucks with loudspeakers, told National Geographic that 80 percent of his business was at funerals. He said, “Of course I’m sorry for the family but this is my living.”

The troupe leader’s business card read: “Zhang Baolong/ Feng Shui Master/Red and White Events: Services of the Entire Length of the Dragon, From Beginning to the End.” Among the 27 services listed on the back of the card were “choosing grave sites,” “choosing a marriage partner,” “house construction,” “towing trucks,” and “evaluating locations for mining.” [Source: Peter Hessler, National Geographic]

Funeral music is designed to soothe the spirit of the deceased and usually is in the form of high pitch piping from an oboe-like instrument played by a paid musician and percussion from cymbals, drums and gongs played by priests and monks. Music often accompanies key parts of the funeral. Under the Communists, brass bands and military uniforms were added to funerals.

Extravagant Funerals in China

Confucius urged people to have low key funeral rituals. Before the Communist era, elaborate funerals were common and were regarded as a respectful way to send off the dead. Lin Yutnag, a 20th century scholar, wrote: “There is no reason to be solemn. Even today, I can’t tell the difference between the rituals of a funeral and a wedding until I see a coffin or a bridal sedan chair.”

After Mao came to power extravagant funerals were considered a collasal waste of money and resources and were discouraged and condemned as superstitious and a results ill-gotten gains.

In receny years, ostentatious funerals have made a comeback. As incomes have increased so too have spending on funerals. These days it is not unusual for a family to spend the equivalent of several years income on a lavish funeral. The funeral industry is now regarded as one of the 10 most profitable businesses in China.

In August 2006, police in Jiangsu Province arrested five women from a “dance troupe” who danced naked and did a striptease in a send off for dead farmer. The entertainment might have served to help attract a crowd. Traditionally, rural people, especially, believed that the more people that showed up at a funeral the mor ehonor was bestowed on the deceased.

Funerals have traditionally served as way to pay bribes and influence people. In the old days it was common to give envelopes stuffed with cash and gold models of the birth animal of the deceased to the deceased's family. A law passed in the mid 2000s banned officials from inviting all but their closest relatives to funerals to reduce corruption by cracking down on the practice of passing cash-filled envelopes as bribes.

Taiwanese Funerals and Copyright Fees

Jens Kastner wrote in the Asia Times: “The back alley in Taipei's satellite city is closed to traffic... The tent's entry is decorated with orange wreaths, and gifts for the afterworld are displayed: beer pallets and models of a villa and a Mercedes Benz made of cardboard. The mourners sit on simple folding benches, the deceased man's coffin placed in front of them. [Source: Jens Kastner, Asia Times, April 20, 2010]

A subtle tension is perceptible when the funeral director starts tinkering with the widescreen flat-panel monitor in the corner. Seconds later, images depicting the deceased in his lifetime appear in a photo stream, and a pre-mortem recorded voice wishes a “Thank you for coming, I wish you all live to 120 years.” Incense smoke and the tunes of Willie Nelson's "You Are Always on My Mind" fill the tent.

This is how Taiwanese say farewell to the dead. But copyright protectors are now crying foul play to the popular use of memorial CD-ROMs, saying it infringes intellectual property rights (IPR), and mourners ought to pay up. Taiwan's zealous IP protectors claim that although police raids on funeral ceremonies are unlikely, the law is clearly being broken. This is especially the case when the deceased's favorite songs are placed on blogs or photo-sharing websites as is commonly done. In the past, Taiwan has been reputed for rampant copyright piracy, but the controversy over the memorial CD-ROM implies that times have changed.

Producers of memorial CD-ROMs advertise that songs chosen by the dead played at the funerals bring emotions to a climax. “To deliver quality work isn't child's play,” Chen Kai-wen who markets his services online points out. “Presenting a whole life in a few minutes to the satisfaction of the bereaved requires skill.” Some families would hand Chen hundreds of pictures, others only 10. Either way it doesn't work out because the amount of photos needed for an excellently made memorial CD-ROM should be around 30 per song. Otherwise the photo stream would become too boringly slow or, even worse, too hectic.

In Chen's eyes, Taiwanese morticians and CD producers both do a great job to soothe the bereaved relatives' emotional pain, and he also understands the necessity for the collection of copyright fees. Chen promises: “In future we will encourage the grieving families to be creative and use music they have recorded themselves. If they still insist on playing protected songs, I think it should be up to the morticians to pay the bill.”

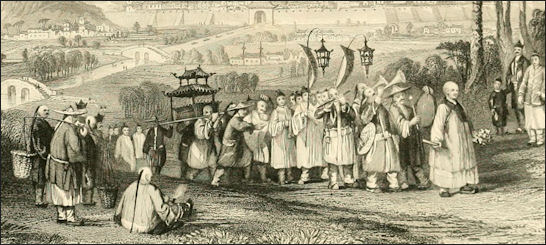

funeral procession the 1920s

Professional Mourners in China

Chen Ning wrote on Danwei.org : “Wailing is an ancient funeral custom. Texts show that dirges began to be used in ceremonies during the time of Emperor Wu of Han and became commonplace during the Northern and Southern Dynasties. Customs varied across ethnicities and regions. During the Cultural Revolution, wailing was viewed a pernicious feudal poison and went silent. In the reform era, it was revived in a number of areas.” [Source: Chen Ning, TBN, Danwei.org July 23, 2010]

The funeral performance industry reportedly started to take off in Chongqing and Sichuan around 1995. In 1992, the city of Chongqing imposed a ban on fireworks, which left funerals lacking an important Ceremonial feel and led indirectly to the rise of funeral performances. According to Chongqing media, the industry had nearly 100,000 practitioners at its height. By 2002, Chongqing issued the Regulations on Management of Funeral Services, which did not permit [wailing] bands to perform within the urban area. Urban funerals could be held in funeral halls that were set up in each administrative district...This had a huge effect on the profession and led to the breakup of many bands. Subsequently, the industry was pushed to the margins, at the edge of the city or in rural towns and villages.

“In Chongqing and Chengdu, wailers and their special bands have, over the course of more than a decade, developed into a professional, competitive market. Studies show that wailers are predominantly laid-off workers. To support themselves, they rely on weeping and melancholy songs for their income. They and their bands believe that, like everyone else, they are engaging in a profession and performing a job.”

Typically, wailers will bring to mind their own experiences to make themselves cry. Professional wailer Jin Guorong says that the first time she performed she was scared of not being able to cry, but when she thought of how she was in the profession despite being afraid of dead people, and how difficult it had been to go into business for herself, she wept hysterically...For a wailer, sobbing, covering the face, and kneeling on the ground are all techniques to increase the effect of the performance.

Reportedly, women make up the majority of wailers, and their husbands are usually in the same profession... Jin Guorong say that in their industry, resentment is hard to avoid. When they get together, friends who come over to greet them will frequently find some excuse to leave immediately. “I know that they don’t want to sit near us... People look down on us, but we don’t look down on ourselves,” says Jin Guorong. “When we perform, we call each other by respectful titles. For example, the MC will say, “Let’s invite Teacher so-and-so to perform the next item on the program.”

The wailers are typcally members of bands that also play songs and perform skits. The bands do funerals in the evenings, but during the day they sometimes take on weddings. Most of them do their best not to let people know that they are wailers. When working a funeral roles have to be changed quickly. Weeping is necessary during the wailing portion, but afterward they have to pull themselves together and enter another mode of performance, which might be a comic skit. From tears to laughter, just like face-changing in a Sichuan opera.

Story of a Modern Professional Chinese Mourner

Chen wrote about, 52-year-old professional wailer and bandleader named Hu Xinglian, who is known as one of the ten great wailers of Chongqing. Before the ceremony begins, she asks the family of the deceased about the situation. She wears her hair in pigtails and puts on white mourning clothes and makeup because she believes that makeup shows respect to the bereaved family. During the eulogy, Hu Xinglian sometimes howls dad or mom to create a melancholy atmosphere for the family. [Source: Chen Ning, TBN, Danwei.org July 23, 2010]

Hu says that fees usually run between 200 and 800 RMB (US$30-118) per performance. Tonight the fee is 200 RMB. Taking out 70 RMB for the agency leaves the six members of the band with 130 RMB. The agency fee is given to the wreath shop. Hu explains that as the industry has grown, shops selling funeral products, which engage the families of the deceased directly, have become middlemen for the bands. And as bands have become more numerous, wreath shops have developed into one-stop providers of all funeral-related services. The band is just one link in the shop’s comprehensive service chain.

Most of Hu’s business these days comes from the wreath shop. In addition to the fee they charge for their performance, wailers receive gratuities. In Chongqing, once the wailing ceremony has concluded, the bereaved will pick up the wailer and hand over a bouquet that contains some money. In Chengdu, they put small red envelopes beside the wailer as the wailing is in progress. Hu says that tips vary widely, from a few yuan to several hundred.

Professional Mourners at Work

Describing Hu at work at a funeral for an old man in a small neighborhood in of Baiyun in Jiangbei District, Chongqing, Chen wrote: “At around 7:30, Hu calls the family of the deceased into the mourning hall and begins to read the eulogy. There is a formula to the eulogy that is adapted to the particular circumstances of the deceased. Most of these say how hard-working and beloved the deceased was, and how much they loved their children. The eulogy requires a sorrowful tone and a rhythmic cadence. As Hu reads, she sometimes howls dad or mom. And then the bereaved begin to cry as they kneel before the coffin.

After the eulogy comes the wailing, a song sung in a crying voice to the accompaniment of mournful music. Hu says that the purpose of this part is mainly to create a melancholy atmosphere which will allow the family to release their sadness through tears. Because of the special status of the deceased at this particular funeral, the family members have requested that the wailing portion be eliminated.

Hu says that more time is devoted to wailing in the countryside. In video recordings, Hu can be seen howling, weeping with her eyes covered, and at times crawling on the ground in front of the coffin in an display of sorrow. At some funerals, she crawls for several meters as she weeps. This never fails to move the mourners. As she wails, the family of the deceased sob, and some of them weep uncontrollably.

After the wailing is done, the second part of the funeral performance begins. Hu says that a funeral performance is usually sad in the beginning and happy at the end. Once sorrow has been released through tears, then the bereaved can temporarily forget their sorrow through skits and songs. This segment was once the domain of the suona, drum, and Sichuan opera, but now it has developed into songs, skits, and even magic acts...On this occasion, at the family’s request, she has cancelled the skits and just has a few singers sing songs. Shortly after this segment begins, family members begin to leave. Hu and her band sing a few songs and then end their performance: If the bereaved think it’s important, we will too. If they don’t care, we won’t care either.

When the funeral performance concludes...it is time for the spectators to request songs. Hu changes into a floral dress and sings and dances with the performers on stage, to occasional cheers from the audience. This segment is a money-maker for the band: it costs 20 RMB to request a song. In Chongqing, bands reportedly rely on requests for most of their income. That evening, Hu Xinglian’s band makes 700 RMB on song requests. Every member gets 110 RMB, and after expenses, she is left with 130.

Making a Living as Professional Mourner

Divorced, looking after her parents and child on her own, Hu Xinglian could not support herself on her salesperson’s salary, so she began a second job as a wailer...She says that the performance is draining to both mind and body. When she wails, she says, “My hands and feed twitch, my heart aches, and my eyes go dim.. Wailing has more lasting effects, too: Hu says that her hands have gone numb from time to time over the past year.

According to her own count, she has wailed for more than 4,000 people. She no longer sheds tears when she wails, but lets her voice and expression do the work instead...Hu Xinglian gathers her emotions together before she wails to look for something in the deceased’s story that resonates with her and connects to details of her own life. When she can’t cry, she will adopt a sobbing tone in her voice.

She recalls that she was terrified the first time she performed. That night, her head was filled with mournful music and she did not sleep a wink. She had never attended a funeral before. In Chongqing, Hu Xinglian was laid off in 2003, at which point she entered the funeral performance industry full-time as a professional wailer. CI had no other choice. It was the only thing I could do. 14

Hu Xinglian has special wailer’s clothes of her own design. For the past few years, her costume has changed significantly. She says that she has tried many new things since she started wailing. She has designed wailing clothing that copies costumes from TV dramas, and has created wailing songs by adding her own words to excerpts from traditional operas. She hopes that people will remember her, and hopes that more people will request her.

Hu Xinglian feels that so long as the bereaved approve, and so long as she can make money to support her family, she figures she is a success. Nothing else matters. As the industry becomes more regulated and competition becomes more fierce, Hu Xinglian feels that the market will be harder to handle, and she worries about the future....Hu says that her income is less than that, just 5,000-6,000 RMB. She says that she cannot afford old-age insurance and cannot meet medical insurance payments.

Funeral Strippers in China

Strippers were sometimes hired to work at funerals in China According to the Wall Street Journal’s China Real Time: “The point of inviting strippers, some of whom performed with snakes, was to attract large crowds to the deceased’s funeral – seen as a harbinger of good fortune in the afterlife. “It’s to give them face,” one villager explained. “Otherwise no one would come. The mainland isn’t alone in its preference for the practice: similar ensemble performances are also popular in Taiwan – as National Geographic documented in 2012, with stilettoed, short-skirted women dancing graveside. The practice there dates back decades. [Source: China Real Time, Wall Street Journal, April 23, 2015]

Euan McKirdy and Shen Lu of CNN wrote: “In rural China, hiring exotic dancers to perform at wakes is an increasingly common practice. “In some areas of China, the hiring of professional mourners, known as "kusangren" is commonplace. These can include performances, although in recent times the dance acts have increasingly tended towards the erotic. Strippers are invited to perform at funerals, often at great expense, to attract more mourners, China's official Xinhua news agency said. Another report suggested another motivation: that the performances "add to the fun." [Source: Euan McKirdy and Shen Lu, CNN, April 24, 2015]

“Photos obtained by CNN from an attendee at a village funeral in Cheng'an County in Hebei Province show mourners of all ages, including children, watching the performance. The attendee, who asked not to be identified, said he was visiting family during the Lunar New Year holiday. While he was there, one of the elderly villagers died so he went to the funeral. "I felt something wasn't right," he told CNN. "The performance crossed the line. I had heard about hiring strippers to dance at funerals but had never seen it myself. I was shocked when I saw the strippers." He said the villagers said this kind of performance had been practiced for a while. "They didn't find it shocking or strange. They were used to it. "They told me, 'what if we can't watch (this kind of) performance after it gets exposed by the media?'"

In August 2006, police in Jiangsu Province arrested five women from a “dance troupe” who danced naked and did a striptease in a send off for dead farmer. The entertainment might have served to help attract a crowd. Traditionally, rural people, especially, believed that the more people that showed up at a funeral the more honor was bestowed on the deceased.

Funeral Strippers in Taiwan

Taiwan's funeral strippers work on Electric Flower Cars (EFC) which are trucks that have been converted to moving stages so that women can perform as the vehicles follow along with funerals or religious processions. EFC came to Taiwan's public attention in 1980 when newspapers began covering the phenomenon of stripping at funerals. [Source: Krista Van Fleit Hang]

There is a great deal of debate about whether this should be allowed to continue. In Taipei, Taiwan's capital, one often hears middle and upper class men complain about the harmful effects of this rural practice on public morality. In contrast, people in the industry see themselves as talented performers and fans of the practice say that it makes events more exciting.

"Dancing for the Dead: Funeral Strippers in Taiwan" directed by Marc L. Moskowitz is a 38-minute film about the custom in Chinese and English with English subtitles. The film follows this story, providing interviews with Taiwan's academics, government officials, and people working in the EFC industry to try to make sense of this phenomenon. The film includes footage from nine different cities across Taiwan, including EFC performances, a funeral, and several religious events. Moskowitz is an Associate Professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of South Carolina. [Video people.cas.sc.edu/moskowitz ]

Ban on Funeral Strippers in China

In April 2015, the Wall Street Journal’s China Real Time reported: “In China, friends and family of the deceased may have to do without strippers. “According to a statement from the Ministry of Culture on Thursday, the government plans to work closely with the police to eliminate such performances, which are held with the goal of drawing more mourners. [Source: China Real Time, Wall Street Journal, April 23, 2015]

“Pictures of a funeral in the city of Handan in northern Hebei province last month showed a dancer removing her bra as assembled parents and children watched. They were widely circulated online, prompting much opprobrium. In its the Ministry of Culture cited “obscene” performances in the eastern Chinese province of Jiangsu, as well as in Handan, and pledged to crack down on such lascivious last rites.

“In the Handan incident earlier this year, the ministry said, six performers had arrived to offer an erotic dance at the funeral of an elderly resident. Investigators were dispatched and the performance was found to have violated public security regulations, with the person responsible for the performing troupe in question detained administratively for 15 days and fined 70,000 yuan (about $11,300), the statement said. The government condemned such performances for corrupting the social atmosphere.

“The government has been trying to fight the country’s funereal stripper scourge for some time now. In 2006, the state-run broadcaster China Central Television’s leading investigative news show Jiaodian Fangtan aired an exposé on the practice of scantily clad women making appearances at memorial services in Donghai in eastern China’s Jiangsu province. CCTV found about a dozen funeral performance troupes offering such services in every village in the county, putting on as many as 20 shows a month at a rate of 2,000 yuan ($322) a pop. “This has severely polluted the local cultural life,” CCTV intoned at the time, marveling at the sight of one women gyrating out of her clothes mere steps from a photo of the deceased. “These troupes only care about money. As for whether it’s legal, or proper, or what effect it has on local customs, they don’t think much about it.”

According to CNN: China's Ministry of Culture said it had investigated two separate incidents, one in Handan City, Hebei Province, and the other in Suqian City, Jiangsu Province. Both involved multiple-participant "burlesque" and "striptease" shows as mourners looked on. The Ministry's report said that stripteases undermined "the cultural value of the entertainment business," and asserted that "such acts were uncivilized." Exotic dancing and other forms of pornography are illegal in China. The dancers in the two cases were held in "administrative detention" following the two investigations, the report added.

Corpse Fishers in China

bodies in the Yellow River

Kent Ewing wrote in the Asia Times, “Of all those around the world whose trades and professions are misunderstood and unfairly maligned, surely China's corpse fishers rank near the top. Since ancient times, these villagers have taken on the macabre task of salvaging human cadavers - victims of drowning, suicide and murder - from China's rivers and returning them to their families. For this lurid public service, they were traditionally thanked and appreciated.” [Source: Kent Ewing, Asia Times, September, 24 2010 Kent Ewing is a Hong Kong-based teacher and writer. He can be reached at kewing@netvigator.com. Original story on Wei Jinpeng was found McClatchy-Tribune News Service]

Describing a man named Wei Jinpeng who kept of bloated corpses he found floating in the Yellow River tethered to the shoreline, Ewing wrote: “Wei had run a pear orchard until 2003, when he realized that fishing dead bodies out of the river could provide a big boost to his income. Now Wei finds 80 to 100 bodies a year. His favorite hunting spot on the river is located about 30 kilometers from the city of Lanzhou, capital of northwestern Gansu province, because that is where a combination of a hydroelectric dam and a bend in the river causes bodies to surface. These bodies are young and old, male and female; some are bound; some are gagged; some, especially those of young women - probably migrant workers who had worked in Lanzhou - are never claimed and thus released back into the river.”

For bodies that are claimed, Wei has a price system that is sensitive to the income level of his customers. He charges the equivalent of US$75 to a farmer who claims a body, $300 to someone holding a job and $450 when a company is the payee. Other corpse snatchers are reported to charge $45 just to view a body (according to practice, bodies are kept face down in the river to preserve their features so that they will be recognizable to relatives) and nearly $900 for a claim.

This may have reminded readers of Zhang Yi's award-winning photograph, “Holding a Body for Ransom,” which quickly went viral on the Internet after it was taken last October. The photo appears to show a corpse fisher refusing to hand over the body of one of three university students who lost their lives while helping to rescue drowning children in the Yangtze River in Hubei province. The fisherman reportedly collected more than $5,000 - and heaps of media abuse - before finally turning over the bodies of the students.

The villain of this bigger piece is not Wei or any of his fellow body fishers, whose services are still very much required on the country's rivers. After all, if they don't pull the dead out of the national current, who will? Forget the local police, who want nothing to do with water-logged casualties of 21st-century China. Provincial authorities are even more averse to the stench of death. And the central government would only choose to act if a river became choked and toxic with human cadavers.

Although it is virtually unknown in the West, a recently released Chinese-made documentary presents a thoughtful portrait of those who make a living harvesting corpses along China's rivers. Director Zhou Yu's 52-minute film, called The Other Shore, shows how the ancient practice of body fishing has transformed from a public service into a private, profit-making business. Salvaging bodies out the river used to be a voluntary act of boatmen in olden times,” Zhou told the Global Times. “They returned the bodies as a favor. That time is over, and younger people have developed it into a business.”

As one member of the audience at a showing of the film in Beijing's 798 Art District was quoted as saying of corpse fishers: “I felt bad to see them fishing bodies like fishing boxes out of the water, but after all they are just simple people who try to make a living. If one day I need them to find someone from my family, I will be appreciative, even if I have to pay afterwards.”

Disputes and Fights Involving Dead Bodies in China

Yaqiu Wang wrote in China File: On the morning of March 16, 2016, “48-year-old Huang Shunfang went to her local hospital located in Fanghu Township in the central Chinese province of Henan. Her doctor diagnosed her with gastritis, gave her a dose of antacids through an IV, and sent her on her way. Huang died suddenly that afternoon. In the hours after her death, Huang’s family went to the hospital for an explanation and was told by the hospital leadership that “the hospital is where people die,” according to a witness’ account of the incident. Incensed, Huang’s family visited the local public security bureau and the health bureau, both to no avail. Four days later, on March 20, after rejecting the hospital’s offer of compensation of RMB 5,000 ($800), the family placed Huang’s corpse outside the gate of the hospital in protest. Soon, over a hundred policemen swooped in to take the body away, beating and detaining Huang’s relatives who tried to resist them. [Source: Yaqiu Wang, China File, May 6, 2015]

“A week earlier, at noon on March 9, during a forced residential demolition operation orchestrated by the township government in Jiangkou Township, Anhui province, 37-year-old Zhang Guimao died when his chicken coop collapsed on him. That afternoon, Zhang’s relatives, along with more than a hundred villagers, carried Zhang’s body into the township government office compound to demand an explanation. At midnight that day, all the streetlights suddenly went dark. Around two hundred riot police carrying shields appeared on the scene to take the body away to the crematorium, detaining at least six people in the process.

““Taishi kangyi,” or “carrying the corpse to protest,” is a practice with deep roots in Chinese history. Since late imperial times, people have employed it when judicial systems failed to provide a reliable channel of redress for injustice. These days, corpses are dragged into all manner of disputes involving medical malpractices, forced housing demolitions, vendor’s tussles with local patrols, and compensations for workplace accidents. When an accidental death occurs, citizens use the corpse to draw attention and invite sympathy from the wider public, all in an effort to put pressure on the authorities and to render a just outcome. This “highlights the distrust people feel about autopsies or investigations conducted by government organs and China’s justice system,” says Teng Biao, a civil-rights lawyer and visiting scholar at Harvard Law School. “Especially with the rise of social media in the past ten years or so, families of the dead can post photos or videos online. The rapid spread of such information can turn up the heat on local governments.”

bodies in the Yellow River “It’s that heat that perhaps has driven Chinese law enforcement to ever-more coordinated and deliberate attempts to curb corpse-keeping. A common scene across China today pits families, friends, and local residents barricading a dead body in concentric circles against police, often numbering in the hundreds and armed with batons and shields. The police break through the crowds to reach the corpse and “snatch” it. Local governments, following standard operating procedures developed in recent years, apply this practice known as “qiangshi,” or “snatching the corpse,” when a case of accidental death occurs. “The authorities’ rapid and forceful response focusing on the dead body demonstrates a model of preemptive intervention and suppression,” says Wu Qiang, a professor of political science at Tsinghua University.

“The most dramatic qiangshi clash in recent years followed the death of 24-year-old Tu Yuangao in Shishou, Hubei province. On June 17, 2009, Tu was found dead outside the hotel where he was working as a chef. Police quickly declared he had committed suicide, but the circumstances surrounding the death led Tu’s family to believe he was murdered. His relatives moved Tu’s body into the hotel lounge. Over the next three days, tens of thousands of local residents joined with Tu’s family to guard the body. Video clips posted online show protestors beating back waves of armed police whose numbers swelled into the thousands. Protesters also vandalized and toppled fire trucks and police vehicles. Tu’s family members, armed with two buckets of gasoline and more than a dozen gas tanks, vowed to protect Tu’s body to the death. Eventually, the hotel was set on fire and Tu’s family was forced to flee. After about 80 hours of fierce fighting, the government finally persuaded the family to move Tu’s body to a funeral parlor. On June 21, medical experts performed an autopsy on Tu, concluding the cause of death was “a fall from a height.” Four days later, Tu’s body was cremated.

Reasons for the Disputes and Fights Involving Dead Bodies

Yaqiu Wang wrote in China File: “According to a professor who has worked with the Chinese government on “internal security maintenance” but who asked not to be named because he was not authorized to speak publicly on this issue, Chinese authorities believe that corpses themselves can cause unrest. “After the Shishou incident in 2009, the Central Politics and Law Commission [the Chinese Communist Party organ that oversees the internal security forces and the court system] had a training video made for its police forces. In the video, it was said that the reason that the Shishou incident had escalated was due to the corpse, ‘the source of excitement,’ not having been removed in a timely manner. Since then, in all mass incidents [the official term for protests, riots, and other forms of social disorder in China] that involve death, removing the corpse became the number one priority.” [Source: Yaqiu Wang, China File, May 6, 2015]

“Several local government reports have also emerged online discussing the importance of quickly taking possession of corpses in these types of cases. A government official in Guang’an, Sichuan province writes, “The corpse is the most sensitive… People who have ulterior motives use the dead body to pressure the government… Onlookers, out of curiosity and sympathy, encircle the corpse forming a large crowd. If the corpse is not removed in time, a mass incident can break out at any time… [We must] ensure the corpse be moved to the funeral parlor without any conditions.” A report written by traffic police officers in Yongzhou, Hunan province, similarly notes that, “Empirical evidence shows the majority of traffic-accident-induced mass incidents are due to the corpse’s not being removed from the scene… After confirming the deaths, traffic police departments…should move the corpse to a funeral parlor as soon as possible.”

“But why is the dead body a “source of excitement”? One reason may have to do with tradition. In China, when someone dies of unnatural causes, his or her corpse is often tied to the idea of “yuan,” or “being wronged.” In the opening of the Song dynasty classic The Washing Away of Wrongs, published in 1247 and considered the world’s earliest documentation of forensic science, author and coroner Song Ci explains that the whole point of an accurate autopsy of an unnatural death is to “xiyuan zewu,” or “wash away wrongs and oblige others.” Today, popular TV dramas in China such as Witness to a Prosecution, which tells the story of Song Ci; Amazing Detective Di Renjie; or Young Justice Baopopularize these ideas. A typical narrative is as follows: A dead body is found. After a meticulous investigation, the protagonist solves the case. The story ends when yuan is “washed clean,” wrongs have been righted, and justice has been served.

“As sociologist and professor at Shanghai University of Political Science and Law Zhou Songqing writes, “In a mass incident, the corpse of a death in which the cause is unclear becomes a symbol. In its simple and even crude way, it is the embodiment of injustice and persecution. It arouses sympathy among the people surrounding [it].”

“The practice of using corpses to protest and seek retribution can be traced as far back as the Ming and Qing dynasties, when official parlance referred to it as “tulai,” or “conspiring to entrap.” Ming and Qing dynasty histories refer to how corpses were used to threaten or incriminate innocent people for financial or other gains. Both the Ming and Qing dynasties had specific laws punishing such conduct. The Qing Code, or daqing liuli, stipulates that those using the corpses of parents or grandparents for extortion should be sentenced to be flogged 100 times and serve three years in prison. Official narratives undoubtedly undermine the cases of those who had no choice but to employ the corpse as a way to have their grievances heard and addressed. Nevertheless, it attests to the prevalence and even effectiveness of such a practice. As historian Melissa Macauley nicely summarizes in her book Social Power and Legal Culture: Litigation Masters in Late Imperial China, the dead body is “one legal tool of empowerment.”

“In modern times, while the availability of information about disputes has increased and resulted in the more accurate recounting of death cases, an old practice continues to add weight in strengthening one’s case. In a well-known incident from Minquan county, Henan province in 1988, the local township government detained and beat peasant Cai Fawang who refused to hand over tax grain. Cai committed suicide by hanging himself in front of the police station. Cai’s wife and son first went to the township government office and put the dead body in the township Party Secretary’s office living quarters for 13 days. After the corpse began to decay and smell, they then placed the corpse in a coffin and parked the coffin in the yard of the government office building for nine months. A journalist who visited the village at that time wrote, “The township government was basically in exile. [They] tore a hole in the wall [of their office] to come and go by.” The powerful presence of the corpse, a constant reminder of injustice and suffering, clearly had an effect on the local government employees.

“Times have changed. It is difficult to imagine in today’s China that police would allow a dead body to remain out in the open for months, even letting it “take over” a local government office. As China’s economy continues to grow, social tensions have also mounted, with the number of mass incidents soaring in recent years. The Chinese government has responded with measures of its own, committing more money to internal stability maintenance than on the military in 2012 and 2013 (the 2014 public security budget was not publicized). Stymying these demonstrations to prevent escalation to major social unrest is now paramount.

“Yet ironically, the Chinese government’s “obsession with social stability” fuels instability because discontented citizens, aware that local authorities want to avoid all instances of social unrest, are effectively incentivized to employ more disruptive measures to “game the system,” says Carl Minzner, professor of law at Fordham Law School. “By threatening to create scenes of social unrest, like using dead bodies to protest, some people try to wring concessions from the authorities. Often, these are calculated decisions. And sometimes they produce results—such as higher monetary compensation—regardless of the underlying legal merit of the grievance.” The local authorities, Minzner adds, “simply are desperate to get protestors off the streets.”

Image Sources: Wiki Commons; Bucklin archives bodies, McClatchy-Tribune News Service

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2021