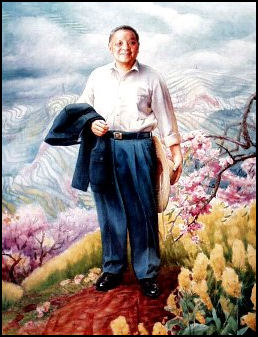

CHINA UNDER DENG XIAOPING

In his book "Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China", Ezra F. Vogel wrote that under Deng China transformed from a country with an annual trade of barely $10 billion to one whose trade expanded 100-fold. During his early years, Deng pleaded with the United States to take a few hundred Chinese students. Since then, 1.4 million have gone to study overseas. More than any other world leader, Deng embraced globalization, allowing his country to benefit from it more than any other nation. He also set the basis for a world-shaking demographic transition — by 2015, more than half of China's population will live in cities — that will dwarf all the massive population shifts due to wars and uprisings in China's past. [Source: John Pomfret, Washington Post, September 9, 2011]

In his book "Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China", Ezra F. Vogel wrote that under Deng China transformed from a country with an annual trade of barely $10 billion to one whose trade expanded 100-fold. During his early years, Deng pleaded with the United States to take a few hundred Chinese students. Since then, 1.4 million have gone to study overseas. More than any other world leader, Deng embraced globalization, allowing his country to benefit from it more than any other nation. He also set the basis for a world-shaking demographic transition — by 2015, more than half of China's population will live in cities — that will dwarf all the massive population shifts due to wars and uprisings in China's past. [Source: John Pomfret, Washington Post, September 9, 2011]

Harvard's Ezra Vogel wrote: “Did any other leader in the 20th century do more to improve the lives of so many” Did any other 20th-century leader have such a large and lasting influence on world history?” Vogel clearly believes that Deng - known in the West mostly for engineering the slaughter of protesters in the streets near Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989 — has been wronged by history.

Not everyone sees the Deng Xiaoping years in such a positive light. According to the New York Times: “While Deng put an end to the "iron rice bowl" – lifetime jobs for all – he ruled with an iron fist. The military suppression of the 1989 Tiananmen Square pro-democracy protests – believed to have taken place on his final orders – killed hundreds, perhaps thousands, and put a blot on the economic progress Deng had achieved. “

The population of China exceeded one billion in 1982 when Deng was at the helm. After that the pace of reforms picked up. "I remember the week things changed," a woman from Canton told Theroux, "There was a speech by Deng. Everyone responded to it. the Chinese are experts at interpreting jargon, and they knew he was saying something significant. It was one particular week in 1984, and after that everything was different." [Source: "Riding the Iron Rooster" by Paul Theroux]

Good Websites and Sources on Deng Xiaoping: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; CNN Profile cnn.com ; New York Times Obituary; China Daily Profile chinadaily.com. ; Wikipedia article on Economic Reforms in China Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on Special Economic Zones Wikipedia ;

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: AFTER MAO factsanddetails.com; AFTER MAO: THE RISE OF DENG XIAOPING factsanddetails.com; DENG XIAOPING'S LIFE factsanddetails.com; POLITICAL REFORM AND SOCIALIST DEMOCRACY UNDER DENG XIAOPING factsanddetails.com; FOREIGN POLICY UNDER DENG XIAOPING factsanddetails.com; DENG XIAOPING'S EARLY ECONOMIC REFORMS factsanddetails.com; DENG XIAOPING STEPS UP HIS ECONOMIC REFORMS: SEZS AND HIS SOUTHERN TOUR factsanddetails.com; ECONOMIC HISTORY AFTER DENG XIAOPING Factsanddetails.com/China TIANANMEN SQUARE DEMONSTRATIONS, 1989 factsanddetails.com; TIANANMEN SQUARE MASSACRE: VICTIMS, SOLDIERS AND EYEWITNESS ACCOUNTS factsanddetails.com; DECISIONS BEHIND THE TIANANMEN SQUARE MASSACRE factsanddetails.com;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Deng Xiaoping "Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China" by Ezra F. Vogel (Belknap/Harvard University, 2011) Amazon.com; “Deng Xiaoping: A Revolutionary Life” by Alexander V. Pantsov and Steven I. Levine Amazon.com; "Deng Xiaoping: My Father" by Deng Maomao (1995, Basic Books) Amazon.com; “Deng Xiaoping's Long War: The Military Conflict between China and Vietnam, 1979-1991" by Xiaoming Zhang Amazon.com; “The Deng Xiaoping Era: An Inquiry into the Fate of Chinese Socialism, 1978-1994" by Maurice Meisner Amazon.com; "Burying Mao: Chinese Politics in the Age of Deng Xiaoping" by Richard Baum (1996, Princeton University Press) Amazon.com; "Deng Xiaoping and the Chinese Revolution: A Political Biography" by David S.G. Goodman (1994, Routledge) Amazon.com; "Deng Xiaoping: Chronicle of an Empire" by Ruan Ming (1994, Westview Press) Amazon.com; "Deng Xiaoping and the Making of Modern China" by Richard Evans 1993 Amazon.com; "Deng Xiaoping: Portrait of a Chinese Statesman" edited by David Shambaugh (1995, Clarendon Paperbacks) Amazon.com; "The New Emperors: Mao and Deng — a Dual Biography" by Harrison E. Salisbury (1992, HarperCollins) Amazon.com After Mao “China After Mao: The Rise of a Superpower” by Frank Dikötter, Daniel York Loh, et al. Amazon.com; “Mao's China and After: A History of the People's Republic” by Maurice Meisner Amazon.com; “The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao” by Ian Johnson Amazon.com; The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 15: The People's Republic, Part 2: Revolutions within the Chinese Revolution, 1966-1982" by Roderick MacFarquhar, John K. Fairbank Amazon.com; "The Penguin History of Modern China" by Jonathan Fenby Amazon.com; “The Search for Modern China” by Jonathan D. Spence Amazon.com

China Opening Up — Sort of — Under Deng

According to “Countries of the World and Their Leaders”: “After 1979, the Chinese leadership moved toward more pragmatic positions in almost all fields. The party encouraged artists, writers, and journalists to adopt more critical approaches, although open attacks on party authority were not permitted. In late 1980, Mao's Cultural Revolution was officially proclaimed a catastrophe. Hua Guofeng, a protege of Mao, was replaced as premier in 1980 by reformist Sichuan party chief Zhao Ziyang and as party General Secretary in 1981 by the even more reformist Communist Youth League chairman Hu Yaobang. Reform policies brought great improvements in the standard of living, especially for urban workers and for farmers who took advantage of opportunities to diversify crops and establish village industries. Literature and the arts blossomed, and Chinese intellectuals established extensive links with scholars in other countries. [Source: Countries of the World and Their Leaders Yearbook 2009, Gale, 2008]

“At the same time, however, political dissent as well as social problems such as inflation, urban migration, and prostitution emerged. Although students and intellectuals urged greater reforms, some party elders increasingly questioned the pace and the ultimate goals of the reform program. In December 1986, student demonstrators, taking advantage of the loosening political atmosphere, staged protests against the slow pace of reform, confirming party elders’ fear that the current reform program was leading to social instability. Hu Yaobang, a protege of Deng and a leading advocate of reform, was blamed for the protests and forced to resign as CCP General Secretary in January 1987. Premier Zhao Ziyang was made General Secretary and Li Peng, former Vice Premier and Minister of Electric Power and Water Conservancy, was made Premier.

According to “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations”: “Until 1989, economic reforms were accompanied by relatively greater openness in intellectual spheres. A series of social and political movements spanning the decade from 1979 to 1989 were critical of the reforms and reacted to their effects. In the Democracy Wall movement in Beijing in the winter of 1978–79, figures like Wei Jingsheng (imprisoned from 1979 to 1994 and subsequently reimprisoned) called for democracy as a necessary "fifth modernization." A student demonstration in Beijing in the fall of 1985 was followed in the winter of 1986–87 with a larger student movement with demonstrations of up to 50,000 in Shanghai, Beijing, and Nanjing, in support of greater democracy and freedom. In June 1987, blamed for allowing the demonstrations, Hu Yaobang was dismissed as party General Secretary, and several important intellectuals, including the astrophysicist Fang Lizhi and the journalist Liu Binyan, were expelled from the party. At the 15th Party congress of November 1987, many hardline radicals failed to retain their positions, but Zhao Ziyang, who was confirmed as General Secretary to replace Hu, had to give up his position as Premier to Li Peng. By the end of 1988, economic problems, including inflation of up to 35% in major cities, led to major disagreements within the government, resulting in a slowdown of reforms. In December 1988, student disaffection and nationalism were expressed in a demonstration against African students in Nanjing. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Societal Changes During the Deng Era

Yu Hua wrote in The Guardian: “After Mao’s death, the economic reforms under Deng Xiaoping brought dramatic changes to China, changes that permeated all levels of Chinese society. In a matter of 30 years, we went from one extreme to another, from an era where human nature was suppressed to an era where human impulses could run riot, from an era when politics was paramount to an era when only money counts. [Source: Yu Hua, The Guardian, September 6, 2018. Yu Hua is a famous writer in China, considered a candidate for the Nobel Prize. He is the author of “Chronicle of a Blood Merchant”, “To Live” and “Brothers.”]

“Before, limited by social constraints, people could feel a modicum of freedom only within the family; with the loss of those constraints, that modest freedom which was once so prized now counts for little. Extramarital affairs have become more and more widespread and are no longer a cause for shame. It is commonplace for successful men to keep a mistress, or sometimes multiple mistresses — which people often jokingly compare to a teapot needing at least four or five cups to make a full tea set. In one case I know of, a wealthy businessman bought all 10 flats in the wing of an apartment complex. He installed his legally recognised wife in one flat, and his nine legally unrecognised mistresses in the other flats, one above the other, so that he could select at his pleasure and convenience on which floor of the building he would spend the night.

Myth Of the Third Plenum Meeting in 1978 That Began the Deng Economic Reforms

The Third Plenum in late 1978 is portrayed by the Chinese government as a historic meeting in which Deng began an era of market “reform and opening up.” Chris Buckley of the New York Times wrote: “But anyone looking for inspiration and instruction from Mr. Deng should beware: the conventional account of the 1978 meeting is a compound of selective memories, and a deceptive guide to how China’s steps to economic transformation really happened. “To put a halo on this meeting as a conference of reform and opening up is to concoct a myth,” Bao Tong, a former aide to ousted party secretary Zhao Ziyang, a central figure in the tumult of the 1980s, said in an interview with a Chinese researcher published in 2008. [Source: Chris Buckley, Sinosphere Blog, New York Times, November 9, 2013 ]

“The party’s widely repeated version of history depicts Mr. Deng as seizing control at the Third Plenum, or meeting, of the 11th Central Committee in late 1978. Inspired by Mr. Deng, the accounts suggest, the officials started China on market reforms, jettisoned the ideological debris of Mao Zedong’s era, and sidelined the old-guard party secretary, Hua Guofeng, who had defended Mao, resisted economic change, and stood in the way of rehabilitating officials purged by Mao. Since that time, Third Plenums of successive Central Committees have held a special place in China’s political calendar. They come every five years or so, and are when leaders lay down their priorities. The first such plenum in a leader’s tenure is especially important.

“But scholars who have studied that time using interviews, documents and memoirs offer an account of change that is more halting and less clear-cut. Mr. Deng emerges less a masterly visionary and more a canny politician, reacting to events and shifting his views step by step. “The official view of the Third Plenum, too often echoed in foreign studies, exaggerates the meeting,” said Frederick Teiwes, an emeritus professor of government at the University of Sydney, and Warren Sun, a historian at Monash University in Australia, in emailed remarks they prepared together. They are writing a book about that era.

“It ignores Hua’s achievements in moving the country away from Maoist orthodoxies and refocusing on the economy, underplays initial reform efforts before the Plenum, and oversimplifies a complex process that saw Deng emerge as paramount leader over the next two year,” the professors wrote. The word “market” did not appear in the official communiqué from the 1978 meeting; the word “reform” appeared twice. Only some six years later did the slogan “reform and opening up” become widely used, Professors Teiwes and Sun said.

“The shift occurred incrementally,” Professor Han said. “It wasn’t as if suddenly at the Third Plenum he was seized by inspiration to reform,” he said of Mr. Deng. “To date market economic reform thinking to that meeting is too early.” In fact, a document provisionally endorsed by the 1978 meeting explicitly opposed the “household responsibility system,” which became the watershed change that freed farmers from the grip of communes. That change allocated land to farmers and allowed them to contract production, so they could keep any surplus to eat or to sell. Mr. Deng and other leaders took years to come around to clearly supporting the policy; effectively ending the communes, an emblem of Mao’s socialism, did not come easily. Decisive momentum for the household policy came only in 1981, Professors Teiwes and Sun said.

Mao and Deng Xiaoping in the early Communist years

Drama at the Third Plenum Meeting in 1978

Chris Buckley of the New York Times wrote: “The drama in 1978 was played out at a work conference that preceded the formal Central Committee meeting; the two gatherings together are usually called the Third Plenum of that year. The assembled officials were supposed to discuss economic policy, but some began to urge leaders to confront the aftermath of Mao’s era and politically rehabilitate officials who were purged by him. [Source: Chris Buckley, Sinosphere Blog, New York Times, November 9, 2013 ]

“Neither Mr. Deng nor Mr. Hua instigated this shift. They had agreed beforehand that the meeting should focus on improving the economy, and Mr. Deng was abroad when the demands for rehabilitation burst out in the meeting sessions. “In reality, the meeting slipped out of control,” Mr. Bao, the former party aide, said in his 2008 interview. “Both Hua Guofeng and Deng Xiaoping were taken by surprise.”

“After he returned from abroad, Mr. Deng supported rehabilitating fallen cadres, but set limits and did not want to damage Mao’s standing, said Han Gang, a historian at East China Normal University in Shanghai who is writing a study of that period. “He wanted to focus on the future, and didn’t want to dwell on the details of the past,” Mr. Han said.

“The 1978 meeting endorsed adjustments in state planning to rejuvenate the economy, but changes were already underway. Mr. Hua has been depicted in earlier official accounts as a hapless defender of Maoist orthodoxy. But he recognized the need for change, although he faced damaging criticism for adjusting too slowly to shifting ideological winds, said Professors Teiwes and Sun. On the other hand, Mr. Deng gradually embraced the idea of market-driven economic growth, rather than adjustments within a state plan, Professor Han said. Before the Third Plenum, Mr. Deng and Mr. Hua shared similar views on the need to speed up economic growth and import more technology.

“The 1978 meeting marked Mr. Deng’s growing pre-eminence in the leadership, although he never formally took the formal title of party chief. Mr. Hua was effectively removed from office in late 1980, when impatience and dissatisfaction with him came to a head. The lessons from the 1978 meeting and Mr. Deng’s “groping” journey towards embracing market-driven reforms should discourage heady expectations. “Many people have a mindset of expectations that they put on a high-level decision-making meeting or a document,” he said. “But in reality in China making a sudden major change is very difficult. It takes time.”

Deng, Mao and Hua Guofeng at a Politburo meeting in 1960

Deng and Mao Communism

Mao was the great unifier of China. Deng was the man brought order to the world's most populous nation. This process of unification and order was a pattern that was repeated many times in Chinese history. William Wan wrote in the Washington Post, “When the chaos of the Cultural Revolution abated and Deng rose to power as the next leader, he criticized the cult of personality and said it was not only unhealthy, but also dangerous to build a country’s fate on the reputation of one man. In 1980, the party’s Central Committee issued directives for “less propaganda on individuals.” Party leaders have since continued to feature in propaganda and party-controlled newspapers but with less frequency and intensity. [Source: William Wan, Washington Post, July 25, 2014]

Deng tried by to abolish the Mao personality cult by declaring that Mao's influence on Chinese history was "70 percent positive and 30 percent negative." Deng added, "It is true that he made gross mistakes during the Cultural Revolution, but, if we judge his activities as a whole, his contributions to the Chinese Revolution far outweigh his mistakes."

Shortly after becoming the paramount leader of China, Deng called for the Chinese to "emancipate their minds." Thousands of people who had been persecuted during the Cultural Revolution were rehabilitated while Maoists were quietly removed from key positions of power. At the 1981 Party Congress, Deng labeled portraits as "feudal" and launched a "non-portrait-policy." In regard to his own mistakes, he said that a "large number of people" killed during the Anti-Rightist Campaign were "people who were made targets" and "actually good people."

Deng the General Manager

In a review of "Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China" by Ezra Vogel, John Pomfret of the Washington Post wrote, “When Deng finally returned to power for good in 1977, he avoided any direct criticism of the man who united China under the red flag of communism. Here again, Vogel provides great insight into how Deng succeeded in dismantling Maoism, liberating China's economy from the shackles of its ridiculous ideology and maintaining the man as a hero to the Chinese people. Deng did this, Vogel argues, because he believed that if he openly criticized Mao, it would threaten Communist Party rule. Deng thought that the party's aura of legitimacy must be preserved at all costs because only the party could save China. Deng's formula for success, as Vogel puts it, was simple: "Don't argue; try it. If it works, let it spread." [Source: John Pomfret, Washington Post, September 9, 2011]

Vogel calls Deng "the general manager" of China's latest revolution. As he pushed and pulled his country into the modern world, he was careful not to get out in front of the changes. He used younger officials such as Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang for that. (He ended up sacrificing both.) In fact, as Vogel reports, Deng wasn't even at the forefront of some of the most important political and economic moves - such as the 1976 arrest of the Gang of Four, including Mao's widow, Jiang Qing, and the decision to launch market-oriented special economic zones in the south that became hothouses for capitalist-style experimentation.

Vogel also provides enlightening details of Deng's efforts to use ties with the United States and Japan to China's advantage. While Mao opened China to the West as a way to counter the Soviet Union, Deng realized that American and Japanese technology, investment and knowledge would be keys to his country's advance. They were. Indeed, no nation has been more important to China's modernization than the United States - a fact that no Chinese official has ever acknowledged.

Vogel also has a skewed view of the events that forced Deng to reform China's economy,” Pomfret. According to him, Deng and his lieutenants, such as Wan Li, engineered the reforms. In reality, it seems that the Chinese people demanded them by, among other things, dismantling the commune system, and Deng and others were smart enough to get out of the way. Indeed, the Chinese people get short shrift in this book about China.

Deng’s Indirect Leadership Style

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books: Deng was a strong leader but in the 1980s “he chose to rule indirectly, through intermediaries like Zhao. This allowed him to discard lieutenants when things went wrong but ultimately hurt the party because it made a mockery of its own processes—Hu and Zhao had done nothing wrong and were not deposed according to any sort of party rules, but simply because Deng faced problems. It was also part of the reason for the Tiananmen protests, which began shortly after Hu’s death in April 1989. Many people mourned him precisely because they felt he had been poorly treated by Deng two years earlier. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, June 27, 2019; Review of “The Last Secret: The Final Documents from the June Fourth Crackdown”, published in Hong Kong by New Century Press in 2019 .]

“Senior leaders at the June 1989 meeting understood the problem. The eighty-one-year-old military and political leader Bo Yibo warned that the party would need to get behind one strong leader—a “core,” or hexin in Chinese—who commanded respect and could take firm control of the government. “In my view, history will not allow us to go through [a leadership purge] again,” Bo said.

“Deng also realized that the system he had created was faulty. He quickly handed over power to Jiang Zemin and got rid of the informal body of elders who had second-guessed Zhao for much of the 1980s. But until his death in 1997, Deng still hovered in the background. Jiang’s successor from 2002 to 2012, Hu Jintao, was likewise relatively weak. Jiang and Hu each served two terms, which was prematurely declared to be proof that the regime had institutionalized power transfers. In hindsight, this seems more like an interregnum that occurred because the party lacked a “core”—only Xi was able to assume this mantle after he took power in 2012. Not surprisingly, two of Xi’s signature policies have been to conduct a purge of top officials (in the guise of an anticorruption campaign) and to abolish term limits.

Deng Sayings and Slogans

Deng as a young Communist in the 1920s Deng's most famous saying—"It doesn't matter if the cat is black or white; if it catches mice, it's a good cat"—was a reference to his lack of interest in Communist ideology. He originally made the statement in the 1950s and later it was embraced as a kind of justification for his economic reforms.

Deng's second most famous saying — "To get rich is glorious" — expressed his break from Maoist philosophy and his aim to make China a "modern, powerful socialist country" by creating a "socialist market economy."

In an apparent allusion to freedom and democracy, Deng said, “Open the windows, breath the fresh air and at the same time fight the flies and insects."

Deng came up with his share of number slogans. He encouraged the Chinese to abide by the "Five Talks" (politeness, civil behavior, morality, attention to social relation and practice of good hygiene) and practice the "Four Beauties" (beautiful language, beautiful behavior, beautiful heart and beautiful environment).

Four Modernizations of Den Xiaoping

In 1979, Deng introduced the "Four Modernizations" to strengthen the sectors of 1) agriculture, 2) industry, 3) technology and 4) defense. Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “ Class struggle was no longer the central focus as it had been under Mao. The change in political climate was reflected in the propaganda posters of the 70s and 80s, which now promoted the creation of a society of civilized and productive citizens all working toward the welfare of the country and contributing to the modernization effort. Although there were still periodic campaigns against "bourgeois liberalization" or "spiritual pollution," overall the government relaxed its hold over cultural affairs. An important aspect of modernization was education. Educational institutions had been dismantled during the Cultural Revolution, and now it was necessary to rebuild them. Propaganda posters that encouraged study were frequently targeted at urban youth. “Another major change in the subject matter of propaganda from the 70s and 80s was the return of the intellectuals, a group that had frequently been accused of being "bourgeois" under Mao. Workers, peasants, and soldiers, while still portrayed, were no longer the only role models. Intellectuals had been elevated to the status of "mental workers" and were now shown as responsible and productive members of society. Although the government loosened its control over the people, it could still exert considerable coercive force when deemed necessary. Although Mao did not believe that it was necessary to control the Chinese population, since his death the government has worked hard to promote the one-child policy. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

The culmination of Deng Xiaoping's re-ascent to power and the start in earnest of political, economic, social, and cultural reforms were achieved at the Third Plenum of the Eleventh National Party Congress Central Committee in December 1978. The Third Plenum is considered a major turning point in modern Chinese political history. "Left" mistakes committed before and during the Cultural Revolution were "corrected," and the "two whatevers" policy ("support whatever policy decisions Chairman Mao made and follow whatever instructions Chairman Mao gave") was repudiated. The classic party line calling for protracted class struggle was officially exchanged for one promoting the Four Modernizations. In the future, the attainment of economic goals would be the measure of the success or failure of policies and individual leadership; in other words, economics, not politics, was in command. To effect such a broad policy redirection, Deng placed key allies on the Political Bureau (including Chen Yun as an additional vice chairman and Hu Yaobang as a member) while positioning Hu Yaobang as secretary general of the CCP and head of the party's Propaganda Department. Although assessments of the Cultural Revolution and Mao were deferred, a decision was announced on "historical questions left over from an earlier period." The 1976 Tiananmen Square incident, the 1959 removal of Peng Dehuai, and other now infamous political machinations were reversed in favor of the new leadership. New agricultural policies intended to loosen political restrictions on peasants and allow them to produce more on their own initiative were approved. [Source: The Library of Congress]

“At the plenum, party Vice Chairman Ye Jianying pointed out the achievements of the CCP while admitting that the leadership had made serious political errors affecting the people. Furthermore, Ye declared the Cultural Revolution "an appalling catastrophe" and "the most severe setback to [the] socialist cause since [1949]." Although Mao was not specifically blamed, there was no doubt about his share of responsibility. The plenum also marked official acceptance of a new ideological line that called for "seeking truth from facts" and of other elements of Deng Xiaoping's thinking. A further setback for Hua was the approval of the resignations of other leftists from leading party and state posts. In the months following the plenum, a party rectification campaign ensued, replete with a purge of party members whose political credentials were largely achieved as a result of the Cultural Revolution. The campaign went beyond the civilian ranks of the CCP, extending to party members in the PLA as well.

Famous Speeches by Deng Xiaoping

with Nixon and Carter

In the “Uphold the Four Basic Principles” speech of March 30, 1979, Deng laid forth what he called the “Four Basic Principles,” which continue to be a part of the Chinese Communist Party’s ideological foundation and serve as a justification for Party actions taken to control intellectual and political activity. Deng said: “The [Party] Center believes that in realizing the four modernizations in China we must uphold the four basic principles in thought and politics. They are the fundamental premise for realizing the four modernizations. They are [as follows]: 1) We must uphold the socialist road. 2) We must uphold the dictatorship of the proletariat. 3) We must uphold the leadership of the Communist Party. 4) We must uphold Marxist-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought. [Source:“Sources of Chinese Tradition: From 1600 Through the Twentieth Century”, compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary and Richard Lufrano, 2nd ed., vol. 2 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), 492-493 ]

“The Center believes that we must reemphasize upholding the four basic principles today because some people (albeit an extreme minority) have attempted to shake those basic principles. … Recently, a tendency has developed for some people to create trouble in some parts of the country. … Some others also deliberately exaggerate and create a sensation by raising such slogans as “Oppose starvation” and “Demand human rights.” Under these slogans they incite some people to demonstrate and scheme to get foreigners to propagandize their words and actions to the outside world. The so-called China Human Rights Organization has even tacked up big character posters requesting the American president “to show solicitude” toward human rights in China. Can we permit these kinds of public demands for foreigners to interfere in China’s domestic affairs? A so-called Thaw Society issued a proclamation openly opposing the dictatorship of the proletariat, saying that it divided people. Can we permit this kind of “freedom of speech,” which openly opposes constitutional principles?

In the "The Present Situation and the Tasks Before Us" of January 16, 1980, Deng laid forth his analysis of China’s situation and the most pressing tasks at hand: “First, it is essential to follow a firm and consistent political line. We now have such a line. In his speech at the meeting in celebration of the 30th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic, Comrade Ye Jianying formulated the general task — or, if you will, the general line — as follows: Unite the people of all our nationalities and bring all positive forces into play so that we can work with one heart and one mind, go all out, aim high and achieve greater, faster, better, and more economical results in building a modern, powerful socialist country. [Source: “Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping (1975-1982) (Beijing: Foreign Language Press, 1984), 224-258 ]

“The socialist system is one thing, and the specific way of building socialism another. This superiority [of the socialist system] should manifest itself in many ways, but first and foremost it must be revealed in the rate of economic growth and in economic efficiency. Without political stability and unity, it would be impossible for us to settle down to construction. This has been borne out by our experience in the more than twenty years since 1957. In addition to stability and unity, we must maintain liveliness … when liveliness clashes with stability and unity, we can never pursue the former at the expense of the latter. The experience of the Cultural Revolution has already proved that chaos leads only to retrogression not to progress.”

Life in the Early Deng Years

Shanghai in 1980

In an article about the 346-page Chinese-language book, “Straight Talks: Chinese Social Discourses from 1978-2012” by Liu Qingsong, Mei Jia wrote in the China Daily: “In 1978 there was a movement against flared trousers. Teachers would then catch the offenders and cut off the "extra" cloth in an effort to keep the young away from "bourgeois corruption", symbolized by such "weird" fashion. And till March that year, quotes by Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Vladimir Lenin, and Mao Zedong had to be printed in bold while published in newspapers. It was Deng Xiaoping who put a stop to the practice. [Source: Mei Jia, China Daily, February 24, 2016 ~~]

“The book also contains a story of how film director Zhang Yimou gained access to university after three years of farm work and seven years of factory labor, when entrance exams for universities were resumed. It also tells how perplexed then 19-year-old Zhang Huamei, from Wenzhou, Zhejiang province, was when she got the news that she would receive the country's first certificate to run a private business in December 1980. Zhang, the book says, was reluctant to take the piece of paper home, since she worried that she would be punished in the future for stepping into the realm of a market economy. But her father, the book adds, said to her, the country is determined to reform, so go ahead. ~~

“The book, an updated second edition of a 2009 release...by Contemporary China Publishing House. Beijing-based Liu Qingsong, 41, tells China Daily that he decided to compile the book in 2008 after realizing that his younger friends had very limited knowledge about the road China had taken, "because what they now see is so different from just decades ago, what they have now is so much better". Liu, born in Wanzhou in southwestern Chongqing, says he remembers a time when the neighbor's two daughters shared one pair of decent trousers, so when market day came, only one had the chance to go out and enjoy the fair. Liu would like readers to see how society has gradually opened up, and "how every individual has gone from not knowing to knowing and from having limited choices to being spoilt for choice". ~~

China in the 1980s

Scott Savitt, a journalist in China in the 1980s and 90s, told the LA Review of Books Blog: “I arrived in China in 1983 and it was really the honeymoon stage. The Communist Party has admitted that they fucked up under Mao, that they have to go in a different direction. Nobody knows what “gaige kaifang” [reform and opening up] really means. There’s still a Mao hangover. They’re breaking up the communes in the countryside, in the cities people start buying and selling vegetables in free markets. The Party’s propaganda had run out of steam completely, and so everybody knew that everything they’ve taught us is a lie.The 1980s felt like springtime — though of course it wasn’t. Mao’s henchman Deng Xiaoping was still in power, and politically active people were getting arrested all the time. But the difference between then and now really is like night and day. The equivalent would be pre-709 crackdown [the mass arrest of Chinese human rights lawyers from July 9, 2015]. You know it’s dangerous, but people are speaking out anyway. Whether it succeeds or not, being among a group of people who are living for a larger cause is really inspiring. That’s how the 1980s was. [Source: Matthew Robertson, LA Review of Books Blog, May 31, 2017, Interview with Scott Savitt]

Jiangsu in 1983

Mark Kitto wrote in Prospect Magazine, “When I arrived in Beijing...from London University’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), China was communist. Compared to the west, it was backward. There were few cars on the streets, thousands of bicycles, scant streetlights, and countless donkey carts that moved at the ideal speed for students to clamber on board for a ride back to our dormitories. My “responsible teacher” (a cross between a housemistress and a parole officer) was a fearsome former Red Guard nicknamed Dragon Hou. The basic necessities of daily life: food, drink, clothes and a bicycle, cost peanuts. We lived like kings — or we would have if there had been anything regal to spend our money on. But there wasn’t. One shop, the downtown Friendship Store, sold coffee in tins. [Source: Mark Kitto, Prospect Magazine, August 8, 2012]

"We had the time of our lives, as students do, but it isn’t the pranks and adventures I remember most fondly, not from my current viewpoint, the top of a mountain called Moganshan, 100 miles west of Shanghai, where I have lived for the past seven years. If I had to choose one word to describe China in the mid-1980s it would be optimistic. A free market of sorts was in its early stages. With it came the first inflation China had experienced in 35 years. People were actually excited by that. It was a sign of progress, and a promise of more to come. Underscoring the optimism was a sense of social obligation for which communism was at least in part responsible, generating either the fantasy that one really could be a selfless socialist, or unity in the face of the reality that there was no such thing.

"In 1949 Mao had declared from the top of Tiananmen gate in Beijing: “The Chinese people have stood up.” In the mid-1980s, at long last, they were learning to walk and talk. One night in January 1987 I watched them, chanting and singing as they marched along snow-covered streets from the university quarter towards Tiananmen Square. It was the first of many student demonstrations that would lead to the infamous “incident” in June 1989.

"One man was largely responsible for the optimism of those heady days: Deng Xiaoping, rightly known as the architect of modern China. Deng made China what it is today. He also ordered the tanks into Beijing in 1989, of course, and there left a legacy that will haunt the Chinese Communist Party to its dying day. That “incident,” as the Chinese call it — when they have to, which is seldom since the Party has done such a thorough job of deleting it from public memory — coincided with my final exams. My classmates and I wondered if we had spent four years of our lives learning a language for nothing.

"It did not take long for Deng to put his country back on the road he had chosen. He persuaded the world that it would be beneficial to forgive him for the Tiananmen “incident” and engage with China, rather than treating her like a pariah. He also came up with a plan to ensure nothing similar happened again, at least on his watch. The world obliged and the Chinese people took what he offered. Both have benefited financially."

Visiting China in 1984

Beijing in 1988

On visiting China in 1984, James Mann of the Los Angeles Times wrote,”We were taken to the place that would serve as our home for the next few days: the recently-completed Great Wall Hotel. For decades, visitors to Beijing had stayed in older hotels like the Beijing, Minzu and Qianmen. Now, the city had started to build a series of next-generation hotels: the Great Wall Hotel had followed on the Jianguo, to be followed next by the Jinglun (Beijing-Toronto). Our hotel seemed almost as if it were designed for the same purpose as the world-famous fortifications for which it was named: to help keep foreigners out of China. Its cavernous new restaurants tried to serve an array of Western dishes — club sandwiches, French fries, spaghetti Bolognese — none of which tasted quite right and all of which left one yearning for real food, whether Chinese or Western. [Source: James Mann, hkej.com, April 30, 2011 |=|]

“In fact, the strongest impression I had throughout the trip was of how different China seemed from what was being written about it. By the mid-1980s, American newspapers and magazines were full of stories about how China was changing: new hotels, discos, golf courses. The stories were not inaccurate, but once there, you saw how marginal and fragile the innovations still were, how they were surrounded and overwhelmed by a different China that didn’t appear as much in the American press coverage, a China that still remained untouched by westernization.” |=|

"Several months later, I flew off to Beijing again, this time with family and unpacked with them, first in the Jianguo and then in Jianguomenwai. Almost immediately after arrival, I was told there the Foreign Ministry was offering a trip for reporters to visit Qinghai, which until that time had been a province closed to the outside world. One Australian diplomatic delegation had been allowed into Qinghai a couple of years earlier, and had reported seeing huge labor-camp facilities. I signed on. This was, in the 1980s, one of the last of the large Foreign Ministry organized trips; China was opening up, allowing more latitude for reporters to travel on their own.” |=|

“En route, we stopped for a day in Lanzhou, where we were taken to a large chemical factory. The air was smoky and foul. When it came time for questions, one of my colleagues asked for data on occupational safety and pulmonary diseases. The answer came back in a phraseology I had never heard before, but which would soon be familiar: ‘since the Third Plenum of the Eleventh Central Committee?” |=|

Jiangsu in 1983

“Once in Qinghai, we were taken to a factory that made carpets in Xining, the capital city. On them, we noticed, were labels that said, “Made in Shanghai.” Later that day, leaving the city on a bus, we could see on the outskirts a large institution surrounded by high walls, with armed guards in a watchtower.” On the way home, as we were passing it again, a couple of photographers called out, ‘stop the bus, I’ m feeling sick.” Once outside, they began to shoot pictures. Suddenly, a local official supposedly from the Qinghai Waiban turned out to be a security official grabbing cameras. “This is not a labor camp,” Chinese officials told us. “It’s a hydroelectric factory.” |=|

“The following day, we were taken to the spacious, ornate Tibetan monastery at Taer Si, southwest of Xining. Chinese officials brought out a Living Buddha who had been released from prison a few years earlier. We asked him how long he had he been in jail’since the Cultural Revolution, we supposed” No, since 1958, since the time of the “crushing of the Tibetan rebellion,” he said. He had been accused of “counterrevolutionary crimes,” he said, and sent off to join the program of “laodong gaizao” (more commonly known as “laogai,” reform through labor). And where had he been imprisoned” “Up the road, at the place they call the hydroelectric factory,” he answered, knowing nothing of the incident the day before.” |=|

“In front of thirty people, a Qinghai provincial official whispered to the Foreign Ministry-assigned translator to say he had said that the institution in question was now a hydroelectric factory, not a labor camp. The Foreign Ministry translator refused. “He did not say that,” he retorted, summoning forth both the spirit of apolitical professionalism that often prevailed in the mid-1980s and also the disdain of a Shanghai-born, Beijing-living Foreign Ministry official for the uncouth crudity of the backwards provincials...After the isolation of the Reagan trip and the glitzy emptiness of the new Beijing hotels, I now felt that I had finally arrived in China itself, a place full of stories a reporter only rarely found out about and complexities an outsider struggled to understand.” |=|

Deng Xiaoping and Zhao Ziyang in 1984

”I met Deng Xiaoping. Sort of,” Mann wrote. “It wasn’t exactly a one-on-one. I was standing on a row of bleachers, along with many other properly-badged journos, in the room where Deng welcomed the Reagans, husband and wife. Deng wandered over to the bleachers to say hello. What was my first impression” To borrow the immortal words of Richard Nixon at the Great Wall (‘ It really is a great wall’ ), Deng really was very short. He also, it turned out, had an impish sense of humor: In front of the assembled reporters, he turned to Nancy Reagan and told her that her visit was too short. “I hope you’ ll come the next time and leave the president home,” he said. “You come just by yourself, independently — We won’t maltreat you.” Reagan had spent many decades and two careers handling that sort of patter. “It sounds like I’m the one being maltreated,” he replied genially. Was this a Sino-American summit, or Jack Benny and Bob Hope” No time to find out further: The reporters were ushered out before the conversation could turn more serious.” [Source: James Mann, hkej.com, April 30, 2011]

old Deng

"That brief first glimpse of Deng was also my last one. Over the following years, living in and covering China, I never saw Deng again. In Beijing, I would be able to see once in a while the color of Hu Yaobang’s [brown] socks, and the cut of Zhao Ziyang’s many [grey] suits. More often, though, reporters in that era saw only the more limited wardrobe of the loyal, repeat-the-line Foreign Ministry press spokesman, Li Zhaoxing (whose haberdashery would improve over the following decades as he rose through the ranks to become foreign minister).

“At the opening banquet, in which Zhao hosted Reagan, I was seated so far from the head table it would have taken a ten-minute bicycle ride to get there. The People’s Liberation Army played “My Old Kentucky Home” and “Home on the Range.” The Chinese dinner partner on my right looked sufficiently distinguished to run a ministry, but turned out to be a telex operator."

Image Sources: Wikicommons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2021