MAO'S LEADERSHIP

Under Mao decisions were often made on the basis of whims, biases and ignorance, often without careful study of their impact or considering the human and environmental costs. Features of the revolutionary era's mass politics included flamboyant and typically baseless scapegoating, slogan-based campaigns aimed not just at inciting the fury of the masses but at channeling it against ever-shifting ideologically designated “enemies,” and vicious and often unrelenting sectarian attacks."Mao's contradictory insistence on the absolute loyalty of his subordinates," wrote historian Marilyn B. Horne, "as well as their absolute honesty insured that only the subservient prevailed." Mao anointed and then purged several “Number Two” men and apparent successors.

Under Mao decisions were often made on the basis of whims, biases and ignorance, often without careful study of their impact or considering the human and environmental costs. Features of the revolutionary era's mass politics included flamboyant and typically baseless scapegoating, slogan-based campaigns aimed not just at inciting the fury of the masses but at channeling it against ever-shifting ideologically designated “enemies,” and vicious and often unrelenting sectarian attacks."Mao's contradictory insistence on the absolute loyalty of his subordinates," wrote historian Marilyn B. Horne, "as well as their absolute honesty insured that only the subservient prevailed." Mao anointed and then purged several “Number Two” men and apparent successors.

A primary goal of the People's Republic of China since its inception in 1949 has been to catch up and surpass the rest of the world in all aspects: culture, national defense, technology, sports. Frank Hawke, a resident of Beijing since the 1970s, told the New York Times that when Chinese “feel they’ve made a huge leap forward, there’s an incredible national pride. A psychological theme that runs throughout China” is that the “Chinese feel they have this great culture, second to none, and yet here they are, a third world developing country.”

The Mao Marxist revolution set to create New man, who prosper in a society where class distinctions had been eliminated and progress was defined by dialectal reasoning. The economic reformer Zhao Ziyang wrote that in Mao’s China “self-reliance” was “an absolute virtue” that became an ideological pursuit and was politicized.

Websites: Communist Party History Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Illustrated History of Communist Party china.org.cn ; Books and Posters Landsberger Communist China Posters ; People’s Republic of China: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; China Essay Series mtholyoke.edu ; Everyday Life in Maoist China.org everydaylifeinmaoistchina.org;

The Long March: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Paul Noll site paulnoll.com ; Chinese Government Account of Events chinadaily.com; Long March Remembered china.org.cn ; Long March map china.org.cn

Websites: Communist Party History Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Illustrated History of Communist Party china.org.cn ; Books and Posters Landsberger Communist China Posters ; People’s Republic of China: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; China Essay Series mtholyoke.edu ; Everyday Life in Maoist China.org everydaylifeinmaoistchina.org;

The Long March: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Paul Noll site paulnoll.com ; Chinese Government Account of Events chinadaily.com; Long March Remembered china.org.cn ; Long March map china.org.cn

Mao Zedong Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Mao Internet Library marx2mao.com ; Paul Noll Mao site paulnoll.com/China/Mao ; Mao Quotations art-bin.com; Marxist.org marxists.org ; New York Times topics.nytimes.com; Early 20th Century China : John Fairbank Memorial Chinese History Virtual Library cnd.org/fairbank offers links to sites related to modern Chinese history (Qing, Republic, PRC) and has good pictures;

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: REPRESSION UNDER MAO, THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION AND NIXON factsanddetails.com; REPUBLICAN CHINA, MAO AND THE EARLY COMMUNIST PERIOD factsanddetails.com; MAO'S PRIVATE LIFE AND SEXUAL ACTIVITY factsanddetails.com; JIANG QING, LIN BIAO, ZHOU ENLAI factsanddetails.com; COMMUNISTS TAKE OVER CHINA factsanddetails.com; FAMOUS ESSAYS BY MAO ZEDONG AND OTHER CHINESE COMMUNISTS AS THEY TAKE POWER factsanddetails.com; EARLY COMMUNIST CHINA UNDER MAO factsanddetails.com; CHINA, THE KOREAN WAR, POWS, SPIES AND THE C.I.A. factsanddetails.com; CHINESE TAKEOVER OF TIBET IN THE 1950s factsanddetails.com; COMMUNES, LAND REFORM AND COLLECTIVISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; DAILY LIFE IN MAOIST CHINA factsanddetails.com; BAREFOOT DOCTORS AND HEALTH CARE IN THE MAO ERA factsanddetails.com; DEATH AND REPRESSION UNDER MAO factsanddetails.com; HUNDRED FLOWERS CAMPAIGN AND THE ANTI-RIGHTIST MOVEMENT factsanddetails.com; GREAT LEAP FORWARD: MOBILIZING THE MASSES, BACKYARD FURNACES AND SUFFERING factsanddetails.com; GREAT FAMINE OF MAOIST-ERA CHINA: MASS STARVATION, GRAIN EXPORTS, MAYBE 45 MILLION DEAD factsanddetails.com; TOMBSTONE AND RESEARCH OF THE GREAT FAMINE factsanddetails.com; CHINESE REPRESSION IN TIBET IN THE LATE 1950s AND EARLY 1960s factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: "Mao; the Untold Story" by Jung Chang and Jon Halliday (Knopf. 2005) Amazon.com; “Mao Cult: Rhetoric and Ritual in China's Cultural Revolution” Illustrated Edition by Daniel Leese ( Amazon.com; “Mao Zedong” by Jonathan Spence, Alexander Adams, et al. Amazon.com; "The Private Life of Chairman Mao" by Dr. Li Zhisui (1994) Amazon.com; “Mao Zedong: A Political and Intellectual Portrait” by Maurice Meisner Amazon.com; "Mao's New World: Political Culture in the Early People's Republic" by Chang-tai Hung (Cornell University Press, 2011) Amazon.com; “Mao Zedong: The Complete Works Volume 1" (Before 1934) Amazon.com; “Mao Zedong: The Complete Works Volume 2" (1934-1938) Amazon.com; “Mao Zedong: The Complete Works Volume 3" (1938-1941) Amazon.com; “Mao Zedong: The Complete Works Volume 4" (1941-1945) Amazon.com; “Mao Zedong: The Complete Works Volume 5" ( 1944 and 1948) Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 14: The People's Republic, Part 1: The Emergence of Revolutionary China, 1949-1965" by Roderick MacFarquhar and John K. Fairbank Amazon.com

Mao and Chiang K Chek in 1946

Mao's Motivation

Dr. Homare Endo of the University of Tsukuba believes that Mao Zedong’s ideas are actually the ideas of an emperor, not Marxism-Leninism. He used Marxism-Leninism to become China's leader, she has argued, and returned China to the feudal state of the previous Chinese imperial era. She believes that Mao Zedong did not value the Chinese nation or Marxism-Leninism, becoming the emperor of China was the most important thing to him. She said: “In his philosophy, he is the blood of the emperor and wants to become a feudal emperor. For Mao Zedong, hundreds of thousands of ordinary people starved to death and collusion with the Japanese army was a trivial matter of course, and he could do everything he could to win.”

Based on Karl Marx's view that the "the proletariat cannot liberate itself without liberating the whole of humankind", Mao's internationalism holds that Chinese people must support anti-oppression movements worldwide. Mao used to organize massive demonstrations at Tiananmen Square and issued statements to show Chinese people's support for "revolutionary" movements across the world.

While most viewed war as a disaster, Mao saw it — or at least the threat of it — as an opportunity. He often used threats and provocations as way to gain concessions with both allies and enemies alike. He famously called the much richer and stronger United States a “paper tiger” and once said to Khrushchev that nuclear war was just “a big pile of people dying.” The Soviets worried that Mao was crazy and as a result tread carefully with him. It can be argued that North Korea uses the same tactics today. [Source: New York Times]

Kissinger on His Meeting With Mao

Appointments with Mao were never scheduled, Henry Kissinger wrote in Newsweek, "They simply came about as if events of nature. On each of my five meetings with Mao, the first hint would be a stirring among my Chinese interlocutors and the appearance of Assistant Foreign Minister Wang Hairong, reputed to be Mao's niece. For a few minutes, my clearly agitated Chinese counterparts would act as if nothing unusual was happening. Then, almost immediately, Zhou or Deng would put away his papers and say: "Chairman Mao is expecting you." [Source: "Years of Renewal by Henry Kissinger, 1998, Little, Brown and Co.]

"The all powerful ruler of the world's most populous nation wished to be perceived as a philosopher king who had no need to buttress any traditional symbol of majesty," Kissinger wrote. "Mao would rise from the center of a semicircle of easy chairs, a female attendant standing close to steady him (and, on my last visit, to hold him up)...He would fix upon his visitor a smile both penetrating and slightly mocking, as if to warn that there was no point trying to deceive this specialist in understanding and exploiting human weakness and duplicity."

"Mao conducted conversations in a Socratic style," Kissinger wrote. "He would generally begin with a question, quite often in a needling tone. With deceptive casualness, he would then offer a few pithy comments, ranging from the philosophical to the sarcastic and culminating in yet another question. The cumulative effect of his tangential observations was to convey a mood while avoiding any commitment.”

Mao and the Dalai Lama in 1954

Stalin’s Influences on Mao’s Policies

Pankaj Mishra wrote in The New Yorker, “The Soviet Union was the first among many "underdeveloped" countries in which national leaders with pseudo-scientific visions of socioeconomic engineering exposed their societies to immense suffering. In the early nineteen-twenties, the Bolsheviks, emerging from a destructive civil war and an invasion by Western countries, urgently wanted to industrialize their country, as the first step to Communism. In the absence of any foreign investment, industrialization depended on generating adequate capital from agricultural surpluses, and the Bolsheviks initially experimented, partly successfully, with free-market agriculture and private ownership. In 1929, however, Stalin decided to speed up the Soviet Union's tryst with industrial power, by forcing peasants into collective farms. Those who resisted — for instance, by slaughtering livestock or by refusing to plant or harvest grain — were ruthlessly crushed. The toll in human suffering was enormous — millions of peasants, many of them in Ukraine, were killed or starved to death. By the mid-thirties, the Stalinists had won. Collective farms became a permanent feature of Soviet life, and the Soviet Union became an industrialized country. Its seemingly limitless ability to produce the military hardware necessary to fight — and win — its ferocious war with Nazi Germany was a testament to its success. [Source: Pankaj Mishra, The New Yorker, December 10, 2012 ]

“Few people in China in the nineteen-twenties and thirties observed Stalin's brutal but efficacious engineering more closely than Mao Zedong, then a restless young convert to Communism. Like many Chinese picking their way through the ruins of the Qing Empire, Mao was convinced that China had to transform itself, as the Soviet Union had done, into a powerful nation-state in order to survive the hostility of the capitalist-imperialist West. In this project, the Soviet Union was the indispensable nation, first as fraternal pioneer and then as ideological foil. Pantsov and Levine's examination of Russian archives reveals that the Chinese Communist Party, from its inception, in 1921, was deeply dependent on Soviet money, expertise, and ideological guidance. It also shows, in absorbing detail, how Mao's catastrophic "concept of a special Chinese path of development," as Pantsov and Levine assert, "could arise only in the post-Stalin environment."

“In 1949, Mao achieved victory in the drawn-out civil war against the Nationalists, who were backed by the Americans and led by Chiang Kai-shek, and he began the "Stalinization" of China soon afterward. He used the Stalinist tool kit — coercion and propaganda — to build a strong state upheld by a single party, a loyal military, and intrusive micromanagement of the lives of the citizens. Henceforth, the Chinese were told where to live, work, and study, and how many children to have. The Soviets offered models for everything, from urban planning to labor camps and physical-fitness drills. And Soviet experts were on hand to supervise, as Mao instituted land reforms, abolished private property, silenced intellectual critics, segregated rural and urban populations, and launched Stalinist-style purges against counter-revolutionaries and rich peasants.

Mao and Stalin in 1949

“As in the Soviet Union, Chinese leaders had to raise capital through increased agricultural yields before they could start investing in extensive industrialization. However, unlike Stalin, Mao faced relatively little resistance to his program of collectivization. Furthermore, the first modernizing attempts of the People's Republic of China were strikingly successful. Industrial and agricultural production soared — the annual growth rate in the early nineteen-fifties was almost eighteen per cent. The Party acquired a popular base in the countryside among peasant beneficiaries of land reforms. (Affection for Mao among the rural population was one reason for the strange lack of public disaffection when the famine came.) The social climate improved, thanks to mass campaigns against prostitution, arranged marriages, and opium use. Expanding literacy and health care gave China an early and enduring lead over other post-colonial countries, including India.

“But China's "patriotic engineer" was not content, telling his personal physician, "When I say, 'Learn from the Soviet Union,' we don't have to learn how to shit and piss from the Soviet Union, too, do we?" Mao was intellectually insecure, having risen to power only after long and bitter struggles with better-educated, Soviet-backed Party leaders; he had always resented the unbalanced and yet unavoidable Chinese relationship with the Soviet Union. Stalin's death, in 1953, and Nikita Khrushchev's repudiation of Stalin, in 1956, helped Mao finally break free of his dependency. Socialism in China, as he saw it, was to be "more, better, faster" than even Stalin could imagine. Using the country's great advantage — cheap and abundant labor — China would make the Great Leap Forward, doubling, even tripling, agricultural and industrial production in a few years.

Book” "Mao: The Real Story," by Alexander V. Pantsov and Steven I. Levine (Simon & Schuster 2012), draws on Russian archives to show, more clearly than before, that this apparently unparalleled tale of cruel folly was not without precedent in the twentieth century — the age of ideological excess.

Khrushchev and Mao

Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev made several trips to China. Mike Dash wrote in Smithsonianmag.com: In the course of these visits, found himself playing cat-and-mouse with the chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, Mao Zedong–. It was a game, the Soviet leader was discomfited to find, in which Mao was the cat and he the mouse. [Source: Mike Dash, Smithsonianmag.com, May 4, 2012]

“His first, in 1954, had proved difficult; Khrushchev’s memoirs disparagingly describe the atmosphere as “typically oriental. Everybody was unbelievably courteous and ingratiating, but I saw through their hypocrisy…. I remember that when I came back I told my comrades, ‘Conflict with China is inevitable.’ ” Returning in the summer of 1958 after several stunning Soviet successes in the space race, including Sputnik and an orbit of the earth made by a capsule carrying a dog named Laika, the Soviet leader was amazed at the coolness of the senior Chinese officials who gathered to meet him at the airport. “No red carpet, no guards of honor, and no hugs,” interpreter Li Yueren recalled — and worse followed when the Soviets unpacked in their hotel. Remembering Stalin’s treatment of him all too clearly, Mao had given orders that Khrushchev be put up in an old establishment with no air conditioning, leaving the Russians gasping in the sweltering humidity of high summer in Beijing.

“When talks began the next morning, Mao flatly refused a Soviet proposal for joint defense initiatives, at one point leaping up to wave his finger in Khrushchev’s face. He chain-smoked, although Khrushchev hated smoking, and treated his Soviet counterpart (says Khrushchev biographer William Taubman) like “a particularly dense student.” Mao then proposed that the discussions continue the next day at his private residence inside the Communist Party’s inner sanctum, a luxury compound known as Zonghanhai.

Mao Invites Khrushchev to Go Swimming

Mike Dash wrote in Smithsonianmag.com: “Mao had plainly done his homework. He knew how poorly educated Khrushchev was, and he also knew a good deal about his habits and his weaknesses. Above all, he had discovered that the portly Russian — who weighed over 200 pounds and when disrobed displayed a stomach resembling a beach ball — had never learned to swim. [Source: Mike Dash, Smithsonianmag.com, May 4, 2012

“Mao, in contrast, loved swimming, something that his party made repeated use of in its propaganda. He wasn’t stylish (he mostly used a choppy sidestroke), but he completed several long-distance swims in the heavily polluted Yangtze River during which it was claimed that (with the aid of a swift current) he had covered distances of more than of 10 miles at record speed. So when Mao turned up at the talks of August 3 dressed in a bathrobe and slippers, Khrushchev immediately suspected trouble, and his fears were realized when an aide produced an outsize pair of green bathing trunks and Mao insisted that his guest join him in his outdoor pool.

“A private swimming pool was an unimaginable luxury in the China of the 1950s, but Mao made good use of his on this occasion, swimming up and down while continuing the conversation in rapid Chinese. Soviet and Chinese interpreters jogged along at poolside, struggling to make out what the chairman was saying in between splashes and gasps for air. Khrushchev, meanwhile, stood uncomfortably in the children’s end of the pool until Mao, with more than a touch of malice, suggested that he join him in the deeper water.

“A flotation device was suddenly produced — Lorenz Luthi describes it as a “life belt,” while Henry Kissinger prefers “water wings.” Either way, the result was scarcely dignified. Mao, says Luthi, covered his head with “a handkerchief with knots at all the corners” and swept up and down the pool while Khrushchev struggled to stay afloat. After considerable exertion, the Soviet leader was able to get moving, “paddling like a dog” in a desperate attempt to keep up. “It was an unforgettable picture,” said his aide Oleg Troyanovskii, “the appearance of two well-fed leaders in swimming trunks, discussing questions of great policy under splashes of water.”

“Mao, Taubman relates, “watched Khrushchev’s clumsy efforts with obvious relish and then dived in the deep end and swam back and forth using several different strokes.” The chairman’s personal physician, Li Zhisui, believed that he was playing the role of emperor, “treating Khrushchev like a barbarian come to pay tribute.”

Fallout of the Khrushchev- Mao Swimming Episode

Mike Dash wrote in Smithsonianmag.com: “Khrushchev played the scene down in his memoirs, acknowledging that “of course we could not compete with him when it came to long distance swimming” and insisting that “most of the time we lay around like seals on warm sand or a rug and talked.” But he revealed his true feelings a few years later in a speech to an audience of artists and writers: He’s a prizewinning swimmer, and I’m a miner. Between us, I basically flop around when I swim; I’m not very good at it. But he swims around, showing off, all the while expounding his political views…. It was Mao’s way of putting himself in an advantageous position.

The results of the talks were felt almost immediately. Khrushchev ordered the removal of the USSR’s advisers, overruling aghast colleagues who suggested that they at least be allowed to see out their contracts. In retaliation, on Khrushchev’s next visit to Beijing, in 1959, Taubman relates, there was “no honor guard, no Chinese speeches, not even a microphone for the speech that Khrushchev insisted on giving, complete with accolades for Eisenhower that were sure to rile Mao.” In turn, a Chinese marshal named Chen Yi provoked the Soviets to a fury, prompting Khrushchev to yell: “Don’t you dare spit on us from your marshal’s height. You don’t have enough spit.” By 1966 the two sides were fighting a barely contained border war.

“The Sino-Soviet split was real, and with it came opportunity for the U.S. Kissinger’s ping-pong diplomacy raised the specter of Chinese-American cooperation and pressured the Soviets into cutting back aid to the North Vietnamese at a time when America was desperate to disengage from its war in Southeast Asia. Disengagement, in turn, led quickly to the SALT disarmament talks — and set in motion the long sequence of events that would result in the collapse of the Soviet bloc in 1989.

Traveling, Security and Mao

Mao usually traveled in an 11-car train that was described as a traveling palace. He and his wife Jiang Qing each had separate cars. "Mao's quarters were outfitted with one of his huge wooden beds and a large supply of books," his doctor Dr. Li Zhisui wrote. "All traffic along the entire rail line was stopped for the duration of Mao's journeys, and rail traffic throughout the country often became so snarled that schedules would not return to normal for a week." [Source: "The Private Life of Chairman Mao" by Dr. Li Zhisui, excerpts reprinted U.S. News and World Report, October 10, 1994]

"Mao's vast insulating security system was copied from the Soviets and his whereabouts's was always kept secret from all but the highest party leaders. His food was tasted for poison; and his private quarters were bugged without his knowledge. Whenever he went for a walk he never took the same route twice and the license plate on his car was constantly changed. The platforms of train stations were cleared when his train passed through and sometimes security guards were hired to act as hawkers so the stations didn't look 'so eerily empty.'"

China produced a 10-meter-long, six-door stretch Red Flag stretch limousine after Mao said: “'We must produce our own longest limousine.” After several years the car was produced at the First Automobile Works in Jilin Province and was delivered just weeks before Mao died. Mao was the only one ever to be driven around in it. Large enough to hold 40 schoolchildren, the limousine was equipped with a refrigerator, color television, telephone, desk and a double sofa, one of which could be converted into a double bed.

See Red Flag Limo Under AUTOMOBILES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Mao's Personality Cult

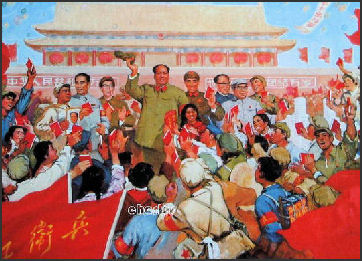

Henry Kissinger wrote, "Mao overshadowed all his subordinates by the near-religious awe in which he seemed to be held (or which his subordinates at least thought was wise to affect)." Nursery school toddlers used to walk around with the "Little Red Book" in their pockets; kindergarten children learned patriotic songs that praised Mao on their first day of school; huge concrete statues, with one armed raised in patriarchal salute to the masses, were in every town and city.

People walked around with badges with the picture of the "Great Helmsmen," as Mao was known. Mao's portrait hung in practically every shop, every house and every major public area in China. According to one government statistic there were 700 million portraits of Chairman Mao hanging on Chinese walls at the time of his death in 1976.

Orville Schell described Chinese politics from the mid 1950s until the mid 1970s as a "struggle between those who supported Mao's cult and those who feared it." Blemishing a Mao portrait is still a felony today.

Mao Suit and Little Red Book

Mao in Mao suit

The Mao suit as the standard form of Communist dress, Dr. Li said, evolved out of the chairman's distaste for protocol. In 1949 his chief of protocol told him that it was good idea to wear a dark-colored suit and black leather shoes while receiving foreign ambassadors. "Mao refused and began wearing what we then called the Sun Yat-sen suit and black leather shoes," Li wrote. "When other leaders imitated him, the name of the outfit changed. The grey “Mao suit” became the uniform of the day. The protocol chief was fired and later committed suicide during the Cultural Revolution." [Source: "The Private Life of Chairman Mao" by Dr. Li Zhisui, excerpts reprinted U.S. News and World Report, October 10, 1994]

"Mao's Selected Thoughts", a collection of sayings better known as "The Little Red Book", was put together by Lin Biao in the Cultural Revolution. According to Time magazine, "No other book has had such a profound impact on so many people at the same time...If you read it enough it was supposed to change your brain.” Some of the passages of the Little Red Book were set to music and slogans like "Reactionaries are Paper Tigers" and "We Should Support Whatever the Enemy Opposes"! were painted everywhere on billboards and walls.

Tania Branigan wrote in The Guardian, “Only the Bible has been printed more often than the Quotations, which was a keystone of Mao's personality cult. A billion copies circulated in the Cultural Revolution – the population pored over it in daily study sessions; illiterate farmers memorised chunks by heart. In the west, translations were brandished by radicals. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, September 27, 2013 ***]

“Many knew the text well enough to cite quotes by page number; they became ideological weapons to be wielded in any political struggle. Under siege by Red Guards, the then foreign minister reportedly retorted: "On page [X] it says Comrade Chen Yi is a good cadre …" But they also coloured even commonplace exchanges, as described by one historian: "Serve the people. Comrade, could I have two pounds of pork, please?" ***

“But the political frenzy ebbed, and production of the Little Red Book had mostly stopped long before Mao's death; afterwards, as China embarked on reform and opening up, officials began to pulp copies. Later, in a more relaxed age, commercial reprints and introductions to his thought appeared, but no new editions of his works: "This has been a very sensitive topic," said Daniel Leese, author of Mao Cult and an expert on the era at the University of Freiburg.” ***

Mao-Era Propaganda

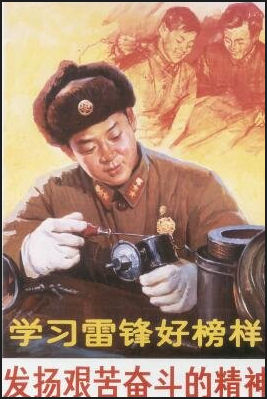

Model Worker Lei Feng

Control of the media and culture is essential for leaders to get their message and agendas across. Mao Zedong once said that control of information and control of the gun are the two pillars of Communist Party power.In the old days, Communist propaganda had a strong influence on the masses. A single word or phrase from Mao Zedong could mobilize millions. These days propaganda is largely greeted with a shrug. Few people tale it seriously anymore. Even so political satire in China is largely absent. China doesn’t even allow cartoons of its leaders.

"Serve the People" is probably the most famous slogan of the Chinese Communist Party. "Enemy of the People" was widely used in the Mao era. The use of the word "the enemy" comes from Mao's famous 1957 speech, "On the Correct Handling of Contradictions Among the People", which instructed officials, when dealing with alleged offenders, to distinguish between two types of social contradictions: those "between the enemy and us" and those "among the people". The former were to be handled with the unremitting severity of dictatorship.

The Communists viewed literature and culture primarily as a propaganda devices. In a piece entitled Yan'an Talks of Art and Literature, Mao argued that literature was something that should be used for a revolutionary purposes. Most Communist literature is about peasants who overcome great odds to achieve great things. One U.S. diplomat told the Wall Street Journal, "When things look too good to be true here, they usually are." Dahzai model commune, which was shown off to foreign visitors, for example, was a big hoax. It declined after Mao's death and the end of subsidies. See Dahzai Commune, Agriculture, Economics

See Separate Article MAO-ERA PROPAGANDA: MODEL CITIZENS, EVIL LANDLORDS AND THE LITTLE RED BOOK factsanddetails.com

Mao’s Personality Cult as Reflected People’s Daily Articles

William Wan wrote in the Washington Post, In 2014 study, “Qian Gang — a former journalist who is director of the China Media Project at the University of Hong Kong — and student researchers examined the People’s Daily, the party’s flagship paper. They compared its coverage of eight top party leaders: Mao Zedong, Hua Guofeng, Deng Xiaoping, Hu Yaobang, Zhao Ziyang, Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao and Xi Jinping. They focused on the first 18 months after each leader had taken power, counting the number of articles, front-page appearances and articles mentioning them in the paper’s first eight pages. [Source: William Wan, Washington Post, July 25, 2014 +++]

“Among past leaders, Mao and Hua were mentioned most frequently, unsurprising given the fervent state-leader worship during their time. The cult of Mao, for example, reached its peak in the late 1960s, during which he was called China’s bright red sun and the great savior of the country’s people. During the Cultural Revolution, he was branded “the great leader, the great supreme commander, the great teacher and the great helmsman.” His words were deemed infallible. Badges, busts and posters bearing his image were ubiquitous. Almost everyone carried a little red book that contained his famous quotes. +++

“But when the chaos of the Cultural Revolution abated and Deng rose to power as the next leader, he criticized the cult of personality and said it was not only unhealthy, but also dangerous to build a country’s fate on the reputation of one man. In 1980, the party’s Central Committee issued directives for “less propaganda on individuals.” Party leaders have since continued to feature in propaganda and party-controlled newspapers but with less frequency and intensity.” +++

Image Sources: Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/ and Noll websites http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html ; YouTube

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2021