JIANG QING

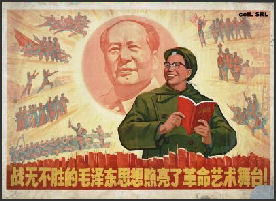

Jiang Qing poster Mao's forth wife, Jiang Qing, was a major force behind the Cultural Revolution and a member of the Gang of Four. She is remembered as a power-hungry, narcissistic, and vengeful old women who was driven to extremism by the humiliation of Mao's endless womanizing.

Jiang is sometimes referred to as Madame Mao and has been variously described as the White-Boned Demon, and a Marxist-Leninist Eva Peron. Jiang once declared ‘sex is engaging in the first rounds, but what really sustains attention in the long run is power.” Anchee Min, author the novel “Becoming Madame Mao” told the New York Times, "She's the concubine who gets too much power and destroys the dynasty. It's a very old story in China."

Qing was born in 1914 to the concubine of a small-town landowner. She joined a theatrical troupe at 14 and starred in several stage productions and movies produced in Shanghai. Qing was regarded as a second — rate actress when she met up with Mao in Yennan in 1937 after the Long March while he was still married to his third wife..

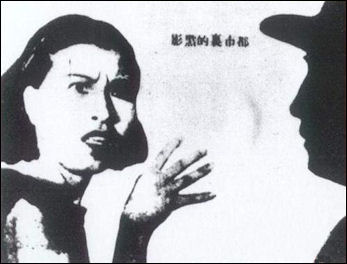

Jiang Qing movie shot, 1934 Good Websites and Sources: Jiang Qing Wikipedia article Wikipedia Lin Biao Marxist.org marxists.org ; CNN cnn.com/SPECIALS ; Zhou Enlai Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Communist Party History Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Illustrated History of Communist Party china.org.cn ; Everyday Life in Maoist China.org everydaylifeinmaoistchina.org; Mao Zedong Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Mao Internet Library marx2mao.com ; Paul Noll Mao site paulnoll.com/China/Mao ; Mao Quotations art-bin.com; Marxist.org marxists.org ; New York Times topics.nytimes.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

Madame Mao “ by Ross Terrill (Stanford) Amazon.com;

“Becoming Madame Mao”, a novel by Anchee Min. Amazon.com;

“The Culture of Power: The Lin Biao Incident in the Cultural Revolution”

by Qiu Jin Amazon.com;

“Liu Shaoqi and the Chinese Cultural Revolution” by Lowell Dittmer Amazon.com;

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: REPRESSION UNDER MAO, THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION AND NIXON factsanddetails.com; REPUBLICAN CHINA, MAO AND THE EARLY COMMUNIST PERIOD factsanddetails.com; MAO'S PERSONALITY CULT, LEADERSHIP AND MAOIST PROPAGANDA factsanddetails.com MAO'S PRIVATE LIFE AND SEXUAL ACTIVITY factsanddetails.com; COMMUNISTS TAKE OVER CHINA factsanddetails.com; FAMOUS ESSAYS BY MAO ZEDONG AND OTHER CHINESE COMMUNISTS AS THEY TAKE POWER factsanddetails.com; EARLY COMMUNIST CHINA UNDER MAO factsanddetails.com; DEATH AND REPRESSION UNDER MAO factsanddetails.com; HUNDRED FLOWERS CAMPAIGN AND THE ANTI-RIGHTIST MOVEMENT factsanddetails.com; GREAT LEAP FORWARD: MOBILIZING THE MASSES, BACKYARD FURNACES AND SUFFERING factsanddetails.com

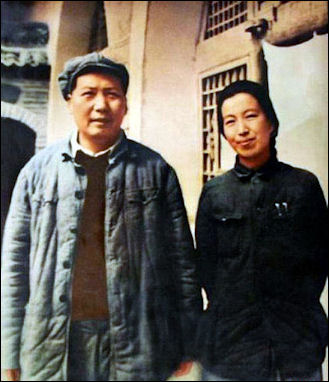

Jiang Qing and Mao

Mao and Jiang in 1946 Mao and Jiang Qing married in 1928. They had a daughter, Li Na. Despite the fact that she discovered her husband in bed on several occasions with other women Jiang was one of Mao's most loyal supporters. She once said she "was Mao's dog — whoever he told me to bite I bite." Jiang also claimed that most of Mao's post World War II writings were actually hers.

There was 20-year gap between Mao and his wife, Li wrote, "and their tastes and preferences were completely different. Mao read voraciously, Jiang was to impatient to read. Mao prided himself on his health and physical prowess. Jiang wallowed in her illness. Mao relished hot and spicy Hunan dishes. Jiang liked bland fish and vegetables and fancied herself a connoisseur of the Western food that Mao despised." One of Jiang's favorite pastime was watching Hollywood movies. She was particularly fond of “Gone With the Wind”. [Source: "The Private Life of Chairman Mao" by Dr. Li Zhisui, excerpts reprinted U.S. News and World Report, October 10, 1994]

Jiang Qing reportedly downed tranquilizers to calm her fear of noise. Once she got so high she fell off a toilet and broke her collarbone. Convinced at she was poisoned by Lin Biao she ordered her doctors to be interrogated in front of the ruling Politburo.

Jiang spent 13 years in prison after the Gang of Four Trial at the end of the Cultural Revolution in the late 1970s. She committed suicide by hanging herself in her cell in May, 1991. Jiang’s operas have been banned since the 1970s. She was a major figure in the opera “Nixon in China” (1987) by John Adams and became the subject of her own opera “Madame Mao” by Bright Sheng.

Jiang Qing, Mao, the Gang of Four and the Cultural Revolution

Jiang Qing was a member of the Gang of Four and some say she was one of the masterminds of the Cultural Revolution. According to some scholars the whole ordeal grew out of an attempt to extrapolate her radical ideas about the arts to society as a whole and became an experiment that went out of control.

Others disagree and say Mao was the mastermind. One bodyguard said: “Jiang Qing could only make suggestions not decisions.” Some believe that she made a kind of deal with Mao in that she would look the other towards his philandering’she once caught him in bed with one of her nurses and for a while was only allowed to speak to him through his mistress if he gave her radical leftist political ideas support.

Mao is now widely regarded not only as the inspiration for the Cultural revolution but was also the instigator of it and micro-manager of many of its events. Mao felt that revolutionary spirit had disappeared and the government had become ruled by a new class of mandarins — engineers, scientists, scholars and factory managers — and these people were a threat to his power and something had to be done to undermine them.

The Cultural Revolution was blamed almost entirely on the Gang of Four, a group of Communist leaders, with their power base in Shanghai, made up of Mao's wife Jiang Qing and her three allies — Yao Wenyuan, Zhang Chunqiao and Wang Hongwen. When the Chinese refer to the Gang of Four today they sometimes hold up five fingers — the fifth being a reference to Mao himself.

The Gang of Four directed the purge against moderate party officials and intellectuals during the Cultural Revolution. Jiang was leader. Yao, dubbed killer with a pen, was the group’s propagandist. On Jiang’s order Yao wrote the review condemning the popular Beijing play that triggered the Cultural Revolution. A diary entry revealed during his trial read: “Why can’t we shoot a few counterrevolutionary elements? Afer all, dictatorship is not like embroidering flowers.”

See Separate Articles: CULTURAL REVOLUTION: CAUSES, COSTS, BACKGROUND HISTORY AND FORCES BEHIND IT factsanddetails.com ; TRIAL OF THE GANG OF FOUR AND THE WINDING DOWN AND END OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com

Revolutionary Opera and Jiang Qing

Revolutionary Opera created by Communists in the Cultural Revolution gloried farmers, workers and soldiers rather heros from the feudal aristocracy. The plots revolved around class struggle and revolution and had titles like such as Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy.

The popular play that many scholars say triggered the entire Cultural Revolution was The Dismissal of Hai Rui from Office, a drama by historian Wu Han about an obscure Song dynasty official. The play was widely seen as as a traitorous critique of Mao's dismissal of Peng Dehuai, a military leader who criticized the Great Leap Forward.

Mao’s wife Jiang Qing was put in charge of the arts during the Cultural Revolution. She and her group of loyalist intellectuals and artists controlled everything: film studios, operas, theatrical companies and radio stations. Jiang reviewed more than 1,000 operas and concluded that nearly all of them were unacceptable because they dealt with "emperors, officials, scholars and concubines." She commissioned a series of "revolutionary modern model operas” with heroic figured that displayed socialist virtues. These operas were based on Peking opera but featured Western devises that were deemed appropriate for furthering revolutionary goals.

Jiang Qing decided that eight operas were the only permitted forms of art in China, and they are heavily associated with the ideologically-charged violence of the period. Among the eight operas authorized by Jiang were The Girl with White Hair (about a woman who loses her natural coloring because of an evil landowner), Red Women's Detachment, and Songs of the Long March. The operas were adapted for symphony orchestras, dance troupes, piano music and even ethnic minority songs. In the 1960s, Chinese teenagers listened to songs form these operas while Americans were listening to the Beatles and the Supremes. Alex Ross wrote in The New Yorker, Red Detachment of Women has “a kitschily charming score in a light-classical vein, with an array of native-Chinese sounds.”

See Separate Article: REVOLUTIONARY OPERA AND MAOIST AND COMMINIST THEATER IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Jiang Qing's Grave and $64,000 Photograph

Jiang Qing when she

was a Shanghai actress In November 2013, a photograph of Jiang Qing was sold at an auction for $64,000. The

Wall Street Journal reported: “Taken more than half a century ago, a photograph by Jiang Qing sold at a Beijing auction on Saturday for 391,000 yuan (more than $64,180), almost 20 times its 20,000 yuan estimate. The photograph, titled “Lushan Fairy Cave,” was captured in 1961 and the black-and-white print depicts the mountain in the distance with branches of the tree appearing in the foreground. A temple is visible at the top of the mountain, which is surrounded by a clouds and contrasting light. Lushan held a special significance for Mao. Located in Jiangxi province along the Yangtze River, the town was one of his favorite summer vacation spots. After ousting the nationalist Kuomintang party from power in 1949, Mao took over a villa that had been occupied by his rival Chiang Kai-shek. [Source: Wall Street Journal, China Real Time Blog, November 18, 2013 ^^]

“Lushan was the site of a major meeting for the Communist party leaders in 1959, during which Mao wrote the poem “Ascent of Lushan . Two years later, party leaders congregated there again for a meeting, when Jiang — sometimes known as Madame Mao — took her photograph. According to the firm that sold the lot, Huachen Auctions, Jiang learned photography from Shi Shaohua, a vice president of the Xinhua News Agency. Her photograph of Lushan impressed Mao so much that he penned a poem for her, nowadays often taught and read by Chinese students, which praises the dramatic landscape. The sale of the photo comes at a time when Mao is surging in popularity and increasingly referred to in political chatter. Chinese President Xi Jinping this year visited the Lushan villa that inspired the poems and photo, saying that the building should become a center for educating youth about patriotism and revolution. Huachen said both the buyer and seller were private collectors, and declined to give further information.” ^^

In 2021, Radio Free Asia reported that Communist authorities were allowing public access to the grave of Jiang Qing at Beijing Futian Cemetery. One Beijing resident said that situation was in contrast with the state security police detail that guarded the grave of late ousted premier Zhao Ziyang, who fell from power after Tiananmen Square crackdown. “People aren’t allowed to pay their respects at Zhao Ziyang’s grave, and yet Jiang Qing’s grave is open to the public,” she wrote. “The CCP is afraid of whom the public might admire most.” Jiangsu-based rights activist Zhang Jianping said most of the visitors were “leftists,” supporters of a command economy, collective ownership and cradle-to-grave state support for individuals. “There were a lot of leftists at the grave of Li Yunhe this Qing Ming,” Zhang said, using the birth name of Jiang Qing. “This is indicative of a divided society, not an open and pluralistic one.” [Source: Qiao Long, Radio Free Asia, April 7, 2021]

Lin Biao

Lin Biao and Mao

Lin Biao was a founding father of the People’s Republic later condemned as a counter-revolutionary. Sometimes referred to as the evil genius of China or the Chinese Trotsky, he accompanied Mao on the Long March and came up with idea of the Little Red Book and chose the quotations. As the minister of defense and head of the People's Liberation Army, he served Mao well as a brilliant military tactician, a suburb propagandist and skilled organizer of the masses. For many years he stood in the wings as Mao's handpicked successor.

In April 1969, the Communist Party elevated Lin Biao as Mao's heir-apparent and "closest comrade in arms." The same year, a 15-year-old Xi Jinping, China's current leader, was sent to work in a tiny village in his father's home province of Shaanxi.[Source: Associated Press, June 2, 2016 \^/]

Tristan Shaw wrote in Listverse: “During the 1960s, the great general Lin Biao was one of Mao Tse-tung’s most trusted men. He was vice chairman of the Communist Party and Mao’s designated successor. While Lin survived the early purges of the Cultural Revolution unscathed, Mao became increasingly worried about his influence in the party. By 1971, Lin and his supporters had fallen out of favor with the Maoists, and Lin found himself isolated from the party leadership. [Source: Tristan Shaw, Listverse, June 24, 2016 -]

Lin Biao Neurotic Personality

Lin Biao was a twisted and neurotic man addicted to morphine and opium. He was terrified of the sun, light, water and wind. He rarely went outside and spent much of his time in a bomb shelter or a house with no windows. When Biao stayed in a hotel he insisted that curtains be pulled. In the 1940s he was sent to the Soviet Union for treatment for his morphine and opium addiction.

Mao and Lin Biao poster

Lin’s fear of water was so extreme that even the sound of it gave him instant diarrhea. He never used a toilet — preferring a bedpan instead — and he didn't drink liquids (his wife dipped steamed buns in water and fed them to him). When he defecated he placed the pan on top of his bed and squatted over it with towel placed over his head.

"What struck me most when I first met Lin Biao," wrote Li, "was his army uniform. It was so tight it might have been glued on...I was [once] asked to visit him at his home. Lin was in bed, curled in the arms of his wife, Ye Qun, his head nestled against her bosom. He was crying, and Ye Qun was with him patting him and comforting him like a baby. [Source: "The Private Life of Chairman Mao" by Dr. Li Zhisui, excerpts reprinted U.S. News and World Report, October 10, 1994]

Lin Biao and the Plan to Oust Mao in a Coup

There was an internal power struggle between Mao and Lin Biao during the Cultural Revolution because Lin’s power in the army as well as in the Party leadership had apparently become too strong in Mao’s view. In September 1971, Lin Biao reportedly hatched a plan to assassinate Mao and take over the Chinese government. Apparently he had grown tired of waiting for Mao to die and had become disillusioned with Mao's policies. When the plot was discovered Mao was ordered to go to the Great Hall of the People because it was easiest palace to protect him and Lin Biao hopped on a plane to flee the country.

Tristan Shaw wrote in Listverse: In 1971, “the Chinese government had uncovered a conspiracy by Lin Biao to launch a coup. The plot, code-named Project 571, also intended to assassinate Mao Tse-tung. According to the party’s account, the Lins attempted to escape China after the coup failed. [Source: Tristan Shaw, Listverse, June 24, 2016 -]

“Despite what the Communist Party maintains, there is still a great deal of controversy over Project 571. Critics believe that it was Lin Liguo, not his father, who was probably the head of the conspiracy. In fact, Lin Biao might have been entirely innocent. The cause of the plane crash has also been disputed. Some skeptics have suggested that the plane was sabotaged or shot down. Strangely, the plane’s pilot Pan Jingyin was posthumously given the honorary title of “Revolutionary Martyr.” -

Lin Biao’s Plane Crash and Its Aftermath

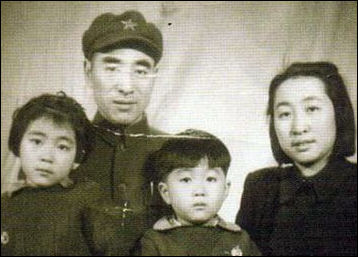

Lin and his family On September 13, 1971, Lin, then defense ministe. died in a plane crash in Mongolia along with close family members and aides while apparently fleeing China. It was alleged that he was fleeing to the Soviet Union after an abortive attempt to assassinate Mao and establish a military dictatorship. Mao was left without a successor while his wife Jiang Qing exerted ever greater influence on culture and politics as leader of the "Gang of Four."

Tristan Shaw wrote in Listverse: “On September 13, 1971, Lin, his wife, and his son Liguo boarded a plane and tried to flee to the Soviet Union. The plane’s fuel was low, and the Lins were in such a hurry that they didn’t bother to bring a copilot or navigator with them. As government officials followed the plane on radar, it passed over Mongolia and then crashed. There were no survivors, and while the nine corpses that were aboard were scorched, autopsies conducted by the Soviet Union were later able to identify the remains of the Lins. [Source: Tristan Shaw, Listverse, June 24, 2016 -]

"We soon learned that the plane had taken off in such haste," Mao's doctor, Dr. Li Zhisui wrote, "that it had not been properly fueled. Carrying at most a ton of gasoline, the plane could not go far. Moreover it had struck a fuel truck on taking off, and the right landing gear had fallen off...The next afternoon, a message came from the Chinese ambassador in Ulaan Baatar. A Chinese aircraft with nine people on board — one woman and eight men — had crashed in the Under Khan area of Outer Mongolia. Everyone on board hade been killed. Three days later...dental records had positively identified Lin Biao as one of the dead." [Source: "The Private Life of Chairman Mao" by Dr. Li Zhisui, excerpts reprinted U.S. News and World Report, October 10, 1994]

The Lin Biao incident was a heavy blow to Mao. All of Lin’s associates in the military and the Party were subsequently arrested. After the plane crashed Mao became depressed and stayed in bed for weeks. He became so weak and breathing was so difficult he could not even cough. Lin Biao has been airbrushed out of photographs at the Mao Museum.

The immediate consequence was a steady erosion of the fundamentalist influence of the left-wing radicals. Lin Biao's closest supporters were purged systematically. Efforts to depoliticize and promote professionalism were intensified within the PLA. These were also accompanied by the rehabilitation of those persons who had been persecuted or fallen into disgrace in 1966-68. [Source: Library of Congress]

Lin Biao’s Daughter Calls for Historical Truth

In November 2014, Zhuang Pinghu wrote in the South China Morning Post, “The daughter of Lin Biao called for “more respect for historical facts” as she joined about 100 “second-generation reds” to mark a major military congress and battle. Lin Doudou made the call as the children of revolutionary figures gathered to mark the 85th anniversary of the Gutian Congress in Fujian province. It was in Gutian in 1929 that late leader Mao Zedong established the principle that the “party leads the army”. [Source: Zhuang Pinghu, South China Morning Post, November 7, 2014 ^*^]

“Many of those at the Beijing gathering came from military families, including Luo Dongjin, son of PLA founding general Luo Ronghuan, and Su Rongsheng, son of veteran commander Su Yu, according to an article carried by Xinhua. They also met to commemorate a brutal battle in Zhangzhou, Fujian, two years after Mao’s Gutian Congress, and issued an open letter to party leaders, urging them to set up a state-level martyrs commemoration centre and to complete construction of a Zhangzhou martyrs park by April 2016. ^*^

“Amid rumours of the possibility of a more open-minded approach to reports on Lin Biao, Lin Doudou urged greater speed in “collecting facts on historic events”. Independent historian Zhang Lifan said these kinds of commemorations were a way for participants to have a bigger say.“The second-generation reds feel they finally have ‘one of them’ in charge and they want their appeals heard, including for official recognition for what their fathers did,” Zhang said. “They want to commemorate what their fathers did for the founding of this county and … have more of their voices heard.” He also said that Xi would be keen to have more support from “second-generation reds” and the military, which he needs to consolidate power. “All in all, both Xi and the [second-generation] reds need each other.” ^*^

Zhou Enlai

Liu Shaoqi and Zhou Enlai in 1939

Zhou Enlai has been portrayed for decades as being the good Communist, who tried to stop the excesses of Maoism and was credited with opening China up to the West. Zhou wrote little, lacked charisma and was no theorist but the Chinese liked and trusted him because he was "polite, urbane and kind," "honest," and a good man" who "worked hard from the Chinese people." Henry Kissinger once said that Premier Zhou Enlai was the among the most impressive men he ever met. While Zhou charmed Kissinger and others, he could be both am erudite, smooth-talking negotiator and conniving plotter. It should also be remembered that he first made an impact in the late 1920s as the head of a communist hit squad.

Zhou Enlai got his start as a labor organiser. After the the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Zhou became premier and foreign minister. He headed the Chinese Communist delegation to the Geneva Conference of 1954. In 1958, he relinquished the foreign ministry but retained the premiership. Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner wrote in “CultureShock! China”: A practical-minded administrator, Zhou maintained his position through all of Communist China’s ideological upheavals, including the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. Although supportive of government initiatives, Zhou was reputed to be a voice of reason behind the scenes and helped restrain extremists. As a result, he was attacked by Red Guards for attempting to shelter its victims. He is credited with arranging the historic meeting between US President Nixon and Chairman Mao. Zhou initiated contact with the West that eventually led to the US recognition of the communist government in China. [Source: “CultureShock! China: A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette” by Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner, Marshall Cavendish 2011]

Zhou was often portrayed as a good cop to Mao’s bad cop. When Mao argued that the inspiration of the masses was enough to pull off the Great Leap Forward, Zhou supported an incentive program. During the Cultural Revolution. Zhou was praised for restraining Mao and saving the Forbidden City from the Red Guards. Zhou was never criticized in public, but he often fell out of favor with the party and with Mao. Many were surprised that he survived the Cultural Revolution. Asked for his views on the French Revolution, Zhou Enlai famously replied that it was too early to say.

When the worst of the Cultural Revolution was over in 1969, Zhou set about redirecting the Chinese government and opening up China to the outside world. He ran the day-to-day affairs of China when Mao's health began to decline. He invited the American ping pong team to China in 1971, and was the one who met Nixon when he arrived in Beijing airport in 1972. He also help rehabilitate Deng Xiaoping.

“Zhou Enlai’s Later Years”, a book by Chinese Communist Party historian Gao Wenqian, challenged the depiction of Zhou as a great hero. The book, published in December 2003 and based on documents from Communist Party’s central Documents Office, portrays him as a backroom schemer and a puppet of Mao who was so devoted to the Chinese leader he signed the arrest warrants for his own brother and goddaughter. Rather than being a critic of the Cultural Revolution, the book asserts, Zhou was an enthusiastic participant who was responsible for sending hundreds of thousands to labor camps.

Zhou Enlai’s Life and Death

Zhou Enlai was born into a prominent family in 1898 in the town of Huai'an in Jiangsu Province, and many people believe that he was the real hero of the Communist Revolution not Mao. He studied in Japan from 1917 to 1919 and was one of the founding members of the Communist Party, a participant in the Long March, and was the premier of China from 1949 until his death in 1976. After the Communist takeover in 1949 he maintained a decades-log secret communications with Chiang Kai-Shek.

Mao’s doctor Dr. Li Zhisui was also critical of Zhou. He described Zhou as a "servile opportunist whose main object was survival...More than any other of China's top leaders, he had remained loyal to Mao’so faithful, in fact that Lin Biao had once characterized him as 'an obedient servant.” I was present on Nov. 10, 1966, when he and Mao met to plan the seventh gathering of Red Guards in Tiananmen Square...As Zhou explained his plan to Mao, he spread a map on the floor, kneeling to show Mao the direction his motorcade would take. Mao stood, smoking a cigarette and seemed to take sardonic pleasure in watching Zhou crawl.” [Source: "The Private Life of Chairman Mao" by Dr. Li Zhisui, excerpts reprinted U.S. News and World Report, October 10, 1994]

Zhou En Lai and Nixon

In 1972 when Zhou was diagnosed as having bladder cancer, Mao denied him medical treatment and didn’t let doctors tell him he had the disease on the grounds that "cancer can not be cured and treatment only caused pain and mental anguish." Mao is believed to have done this to keep Zhou from outliving Mao and becoming leader of China. In 1974, Zhou was for all practical purposes retired from political life. He died in January 1976. Mao was reportedly so happy when he heard the news that Zhou had died he lit firecrackers.

After Zhou's death, thousands showed up to mourn him at Tiananmen Square during the Qingmang Festival, a traditional holiday that honors the dead. In an incident that resembled the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989, the outpouring of grief grew into protest against the Gang of Four, and Mao ordered police to disperse the crowd. Hundreds were hurt and arrested and leaders were denounced for mounting a "counterrevolutionary insurrection." Mao died six months later. Although Zhou was regarded with great respect after the death of Mao he has now he had largely been forgotten.

Liu Shaoqi — the Party Leader Who Challenged Mao and Paid for It

Liu Shaoqi (1898-1969) was an elite Communist Party member once declared as Mao Zedong’s successor but who later had a falling out with Mao and eventually died in prison during the Cultural Revolution. Liu accompanied Mao on the Long March. For 15 years, in the 1950s and 60s, he was the second most powerful man in China, behind only Chairman Mao, serving as Chairman of the NPC Standing Committee, the most powerful political body in China, from 1954 to 1959, First Vice Chairman of the Communist Party of China from 1956 to 1966 and Chairman of the People's Republic of China, the head of state, from 1959 to 1968.

Liu was born into a moderately rich peasant family in 1898 in Huaminglou village, Ningxiang, Hunan province. Mao was also from Hunan. While in secondary school he was recommended to attend a class in Shanghai to prepare for studying in Russia. In 1920, he joined a Socialist Youth Corps. In 1921, Liu studied at the Comintern's University of the Toilers of the East in Moscow. He was married was five times. His third wife, Xie Fei, was one of the few women on the 1934 Long March. [Source: Wikipedia]

Liu met Mao, just as he was becoming a communist, in Changsa, Hunan when Mao was the editor of a radical student newspaper called the Xiang River Review. In 1920 Mao began organizing workers and calling himself a Marxist. He recruited new members for the Communist Party with an ad in the local Changsa newspaper "inviting young men interested in patriotic work to make contact with me." This is how Mao and Liu met.

Liu Shaoqi’s Political Career

Liu Shaoqi

Liu joined the newly formed Communist Party of China (CPC) in 1921. The next year, after he returned to China from Russia, he served as secretary of the All-China Labor Syndicate and led several railway workers' strikes, in the Yangtze Valley and at Anyuan on the Jiangxi-Hunan border. In 1925, Liu became a member of the Guangzhou-based All-China Federation of Labor Executive Committee. During the following years he led numerous political campaigns and strikes in Hubei and Shanghai. In 1927 he was elected to the Party's Central Committee and appointed to the head of its Labor Department. [Source: Wikipedia]

Liu became the Party Secretary of Fujian Province in 1932. He accompanied the Long March in 1934 at least as far as the crucial Zunyi Conference, but was then sent to the so-called "White Areas" (areas controlled by the Kuomintang) to reorganize underground activities in northern China, centered around Beijing and Tianjin. He became Party Secretary in North China in 1936, leading the anti-Japanese movements in that area.. Some Japanese sources have alleged that the activities of his organization sparked the Marco Polo Bridge Incident in July 1937, which gave Japan the excuse to launch the Second Sino-Japanese War.

In 1937, Liu traveled to the Communist base at Yanan; in 1941, he became a political commissar of the New Fourth Army. He was elected as one of five CPC Secretaries at the Seventh National Party Congress in 1945. After that Congress, he became the supreme leader of all Communist forces in Manchuria and northern China. In 1949, the People’s Republic of China was declared and became an independent country, Liu became the Vice Chairman of the Central People's Government. In 1954, he was elected chairman of the Congress's Standing Committee, the highest political body in the Communist Party of China, and held this position until 1959. From 1956 until his downfall in 1966, he ranked as the First Vice Chairman of the Communist Party of China.

Liu Shaoqi and the End of the Great Leap Forward

A great famine occurred in 1959 and 1961 after Mao's inept attempts at industrialization during the Great Leap Forward, an ill-conceived plan to leapfrog Western countries through a series of poorly-thought-out economic policies. It is believed that between 30 and 45 million may have died, making it world's greatest disaster since the Great Plague of the Middle Ages, directly as result of — or at least exacerbated by — The Great Leap Forward.

Lius is credited with bringing the Great Leap Forward and Great Famine to an end but at great political cost. In the late 1950s, Liu Shaoqi, then the second-ranking member of the regime, was shocked at the conditions he found when he visited his home village. Somebody had to confront Mao over what the Great Leap Forward had unleashed and to a lare extent Liu was the person who did that. He forced the Mao and other party members to pressure Mao to retreat. [Source: The Guardian, Jonathan Fenby, September 5, 2010]

In April 1959 Mao, who bore the chief responsibility for the Great Leap Forward fiasco, stepped down from his position as chairman of the People's Republic. The National People's Congress elected Liu Shaoqi as Mao's successor, though Mao remained chairman of the CCP.

The “turning point” was the Party meeting at Lushan, Jiangxi Province in 1959, where the Great Leap Forward policy came under open criticism and Liu Shaoqi admitted that a “man-made disaster” had occurred in China. The attack was led by Minister of National Defense Peng Dehuai, who had become troubled by the potentially adverse effect Mao's policies would have on the modernization of the armed forces. Peng argued that "putting politics in command" was no substitute for economic laws and realistic economic policy; unnamed party leaders were also admonished for trying to "jump into communism in one step." After the Lushan showdown, Peng Dehuai, who allegedly had been encouraged by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev to oppose Mao, was deposed. Peng was replaced by Lin Biao, a radical and opportunist Maoist. The new defense minister initiated a systematic purge of Peng's supporters from the military. [Source: Library of Congress]

Liu Shaoqi and the Cultural Revolution

Mao launched the “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution” — the Cultural Revolution — at least in part as a way of attacking political enemies — or at least rivals — such as Liu Shaoqi (1898-1969) and Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping. On May 16, 1966, the Chinese Communist Party released a document expressing concern that bourgeoisie and counterrevolutionaries were trying to hijack the party. The May 16 Notification, as it became known, is cited by many as the spark the Cultural Revolution. The two year period between May, 1966 and the summer of 1968 was the most active and radical period of the Cultural Revolution. The period between 1968 and 1976 was a period of recovery when members of the Red Guard were re-educated and some assemblage of order was restored. Today the Cultural Revolution is officially known in China as "Ten Years of Chaos" or "Ten Years of Calamity."

The historian Frank Dikötter described how after the the Great Leap Forward humiliation Mao feared that Liu Shaoqi would discredit him just as completely as Khrushchev had damaged Stalin’s reputation. In his view this was the impetus behind the Cultural Revolution that started in 1966. “Mao was biding his time, but the patient groundwork for launching a Cultural Revolution that would tear the party and the country apart had already begun,” Dikötter wrote.

See Separate Article PROMINENT VICTIMS OF CULTURAL REVOLUTION ATTACKS factsanddetails.com

Li Rui: Story of a Mao Loyalist Turned Critic

Li Rui served (1918-2019) was one of Mao Zedong’s personal secretaries and then became a Communist Party critic, revisionist historian and standard-bearer for liberal values in China. Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Times: His work also helped reshape historians’ understanding of key moments in modern Chinese history — especially Mao’s responsibility for the catastrophic Great Leap Forward, in which famine killed more than 35 million people — while his political connections allowed him to protect moderate critics and make open appeals for free speech and constitutional government. “But Mr. Li was no dissident. He died a Communist Party member, enjoying the privileges that came from having joined the party in 1937, earlier than almost anyone else alive in China. He had a large apartment, a generous pension and lavish benefits, such as top-flight medical care. The party imprisoned him, exiled him, and almost starved him to death, but even when it expelled him he eventually returned in hopes of effecting change from within. “He saw himself as a conscience of the revolution and the party,” said Roderick MacFarquhar, a professor of Chinese history at Harvard University. “But he had grave doubts about the system he spent his life serving.” [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Times, February 15, 2019]

“Early on, Mr. Li was an enthusiastic party member. He was born in 1917 to a prosperous family in the southern Chinese province of Hunan at a time when the country was being carved up by warlords and foreign aggressors. His father was a member of the Tongmenghui, an underground revolutionary party that helped overthrow the Qing dynasty and establish a republic. He died in 1922, leaving Li Rui fatherless but eager to follow in his footsteps of political activism. While Mr. Li was a mechanical engineering student at Wuhan University, he participated in a Communist-led student movement to pressure the government to resist Japan’s recent annexation of Chinese territory. In 1937 he joined the Communist Party as an underground activist. This put Mr. Li in the vanguard of a new generation of idealistic, educated members in the Communist Party, which had been dominated by street fighters and veteran revolutionaries like Mao. Photos of him from this time show a strikingly vigorous young man with the body of an athlete and a square, jaunty face framing two piercing eyes.

Liu Shaoqi with Mao and Edgar Snow

“After the People’s Republic was founded in 1949, Mr. Li worked in the strategically important Ministry of Water Resources. In 1958 he became its deputy head, making him the youngest vice minister in China. That same year he reached the pinnacle of his career. Mao was holding a meeting in the southern city of Nanning. One item on the agenda was building the Three Gorges Dam, a massive flood-control and hydropower project on the Yangtze River that would create a vast inland lake and destroy villages and cultural relics for scores of miles upstream. Mr. Li was a known opponent, and Mao had him flown down from Beijing to debate the issue in his presence. He won Mao over by talking forcefully and simply, and was soon appointed as one of his personal secretaries — making him a powerful gatekeeper to a leader who ruled like an emperor.

“But Mr. Li’s stint at the top was short-lived. In 1958, Mao embarked on the Great Leap Forward,. Soon, farmers began starving to death.” At a critical point during the Lushan meeting in 1959 that addressed the fallout of the Great Leap Forward,” one of Mao’s personal secretaries was accused of having said that Mao could accept no criticism. The room went silent. Mr. Li was asked if he had heard the man make such a bold criticism. In an oral history of the period, Mr. Li recalled: “I stood up and answered: ‘[He] heard wrong. Those were my views.’ Mr. Li was quickly purged. He was identified, along with General Peng, as an anti-Mao co-conspirator. He was stripped of his party membership and sent to a penal colony near the Soviet border. With China besieged by famine, Mr. Li almost starved to death. He was saved when friends managed to get him transferred to another labor camp that had access to food.

“He was soon visited by government inspectors, who said he could have his party membership back if he would admit his errors. But Mr. Li was disgusted at what he had seen at the top.n“I declined because of the Lushan meeting, which involved the highest-ranking members of the party,” he recalled. “To my surprise, not one of them had had the guts to say something fair and just about General Peng. I felt despondent and hopeless. I said I agreed with being expelled from the party.”

Once his daughter wrote “an essay praising the Communist Party for preventing deaths during the Great Leap Forward. Her father upbraided her: “He said: ‘How do you know nobody died?’ His daughter said, “I stared at him and said, ‘How dare you say that? The newspapers and my teachers said nobody died, so how could you say that?’” Angry at his stubbornness, his wife of 22 years divorced him, taking their three children. She then denounced him for having made private comments against Mao. In 1962 he was banished to teach in a remote mountain region.

“Four years later, Mao launched the Cultural Revolution, which was aimed at overthrowing moderates in the party. Just as at the Lushan meeting, Mao’s own personal secretaries were under investigation for being inadequately radical. Investigators flew to Mr. Li’s mountain exile. He vouched for all of the secretaries except one, Chen Boda, who was well-known as the most leftist among Mao’s secretaries. It was a nearly suicidal act of defiance against the radical faction around Mao. A few months later, Mr. Li was sent to China’s Bastille, the notorious Qincheng prison north of Beijing, where he was held in solitary confinement for most of the next nine years. He fought the loneliness by using iodine from the prison clinic to write 400 poems in the margins of the collected works of Marx and Lenin. “This helped ease my pain and worry,” he wrote in an essay on his 99th birthday. “And helped me keep my sanity.”

In 1975, he was released from Qincheng but sent back to his mountain exile. It was only after Mao died and Deng Xiaoping took power at the end of 1978 that Mr. Li was given back party membership. He returned to Beijing to rejoin the Ministry of Water Resources. He again opposed plans to build the Three Gorges Dam, teaming up with the journalist and environmental activist Dai Qing to prevent the gargantuan project. He later was transferred to the party’s influential Organization Department, where he helped oversee the recruitment of new officials. But his career ended abruptly in 1984 when he refused to give special preference to the offspring of senior officials. He died in 2019 at the age of 101.

Image Sources: Poster images from Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/ and Nolls' websites http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html ; Wikicommons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2021